Abstract

Conventional compensation approaches for gear error (e.g., Monte Carlo simulations) have shown efficacy in uniform meshing scenarios, however, two drawbacks limit further applications: (1) high computationally cost and low efficiency in practical implementation; (2) inadequate adaptability to complex non-uniform meshing dynamics. Addressing these issues, this work proposes a Data-Augmentation Long Short-Term Memory (DA-LSTM) model to achieve high-precision manufacturing (GB5-level, GB/T 10095 − 2008 Grade 5) of gears machined through shaping processes. The developed DA-LSTM framework combines LSTM architecture with adaptive Data-Augmentation strategies, enabling efficient prediction and compensation of machining errors under non-uniform engagement conditions. By optimizing tools trajectories and process parameters, experimental results show that the proposed method achieves GB5-level machining accuracy while achieving a 40% reduction in computational cost relative to baseline methods. Notably, the framework maintains superior prediction accuracy across varying meshing conditions, effectively bridging the research gap in adaptive error compensation for complex gear shaping operations. The presented method provides a novel technical pathway for high-precision gear manufacturing in non-ideal meshing environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As critical transmission elements in heavy-duty machinery, gears manufactured via shaping processes exhibit irreplaceable advantages-particularly for large-scale, asymmetric, and non-circular gear production-where conventional shaping machines fail to meet GB5-level precision requirements. Recent advancements in profile grinding technology suggest that analytical methods based on envelope theory can significantly improve machining efficiency and precision (time reduced by 15 times compared to numerical methods)1, yet such innovations remain underutilized in gear shaping applications. In the processing of short receding groove gears, precision control relies only on the gear shaping processing. With the continuous improvement in gear precision requirements for precision transmission equipment, the key precision indices of precision gears, such as total cumulative pitch deviation (Fp) and radial runout tolerance (Fr), must reach the GB5-level or above. However, owing to the limitations of the diameter specifications and processing principles, there is currently no precision gear grinding machine to meet the processing requirements of such gears. This gap contrasts sharply with progress in other machining fields; for instance, micro-textured surface fabrication via milling has achieved sub-micron precision through advanced tools path planning and vibration-assisted techniques2. Conventional gear shaping processing can only achieve a GB6-GB7 level, and it is difficult to meet the processing requirements of high-precision gears. Notably, the analytical forward- and backward-calculation processes proposed in1 demonstrate maximum geometric errors below 0.18 mm for grinding wheels, indicating potential for integration with shaping systems to enhance accuracy. In addition, limited by the machining accuracy of the machine parts, assembly accuracy, machine control accuracy, and stability, the development of high-precision gear shaping machines faces many technical challenges. Cross-disciplinary insights from micro-texturing research2, which systematically addresses factors like tools geometry and kinematic control, could inform solutions to these challenges.

In terms of gear error compensation, Donmez and Kahraman3 investigated the effects of tooth indexing error and gear eccentricity on gear rattle, and a new no-rattle criterion including the eccentricity parameters is proposed. Zhang et al.4 deduced the similarity relationship between gear systems under machining error conditions and proposed two scaling model correction methods for machining error distortion. Zhou et al.5 proposed a crack initiation life model for standard and error gears based on tooth stress history and the critical plane method of non-proportional loading, and investigated the effects of center error and angular misalignment on the crack initiation life of herringbone gears. Vivet et al.6 conducted tooth contact analysis on spiral bevel gears to simulate the effect of gear alignment errors. In addition, some studies have revealed the effect of machining accuracy on gear transmission performance. Bonori and Pellicano7 analyzed the effect of profile error and its variation on gear vibration by considering the profile error as a random variable, whereas Driot and Perret-Liaudet8 predicted changes in the dynamic behavior of gear systems caused by tolerance. Liu et al.9 established predictive models for transmission error ranges of spur gears at different accuracy levels, whereas Guo and Fang10 investigated the effects of random manufacturing errors on the dynamic performance of gear systems through statistical analysis.

