Abstract

The study aims to explore the relationship between mindfulness, rumination thinking, anxiety state, and depressed mood, and the chain mediating roles of rumination thinking and anxiety state in explaining how mindfulness influences depressed mood in infertile women. This cross-sectional study included 946 women with infertility from a maternal and child hospital in western China through convenience sampling. Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), Rumination Response Scale (RRS), Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) were measured as outcome indicators. SPSS PROCESS macro program was used to test for chained mediating effects and the significance using the Bootstrap method. The total effect of mindfulness on depressed mood was -0.390 with the direct path effect of -0.170. The total indirect path effect was -0.220, which accounted for 56.4% of the total effect, and that the chain mediated path (FFMQ→RRS→SAS→SDS) effect was significant with a mediation effect value of -0.075. Mindfulness can not only directly affect infertile women’s depressed mood, but also indirectly affect that through the chain-mediated effects of rumination thinking and anxiety state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is defined as the inability to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular sexual intercourse without contraception1. And it is further categorized into primary and secondary infertility based on whether women have previously been diagnosed with a clinical pregnancy2. Worldwide, the prevalence of infertility is 46.25%3, and the prevalence of infertility in China is 25%4. The diagnosis of infertility is a life crisis for affected couples, with common personal reactions including anger, sadness, stress, anxiety, depression, and altered self-esteem5,6. Previous research has shown that infertile women have a 60% higher risk of psychological distress than the general population, with a 60% higher risk of anxiety and 40% higher risk of depression3. Depressive and anxiety symptoms are also prevalent among infertile patients in China, with significantly higher levels of severity than in the general population7. Women with infertility may experience adverse treatment outcomes as a result of negative emotions that interfere with their regular physiological processes and social interactions8. Therefore, it is important to explore the influencing factors of negative emotions and their mechanisms of action in infertile women.

Mindfulness is the tendency to intentionally and non-judgmentally embrace the experience of the present moment, which is positively correlated with psychological well-being, health behaviors, and quality of life, and negatively correlated with negative physical and psychological states9,10. Studies have shown that high levels of mindfulness can buffer or modulate the adverse effects of stress on the psychological functioning11 and improve patients’ quality of life12,13. In recent years, researcher have probed the role of mindfulness-based interventions and training for addressing psychological challenges in infertile women, such as anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and quality of life14,15,16,17. And several systematic reviews have suggested that mindfulness-based programs reveal significant effects on reducing anxiety and depression symptoms in infertile women to varying degrees and appear to be the safe and viable psychological treatment options18,19,20. Therefore, given the importance and potential benefits may bring, there is a need to investigate the relationship between mindfulness and negative emotions. Based on this, this study proposes hypothesis H1: Mindfulness negatively predicts anxiety and depression levels in infertile women.

When people encounter insurmountable difficulties in their lives, some are immersed in the event, constantly chewing on the negative emotions, which in turn lead to negative behaviors. This thought process of repeatedly thinking about painful emotions is rumination thinking, which also refers to the causes and consequences that arise when people repeatedly think about negative life events21. As a cognitive risk factor for negative emotions such as depression and anxiety, rumination thinking significantly predicts the emergence and development of negative emotions22. According to the available evidence, mindfulness-based interventions can significantly reduce rumination level, enhance mindfulness, and improve anxiety and depression23. Rumination is seen as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy, and mental rumination strategies are positively related with anxiety and depression in infertile women24. And most of the researches on mindfulness and rumination thinking have focused on the direction of reducing rumination thinking through mindfulness-based interventions18,25,26, but failed to address how mindfulness influences rumination level. Nolen-Hoeksema et al. reviewed and hypothesized that by breaking the vicious rumination thinking cycle, mindfulness could help individuals get unstuck by becoming aware of feelings and emotions in a non-judgmental manner27. The study by Yu et al. modeled the effects and investigated the potential mechanisms of mindfulness on negative affect in an adolescent population28. The results suggest that mindfulness would directly relieve anxiety and depression or through the mediating pathway of reducing rumination. In conclusion, mindfulness and rumination are related to anxiety and depression in infertile women19,24 and mindfulness could reduce the mediating role of rumination28. Based on this, this study proposes hypothesis H2: Rumination mediates the relationship between the level of mindfulness and anxiety/depressed mood in infertile women.

