Abstract

Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) have garnered significant attention due to their cost-effectiveness and ease of fabrication; however, the performance of counter electrodes (CEs) remains a critical factor in optimizing efficiency. In this study, we investigate the synergistic role of a polyethylene oxide (PEO)/copper oxide (CuO)/graphene (G) composite (PEO/CuO/G) as a CE for DSSCs, employing both theoretical modeling and experimental validation. DFT calculations were used for investigating PEO hybridization nanocomposites with different metal oxides, including MgO, SiO2, TiO2, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2. The electronic properties analysis revealed that CuO is the most effective metal oxide in boosting the PEO polymer matrix, with a total dipole moment (TDM) of 10.482 Debye and ∆E of 0.422 eV. G is intended to strengthen the electrical characteristics of PEO/CuO by hybridizing with the optimal metal oxide. The hybrid composite of PEO/CuO/G showed significant improvement in electronic properties, with TDM of 18.7938 Debye ∆E 0.2566 eV. Interestingly, the morphological characteristics, electrical conductivity, surface roughness, and electrochemical properties of pure PEO, CuO, G, and PEO/CuO/G composites were systematically analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), surface roughness, and electrical conductivity measurements. The results demonstrated a gradual enhancement in solar cell performance, with the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite exhibiting superior electrical conductivity (12.56 S/m), high surface roughness (8.1 µm), and an interconnected conductive network, facilitating efficient charge transfer. Photovoltaic (PV) measurements revealed a systematic improvement in short-circuit current density (Jsc) from 11.428 mA/cm2 (PEO) to 16.916 mA/cm2 (PEO/CuO/G) and fill factor (FF) from 63.4 to 65.1%, leading to a notable enhancement in overall efficiency from 4.33% to 6.42%. The observed improvements are attributed to the combined effects of CuO’s catalytic properties and graphene’s high electrical conductivity, forming a stable, efficient CE material. Theoretical modeling further supports these findings by demonstrating enhanced electron transport and reduced charge recombination within the composite structure. This study highlights the potential of PEO/CuO/G as a low-cost and high-performance CE for DSSCs, paving the way for further optimization in next-generation solar energy aerospace applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing global energy demand and the depletion of fossil fuel reserves have driven extensive research into renewable and sustainable energy sources, as well as their potential applications in aerospace technologies. Among the various PV technologies, DSSCs have gained significant attention due to their low production costs, simple fabrication process, and ability to function efficiently under low-light conditions1. Despite these advantages, the performance of DSSCs is still limited by the properties of their CEs, which play a crucial role in facilitating electron transfer and enhancing the catalytic reduction of the redox electrolyte2,3.

Conventionally, platinum (Pt)-based CEs have been widely used due to their excellent catalytic activity and high electrical conductivity. However, the high cost, scarcity, and poor long-term stability of Pt electrodes have prompted researchers to explore alternative materials that can provide comparable or superior electrochemical performance4. To address these challenges, extensive efforts have been made to develop polymeric, metal oxide, and carbon-based materials as efficient CEs for DSSCs5. Among the promising alternatives, polyethylene oxide (PEO) has attracted considerable attention due to its chemical stability, flexibility, and ability to form stable composite structures with other functional materials6. However, its poor electrical conductivity and limited catalytic activity necessitate modifications through the incorporation of conductive and catalytic nanomaterials7. In this regard, copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) have demonstrated excellent redox activity, high surface area, and cost-effectiveness, making them a suitable candidate for DSSC CEs8. Additionally, graphene (G) and its derivatives have emerged as ideal materials for energy applications due to their exceptional electrical conductivity, large surface area, and superior electrocatalytic properties9,10. Recently, Jebur et al.11, developed a GQD that improved the stability and optical activity of the polymer matrix, resulting in efficient supercapacitor activity. Hashim et al.12, created PVA/PEO/CuO nanocomposites with significantly improved properties for humidity sensor applications . Moreover, computational molecular simulations were recently utilized to examine chemical interactions by analyzing molecular geometries and estimating parameters and descriptors such as molecule energies, infrared ray (IR), and structural physical properties13,14. DFT is one of various methods for exploring the physical and chemical properties of materials, and it is frequently used in organometallic interactions and nanocomposites15,16. As a result, DFT outperforms other approaches in terms of consistency with experimental data17,18. DFT calculations of a PVC/PEO/SiC nanocomposite indicated that it might be used as an optoelectronic material17. PVA-PEO-SiC also possesses good optical and electrical properties, as well as a low energy band gap, which renders it suitable for a variety of optoelectronic applications.

Notwithstanding the significant advantages of nanofillers—particularly nanometal oxides—in enhancing the physicochemical, electrical, and optical properties of polymer matrices, further research is required to fully understand their impact on structural fundamentals and the emergence of new material properties19,20. In this study, a range of metal oxides, including MgO, SiO2, TiO₂, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2, were explored for their ability to introduce functional oxygen-containing groups and promote physicochemical interactions within the PEO polymer chains21. Additionally, identifying the optimal metal oxide composition is crucial for improving the electrical and optical performance of polymer-based composites. To achieve a comprehensive understanding, both theoretical and experimental investigations were conducted. In the theoretical study, molecular modeling was employed to examine the impact of metal oxide incorporation on the electrical and optical properties of the composite. Key electronic and structural parameters such as total dipole moment (TDM), band gap energy, and molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) were computed to assess the suitability of the nanocomposites for PV applications. Additionally, the influence of graphene (G) loading on the PEO/metal oxide nanocomposite was investigated using the same computational variables22. Further analysis was carried out on total and partial density of states (TDOS, PDOS), along with key reactivity and stability descriptors, including hardness, softness, and electrophilicity. In the experimental phase, the PEO/CuO/G composite was synthesized and systematically analyzed to evaluate the effects of CuO and graphene incorporation on the structural, physicochemical, and optoelectronic properties of the PEO polymer matrix for solar cell applications. The prepared materials—PEO, PEO/MO, and PEO/MO/G—were subjected to UV–vis spectroscopy to examine their optical enhancements and light absorption characteristics.

In this study, we propose PEO/CuO/G as an efficient and cost-effective CE alternative for DSSCs. The integration of CuO and graphene within the PEO matrix is expected to significantly enhance electron transport, electrocatalytic activity, and charge separation efficiency, leading to superior PV performance. The synergistic interaction between CuO and graphene is designed to overcome the limitations associated with their individual components, ultimately improving the efficiency and stability of DSSCs. To validate the potential of this novel CE, a comprehensive analysis was conducted, covering morphological, electrical, and PV properties of pure PEO, CuO, graphene, and the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite. The findings of this study aim to contribute to the development of high-performance, low-cost DSSCs, paving the way for future advancements in solar energy conversion technologies and supporting the transition toward sustainable and scalable PV solutions.

Theoretical study

Calculation details

The simulations were performed at the Molecular Spectroscopy and Modeling Laboratory, Centre of Excellence for Advanced Science, National Research Centre, Egypt, using the GAUSSIAN09 program23. The influence of MOs such as MgO, SiO2, TiO2, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2 on the PEO polymer matrix was calculated using the B3LYP/6–31(d, p) model24,25,26. In general, the selection of a basis set depends on the nature of the structure being studied. The 6-31G(d, p) basis set is widely employed for investigating polymer interactions with nanomaterials, particularly metal oxides and carbon-based nanomaterials, as it has demonstrated strong consistency with experimental results27,28,29. While the accuracy of computational methods, functionals, and basis sets generally improves with more sophisticated configurations, an excessively large basis set does not always guarantee reliability due to the risk of overcalculation. Therefore, understanding the structural characteristics of the system is crucial before selecting an appropriate basis set. The 6-31G function, also referred to as a split-valence double-zeta basis set, describes both core and valence orbitals, incorporating "d" polarization functions for heavy atoms and "p" polarization functions for hydrogen atoms. This enhances the representation of polar bonding interactions, making it particularly useful for systems with high electron density, such as halogen ions, electronegative elements, or radical species. Given these attributes, the 6–31(d, p) basis set is well-suited for the structural and electronic properties of the studied system, ensuring a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy. In comparison to other computational models, smaller basis sets like 3-21G and STO-3G offer lower computational costs but often lack the precision required for accurately modeling complex hybrid systems, particularly polymer–nanomaterial interactions. Conversely, larger basis sets such as 6-311G + + and aug-cc-pVDZ provide a more detailed representation of electronic interactions and charge distribution, potentially improving accuracy; however, they significantly increase computational demand without necessarily offering proportionate gains in predictive capability. Additionally, alternative functionals such as M06-2X and PBE0 have shown superior performance in capturing dispersion interactions, but they are not as extensively benchmarked for polymeric and hybrid nanomaterial systems. Given these considerations, B3LYP/6–31(d, p) provides an optimal balance between computational efficiency, accuracy, and applicability, making it a well-suited choice for modeling the structural and electronic properties of the studied system.

