Abstract

Studies on the impact of gram-positive extracellular vesicles have paved the way for novel medical advancements. These vesicles serve as efficient carriers of microbial molecules to target cells, thereby influencing human pathophysiological processes. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the anti-inflammatory properties of extracellular vesicles derived from Lactobacillus gasseri GFC-1220 (LEVs) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. LEVs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and dynamic light scattering measurements to examine their morphology, size, and concentration. We further assessed the anti-inflammatory effects of LEVs and their underlying mechanism in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Our findings revealed that LEVs did not cause cytotoxic effects and significantly decreased the level of mitochondria superoxide and reactive oxygen species production. In addition, these vesicles effectively inhibited the LPS-induced activation of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, consequently suppressing the secretion and expression of various pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines. These included a reduction in the production of NO and PGE2, along with their corresponding producer enzymes iNOS and COX-2, as well as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β cytokines. These findings strongly suggest that LEVs have significant potential for the development of new anti-inflammatory agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane-bound spherical nanostructures produced by both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, playing a crucial role as mediators of intercellular communication1. The growing research on the human microbiota’s role in health and disease has significantly heightened interest in microbial-derived EVs and their functional roles in cellular communication, delivery of virulence factors, and modulation of host immunity2. Accumulating evidence suggests that microbe-host interactions can profoundly influence host health, impacting processes such as nutrient metabolism, maintenance of the intestinal barrier, and the regulation of immune responses3. The Human Microbiome Project has cataloged over 2000 species of prokaryotes isolated from the human body, highlighting the vast diversity of bacterial life that interacts with the host4. Within this context, research on bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) has gained momentum, particularly in exploring their immunomodulatory properties and potential as targeted carriers for therapeutic interventions5.

Lactobacillus, a genus of gram-positive bacteria widely recognized as non-pathogenic, has been the subject of extensive laboratory and clinical research due to its potential health benefits6,7. Notably, BEVs derived from various Lactobacillus strains have demonstrated immunomodulatory effects, making them promising candidates for drug delivery systems in managing inflammatory disorders8,9. For instance, BEVs from Lactobacillus paracasei have shown therapeutic potential in attenuating lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced intestinal inflammation through the activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress10. Similarly, BEVs derived from Lactobacillus plantarum have been found to suppress inflammatory responses in Staphylococcus aureus-induced atopic dermatitis by inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-4 (IL-4)11. Among the Lactobacillus species, Lactobacillus gasseri is particularly notable for its resilience to acidic gastric conditions and its beneficial effects in alleviating allergic diseases, regulating oxidative stress, and exerting anti-inflammatory activities12. However, despite these promising attributes, research on the immunomodulatory properties of BEVs derived from L. gasseri remains limited, indicating a significant area for exploration.

Inflammation is a complex physiological response triggered by foreign organisms such as human pathogens, dust particles, and viruses13. It can be broadly categorized into acute and chronic inflammation, depending on the underlying inflammatory processes and cellular mechanisms involved14. The resolution of inflammation has emerged as a crucial endogenous process that protects host tissues from prolonged or excessive inflammation, which can otherwise become chronic15. The failure to resolve inflammation is a key pathological mechanism that contributes to the progression of numerous inflammation-driven diseases16. Among immune cells, macrophages play a central role in orchestrating immune responses through various intrinsic signaling cascades17. Upon activation during acute inflammation, macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators such as IL-6, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and nitric oxide (NO)18. Therefore, inhibiting the production of these cytokines and mediators represents a promising approach for designing effective anti-inflammatory agents.

In this study, we investigate whether the BEVs isolated from L. gasseri (LEVs) exhibit anti-inflammatory activity in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. In addition, we explored the underlying inhibitory mechanisms, focusing on potential signaling pathway. The findings of this study may contribute to the development of LEVs as a novel therapeutic strategy for managing inflammatory diseases, with potential application as targeted carriers for drug delivery.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine the taxonomic placement of L. gasseri GFC-1220, we performed a maximum likelihood analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences. While 16S rRNA gene sequencing remains a cornerstone of bacterial taxonomy due to its reliability in defining phylogenetic relationships at higher taxonomic levels, it is limited in its resolution at the species level, owing to conserved sequence regions shared among closely related species19. Despite these constraints, our analysis demonstrated that the L. gasseri GFC-1220 strain belongs to the genus Lactobacillus and is mostly related to L. paragasseri JCM 5343, as shown in Fig. 1.

