Abstract

Adolescent antisocial behavior not only has an adverse effect on the healthy development of adolescents but also poses a threat to social order and public safety. The study included 18,470 high school students during the 2020–2023 school year as study participants. Random forest was used to assess the importance of influencing factors, and binary logistic regression analysis was conducted on the top eight identified factors. The study included 18,470 participants, consisting of 8867 boys and 9603 girls. The results showed that parents’ educational expectations (boys: OR = 0.942, girls: OR = 0.903) and smoking behavior (boys: OR = 1.055, girls: OR = 1.066) were common factors affecting antisocial behavior in both boy and girl adolescents. The number of good friends (OR = 1.122), current place of residence (OR = 1.039), and engage in regular physical activity (OR = 0.916) were specific influencing factors for boy adolescents’ antisocial behavior, while family economic conditions (OR = 1.092) was specific influencing factor for girl adolescents’ antisocial behavior. The study showcases Random Forest Model and the Logistic Model can effectively identify and analyze influencing factors, and the model performance is good. The identified influencing factors and their effects show gender differences. Therefore, we should formulate targeted prevention and improvement measures for adolescents’ anti-social behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social behavior is defined as the recurrent violation of socially accepted norms, encompassing actions such as aggression, defiance, and lack of self-regulation1. Adolescence, a critical developmental stage, is marked by physical growth, academic engagement, and the development of social interaction skills. Furthermore, during this period, adolescents face various stressors, particularly those related to academic performance and social relationships, which can lead to the accumulation of negative emotions2, manifested in impulsivity and irritability. As adolescents mature, their desire for autonomy and independence intensifies, often exacerbating psychological resistance and defiant behaviors3. Consequently, due to their unique physiological and psychological development and exposure to multiple stressors, adolescents are more likely to exhibit antisocial tendencies compared to other age groups. These tendencies not only hinder their mental and physical well-being but also pose significant challenges to societal harmony and stability.

The General Aggression Model4 posits that human aggression is influenced by a broad range of input variables. These variables affect cognition, emotion, and arousal, which, in conjunction with other factors, determine whether aggression occurs and in what form. Accordingly, the factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior are multifaceted. From an individual perspective, mental health issues5,6 contribute to aggression through two distinct pathways: emotional arousal and hostile attribution bias. Additionally, problem behavior theory suggests that certain lifestyle behaviors—including smoking7, alcohol consumption8, screen time9, and sleep quality10—are closely linked to adolescents’ emotional regulation, value systems, and moral judgment, thus influencing their propensity for antisocial behavior. From a family perspective, disproportionate parental educational expectations11—whether excessively high, leading to academic pressure, or too low, resulting in a lack of rule awareness—can exacerbate antisocial tendencies. Furthermore, geographic remoteness12 and socioeconomic disadvantages13,14 can limit access to educational resources and opportunities, further intensifying antisocial behavior among adolescents. From a social perspective, individuals with heightened interpersonal sensitivity15 are more likely to adopt hostile or avoidant responses in social interactions. According to social bond theory, strong social connections foster adherence to social norms and reduce the likelihood of deviant behavior. Consequently, factors such as the number of friendships16 and satisfaction with interpersonal relationships17 play a crucial role in shaping an individual’s emotional state and behavioral patterns.

According to affective attribution theory, in social interactions, males are more likely to attribute negative emotions to external factors, thereby releasing emotions, whereas females tend to attribute them to internal factors, leading to a greater tendency to self-isolate18. This results in boys being more susceptible to antisocial behaviors19. Therefore, it is necessary to move beyond the idea of simply comparing the differences in male–female antisocial behaviors, and to explore in-depth from the gender differences to the factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior in terms of universal and specific factors.

Although existing literature has identified numerous factors influencing antisocial behavior, several limitations persist: (1) There is limited research specifically focusing on adolescent populations. (2) Gender-based comparative studies have largely relied on statistical differences, without delving into gender-specific mechanisms. (3) Most studies utilize single-factor analyses, regression models, or correlation analyses, typically investigating influencing factors in isolation. This approach fails to compare the relative importance of multiple variables, leaving critical driving factors concealed within a broad set of predictors.

