Abstract

As oil reservoir pressure diminishes with production, technology for efficient oil recovery becomes imperative. Water flooding emerges as a proven method to restore reservoir pressure, emphasizing the critical role of water composition. This study explores the ionic impact of engineered water on oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs. Through contact angle, interfacial tension, and core flooding experiments, seawater with double sulfate ion concentration (SW2S) performs best, altering wettability and reducing IFT via sulfate-driven ionic interactions. SW2S caused the IFT to change by -5.63, altered the contact angle by 65.72, and increased oil recovery with the added benefit of promoting emulsion formation, particularly in the S-1 crude oil system, where it achieved the oil recovery by 10.27%. Results reveal the influence of crude oil components on water composition effectiveness, with resin and asphaltene playing key roles. The study emphasizes considering crude oil characteristics when selecting optimal water compositions, proposing a combination of sulfate, magnesium, and calcium ions to enhance oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs. This research provides crucial insights into the ionic effects of engineered water, emphasizing the significance of reservoir and crude oil specifics in water composition optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As oil reservoir pressure decreases and production declines substantially, most oil will be trapped underground (about 85% of the original oil in place)1. Therefore, methods must be used to enhance oil production from depleted reservoirs by producing residual oil. Water flooding is the most popular and well-studied technique for increasing oil recovery efficiency2,3.

The effectiveness of engineered water in enhancing oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs hinges on two primary mechanisms: wettability alteration and interfacial tension (IFT) reduction. Carbonate rocks are often oil-wet due to the adsorption of polar oil components, such as carboxylic acids, onto the positively charged rock surface4. Wettability alteration shifts this state toward water-wetness by enabling specific ions, like sulfate, to adsorb onto the rock, displacing these oil components and promoting water displacement of oil2. Simultaneously, IFT reduction lowers the capillary forces trapping oil by altering the oil-water interface through ionic interactions with polar oil constituents, such as resins and asphaltenes5,6. Additionally, engineered water, particularly low salinity water, can facilitate emulsions’ formation, further enhancing oil recovery by improving sweep efficiency7,8. These mechanisms are critical for optimizing water composition to improve recovery efficiency2,9,10.

The water flooding technique could be enhanced by modifying the salt concentrations by manipulating viscous forces, fluid/fluid interactions (IFT), and fluid/solids interactions (wettability) to modify the mobility ratio during the fluid injection process11,12. Previous investigations revealed that higher oil recovery efficiency can be achieved if the ion concentration presented in the injection water is manipulated13. This type of saline water, which is commonly known as Engineered Water (EW), is recently gaining attention as a new and efficient EOR technique; it consists of two types of saline water, which are called Low Salinity Water (LSW) and Smart Water (SmW)14,15. The popularity of this technique comes from several unique advantages, including the efficiency of displacing light to medium gravity crude oils, ease of injection into oil-bearing formation, water availability and affordability, being environmentally friendly, no expensive chemicals added, low damage problems and lower capital and operating costs for the fields already treated by the water flooding process14,16,17,18.

The literature proposes various mechanisms to explain the additional oil recovery from LSWI/SmW injection. The researchers’ significant mechanisms include interfacial tension reduction and wettability alteration9,10,19. These mechanisms explain the improvement in oil recovery resulting from the rock’s wettability changing from a mixed-wet state to a more water-wet condition.

Although LSW/SmW injection has received growing attention over recent years, the effect of LSW/SmW injection on carbonate rock has not been systematically investigated compared to sandstones20,9. Previously performed investigations revealed that most carbonate reservoirs are between neutral and oil-wet states due to the natural surfactants’ adsorption in the crude oil. On the other hand, since more than half of the world’s proven hydrocarbon reserves are stored in carbonate reservoirs, it is necessary to systematically investigate the effect of LSW/SmW injection on the oil recovery of these specific reservoirs21,22,23.

Interfacial tension (IFT) measurements for LSW/SmW injection were made by numerous studies, which found that the reduction of the IFT was too small to impact oil recovery. The results showed that LSW/SmW injection impacts the Contact Angle (CA) more than IFT. More impact on CA than IFT implies that diluted Seawater (SW) influences rock/oil/brine rather than oil/brine interactions. In some cases, even the reverse effect of LSW on IFT was observed24,25,26. An increase in IFT with decreasing salinity was reported by Alameri et al. (2014), in contradiction with the improvement of oil recovery by the low salinity effect. According to recent research, altering the qualitative characteristics of an oil-water interface could be more important than merely changing the interfacial tension27,28. The interface can be viscous, liquid-like, elastic, or solid-like, depending on the compositions of the contacting fluids. Intermediate states are also possible. This effect has been known for at least 60 years for oil-brine contacts29. It was attributed to surface-active compounds in the oil, particularly asphaltenes28,30.

Recently, it has been realized that IFT reduction is vital for LSW/SmW injection. If an oil-brine interface becomes solid-like, oil separates more easily from the rock surface. On the contrary, if the interface is liquid-like, separate oil drops can coalesce and form a continuous flowing oil phase. The ions that make the oil-water interface more elastic should concentrate close to the rock surface in the ideal brine recipe, while the ions that make the interface more viscous should remain in the solution. Notably, the presence of sulfates in a brine sometimes promotes the hardening of the interface27.

The wettability of any rock can be reversed toward being oil-wet to release oil capillary trapping or toward being water-wet to enhance water imbibition and oil counter-current production. Cassie and Baxter, Buckley et al.31, Furthermore, Chen et al.32 indicated that the water film separating crude oil from the mineral surface is not always stable and that the original water wetness of the rock can be altered by destabilizing the water film. Consequently, changing the wettability must overcome the disjoining pressure to destabilize and break the water film. Zhang et al.4 examined the role of divalent cations, namely, calcium, magnesium, and sulfate ions, on wettability alteration in carbonates. The ratio of Ca2+/SO42−was found to have a more pronounced effect on wettability alteration and recovery than monovalent anions33,34,35.

Although the majority of researchers proposed a change in wettability as the governing mechanism in carbonates during the LSW/SmW injection, IFT reduction between two phases has also been checked by some researchers25,36,37,38. Several factors affect IFT, like injection brine components, salt concentration, temperature, pressure, pH, etc. According to the literature reviews, pressure and temperature have the most negligible effects on IFT reduction, and the most important factors on IFT reduction are injection brine components and salt concentration21,39,40, which are investigated in this study. Some of the mentioned studies show disagreements and conflict in IFT analysis and the governing mechanisms. Taking into account all of these contradicting results, in this study, the effect of different types of injection water on the surface properties of liquid-liquid (IFT) and liquid-rock (CA) due to the presence of polar compounds using five different types of crude oil from one of the oil field in the south of Iran (OFSI) were examined systematically. For designing injection water with a constant value of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) equal to seawater, several analyses have been performed using OLI ScaleChem software.

Additionally, experimental and simulation compatibility analysis is done for all types of injection water. PHREEQC software chooses the optimal injection water with a minimum potential for mineral scale precipitation. After designing and selecting the most effective injection water and conducting IFT and CA experimental tests, core flooding tests were performed for injection water with the best performance in IFT and CA experimental tests. Finally, the superior injection water with the highest oil recovery is chosen for each formation.

Methodology

Brine

This study chose two types of water as injection fluids to investigate their impact on oil recovery. The first injection fluid category was low-salinity water. The experiments considered Persian Gulf seawater (SW), which has a total salinity of 40,572 ppm, and three other low-salinity waters. The compositions of the different types of injection water used in this study are given in Table 1.