Characterization of LEVs

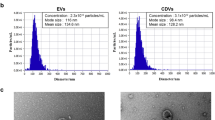

To examine the structural properties (size, distribution, and morphology) of LEVs, three independent techniques were used: transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Initially, Cryo-EM revealed that LEVs had a spherical structure with a bilayer membrane, as indicated by yellow and red arrows, suggesting a potential double membrane of LEVs as shown in Fig. 2A. The sizes of LEVs detected using Cryo-EM ranged from 60 to 100 nm, similar to the previously described gram-positive BEVs20,21. Subsequently, the particle sizes of LEVs were determined by NTA. The results showed that most of the vesicles were approximately 99.1 ± 24.5 nm in diameter (Fig. 2B). The number of particles per mL was 1.9 × 1012 ± 0.5 × 1012. DLS was employed to measure the zeta potential and confirm the particle size of LEVs. The results indicated a size range of 70–140 nm, with an average size of 96.1 ± 15.7 nm, consistent with the findings from Cryo-EM and NTA (Fig. S1). The stability of LEVs was evaluated using zeta potential measurement which indicated the stability value was − 57.1 ± 0.3 mV, suggesting its high stability (Fig. 2C).

Cytotoxicity of LEVs in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells

The potential cytotoxicity of LEVs in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells was assessed using both MTT assay and live/dead staining after 24 h of treatment. As shown in Fig. 3A, LEVs exhibited no significant cytotoxic effects at concentrations of 1, 1.5, and 2 × 1010 particles/mL, with cell viability remaining above 90%, as determined by the MTT assay. Similarly, dexamethasone (DEX) was used as a positive control due to its well-documented anti-inflammatory properties and lack of cytotoxic effects at the concentration of 1 μM. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that DEX does not significantly impact cell viability at similar concentrations in RAW264.7 cells22,23. Consistent with the MTT results, the live/dead staining assay indicated no considerable cytotoxic effects of LEVs on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B). These collective data strongly suggested that LEVs at concentration of 1, 1.5, and 2 × 1010 particles/mL did not induce cytotoxicity in RAW264.7 cells.

Effects of LEVs on cell viability. The effect of LEVs on the viability of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells using MTT assay (A); and live/dead staining, with live cells (green color) and dead cells (red color) (B). Significant differences between groups are indicated by different superscripts, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Effects of LEVs on LPS-stimulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and mitochondrial superoxide (Mito-SOX)

ROS production plays an important role in macrophage differentiation and activation of key inflammatory signaling pathways24. In this study, we evaluated the impact of LEVs on Mito-SOX and ROS formation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. LPS treatment significantly increased the fluorescence intensity of ROS (green), and Mito-SOX (red) compared to the control group. In contrast, these effects were reversed by treatment with DEX. DEX’s effect on ROS production was included as a reference point, given its known ability to suppress oxidative stress25,26. Similarly, LEVs treatment at a concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL substantially reduced the fluorescence intensity by 56.7% for ROS and 71.7% for Mito-SOX (Fig. 4). These results indicated that LEVs effectively inhibited ROS and Mito-SOX level in LPS- stimulated RAW264.7 cells.

LEVs treatment suppressed LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression associated with the production of NO and PGE2

NO and PGE2 are key inflammatory mediators secreted by macrophages. Therefore, we initially assessed their levels in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells after treatment with LEVs. As shown in Fig. 5A, the control group exhibited minimal NO release (0.7 ± 0.2 μM), whereas the LPS-treated group showed a significant increase (57.4 ± 0.7 μM). LEVs treatment effectively decreased the LPS-induced NO secretion in a dose dependent manner (37.8 ± 2.9 μM, 22.4 ± 1.5 μM, 10.9 ± 0.4 μM at the concentration of 1, 1.5, 2 × 1010 particles/mL, respectively). Similarly, PGE2 levels were substantially reduced after treatment with LEVs in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Compared to the LPS treated group (21,805.4 ± 1580.3 pg/mL), LEVs significantly inhibited PGE2 production to 10,160.4 ± 878.7 pg/mL at 2 × 1010 particles/mL concentration (Fig. 5B).

Effects of LEVs on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators in RAW264.7 macrophages. The suppressed effect of LEVs on NO production (A); and the secretion of PGE2 measured in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages (B); The effect of LEVs on the LPS-induced gene expression of iNOS (C) and COX-2 (D). The inhibitory effect of LEVs on the IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β secretion (E) and gene expression (F) in the activated RAW264.7 cells. Significant differences between groups are indicated by different superscripts, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

To elucidate whether the effect of LEVs was mediated through the regulation of corresponding gene expression, qRT-PCR was conducted to evaluate the mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2. The results revealed a dramatic decrease in the iNOS and COX-2 expression following LEVs treatment compared to LPS-treated group in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5C,D). Particularly, treatment with LEVs at the concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL reduced the expression of iNOS and COX-2 by 66.5% and 51.9%, respectively, relative to the LPS-treated group. Taken together, these findings indicated that LEVs attenuated LPS-induced NO and PGE2 production by down-regulating iNOS and COX-2 gene expression.