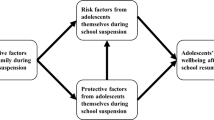

To address these gaps, this study focuses on adolescents as the target population and employs random forest modeling, stratified by gender. This approach generates a large number of decision trees based on bootstrapped data, with each node’s splitting variable selected from a randomly chosen subset of predictor variables. The final prediction is determined by a majority vote among all trees. This method allows for the assessment of the relative importance of influencing factors, offering valuable reference points for subsequent statistical regression analyses and enhancing statistical power20. Furthermore, we incorporate logistic regression analysis to quantify and directly interpret the impact and direction of each variable within the model, thereby addressing the interpretability limitations of random forests. The primary objective of this study is to accurately identify key factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior and to explore the core driving mechanisms underlying gender differences. These findings will offer valuable insights for the development of targeted interventions aimed at effectively reducing adolescent antisocial behavior.

Methods

Study participants

This study used stratified and random sampling methods to conduct a cross-sectional survey. Thirty high schools (15 rural high schools and 15 urban high schools) were randomly selected from 16 prefecture-level cities in Shandong Province, China (Jinan, Qingdao, Zibo, Zaozhuang, Dongying, Yantai, Weifang, Jining, Tai’an, Weihai, Rizhao, Linyi, Dezhou, Liaocheng, Binzhou, Heze), representing both urban districts and rural administrative villages. A total of 18,600 high school students from the 2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023 academic years participated in the survey, which was conducted in December 2020, December 2021, and December 2022, respectively. The questionnaire was administered through the online platform MIKECRM, with students completing the survey under the supervision of professional investigators to ensure accuracy and reliability. A total of 18,470 valid questionnaires were gathered, with a response rate of 99.3%. The data from the questionnaire survey were included in the Population Health Data Archive (PHDA) adolescent health theme database21.This database primarily focuses on conducting longitudinal research into adolescent health, leveraging on-site testing, questionnaires, data collection, and other methodologies to acquire health resource data pertaining to adolescents. The data it provides serve as a vital resource for research in various domains such as physical fitness, mental and psychological wellbeing, nutrition and dietary habits, quality of life, social health, risky behaviors, and physical activity patterns among adolescents (junior and senior high school students). Furthermore, it offers a solid data foundation for informing decision-making processes within educational administration and government bodies.

Measures

General information questionnaire

The socio-demographic information includes gender, current place of residence, whether or not you are an only child, your family’s economic condition, and whether or not you live at the school. In addition, we included relevant surveys about participants’ health behaviors, mental status, and social relationships, smoking behavior, drinking behavior, engage in regular physical activity, and daily screen time, how much your friends care about you, worried about doing the wrong thing, take the initiative to talk to your parents, easy to feel nervous or scared, frequent fellings of tiredness or lack of energy, parents’ education expectations of your, satisfaction with relationship with parents, number of good friends, satisfaction with relationship, availability of computers and internet.

School social behavior scale-2(SSBS-2)

The School Social Behavior Scale-2 (SSBS-2), developed by Merrell22, was employed in this study. The scale consists of two subscales: “Social Skills” and “Antisocial Behavior,” with responses rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Frequently). The antisocial behavior subscale, used in this study, comprises 33 items. An average score below 1.5 indicates the absence of antisocial behavior, while an average score of 1.5 or above suggests the presence of antisocial behavior. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this subscale was 0.962, indicating high internal consistency and reliability.

Symptom checklist 90 (SCL-90)

The “Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90)” developed by Derogatis was used23. The scale was used for the measurement of mental health and behavioral problems. The items were rated on a scale from 1 (none) to 5 (severe) and consisted of 90 items in nine subscales: somatization (1, 4, 12, 27, 40, 42, 48, 49, 52, 53, 56, 58), anxiety (2, 17, 23, 33, 39, 57, 72, 78, 80, 86), depression (5, 14, 15, 20, 22, 26 , 29, 30, 31, 32, 54, 71, 79), interpersonal sensitivity (6, 21, 34, 36, 37, 41, 61, 69, 73), hostility (11, 24, 63, 67, 74, 81), obsessive–compulsive (3, 9, 10, 28, 38, 45, 46, 51, 55, 65), phobic-anxiety (13, 25, 47, 50, 70, 75, 82), paranoid ideation (8, 18, 43, 68, 76, 83) and psychoticism (7, 16, 35, 62, 77, 84, 85, 87, 88, 90). Mean subscale scores indicate: 1 = none, 1 < mild < 2, 2 < moderate < 3, 3 < severe < 4, 4 < very severe ≤ 5. The higher the score, the more severe the symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.987.