Second, injection water with an equal salinity of SW was used as smart water in the experimental tests. The SmW was named SW(x)Ca(y)Mg(z)S, where (x), (y), and (z) represent the concentration order of Ca2+, Mg2+, and SO42− respectively, instead of SW. For example, SW2 Ca indicates a double concentration of Ca2+ in the modified seawater compared to the SW at the constant concentrations of Mg2+ and SO42−. Mg2+ and SO42− concentrations are zero in SW0Mg0S, but the concentration of Ca2+ remains constant in SW. Table 2 lists the composition of all SmW used, and Fig. 1 shows its image.

Crude oil

A crude oil sample from five formations of OFSI was employed in this investigation. The oil sample was first centrifuged and filtered through 5 mm filter paper to remove solid particles, dissolved gases, and water. Table 3 provides SARA analysis for different oil samples. Also, the Component characterization and physical properties of crude oil samples are shown in Supplementary Tables S-1 and S-2.

Cores

Two cores were utilized for core flooding tests. XRD analysis revealed that they comprised 96% CaMg(CO3)2, 1.5% CaCO3, and 1% SiO2, indicating that the cores were carbonate rocks. The characteristics of the cores are presented in Supplementary Table S-3. Also, Carbonate core samples from a single reservoir were used for consistency in rock properties, while crude oils from five formations (G-1, S-1, K-1, F-1, F-2) were evaluated for IFT and contact angle. Core flooding experiments focused on three oils (S-1, K-1, F-1) to assess recovery under representative conditions.

Apparatus

Drop shape analysis (DSA) apparatus

This study used a drop shape analysis apparatus (DSA) based on the pendant drop technique to determine the IFT between crude oil and brine. The DSA technique is probably the most advanced and accurate method for measuring the IFT, especially for the IFT range of 3–80 mN/m. Compared to the other existing methods, the DSA technique for the pendant drop case is accurate for the IFT measurement (0.05 mN/m), fully automatic, and completely free of the operator’s subjectivity41,42. Therefore, this technique has been widely proposed as a standard method for measuring the IFT43. In the case of IFT measurements, a precise interfacial tension measurement is achievable with the help of a computer-controlled IFT measuring device outfitted with image analysis software.

Contact angle measurement (CA) apparatus

An oil droplet was placed on the carbonate’s thin-section surface to measure the contact angle. The droplet was allowed to equilibrate for one day before measurements were taken. The droplet images were taken using a high-resolution camera, and contact angles were calculated and analyzed using ImageJ software.

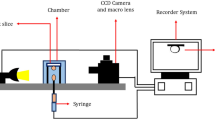

Core flooding apparatus

The core flooding apparatus used in this research is designed to conduct experiments under high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT), or ambient conditions to evaluate oil recovery using waterflooding or any other type of injection. Pressure transducers that monitor absolute and differential pressure record the system pressure through data gathering.

Experimental test procedure

Experimental tests were divided into several stages to investigate the effect of LSW/SmW injection on improving oil production and reducing residual oil: solutions preparation, compatibility analysis, IFT analysis, contact angle measurements, and core flooding tests.

Solution Preparation

Different LSW/SmW were initially designed and chosen based on published literature in the same fields in Iran or worldwide. For LSW solutions, the Persian SW was diluted 5, 20, and 40 times, as detailed in Table 1. Also, all SmWs were prepared by dissolving a specific concentration of different salts in deionized water (DIW). Noteworthy is the fact that OLI ScaleChem software is used to calculate and maintain a charge balance between ions in solutions. The salts (NaCl, KCl, MgCl2.6H2O, CaCl2.2H2O, NaHCO3, Na2SO4) were all purchased with a purity of 99% from Merk Co. To prevent the precipitation of salts through the water synthesis process, they should be added in a successive order of CaCl2, MgCl2, KCl, NaCl, Na2SO4, and NaHCO3. The ionic compositions of 15 types of SmW considered for experiments in the research are listed in Table 2. The amount of different salts used for preparing various injection solutions is detailed in Supplementary Table S-4.

Compatibility analysis

After designing the solutions, their compatibility with formation water (FW) was analyzed. Since formation water contains a high concentration of divalent cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, and Sr2+) and SW’s sulfate concentration is too high, precipitation is probable for inorganic minerals (SrSO4, CaSO4)44. In this regard, PHEERQC software was employed to simulate injection solution mixing at various ratios. This step was performed to screen the designed fluid.

IFT measurement

Interfacial tension is the force that exists between two dissimilar phases, such as a gas-liquid, gas-solid, liquid-liquid, or liquid-solid interface. As a result of the molecules in the substance, whether solid or liquid, having the same kind as their neighbors, they are drawn equally in every direction, resulting in zero net force. It is a different situation at the interface. Through cohesive forces, the molecules will interact with similar molecules they see below and on their sides. These cohesive forces can be powerful in air-liquid systems, especially in air-solid systems, resulting in high surface tension and free energy values. However, the adhesive forces between the dissimilar molecules also matter and balance the forces at the interface when two immiscible liquids, liquid and solid, come into contact.

Interfacial tension (IFT) measurement is essential to identify suitable injection water solutions with the effect of desirable selective ions on reducing surface tension. Due to the tendency of small drops to be spherical, the IFT between different types of LSW/SmW and crude oil was measured based on the drop shape by the pendant drop method. When a drop starts to form, the camera captures a video until the drop is entirely detached from the needle, and the last image before detachment is used for IFT measurement. Each experiment was conducted four times to verify the accuracy of the data. Also, to obtain a constant coefficient for measuring IFT, the density of the injection water was measured, and the density difference with crude oil from various formations was multiplied by gravity drainage. These coefficients are listed in Supplementary Table S-5.

Contact angle measurements

Many methods are used to determine wettability, such as contact angle measurement (sessile drop method), the Amott-Harvey test, and USBM (centrifuge method). However, the method that is often used to determine the wettability of a water-oil system is contact angle measurement. In this technique, a drop of water is placed on a mineral surface where reservoir oil is present, and based on the shape and dimensions of the drop, the degree of wettability and the contact angle are ascertained.

The CA is the angle conventionally measured through the denser liquid, where a liquid-vapor interface meets a solid surface. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation. A unique equilibrium contact angle exists for a given system of solids, liquids, and vapors at a given pressure and temperature. In actuality, though, contact angle hysteresis is frequently seen as a dynamic phenomenon that ranges from the receding (minimal) to the advancing (maximal) contact angle. These values can be used to calculate the equilibrium contact contained within them. The equilibrium contact angle indicates the strength of the molecular interactions between liquid, solid, and vapor. If the contact angle is between 0° and 90°, the system is water-wet (hydrophilic), while if this angle is equal to 90°, the system is intermediate-wet. For the values greater than 90°, the system becomes oil-wet (hydrophobic).

Wettability alteration is one of the primary EOR mechanisms used in LSW/SmW injection. Several contact angle tests were conducted in this study to examine the crucial function of the wettability change of LSW/SmW injection. Figure 2 shows thin sections of a rock sample from the OFSI oil fields (F-1, F-2, K-1, S-1, and G-1) aged with crude oil from the reservoirs for a month to conduct contact angle tests. The interaction between fluid/rock was tested for all prepared fluids. A drop was settled on the thin section’s surface, and 24 h were used to measure the drop’s contact angle. The best injection solution could change the contact angle more than others and change the wettability to more mixed-wet or water-wet conditions.

