Abstract

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a serious public health concern in China. Accurately forecasting HFMD and providing forecast uncertainty is significant for decision making by public health workers. However, existing studies have mainly focused on the accuracy of point predictions, with limited research using probabilistic predictions to provide uncertainty. In this study, we used Bayesian additive regression tree probabilistic model for point forecasting and providing forecasting intervals and compared the performance with ARIMA model based on the monthly number of HFMD cases in seven regions of mainland China from June 2008 to December 2018. Compared with ARIMA model, the mean values of MAPE and RMSE of BART model were 42.463 and 4124.997, which decreased by 73.465% and 16.332%, and the mean value of PCC was 0.921, which improved by 10.432%. The interval prediction results showed that the BART model had the smallest CWC values in study areas, covering the actual values with a narrower interval at the 95% confidence level. The BART probabilistic model is suitable for HFMD surveillance at the provincial level in mainland China because of its high point and interval prediction accuracy and strong generalization ability, which helps public health workers in decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) is a global childhood infectious disease caused by various enteroviruses1. In the past decades, there have been several outbreaks of HFMD in mainland China2,3,4,5. It is estimated that HFMD resulted in 75,881 disability-adjusted life years lost annually in mainland China6. There are about 18.2 million cases of HFMD were reported in mainland China from 2008 to 20177. Moreover, the HFMD incidence has been at the top of the list of notifiable infectious diseases in China.

There is no specific drug for the treatment of HFMD8. For the prevention of HFMD, an inactivated enterovirus 71 (EV-A71) vaccine for HFMD has been developed in China. However, for all children, the vaccine is not mandatory and the cost of vaccination is not subsidized by the government, resulting in low vaccine coverage9. In addition, the vaccine is not protective against other types of HFMD10. There was no significant decrease of HFMD cases after the vaccine entered the market in 201611. Therefore, it is critical to accurately forecast HFMD trends, which can monitor the peak incidence in advance and is very meaningful for public health workers to prevent and control HFMD.

Recent advances in predictive modeling have explored diverse approaches, including traditional time-series methods (e.g., ARIMA12,13), machine learning (e.g., support vector regression14, LSTM networks15), and hybrid models integrating climatic covariates16,17. Traditional statistical models, such as seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA), have been widely applied due to their interpretability and effectiveness in capturing temporal patterns. Xu et al. constructed a SARIMA model for Quzhou City and demonstrated the applicability of the SARIMA model in the prediction of HFMD13. Machine learning techniques are favored for their ability to handle complex nonlinear relationships in infectious disease data. Yoshida et al. showed that the LSTM method can estimate the future epidemic pattern of HFMD in Japan15. Meanwhile, Wan et al. proposed a hybrid ARIMA-EEMD-LSTM model, combining decomposition techniques with deep learning to enhance prediction stability16. In conclusion, these studies have focused on deterministic forecasting, focusing on the accuracy of point forecasts. This is limited because when public health workers make interventions based on predictions, they focus not only on accuracy but also on reliability18. Therefore, in practice, providing forecasting uncertainty under forecasting accuracy is particularly important to public health intervention makers.

The uncertainty in forecasting is commonly reflected by the forecast interval. The forecast interval can be estimated using probabilistic models or based on the statistical properties of the model error when analyzing historical data19. In this study, we propose to use the Bayesian additive regression tree (BART) probabilistic model to forecast the HFMD trends and to evaluate the uncertainty of its forecasts.

The BART is a ‘sum-of-trees’ model combining Bayesian ideas and decision tree algorithms, where each tree fits residuals that are not explained by the rest of the trees20. It assigns priors for the parameters of the tree and draws consecutive samples from the posterior to achieve the prediction. The point estimates are obtained by taking the average of all these samplings. The corresponding quantiles of the sampling provide the uncertainty interval. The BART showed great forecasting performance in PM2.5 concentration21, genome-wide22, and solar radiation prediction23. However, the BART has not been applied in the forecasting of infectious diseases.