Effects of LEVs on the secretion and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

In the progression of inflammation, the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β are notably elevated, playing a significant role in cellular response to inflammatory stimuli27. Therefore, we investigated the secretion of these cytokines in RAW264.7 cells stimulated by LPS after LEVs treatment. Compared to the control group, LPS markedly increased the release of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β cytokines, reaching levels of 21,357.8 ± 1169.2 pg/mL, 36,287.5 ± 1667.4 pg/mL, and 5439.4 ± 458.4 pg/mL, respectively. However, treatment with LEVs at a concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL significantly reduced these cytokine levels to 8896.7 ± 1429.8 pg/mL, 21,119.3 ± 1302.7 pg/mL, and 1219.8 ± 174.2 pg/mL, respectively (Fig. 5E). Additionally, we assessed the effect of LEVs on the down-regulation of LPS-stimulated IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β gene expression. LEVs treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the mRNA levels of all three cytokines. In particular, at a concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL, LEVs reduced the expression of IL-6 and IL-1β more effectively than the DEX treatment group (Fig. 5F). These findings suggested that LEVs attenuated both the secretion and expression of LPS-mediated IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β cytokines in RAW264.7 cells.

Effects of LEVs on the suppression LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells via TLR4 receptor

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a prominent role in initiating immune responses and regulating macrophages polarization28. In particular, TLR4, a well-studied member of this family, is highly expressed on the surface of macrophages and is critical for recognizing LPS, which in turn triggers macrophage differentiation and stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines29. To explore the role of LEVs in mitigating inflammation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, we conducted a 12 h treatment with both LPS and TAK-242, a TLR4 antagonist, to assess this interaction. As shown in Fig. 6A,B, TAK-242 significantly suppressed LPS-induced secretion and expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in RAW264.7 cells. In addition, co-treatment with LEVs and TAK-242 effectively enhanced the inhibitory effects of TAK-242 on the release and mRNA level of these cytokines. These results revealed that LEVs contributed to the suppression of LPS-stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine production and expression in RAW264.7 macrophages by targeting TLR4.

Effects of LEVs on the release and gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells treated with TAK-242 inhibitor. IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β secretion (A); IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression (B). Significant differences between groups are indicated by different superscripts, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Molecular mechanism underlying anti-inflammatory activity induced by LEVs

To further elucidate the downstream mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of LEVs, qRT-PCR and western blot analyses were performed to assess their impact on the key mRNA and protein expression in the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 7A, LPS significantly increased the expression of TLR4, myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 4 (IRAK-4), inhibitory-κB kinase alpha (IKK-α), and phospho-NF-κB p65 (p65), compared to the untreated group. However, treatment with LEVs at a concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL notably attenuated these gene expressions. To verify whether LEVs could suppress LPS-induced inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB pathway, the total and phosphorylated proteins were assessed. Upon LPS stimulation, phosphorylation of IκBα and p65 significantly increased in the LPS-treated group, reaching levels 6.3 and 8.8 times higher than those of the control group, respectively. Nevertheless, 2 × 1010 particles/mL of LEVs treatment substantially reduced the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65 to 3.7 and 5.3, respectively (Fig. 7B). These results strongly suggested that LEVs consistently exhibited anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines through regulation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Effects of LEVs on the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. The inhibitory effects of LEVs on the gene expression analysis of TLR4/NF-κB pathway (A); and western blot analysis of NF-κB pathway (B). Samples for the same marker were obtained from the same blot. Original and full-length blots are presented in supplementary Fig. S2. Significant differences between groups are indicated by different superscripts, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Discussion

BEVs are typically categorized into two groups: gram-negative and gram-positive. Unlike gram-negative bacteria, gram-positive bacteria have historically received less attention for EVs production because of their thick peptidoglycan cell walls, were thought to prevent the release of membrane-derived vesicles30. However, recent evidence suggests that cell wall-degrading enzymes may weaken these barriers, allowing the release of EVs31. Although cell wall-degrading enzymes have been proposed as a primary mechanism facilitating the release of EVs in gram-positive bacteria, other mechanisms may contribute to this process. One possibility is the role of turgor pressure, which contributes to membrane curvature, facilitating the selective packaging of biomolecules such as proteins, DNA, RNA, and lipids during vesicle formation32. Subsequently, specific proteins, such as alpha phenol-soluble modulins, play a vital role in disrupting membranes, thereby promoting the formation and release of EVs from the plasma membrane33. Additionally, autolysin and antibiotics targeting penicillin-binding proteins can weaken the peptidoglycan layer, further promoting the liberation of EVs32. Consequently, there is a growing recognition of BEVs production by gram-positive bacteria, a sparking interest in understanding their biogenesis and interactions with host cells.