Among women who are infertile, anxiety and depression are prevalent and frequently co-occur29. Previous relevant studies have shown that anxiety state is the most common comorbid mental health disorder among those with depressed mood, with estimates of comorbidity ranging from 15 to 75%30. This may be due to individuals in anxiety state exhibit subsyndromal depressive symptoms, but have not yet reached clinical depression31. In a recent longitudinal study over 18 years by Barber et al., anxiety and depressive symptoms interacted with each other and anxiety may predict future depression32. Moreover, anxiety and depression are core factors in psychological problems, and both high levels of anxiety and depression may lead to adverse mental illness and health outcomes33. Ma et al.34 proposed that both mindfulness and rumination are emotion regulation strategies for infertility patients, and decreasing rumination thinking and increasing mindfulness in infertility patients are important ways to reduce anxiety state and depressed mood. Overall, both rumination and anxiety may positively predict future depressed mood24,32, whereas mindfulness on the contrary34. Based on this, this study proposes hypothesis H3: Rumination thinking and anxiety state mediate the relationship between mindfulness and depressed mood in infertile women.

In recent years, research in China and other countries have explored the role of mindfulness and rumination in influencing negative affect such as anxiety and depression in infertile patients17,18,19,24,34. However, most research have not focused on how mindfulness affects negative mood issues and ruminative thinking mediates process in women with infertility. Therefore, this study intends to construct a chain-mediated model to explore how mindfulness improves negative emotions in infertile women in general and to elucidate the mechanisms. Also combining the mindfulness hypothesis on rumination proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema et al.27 and the available empirical evidence, we hypothesized that mindfulness may reduce depressed mood in infertile women through rumination thinking and anxiety state, and further tested this hypothesis in a large sample.

Materials and methods

Design

This study was conducted using a cross-sectional design. The STROBE statement was followed in conducting the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University, with the registration number 2021(195) and was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Setting and participants

The participants of the study were outpatients diagnosed with infertility at the reproductive medicine center of a maternal and child hospital in southwest China from November 2021 to June 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) female patients who met the diagnostic criteria for infertility, including primary and secondary infertility; (2) aged over 20 years; (3) women who were undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) treatment; (4) women who had the ability to complete the questionnaire independently; (5) women who voluntarily enrolled in the study. The exclusion criteria included: (1) women who had a combination of other major diseases (e.g., cancer, severe liver or kidney disease, etc.); (2) women with a history of psychiatric disorders.

The sample size was determined using the Monte Carlo Power Analysis for Indirect Effects program of the Two Serial Mediators Model35. Based on the correlation effects of the initial pilot study results, the target power of 0.9, a significance level of 0.05, and the overall standard deviation of 0.25, the required sample size was 526. Considering the possibility of invalid questionnaires and assuming the dropout rate of 20%, at least 631 participants were needed.

The distribution and collection of the questionnaires was done in the clinic and the completion of the questionnaire content was expected to take 10–15 min. Two researchers administered the questionnaires, with uniform training and instructions before testing. Of the 970 participants who met the criteria, 9 patients refused to participate and 15 incomplete questionnaires were excluded. Finally, 946 valid questionnaires were included in the study (97.5% response rate), meeting the requirement of sample size.

Measurement tools

The questionnaire consisted of a self-administered basic information form (including age, height, weight, education, fertility history, family income, duration and causes of infertility, treatment cost, and vitro fertilization cycle), Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS), Self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and Self-rating depression scale (SDS).

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): Mindfulness was assessed using the FFMQ36. The FFMQ consists of 39 items in 5 dimensions: observation (8 items), description (8 items), acting with awareness (8 items), non-judgment (8 items), and non-reactivity (7 items). The scale was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 to 5 indicating “not conforming at all” to “conforming very much”, and the scores for each dimension were summed to form a total score, with higher scores indicating a higher level of mindfulness. Regardless of language or cultural background, there were significant connections established between overall trait mindfulness and affective symptoms as assessed by the FFMQ37. The test–retest reliability of the scale is 0.784, and the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the subscales were 0.800, 0.807, 0.872, 0.804, and 0.725, respectively.