The purpose of this study was to explore the application of the BART model for forecasting HFMD in China. This study used the ARIMA model as the baseline model. First, point prediction performance was compared to assess the predictive accuracy of the BART model for monthly HFMD cases. Second, we calculated prediction intervals at the 95% confidence level to assess interval predictive ability. This study is the first to explore the accuracy and uncertainty of HFMD point prediction from a practical application perspective, expecting to contribute to the prediction of HFMD and further to decision-making in the public health department.

Materials and methods

HFMD surveillance data

Previous studies divided the geographic regions of mainland China into seven regions, as Northeast, North, Northwest, East, Middle, Southwest, and South1. In this study, we selected study areas from seven regions, namely Heilongjiang (Northeast), Shanxi (North), Gansu (Northwest), Shandong (East), Henan (Middle), Sichuan (Southwest), and Guangdong (South). The monthly HFMD case data for these areas from June 2008 to December 2018 was obtained from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention through the Public Health Sciences Data Center (https://www.phsciencedata.cn/).

We fitted the model using the training set (June 2008 to December 2017, 115 months) and evaluated the forecasting accuracy of the model using the test set (January 2018 to December 2018, 12 months).

Methods

BART

The Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART)20 is a ‘sum-of-trees’ model in which each tree is constrained by the prior and the model expression is as follows.

where \(T_{i}\) represents a binary regression tree, including splitting rules and a set of terminal nodes, \({\varvec{M}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) denotes the value of the parameter associated with the terminal node of \(T_{i}\). Each tree fits residuals that are not explained by the rest of the trees, so the final predicted value is the sum of the predicted values of all the trees.

By assuming that each tree, the terminal nodes of each tree and \(\sigma_{e}^{2}\) are independent, it is possible to set the priors for \(p\left( {T_{i} } \right)\), \(p\left( {M_{i} |T_{i} } \right)\) and \(p\left( {\sigma_{e} } \right)\). For \(p\left( {T_{i} } \right)\), it consists of the depth of the tree, the splitting rules and the splitting values. In order to make the probability of the terminal node higher as the tree depth gets progressively larger, the authors assume that the probability is \(\alpha \left( {1 + d} \right)^{ - \beta }\). For splitting rules, the uniform prior of the available variables is used, and for splitting values, the uniform prior of the discrete set of available splitting values is used. The prior for the terminal node parameters \(p\left( {M_{ij} |T_{i} } \right)\) is assigned a normal distribution. For \(p\left( {\sigma_{e} } \right)\), the inverse chi-square distribution of the conjugate prior is given.

Therefore, based on the observed data Y, the posterior distribution is generated. The point estimates are generated from the mean of samples that are sampled by the back-fitting MCMC algorithm, and interval estimates are obtained from the percentile of these samples.

ARIMA

The Auto-regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model is the classic model for time series forecasting24. It combines autoregressive and moving average terms. When the time series contains seasonal features, the Seasonal Auto-regressive Integrated Moving Average model is required for forecasting. The models without and with seasonal features can be expressed respectively as ARIMA (p, d, q) and ARIMA (p, d, q) × (P, D, Q)S, where p, q, P and Q denote the order of auto-regression and moving average, the order of seasonal auto-regression and moving average, respectively. d and D denote the number of non-seasonal and seasonal differences, and s denotes the length of the seasonal period.

Before constructing the ARIMA model, we performed an evaluation of stationarity using the ADF test, and performed a difference transformation when non-stationarity was detected. For series exhibiting significant heteroskedasticity (as determined by residual diagnostics), we performed variance stabilization using the Box-Cox transformation. After model fitting, we performed the Ljung-Box test for residual autocorrelation to verify that the model met the necessary assumptions. In order to maintain comparability with the BART model, we employ a rolling prediction strategy, i.e., each step of the prediction uses a fixed window of historical data to generate predictions for the test set on a rolling basis.