BEVs associated molecules are sensed by cell-surface and intracellular receptors, and they trigger innate immune signaling leading to both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses34. BEVs have emerged as key elements in immunological mechanisms of the body35. For instance, EVs produced by the human gut bacterium Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron have been shown to influence host immune pathways in a cell-type-specific manner, with their effects partly attributed to the modulation of TLR4 activity36. Additionally, EVs have been demonstrated to modulate host-microbe interactions by altering TLR2 activity, further illustrating their role in immune regulation37. Recent studies have also highlighted the immunomodulatory potential of BEVs derived from probiotic species, particularly in regulating NF-κB and TLR signaling pathways. For example, Masaki et al. reported that probiotic-derived EVs activate innate immunity through TLR2-mediated NF-κB and MAPK pathways, emphasizing their role in modulating host immune responses38. Furthermore, EVs from Propionibacterium freudenreichii strains exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity by modulating the NF-κB signaling cascade39. These findings expand the understanding of BEVs’ immunoregulatory effects, suggesting that EVs from diverse probiotic species hold significant promise as therapeutic agents for immune-related disorders.

In addition to these genera, BEVs from Lactobacillus species have demonstrated notable therapeutic potential in inflammatory conditions. For instance, a study demonstrated that BEVs derived from L. kefirgranum PRCC-1301 exerted anti-inflammatory efficacy on colitis by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and improving intestinal barrier function40. Similarly, BEVs from L. plantarum APsulloc 331261 have been found to promote anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization in human monocytic THP1 cells and skin organ cultures20. Additionally, BEVs from L. plantarum Q7 alleviated DSS-induced ulcerative colitis symptoms, restored gut microbiota balance, and promoted microbial diversity41. These findings suggest that BEVs from Lactobacillus spp. have therapeutic potential in various inflammatory conditions. In the present study, we successfully isolated BEVs from L. gasseri GFC-1220, with most of particles measuring at 99.1 ± 24.5 nm in size. Cryo-EM analysis confirmed that these LEVs were closed, spherical membrane-bound vesicles, characteristic of EVs derived from gram-positive bacteria. Zeta potential indicated -57.1 ± 0.3 mV suggesting that LEVs possess a stable surface charge, which is essential for maintaining vesicle integrity and interaction with target cells. We further demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of LEVs on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents in inflammatory conditions.

Chronic inflammation is a well-established initiator and promoter of several human diseases including COVID-19, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson disease, and various types of cancer42,43,44,45. Macrophages, key immune cells in the innate immune system, are an important host defense against the pathogenesis of many infectious, immunological, and degenerative disease processes46. LPS, a primary component found in the cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria, induces a significant increase in ROS generation, leading to damage of cellular components such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids47. Beyond cellular damage, ROS acts as critical signaling messengers that regulate various kinases and transcription factors involved in the initiation and progression of inflammation48. Studies have demonstrated that LPS stimulates macrophages to secrete high levels of inflammatory mediators such as NO and PGE2, along with their respective synthases iNOS and COX-2. Moreover, LPS triggers the release of cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β27,49. Therefore, developing agents capable of suppressing these pro-inflammatory factors is essential. Our findings indicated that LEVs effectively attenuated ROS Mito-SOX level, as well as the secretion and gene expression of the above-mentioned pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages. These results are consistent with those of a previous study on L. gasseri 4M13, which has exhibited inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase activity, cholesterol reduction, and the suppression of NO production and inflammatory cytokines in LPS-treated RAW264.7 macrophages50.