Core flooding tests

A core flooding study examined how altering the salinity and ionic composition of the injection water affects oil recovery. The experimental parameters and procedures were well designed to reflect the initial conditions usually found in carbonate reservoirs and current field injection practices.

The core flooding process was conducted after measuring the initial properties of clean, dry cores. The following experimental procedure is described below:

-

1.

The cores were cleaned with toluene and dried in an oven for 24 h. A vacuum pump suctioned each clean core sample for an hour.

-

2.

A confining pressure 400 psi higher than the injection pressure was applied.

-

3.

Injection FW completely saturated the cores at an injection rate of 0.3 mL/min.

-

4.

The pressure difference along the core was measured at three injection rates: 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mL/min. Then, using Darcy’s law, the permeability was determined.

-

5.

The saturated core with FW was allowed to age for two days, and then its weight was measured to indicate its pore volume and porosity.

-

6.

Filtered crude oil was injected into the core samples at 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 mL/min to ensure the cores were entirely at their initial water saturation (Swi) state.

-

7.

Oil relative permeability was calculated based on the pressure difference along the core.

-

8.

One week of aging was applied at 80 degrees Celsius to restore the cores’ wettability.

-

9.

4 PV oils are injected to mimic oil-saturated reservoir conditions.

-

10.

FW was injected to displace the oil at 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 mL/min flow rate (for 10 PV). Oil recovery during waterflooding and water relative permeability were determined.

-

11.

SW was injected using the same procedure as FW.

-

12.

EWs were injected to investigate the effect of LSW/SmW on incremental oil recovery and wettability alteration. Oil production, flow rate, and pressure drop were recorded and analyzed during the core flooding experiment.

Result and discussion

Compatibility study

LSW/SmW injection has many advantages and is more economical than other methods, but it could cause some problems and formation damage5,45,46,47,48,49,50. Besides, due to the high reactivity of carbonate rocks with chemical fluid in the water phase and active ions, some issues may occur during water flooding51,52,53,54,55,56.

LSW/SmW contains different salts, and mixing with FW causes some incompatibilities57. For example, there is a high SO42− concentration in SW, whereas FW has a high concentration of divalent cations, like Ca2+ and Sr2+. As a result, when injection fluids from SW and FW are mixed, insoluble scales precipitate (e.g., CaSO4 and SrSO4)58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65.

The generation of inorganic scales lowers the reservoir productivity index (PI) and the permeability of the porous media. Also, the precipitation of inorganic scales can restrict and clog downhole or wellhead facilities. Research has been conducted to eliminate metal-containing precipitation from water, which entails significant costs and time66,67,68,69,70. Therefore, when engineers choose to run the water flooding process, they must pay close attention to the FW and SW and their ionic composition. In addition to IFT measurements, the compatibility of injection water was examined in this research when mixed with FW. Since the connate water saturation of the petroleum reservoirs is about 20%, the compatibility study was done at an injection water ratio of 80%.

The PHREEQC software was used to simulate mixing FW with various types of injection water to form mineral scales. Data such as pH, temperature, pressure, and brine ionic compositions should be inputted to the PHREEQC for modeling. Each injection water (LSW/SmW) was simulated in ambient and reservoir conditions.

According to the outcomes of the PHREEQC software, most of the minerals created at ambient conditions are related to FW. 73% of the material created was Celestite with a value of 210.5 mg/l, and 27% was Calcite with 76.63 mg/l. The next multi-scale water that formed different mineral scales is SW4 Ca, and the total scale includes very close amounts of Gypsum and Dolomite. In two types of injection water, which include SW0Mg and SW0Mg0S, the total quantity of mineral scale equals Calcite. However, Dolomite was only formed for the remaining injection water.

The simulation results with PHREEQC software at a temperature of 140 degrees Celsius, and a pressure of 4500 psi showed that most of the minerals formed are related to SW4 Ca. The minerals formed were 92% anhydrite, with a value of 2703.7 mg/l, and 8% Calcite, with a value of 250.6 mg/l. In this condition, the total quantity of mineral scale equals Calcite for 5DSW, SW0S, and SW0Mg0S. In addition, just Dolomite was formed for SW, SW2Mg, SW3Mg, and SW4Mg.

In the next step, various kinds of injection and formation water were combined under ambient and reservoir conditions (Figs. 3 and 4). The simulation results for mixing formation water and injected water at ambient and reservoir conditions showed that the quantity of mineral scale was higher in reservoir conditions60,71. The highest amount of total minerals formed is related to mixing 40% of formation water with 60% of SW4S. After SW4S, SW3S and SW2S have more mineral scale deposition than other injection water.

The saturation index for each scale (SrSO4, for example) was provided following computations. Inorganic mineral scales have a thermodynamic tendency to form when each mineral’s saturation index is more than zero. Additionally, to the saturation index, PHREEQC could calculate the amount of each scale28. Table 4 demonstrates the amount of inorganic precipitation when various injection fluids were mixed with FW.

Table 4 provides critical insights into the potential for inorganic scale formation, a key operational challenge in waterflooding processes. When injection fluids mix with the formation water in a reservoir, differences in ionic compositions can trigger the precipitation of sparingly soluble minerals, such as calcium sulfate (CaSO4) and strontium sulfate (SrSO4). This scaling can clog pore spaces, reduce permeability, and impair injectivity, ultimately compromising the efficiency of waterflooding and EOR. The table evaluates two categories of injection fluids:

1) low salinity water (LSW): variants of diluted seawater (SW, 5DSW, 20DSW, 40DSW)

2) smart water (SmW): seawater modified with adjusted ion concentrations (SW2S, SW4S, SW0S, SW2 Ca, SW4 Ca)

The 80:20 mixing ratio reflects a realistic scenario where injection water dominates but still interacts with residual FW, making the data highly relevant for predicting scaling risks under typical reservoir conditions.

When injection water and FW share ions that form low-solubility compounds (Ca2+ and SO42−), their combined concentrations can exceed the solubility product, leading to precipitation. Seawater (SW) contains high SO42− (3209 ppm), while FW is rich in Ca2+ (7615.2 ppm) and Sr2+ (1581.9 ppm). Mixing these fluids can precipitate CaSO4 and SrSO4. In summary, the results of the table reveal that mixing injection fluids with FW at an 80:20 ratio can lead to significant inorganic precipitation, with sulfate-rich smart waters (SW4S: 5.729 g/l) posing the greatest scaling risk due to CaSO4 and SrSO4 formation. In contrast, highly diluted LSW (20DSW: 0.005 g/l) nearly eliminates scaling by reducing ionic concentrations. The common ion effect and supersaturation drive these outcomes, with sulfate playing a pivotal role. While SW2S offers EOR advantages, which will be discussed in the results and discussion of the core flooding section, its scaling potential (2.302 g/l) underscores the need for a balanced approach, integrating recovery optimization with scale mitigation to ensure operational success in waterflooding projects.

IFT analysis

The tension that exists between two distinct liquids is known as interfacial tension. Higher interfacial tension means that both liquids tend to separate into two phases. As the two fluids’ respective densities get closer to one another, the IFT will decrease. If the IFT is zero, the forces between the fluids are balanced so that these fluids combine to form a single miscible fluid. Thus, reducing the interfacial tension is essential to creating a stable emulsion and enhancing oil recovery72. In this investigation, the IFT between oil samples is measured and analyzed using twenty types of injection water. The IFT reduction is calculated from Eq. 1.