We constructed the ARIMA and BART models for the regions. For ARIMA model, the optimal model was selected based on the Bayesian Information Criterion. The smaller of the BIC values indicates that the model fits the data better. For the BART model, we first applied a Box-Cox transformation to normalize the count data and incorporated 12-month lagged terms as model inputs to explicitly account for seasonal patterns. The model employed the recommended default hyperparameters (\(\alpha\) = 0.95, \(\beta\) = 2) and followed by a comprehensive tuning via grid search to optimize: (i) Number of trees (ntree:50–500); (ii) Branching factor (k:1–4); (iii) Burn-in iterations (nskip:50–300); (iv) Posterior draws (ndpost:300–1200). All statistical analysis were completed in R (v4.1.2), employing the forecast package for ARIMA and the BART package for BART implementation.

Evaluation metrics

For the accuracy of point forecasting, we used root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) to evaluate the performance of the models. The model with smaller RMSE and MAPE and larger PCC has better performance.

where \(y_{i}\) is the actual value, \(y_{i}^{*}\) is the forecast value and \(\overline{y}\) is the mean value.

For interval forecasting, Prediction Interval Coverage Probability (PICP) reflects the probability that the actual value falls in the upper and lower limits of the prediction interval at a certain confidence level \(\alpha\). The closer the PICP is to 1, the more reliable the prediction is25. Prediction Interval Normalized Average Width (PINAW) reflects the average width between the upper and lower limits of the prediction interval. When the PICP values are the same, a smaller PINAW indicates that the model has better predictive performance. Since PICP and PINAW reflect only unilateral evaluation, they cannot reflect the comprehensive performance of interval prediction26. Therefore, we used the coverage width-based criterion (CWC) to compare the performance of the models in interval prediction. The smaller the CWC value, the better the model performs.

\(\left\{ {\left[ {\zeta_{t} ,\mu_{t} } \right]} \right\}_{t \in \varepsilon }\) denotes the set of samples of the forecasting interval, \(\zeta_{t}\) and \(\mu_{t}\) represent the lower and upper bounds of the prediction interval, respectively. \(\varepsilon\) is the set of time scales of the forecasting interval. \(R\) represents the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the observed values in the \(\varepsilon\). \(\lambda\) refers to the penalty parameter, which is taken as 1 in this study.

Results

Descriptive analysis

During the study period, 112,900, 3,180,399, 899,174, 137,851, 1,054,432, 285,960 and 672,533 cases of HFMD were reported in Gansu, Guangdong, Henan, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Shanxi and Sichuan, respectively. Figure 1 represents the monthly number of HFMD cases in these areas from 2008 to 2018. There were the most cases of HFMD reported in Guangdong, followed by Shandong, and the least number of cases reported in Gansu. The largest outbreaks in Heilongjiang and Henan occurred in 2009. The largest outbreak in Shandong was in 2010. The largest outbreak in Gansu was in 2012. The largest outbreaks in Shanxi and Guangdong were in 2014. The largest outbreak in Sichuan was in 2018. There was an annual peak (from April to July) in Heilongjiang, Gansu, Shanxi, Henan and Shandong. In Guangdong and Sichuan, there were two peaks annually, the first from April to July and the second from October to December. The detailed data description of the HFMD by region is shown in Table S1.

Model performance

Point forecast performance

Table 1 summarizes the performance of ARIMA and BART model in forecasting the number of HFMD cases in each region from January 2018 to December 2018, where the bold marks are the optimal metric values.

In this study, in terms of MAPE, the BART performed best in all provinces, indicating that BART has a significant advantage over ARIMA model. In terms of RMSE, the BART had the smallest values in six provinces (Gansu, Guangdong, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Shanxi and Sichuan), and ARIMA performed best in Henan. In terms of PCC, the BART model achieved higher correlation between predicted and actual values in all provinces compared to ARIMA model. To better understand the performance of the models, we ranked the models according to RMSE, MAPE and PCC. In addition, we calculated the average ranking of the models. The average rankings of BART model for RMSE, MAPE and PCC were 4124.997, 42.463 and 0.921, respectively, which outperformed the average rankings of ARIMA: 4930.210, 160.030 and 0.834 (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, the lines between the metric of BART and ARIMA models in each province were almost in a downward trend.