Variable design

Dependent variable

In this study, antisocial behavior is used as the dependent variable in the model construction. Since antisocial behavior cannot be directly observed or measured, this paper uses the antisocial dimension questions from the School Social Behavior Scale-2 (SSBS-2) for measurement. 0 indicates no antisocial behavior, and 1 indicates the presence of antisocial behavior.

Independent variables

The specific assignments for each variable are shown in Table 1. Based on previous research on antisocial behavior, the study selected 28 variables, such as current place of residence and whether the participant is an only child, as explanatory variables.

Statistical analysis

This study used SPSS 27.0 software for descriptive statistics and t-tests. Python (version 3.9) was used to write the random forest model to assess the importance of factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior, and the GridSearchCV method was employed to find the optimal parameters for the model. The important variables selected by the random forest model were placed into the binary logistic regression model for adolescent antisocial behavior, and the OR values were used to quantitatively explain the important factors, further elaborating on the specific magnitude of changes in adolescent antisocial behavior with the important factors. This approach of combining random forest with logistic regression is beneficial for improving the effectiveness of testing.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The survey questionnaire was submitted to the Ethics Committee of Shandong University in February 2018 and received ethical approval in May 2018 (Approval No. 20180517).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Differences in scores for each influencing factor between genders are shown in Table 2. The results show that there were 8867 boys (age:16.42 ± 1.00) and 9603 girls (age:16.43 ± 0.99). Boys scored significantly higher than girls in terms of the number of good friends, smoking behavior, daily screen time, drinking behavior, engage in regular physical activity, and satisfaction with sleep quality. girls scored higher than boys in somatization, whether they are an only child, phobic anxiety, psychoticism, obsession-compulsive, paranoid ideation, frequent feeling of tiredness or lack of energy, take the initiative to talk to parents, hostility, anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, worried about doing the wrong thing, how much your friends care about you, availability of computers and internet, easy to feel nervous or scared, whether or not you live at the school, satisfaction with relationship with parents, and parents’ educational expectations. There were no significant differences in family economic conditions and satisfaction with relationship with teachers.

Importance of factors influencing antisocial behavior

Traditional analytical methods often can only simply describe the direction and degree of the effect of explanatory variables on the explained variable, but they cannot rank the importance of various factors. In this study, the survey population was divided into two groups by gender, boy and girl, with antisocial behavior as the dependent variable. A random forest model was constructed to assess the importance of 28 factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior, and to explore the factors that influence antisocial behavior in boy and girl adolescents separately. The model accuracy (boy: 0.775, girl: 0.781) was good.

The percentage of importance of each influencing factor is shown in Figs. 1 and 2. According to the evaluation results of the random forest model, the study found that how much your friends care about you, smoking behavior, parents’ educational expectations, the number of good friends, daily screen time, current place of residence, family economic conditions, and engage in regular physical activity are the eight relatively important factors influencing antisocial behavior in boy adolescents, while parents’ educational expectations, daily screen time, how much your friends care about you, smoking behavior, family economic conditions, current place of residence, engage in regular physical activity, and satisfaction with sleep quality are the eight relatively important factors influencing antisocial behavior in girl adolescents.

Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing antisocial behavior

This study used antisocial behavior as the dependent variable and placed the eight relatively important factors identified by the random forest model into a binary logistic regression model to explore the impact of these factors on adolescent antisocial behavior. The model accuracy (boy: 0.772, girl: 0.773) was considered good.