In terms of simulations, Zhang and Guo11 analyzed the trimming uncertainty of helical planetary gears based on the response surface method and Monte Carlo simulation. Hu et al.12investigated the effect of random errors on the dynamic load distribution behavior of a closed differential planetary transmission system using the Monte Carlo method. Liu et al.13 established a probability distribution model for the variation in gear meshing stiffness with random tooth pitting and verified the validity of the model using the Monte Carlo method. Wei et al.14studied the dynamic response behavior of gear trains with uncertain parameters based on the Chebyshev interval method. However, although Monte Carlo methods are widely used in the aforementioned studies, their limitations of high computational volume and low efficiency remain difficult to ignore. In contrast, DA-LSTM model based on the Data-Augmentation theory proposed in this study significantly improves computational efficiency while maintaining prediction accuracy.

To meet the challenges of error compensation and accuracy optimization in high-precision gear machining, this study proposes a gear error prediction model based on DA-LSTM to optimize the machining trajectory and parameters during gear shaping. In addition, this paper also explores the optimization method of gear shaping accuracy under non-uniform meshing conditions, and verifies the feasibility and effectiveness of the method through experiments. This study not only proposes an innovative technical path for high-precision gear machining, but also establishers a theoretical foundation and practical support for enhancing the accuracy of CNC gear shaping machines and advancing error control methodologies in precision machining application.

Gear error mapping

There exists an explicit functional mapping relationship between the geometric errors of gear workpieces—including profile deviation, total cumulative pitch deviation, and radial run-out tolerance of the gear ring—and the motion errors of machine tools axes (e.g., radial feed axis, workpiece rotation axis, and tools rotation axis) during the gear shaping process, as illustrated in Fig. 1. By establishing such mapping models, the quantitative influence of individual axis error components (e.g., Ex, Ec, Ey) on gear machining accuracy can be systematically evaluated. Furthermore, the gear errors are inversely decoupled into corresponding motion axes based on the mapping relationships. This enables comprehensive error compensation through dynamic adjustments of tools radial feed and optimization of rotational speeds, thereby significantly enhancing shaping precision.

Mathematical modeling of cumulative total deviation mapping of gear pitch

The total cumulative total tooth pitch deviation (Fp) represents the algebraic difference between the actual arc length and the theoretical counterpart within any k tooth pitch on the cylindrical gear indexing circle. Its generation is closely related to the motion errors of the tools radial feed axis, workpiece rotation axis and tools rotation axis. As shown in the Fig. 2 (a), it illustrates the process of shaping. Subfigures (b-d) illustrate the influence of motion errors from the tools radial feed axis, workpiece rotation axis, and tools rotation axis on gear profile deviations. Where the direction of motion of the workpiece rotation axis is in the direction of \(\:{\omega}_{c}\) and the direction of motion of the tools rotation axis is in the direction of \(\:{\omega}_{y}\). Next, the effects of these three axes of motion on the gear profile error are analyzed, and the corresponding mathematical model will be derived.

As shown in Fig. 2 (b). The tooth profile deviation of the gear is caused by the motion error of each axis of the gear shaping machine on the gear meshing line, then the motion error of the radial feed axis of the tools on the tooth profile deviation is the component in the direction of its meshing\(\:{{E}_{x}}^{{\prime\:}}\):

In Fig. 2 (c)\(\:,\) the radian deviation \(\:{{E}_{c}}^{{\prime}}\:\)induced by motion error \(\:{E}_{c}\:\)of the workpiece rotary axis could be expressed by,

Further, the tooth profile deviation \(\:{{E}_{c}}^{{\prime\prime\:}}\)caused by motion error of the rotating workpiece axis is determined by,

In Fig. 2 (d), similar to the workpiece rotary axis, the angular deviation \(\:{E}_{y}\) is the motion error of the tools rotary axis, and the resultant radian deviation \(\:{{E}_{y}}^{{\prime\:}}\)is related to the angular deviation \(\:{E}_{y}\) by,

The effect of the motion error of the rotary axis on the tooth profile deviation is \(\:{{E}_{y}}^{{\prime}}\), a component in the direction of the meshing line \(\:{{E}_{y}}^{{\prime\prime\:}}\). I.e.:

Based on the above error components of each axis in the direction of the gear meshing line, the mathematical model of the tooth profile deviation \(\:{F}_{a}\) is obtained as:

Eq: \(\:{K}_{ax},{K}_{ac},{K}_{ay}\) takes the value of 1 or − 1, determined by the tools, workpiece machining parameters and machining process method.