Herein, the HOMO/LUMO orbital distribution, bandgap, and MESP mapping of model structures were investigated to see if nano MOs alter physicochemical, reactivity, stability, electrical, and optical properties. The most promising PEO/MO will next interact with G for further stability and durability enhancement, and the same calculations will be performed at the same theoretical level.

Experimental study

Methodology and techniques

Materials

All materials were utilized in the preparation without additional purification. For CuO preparation, copper sulphate pentahydrate (CuSO45H2O) was purchased from PURE, India. PEO with an average molecular weight of 4x104 g/mol was purchased from ACROS, New Jersey, USA. Glacial acetic acid and sodium hydroxide (Fisher chemical, 97%) were used as solvents. This experiment made use of distilled water (DW). Cis-bis(isothiocyanato)(2,2′-bipyridyl-4,4′-dicarboxylato)(4,4′-di-nonyl-2′-bipyridyl) ruthenium(II) (Z907, 99%) was employed as a dye.

Synthesis of CuO NPs and PEO/CuO/G Composite

The CuO NPs were synthesized using a precipitation method. Initially, CuSO4·5H₂O (1 M, 100 mL of glacial acetic acid) was heated to 70°C for 2h under continuous stirring to ensure complete dissolution. Once fully dissolved, a 2 M NaOH solution (100 mL of DW) was added dropwise under continuous stirring, leading to the formation of a black precipitate. The precipitate was then filtered and washed thoroughly with DI water to remove residual impurities. The obtained CuO was subsequently dried at 80°C for 24 h, followed by calcination at 500°C for 2h to enhance its crystallinity and purity. To prepare the PEO/CuO/G composite, 0.01 g of CuO NPs and 0.02 g of G nanosheets were dispersed in 100 mL of DI water under continuous stirring to achieve uniform dispersion. Subsequently, PEO (70 wt.%) was gradually introduced into the solution while stirring, ensuring the formation of a homogeneous mixture. The final composite solution was then left to dry at room temperature, leading to the formation of the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite.

Assembling of DSSCs

The DSSC construction method is depicted in Fig. 1, where a liquid electrolyte was positioned between a TiO2 photoanode and a PEO/CuO/G composite CE. The TiO2 photoanodes were made of highly crystalline TiO2 NPs that were created using a hydrothermal autoclave technique, as previously described in works19,22. Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass substrates (2 × 2 cm2) were thoroughly cleaned to remove organic residues before DSSC construction. The first step involved ultrasonically cleaning the substrates for five minutes in a 0.1M HCl solution in methanol. The glass surfaces were then thoroughly washed with DW and a 5 wt.% detergent solution, following a repeated rinsing in DW for several minutes. To guarantee that all impurities were eliminated, the FTO plates were then washed with ethanol and sonicated. To ensure that there were no organic contaminants, the complete cleaning process was carried out three times. After washing, the photoanode was formed by spin-coating TiO2 NPs onto the FTO substrates using a VTC-50A spin coater set to 1200 rpm for two minutes. When the Z907 dye was adsorbed onto the TiO2 surface during the dye-sensitization procedure, it was photoexcited by the light and produced electrons. The PV process was then started when these electrons were moved to TiO2's conduction band. The Z907 dye needs efficiently absorb visible light and promote charge transfer in order to transport electrons efficiently. 0.5 M lithium iodide (LiI) and 0.05 M iodine (I2) dissolved in acetonitrile or propylene carbonate were used to create a redox electrolyte solution, which served as the \({\text{I}}^{ - }\)/\({\text{I}}_{3}^{-}\) redox pair catalyst, in order to optimise this process. Furthermore, 0.6 M 1–methyl–3–propylimidazolium iodide (MPII) and 0.5 M 4–tert–butylpyridine (TBP) were added to the electrolyte in order to stabilise electrolyte viscosity, improve ionic conductivity, and increase open-circuit voltage. The PEO/CuO − G composite CE was able to successfully catalyse the reduction of \({\text{I}}_{3}^{-}\) to \({\text{I}}^{ - }\), completing the electron transport cycle in the DSSC, thanks to the efficient electron regeneration made possible by this optimised electrolyte combination. Washed FTO substrates were submerged in the PEO/CuO/G liquid at 70°C for an hour in order to create the PEO/CuO/G composite CE. A thin-film measuring system (EQ-TFMS-LD) was used to accurately regulate the deposited CE films, guaranteeing a thickness range of 200–220 nm in compliance with established standards. Ultimately, an optimised electrolyte solution, PEO/CuO/G mixture as the counter electrode (CE), and TiO2 nanofilms as the photoanode were used to create DSSCs.

Analytical techniques

All prepared samples were characterized using spectroscopic techniques such as the Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectrometer (Vertex 70, Bruker) with a spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1 and 4 cm−1 spectral resolution. Also, nanoparticles and prepared composite crystal structure were investigated by X-ray Diffraction (XRD) measurement using a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean 3 diffractometer. Finally, the pure materials and composite morphology were studied by Field-emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM, Quattro S, Thermo Scientific). A profilometer (Talysurf 50, Taylor Hobson Precision) was used to assess surface roughness in order to calculate the average roughness parameter (Ra). An EQ-JX2008-LD device was used to test electrical resistance using the four-point probe (4PP) approach. Each CPA composite’s average electrical resistance was established using more than ten data points gathered from several distinct locations. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) observations were conducted in a dark environment using an electrochemical workstation (Zahner Company, Germany) with a frequency range of 100 Hz to 100 kHz. A xenon lamp (Orial, USA) was used to replicate sunlight on devices with an active area of 0.25 cm2. Measurements were conducted under AM 1.5G (100 mW/cm2) illumination, with periodic recalibration using a certified silicon reference cell (Newport 91150V, \(\pm\) 2% error in intensity calibration) to ensure accuracy and reliability. A digital source meter with a built-in filter, the Keithley 2400, was used to capture current–voltage (I–V) characteristics. Text Point software was used to analyze the resultant data.

Results and discussion

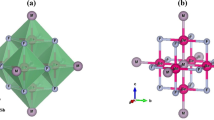

Building model molecule

Smart, sustainable, and affordable polymer-based nanocomposite materials have lately achieved popularity due to advancements in the electrical, optical, and mechanical properties of the polymer matrix, as well as their wide variety of applications in electrochemical and optical devices30. PEO is a noticeable polymer that is known as semi-crystal with a significant level of crystallinity31. As known, the chemical structure of PEO as shown in Fig. 2a consists of C–H, C–C, and C–O bonds make the reactivity and conductivity is very limited32. Filled polymers is a brilliant choice to develop new smart materials with efficient qualities, therefore polymer-metal oxide nanocomposites create novel and distinctive materials with excellent characteristics33. As consequently, in order to improve PEO’s electrical and optical characteristics, a variety of MOs with narrow band gaps and good electrical and optical functionality were chosen, including MgO34, SiO235, TiO236, NiO37, CuO38, ZnO39, and ZrO240. According to the PEO chemical structure, it has a polar group –O–, which acts as the active side of its interactions and/or association with the other materials. So, the interaction between proposed metal oxides and PEO will occur through the –O– group with the metal atom of metal oxide as shown in Fig. 2. According to the PEO chemical structure it characteristic with a polar group –O– in its, that serves as the active side of its interaction and/or association with the metal cation. As seen in Fig. 2, the interaction between suggested metal oxides and PEO will take occur via the –O– group with the metal atom of the metal oxide. The effect of metal oxide incorporation on the electrical and optical properties of PEO was investigated, with CuO emerging as the most effective dopant for enhancing conductivity and light absorption. Additionally, key electronic descriptors, including the distribution of HOMO/LUMO orbitals, TDM, band gap energy, and MESP color mapping, were analyzed in simulated models to provide deeper insights into electronic behavior. Furthermore, critical reactivity and stability parameters—such as hardness, softness, electron affinity, ionization potential, electronegativity, electrophilicity, and nucleophilicity—were evaluated to comprehensively assess the impact of metal oxides on the chemical stability, reactivity, and electronic properties of the PEO-based composites.