The results of the logistic regression for the different influencing factors are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Among the factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior, parents’ educational expectations (boy: OR = 0.942, girl: OR = 0.903) and smoking behavior (boy: OR = 1.055, girl: OR = 1.066) were common factors affecting antisocial behavior in both boy and girl adolescents. Higher educational expectations from parents can reduce the occurrence of antisocial behavior in both boy and girl adolescents, while frequent smoking behavior can increase the occurrence of antisocial behavior in both genders. The number of good friends (OR = 1.122), current place of residence (OR = 1.039), and engage in regular physical activity (OR = 0.916) were specific factors influencing antisocial behavior in boy adolescents. A higher number of friends and living in towns and rural areas can increase the occurrence of antisocial behavior in boy adolescents, while an increase in physical exercise can effectively reduce the occurrence of antisocial behavior in boy adolescents. Family economic conditions (OR = 1.092) was specific factor influencing antisocial behavior in girl adolescents. Better family economic conditions can increase the occurrence of antisocial behavior in girl adolescents.

Discussion

This study employed random forest modeling and logistic regression analysis to examine the factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior and the associated gender differences. The random forest model ranked the importance of these factors, and the top eight were subsequently included in the logistic regression model for further analysis. Two key findings emerged. First, among the various influencing factors, parents’ educational expectations, smoking behavior, number of good friends, current place of residence, engage in regular physical activity, and family economic condition were identified as the primary determinants of adolescent antisocial behavior. Second, significant gender differences were observed in the impact of these factors. Specifically, parents’ educational expectations and smoking behavior were universal risk factors influencing antisocial behavior in both boy and girl adolescents. The number of good friends, current place of residence, and engage in regular physical activity were found to be boy-specific factors, while family economic condition was girl-specific factor. To the best of our knowledge, this study offers novel insights into the influencing factors of adolescent antisocial behavior.

The findings indicate that higher parents’ educational expectations exert a significant inhibitory effect on adolescent antisocial behavior, consistent with previous research. In the context of ongoing educational urbanization and the growing societal emphasis on upward mobility, parental expectations for their children’s education continue to rise24. Existing studies suggest that parental educational expectations not only enhance adolescents’ academic self-efficacy but also promote sustained attentional focus, helping them establish clear developmental goals. This goal-directed mechanism encourages adolescents to maintain structured learning plans and exercise self-discipline in behavioral management25, thereby reducing deviant behaviors through goal commitment. From a family interaction perspective, high educational expectations often signal greater parental investment in education. Such parenting practices can strengthen emotional bonds between parents and children, buffering the negative effects of social environmental stressors on adolescent mental health26, which in turn decreases the likelihood of emotion-driven behavioral dysregulation.

Adolescence is a critical period for brain development, during which the nervous system remains relatively unstable and is particularly vulnerable to external influences, such as nicotine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors27. Nicotine activates the dopamine system, reinforcing the rewarding effects of smoking. These neuroadaptive changes impair impulse control, thereby increasing the likelihood of aggression, rule-breaking, and other antisocial behaviors. Furthermore, adolescents who smoke are more prone to adopting externalizing coping strategies in response to stress, which has been linked to heightened hostility28 and an increased risk of schizophrenia8. Additionally, smoking has been associated with suicidal tendencies29. Together, these findings suggest that smoking behavior exacerbates the risk of adolescent antisocial behavior.

Previous research has demonstrated that when adolescents face setbacks, they typically seek support from friends, gaining diverse emotional support and advice. A larger social network provides varied emotional outlets, helping to prevent the buildup of negative emotions30, thereby reducing mental health issues and maladaptive behaviors. This, in turn, reduces the likelihood of adolescent antisocial behavior. However, contrary to previous studies, this research found that an excessive number of friends may increase the risk of antisocial behavior. This is attributed to a threshold effect31, where the impact of friendships varies across individuals. As adolescents are particularly vulnerable to external influences, an increase in the number of friends heightens their exposure to risky behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption32. Additionally, adolescents with a larger social circle are more likely to form cliques, which can foster school bullying behaviors33, thus increasing the likelihood of antisocial conduct. Further analysis revealed gender-specific differences: girls prioritize the emotional quality of close relationships and tend to be more selective in choosing friends34. Consequently, they maintain smaller, more stable social circles, which helps protect them from the negative influences of larger peer groups. In contrast, boys seek social recognition and self-identity fulfillment during adolescence, often striving to demonstrate their abilities and gain peer approval through extensive social interactions35. This drive for social engagement results in larger social networks, but also increases the complexity and unpredictability of social interactions, raising their risk of engaging in antisocial behavior. Thus, this study identifies the number of good friends as a gender-specific factor influencing antisocial behavior, particularly among adolescent boys.