LPS-induced oxidative stress is a well-established driver of inflammation, with excessive ROS serving as signaling molecules that activate pro-inflammatory pathways, including the TLR4/NF-κB signaling cascade51. The antioxidant ability of LEVs is closely linked to their anti-inflammatory effects, as reducing oxidative stress mitigates the activation of these inflammatory pathways52. To investigate this relationship, we examined the impact of LEVs on the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway using qRT-PCR and western blotting analyses. To further assess whether LEVs could modulate the LPS-stimulated TLR4/NF-κB signaling cascade, LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells were treated with TAK-242, a TLR4 inhibitor, and LEVs. Our findings demonstrated that TAK-242 enhanced the inhibitory effects of LEVs on the secretion and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β. This suggests that TLR4 receptor plays a crucial role in mediating the anti-inflammatory effect of LEVs. TLR4 triggers the activation of downstream protein adaptors such as MyD88, leading to the recruitment and activation of IRAK-4 and TRAF-653. These kinases further in turn activate IKK-α, which phosphorylates the IκBα proteins, resulting in the release of nuclear translocation of NF-κB. In the nucleus, NF-κB promotes the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes54. Therefore, substances capable of down-regulating these cascades hold promise for the development of anti-inflammatory therapies. In our study, 2 × 1010 particles/mL of LEVs treatment substantially decreased TLR4/NF-κB-related genes including TLR4, MyD88, IRAK-4, TRAF-6, and p65 in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Subsequently, we assessed the ability of LEVs to influence two key translation factors (IκBα and p65) in the NF-κB cascade and found that LEVs at a concentration of 2 × 1010 particles/mL significantly suppressed the phosphorylation expression levels of IκBα and p65 compared to those in the cells treated with LPS alone. Taken together, these results indicate that LEVs can effectively down-regulate TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells, thereby alleviating the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, cytokines, and their corresponding genes. Nonetheless, our study has some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. One major limitation is the incomplete understanding of the communication mechanisms between LEVs and RAW264.7 cells. Previous study suggests that the transport of small RNA fragments from EVs to the host can regulate the host metabolism and immune responses55. Therefore, further comprehensive analyses of the molecular components within LEVs, employing advanced techniques such as proteomics or transcriptomics, are necessary. Such insights could significantly advance the development of LEVs as therapeutic candidates for managing inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, or metabolic disorders associated with chronic inflammation. While our findings demonstrate the anti-inflammatory potential of LEVs in vitro, their effects in vivo may differ due to factors such as bioavailability, systemic distribution, and the complexity of the immune environment. Concentration is also a critical factor, as the optimal dose may vary in vivo to balance efficacy and safety. Future research should focus on validating these effects in animal models of inflammation to assess pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and immune-modulatory effects, as well as exploring strategies to enhance EV stability and delivery in more complex settings. With continued investigation, LEVs may apply in functional foods or nutraceuticals aimed at inflammation management, offering a natural, biologically derived alternative to conventional anti-inflammatory treatment, potentially with fewer side effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study successfully isolated BEVs from the probiotic bacterium L. gasseri GFC-1220 and demonstrated their potent anti-inflammatory effects in vitro. The results showed that LEVs effectively suppressed inflammatory activation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, primarily by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. This suppression reduced the secretion and expression of key pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines. Additionally, LEVs significantly decreased ROS production and Mito-SOX level, further contributing to their anti-inflammatory activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that LEVs hold promise as anti-inflammatory agents for treatment macrophage-mediated inflammatory conditions. Future studies focusing on the molecular characterization of LEV components will be essential to fully harness their potential in developing innovative, bio-based therapies for inflammation management.

Materials and methods

Reagents

RAW264.7 cells were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin GenDEPOT (Katy, TX, USA) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. LPS, DEX, TAK-242, and 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies of NF-κB, p-NF-κB, IκBα, p-IκBα and β-actin were provided by Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Secondary anti-mouse/rabbit antibodies were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). The gene primer sequences were obtained from Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea). All other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources.

Phylogenetic tree analysis

The phylogenetic analysis was conducted using 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from NCBI GenBank database. The sequences were aligned using MUSCLE with default parameters to ensure consistency. The alignment was then used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the maximum likelihood method implemented in MEGA11 Program. The General Time Reversible model was applied as the substitution model, selected based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) score. Branch support was assessed using 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Extracellular vesicle isolation

L. gasseri GFC-1220 (GenBank: PP577675.1) was isolated following previously described ultracentrifugation methods56. The strain was cultured in 1 L of MRS broth medium with 10% skim milk (KisanBio, Seoul, Korea). The bacteria culture was grown at 150 rpm and 37 °C for 24 h, reaching the stationary phase with an approximate density of 1 × 1010 CFU/ml. Following that, we removed the bacteria cells via centrifugation at 4000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation (Hitachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan) at 10,000 × g for 30 min, followed by 150,000 × g for 2.5 h at 4 °C. The culture supernatants were then filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA) to eliminate residual bacteria and cellular debris. The resulting pellets were collected and resuspended in distilled water, yielding approximately 9.5 × 1012 particles/L.

Characterization of LEVs

The morphology of LEVs was observed using Cryo-EM. To confirm the diameter and particle concentration of LEVs, NTA was conducted using a Zetaview TWIN (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, DE). The detailed methods and operating conditions for Cryo-EM and NTA are described in a previously published article57. Particularly, Cryo-EM and 2D imaging were conducted using a Talos L120C transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Czech Republic) operated at 120 kV to evaluate the size and morphology of LEVs. For NTA, LEVs were irradiated with a blue-light laser at a wavelength of 488 nm. The sample conductivity was performed at 10.85 µS/cm, and the analysis was conducted at 20.3 °C. Additionally, DLS and zeta potential measurements were performed using a particle size and zetapotential analyzer (ELSZ-2000ZS, Otsuka Electronics, Shiga, Japan). The protein concentration of LEVs, determined using a Bradford assay, was 21.4 µg/mL, complementing the particle concentration of 1.9 × 1012 particles/mL.