Physical, reactivity, stability and electronic characteristics

Distribution of HOMO/LUMO orbitals

HOMO/LUMO were determined, and Fig. 3. depicts orbital distributions based on MOs interactions. HOMO/LUMO orbital dispersion is spread throughout the whole chain of PEO. MOs interact with the PEO matrix, causing an extensive alteration in the uniform distribution of PEO HOMO/LUMO orbitals, which are redistributed and concentrated over the MO. Increased TDM, in conjunction with reduced band gap energy (∆E), boosts electrical characteristics and structural stability41. The calculated TDM and band gap energy are reported in Table 1. The exploration examines the change in TDM and band gap energy (∆E) over the whole structures. All MOs raised the TDM of PEO from 00.000 Debye to 14.100, 11.822, 16.597, 10.035, 10.482, 11.607, and 15.939 Debye for MgO, SiO2, TiO2, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2, respectively. The significant rise in TDM reflects the measured polarization generated by the MOs’ interactions with the PEO, indicating that there are a high number of dipole–dipole interactions, increasing the division of charges. As consequently, the considerable improvement in PEO reactivity and stability improves electrical characteristics, notably for electrical optical and catalytic applications. Furthermore, the band gap energy (∆E) of PEO/MgO, SiO2, TiO2, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2 significantly dropped from 8.632 eV to 8.632, 2.106, 2.642, 3.188, 1.828, 0.422, 1.433, and 3.103, respectively. The band gap data show that all MOs enhance PEO electrical characteristics, but CuO is notably efficient for improving TDM and ΔE. CuO is more reactive and conductive with PEO compared to other MOs, as seen by the significant rise in TDM and lower level of ΔE. This renders CuO an especially efficient addition for increasing composite functionality in electrical and optical devices, as well as solar cell applications. These advantages are most likely driven by CuO’s huge surface area, narrow bandgap, chemical stability, and outstanding electrical characteristics. As a result, the PEO/CuO composite offered the largest electrical improvement while still maintaining excellent stability.

Reactivity and stability describtors

Additional physical descriptors concerning reactivity and stability, such as hardness, softness, and electrophilicity, are conducted to further evaluate the impact of these MOs on PEO structure. Studying these characteristics provides a wide understanding of the influence of MOs on PEO physicochemical reactivity and stability. According to Koopmans’ approximation, these reactivity descriptors are estimated essentially based on the values of HOMO and LUMO energies42. Table 1 presents also the relative reactivity and stability characteristics, including ionization potential (IP), electron affinity (EA), hardness (η), softness (σ), electrophilic (ω), and nucleophilic (ε)27,28,29. According to Koopman’s theory, IP and EA are driven by the negative value of HOMO and LUMO energy values43. Therefore, electronegativity is generated from IP and EA using Mullikens’ hypothesis, which represents the material’s capacity to grasp electrons through a chemical bond that describe the polarization and charge division via specify the material type as giving or receiving electrons43. The improvement in electronegativity signifies improved reactivity, sensitivity, and compound stability44; hence, all MOs raised the electronegativity of PEO, particularly SiO2, CuO, and ZnO, indicating an increase in PEO’s reactivity. Similarly, hardness (η) is estimated using IP and EA values according to Koopman’s approximation, which represents the material resistance to transferring electrons. A decrease in hardness increases the ability of the material to transfer electrons, increasing its ability to interact with others and reactivity45. As demonstrated, the MOs reduced the hardness of PEO, with CuO being the most effective, reducing the hardness from 4.316 to 0.106 eV, resulting in a considerable increase in PEO’s reactivity and electron transfer. Softness is the inverse of hardness, so increasing softness increases its capacity of the material to capture electrons, indicating an increase in material reactivity46. The influence of MOs increased the softness of PEO, nevertheless ultimately the most effective MO was CuO, which increased PEO softness from 0.232 to 9.434 eV. Furthermore, electrophilicity and nucleophilicity are essential characteristics in investigating molecule behavior through interaction with other molecules such as donating and/or gapping electrons. Electrophilicity (ω), or the capacity of a substance to capture electrons, is classified as strong, medium, or weak based on its ω value47. The PEO categorized as weak electrophilic material that the ω = 0.545 eV value is less than 0.8 eV. Appropriately, all MOs boosted the electrophilicity of PEO to a strong level, with CuO showing the most substantial improvement. As a whole, the reactivity results coincided with previous TDM and band gap conclusions, revealing that PEO/CuO significantly improves PEO reactivity, stability, along with electrical and optical properties.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MESP)

MESP is a further valuable descriptor to fully comprehend chemical interactions and their electrical characteristics. MESP’s relevance emerges from its association to total charge dispersion, which is affected by the way the dipole moment, electronegativity, partial charges, and the reactive sites of chemical structure48. Figure 4 depicts the MESP of PEO, and PEO interacts with a variety of MOs, including MgO, SiO2, TiO2, NiO, CuO, ZnO, and ZrO2. Consequently, the colors that indicate MESP levels covered the molecular surface in the following order: high to low: red, orange, yellow, green, and blue. On the MESP surface, the colors are expressed as follows: red represents the greatest charge region, blue represents the lowest charge region, and green represents the neutral surface. The oxygen –O– linkage atom was shown to be the primary reason for PEO reactivity that the red color localized around it. The influence of MOs on the MESP map of PEO translated into the red color spreading along the polymer chain’s up and down branches, suggesting that PEO reactivity and surface area boosted. As it turns out, PEO’s electrical properties have improved, that overall reactivity and stability descriptors corroborate the MESP beside the band gap findings, making it appropriate for usage in a range of electronic and optical applications.

PEO/CuO/G physical, reactivity, stability and electronic characteristics

HOMO/LUMO orbitals and MESP

G as a common 2D layer within sp2-hybridized carbon, offers exceptional chemical and physical capabilities for enhanced performance owing to its physicochemical, mechanical, thermal, and electrical characteristics. G was supposed to design and/or boost a long-lasting and sustainable nanocomposite with unique electrical and thermal characteristics. Consequently, the implementation of G nanosheets remains an effective reinforce mechanism that promotes the surface area and porosity of the material, enhancing electron transfer via porous framework reflect on attraction to electrons and/or conductive properties49. Graphene have the unusual property of being able to tune the bandgap of structures, allowing them to be used in opto-electric devices, e.g., solar cells (SC), light emitting diodes (LEDs), photosensors (PS)50, or thin film transistors (FET)51. As a result, the interaction of G was considered with the highest electrical enhanced structure PEO/CuO. Further from investigating the impact of these reactions on HOMO/LUMO orbital distributions and MESP colors. The assumed interactions and the calculated HOMO/LUMO orbital distributions as well as MESP contour map represented as shown in Fig. 5. The contact of G with PEO/CuO through the –O– atom of CuO forced the HOMO/LUMO orbitals to expand over the interacting CuO and the G sheet, which ended in increased reactivity and conductivity. Additionally, as demonstrated in the contour MESP map, the red line fields flew from the –O– atom of CuO to the surface of the G sheet and increased in the inert net of carbon rings, indicating that the reactivity, porosity, and/or conductivity of the whole composite increased as well as activated the G sheet.

Reactivity and stability describtors

To investigate more deeply the impact of CuO and G on PEO properties as previously TDM, band gap energy, electronegativity, hardness, softness, electrophilicity, and nucleophilicity were calculated and listed in Table 2. The TDM of PEO/CuO/G has considerably risen to 18.794 Debye, with a 0.257 eV drop in band gap to half. These results represent the action of G, which tuned the band gap of PEO/CuO to a small band gap, increasing electron transport, reactivity, and conductivity. Creating a hybrid with CuO and G boosts electrophilicity whereas additionally enhancing and transforming the composite towards extremely strong electrically conductive substances, confirming that the presence of G sheets develops the surface area according to the porous, improving PEO reactivity and conductivity capability. PEO/CuO/G had the highest sensitivity among all the results. Overall reactivity values corroborated the MESP and HOMO/LUMO band gap outcomes, revealing that PEO/CuO/G is a highly reactive, conductive, and stable composite based on its unique electronic properties, as well as verifying and/or describing the influence of composition.