To visualize the number of HFMD cases predicted by the model compared with the actual number of cases, we plotted the predicted values as well as the actual cases in all provinces from January 2018 to December 2018 (Fig. 3). The ARIMA model and the BART model predicted the trend well in most provinces (except Sichuan). In Henan, both models underestimated the peak. The predicted values of the BART model in Gansu, Heilongjiang, Shandong and Shanxi were closer to the actual number of cases. In summary, the BART machine learning model that combines Bayesian and decision trees outperformed the traditional ARIMA model.

Interval forecast performance

In terms of CWC, the BART model has the lowest values in all provinces, indicating its ability to achieve a high performance that takes into account interval coverage and width.

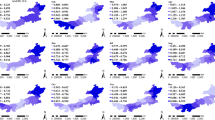

To visualize the interval prediction performance of the models, we plotted the predicted values of the models and their prediction intervals at the 95% confidence level, as well as the corresponding actual values (Fig. 4). In general, the ARIMA model had a wider prediction interval. In contrast, the BART model obtained narrower prediction intervals by sampling. The actual values were around the BART model prediction curve, with smaller prediction intervals, except for Sichuan, while the ARIMA model did not cover all actual values in Gansu, Henan and Shanxi. In Sichuan, the BART model had a higher coverage of prediction intervals; moreover, the upper limit of the prediction interval for the BART model was closer to the actual value.

To demonstrate the predictive ability of the BART model, we also constructed the random forest, XGBost, and static ARIMA models. The results of the comparison of the five forecasting models (ARIMA, BART, XGBoost, Random Forest, and ARIMA_static) are shown in Table S2. ARIMA_static indicates that constructing an ARIMA model directly predicts all values in the test set. In terms of point forecasting accuracy, BART model consistently outperformed other models across multiple provinces, reducing RMSE compared to ARIMA in six out of seven provinces. XGBoost showed competitive performance in several regions, notably in Gansu (RMSE: 427.4) and Shandong (RMSE: 1701.3), while Random Forest ranked first in Guangdong (RMSE: 10,190.4). The traditional ARIMA_static model exhibited the poorest performance, with substantially higher error metrics across all provinces, particularly in Heilongjiang (MAPE: 250.3) and Guangdong (MAPE: 267.1).

For interval forecasting performance, the BART model demonstrated clear superiority with consistently minimal CWC values, reflecting its optimal balance between prediction interval reliability (PICP) and precision (PINAW). While XGBoost exhibited competent interval forecasting capability in certain regions, its coverage reliability showed greater variability (PICP: 0.166–0.666). The Random Forest model proved less reliable for interval predictions (PICP: 0.083–0.583). Notably, the ARIMA_static model generated excessively wide prediction intervals (maximum PINAW: 3.111), rendering them practically ineffective despite achieving nominally high coverage rates.

The comprehensive assessment reveals a clear performance hierarchy: BART consistently outperformed other models, followed by XGBoost, then Random Forest, with traditional time-series models (ARIMA and ARIMA_static) showing the weakest performance. This pattern held across both point and interval forecasting metrics, with machine learning approaches demonstrating particular advantages in handling complex disease patterns. The results suggest that ensemble methods combining Bayesian approaches with decision trees (BART) offer the most robust solution for HFMD forecasting, balancing predictive accuracy with practical decision-support capabilities that address real-world public health needs.