Cell viability assay

MTT assay was employed to assess the cytotoxicity of LEVs on RAW264.7 cells. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and allowed to reach 90% confluence. Following this, the cells were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and treated with various concentrations (1, 1.5, 2 × 1010 particles/mL) of LEVs for 24 h. The cells treatment with DEX (1 μM) were used as positive control. MTT assay was performed according to a previously described protocol58.

Live/dead staining

Following the cell treatment procedure detailed above, cells were subjected to staining using the live/dead staining viability kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 30 min of incubation. The stained cells were observed under a fluorescence scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Nitric oxide determination

NO levels were evaluated using the Griess reagent assay. In a 96-well plate, 100 μL of culture supernatant was added to 100 μL of Griess reagent and then incubated for 10 min before measurement at 570 nm using a spectrophotometric microplate reader (Molecular Devices Filter Max F5). A standard curve was generated using sodium nitrite.

ROS and Mito-SOX detection

Intracellular ROS and Mito-SOX levels were measured using a cellular ROS detection kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Initially, cells were treated with LEVs and LPS (1 μg/mL) in a 6-well plate for 24 h. Afterwards, the cells were washed by PBS and stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions, indicating oxidative stress (green) and the superoxide detection reagent (red). Fluorescence was visualized using a laser scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and quantified using Image J.

Enzyme-linked immunoassay

The secretion cytokine levels of PGE2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were determined using ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. 100 μL of cell supernatant was collected for evaluation after LEVs treatment in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells.

Quantitative real-time PCR

We extracted total RNA using a TRIzol reagent kit (Invitrogen). Subsequently, 500 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the amfiRivert cDNA Synthesis Platinum Enzyme Mix (GenDEPOT). For quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis, a Rotor-Gene qRT-PCR machine (QIAGEN, Seoul, Korea) was used in conjunction with the AmfiSure qGreen Q-PCR Master Mix (2 ×) Kit (GenDEPOT) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 20 μL of each qRT-PCR reaction contained of 50 ng of cDNA, and 10 μL of amfiSure qGreen Q-PCR Master Mix. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. To standardize gene expression levels, an endogenous control (GAPDH) was used as a reference. Relative gene expression was analyzed using the formula 2−ΔΔCt.

Investigation of membrane TLR4 receptor

To determine the specific receptor involved in the inhibition of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells via NF-κB pathway, LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells were treated with TLR4 inhibitor – TAK-242 (1 μM), LEVs (2 × 1010 particles/mL), and the positive control – DEX (1 μM). ELISA and qRT-PCR were employed to measure the secretion levels and gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β.

Western blotting

After treating LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells with LEVs, we harvested cell pellets and lysed them in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (GenDEPOT) for 1 h, and subsequently centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. After quantification using the Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng of total protein was loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 5% skimmed milk was used to incubate the membrane for 1 h at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C). Thereafter washing with PBST, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (dilution 1:1000) overnight at 4 °C and further incubation with secondary antibody solution at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 2 h. Protein bands were visualized using West-Q Pico ECL Solution (GenDEPOT) and detected using the Alliance MINI HD9 AUTO Immunoblot Imaging System (UVItec Limited, Cambridge, UK). Subsequent quantification of protein expression levels was performed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in three replicates, with data presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc.). One-way analysis of variance (AVOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range test was used to evaluate statistical differences. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- EVs:

-

Extracellular vesicles

- LEVs:

-

Extracellular vesicles derived from Lactobacillus gasseri

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- DEX:

-

Dexamethasone

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin 6

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin 1-beta

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- iNOS:

-

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase 2

- PGE2 :

-

Prostaglandin E2

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Mito-SOX:

-

Mitochondrial superoxide

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- NTA:

-

Nanoparticles tracking analysis

- Cryo-EM:

-

Cryogenic electron microscopy

- MyD88:

-

Myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- IRAK-4:

-

Interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 4L

- IKK-α:

-

Inhibitory-κB kinase alpha

References

Yáñez-Mó, M. et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 1–60. https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v4.27066 (2015).

Chronopoulos, A. & Kalluri, R. Emerging role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in cancer. Oncogene 39, 6951–6960. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-020-01509-3 (2020).

Hosseini-Giv, N. et al. Bacterial extracellular vesicles and their novel therapeutic applications in health and cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.962216 (2022).