Adolescents from different residential areas encounter various disparities during their growth and development. In comparison to urban areas, rural regions, characterized by limited economic development and lower household incomes, often struggle to meet children’s material needs. This material deprivation can lead rural adolescents to develop a heightened sense of inferiority36,37, which, over time, increases their vulnerability to mental health issues. Additionally, parents in rural areas generally have lower educational levels, which impedes their ability to engage in meaningful communication with their children. As a result, they may struggle to understand their children’s thoughts and emotional needs in a timely manner38. Furthermore, many rural parents work away from home, leading to a significant lack of parental supervision and emotional support39. This absence of necessary behavioral guidance and emotional backing makes rural adolescents more susceptible to confusion regarding their growth and external negative influences, which can contribute to an increased likelihood of antisocial behavior due to the lack of proper guidance. Consequently, as the level of residential area decreases, the probability of antisocial behavior among adolescents rises, a finding consistent with this study. However, prior research has overlooked the role of gender. Boys, in particular, tend to have stronger self-esteem and a greater desire for respect from others40. As a result, poor living conditions are more likely to create a significant psychological gap for boys, triggering negative emotions. Additionally, boys tend to form more complex and expansive social networks than girls34. However, due to the relatively low cultural standards in some rural areas41, the social environment in which rural boys find themselves is often suboptimal, increasing their risk of engaging in antisocial behavior. Furthermore, due to weaker parental control and the physiological influence of boy hormones and the Y chromosome, boys exhibit a stronger tendency for emotional outbursts. With less emotional regulation and poorer self-control, they are more prone to antisocial behavior42. Therefore, the current place of residence as a specific influencing factor for antisocial behavior, particularly among adolescent boys.

Engage in regular physical activity has been identified as a protective factor against antisocial behavior43, as it lowers cortisol levels and increases the secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), thereby enhancing inhibitory control over the brain’s emotional centers44. Additionally, the competitive and combative nature of physical activities provides an effective outlet for the expression of negative emotions45, which subsequently reduces the likelihood of antisocial behavior. Building on this conclusion, further research has shown that, compared to adolescent girls, boys—due to higher levels of boy hormones—possess greater muscle strength and endurance46, enabling them to perform better and engage more actively in physical exercise, which results in a stronger sense of achievement. Furthermore, physical exercise meets their social needs. During exercise, the production of neurotransmitters such as endorphins47 and dopamine48 generates feelings of pleasure and satisfaction, reinforcing their enjoyment of physical activity. Consequently, boys tend to engage in more frequent, intense, and prolonged physical exercise49, which contributes to a reduction in antisocial behavior. Therefore, engage in regular physical activity is a specific influencing factor for antisocial behavior in adolescent boys.

Better family economic condition can enhance adolescents’ current and future development through interventions such as cognitive restructuring and the cultivation of positive psychological traits50. However, it is important to note that families with more favorable economic condition tend to exhibit overprotective parenting tendencies51. Under this parenting style, children are more likely to develop self-centered personality traits, making it difficult for them to establish healthy interpersonal relationships. Moreover, parents in such families often have demanding work schedules, which results in insufficient attention and companionship for their children. This lack of emotional support may lead to feelings of insecurity and alienation, thereby increasing the risk of psychological symptoms such as depression. Furthermore, families with better economic condition have greater access to digital devices, facilitating children’s exposure to complex and diverse online content52, including harmful material. As a result, better family economic conditions may contribute to the emergence of antisocial behavior, consistent with the findings of this study. Additionally, this study examines gender differences. Compared to boys, girls are more likely to experience overprotective parenting, which can foster characteristics such as dependency and moodiness53. This makes girls more prone to exhibiting aggressive behaviors in response to setbacks and negative evaluations. Furthermore, girls at this stage are generally more sensitive, empathetic, and introverted, making them more susceptible to feelings of loneliness due to long-term emotional neglect. Consequently, a lack of family emotional support may lead to anxiety, low self-esteem, and other negative psychological states54, contributing to an increase in antisocial behavior. Thus, family economic condition as a specific influencing factor for antisocial behavior in adolescent girls.