∆IFT = IFToil/SmW - IFToil/SW (1).

Based on the results obtained for the G-1 crude oil (Fig. 5), reducing the salinity of injection water plays an influential role in interfacial tension reduction because at low salinity of injecting water, the solubility of organic material (asphaltene and resin) is greater than that of water solution with high salinity and this results in better IFT reduction at lower concentration of injecting water (salting-in effect)6 Among low salinity water, the best performance is forty times diluted seawater (40DSW). However, in the injection of smart water, no specific trend is observed for calcium and magnesium ions, and their best performance is observed at two- and a three-times excess amount of ions, respectively. However, increasing sulfate ion concentration will decrease IFT. In the following, the same behavior was observed for brine-containing single potential determining ion (PDI). As shown in Fig. 6, Regarding interfacial tension measurements and their decrease, SW2 Ca, SW3Mg, and SW0 Ca0Mg injecting water have demonstrated the best performance in the G-1 formation overall.

According to Fig. 7, for the S-1 crude oil, the amount of IFT increases as the injection water salinity decreases. Thus, five times diluted seawater (5DSW) has the highest IFT reduction. Some researchers claimed that the high affinity of the divalent cation to the oxygen in the resin structure mitigated the salting-out effect, preventing IFT reduction, based on results from IR (Infrared) spectroscopy at high divalent ion concentrations6. Moreover, other researchers stated that the mechanism behind this behavior might be the tendency of salt ions to migrate to the oil-water interface (at low concentrations) and consequently break down the hydrogen bond between water molecules or move back to the bulk of the brine (at high concentrations)7. The best IFT reduction can be obtained except for sulfate at the minimum concentration of ions. Compared to magnesium and calcium, sulfate ions are crucial in lowering IFT73; this behavior can be confirmed by injection of water with individual PDIs in which SW0 Ca0Mg, which contains only sulfate ions, has the best IFT reduction in comparison with two other brines. According to Supplementary Figure S-1, SW0 Ca, SW0Mg, SW2S, and SW0 Ca0Mg are the best water-injection systems for reducing the IFT of the S-1 formation.

The significant reduction in IFT observed with SW2S (for S-1 crude oil, a decrease of 5.18 mN/m) highlights the role of sulfate ions in altering the oil-water interface. Due to their high charge density, sulfate ions likely interact with the polar fractions of crude oil, specifically resins and asphaltenes, which are abundant in S-1 (13.9 wt% asphaltene, 15.5 wt% resin). These interactions may involve coordination or complexation with polar molecules, reorienting them at the interface and stabilizing them, which reduces IFT. This effect is less pronounced in oils with lower polar content, such as F-1, which will be discussed later (0.5 wt% asphaltene, 4.0 wt% resin), where IFT reduction was minimal (0.21 mN/m). This oil-specific response underscores how crude oil composition influences the efficacy of engineered water in EOR.

As shown in Fig. 8, for the K-1 crude oil formation, the least amount of IFT is obtained at an optimum salinity. For water with low salinity, five times diluted seawater (5DSW) performs better IFT reduction compared with two other low salinity waters. The optimum IFT decrease for the K-1 formation in smart water is achieved by brine, which has three times the excess amount of magnesium ions and twice the excess amount of calcium and sulfate ions compared to the concentration of seawater. Also, the sulfate ion, in comparison with other PDIs, has shown a more influential contribution to lowering IFT and has reduced the amount of IFT even up to 5.94 mN/m, which can be observed in the results of injection water containing individual PDIs because SW0 Ca0Mg has shown better performance compared to other brine. Based on the results, for the K-1 formation, all injection water has shown positive performance in reducing IFT. As can be seen in Supplementary Figure S-2, SW0 Ca0Mg, 5DSW, SW2S, SW2 Ca, and SW3Mg have shown the best performance in reducing IFT, respectively.

Figure 9 illustrates that, except for injecting water containing magnesium, there is an ideal concentration of salts at the injection of low salinity and smart water for the F-1 formation, which results in the greatest decrease in interfacial tension measurements. These optimal concentrations are 20DSW, SW3 Ca, and SW3S. Calcium ions have played an important role in lowering IFT compared to two other PDIs, and magnesium has the weakest performance in reducing IFT. As observed in the results of brine containing individual PDIs, SW0Mg0S possesses the lowest IFT compared to other brine. Based on Supplementary Figure S-3, the best-selected injection waters for the F-1 formation are SW0Mg, 20DSW, SW3 Ca, and SW3S.

According to Fig. 10for the F-2 crude oil, there is a direct relationship between reducing injection water salinity and interfacial tension74. Therefore, according to the results of IFT measurements, a low salinity water injection method is not recommended for the F-2 formation. IFT is not considerably decreased for smart water injection by raising the PDI concentration. In addition, the effectiveness of calcium ions is higher in lowering the tension between surfaces compared to magnesium ions in this formation. Therefore, the best performance among PDIs is the role of the sulfate ion, and the weakest performance corresponds to the magnesium ion, which can be seen in the results of brine containing only one PDI. In summary, according to Supplementary Figure S-4, the best-selected brine are SW0 Ca, SW0Mg, and SW4S, respectively.

To sum up, in this study, LSW has no positive effect on IFT reduction in crude oils containing resin particles.

A closer examination of the findings showed that the IFT of crude oil was reduced because of divalent ions6,75. This observed trend is related to the fact that polar organic components of asphaltene and resin react with the divalent cations (Mg2+ and Ca2+)6,75 and consequently produce complex ions (especially if they are bound to the Cl−anions), which are easily soluble in the phase of water and resulted in IFT reduction76,77. Thus, divalent cations are much more effective in reducing IFT than monovalent cations6,75,78,79.

Moreover, among divalent cations, Mg2+ ions are more likely to reduce IFT than Ca2+ions6. This behavior was observed in Mg2+ compared to Ca2+, which causes the charge density to increase and the affinity of Mg2+ toward oxygen (found in crude oil) than Ca2+76. This information was taken from Mendeleev’s periodic table. Therefore, magnesium can coordinate the oxygen compounds in the resin structure of crude oil because it is the central atom. Compared to Ca2+, Mg2+had a more favorable chemical interaction with the crude oil surface-active agent and a greater influence on IFT reduction6,78,39.

According to Table 3, the F-2 oil sample has a high percentage of resin particles; therefore, diluted SW causes an increase in IFT between oil and brines. Besides, presenting resins in oils influences the effectiveness of different PDIs80,81. Figures 9 and 10 show that Ca2+ and Mg2+ raise the interaction forces between oil and injection solutions. However, Sulfate anions could change the IFT between crude oil and brines positively, and they could obtain less IFT. The F-2 oil sample has 12.5% wt% resin particles, with the lowest IFT with SW4S and SW3S.

Results indicate that oil-containing resin and asphaltene have more IFT reduction than other samples80,81. Comparing the results in Fig. 7with other formations’ IFT demonstrates that S-1 IFT with various SmW is the lowest. This phenomenon is because of the high polar organic component (POC) concentration in the S-1 formation. POC behave like surfactants and adhere to the interface between two immiscible fluids76,81. Consequently, the miscibility of the two fluids increases, and the IFT between them decreases82.

Looking precisely at the IFT results, it was illustrated that presenting asphaltene in crude oils affects Mg2+ and Ca2+ions83. The injection brine with only Ca (SW0S0Mg) significantly reduces IFT for oil containing the least asphaltene. The F-1oil sample has 0.5 wt% asphaltenes and has less IFT with SW0S0Mg than SW0 Ca0S.