Total density of states (TDOS) and partial density of states (PDOS)

The promising PEO/CuO–GO composite was studied further to investigate the electrical and molecular properties of interconnections52. The TDOS and PDOS of PEO and PEO/CuO/G were investigated in more depth due to their potential use in investigating the variance in electronic properties, the HOMO/LUMO band gap, and interacting molecules36. The effect and interactions of GO changed the HOMO levels, shifting them near to the Fermi level from 6 to 4.9 eV, as illustrated in Fig. 6a and c. This phenomenon was coupled with a considerable shift in the separation between HOMO and LUMO levels, with LUMO levels emerging and the band gap closing as a result of the substantial molecular interactions between PEO, CuO, and G. Furthermore, Fig. 6b of PEO demonstrated a significant difference, with H − 1 s amplitudes that are higher than the O − 2p and C − 2p orbitals, as well as a normalized distribution of C − 2p, H − 1 s, and O − 2p throughout the HOMO levels. The implementation of CuO and G to the PEO orbital prompted a shift in the distribution of C − 2p, H − 1 s, and O − 2p orbitals as shown in Fig. 6d, which extended across the HOMO and LUMO levels, giving rise to H, C, and O overlapping across HOMO and LUMO levels with increasing O-2p amplitude. As an outcome of the effect of CuO and G orbitals on PEO, there is a substantial reduction of the electrons and/or energies owing to the contact through PEO’s O − 2p, which is a weak interaction. The development of this configuration is critical for interpreting the PEO/CuO/G modification of molecular responsiveness and durability; it demonstrated that more high distribution of electrons modifications is induced according to the interaction concerning PEO, CuO and G, which confirms previous study findings on band gap energy, HOMO/LUMO orbital, and MESP, indicating a boost in electrical features, conductivity, and permanence.

PEO/CuO/G composite experimental result

FTIR and XRD results

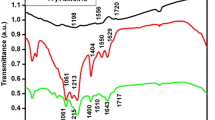

FTIR spectra were investigated in order to acquire a deeper awareness of the consequences of CuO and G on the molecular structure of PEO, as well as to confirm the interaction mechanism between PEO, CuO, and G. Figure 7a illustrates the FTIR spectra of PEO, CuO, G, and PEO/CuO/G, as well as PEO/CuO/GO nanocomposite band assignment is mentioned in Table 3. The FTIR spectrum of PEO revealed the most prevalent recognized bands for the chain structure. These characteristic PEO structural bands were assigned as C − H stretching vibrations at 2871 cm−1, followed by two vibrational bands represent the stretching and bending modes of CH2 groups at 1453 and 1340 cm−1, respectively53. The PEO chain’s prominent bands were C − O − C bonds at 1287 cm−1. This band is critical due to the regulation of polymer reactivity and the interactions that occur inside it. Finally, the band at 1099 cm−1 was identified as C − H wagging54. The FTIR spectrum of CuO NPs shows a significant band at 602 cm−1 that reveals CuO production55. The spectra of PEO/CuO/G reveals typical bands of PEO, including 2868 cm−1 for C − H, and bands at 1464 and 1411 cm−1 representing CH2 stretching and bending vibrations of the chain. A new band at 1557 cm−1 confirmed the presence of C − C of G and interaction of the sheet via a hydrogen bond. The C − O − C band shifted to a lower wavelength at 1264 cm−1, confirming the beneficial effects of CuO and G on the PEO chain and interaction through the − O − linkage. The CuO band also appeared with a shifted to lower wavenumber at 594 cm−1, confirming the composite formation between PEO, CuO, and G53.

On the other hand, Fig. 7b. illustrates the XRD patterns used to identify the composition and structure of synthesized NPs and nanocomposites. The reflection peaks of PEO appear at 2θ = 14.76°, 19.08°, 23.21°, 26.17° and 26.93° related to (110), (120), (112), (131) and (041). The XRD pattern of CuO NPs refer to the monoclinic crystal structure. Furthermore, the peaks represented at 2θ = 32.50°, 35.53°, 38.75°, 48.83°, 53.47°, 58.22°, 61.56°, 66.13°, 67.99°, 72.43°, 75.11° and 83.04° which can be attributed to the reflection planes (110), (002), (111), (-202), (020), (202), (113), (311), (113), (311), (222), respectively, which attributed to the monoclinic phase of CuO (JCPDS Card No.: 48–1548)56. The G diffraction peak is illustrated at about 2θ = 24.83°, corresponding to the (002) reflection plan57. PEO/CuO/G composite 2θ values of 19.06° (120), 23.23° (112), 26.89° (200), 35.45° (002), 38.66° (111), and 48.75° (202) are compatible with standard results and reflect the great purity of the nanocomposite. Furthermore, this complexation shows that such tree materials may be well blended and are extremely compatible during the membrane fabrication process58.

Morphology results

Figure 8 presents the morphological characteristics of pure PEO, CuO, G, and the PEO/CuO/G composite. The SEM image of pure PEO exhibits a compact, flaky morphology, with closely packed granules forming a dense structure. The observed morphology suggests a highly crystalline nature, as corroborated by XRD measurements59. This compact arrangement may influence the charge transport properties of the material, impacting its potential application as a CE in DSSCs. The SEM micrograph of CuO NPs reveals a homogeneous distribution of small spherical particles. The uniformity in size and distribution indicates effective synthesis and dispersion of CuO within the polymer matrix, which can enhance the electrocatalytic activity of the CE60. The small particle size also suggests a high surface area, which is beneficial for charge transfer efficiency in DSSCs61. For G, the SEM image displays the presence of layered agglomerates, which is a typical characteristic of graphene-based materials due to strong van der Waals interactions between individual graphene sheets. This agglomeration can affect the electrical conductivity and catalytic activity of the composite, necessitating an optimized balance of graphene content for effective performance62. The SEM micrograph of the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite reveals a well-integrated structure where CuO and graphene are distributed across the PEO surface. However, localized agglomerates of CuO and graphene are visible, which might have resulted from the relative proportions of these components within the composite matrix63. The observed agglomeration could influence the electrochemical properties of the CE by affecting electron mobility and catalytic activity. Despite this, the presence of CuO and graphene in the polymer matrix is expected to enhance the overall conductivity and electrocatalytic efficiency of the material, making it a promising candidate for DSSC applications64.

Surface roughness, electrical conductivity and optical features of CEs

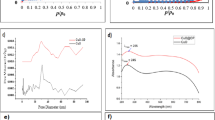

Surface roughness is a crucial factor influencing the performance of CEs in DSSCs, as it affects the effective surface area, catalytic activity, and electrode–electrolyte interface properties. A profilometry measurements was conducted to determine the average surface roughness (Ra) of pure PEO, CuO, G, and the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite, yielding values of 6.5 µm, 5.4 µm, 6.7 µm, and 8.1 µm, respectively, as seen in Fig. 9a. The surface roughness of pure PEO was measured at 6.5 µm, which is relatively high and indicative of its crystalline and compact morphology. As observed in SEM images, the flaky structure of PEO contributes to surface irregularities, resulting in moderate roughness. However, the lack of conductive pathways and limited active surface area may hinder its efficiency as a CE in DSSCs. In contrast, CuO NPs exhibited a lower roughness value of 5.4 µm. The smoother surface can be attributed to the small, uniformly dispersed spherical particles, as observed in SEM images65. The reduced roughness may enhance charge transport efficiency but could also limit the available active sites for catalytic reactions66,67. A balance between surface roughness and uniformity is crucial to optimize CE performance. Graphene demonstrated a slightly higher surface roughness of 6.7 µm. The layered structure of graphene tends to create agglomerations and stacked formations, which contribute to surface irregularities32. While graphene provides excellent electrical conductivity, excessive stacking may reduce the number of accessible active sites, impacting its catalytic activity and electrolyte diffusion properties68. The optimized PEO/CuO/G composite exhibited the highest surface roughness at 8.1 µm, reflecting its unique microstructural characteristics. The integration of CuO and graphene within the PEO matrix introduced additional surface irregularities, likely due to the formation of interconnected conductive pathways69. The enhanced roughness increases the effective surface area, which is beneficial for electrolyte diffusion and catalytic activity. However, excessive roughness can lead to uneven charge distribution, necessitating an optimized composition to achieve a balance between conductivity and electrochemical performance32,70. Overall, the increased surface roughness in PEO/CuO/G composites suggests an improved electrode–electrolyte interface, which can enhance charge transfer kinetics in DSSCs. The synergistic effects of CuO and graphene contribute to the development of a highly efficient CE material, optimizing both surface morphology and electrochemical properties70.