This study has several limitations: (1) Data collection relied on self-reported questionnaires, which may introduce response bias. (2) The cross-sectional design precludes the examination of temporal relationships and causal mechanisms between variables. (3) The study’s scope was limited, as it did not include factors such as early life experiences55 and pathological conditions56, which may reduce the comprehensiveness of the results. (4) The sample was confined to a specific age group of high school students, thus failing to capture the variability in behavioral patterns across different stages of adolescence. Consequently, future research should address the following improvements: (1) Incorporating objective behavioral monitoring data alongside self-reports for cross-validation, thereby minimizing single-source bias. (2) Employing longitudinal cohort designs to explore gender-differentiated trajectories of antisocial behavior. (3) Expanding the range of potential influencing factors to identify additional core determinants of adolescent antisocial behavior. (4) Conducting subgroup analyses across different stages of adolescence to identify critical windows and develop age-specific intervention strategies.

Conclusion

This study identifies six key factors influencing adolescent antisocial behavior, including parental educational expectations and smoking behavior, and highlights gender-differentiated drivers within the underlying mechanisms. These findings provide a scientific basis for clinical and educational institutions to prioritize interventions more effectively. Furthermore, by analyzing gender-specific pathways, the study supports the development of tailored intervention strategies, thus avoiding the limitations of a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Based on these results, the study suggests that parents should adjust their expectations appropriately, enhance monitoring of their children’s psychological well-being, and guide adolescents in quitting smoking. For boys, it is crucial to focus on the quality of social interactions, improve their ability to identify high-risk social situations, and encourage regular physical activity. At the policy level, efforts should focus on bridging the behavioral risk gap between rural and urban areas by optimizing the allocation of resources in rural settings. For girls, families with higher economic status should adopt supportive companionship strategies to foster autonomous decision-making and ensure emotional security. This approach will help reduce the conflict between excessive psychological dependence and behavioral resistance, prevent compensatory behaviors due to overprotection, and promote regular physical exercise.

Data availability

The data is stored in the Database of Youth Health (DYH) in National Population Health Data Center. (https://www.ncmi.cn/phda/dataDetails.do?id=CSTR:17970.11.A0031.202107.209.V1.0).

References

Brennan, C., Deegan, A., Bohan, C. & Smyth, S. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of single-case group contingency interventions targeting prosocial and antisocial behavior in school children. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. https://doi.org/10.1177/10983007241235865 (2024).

Chaby, L. E. et al. Repeated stress exposure in mid-adolescence attenuates behavioral, noradrenergic, and epigenetic effects of trauma-like stress in early adult male rats. Sci. Rep. 10, 17935. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74481-3 (2020).

Qu, Y. Stereotypes of adolescence: Cultural differences, consequences, and intervention. Child Develop. Perspect. 17, 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12489 (2023).

Anderson, C. A. & Carnagey, N. L. Violent Evil and the General Aggression Model. The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (2004).

Li, X. et al. Mediating effects of academic self-efficacy and depressive symptoms on prosocial/antisocial behavior among youths. Prev. Sci. 25, 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01611-4 (2024).

Gubbels, J., Assink, M. & van der Put, C. E. Protective factors for antisocial behavior in youth: What is the meta-analytic evidence?. J. Youth Adolesc. 53, 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01878-4 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Schizophrenia mediating the effect of smoking phenotypes on antisocial behavior: A Mendelian randomization analysis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14430 (2024).

Marzan, M., Callinan, S., Livingston, M. & Jiang, H. Alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking and the perpetration of antisocial behaviours in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 235, 109432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109432 (2022).

Gorrell, L. et al. The effect of outdoor play, physical activity, and screen time use on the emotional wellbeing of children and youth during a health crisis. Leis. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2024.2335930 (2024).

Rowe, R. Commentary: The potential of sleep research to contribute to our understanding on antisocial behaviour—A reflection on Brown, Beardslee, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman (2022). J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 64, 329–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13712 (2023).

Acland, E. L. et al. Polygenic risk and hostile environments: Links to stable and dynamic antisocial behaviors across adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942400004X (2024).

Torres-Soto, N.-Y. et al. Home habitability, perceived stress and antisocial behaviour (Habitabilidad de la vivienda, estres percibido y conducta antisocial). Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2022.2158592 (2023).