Mathematical modeling of radial runout tolerance mapping for gear rings

The radial runout tolerance \(\:{F}_{r}\) is the deviation between the axial position of the gear ring and the ideal position, and the total cumulative pitch deviation (Fp) of the tooth pitch generates the similarity factors, which are mainly related to the tools radial feed axis, workpiece rotation axis, and tools rotation axis of the tracking movement error.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the motion error of the tools radial feed axis significantly influences the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring. This effect is particularly evident when the tools is fully engaged with the gear workpiece, where a discrepancy arises between the theoretical and actual distances along the centerline connecting the tools and workpiece centers.

As shown in Fig. 2 (c), the influence of the workpiece rotating axis on the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring is \(\:{E}_{c}\:\), which is converted into radian \(\:{{E}_{c}}^{{\prime\:}}\) and calculated using the following formula:

Its radial component at the gear meshing point is:

Similarly, Fig. 2 (d) shows that the effect of the tools rotation axis on the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring is \(\:{E}_{y}\), which is converted into radians \(\:{{E}_{y}}^{{\prime\:}}\), calculated as:

Its radial component at the gear meshing point is:

From the above equation, the mathematical model of the radial runout tolerance \(\:{F}_{r}\) of the gear ring can be determined by:

Through the established mathematical model of gear profile form deviation(Fa), total cumulative pitch deviation, and radial runout tolerance(Fr), the mapping relationship between the total cumulative pitch deviation(Fp) and radial runout tolerance(Fr) and the motion error of each motion axis of the gear shaping machine can be clarified. Among them, the motion error of the radial feed axis of the tools mainly leads to the vertical deviation of the gear indexing circle (Eq. 1), which directly affects the profile accuracy of the gear (\(\:{F}_{a}\)). The kinematic error of the workpiece rotary axis is transformed into radial and tangential errors through the pressure angle α (Eq. 3), which has a significant effect on the radial runout tolerance (\(\:{F}_{r}\)). The kinematic error of the tools rotary axis also affects the radial runout and profile accuracy of the gear through the pressure angle α (Eq. 5), but to a slightly lesser extent than the workpiece rotary axis.

Gear error prediction

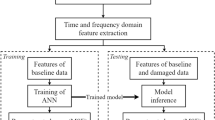

This study establishes a comprehensive time-series dataset using gear workpiece error data obtained from gear shaping processes, encompassing error profiles manufactured by the same shaping machine across diverse temporal intervals. To enhance model predictive performance, we propose a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based gear error prediction model integrated with Data-Augmentation theory. The gear error data undergoes preprocessing through advanced Data-Augmentation algorithms to extract more profound feature representations, which are subsequently fed into the LSTM architecture for predictive analysis of gear machining errors. Following preprocessing and augmentation procedures, the total cumulative pitch deviation (Fp) and radial runout tolerance (Fr) of the gear ring are transformed into a two-dimensional array containing 30,000 discrete data points. A subset of these time-series parameters is strategically selected for data enhancement, with the augmented samples being partitioned into training and testing datasets for model development and validation.

The predictive capability of the DA-LSTM model is systematically demonstrated through comprehensive graphical representations: Figures 4 and 5 respectively demonstrate the model’s predictive results of the total cumulative pitch deviation (Fp) for the left and right tooth flanks, while Fig. 6 illustrates the prediction outcomes of the radial runout tolerance (Fr). To quantitatively assess the model’s predictive accuracy, we employed two robust evaluation metrics: root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE), with the corresponding numerical results meticulously documented in Table 1.