Electrical conductivity is a crucial parameter in assessing the performance of CEs in DSSCs, as it directly impacts charge transfer kinetics and overall device efficiency. The electrical resistance was measured using a four-point probe (4PP) resistivity tester (EQ-JX2008-LD). To ensure accuracy and reproducibility, the average electrical resistance of each PAni composite was determined based on measurements taken from more than 10 different locations. The electrical conductivities of pure PEO, CuO, G, and the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite were measured, yielding values of 4.63 S/m, 11.45 S/m, 10.31 S/m, and 12.56 S/m, respectively, as seen in Fig. 9b. These findings demonstrate the significant enhancement in electrical conductivity upon incorporating CuO and graphene into the PEO matrix. Pure PEO exhibited the lowest electrical conductivity of 4.63 S/m, which is expected due to its intrinsic insulating nature and highly crystalline morphology, as observed in the SEM analysis. The compact and flaky structure of PEO limits charge carrier mobility, thereby restricting its ability to facilitate efficient electron transport in DSSCs. CuO NPs, with an electrical conductivity of 11.45 S/m, significantly outperform PEO. This improvement can be attributed to the semiconducting nature of CuO, which provides moderate charge transport properties. The presence of CuO enhances electron mobility due to its p-type conduction behavior, making it a promising material for electrocatalytic applications71. Graphene, a well-known carbon-based material with exceptional electrical properties, exhibited a conductivity of 10.31 S/m. Although graphene possesses inherently high electrical conductivity, the observed value in this study is lower than expected, likely due to agglomeration, as seen in the SEM micrographs. The stacking of graphene sheets reduces the available conductive pathways, thereby limiting charge transport efficiency68.

The optimized PEO/CuO/G composite exhibited the highest electrical conductivity (12.56 S/m), highlighting the synergistic interaction between CuO and graphene within the polymer matrix. The incorporation of CuO enhances charge transport, while graphene provides additional conductive pathways, effectively minimizing charge recombination72. Although minor agglomeration was observed in SEM images, the well-dispersed CuO and graphene nanoparticles establish a conductive network, facilitating efficient electron transfer73. The significant increase in conductivity from pure PEO to PEO/CuO/G underscores its potential as an advanced CE material for DSSCs. The enhanced electrical conductivity is expected to improve charge collection and transport at the electrode–electrolyte interface, ultimately leading to superior photovoltaic performance74. This experimental trend aligns with the theoretical findings, where the higher TDM value (18.794 Debye) of PEO/CuO/G suggests increased charge polarization within the composite, indicating enhanced charge transfer properties. Experimentally, this improved charge transport is reflected in the observed rise in electrical conductivity (12.56 S/m), which is attributed to strong electronic interactions between CuO and graphene, forming a well-interconnected conductive network. This correlation between theoretical and experimental results reinforces the conclusion that the synergistic effects of CuO and graphene significantly enhance charge transport, reduce recombination losses, and improve the overall efficiency of DSSCs.

The UV–vis absorbance spectra presented in the graph provide a comparative analysis of the optical behavior of PEO/CuO and PEO/CuO/G within the wavelength range of 350–800 nm, as displayed in Fig. 9c. The PEO/CuO composite exhibits a broad absorption band spanning 500–700 nm, with a noticeable peak around 600–650 nm. This absorption is characteristic of CuO NPs, which have strong visible-light absorption due to their narrow bandgap and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects. The interaction of PEO with CuO NPs may also influence the absorption profile, contributing to enhanced charge separation and potential improvements in photoelectrochemical performance75. In contrast, the PEO/CuO/G composite shows a distinct optical response, with minimal absorbance in the 400–600 nm range but a dramatic increase in absorption beyond 700 nm, extending into the near-infrared (NIR) region. This behavior can be attributed to the incorporation of graphene, which significantly alters the electronic structure and light-harvesting ability of the composite76. Graphene’s delocalized π-electron system facilitates enhanced light absorption by improving charge carrier mobility and reducing recombination losses77. The strong NIR absorbance observed in PEO/CuO/G suggests improved photon capture in longer wavelengths, which is particularly beneficial in PV and photocatalytic applications78.

The observed spectral shift in PEO/CuO/G compared to PEO/CuO highlights the impact of graphene in modifying the optical properties of the material. The enhanced broadband absorbance in the NIR region suggests improved light-harvesting efficiency, which could be advantageous in applications such as DSSCs, optoelectronic devices, and photothermal conversion systems. Additionally, the increased interaction between CuO NPs and graphene may facilitate better electron transport, reducing charge recombination and enhancing overall device performance. These findings indicate that PEO/CuO/G holds great potential for advanced energy-harvesting and environmental applications.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data

The EIS examination reveals critical information about the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and series resistance (Rs) of the various CEs, allowing for a better understanding of their interfacial charge transport behaviour79. The electrical characteristics of the produced DSSCs were evaluated using Nyquist plots, which are generally made up of semicircles that depict charge transfer processes at the electrode–electrolyte interface, as seen in Fig. 10. To extract Rct and Rs values, an equivalent circuit model was fitted to the real and imaginary impedance components (ReZ and ImZ, respectively). Table 4 shows that the PEO/CuO/G composite possessed the lowest Rct (14.02 Ω) and Rs (16.87 Ω) among tested CEs, showing greater charge transfer performance and lower internal resistance. The observed trend in Rs values shows that including CuO and graphene into the PEO matrix improves electronic conductivity and electrode–electrolyte interaction, allowing for efficient charge transfer80,81. The pristine PEO CE had the greatest Rct (29.81 Ω), indicating slow charge transfer kinetics and minimal electrocatalytic activity. The addition of CuO and graphene to the CE framework lowered Rct, indicating their significance in improving electron mobility and catalytic efficiency for the \({\text{I}}_{3}^{-}\)/\({\text{I}}^{-}\) redox process82.

The synergistic impact of CuO and graphene in the PEO/CuO/G composite is critical for enhancing electrocatalytic activity, which contributes to increased PV efficiency. The addition of graphene nanosheets improves charge carrier routes, reducing charge recombination and forming a highly conductive network for fast electron transport. CuO NPs catalyse the reduction of \({\text{I}}_{3}^{-}\) and improve electrochemical kinetics at the CE/electrolyte contact. The drop in Rct (from 29.81 Ω for pure PEO to 14.02 Ω for PEO/CuO/G) suggests improved charge separation and electron transport, leading to improved DSSC PV performance. PEO/CuO/G (16.87 Ω) has improved charge transport capabilities compared to pure PEO (30.21 Ω), CuO (22.35 Ω), and graphene (19.97 Ω). The drop in Rs indicates enhanced electrical contact at the FTO/CE interface, lowering ohmic losses and increasing overall DSSC efficiency. However, excessive nanomaterial alteration or agglomeration might result in a rise in Rs, thereby restricting the electrode’s catalytic activity83,84. In general, the trends in the EIS data show that the PEO/CuO/G CE has superior charge transport kinetics, lower resistance, and increased catalytic efficiency, making it a highly promising material for DSSC applications80. The increased electroactive surface area, enhanced electron mobility, and efficient electrocatalytic reduction of the electrolyte redox couple all contribute to the study’s higher PV efficiency (7.42%). These findings highlight the potential of hybrid polymer-metal oxide composites as next-generation CEs, further advancing the development of high-performance DSSCs81.

DSSCs performance trends and observations

The PV performance of DSSCs is primarily governed by key parameters such as short-circuit current density (Jsc), fill factor (FF), and overall power conversion efficiency (η). The CE plays a crucial role in facilitating charge transfer and reducing charge recombination, directly influencing these parameters. The DSSCs were fabricated using CEs composed of pure PEO, CuO, G, and the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite, and their PV parameters were measured as tabulated in Table 4. Additionally, to ensure the reproducibility and repeatability of the fabricated DSSCs, a minimum of six distinct devices were manufactured for each designed CE, demonstrating the highest performance among the composite-based CEs. The obtained data, presented in Table 4, confirm the consistent performance and reliability of each DSSC configuration. Figure 11 demonstrates the resultant photocurrent distribution–photovoltage (J–V) profile curves. The DSSC utilizing pure PEO as the CE exhibited the lowest performance, with Jsc = 11.428 mA/cm2, FF = 63.4%, and efficiency = 4.33%. This relatively poor performance is attributed to the low electrical conductivity (4.63 S/m) of PEO, which hinders charge transfer at the electrode–electrolyte interface85. Additionally, the compact and flaky morphology of PEO, as observed in SEM, limits the active surface area, further reducing electrocatalytic activity and electron mobility86. Meanwhile, introducing CuO NPs into the CE resulted in an improvement in all solar parameters. The Jsc increased to 12.746 mA/cm2, FF improved to 64.7%, and efficiency rose to 4.83%. The enhancement can be attributed to the higher electrical conductivity of CuO (11.45 S/m) and its ability to act as a catalyst, improving charge transfer kinetics74. Moreover, the uniform dispersion of CuO NPs, as observed in SEM, provides more active sites for electrolyte interaction, reducing charge recombination losses.