Discussion

In this study, we built Bayesian additive regression tree models based on seven regions in mainland China to accurately predict monthly HFMD cases in 2018 and quantify the prediction uncertainty using prediction intervals. Overall, the BART model achieved an improvement in prediction performance compared with the ARIMA model. The mean MAPE value of BART model across the seven regions was reduced by 73.465%, the mean RMSE value was reduced by 16.332%, and the mean PCC value was improved by 10.432%. In addition, in most areas, the BART model covered the actual number of HFMD cases by a narrow prediction interval.

We found that the BART model improved the prediction accuracy compared with the traditional time series model (ARIMA). The result was consistent with previous studies on the forecasting of other infectious diseases27,28,29,30, which showed that the machine learning method of decision trees outperformed ARIMA. There may be two main reasons: first, the tree-structured model is more suitable for dealing with nonlinear data; second, the BART is an ensemble learning method that weakens each tree by boosting, leading to good global performance. For example, in Gansu and Heilongjiang provinces, the predicted curves of the BART model were obviously closer to the actual curves. However, the predicted curves of the BART and ARIMA models in Sichuan differed from the actual curves, which may be due to the sharp increase of the number of cases in 2018.

The probabilistic forecasting of infectious diseases is more important than point forecasting31,32, providing forecast uncertainty to help public health workers to respond to epidemics better. We used the BART probability model to sample 200 or 500 or 1000 times from the posterior distribution to calculate the prediction interval at the 95% confidence level for the study area. The interval plot showed that the actual values of the vast majority of the regions were within the prediction interval. Meanwhile, the CWC metrics which consider the probability of covering the actual values and the width of the interval showed that the BART model obtains smaller values in all regions, i.e., it is able to cover all real values by a narrower prediction interval. This suggests that the BART model is suitable for constructing early warning systems that can predict outbreaks 1–12 months in advance using its accurate point predictions and reliable uncertainty intervals; it also allows for resource optimization, with narrower prediction intervals, which allows for more efficient allocation of vaccines and medical supplies.

Because the MAPE has the advantage of scale-independence and interpretability, it can be used as a measure of predictive accuracy33. The MAPE values of this study model in the study area were slightly different from previous studies in mainland China. For example, Liu et al. showed a MAPE of 15.982% for the prediction of the monthly HFMD incidences in Sichuan Province from 2010 to 201434. Du et al. predicted the weekly HFMD incidence in Guangdong Province with a MAPE of 122.544%35. While the MAPE of our BART models in Sichuan and Guangdong provinces were 29.581% and 74.818%. These may be caused by different time periods or time resolutions of the data.

To date, there are limited studies that provide uncertainty intervals for HFMD prediction. Although there are some studies using ARIMA models that provide prediction intervals34,36,37,38, these studies focused on accuracy and not on the uncertainty of the forecasts. To our knowledge, this study was the first to consider the uncertainty of HFMD prediction and used the BART model for probabilistic prediction. In addition, our study used the number of HFMD cases of seven regions in mainland China to objectively validate the generalization ability of the BART probabilistic model. The current studies exploring methods to improve the accuracy of HFMD forecasting are almost based on one city or province. For example, Xie et al. verified that the forecasting accuracy of Prophet was higher compared to ARIMA in Hubei province39. Liu et al. demonstrated the superiority of BP neural networks over ARIMA based on Jiangsu province40. Wang et al. demonstrated that deep learning methods outperformed vector autoregression based on Beijing41.

Some limitations of our study should also be acknowledged. First, the performance of the BART model is limited when there is a sharp increase in infectious diseases. This is because the prior assignment of BART to the leaf parameters is normally distributed, whereas in practice the number of infectious disease cases is shown to follow a negative binomial distribution. Second, meteorological conditions have been shown to be associated with the spread of HFMD. In the future, we need to collect time series of HFMD in finer time units (day/week) to investigate the predictive performance of BART using meteorological variables as input features. In addition, we will also explore the application of the BART model for other infectious disease predictions.