Bilen, M. et al. The contribution of culturomics to the repertoire of isolated human bacterial and archaeal species. Microbiome 6, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0485-5 (2018).

Karaman, I., Pathak, A., Bayik, D. & Watson, D. C. Harnessing bacterial extracellular vesicle immune effects for cancer therapy. Pathog. Immun. 9, 56–90. https://doi.org/10.20411/pai.v9i1.657 (2024).

Dempsey, E. & Corr, S. C. Lactobacillus spp. for gastrointestinal health: Current and future perspectives. Front. Immunol. 13, 840245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.840245 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Unveiling clinical applications of bacterial extracellular vesicles as natural nanomaterials in disease diagnosis and therapeutics. Acta Biomater. 180, 18–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2024.04.022 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Bacterial extracellular vesicles as bioactive nanocarriers for drug delivery: Advances and perspectives. Bioact. Mater. 14, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.12.006 (2022).

Buzas, E. I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00763-8 (2023).

Choi, J. H. et al. Lactobacillus paracasei-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the intestinal inflammatory response by augmenting the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 423–437 (2020).

Kim, M. H. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum-derived extracellular vesicles protect atopic dermatitis induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived extracellular vesicles. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 10, 516–532 (2018).

Selle, K. & Klaenhammer, T. R. Genomic and phenotypic evidence for probiotic influences of Lactobacillus gasseri on human health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 915–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12021 (2013).

Arulselvan, P. et al. Role of antioxidants and natural products in inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 5276130. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5276130 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 9, 7204–7218. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23208 (2018).

Panigrahy, D., Gilligan, M. M., Serhan, C. N. & Kashfi, K. Resolution of inflammation: An organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 227, 107879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107879 (2021).

Lawrence, T. & Gilroy, D. W. Chronic inflammation: A failure of resolution?. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 88, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00507.x (2007).

Oishi, Y. & Manabe, I. Macrophages in inflammation, repair and regeneration. Int. Immunol. 30, 511–528. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxy054 (2018).

Chen, S. et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01452-1 (2023).

Paul, B. Concatenated 16S rRNA sequence analysis improves bacterial taxonomy. F1000Res 11, 1530 (2022).

Kim, W. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum-derived extracellular vesicles induce anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization in vitro. J. Extracell. Vesicles 9, 1793514 (2020).

Lee, E. Y. et al. Gram-positive bacteria produce membrane vesicles: Proteomics-based characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-derived membrane vesicles. Proteomics 9, 5425–5436 (2009).

Xu, X. Y. et al. Whitening and inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammation properties of the biotransformed green ginseng berry of new cultivar K1, ginsenoside Rg2 enriched, on B16 and LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. J. Ginseng Res. 45, 631–641 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Ginsenoside Rh1 potentiates dexamethasone’s anti-inflammatory effects for chronic inflammatory disease by reversing dexamethasone-induced resistance. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, 1–11 (2014).

Chelombitko, M. A. Role of reactive oxygen species in inflammation: A minireview. Moscow Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull. 73, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.3103/S009639251804003X (2018).

Ai, F., Zhao, G., Lv, W., Liu, B. & Lin, J. Dexamethasone induces aberrant macrophage immune function and apoptosis. Oncol. Rep. 43, 427–436 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Anti-inflammatory activities of amber extract in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 2647 macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 141, 111854 (2021).

Turner, M. D., Nedjai, B., Hurst, T. & Pennington, D. J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1843, 2563–2582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014 (2014).

Fitzgerald, K. A. & Kagan, J. C. Toll-like receptors and the control of immunity. Cell 180, 1044–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.041 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Immunoregulatory effects of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum polysaccharide via TLR4-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in Raw2647 macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114471 (2023).

Jeong, D. et al. Visualizing extracellular vesicle biogenesis in gram-positive bacteria using super-resolution microscopy. BMC Biol. 20, 270 (2022).

Liu, Y., Defourny, K. A. Y., Smid, E. J. & Abee, T. Gram-positive bacterial extracellular vesicles and their impact on health and disease. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1502 (2018).

Briaud, P. & Carroll, R. K. Extracellular vesicle biogenesis and functions in gram-positive bacteria. Infect. Immun. 88, e00433-e520. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00433-20 (2020).

Schlatterer, K. et al. The mechanism behind bacterial lipoprotein release: Phenol-soluble modulins mediate toll-like receptor 2 activation via extracellular vesicle release from staphylococcus aureus. MBio 9, 1–13 (2018).

Xie, J., Haesebrouck, F., Van Hoecke, L. & Vandenbroucke, R. E. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: An emerging avenue to tackle diseases. Trends Microbiol. 31, 1206–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2023.05.010 (2023).