Moreover, the DSSC incorporating graphene as the CE showed a further enhancement in PV performance, with Jsc reaching 14.656 mA/cm2, FF up to 63.1%, and efficiency rising to 5.69%. The superior electrical conductivity of graphene (10.31 S/m) facilitates more efficient charge transport, reducing the series resistance of the cell. However, the SEM analysis revealed some degree of graphene agglomeration, which may partially limit charge transfer efficiency87. Despite this, the high surface area of graphene enables enhanced electrolyte interaction, leading to improved catalytic activity67,87. The highest PV performance was achieved using the optimized PEO/CuO/G composite, with Jsc = 16.916 mA/ cm2, FF = 65.1%, and efficiency = 7.42%. This improvement results from the synergistic effect of CuO and graphene within the PEO matrix, providing a well-balanced combination of conductivity, catalytic activity, and surface morphology88. The increased electrical conductivity (12.56 S/m) of the composite ensures rapid charge transfer, while the high surface roughness (8.1 µm) enhances electrolyte diffusion and reaction kinetics. The SEM images confirm the formation of an interconnected conductive network, further optimizing charge transport pathways82,85. In summary, the gradual enhancement of DSSC performance from pure PEO to CuO, graphene, and ultimately the PEO/CuO/G composite highlights the effectiveness of incorporating CuO and graphene as co-modifiers in the CE89. The optimized composite structure enhances charge transfer, minimizes recombination losses, and increases the available active sites for electrocatalytic activity, leading to a substantial improvement in short-circuit current density, fill factor, and overall power conversion efficiency68. These findings confirm that PEO/CuO/G is a promising CE material for high-performance DSSCs, offering improved electrical properties and surface characteristics81.

Table 5 compares the photocurrent–voltage properties of several polymer-based metal oxide composites used as electrolytes or CEs in DSSCs that have been documented in the literature. They compare their PV efficiency to the DSSC created in this work, which uses a modified PEO/CuO/G composite. According to the findings, a number of DSSCs demonstrated reduced efficiency in contrast to the PEO/CuO/G-based DSSC, which had a conversion efficiency of 7.42%. The noticeably greater surface area and more active sites available for electrocatalytic activity in the constructed PEO/CuO/G CEs are probably responsible for the observed improvement in PV performance. This, in turn, improves dye molecule adsorption and raises device efficiency overall90.

Conclusion

This work provides a comprehensive theoretical and experimental investigation into the role of PEO/CuO/G composites as CEs in DSSCs. The systematic analysis of morphological, electrical, and electrochemical properties demonstrated the significant improvements induced by the incorporation of CuO and graphene within the PEO matrix. The optimized PEO/CuO/G composite exhibited superior electrical conductivity (12.56 S/m), higher surface roughness (8.1 µm), and an interconnected nanostructured morphology, facilitating enhanced electron transport and catalytic activity. The PV performance of DSSCs fabricated with PEO/CuO/G CEs showed a notable increase in efficiency (7.42%) compared to pure PEO-based DSSCs (4.33%), owing to the synergistic interaction of CuO and graphene, which effectively reduced charge recombination and enhanced electrochemical stability. Theoretical modeling supported these experimental results, confirming an increase in electron mobility, lower internal resistance, and improved charge collection efficiency within the composite electrode structure. These findings underscore the potential of PEO/CuO/G composites as a cost-effective and high-performance alternative to conventional platinum-based CEs. Future work will focus on further optimizing the composite formulation and exploring its long-term stability under real-world operating conditions. This research lays the groundwork for the advancement of DSSC technology, contributing to the development of sustainable and efficient PV devices.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Huang, X. et al. Efficient and stable Z907-based dye-sensitized solar cells enabled by suppressed charge recombination and photocatalytic activity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12(34), 13007–13016 (2024).

He, S. et al. Holistically optimizing charge carrier dynamics enables high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells and photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14(38), 43576–43585 (2022).

He, S. et al. Holistically modulating charge recombination via trisiloxane surface treatment for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Alloys Compd. 896, 162864 (2022).

Zhu, S., Wei, W., Chen, X., Jiang, M. & Zhou, Z. Journal of Solid State Chemistry Hybrid structure of polyaniline / ZnO nanograss and its application in dye-sensitized solar cell with performance improvement. J. Solid State Chem. 190, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2012.02.028 (2012).

Gülena, M. Rapid synthesis of SrTiO 3 nanocubes and replacement of the high-cost platinum electrode with SrTiO 3 / PANI nanocomposite in dye-sensitized solar cells. Synth. Met. 293, 117297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2023.117297 (2023).

Ri, J. H., Jin, J., Xu, J., Peng, T. & Ryu, K. I. L. Preparation of iodine-free ionic liquid gel electrolyte using polyethylene oxide (PEO)-polyethylene glycol (PEG) and its application in Ti-foil-based dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 201, 251–259 (2016).

Dissanayake, M., Rupasinghe, W. N. S., Seneviratne, V. A., Thotawatthage, C. A. & Senadeera, G. K. R. Optimization of iodide ion conductivity and nano filler effect for efficiency enhancement in polyethylene oxide (PEO) based dye sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 145, 319–326 (2014).

Morsi, M. A., Abdelrazek, E. M., Tarabiah, A. E. & Salim, E. Preparation and tuning the optical and electrical properties of polyethylene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol/poly (3, 4-thylenedioxythiophene): polystyrene sulfonate/CuO-based quaternary nanocomposites for futuristic energy storage devices. J. Energy Storage 80, 110239 (2024).

Soliman, W. & Shahat, M. A. Optimizing the thermophysical qualities of innovative clay–rGO composite bricks for sustainable applications. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48966-w (2023).

Rashwan, G. M., Ebnalwaled, A. A., Saad, E. M. & Shahat, M. A. Ca/Sn concentration-dependent enhancement of barium titanate ferroelectric performance: A dielectric and microstructural study. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 109(3), 707–719 (2024).

Arthisree, D. & Madhuri, W. Optically active polymer nanocomposite composed of polyaniline, polyacrylonitrile and green-synthesized graphene quantum dot for supercapacitor application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45(16), 9317–9327 (2020).

Hashim, A., Al-Khafaji, Y. & Hadi, A. Synthesis and characterization of flexible resistive humidity sensors based on PVA/PEO/CuO nanocomposites. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 20(6), 530–536 (2019).

Refaat, A. et al. Geometrical, vibrational and physical properties of polyvinyl chloride nanocomposites: Molecular modeling approach. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 18(08), 1950037 (2019).

Hegazy, M. A. et al. Electronic and physical studies for Teflon FEP as a thermal control in low earth orbit reinforced with ZnO and SiO 2 nanoparticles. J. Mol. Model. 27, 1–8 (2021).

Menazea, A. A. et al. Chitosan/graphene oxide composite as an effective removal of Ni, Cu, As, Cd and Pb from wastewater. Comput. Theor. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112980 (2020).

Badry, R. et al. Electronic properties of polyvinyl alcohol/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposites. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 10(5), 6427–6435 (2020).

Ahmed, H. & Hashim, A. Geometry optimization, optical and electronic characteristics of novel PVA/PEO/SiC structure for electronics applications. SILICON 13(8), 2639–2644 (2021).

Gomaa, F., Osman, O., Ezzat, H. & Ibrahim, M. Molecular spectroscopic analyses of soil close to Nile Delta region. Quantum Matter 5(2), 263–267 (2016).

Shahat, M. A., Ahmed, Y. M. Z., Ghitas, A., El-Shater, A. & Soliman, W. Improving the thermophysical aspects of innovative clay brick composites for sustainable development via TiO2 and rGO nanosheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 401, 132981 (2023).