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS): Rumination level induced by individuals facing negative event elicitation was assessed using the Chinese version of the RRS38, which includes three subscales include symptom rumination, forced thinking, and reflection with a total of 22 items. The scale was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “almost never” (score = 1) to “almost always” (score = 4) with higher scores representing higher levels of rumination and a greater tendency to ruminate. This version was applicable in various groups in China, with good reliability and validity38,39. The reliability of the scale in this study was high, with the Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.946, and the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales were 0.952, 0.829, and 0.776, respectively.

Self-rating anxiety scale (SAS): Anxiety state was measured by the SAS developed by Zung et al.40 in 1971, which consists of 20 self-reported questions rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 according to the frequency of symptoms in the past 7 days. The sum of the scores for each item is the raw score, and the standardized score is equal to the raw score multiplied by 1.25. The threshold of the SAS standardized score is defined as less than 50 as no anxiety, 50–59 as mild anxiety, 60 –69 as moderate anxiety, and 70 and above as severe anxiety41. The Chinese version of the scale has been widely used and has good reliability42. The test-retest reliability of the scale in the study is 0.797.

Self-rating depression scale (SDS): Depressed mood was assessed using the SDS developed by Zung et al.43 in 1971. The SDS has 20 self-reported questions based on symptoms over the past 7 days, with scores ranging from 1 to 4. The raw score is the total of the scores for every item, and the standardized score is the result of multiplying the raw score by 1.25. Less than 50 indicates no depression, 50–59 indicates mild depression, 60–69 indicates moderate depression, and 70 and above indicates severe depression, according to the SAS standardized score. The scale’s Chinese equivalent is highly dependable and is in widespread usage44. The scale in this study has the Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.859.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 statistical software was used to create a database and analyze. A p-value < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant. In order to prevent possible common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was applied to test the initial sample data. Measurement data conforming to normal distribution were expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD), and categorized data were expressed as frequency [n (%)], independent samples t-test was used for comparison between two groups, and single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison between multiple groups. Pearson correlation analysis was used for correlation analysis. The moderated mediated effects test was conducted by using the SPSS macro program PROCESS prepared by Hayes, which firstly constructed a multiple mediated effects model to test the mediated effects of rumination and anxiety state between mindfulness and depressed mood. The standard errors (SE) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the parameter estimates were then further obtained by taking 5,000 Bootstrap samples, and if 95% CI did not include zero, then it was significant45.

Results

Common method bias test

The data collected in this study were filled in by the infertile women themselves and there is a possibility of homogeneity of variance. Therefore, we examined the homoscedastic variance by Harman’s single-factor test in the study. The results showed that there were 20 factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, which accounted for 59.43% of the total variance, while the first common factor accounted for 20.24% of the total loadings when not rotated, which did not meet the 40% criterion, so there was no serious common method bias in this study.

Socio-demographics and scores on each scale

The results of the differences in FFMQ, RRS, SAS and SDS scores of infertile women based on socio-demographic variables are presented in Table S1. 946 study participants were aged from 21 to 48 (32.02 ± 4.22). The total score of mindfulness and rumination were (123.01 ± 13.05) and (39.38 ± 9.98), respectively. Anxiety state score was (42.33 ± 8.11), with 147 cases (15.54%) of mild anxiety, 24 cases (2.54%) of moderate anxiety, and 4 cases (0.42%) of severe anxiety. Depressed mood score was (44.41 ± 10.66), of which 210 cases (22.20%) were mildly depressed, 87 cases (9.20%) were moderately depressed, and 7 cases (0.74%) were severely depressed.

The FFMQ scores of infertile women with different age, education level, monthly family income and duration of infertility were significant (p < 0.05); the RRS scores with different monthly family income, treatment cost and vitro fertilization cycle were compared, and the differences were significant (p < 0.05); the SAS scores with different education level and monthly family income were significant (p < 0.05); the SDS scores with different age, education level, monthly family income, duration of infertility and treatment cost were significant (p < 0.05).