Conclusions

In this study, we built Bayesian additive regression tree probability models to predict the trend of HFMD cases and provided prediction uncertainty by using prediction intervals. Meanwhile, we compared it with the ARIMA model in seven regions of mainland China. The results demonstrated that the BART model can accurately predict the trend of HFMD and also provide reliable prediction intervals. This study helps public health departments to carry out reliable intervention decisions based on the prediction curves and prediction intervals at 95% confidence level.

Data availability

The data was obtained from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention through the Public Health Sciences Data Center (https://www.phsciencedata.cn/).

References

Xing, W. et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008–12: An epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 14, 308–318 (2014).

De, W. et al. A large outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by EV71 and CAV16 in Guangdong, China, 2009. Arch. Virol. 156, 945–953 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Epidemiological analysis, detection, and comparison of space-time patterns of Beijing hand-foot-mouth disease (2008–2012). PLoS ONE 9, e92745 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. An emerging recombinant human enterovirus 71 responsible for the 2008 outbreak of hand foot and mouth disease in Fuyang city of China. Virol. J. 7, 94 (2010).

Mao, L.-X. et al. Epidemiology of hand, foot, and mouth disease and genotype characterization of enterovirus 71 in Jiangsu, China. J. Clin. Virol. 49, 100–104 (2010).

Koh, W. M., Badaruddin, H., La, H., Chen, M.I.-C. & Cook, A. R. Severity and burden of hand, foot and mouth disease in Asia: A modelling study. BMJ Glob Health 3, 000442 (2018).

Ji, T. et al. Surveillance, epidemiology, and pathogen spectrum of hand, foot, and mouth disease in mainland of China from 2008 to 2017. Biosaf. Health 1, 32–40 (2019).

Aswathyraj, S., Arunkumar, G., Alidjinou, E. K. & Hober, D. Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD): Emerging epidemiology and the need for a vaccine strategy. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berl). 205, 397–407 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. Cost-effectiveness of a national enterovirus 71 vaccination program in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005899 (2017).

Fang, C.-Y. & Liu, C.-C. Recent development of enterovirus A vaccine candidates for the prevention of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines 17, 819–831 (2018).

Hong, J. et al. Changing epidemiology of hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2013–2019: A population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 20, 100370 (2022).

Man, H., Huang, H., Qin, Z. & Li, Z. Analysis of a SARIMA-XGBoost model for hand, foot, and mouth disease in Xinjiang, China. Epidemiol. Infect. 151, e200 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. Epidemiological characteristics and prediction model construction of hand, foot and mouth disease in Quzhou city, China, 2005–2023. Front. Public Health 12, 1474855 (2024).

Lonlab, P., Anupong, S., Jainonthee, C. & Chadsuthi, S. Seasonal and meteorological drivers of hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks using data-driven machine learning models. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 10, 48 (2025).

Yoshida, K., Fujimoto, T., Muramatsu, M. & Shimizu, H. Prediction of hand, foot, and mouth disease epidemics in Japan using a long short-term memory approach. PLoS ONE 17, e0271820 (2022).

Wan, Y., Song, P., Liu, J., Xu, X. & Lei, X. A hybrid model for hand-foot-mouth disease prediction based on ARIMA-EEMD-LSTM. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 879 (2023).

Zhu, H. et al. Study of the influence of meteorological factors on HFMD and prediction based on the LSTM algorithm in Fuzhou, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 299 (2023).

Etemadi, S. & Khashei, M. Accuracy versus reliability-based modelling approaches for medical decision making. Comput. Biol. Med. 141, 105138 (2022).

Shrestha, D. L. & Solomatine, D. P. Machine learning approaches for estimation of prediction interval for the model output. Neural Netw. 19, 225–235 (2006).

Chipman, H. A., George, E. I. & McCulloch, R. E. BART: Bayesian additive regression trees. Ann. Appl. Stat. 4, 266–298 (2010).

Zhang, T., Geng, G., Liu, Y. & Chang, H. H. Application of Bayesian additive regression trees for estimating daily concentrations of PM2.5 components. Atmosphere 11, 1233 (2020).