Comparative analysis between DA-LSTM and Monte Carlo simulation approaches, as summarized in Table 2, reveals that the proposed DA-LSTM architecture achieves superior performance metrics: a statistically significant 46.5% reduction in RMSE (p < 0.01, t-test), a 75% decrease in computational time, and a 7.3% improvement in prediction accuracy compared to conventional methods.

Gear shaping optimization

A systematic theoretical framework was established through deriving the mapping relationships between individual gear shaper axis motion errors and two critical gear accuracy parameters-total cumulative pitch deviation and gear ring radial runout tolerance-followed by performing error decoupling across all motion axes, thereby constructing a foundational model for precision compensation in gear shaping processes. Based on the DA-LSTM gear error prediction model, the cumulative total tooth pitch deviation and gear ring radial runout tolerance of the gear to be machined can be predicted, and these two error indicators can be further decoupled to the radial feed axis of the tools, the rotary axis of the tools, and the rotary axis of the workpiece, so as to provide a theoretical basis and technical support for the realization of error compensation.

Decoupling of cumulative total deviation of tooth pitch

The cumulative total tooth pitch deviation is mapped on the radial feed axis of the tools as its component \(\:{F}_{Px}\) perpendicular to the tangent line of the gear index circle during the gear shaping process, which is calculated according to Fig. 2 (d) and Eq. (7):

According to Fig. 2 (d) and Eq. (5), the error component \(\:{F}_{Py}\) of the total cumulative pitch deviation on the tools rotation axis is:

Eq: \(\:{E}_{y}\) is the angle, according to the angle calculation formula:

It is known that the angular velocity deviation of the tools rotation is:

Similarly, the error component \(\:{F}_{pc}\) of the total cumulative pitch deviation on the rotational axis of the workpiece can be expressed as.

If \(\:{F}_{pc}\)>0, the feed in the absolute value of \(\:{F}_{pc}\) in the radial feed axis of the tool decreases; if \(\:{F}_{pc}\)<0, the feed in the absolute value of \(\:{F}_{pc}\) in the radial feed axis of the tools increases; if \(\:{F}_{pc}\)=0, the feed in the radial feed axis of the tools remains unchanged.

The angular velocity deviation of the workpiece is known from the angular calculation formula:

To facilitate the realization of error compensation, the angular velocity of the workpiece rotary axis was fixed, process optimization was performed by adjusting the angular velocity of the tools rotary axis, and the angular velocity \(\:\omega\:\) of the tools was calculated as follows:

If \(\:\omega\:\)>0, the angular velocity of the absolute value of \(\:\omega\:\) decreases in the tools rotation axis; if \(\:\omega\:\)<0, the angular velocity of the absolute value of \(\:\omega\:\) increases in the tools rotation axis; and if \(\:\omega\:\)=0, the angular velocity of the tools rotation axis remains unchanged.

Therefore, it is possible to realize the motion error compensation of the tools radial feed axis for the total cumulative pitch deviation by adding \(\:{F}_{Px}\) to the motion parameter of the tools radial feed axis, and the motion error compensation of the tools rotary axis and workpiece rotary axis for the total cumulative pitch deviation by increasing \(\:\omega\:\) to the rotational angular velocity of the tools rotary axis.

Tolerance decoupling of radial runout of gear ring

According to Fig. 3 and Eq. (7), it can be seen that the mapping of the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring on the radial feed axis of the tools is the interpolation of the theoretical center distance between the tools and workpiece in the gear machining process and the actual center distance, which is calculated as follows.

Where \(\:{E}_{x}\) is the difference between the theoretical and actual center distances between the tools and workpiece during the shaping process.

According to 3 and Eq. (5), the component \(\:{F}_{ry}\) of the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring on the rotating axis of the tools is.