Contact angle analysis

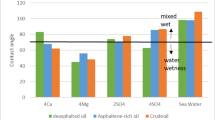

The liquid’s free surface and the liquid’s and solid’s properties in contact determine the contact angle84. How the solid is angled to the liquid’s surface is irrelevant. It changes with surface tension and hence with the purity of the liquid84. Other factors also affect the contact angle, like temperature, pH, pressure, and aging time, but the most crucial factor is the effect of the injection water component85. Therefore, this study has attempted to investigate the key role of brine component injection while other influencing factors are assumed constant. Figures 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16 display the oil droplet’s contact angle in various LSW/SmW presence.

It could be concluded from the contact angle results of the G-1 formation (Fig. 11) that decreasing the salinity of seawater has a positive role in wettability alteration toward water-wetness83, as can be observed, forty times diluted seawater (40DSW) has better performance in decreasing contact angle.

Additionally, based on the results, magnesium and calcium ions have optimum concentrations for reaching the minimum value of contact angle, which is SW2 Ca and SW2Mg, respectively. However, by enhancing sulfate ions from injection water, better performance could be achieved, as SW2S, with a value of 88.4 degrees, has the best wettability alteration, which can demonstrate the essential role of magnesium and calcium PDIs when they are acting together86.

The optimum contact angle decrease for individual PDIs was demonstrated by SW0 Ca0Mg and SW0 Ca0S, indicating that sulfate and magnesium ions may each result in an appropriate adjustment in wettability. Finally, the great wettability alteration can be obtained from SW2 Ca, SW0S, SW0 Ca0S, SW0 Ca0Mg, 40DSW, and SW2Mg for the G-1 formation (Fig. 12).

Figure 13 shows the K-1 formation contact angle results; LSW does not significantly affect wettability alteration or hydrophilicity. However, for SmW, the most effective way to reduce the contact angle has been demonstrated by water containing sulfate ions, particularly at two times the excess sulfate. Magnesium and calcium ions were placed in second and third, respectively.

Effect of (a) low salinity brine, (b, c, d) symbiotic behavior of PDIs, and (e) individual PDI, Ca2+, \(\:{\text{S}\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\), Mg2+ on static contact angle alteration of oil-wet thin section, illustrated on the third day for K-1 formation.

Removing the calcium ions significantly reduces the contact angle (due to the simultaneous action of sulfate and magnesium ions86. In injection water with individual PDIs, sulfate ions decrease the contact angle. In general, according to Supplementary Figure S-5, SW2S, SW3Mg, SW0 Ca0Mg, SW0 Ca, and 40DSW perform best in altering the wettability of carbonate surfaces and directing them towards hydrophilicity, respectively.

Five times diluted seawater (5DSW) is the best salinity concentration for the F-1 formation (Fig. 14), at which the lowest degree of contact angle can be produced. A similar trend is observed for PDIs of sulfate and calcium, both of which have shown the best performance in diminishing the contact angle. Nevertheless, for magnesium ions, four times the excess amount of this ion relative to the seawater has the smallest angle of contact. Examining the results of individual PDIs indicates that compared with other PDIs, calcium ions have the best effect in changing wettability to hydrophilicity.

Effect of (a) low salinity brine, (b, c, d) symbiotic behavior of PDIs, and (e) individual PDI, Ca2+, \(\:{\text{S}\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\), Mg2+ on static contact angle alteration of oil-wet thin section, illustrated on the third day for F-1 formation.

According to Supplementary Figure S-6, the injection water with the best performance in wettability alteration of the F-1 formation are SW2S, SW2 Ca, SW0Mg0S, 5DSW, and SW4Mg, respectively.

Based on the contact angle results for the F-2 formation (Fig. 15), there is an optimal salinity concentration where the lowest contact degree can be obtained, twenty times diluted seawater (5DSW), where the contact angle is reduced to 95.3 degrees. Moreover, sulfate ions exhibit the best circumstances for decreasing the contact angle; SW2S yields the lowest contact angle. However, for magnesium and calcium ions, the contact angle decreases with the increase and decrease of the ions’ concentration, respectively. Furthermore, the best way to reduce the angle of contact in F-2 formation was to inject water with specific PDIs of SW0Mg0S, SW0 Ca0S, and SW0 Ca0Mg, indicating that the cations calcium and magnesium are crucial in modifying the F-2 formation’s wettability.

Effect of (a) low salinity brine, (b, c, d) symbiotic behavior of PDIs, and (e) individual PDI, Ca2+, \(\:{\text{S}\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\), Mg2+ on static contact angle alteration of oil-wet thin section, illustrated on the third day for F-2 formation.

As shown in Supplementary Figure S-7, SW2S, SW4 Ca, 20DSW, and SW0Mg0S decrease the contact angle of the F-2 formation most effectively.

Like most formations, in the S-1 formation, the reduction of injected water salinity positively affects the measurement of the contact angle results. As shown in Fig. 16, there is also an optimal concentration of sulfate and magnesium ions at which the lowest degree of contact angle can be obtained. These optimal concentrations are two- and three-times excess amounts of sulfate and magnesium ions relative to seawater concentration. In addition, sulfate, compared to magnesium, has shown a more effective role in changing wettability toward water wetness83. However, calcium ions have no specific trend. However, the minimal contact angle is observed at four times the excess calcium ions relative to the seawater concentration.

Effect of (a) low salinity brine, (b, c, d) symbiotic behavior of PDIs, and (e) individual PDI, Ca2+, \(\:{\text{S}\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\), Mg2+ on static contact angle alteration of oil-wet thin section, illustrated on the third day for S-1 formation.

In addition, SW0 Ca0S and SW0 Ca0Mg perform best in reducing the angle of contact, respectively, which indicates the effective role of sulfate and magnesium ions in changing wettability individually. According to Supplementary Figure S-8, Considering the results of contact angle measurements for the S-1 formation, the best injection waters are SW2S, SW4 Ca, and SW0 Ca0S.

The contact angle reduction with SW2S demonstrates a transition from an oil-wet to a more water-wet carbonate surface. This change is likely driven by sulfate ions adsorbing onto the positively charged carbonate rock (calcite), which typically attracts negatively charged oil components like carboxylic acids. By adsorbing, sulfate ions weaken these electrostatic interactions, displacing oil molecules and allowing water to spread more readily across the surface. Figure 17 shows that this mechanism is particularly effective in systems with high resin and asphaltene content (S-1 and F-2), as these polar components enhance oil-rock adhesion, making sulfate-mediated displacement more impactful.

Table 5 summarizes the IFT and ∆CA (Eq. 2) results obtained for five formations, which can be used to select the best SmW. SW2S caused the most IFT reduction in almost all formations. Besides, SW2S alters the rock’s wettability more than other solutions. As a result, SW2S was chosen for core flooding tests.

∆CA = CAoil/FW - CAoil/SmW (2).

Core flooding results

This section will discuss the core flooding results for S-1, K-1, and F-1 formations. Figures 18 and 19, and Fig. 20 show the oil recovery after different injection scenarios. As mentioned above, to ascertain the effects of SmW on oil recovery, FW, SW, and SW2S were injected, respectively, and the oil recovery was measured at 10 PV for each water injection.