Waldmann, P. Genome-wide prediction using Bayesian additive regression trees. Genet. Sel. Evol. GSE 48, 42 (2016).

Wu, W., Tang, X., Lv, J., Yang, C. & Liu, H. Potential of Bayesian additive regression trees for predicting daily global and diffuse solar radiation in arid and humid areas. Renew. Energy 177, 148–163 (2021).

Box GEP. Time Series Analysis.

Xiao, L., Li, M. & Zhang, S. Short-term power load interval forecasting based on nonparametric Bootstrap errors sampling. Energy Rep. 8, 6672–6686 (2022).

Niu, D., Sun, L., Yu, M. & Wang, K. Point and interval forecasting of ultra-short-term wind power based on a data-driven method and hybrid deep learning model. Energy 254, 124384 (2022).

Zhang, J. & Nawata, K. A comparative study on predicting influenza outbreaks. Biosci. Trends 11, 533–541 (2017).

Kane, M. J., Price, N., Scotch, M. & Rabinowitz, P. Comparison of ARIMA and random forest time series models for prediction of avian influenza H5N1 outbreaks. BMC Bioinf. 15, 276 (2014).

Patil, S. & Pandya, S. Forecasting dengue hotspots associated with variation in meteorological parameters using regression and time series models. Front. Public Health 9, 798034 (2021).

Fang, X. et al. Forecasting incidence of infectious diarrhea using random forest in Jiangsu province, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 222 (2020).

Gneiting T, Katzfuss M. Probabilistic Forecasting. In: Fienberg SE (eds) Annual Review of Statistics and its Application, Vol 1. 2014. p. 125–51.

Held, L., Meyer, S. & Bracher, J. Probabilistic forecasting in infectious disease epidemiology: The 13th Armitage lecture. Stat Med. 36, 3443–3460 (2017).

Kim, S. & Kim, H. A new metric of absolute percentage error for intermittent demand forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 32, 669–679 (2016).

Liu, L., Luan, R. S., Yin, F., Zhu, X. P. & Lü, Q. Predicting the incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease in Sichuan province, China using the ARIMA model. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 144–151 (2016).

Du, Z. et al. Predicting the hand, foot, and mouth disease incidence using search engine query data and climate variables: An ecological study in Guangdong, China. BMJ Open 7, e016263 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Development and evaluation of a deep learning approach for modeling seasonality and trends in hand-foot-mouth disease incidence in mainland China. Sci. Rep. 9, 8046 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Temporal and long-term trend analysis of class C notifiable diseases in China from 2009 to 2014. BMJ Open 6, e011038 (2016).

Song, Y. et al. Time series analyses of hand, foot and mouth disease integrating weather variables. PLoS ONE 10, e0117296 (2015).

Xie, C. et al. Trend analysis and forecast of daily reported incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease in Hubei, China by Prophet model. Sci. Rep. 11, 1445 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Forecasting incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease using BP neural networks in Jiangsu province, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 828 (2019).

Wang, Y., Cao, Z., Zeng, D., Wang, X. & Wang, Q. Using deep learning to predict the hand-foot-and-mouth disease of enterovirus A71 subtype in Beijing from 2011 to 2018. Sci. Rep. 10, 12201 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872713 to FY); Science and Technology Program of Henan, China (242102310267 to YS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoran Geng and Fei Yin designed the study, Xiaoran Geng drafted the manuscript, Yue Ou and Yuan Shi prepared figures; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China School of Public Health, Sichuan University. All HFMD surveillance data in this study were obtained from the Chinese Disease Prevention and Control Information System. No human participants were actually involved in this study. Therefore, this study did not require informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, X., Shi, Y., Ou, Y. et al. Probabilistic forecasting of hand, foot and mouth disease in Mainland China using Bayesian additive regression tree model. Sci Rep 15, 33745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98954-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98954-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Residual bayesian attention networks for uncertainty quantification in regression tasks

Scientific Reports (2025)