If \(\:{F}_{ry}\)>0, the feed in the absolute value of \(\:{F}_{ry}\) in the radial feed axis of the tools; if \(\:{F}_{ry}\)<0, the feed in the absolute value of \(\:{F}_{ry}\) in the radial feed axis of the tools is increased; if \(\:{F}_{ry}\)=0, the feed in the radial feed axis of the tools remains unchanged.

where \(\:{E}_{y}\) is the angle, according to the angle calculation formula:

It is known that the angular velocity deviation of the tools rotation is:

Similarly, the angular velocity deviation on the rotational axis of the workpiece is:

Similarly, in order to facilitate the realization of error compensation, the angular velocity of the workpiece rotary axis is fixed, and the process optimization is carried out by adjusting the angular velocity of the tools rotary axis, and the tools angular velocity \(\:\omega\:\) is calculated as:

If \(\:\omega\:\) >0, the angular velocity of the absolute value of \(\:\omega\:\) decreases in the tools rotation axis; if \(\:\omega\:\) <0, the angular velocity of the absolute value of \(\:\omega\:\) increases in the tools rotation axis; and if \(\:\omega\:\) =0, the angular velocity of the tools rotation axis remains unchanged.

Therefore, the motion error compensation of the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring in the direction of the tangent line of the vertical indexing circle can be realized by adding \(\:{F}_{rx}\) to the machining parameter of the tools radial feed axis. The motion error compensation of the joint motion of the tools rotary axis and workpiece rotary axis for the gear ring radial runout tolerance can be realized by increasing \(\:\omega\:\) the rotational angular velocity of the tools rotary axis.

Simulation analysis of non-uniform meshing shaping process

Based on the above error decoupling method, the total cumulative pitch deviation and the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring predicted by the DA-LSTM model were combined for error decoupling. Based on the decoupling results, the process parameters of the radial feed axis and rotary axis of the tools of the gear-inserting machine were further adjusted. Based on the principle of non-uniform meshing, a corresponding gear shaping accuracy optimization method was designed, and the effectiveness of the method was verified by a Vericut simulation. The simulation results for the machining process are shown in Fig. 7.

According to the simulation processing situation, it can be seen that the CNC program designed based on the optimization method of gear shaping accuracy of non-uniform meshing has no interference, collision, or other problems, the tools trajectory is correct, and the gear shaping machine error compensation code runs smoothly. The gear model after completing interpolation is shown in Fig. 8.

Experimentation and simulation

Non-uniform meshing interpolation machining experiment

The YK5132C CNC gear shaping machine was selected as the experimental verification platform, and a group of blanks was processed, as shown in Fig. 9. The experiment was completed without the application of a non-uniform meshing gear based on the optimization of the gear shaping accuracy method before conventional gear processing, the basic parameters of the processed gears for the number of teeth is 34, the module is 6 mm, and the pressure angle is 20°. Subsequently, the gear tooth profile data points are inspected using a high-precision measurement method to obtain the coordinate data of the gear tooth profile. Based on the gear error evaluation method of full coordinate inspection, the total cumulative pitch deviation and radial runout tolerance of the gear ring of the machined gear were calculated and analyzed. All calculation results were saved. Five gear workpieces were machined during the experiment; the results are shown in Fig. 10. The total cumulative pitch deviation on the left tooth flanks, cumulative total deviation of the tooth pitch on the right tooth flanks and radial runout tolerance of the gear ring for each workpiece are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5 respectively.

Based on the predicted gear error data, the error decoupling method proposed in this study was employed to decouple gear errors into three axes: the tools radial feed axis, tools rotary axis, and workpiece rotary axis, followed by adjustment of their process parameters. This approach established a non-uniform meshing-based optimization method for gear shaping accuracy, implemented Vericut-enabled simulation experiments, and ultimately performed interference-free test cutting of workpieces with validated program integrity. The experiment was carried out on a YK5132C CNC gear shaping machine to process a workpiece with non-uniform meshing gear shaping. The gear tooth profile data points were collected for error evaluation after machining was completed, as shown in Figs. 11 and 12.

The calculation results are presented in Table 6 using the gear error evaluation method to calculate the gear error.

Comparison of the error data of the gears machined by the gear-shaping machine before and after the process optimization is shown in Figs. 13, 14 and 15, and Table 7.