Correlation analysis of mindfulness, rumination, anxiety state and depressed mood

The results of Pearson’s correlation analysis among the scores of each scale are displayed in Table 1. The results showed that the total scores on rumination thinking, anxiety state, and depressed mood were negatively correlated with the total scores on mindfulness (r = -0.404, -0.475, -0.520, p < 0.01). The total scores on anxiety state and depressed mood were positively correlated with the total scores on rumination thinking (r = 0.580, 0.491, p < 0.01). And the total scores on anxiety sate was positively correlated with the total scores on depressed mood (r = 0.681, p < 0.01).

Chain mediating effect analysis

In this study, we constructed a multiple mediated effects model by using depressed mood as the dependent variable, mindfulness as the independent variable, rumination and anxiety state as the mediating variables, and statistically significant socio-demographic variables from the univariate analyses (age, education, monthly family income, duration of infertility, treatment cost, and vitro fertilization cycle) as the control variables.

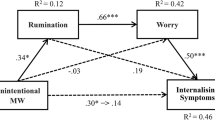

The feasibility of each hypothesis was tested by Stepwise regression equations. The results of the multiple mediating effects of rumination and anxiety state between mindfulness and depressed mood are displayed in Table S2. The model showed that mindfulness negatively predicted depressed mood (β = -0.477, p < 0.001), rumination thinking (β = -0.397, p < 0.001), and anxiety state (β = -0.272, p < 0.001); rumination positively predicted anxiety state (β = 0.460, p < 0.001) and depressed mood (β = 0.110, p < 0.001); anxiety state positively predicted depressed mood (β = 0.660, p < 0.001). The mediation effect and path coefficients in the variables were significant, and the hypothesis chain mediation model was established (Fig. 1).

Based on the chain mediation model, the chain mediation effect was further examined using the SPSS macro PROCESS Model 6 with 5,000 resamples, and the effect values of each path are shown in Table 2. The total effect of mindfulness on depressed mood was -0.390 (95% CI: -0.436, -0.344), and the direct path effect of mindfulness on depressed mood (FFMQ→SDS) was -0.170 (95% CI: -0.213, -0.127), which was a significant direct predictor and accounted for 43.6% of the total effect, then the hypothesis H1 was valid. The total indirect path effect was -0.220 (95% CI: -0.255, -0.186), and three indirect paths were found: Path 1 (FFMQ→RRS→SDS) indicated that rumination had mediating effect between mindfulness and depressed mood, with an indirect effect of -0.033 (95% CI: 0.056, -0.013), which accounted for 15.0% of the total indirect effect, and then the hypothesis H2 was valid; Path 2 (FFMQ→SAS→SDS) showed that anxiety state had mediating effect between mindfulness and depressed mood, with an indirect effect of -0.112 (95% CI: -0.141, -0.084), which accounted for 50.9% of the total indirect effect; Path 3 (FFMQ→RRS→SAS→SDS) showed that rumination and anxiety state had chain mediating effect between mindfulness and depressed mood, with an indirect effect of -0.075 (95% CI: -0.095, -0.058), which accounted for 34.1% of the total indirect effect, and then the hypothesis H3 was valid.

Discussions

In order to investigate the intrinsic mechanisms and individual differences in the effects of mindfulness on depressed mood, the study constructed and analyzed the chain mediation model and effects of rumination thinking and anxiety state on mindfulness and depressed mood in infertile women population. The results showed that mindfulness had a direct negative predictive effect on depressed mood. After introduced intermediate variables into the model, ruminative thinking and anxiety state served as partial mediators and chain mediators in mindfulness and depressed mood.