Celik, I. Revisiting general strain theory: Studying the predictors of adolescents? antisocial behavior in Vestland county, Norway. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 139, 106556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106556 (2022).

Gresko, S. A. et al. An examination of early socioeconomic status and neighborhood disadvantage as independent predictors of antisocial behavior: A longitudinal adoption study. PLoS ONE 19, e0301765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301765 (2024).

Mancke, F., Herpertz, S. C. & Bertsch, K. Correlates of aggression in personality disorders: An update. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20, 53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0929-4 (2018).

Tataw, D. B. Individual and interpersonal factors associated with youth antisocial behavior among a low income, immigrant, and ethnic urban youth sample. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 50, 784–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2024.2353335 (2024).

Acar, I. H. et al. Examining the roles of child temperament and teacher-child relationships as predictors of Turkish children’s social competence and antisocial behavior. Curr Psychol 39, 2231–2245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9901-z (2020).

Sundberg, N. D., Latkin, C. A., Farmer, R. F. & Saoud, J. Boredom in young adults: Gender and cultural comparisons. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 22, 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022191222003 (1991).

Yang, Y. et al. Does physical activity affect social skills and antisocial behavior? The gender and only child status differences. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1502998 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Study of cardiovascular disease prediction model based on random forest in eastern China. Sci. Rep. 10, 5245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62133-5 (2020).

Shandong university. adolescent health topics database. https://doi.org/10.12213/11.A0031.202107.209.V1.0 (2021).

Zhang, S. F. et al. A dataset on the status quo of health and health-related behaviors of chinese youth: A longitudinal large-scale survey in the secondary school students of Shandong province. Chin Med Sci J. 37(1), 60–66 (2022).

Derogatis, L. & Cleary, P. Confirmation of dimensional structure of Scl-90—study in construct-validation. J. Clin. Psychol. 33, 981–989. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(197710)33:4%3c981::AID-JCLP2270330412%3e3.0.CO;2-0 (1977).

Li, Y., Hu, T., Ge, T. & Auden, E. The relationship between home-based parental involvement, parental educational expectation and academic performance of middle school students in mainland China: A mediation analysis of cognitive ability. Int. J. Educ. Res. 97, 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.08.003 (2019).

Li, J., Xue, E. & You, H. Parental educational expectations and academic achievement of left-behind children in China: The mediating role of parental involvement. Behav. Sci. 14, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/BS14050371 (2024).

Pérez-Albéniz, A., Lucas-Molina, B. & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Parental support and gender moderate the relationship between sexual orientation and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Psicothema 35, 248–258. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2022.325 (2023).

Xiao, C., Zhou, C., Jiang, J. & Yin, C. Neural circuits and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediate the cholinergic regulation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons and nicotine dependence. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 41, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-019-0299-4 (2020).

Clay, J. M. et al. Associations between COVID-19 alcohol policy restrictions and alcohol sales in British Columbia: Variation by area-based deprivation level. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 84, 424–433. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.22-00196 (2023).

Bang, I. et al. Secondhand smoking is associated with poor mental health in Korean adolescents. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 242, 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.242.317 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Parent and friend emotion socialization in early adolescence: Their unique and interactive contributions to emotion regulation ability. J. Youth Adolesc. 53, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01855-x (2024).

Thompson, A., Smith, M. A., McNeill, A. & Pollet, T. V. Friendships, loneliness and psychological wellbeing in older adults: A limit to the benefit of the number of friends. Ageing Soc. 44, 1090–1115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X22000666 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Do number of smoking friends and changes over time predict smoking relapse? Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. J. Subst. Abuse Treatment 138, 108763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108763 (2022).

Fei, G. et al. The contagious spread of bullying among Chinese adolescents through large school-based social networks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 158, 108282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108282 (2024).

Potter, J. R. & Yoon, K. L. Interpersonal factors, peer relationship stressors, and gender differences in adolescent depression. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01465-1 (2023).