From Table 7, Figs. 13, 14, and 15, it is evident that the total cumulative pitch deviation for gears machined using the non-uniform meshing-based gear shaping accuracy optimization method is significantly reduced, with the optimized total cumulative pitch deviation being 0.02 mm (left flank) and 0.025 mm (right flank) and the radial runout tolerance being 0.017 mm for a gear with a module of 6 mm and 34 teeth, meeting the GB5 accuracy standard; furthermore, typical error ranges observed in practical machining include machine tools vibration (± 0.005 mm axial and ± 0.003° rotational), thermal drift (± 0.002 mm due to ambient temperature fluctuations (20–30 °C)), and material inhomogeneity (profile deviations up to 0.01 mm for hardened steel gears), which are inevitable in practical machining but can be effectively compensated for by the proposed optimization method, ensuring that the gear machining accuracy meets the GB5 accuracy standard.

Gear workpiece digital rolling inspection verification

Through the multi-body dynamics simulation software Automatic Dynamic Analysis of Mechanical Systems(ADAMS 2020, https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/adams/), a model of the gear transmission system is established to define key parameters such as mass, stiffness, and friction of the gears, specify the connection relationship and motion constraints between the master and follower wheels, and then simulate the dynamic behavior of the gear transmission system. Based on this model, a digital rolling inspection of the processed gears before and after the optimization of the gear shaping process was carried out.

1) Gear modeling.

The data points of the gear tooth profile processed before and after process optimization were detected using a coordinate measuring machine, and the detected data points were imported into AutoCAD for curve fitting, to obtain the profile graph of the gear. The results are shown in Fig. 16.

After obtaining the 2D engineering drawing of the gear, it was imported into the 3D software Solidworks 2022(https://www.solidworks.com/) to obtain the 3D model of the gear, as shown in Fig. 17.

2) Defining initial conditions.

After obtaining the gear model before and after the optimization of the machining process, a standard gear is established as the master wheel in the gear transmission process, driving the slave wheel before and after the optimization of the process to rotate, to obtain the change in the center distance of the master and slave wheels and the change in angular velocity in the gear transmission process. The specific parameters of the standard gears are presented in Table 8.

3) Digital roll check simulation setup.

The established gear transmission model was imported into the ADAMS simulation software. A rotating pair was added to the standard gear, and a coordinate system was added at the indexing circle and meshing intersection. An elastic force F pointing in the direction of the standard gear is applied to the non-standard gear to ensure that the gears mesh properly. Because the driven wheel moves in the opposite direction of the standard gear during meshing, an elastic force in the opposite direction must be applied to the non-standard gear to maintain the meshing state of the gears to counteract the contact force generated during the meshing of the gears. The specific elastic forces applied and contact forces generated are shown in Fig. 19.

The contact type of the model was set as solid-to-solid, normal force was set as collision force, object stiffness was 1.0E + 05 N/m, force index was 2.2, damping of 10 N·s/m, penetration depth was 0.1 mm, static coefficient of friction was 0.3, dynamic coefficient of friction was 0.1, net translational velocity was 100 mm/s, and frictional translational velocity was 1000 mm/s. The preload for the follower wheel was 40 N, and after the setup is complete, the rotational drive for the master wheel with \(\:{\omega}_{1}\) was 360°/s (2 pi/s), and the variation curve of the gear center distance h and the variation curve of the angular velocity \(\:{\omega}_{2}\) of the driven wheel were measured.

4) Analysis of results.

Completing the above preparatory work and simulation analysis, we can obtain the change curves of the center distance H between the main wheel and driven wheel and the angular velocity W of the driven wheel in the gear transmission process before not optimizing the gear shaping process as shown in Fig. 20 (a), (b). The change curves of the center distance h between the master and follower wheels and the angular velocity \(\:{\omega}_{2}\) of the follower wheel in the gearing process after optimizing the gear shaping process are shown in Fig. 20 (c), (d).

The specific values of the changes in the center distance of the master and slave wheels and the changes in the angular velocity of the slave wheel during the gearing process are listed in Table 9.