Figure 18 plots oil recovery and pressure drop versus PV for FW, SW, and SW2S injection water in the S-1 formation. As shown in Fig. 18, FW injection at the first injection scenario caused 68.45% oil recovery. Then, the oil recovery will be enhanced by 5.51% after SW flooding. Finally, The enhanced oil recovery observed with SW2S, which increased recovery by 10.27% in the S-1 formation compared to seawater, can be attributed to its dual impact on wettability alteration and IFT reduction. In carbonate reservoirs, the rock surface is typically positively charged due to calcium and magnesium ions, promoting the adsorption of negatively charged carboxylic acids from the oil, rendering the surface oil wet. SW2S, with its elevated sulfate concentration, introduces negatively charged sulfate ions that adsorb onto the rock surface. This adsorption competes with and displaces the oil components, establishing a water film between the rock and oil, thus shifting the wettability toward a more water-wet state. This mechanism aligns with findings by Zhang et al. (2006)4, who demonstrated sulfate’s role in altering carbonate wettability. Simultaneously, SW2S significantly reduced IFT, particularly for crude oils rich in resins and asphaltenes, such as S-1. This reduction likely results from sulfate ions interacting with the polar groups of these components at the oil-water interface. By coordinating with these molecules, sulfate ions may alter their orientation or form complexes, lowering the interfacial energy and, thus, the IFT.

Additionally, SW2S promotes the formation of stable emulsions in the S-1 crude oil system, where the high resin and asphaltene content serve as natural emulsifiers. These emulsions form as sulfate ions enhance oil dispersion into the water phase, stabilized by the polar oil components adsorbing at the droplet interfaces. This process increases the viscosity of the displacing fluid, improving sweep efficiency by reducing the mobility ratio and ensuring a more uniform displacement front across the reservoir. Furthermore, the emulsions mobilize trapped oil droplets, carrying them within the water phase and enhancing recovery from the oil-wet pores of the S-1 crude oil porous media. This emulsion mechanism, synergistic with IFT reduction and wettability alteration, significantly contributes to the 10.27% recovery increase, an effect amplified by the polar-rich nature of S-1 crude oil. This effect is more pronounced in oils with higher polar content, explaining the variability across formations. Austad et al. (2010) similarly noted that ionic interactions with oil components can enhance IFT reduction in low-salinity flooding10.

According to Fig. 19, the first injection scenario of FW injection caused an oil recovery of 84.03% for the K-1 formation. The incremental oil recovery will be 3.42% after SW flooding. Finally, SW2S injection improved oil recovery by 6.55%.

According to Fig. 20, FW injection in the first scenario caused 76.64% oil recovery for the F-1 formation. The incremental oil recovery will be 7.44% after SW flooding. Finally, SW2S injection improved oil recovery by 5.51%.

These combined effects, wettability alteration and IFT reduction, facilitate oil displacement. In the S-1 formation, the substantial reductions in both IFT and contact angle with SW2S correlate directly with the observed recovery improvement. In contrast, formations like K-1 and F-1, with less pronounced changes, exhibited smaller recovery gains, underscoring the role of oil composition in modulating these mechanisms.

Conclusion

Through a series of experimental tests, the ionic effect of engineered water on the contact angle, interfacial tension, and improving oil recovery was fully explored in this work. Based on the experimental and simulation results, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

The highest amount of total minerals formed is related to mixing formation water with SW4S.

-

Crude oil components significantly affect the effectiveness of PDIs. Depending on the oil type, each PDI could have various effects.

-

The importance of sulfate ions in driving wettability alteration and IFT reduction offers insights for optimizing engineered water in carbonate reservoirs.

-

LSW does not positively affect IFT reduction in crude oils containing resin particles.

-

The oil containing resin and asphaltene has a higher IFT reduction than other samples.

-

The injection brine with only Ca (SW0S0Mg) significantly reduces IFT for oils containing the minimum amount of asphaltene.

-

The existence of resin particles in crude oil influences the effectiveness of different PDIs.

-

In almost all formations, SW2S caused the most IFT reduction and wettability alteration compared to other solutions.

-

The core flooding results show that SW2S injection has the most oil recovery at the S-1 formation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

5. References

Hezave, A. Z., Dorostkar, S., Ayatollahi, S., Nabipour, M. & Hemmateenejad, B. Investigating the effect of ionic liquid (1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([C12mim] [Cl])) on the water/oil interfacial tension as a novel surfactant. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 421, 63–71 (2013).

Austad, T. Water-Based EOR in carbonates and sandstones: new chemical Understanding of the EOR potential using smart water. Enhanced Oil Recovery Field Case Stud. 301–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386545-8.00013-0 (2013).

Kandala, V. & Govindarajan, S. K. Numerical investigations of Low-Salinity water flooding in a saline sandstone reservoir. J. Energy Eng. 149, (2023).

Zhang, P. & Austad, T. Wettability and oil recovery from carbonates: effects of temperature and potential determining ions. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 279, 179–187 (2006).

Yousef, A. A., Al-Saleh, S., Al-Kaabi, A. & Al-Jawfi, M. Laboratory investigation of the impact of Injection-Water salinity and ionic content on oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 14, 578–593 (2011).

Lashkarbolooki, M., Ayatollahi, S. & Riazi, M. Effect of salinity, resin, and asphaltene on the surface properties of acidic crude oil/smart water/rock system. Energy Fuels. 28, 6820–6829 (2014).

Honarvar, B., Rahimi, A., Safari, M., Khajehahmadi, S. & Karimi, M. Smart water effects on a crude oil-brine-carbonate rock (CBR) system: further suggestions on mechanisms and conditions. J. Mol. Liq. 299, 112173 (2020).

Sheng, J. J. Critical review of low-salinity waterflooding. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 120, 216–224 (2014).

Ali Buriro, M., Wei, M., Bai, B. & Yao, Y. Advances in smart water flooding: A comprehensive study on the interplay of ions, salinity in carbonate reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 123140 (2023).

Austad, T., RezaeiDoust, A. & Puntervold, T. Chemical mechanism of low salinity water flooding in sandstone reservoirs. Proc. - SPE Symp. Improved Oil Recovery. 1, 679–695 (2010).

Qiao, W., Li, J., Zhu, Y. & Cai, H. Interfacial tension behavior of double long-chain 1,3,5-triazine surfactants for enhanced oil recovery. Fuel 96, 220–225 (2012).

Srivastava, V. R., Mitra, S., Gopal, G. & Gupta, S. K. Interpreting Screening of Appropriate Carbonate Reservoir for Low Salinity Water Flood EOR in Giant Indian Offshore Fields. Offshore Technology Conference Asia, OTCA 2024 (2024). https://doi.org/10.4043/34751-MS

Fathi, S. J., Austad, T. & Strand, S. Effect of Water-Extractable carboxylic acids in crude oil on wettability in carbonates. Energy Fuels. 25, 2587–2592 (2011).

Jadhunandan, P. P. & Morrow, N. R. Effect of wettability on waterflood recovery for Crude-Oil/Brine/Rock systems. SPE. Reserv. Eng. 10, 40–46 (1995).

Quintella, C. M. et al. Smart Water as a Sustainable Enhanced Oil Recovery Fluid: Covariant Saline Optimization. Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, OTCB 2023 (2023). https://doi.org/10.4043/32800-MS

Rezaeidoust, A., Puntervold, T., Strand, S. & Austad, T. Smart water as wettability modifier in carbonate and sandstone: A discussion of similarities/differences in the chemical mechanisms. Energy Fuels. 23, 4479–4485 (2009).

Massarweh, O. & Abushaikha, A. S. The synergistic effects of cationic surfactant and smart seawater on the recovery of medium-viscosity crude oil from low-permeability carbonates. J. Mol. Liq. 389, 122866 (2023).