The study showed that the rate of depressed mood in infertile women was 32.14%, of which 30.92% were moderately severe depression, and the rate of anxiety state was 18.50%, with moderate to severe anxiety accounting for 16%. The result is consistent with the previous study results in China and worldwide3,46. Women who are infertile may experience extreme psychological pain and stress including severe anxiety and depression due to feelings of guilt over not being able to have a baby29,47. In our study, the higher the education level and the monthly family income, the less severe the anxiety and depression, while the longer the duration of infertility and the higher the cost of treatment, the worse the depression among the patients, which is in line with the findings of Fatemeh et al.48. Meanwhile, younger (≤ 25 years) and older (≥ 41 years) infertile women were significantly more depressed than other age stages, which is a little different from the result of other study in which older infertile women showed greater tendency to be depressed49. Younger patients may also be worried and fearful about their physical health and marital status and are more prone to anxiety and depression in the changing socially stressful environment46. Families with low levels of education have more traditional family attitudes and atmospheres, and are therefore more likely to receive pressures from society and the family members, and thus show greater tendencies towards anxiety and depression50. The results in the study highlight an important and growing mental disorder that may be overlooked in the population of infertile women with these characteristics and should be of concern to healthcare professionals and society, thus helping to achieve a more positive outcome.

The result in the study indicated that mindfulness in infertile women directly and negatively predicted depressed mood, consistent with the result of a retrospective study by Wang et al.19 and confirming the hypothesis H1. For infertile women with low level of mindfulness, previous study has shown that although conventional psychotherapy can improve patients’ depressed mood to a certain extent, the treatment process is lengthy and the short-term effects are not very satisfactory51. Mindfulness training is designed to guide patients to look at their feelings and painful thoughts with an open and accepting attitude, to be aware of their physical and emotional state without judgment, and to urge patients to face rather than avoid existing or potential difficulties, so that they can actively accept their own emotions52. An in-depth study by Hare et al.53 showed that mindfulness significantly activates prefrontal cortical areas (related to an individual’s consciousness and emotion regulation), and anterior cingulate cortical areas (related to attention) in the structure of brain regions, which are inextricably linked to the generation, maintenance, and regulation of the negative mood. This suggests that the establishment and enhancement of mindfulness is of practical significance in alleviating depressed mood in infertile women. Medical personnel should pay more attention to mindfulness training for infertile women to improve the level of mindfulness and prevent negative affect.

The mediation effect model in this study showed that rumination thinking and anxiety state acted as partial mediators and chain mediators between mindfulness and depressed mood in infertile women, which indicates that the hypothesis H2 and H3 are valid. Individuals with high level of mindfulness had lower level of rumination, anxiety state, and depressed mood, which is also consistent with previous findings9,10,25,26. Meanwhile, rumination positively predicted anxiety state and depression, which may be due to the fact that rumination, as a negative way of thinking characterized by negative thought content, negative interpersonal contexts, and interpretive level of abstraction54, is therefore considered a cognitive vulnerability factor for anxiety and depression, deepening the negative emotions22. According to the response model of mindfulness55, it can be seen that when facing negative life events, the positive cognitive reappraisal of mindfulness plays a key role in helping individuals adopt a decentered adaptive approach, and further mitigating the negative effects of rumination thinking, thus inhibiting the generation of negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. Deyo et al.56 found that elevating the level of mindfulness through mindfulness training can alleviate rumination thinking in depressed people. In addition, the study also showed that anxiety state positively predicted depression mood. It is in accordance with the results of Choi et al.57, which suggested that reduced negative feedback in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with depressive disorders may be induced and maintained by anxiety. Mindfulness intervention study by Chen et al.58 also confirmed that there is a correlation between the anxiety state and the degree of depression, and that mindfulness stress reduction ability are utilized to regulate cognition, alleviate physical stress effects, improve optimistic and positive cognition, and correct biased cognition, thus alleviating the symptoms of depression and anxiety. Therefore, the findings suggest that rumination and anxiety state are important bridges for mindfulness to modulate depressed mood, and are an important perspective for revealing the intrinsic mechanisms of mindfulness interventions for depressed mood in infertile women.

In conclusion, when infertile women are psychologically disturbed, anxiety state and depressed mood can be further reduced by increasing the level of mindfulness and decreasing rumination thinking. This study reveals the effects of mindfulness on negative emotions and their underlying mechanisms in infertile women, which is important for positively guiding and preventing the development of negative emotions and their resulting adverse treatment outcomes. As infertile women are vulnerable to depression, medical personnel should emphasize their mental health and provide regular psychological interventions based on mindfulness to effectively reduce the incidence of depression.