The Digital Rolling Inspection (DRI) technique enables quantitative evaluation of transmission errors in gear pairs during meshing processes. Based on DRI data, CNC gear shaping machines without compensation protocols exhibit significant kinematic instabilities, with center distance variations of up to 0.15 mm and abrupt angular velocity fluctuations reaching 200 deg/s. In contrast, systems enhanced with real-time compensation algorithms demonstrate superior transmission stability, limiting center distance deviations to ≤ 0.10 mm and angular velocity fluctuations to 120 deg/s. Primary error sources include sensor noise (± 0.005 mm) and thermal drift (± 0.003 mm), which can be mitigated through future integration of temperature compensation modules and enhanced sensor calibration protocols targeting < 0.001 mm resolution.

Conclude

This paper proposes an innovative method for gear shaping accuracy optimization and error compensation, based on the DA-LSTM model. An in-depth study is conducted to address gear machining under non-uniform meshing conditions. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

1) Effectiveness of DA-LSTM model in gear error prediction. By constructing a time-series dataset based on the gear workpiece error data and processing the gear error data using the data enhancement algorithm, the DA-LSTM gear error prediction model was successfully designed in this study. The experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves high accuracy in predicting the total cumulative pitch deviation and the radial runout tolerance of the gear ring, with both the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) maintained at low levels. This provides a powerful prediction tools for improving the gear machining accuracy.

2) Feasibility of non-uniform meshing gear shaping accuracy optimization method. Based on the total cumulative pitch deviation and radial runout tolerance of the gear ring predicted by the DA-LSTM model, this study further designed an optimization method for the non-uniform meshing gear shaping accuracy. Through error decoupling, the gear error is accurately assigned to the axes of motion such as the tools radial feed axis, tools rotation axis, and workpiece rotation axis, and the machining parameters are adjusted accordingly. Both the Vericut simulation and experimental validation show that-after adopting this method, the total cumulative pitch deviation and radial runout tolerance of the gear ring of gears were significantly reduced to meet the GB5 accuracy standard, which verifies the feasibility and effectiveness of this optimization method. The feasibility and effectiveness of this optimization method were verified.

3) Advantages of the DA-LSTM model for improving efficiency. Compared to the traditional Monte Carlo method, the DA-LSTM model significantly enhances computational efficiency while maintaining high prediction accuracy. The Monte Carlo method needs to call the original system model thousands of times, which is time-consuming, whereas the DA-LSTM model only requires the original system model a limited number of times (e.g., 140 times) to achieve the same level of accuracy with a significant reduction in the time consumed. This provides an efficient and accurate new method for quantifying the dynamic uncertainty and reliability of gear systems.

The proposed DA-LSTM framework establishes a paradigm-shifting methodology for gear shaping accuracy enhancement, with transformative potential in aerospace and robotics where micron-level transmission precision is mission-critical. Future work will explore real-time DA-LSTM implementations and multi-axis error coupling under dynamic loads.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- F p :

-

Total cumulative pitch deviation (µm)

- F r :

-

Radial runout tolerance (µm)

- \({F}_{a}\) :

-

Profile form deviation (µm)

- \(\:{E}_{x}\) :

-

Tools radial feed axis motion error (mm)

- \(\:{E}_{c}\) :

-

Workpiece rotation axis motion error (deg)

- \(\:{E}_{y}\) :

-

Tools rotation axis motion error (deg)

- \(\:{r}_{c}\) :

-

Radius of gear workpiece (mm)

- \(\:{r}_{y}\) :

-

Radius of tools (mm)

- \(\:{\omega}_{c}\) :

-

Angular velocity of workpiece rotation axis (deg/s)

- \(\:{\omega}_{y}\) :

-

Angular velocity of tools rotation axis (deg/s)

- \(\:{\omega}_{1}\) :

-

Angular velocity of driving gear (deg/s)

- \(\:{\omega}_{2}\) :

-

Angular velocity of driven gear (deg/s)

- \(\:h\) :

-

Center distance between driving and driven gears (mm)

- \(\:Z\) :

-

Number of gear teeth (-)

- \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) :