El-Hossary, F. M. et al. Cold RF oxygen plasma treatment of graphene oxide films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-06123-x (2021).

El-Hossary, F. M., Ghitas, A., El-Rahman, A. M. A., Shahat, M. A. & Fawey, M. H. The effective reduction of graphene oxide films using RF oxygen plasma treatment. Vacuum https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2021.110158 (2021).

El-Hossary, F. M. et al. Enhancement of Adhesion Force and Surface Conductivity of Graphene Oxide Films Using Different Solvents. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/762/1/012001 (2020).

M.J. Frisch, G.W. Trucks, H.B. Schlegel, G.E. Scuseria, M.A. Robb, J.R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, G.A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Caricato, X. Li, H.P. Hratchian, A.F. Izmaylov, J. Bloino, G. Zheng, J.L. Sonnenberg, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, J.A. Montgomery Jr., J.E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. Bearpark, J.J. Heyd, E. Brothers, K.N. Kudin, V.N. Staroverov, T. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. Rendell, J.C. Burant, S.S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, N. Rega, J.M. Millam, M. Klene, J.E. Knox, J.B. Cross, V. Bakken, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R.E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A.J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J.W. Ochterski, R.L. Martin, K. Morokuma, V.G. Zakrzewski, G.A. Voth, P. Salvador, J.J. Dannenberg, S. Dapprich, A.D. Daniels, O. Farkas, J.B. Foresman, J.V. Ortiz, J. Cioslowski, D.J. Fox, Gaussian 09, Revision C.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2010..

Raghavachari, K. Perspective on ‘Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange’ Becke AD (1993) J Chem Phys 98: 5648–52. Theor. Chem. Acc. 103, 361–363 (2000).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37(2), 785 (1988).

Vosko, S. H., Wilk, L. & Nusair, M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: a critical analysis. Can. J. Phys. 58(8), 1200–1211 (1980).

Elhaes, H., Ibrahim, A., Osman, O. & Ibrahim, M. A. Molecular modeling analysis for functionalized graphene/sodium alginate composite. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 14825 (2024).

Adekoya, O. C., Adekoya, G. J., Sadiku, E. R., Hamam, Y. & Ray, S. S. Application of DFT calculations in designing polymer-based drug delivery systems: An overview. Pharmaceutics 14(9), 1972 (2022).

Mizera, A., Dubis, A. T. & Łapiński, A. Density functional theory studies of polypyrrole and polypyrrole derivatives; substituent effect on the optical and electronic properties. Polymer (Guildf). 255, 125127 (2022).

Ezzat, H. A. et al. DFT and QSAR studies of PTFE/ZnO/SiO2 nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9696 (2023).

Arya, A. et al. PEO/PVDF-based gel polymer electrolyte by incorporating nano-TiO2 for electrochromic glass. J. Compos. Mater. 76(1), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104373 (2019).

Shahat, M. A., Ibrahim, M. A., Ghitas, A. & Ezzat, H. A. Designing innovative PAni-based adsorbents for CO2 capture via in-situ nitrogen plasma modification for sustainable development. J. CO2 Util. 84, 102830 (2024).

Sikdar, S., Menezes, P. V., Maccione, R., Jacob, T. & Menezes, P. L. Plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) process—processing, properties, and applications. Nanomaterials 11(6), 1375 (2021).

Sabry, N. M., Badry, R., Abdel-Gawad, F. K., Elhaes, H. & Ibrahim, M. A. Electronic structure, global reactivity descriptors and nonlinear optical properties of glycine interacted with ZnO, MgO and CaO for bacterial detection. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 22801 (2024).

Sabry, N. M., Badry, R., Ibrahim, M. A. & Ezzat, H. A. Role of SiO2, TiO2, and Fe3O4 adsorbed on glycine for remediation of heavy metals and antibacterial activity in water. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27617 (2024).

Shahat, M. A., Aladim, A. K., Sebak, M. A. & Ezzat, H. A. Developing innovative PVA/ TiO2-based adsorbents for CO2 capture via multiple metal oxide dopants for sustainable development. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 174, 113947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2025.113947 (2025).

Ezzat, H. A. et al. Semiempirical molecular modeling analyses for graphene/nickel oxide nanocomposite. Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 9, 1459 (2020).

Shahin, N. A. M., Abd El Hamid, R. & Ezzat, H. A. Effect of CuO on the molecular structural, optical, and electronic properties of polyvinyl pyrrolidone: experimental and DFT approaches. Egypt. J. Chem. 67(2), 571–580 (2024).

Ibrahim, A., El Aal, M. A. & Ezzat, H. A. Functionalized graphene quantum dots with ZnO as a humidity sensor. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56(3), 467 (2024).

Petrik, P. et al. Optical properties of Zr and ZrO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 421, 744–747 (2017).

Ezzat, H. A. et al. Molecular modeling analyses of functionalized cellulose. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27698 (2024).

Bhatia, M. An overview of conceptual-DFT based insights into global chemical reactivity of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs). Comput. Toxicol. p 100295, 2023.

Obot, I. B., Macdonald, D. D. & Gasem, Z. M. Density functional theory (DFT) as a powerful tool for designing new organic corrosion inhibitors. Part 1: An overview. Corros. Sci. 99, 1–30 (2015).

Obot, I. B., Kaya, S., Kaya, C. & Tüzün, B. Density Functional Theory (DFT) modeling and Monte Carlo simulation assessment of inhibition performance of some carbohydrazide Schiff bases for steel corrosion. Phys. E Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostructures 80, 82–90 (2016).

Gázquez, J. L. Hardness and softness in density functional theory. Chem. Hardness, pp 27–43, (1993).

Chattaraj, P. K. & Roy, D. R. Update 1 of: Electrophilicity index. Chem. Rev. 107(9), PR46–PR74 (2007).

Pal, R. & Chattaraj, P. K. Electrophilicity index revisited. J. Comput. Chem. 44(3), 278–297 (2023).

Politzer, P., Laurence, P. R. & Jayasuriya, K. Molecular electrostatic potentials: An effective tool for the elucidation of biochemical phenomena. Environ. Health Perspect. 61, 191–202 (1985).

Zhong, M. M., Yuan, H. K., Huang, C. & Wang, G. Electronic properties of porous graphene and its hydrogen storage potentials. J. Alloys Compd. 766, 104–111 (2018).

Vankalayapati, S. et al. Design of a dual-metal layer SPR biosensor for enhanced melamine detection using black phosphorus nanomaterials. Plasmonics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-024-02716-4 (2024).

Huang, H. et al. The chemistry and promising applications of graphene and porous graphene materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30(41), 1909035 (2020).

Li, S., Wan, H., Lin, J. & Min, J. Physicochemical interactions between amorphous metal oxide and polymer in metal–polymer hybrid materials. Mater. Des. 230, 111993 (2023).

Sethupathy, M., Sethuraman, V., Raj, J. A., Muthuraja, P., Manisankar, P. Electrospun polyethylene oxide (PEO) nanofiber membranes based polymer electrolyte for dye sensitized solar cell. in AIP Conference Proceedings, American Institute of Physics, pp 253–257 (2014).

Pucić, I. & Jurkin, T. FTIR assessment of poly (ethylene oxide) irradiated in solid state, melt and aqeuous solution. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 81(9), 1426–1429 (2012).

Ezzat, H. A., Hegazy, M. A., Nada, N. A., Osman, O. & Ibrahim, M. A. Studying the optical and thermal properties of Cs/ZnO and Cs/ZnO/GO hybrid nanocomposites. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 135, 113244 (2023).

Siddiqui, H., Qureshi, M. S. & Haque, F. Z. Surfactant assisted wet chemical synthesis of copper oxide (CuO) nanostructures and their spectroscopic analysis. Optik (Stuttg) 127(5), 2740–2747 (2016).

Andonovic, B., Grozdanov, A., Paunović, P. & Dimitrov, A. T. X-ray diffraction analysis on layers in graphene samples obtained by electrolysis in molten salts: a new perspective. Micro Nano Lett. 10(12), 683–685 (2015).

Cao, Y.-C. et al. A poly (ethylene oxide)/graphene oxide electrolyte membrane for low temperature polymer fuel cells. J. Power Sources 196(20), 8377–8382 (2011).

Hashim, A. & Hadi, A. Synthesis and characterization of (MgO–Y2O3–CuO) nanocomposites for novel humidity sensor application. Sens. Lett. 15(10), 858–861 (2017).