Strengths and limitations

The findings have some theoretical value and practical guidance for the detection and intervention of negative emotions in infertile women, but there are some limitations. Firstly, this study was a cross-sectional study without longitudinal follow-up, so it could be unable to discuss long-term effects between variables. Longitudinal follow-up or experimental intervention design studies can be conducted further so as to analyze the whole mediation process and key nodes comprehensively. Secondly, the data of the study were based on the self-report of the participants, social expectations may be involved in the process of filling in the data, thus affecting their true reflection and making the objectivity of the data somewhat biased. In addition, the sample of this study came from a single hospital, and the generalizability of the findings needs to be verified in more multicenter studies in the future. Finally, because of many factors affecting the explanatory variables, the established chain mediation model is not the only mediation model, and there may be other mediating variables. Therefore, the findings of this study are only a part of the mechanisms influencing negative emotions in infertile women, and there are more mediating variables and intrinsic mechanisms that deserve to be validated and applied in future studies.

Conclusions

The study results show that the current status of depressed mood in infertile women requires urgent clinical attention. Mindfulness can directly influence depressed mood in infertile women and can also be indirectly mediated through rumination and anxiety state. Rumination and anxiety form a chain mediation pathway of action in the relationship between mindfulness and depressed mood. This study emphasizes the importance of elevating mindfulness and assessing anxiety states in the early stages of depressive disorders in infertile women. And the mindfulness interventions should be integrated with the value of targeting rumination to prevent and improve depression symptoms, which may contribute to improve the mental health of the infertile women population.

Data availability

Data detailed in the manuscript will not be made publicly available because private information of participants was included, but are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Organization, W. H. Infertility Definitions and Terminology. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions/en/ (2015).

Zegers-Hochschild, F. et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care. Fertil. Steril. 108, 393–406 (2017).

Nik Hazlina, N. H., Norhayati, M. N. & Bahari, S. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 12, e057132 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Epidemiology of infertility in China: a population-based study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 125, 432–441 (2018).

Omu, F. E. & Omu, A. E. Emotional reaction to diagnosis of infertility in Kuwait and successful clients’ perception of nurses’ role during treatment. BMC Nurs. 9, 5 (2010).

Schmidt, L. Social and psychological consequences of infertility and assisted reproduction—what are the research priorities? Hum. Fertil. (Cambridge, England). 12, 14–20 (2009).

Yang, B. et al. Assessment on occurrences of depression and anxiety and associated risk factors in the infertile Chinese men. Am. J. Men’s Health. 11, 767–774 (2017).

Simionescu, G. et al. The complex relationship between infertility and psychological distress (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 21, 306 (2021).

Chahar Mahali, S., Beshai, S. & Wolfe, W. L. The associations of dispositional mindfulness, self-compassion, and reappraisal with symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of Indigenous students in Canada. J. Am. Coll. Health JACH. 69, 872–880 (2021).

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Clear, S. J. & Campbell, S. M. Peer relationships and stress: indirect associations of dispositional mindfulness with depression, anxiety and loneliness via ways of coping. J. Adolesc. 93, 177–189 (2021).

Bränström, R., Duncan, L. G. & Moskowitz, J. T. The association between dispositional mindfulness, psychological well-being, and perceived health in a Swedish population-based sample. Br. J. Health. Psychol. 16, 300–316 (2011).

Morgan, L. P., Graham, J. R., Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Orsillo, S. M. & Roemer, L. Relationships between amount of post-intervention of mindfulness practice and follow-up outcome variables in an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: the importance of informal practice. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 3, 173–176 (2014).

Murray, G. et al. Towards recovery-oriented psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: quality of life outcomes, stage-sensitive treatments, and mindfulness mechanisms. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 52, 148–163 (2017).