Shahrabadi, A., Babakhani Dehkordi, P., Razavirad, F., Noorimotlagh, R. & Nasiri Zarandi, M. Enhanced oil recovery from a carbonate reservoir during low salinity water flooding: spontaneous imbibition and Core-Flood methods. Nat. Resour. Res. 31, 2995–3015 (2022).

Batias, J., Hamon, G., Lalanne, B. & Romero, C. FIELD AND LABORATORY OBSERVATIONS OF REMAINING OIL SATURATIONS IN A LIGHT OIL RESERVOIR FLOODED BY A LOW SALINITY AQUIFER. (2009).

Kaliyugarasan, J. Surface Chemistry Study of Low Salinity Waterflood. (2013).

Moeini, F., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Ghazanfari, M. H., Masihi, M. & Ayatollahi, S. Toward mechanistic Understanding of heavy crude oil/brine interfacial tension: the roles of salinity, temperature and pressure. Fluid Phase Equilib. 375, 191–200 (2014).

Morrow, N. & Buckley, J. Improved oil recovery by Low-Salinity waterflooding. J. Petrol. Technol. 63, (2011).

Tang, G. Q. & Morrow, N. R. Influence of Brine composition and fines migration on crude oil/brine/rock interactions and oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 24, 99–111 (1999).

Li, L. et al. Zwitterionic-nonionic compound surfactant system with low chromatographic separation effect for enhanced oil recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 123004 (2023).

Yousef, A. A., Al-Saleh, S. & Al-Jawfi, M. New recovery method for carbonate reservoirs through tuning the injection water salinity: smart waterFlooding. 73rd Eur. Association Geoscientists Eng. Conf. Exhib. 2011: Unconv. Resour. Role Technol. Incorporating SPE EUROPEC 2011. 4, 2814–2830 (2011).

Al-Attar, H. H., Mahmoud, M. Y., Zekri, A. Y., Almehaideb, R. A. & Ghannam, M. T. Low Salinity Flooding in a Selected Carbonate Reservoir: Experimental Approach. (2013). https://doi.org/10.2118/164788-MS

Ayirala, S. C., Al Yousef, A. A., Li, Z. & Xu, Z. Water ion interactions at crude Oil-Water interface: A new fundamental Understanding on SmartWater flood. SPE Middle East. Oil Gas Show. Conf. MEOS Proc. 2017-March, 2948–2964 (2017).

Varadaraj, R. & Brons, C. Molecular origins of crude oil interfacial activity. Part 4: oil–Water interface elasticity and crude oil asphaltene films. Energy Fuels. 26, 7164–7169 (2012).

Criddle, D. W. & Meader, A. L. Viscosity and elasticity of oil surfaces and oil-Water interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 26, 838–842 (1955).

Hasiba, H. & Jessen, F. Film Properties Of Interface-Active Compounds Adsorbed From Crude Oils At The Oil/Water Interface. in 18th annual technical meeting, the petroleum society of CIM (1967).

Buckley, J. S., Takamura, K. & Morrow, N. R. Influence of electrical surface charges on the wetting properties of crude oils. SPE. Reserv. Eng. 4, 332–340 (1989).

Chen, J., Hirasaki, G. J. & Flaum, M. NMR wettability indices: effect of OBM on wettability and NMR responses. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 52, 161–171 (2006).

Mohammed, M. & Babadagli, T. Wettability alteration: A comprehensive review of materials/methods and testing the selected ones on heavy-oil containing oil-wet systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 220, 54–77 (2015).

Saikia, B. D., Mahadevan, J. & Rao, D. N. Exploring mechanisms for wettability alteration in low-salinity waterfloods in carbonate rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 164, 595–602 (2018).

Ding, H. & Rahman, S. Experimental and theoretical study of wettability alteration during low salinity water flooding-an state of the Art review. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 520, 622–639 (2017).

AlQuraishi, A. A., AlHussinan, S. N. & AlYami, H. Q. Efficiency and Recovery Mechanisms of Low Salinity Water Flooding in Sandstone and Carbonate Reservoirs. Preprint at https://dx.doi.org/ (2015).

Kakati, A. & Sangwai, J. S. Effect of monovalent and divalent salts on the interfacial tension of pure hydrocarbon-brine systems relevant for low salinity water flooding. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 157, 1106–1114 (2017).

Deng, X. et al. Relative contribution of wettability alteration and interfacial tension reduction in EOR: A critical review. J. Mol. Liq. 325, 115175 (2021).

Lashkarbolooki, M. & Ayatollahi, S. Experimental and modeling investigation of dynamic interfacial tension of asphaltenic–acidic crude oil/aqueous phase containing different ions. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 25, 1820–1830 (2017).

Mohammadkhani, S., Shahverdi, H., Kling, K. I., Feilberg, K. L. & Esfahany, M. N. Characterization of interfacial interactions and emulsification properties of bicarbonate solutions and crude oil and the effects of temperature and pressure. J. Mol. Liq. 305, 112729 (2020).

Bashforth, F. & Adams, J. C. An attempt to test the theories of capillary action by comparing the theoretical and measured forms of drops of fluid. With an explanation of the method of integration employed in constucting the tables which give the theoretical forms of such drops. (Cambridge [Eng.] University Press, 1883).

Xing, W. et al. Research progress of the interfacial tension in supercritical CO2-water/oil system. Energy Procedia. 37, 6928–6935 (2013).

Kumar, B. Effect of salinity on the interfacial tension of model and crude oil systems. (2012). (2012).

Ardakani, S. F. G., Hosseini, S. T. & Kazemzadeh, Y. A review of scale inhibitor methods during modified smart water injection. Can. J. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1002/CJCE.25293 (2024).

Nasralla, R. A. et al. Low salinity waterflooding for a carbonate reservoir: experimental evaluation and numerical interpretation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 164, 640–654 (2018).

Yousef, A. A. et al. SmartWater flooding: Industry’s first field test in carbonate reservoirs. Proceedings - SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition 3, 2469–2494 (2012).

Ayirala, S. C. & Yousef, A. A. Injection water chemistry requirement guidelines for IOR/EOR. Proc. - SPE Symp. Improved Oil Recovery. 1, 242–265 (2014).

Xie, Q., Saeedi, A., Pooryousefy, E. & Liu, Y. Extended DLVO-based estimates of surface force in low salinity water flooding. J. Mol. Liq. 221, 658–665 (2016).

Madadizadeh, A., Sadeghein, A. & Riahi, S. The use of nanotechnology to prevent and mitigate fine migration: A comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 38, 1–16 (2022).

Sadeghein, A., Abbaslu, A., Riahi, S. & Hajipour, M. Comprehensive analysis of fine particle migration and swelling: impacts of salinity, pH, and temperature. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 240, 213044 (2024).

Baraka-Lokmane, S. & Sorbie, K. S. Effect of pH and scale inhibitor concentration on phosphonate–carbonate interaction. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 70, 10–27 (2010).

Azizi, J., Shadizadeh, S. R., Khaksar Manshad, A. & Mohammadi, A. H. A dynamic method for experimental assessment of scale inhibitor efficiency in oil recovery process by water flooding. Petroleum 5, 303–314 (2019).

Graham, G. M., Boak, L. S. & Sorbie, K. S. The influence of formation calcium and magnesium on the effectiveness of generically different barium sulphate oilfield scale inhibitors. SPE Prod. Facil. 18, 28–44 (2003).