Nielson, M. G., Jenkins, D. L. & Fraser, A. M. Too hunky to help: A person-centered approach to masculinity and prosocial behavior beliefs among adolescent boys. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 40, 2763–2785. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221084697 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. A man-made divide: Investigating the effect of urban–rural household registration and subjective social status on mental health mediated by loneliness among a large sample of university students in China. Front. Psychol. 13, 1012393. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1012393 (2022).

McDaniel, C. E., Hall, M., Markham, J. L., Bettenhausen, J. L. & Berry, J. G. Urban–rural hospitalization rates for pediatric mental health. Pediatrics 151, e2023061256. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-061256 (2023).

Lin, K., Ramos, S. & Sun, J. Urbanization, self-harm, and suicidal ideation in left-behind children and adolescents in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 37, 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000927 (2024).

Jia, Y. et al. Bidirectional longitudinal relationships between beliefs about adversity, teacher-student relationships and academic engagement of left behind children. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 28, 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-024-09956-6 (2025).

Peng, C. et al. Father-child attachment and externalizing problem behavior in early adolescence: A moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 41, 4997–5010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03041-x (2022).

Liu, J., Cai, M. & Cui, Y. Assistance at the starting line: Rural education competition and rural student development. High Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-025-01428-w (2025).

Liu, L. et al. Association of Y-linked variants with impulsivity and aggression in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder of Chinese Han descent. Psychiatry Res. 252, 185–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.055 (2017).

Roman, P. A. L., Del Castillo, R. M., Sanchez, J. S. & Montilla, J. A. P. Analysis of the influence of sports practice on prosocial and antisocial behaviour in a contemporary Spanish adolescent population. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 54, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.7352/IJSP.2023.54.016 (2023).

Oyovwi, M. O., Ogenma, U. T. & Onyenweny, A. Exploring the impact of exercise-induced BDNF on neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 52, 140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-025-10248-1 (2025).

Rocliffe, P. et al. The impact of typical school provision of physical education, physical activity and sports on adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 9, 339–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00220-0 (2024).

Hamilton, B. et al. Strength, power and aerobic capacity of transgender athletes: a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-108029 (2024).

Carrasco Paez, L. & Martinez-Diaz, I. C. Training vs. competition in sport: State anxiety and response of stress hormones in young swimmers. J. Hum. Kinet. 80, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2021-0087 (2021).

Humińska-Lisowska, K. Dopamine in sports: A narrative review on the genetic and epigenetic factors shaping personality and athletic performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 11602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252111602 (2024).

Song, D. et al. The effect of college students’ school sports policy attitudes on physical quality: The mediating role of physical exercise and gender difference. Curr. Psychol. 43, 21448–21459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05876-y (2024).

Jeong, T. Family economic status and vulnerability to suicidal ideation among adolescents: A re-examination of recent findings. Child Abuse Negl. 146, 106519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106519 (2023).

Liu, X. & Tong, L. J. Who influences the career choices of secondary vocational students——A study based on the relationship between family economic status, parental rearing styles and students’ career development. Vocat. Tech. Educ. 42, 52–59 (2021).

Pan, Y., Zhou, D. & Shek, D. T. L. After-school extracurricular activities participation and depressive symptoms in Chinese early adolescents: Moderating effect of gender and family economic status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074231 (2022).

Kerr, B. A., Vuyk, M. A. & Rea, C. Gendered practices in the education of gifted girls and boys. Psychol. Sch. 49, 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21627 (2012).

Bell, L. J., John, O. P. & Hinshaw, S. P. ADHD symptoms in childhood and big five personality traits in adolescence: A five-year longitudinal study in girls. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 52, 1369–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-024-01204-x (2024).

Piquero, A. R. et al. A meta-analysis update on the effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. J. Exp. Criminol. 12, 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9256-0 (2016).

Moffitt, T. E. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all adolescents, who participated in this study voluntarily.

Funding

The study was supported by The National Social Science Fund of China (21BTY054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z.S.:Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Y.G.:Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition. L.Y. Z.:Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software. Y.K.Y.:Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft. L. C.:Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Y.N.H.:Writing—review and editing. X.R.Y.:Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration. S.Q. Z.:Supervision, Writing—original draft. S.M.:Data curation, Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sui, W., Gao, Y., Zhao, L. et al. Analysis of the significance and gender differences in the factors influencing antisocial behaviors among adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 14933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99212-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99212-4