Arani, A. M. et al. The comparative efficacy of unified transdiagnostic protocol (UP) and mindfulness-based stress reduction protocol (MBSR) on emotion regulation and uncertainty intolerance in infertile women receiving IVF. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 30, 578–588 (2023).

Baghbani, F. et al. Efficacy of dry cupping versus counselling with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy approach on fertility quality of life and conception success in infertile women due to polycystic ovary syndrome: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. 12, 57–69 (2024).

Kalhori, F., Masoumi, S. Z., Shamsaei, F., Mohammadi, Y. & Yavangi, M. Effect of mindfulness-based group counseling on depression in infertile women: randomized clinical trial study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 14, 10–16 (2020).

Nery, S. F. et al. Mindfulness-based program for stress reduction in infertile women: randomized controlled trial. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress. 35, 49–58 (2019).

Shuang, C. A. I. & Zhang Zhongye. C. L.,. Effectiveness of mindfulness therapy on negative emotion in infertiie women: A meta-anaIysis. China J. Health Psychol. 30 (2022).

Wang, G., Liu, X. & Lei, J. Effects of mindfulness-based intervention for women with infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Women Ment. Health. 26, 245–258 (2023).

Wen, Y. et al. The effects of mindfulness therapy on infertile female patients: A meta-analysis. Technol. Health Care: Off. J. Eur. Soc. Eng. Med. (2024).

Dunning, D. L. et al. Research review: the effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 60, 244–258 (2019).

Roelofs, J., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., Arntz, A. & van Os, J. Rumination and worrying as possible mediators in the relation between neuroticism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in clinically depressed individuals. Behav. Res. Ther. 46, 1283–1289 (2008).

Li, P. et al. Mindfulness on rumination in patients with depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (2022).

Mirzaasgari, H., Momeni, F., Pourshahbaz, A., Keshavarzi, F. & Hatami, M. The relationship between coping strategies and infertility self-efficacy with pregnancy outcomes of women undergoing in vitro fertilization: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 20, 539–548 (2022).

Chiesa, A. & Serretti, A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. (New York N Y). 15, 593–600 (2009).

Perestelo-Perez, L., Barraca, J., Peñate, W., Rivero-Santana, A. & Alvarez-Perez, Y. Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of depressive rumination: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. IJCHP. 17, 282–295 (2017).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E. & Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 3, 400–424 (2008).

Yu, M., Zhou, H., Xu, H. & Zhou, H. Chinese adolescents’ mindfulness and internalizing symptoms: the mediating role of rumination and acceptance. J. Affect. Disord. 280, 97–104 (2021).

Gdańska, P. et al. Anxiety and depression in women undergoing infertility treatment. Ginekol. Pol. 88, 109–112 (2017).

Yorbik, O., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D., Williamson, D. E. & Ryan, N. D. Clinical characteristics of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 65, 1654–1659 (2004). quiz 1760 – 1651.

Van Voorhees, B. W., Melkonian, S., Marko, M., Humensky, J. & Fogel, J. Adolescents in primary care with sub-threshold depressed mood screened for participation in a depression prevention study: co-morbidity and factors associated with depressive symptoms. open. Psychiatry J. 4, 10–18 (2010).

Barber, K. E., Zainal, N. H. & Newman, M. G. The mediating effect of stress reactivity in the 18-year bidirectional relationship between generalized anxiety and depression severity. J. Affect. Disord. 325, 502–512 (2023).

Wigman, J. T. et al. Evidence that psychotic symptoms are prevalent in disorders of anxiety and depression, impacting on illness onset, risk, and severity—implications for diagnosis and ultra-high risk research. Schizophr. Bull. 38, 247–257 (2012).

Ma Dandan, B. C. & Fangxiang, M. ReIation of emotion reguiation strategies to depression and anxiety symptoms in infertile patients. Chin. Ment. Health J. 37, 662–671 (2023).

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J. & Short, S. D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. 8, 379–386 (2017).

Meng, Y., Mao, K. & Li, C. Validation of a short-form five facet mindfulness questionnaire instrument in China. Front. Psychol. 10, 3031 (2019).