Kanimozhi, S., Prabu, K. M., Thambidurai, S. & Suresh, S. Dye-sensitized solar cell performance and photocatalytic activity enhancement using binary zinc oxide-copper oxide nanocomposites prepared via co-precipitation route. Ceram. Int. 47(21), 30234–30246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.203 (2021).

Almutairi, F. N., Ghitas, A., Alanazi, H. & Shahat, M. A. Gamma-irradiated Chitosan / PVA / TiO 2 catalytic counter electrodes for enhanced dye-sensitized solar cell ( DSSC ) performance. Synth. Met. 311, 117841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2025.117841 (2025).

Khalili, S., Afkhami, A. & Madrakian, T. Electrochemical simultaneous treatment approach: Electro-reduction of CO2 at Pt/PANI/ ZnO paired with wastewater electro-oxidation over PbO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 328, 122545 (2023).

Sebak, M. A., Aladim, A. K., Mostafa, M. & Shahat, M. A. Multi-level oxygen plasma treatment nanoarchitectonics on chitosan/PVA/TiO2 composite-based absorber layer network for efficient polymer solar cells. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-024-03542-1 (2024).

Aida Mohamed, N., Sieh Kiong, T., Fazli Ismail, A. & Mat Teridi, M. A. Novel gamma-ray enhanced TiO2 nanoparticles photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 642, 158602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.158602 (2024).

Hameed, S. T., Qahtan, T. F., Abdelghany, A. M. & Oraby, A. H. ZnO/CuO nanocomposite-based carboxymethyl cellulose/polyethylene oxide polymer electrolytes for energy storage applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 22, 531–540 (2023).

Enoch, K. et al. Enhanced mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol electrospun nanofibers by incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets. Carbohydr. Polym. 227, 123071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103178 (2023).

Shahat, M. A., Ghitas, A., Almutairi, F. N. & Alresheedi, N. M. Oxygen enriched PAni - based counter electrode network toward efficient dye - sensitized solar cells (DSSCs ). Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67055-0 (2024).

Mostafa, M. M., Aladim, A. K., Sebak, M. A. & Shahat, M. A. Efficient dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) via nitrogen plasma-enriched chitosan/ PVA/ rGO blend-based counter electrode compositions. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-024-03438-0 (2024).

Meera, K. & Ramesan, M. T. Modulating the properties of carboxymethyl chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanocomposites with aluminium oxy hydroxide: A comprehensive study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 282, 137034 (2024).

Alresheedi, N. M., Ghitas, A., Almutairi, F. N. & Shahat, M. A. Optimizing the efficiency of polymer solar cells based on core-shell PAni/ ZnO composites utilizing argon plasma treatment. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 35(1), 123–140 (2024).

Shahat, M. A., Ibrahim, M. A., Ghitas, A. & Ezzat, H. A. Advancements in water remediation : Harnessing PAni-based carbon composites for efficient dyes removal. J. Mol. Struct. 1327, 141220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.141220 (2025).

Ali, A., Bano, S., Priyadarshi, R. & Negi, Y. S. Effect of carbon based fillers on properties of Chitosan/PVA/βTCP based composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 15, 173–182 (2019).

Soliman, W., Ahmed, Y. M. Z., Ghitas, A., El-Shater, A. & Shahat, M. A. Green building development utilising modified fired clay bricks and eggshell waste. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 3367 (2025).

Sebak, M. A., Aladim, A. K., Mostafa, M. M. & Abdelhamid Shahat, M. Improving the efficiency of polymer solar cells based on chitosan/PVA/rGO composites via gamma-irradiated treatment of rGO nanoparticles. Solid State Sci. 159, 107773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2024.107773 (2025).

Korell, L. et al. On the structural evolution of nanoporous optically transparent CuO photocathodes upon calcination for photoelectrochemical applications. Nanoscale Adv. 6(11), 2875–2891 (2024).

Kamanna, K., Amaregouda, Y. & Kumar, M. Chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol-based nanocomposite films incorporated with L-Glu surface functionalized ZnO NPs: Physicochemical, photocatalytic, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties evaluation. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 20, 100861 (2023).

Alharbi, E. M. & Rajeh, A. Development of dielectric, thermal, optical, and electrical properties of carboxymethyl cellulose/polyethylene oxide/MnFe2O4 nanocomposites for flexible energy storage and optical applications. Ceram. Int. 50(23), 49871–49879 (2024).

Nguyen, L. D. et al. An electrochemical sensor based on polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan-thermally reduced graphene composite modified glassy carbon electrode for sensitive voltammetric detection of lead. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 345, 130443 (2021).

da Cunha, H. O., Leite, A. M. B., Ramesh, P. S., Suresh Babu, R. & de Barros, A. L. F. Improved solar cells efficiency with TiO2/CuO nanocomposite as photoanode sensitized by natural dyes from scarlet eggplant, pitomba and black grapes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 36(1), 1–20 (2025).

Pradhan, S. C. & Soman, S. Effect of thickness on charge transfer properties of conductive polymer based PEDOT counter electrodes in DSSC. Results Surfaces Interfaces 5, 100030 (2021).

Rawat, P., Prajapati, R. K., Meena, G. K. & Saroj, A. L. Enhancing the performance of Chitosan/PVP based bio-polymer electrolyte incorporated with SiO2 nano-particles in dye-sensitized solar cell. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 308, 117603 (2024).

Muhammad, F. H. & Winie, T. Influence of 1-methyl-3-propylimidazolium iodide ionic liquid on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cell using hexanoyl chitosan/poly (vinyl chloride) based polymer electrolyte. Optik (Stuttg). 208, 164558 (2020).

Ashok, A. et al. Bandgap engineering of CuO/TiO2 nanocomposites and their synergistic effect on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 148, 114896 (2024).

Mukhokosi, E. P. et al. Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles from Cucurbita maxima leaf extract; a platinum free counter electrode for dye sensitized solar cells. J. Niger. Soc. Phys. Sci. https://doi.org/10.46481/jnsps.2025.2309 (2025).

El-Hossary, F. M., Ghitas, A., Abd El-Rahman, A. M., Ebnalwaled, A. A. & Shahat, M. A. Characterization and Performance of PAni-TiO2 Photovoltaic Cells Treated by RF Plasma. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 956, 12003 (2020).

Ferrag, C., Noroozifar, M., Modarresi-Alam, A. R. & Kerman, K. Graphene oxide hydrogel electrolyte for improving the performance of electropolymerized polyaniline solar cells. J. Power Sources 542, 231796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.231796 (2022).

Pud, A. A. et al. On the importance of interface interactions in core-shell nanocomposites of intrinsically conducting polymers. Semicond. Physics Quantum Electron. Optoelectron. 22(4), 470–478 (2019).

El-Hossary, F. M. et al. Effect of UV-activated TiO2 nanoparticles on the properties and performance of PAni-TiO2 nanocomposite films for solar cell applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 956, 12015 (2020).

Areerob, Y. et al. Novel gamma-irradiated chitosan-doped reduced graphene-CuInS2 composites as counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 12(24), 15427–15434. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra01749k (2022).

Sebak, M. A., Aladim, A. K., Mostafa, M. M. & Abdelhamid Shahat, M. Improving the efficiency of polymer solar cells based on chitosan/PVA/rGO composites via gamma-irradiated treatment of rGO nanoparticles. Solid State Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2024.107773 (2025).

Najihah, M. Z., Aizamddin, M. F., Saaid, F. I. & Winie, T. Enhanced efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) with polyaniline-decorated FeCo2O4 counter electrodes: Synthesis, characterization, and performance analysis. Curr. Appl. Phys. 72, 28–38 (2025).

Kumar, A. et al. Improving the properties of Pt-free dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) by PEDOT: PSS/SnSe-rGO-based counter electrode: Exploring the electrocatalytic activity. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 185, 109009 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics (NRIAG) of Egypt (11421) and National Research Center (NRC) of Egypt (12622).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hend A. Ezzat: Modeling Structure Assignments, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hanan Elhaes and Medhat A. Ibrahim: Supervision, Formal analysis. M. Abdelhamid Shahat: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ezzat, H.A., Elhaes, H., Ibrahim, M.A. et al. Theoretical and experimental investigation of a CuO and graphene embedded polyethylene oxide counter electrode for efficient DSSCs. Sci Rep 15, 25049 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98930-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98930-z