-

Gear pressure angle (deg)

- \(\:m\) :

-

Gear module (mm)

- \(\:{K}_{ax}\) :

-

Error coefficient for tools radial feed axis (-)

- \(\:{K}_{ac}\) :

-

Error coefficient for workpiece rotation axis (-)

- \(\:{K}_{ay}\) :

-

Error coefficient for tools rotation axis (-)

- \(\:{K}_{rx}\) :

-

Radial runout error coefficient for tools radial feed axis (-)

- \(\:{K}_{rc}\) :

-

Radial runout error coefficient for workpiece rotation axis (-)

- \(\:{K}_{ry}\) :

-

Radial runout error coefficient for tools rotation axis (-)

- \(\:{E}_{1}\) :

-

Theoretical distance between tools and workpiece centers (mm)

- \(\:{E}_{2}\) :

-

Actual distance between tools and workpiece centers (mm)

- RMSE:

-

Root Mean Square Error (mm)

- MAE:

-

Mean Absolute Error (mm)

References

Qiang Guo; Zonglin Liu et al. Development, challenges and future trends on the fabrication of micro-textured surfaces using milling technology. J. Manuf. Process. 126, 285–331 (2024).

Guo, Q. et al. A novel analytical explicit method to calculate formed wheel and tooth flank of involute gears in profile grinding process. ASME J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 145 (6), 061012 (2023).

Donmez, A. & Kahraman, A. Influence of various manufacturing errors on gear rattle. Mech. Mach. Theory. 173, 104868 (2022).

Zhang, C. P. et al. Investigation of dynamic similarity of gear transmission system considering machining error distortion: theoretical analysis and experiments. Mech. Mach. Theory. 172, 104803 (2022).

Zhou, C. J. et al. Effects of centring error and angular misalignment on crack initiation life in herringbone gears. Eng. Fail. Anal. 120, 105082 (2021).

Vivet, M. et al. On the modelling of gear alignment errors in the tooth contact analysis of spiral Bevel gears. Mech. Mach. Theory. 155, 104065 (2021).

Bonori, G. & Pellicano, F. Non-smooth dynamics of spur gears with manufacturing errors. J. Sound Vib. 306, 271–283 (2007).

Driot, N. & Perret-Liaudet, J. Variability of modal behavior in terms of critical speeds of a gear pair due to manufacturing errors and shaft misalignments. J. Sound Vib. 292, 824–843 (2005).

Liu, C. et al. A novel method to predict static transmission error for spur gear pair based on accuracy grade. J. Cent. South. Univ. 27, 3334–3349 (2020).

Guo, F. & Fang, Z. D. The statistical analysis of the dynamic performance of a gear system considering random manufacturing errors under different levels of machining precision. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. ; 234:3–18. (2020).

Zhang, J. & Guo, F. Statistical modification analysis of helical planetary gears based on response surface method and Monte Carlo simulation. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 28, 1194–1203 (2015).

Hu, C. F., Geng, G. D. & Spanos, P. D. Stochastic dynamic load-sharing analysis of the closed differential planetary transmission gear system by the Monte Carlo method. Mech. Mach. Theory. 165, 104420 (2021).

Liu, W. Z. et al. Probability distribution model of gear time-varying mesh stiffness with random pitting of tooth surface. Eng. Fail. Anal. 130, 105782 (2021).

Wei, S. et al. Dynamic response analysis on torsional vibrations of wind turbine geared transmission system with uncertainty. Renew. Energy. 78, 60–67 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by Tianjin University of Technology and Education Research Initiation Fund Project (KYQD1905), Tianjin Science and Technology Program Project(24PTGTQY00100) and Tianjin Metrology Science and Technology Project(2024TJMT073).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fucong Liu wrote the main manuscript text, Luyang Zou prepared Figs. 12 and 13, and 14, and Ze Cao prepared Fig. 19, which all authors reviewed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Zou, L., Cao, Z. et al. Based on Data-Augmentation long short-term memory gear meshing accuracy and error compensation. Sci Rep 15, 13541 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99036-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99036-2