Mahmoudi, F., Hanachi, P. & Montaseri, A. Extracellular vesicles of immune cells; immunomodulatory impacts and therapeutic potentials. Clin. Immunol. 248, 109237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2023.109237 (2023).

Gul, L. et al. Extracellular vesicles produced by the human commensal gut bacterium Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron affect host immune pathways in a cell-type specific manner that are altered in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Extracell. Ves. 11, e12189 (2022).

Van Bergenhenegouwen, J. et al. Extracellular vesicles modulate host-microbe responses by altering TLR2 activity and phagocytosis. PLoS ONE 9, e89121 (2014).

Morishita, M. et al. Activation of host immune cells by probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles via TLR2-mediated signaling pathways. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 45, 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b21-00924 (2022).

Rodovalho, V. D. R. et al. Extracellular vesicles produced by the probiotic Propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 mitigate inflammation by modulating the NF-κB pathway. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1544. (2020).

Kang, E. A. et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from kefir grain Lactobacillus ameliorate intestinal inflammation via regulation of proinflammatory pathway and tight junction integrity. Biomedicines 8, 1–11 (2020).

Hao, H. et al. Effect of extracellular vesicles derived from Lactobacillus plantarum Q7 on gut microbiota and ulcerative colitis in mice. Front Immunol 12, 777147 (2021).

Murakami, M. & Hirano, T. The molecular mechanisms of chronic inflammation development. Front. Immunol. 3, 323. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00323 (2012).

Tansey, M. G. et al. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00684-6 (2022).

Montazersaheb, S. et al. COVID-19 infection: An overview on cytokine storm and related interventions. Virol. J. 19, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01814-1 (2022).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 (2010).

Duque, G. A. & Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 5, 491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491 (2014).

Chelombitko, M. A. Role of reactive oxygen species in inflammation: A minireview. Moscow Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull 73, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.3103/S009639251804003X (2018).

Tavassolifar, M. J., Vodjgani, M., Salehi, Z. & Izad, M. The influence of reactive oxygen species in the immune system and pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Autoimmune Dis. 2020, 5793817. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5793817 (2020).

Muniandy, K. et al. Suppression of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators in LPS-Induced RAW 2647 macrophages by stem extract of Alternanthera sessilis via the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 3430684 (2018).

Oh, N. S., Joung, J. Y., Lee, J. Y. & Kim, Y. Probiotic and anti-inflammatory potential of Lactobacillus rhamnosus 4B15 and Lactobacillus gasseri 4M13 isolated from infant feces. PLoS ONE 13, e0192021 (2018).

Manoharan, R. R., Prasad, A., Pospíšil, P. & Kzhyshkowska, J. ROS signaling in innate immunity via oxidative protein modifications. Front. Immunol. 15, 1359600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1359600 (2024).

Mucha, P., Skoczyńska, A., Małecka, M., Hikisz, P. & Budzisz, E. Overview of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of selected plant compounds and their metal ions complexes. Molecules 26, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164886 (2021).

Jiang, S. et al. The activation effects of fucoidan from sea cucumber Stichopus chloronotus on RAW264.7 cells via TLR2/4-NF-κB pathway and its structure–activity relationship. Carbohydr. Polym. 270, 118353 (2021).

Karunarathne, W. A. H. M., Lee, K. T., Choi, Y. H., Jin, C. Y. & Kim, G. Y. Anthocyanins isolated from Hibiscus syriacus L. attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and endotoxic shock by inhibiting the TLR4/MD2-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 76, 153237 (2020).

Qiao, Y. et al. Small RNAs in Plant Immunity and Virulence of Filamentous Pathogens. Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS (2021) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-121520

Jo, C. S. et al. The effect of Lactobacillus plantarum extracellular vesicles from Korean women in their 20s on skin aging. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 44, 526–540 (2022).

Yoon, Y. C. et al. Stimulatory effects of extracellular vesicles derived from Leuconostoc holzapfelii that exists in human scalp on hair growth in human follicle dermal papilla cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 44, 845–866 (2022).

Mi, X. J. et al. The immune-enhancing properties of hwanglyeonhaedok-tang-mediated biosynthesized gold nanoparticles in macrophages and splenocytes. Int. J. Nanomed. 17, 477–494 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by KDBIO Corp., the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF, 2023R1A2C1007606) and Kyung Hee University under the project (KHU-20202298).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAK and MHL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. HJL and JWM carried out the experiments. MJK and HCK analyzed the results. YJK edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koh, JA., Le, M.H., Lee, HJ. et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from Lactobacillus gasseri GFC-1220 alleviate inflammation via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Sci Rep 15, 21381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99160-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99160-z