Okasha, T. M., Nasr-El-Din, H. A., Saiari, H. A., Al-shiwaish, A. A. & Al-Zubaidi, F. F. Trondheim, Norway,. Impact of a Novel Scale Inhibitor System on the Wettability of Paleozoic Unayzah Sandstone Reservoir, Saudi Arabia. in Oral presentation given at the International Symposium of the Society of Core Analysts (2006).

Zhang, L., Kim, D. & Jun, Y. S. The effects of Phosphonate-Based scale inhibitor on Brine-Biotite interactions under subsurface conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 6042–6049 (2018).

Dordzie, G. & Dejam, M. Enhanced oil recovery from fractured carbonate reservoirs using nanoparticles with low salinity water and surfactant: A review on experimental and simulation studies. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 293, 102449 (2021).

Collins, A. G. Enhanced-Oil-Recovery injection waters. All Days. https://doi.org/10.2118/6603-MS (1977).

Al Kalbani, M. M., Jordan, M. M., Mackay, E. J., Sorbie, K. S. & Nghiem, L. Barium sulfate scaling and control during polymer, surfactant, and surfactant/polymer flooding. SPE Prod. Oper. 35, 068–084 (2020).

Puntervold, T., Strand, S. & Austad, T. Water flooding of carbonate reservoirs: effects of a model base and natural crude oil bases on chalk wettability. Energy Fuels. 21, 1606–1616 (2007).

Moghadasi, J., Jamialahmadi, M., Müller-Steinhagen, H. & Sharif, A. Scale formation in oil reservoir and production equipment during water injection kinetics of CaSO4 and CaCO3 crystal growth and effect on formation damage. (2003). https://doi.org/10.2118/82233-MS

Stalker, R., Collins, I. R. & Graham, G. M. The impact of chemical incompatibilities in commingled fluids on the efficiency of a produced water reinjection system: A North sea example. SPE Int. Symp. Oilfield Chem. 441-453 https://doi.org/10.2118/80257-MS (2003).

Liu, X. et al. Understanding the Co-deposition of calcium sulphate and barium sulphate and developing environmental acceptable scale inhibitors applied in HTHP wells. Soc. Petroleum Eng. - SPE Int. Conf. Exhib. Oilfield Scale. 2012, 607–616. https://doi.org/10.2118/156013-MS (2012).

Jarrahian, K., Sorbie, K., Singleton, M., Boak, L. & Graham, A. Building a Fundamental Understanding of Scale Inhibitor Retention in Carbonate Formations. Proceedings - SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry (2019). (2019).

Mohammadi, M. & Riahi, S. Experimental investigation of water incompatibility and rock/fluid and fluid/fluid interactions in the absence and presence of scale inhibitors. SPE J. 25, 2615–2631 (2020).

Yeh, S. L., Koshani, R. & Sheikhi, A. Colloidal aspects of calcium carbonate scaling in water-in-oil emulsions: A fundamental study using droplet-based microfluidics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 633, 536–545 (2023).

Kang, D., Yoo, Y. & Park, J. Accelerated chemical conversion of metal cations dissolved in seawater-based reject Brine solution for desalination and CO2 utilization. Desalination 473, 114147 (2020).

Diallo, M. S., Kotte, M. R. & Cho, M. Mining critical metals and elements from seawater: opportunities and challenges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 9390–9399 (2015).

Kumar, A. et al. Metals recovery from seawater desalination Brines: technologies, opportunities, and challenges. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 7704–7712 (2021).

Ihsanullah, I. et al. Waste to wealth: A critical analysis of resource recovery from desalination Brine. Desalination 543, 116093 (2022).

Chatla, A. et al. Sulphate removal from aqueous solutions: State-of-the-art technologies and future research trends. Desalination 558, 116615 (2023).

Marshall, W. L. & Slusher, R. Thermodynamics of calcium sulfate dihydrate in aqueous sodium chloride solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 70, 4015–4027 (1966).

Misono, T. Interfacial tension between water and oil. Meas. Techniques Practices Colloid Interface Phenom. 39-44 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5931-6_6 (2019).

Lashkarbolooki, M. & Ayatollahi, S. Thermophysical interface properties of crude oil and aqueous solution containing sulfate anions: experimental and modeling approaches. Pet. Sci. Technol. 37, 2167–2173 (2019).

Abdi, A., Awarke, M., Malayeri, M. R. & Riazi, M. Interfacial tension of smart water and various crude oils. Fuel 356, 129563 (2024).

Hamidian, R., Lashkarbolooki, M. & Amani, H. Evaluation of surface activity of asphaltene and resin fractions of crude oil in the presence of different electrolytes through dynamic interfacial tension measurement. J. Mol. Liq. 300, 112297 (2020).

Chávez-Miyauch, T. E., Lu, Y. & Firoozabadi, A. Low salinity water injection in Berea sandstone: effect of wettability, interface elasticity, and acid and base functionalities. Fuel 263, 116572 (2020).

Lashkarbolooki, M., Riazi, M., Ayatollahi, S. & Zeinolabedini Hezave, A. Synergy effects of ions, resin, and asphaltene on interfacial tension of acidic crude oil and low–high salinity Brines. Fuel 165, 75–85 (2016).

Lashkarbolooki, M. & Ayatollahi, S. Effect of asphaltene and resin on interfacial tension of acidic crude oil/ sulfate aqueous solution: experimental study. Fluid Phase Equilib. 414, 149–155 (2016).

John, C., Kotz, P. M. & Treichel John Townsend & David Treichel. Chemistry & Chemical ReactivityCengage Learning,. (2014).

Behrang, M., Hosseini, S. & Akhlaghi, N. Effect of pH on interfacial tension reduction of oil (Heavy acidic crude oil, resinous and asphaltenic synthetic oil)/low salinity solution prepared by chloride-based salts. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 205, 108840 (2021).

Lashkarbolooki, M., Riazi, M., Hajibagheri, F. & Ayatollahi, S. Low salinity injection into asphaltenic-carbonate oil reservoir, mechanistical study. J. Mol. Liq. 216, 377–386 (2016).

Mokhtari, R. & Ayatollahi, S. Dissociation of Polar oil components in low salinity water and its impact on crude oil–brine interfacial interactions and physical properties. Pet. Sci. 16, 328–343 (2019).

Ahmadi Aghdam, M., Riahi, S. & Khani, O. Experimental study of the effect of oil polarity on smart waterflooding in carbonate reservoirs. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1 14, 1–18 (2024).

Kwok, D. Y. & Neumann, A. W. Contact angle measurement and contact angle interpretation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 81, 167–249 (1999).

Mittal, K. L. Advances in Contact Angle, Wettability and Adhesion. Advances in Contact Angle, Wettablility and Adhesionvol. 3 (Wiley, 2018).

Boumedjane, M., Karimi, M., Al-Maamari, R. S. & Aoudia, M. Experimental investigation of the concomitant effect of potential determining ions Mg2+/SO42 – and Ca2+/SO42 – on the wettability alteration of oil-wet calcite surfaces. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 179, 574–585 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. : Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, ConceptualizationM.A.A : Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, ConceptualizationA.S. : Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, ConceptualizationS.H. : Software, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, ConceptualizationS.R. : Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administrationS.S : Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Madadizadeh, A., Aghdam, M.A., Sadeghein, A. et al. Ionic optimization of engineered water for enhanced oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs: A case study. Sci Rep 15, 15665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99203-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99203-5