Carpenter, J. K., Conroy, K., Gomez, A. F., Curren, L. C. & Hofmann, S. G. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: A meta-analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 74, 101785 (2019).

Han Xiu, Y. H. A trial of the Nolen–Hoeksema ruminate thinking scale in China. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. (2009).

Xu Yongrong, Y. L., Lingxia, M., Xia, H. & Jiemei, G. Dementia and quality of life in patients with malignant tumors: the mediating role of ruminative thinking. Chin. J. Pract. Nurs. 40, 8 (2024).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12, 371–379 (1971).

Gainotti, G., Cianchetti, C., Taramelli, M. & Tiacci, C. The guided self-rating anxiety-depression scale for use in clinical psychopharmacology. Activitas Nervosa Superior. 14, 49–51 (1972).

Gong, Y. et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and related risk factors among physicians in China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 9, e103242 (2014).

Zung, W. W. & Gianturco, J. A. Personality dimension and the self-rating depression scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 27, 247–248 (1971).

Chen, S. B. et al. Prevalence of clinical anxiety, clinical depression and associated risk factors in Chinese young and middle-aged patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. PLoS One. 10, e0120234 (2015).

Holland, S. J., Shore, D. B. & Cortina, J. M. Review and recommendations for integrating mediation and moderation. Organ. Res. Methods. 20, 686–720 (2016).

Wang, L., Tang, Y. & Wang, Y. Predictors and incidence of depression and anxiety in women undergoing infertility treatment: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 18, e0284414 (2023).

Rooney, K. L. & Domar, A. D. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 20, 41–47 (2018).

Ramezanzadeh, F. et al. A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Women’s Health. 4, 9 (2004).

Ogawa, M., Takamatsu, K. & Horiguchi, F. Evaluation of factors associated with the anxiety and depression of female infertility patients. Biopsychosoc. Med. 5, 15 (2011).

Ried, K. & Alfred, A. Quality of life, coping strategies and support needs of women seeking traditional Chinese medicine for infertility and viable pregnancy in Australia: a mixed methods approach. BMC Women’s Health. 13, 17 (2013).

Dong Yana, G. B. & Jingjing, H. The effect of mindfulness decompression therapy on anxiety, depression and sleep quality in infertility patients. J. Int. Psychiatry. 47, 774–781 (2020).

Irving, J. A. & Segal, Z. V. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: current status and future applications. Sante Mentale Au Quebec. 38, 65–82 (2013).

Hare, B. D. & Duman, R. S. Prefrontal cortex circuits in depression and anxiety: contribution of discrete neuronal populations and target regions. Mol. Psychiatry. 25, 2742–2758 (2020).

Watkins, E. R. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol. Bull. 134, 163–206 (2008).

Garland, E., Gaylord, S. & Park, J. The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore (New York N Y). 5, 37–44 (2009).

Deyo, M. et al. Mindfulness and Rumination: Does Mindfulness Training Lead to Reductions in the Ruminative Thinking Associated With Depression? Explore 5, 265–271 (2009).

Choi, K. W., Kim, Y. K. & Jeon, H. J. Comorbid anxiety and depression: clinical and conceptual consideration and transdiagnostic treatment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1191, 219–235 (2020).

Chen Yuanyuan, L. A., Li, T. Effects of positive stress reduction therapy on anxiety and depression levels and sleep quality in pregnant women with gestational hypertension. Psychol. Mag.. 7, 61–62 (2021).

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Nursing, West China Second University Hospital for Scientific Research (Grant number: HLBKJ202130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L.: Writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, methodology, formal analysis, conceptualization. B.L.: Writing—review and editing, supervision, methodology, conceptualization. Z.W.: Writing—review and editing, investigation, formal analysis. X.L: Writing—review and editing, supervision, methodology, funding acquisition, conceptualization. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University, and the approval number was Medical Research 2021 Ethical Approval No. 195. All study participants volunteered to participate in this study and gave their informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, S., Luo, B., Wei, Z. et al. Chain mediation of rumination and anxiety state between mindfulness and depressed mood in infertile women. Sci Rep 15, 14199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99147-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99147-w