Abstract

To verify whether the recently synthesized nucleoside, 8-(4-Trifluoromethoxy)benzylamino-2′-deoxyadenosine, can sensitize tumorous cells to X-rays, radiolytic and in vitro studies have been conducted. Molecular modeling demonstrated that excess electrons should lead to efficient dissociative electron attachment (DEA) to dA-NHbenzylOCF3 resulting in a radical product that can potentially damage DNA. The computationally predicted DEA process was confirmed via stationary radiolysis of a dA-NHbenzylOCF3 water solution followed by LC-MS analysis of the obtained radiolytes. Moreover, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was tested against its cytotoxicity and clonogenicity. We showed that the modified nucleoside is not cytotoxic to PC3, MCF-7, and HaCaT cell lines. Additionally, the clonogenic test exhibited a statistically significant radiosensitization of PC3 and MCF-7 cells to X-rays. On the other hand, flow cytometry assays demonstrated that the action of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 is related to its influence on the cell cycle rather than the level of DNA double-strand breaks induced by ionizing radiation. Our findings indicate that the compound enters the cell and predominantly localizes in the cytoplasm, with a notable amount also detected in the nucleus. Moreover, we established that the compound is not phosphorylated by cellular kinases nor integrated into genomic DNA by the replication machinery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modified nucleosides like 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) sensitize DNA to ionizing radiation-induced damage1,2. Although ionizing radiation (IR) is one of the most commonly used modalities in anti-cancer treatment,3 IR’s mutagenic aftereffect reaction,4 and so-called oxygen effect5,6 (related to hypoxia of solid tumors) makes cancerous cells resistant to IR. Hence, the importance of developing an efficient radiosensitizer is difficult to overestimate. The BrdU mentioned above increases the sensitivity of cancer cells by more than three times compared to the control7. Unfortunately, BrdU is swiftly metabolized due to efficient hepatic dehalogenation by thymidylate synthetase which shortens its in vivo half-life to a couple of minutes,8,9 which prevents achieving therapeutic levels of the radiosensitizers in cancer cells in vivo. Thus, despite almost ideal in vitro radiosensitizing activity, BrdU is useless as a radiosensitizer10 due to its fast metabolism. Therefore, efforts to design radiosensitizers resistant to metabolism, which would guarantee their cellular delivery in an intact form to cancer tissue are worth undertaking.

The radiosensitizing action of some modified nucleosides is related to their reaction with solvated electrons11. Interaction between the latter and DNA is inconsequential as far as the damage of biopolymer is concerned12,13. It is worth noticing, however, that solvated electrons are produced during water radiolysis in an amount similar to that of hydroxyl radicals, the major DNA-damaging species4. Therefore, the involvement of hydrated electrons in DNA damage would significantly increase the efficiency of radiotherapy. Indeed, when working as a radiosensitizer, BrdU and similar nucleosides undergo DEA, which produces reactive radicals localized to nucleosides and capable of damaging DNA12. Thus, when designing a new radiosensitizer one has to introduce to the nucleoside a substituent that increases its electron affinity and makes the modified nucleoside prone to the dissociative electron attachment (DEA) process14,15.

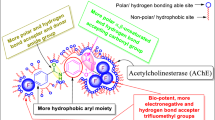

Most of the proposed to date nucleoside modifications are based on pyrimidine skeleton16. Pyrimidine derivatives seem to be a natural choice since pyrimidine nucleosides possess higher electron affinities than purine ones17 and one of the first radiosensitizers 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuracil is a uracil derivative. However, there are no fundamental reasons to exclude purine nucleosides from the set of potential radiosensitizers. Indeed, we demonstrated in the past that trimeric oligonucleotides labeled with 8-bromo-adenosine or 8-bromo-guanosine are prone to DEA under ultra-high vacuum18,19. In this communication, we report on another adenosine derivative, 8-(4-trifluoromethoxy)benzylamino-2’-deoxyadenosine (dA-NHbenzylOCF3) with radiosensitizing properties.

Results and discussion

Theoretical calculations

Before synthesizing the title compound, quantum chemical calculations on DEA profiles were carried out. In brief, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 degradation induced by the attachment of an electron was described at the density functional theory (DFT) level using the B3LYP functional20,21,22 and 6–31 + + G(d, p) basis set23,24. The computational model was simplified by replacing the deoxyribose in the dA-NHbenzylOCF3 molecule with a methyl group. This simplification was successfully applied to many previously studied systems25,26,27,28,29. Finally an implicit solvent model (PCM,30 water) was used to account for the aqueous environment.

DEA profile for dA-NHbenzylOCF3 calculated at the B3LYP/6–31 + + G(d, p) level. The charge and multiplicity of individual species are indicated in square brackets. Gray color-carbon, blue color-nitrogen, red color-oxygen, white color-hydrogen, light blue color-fluorine atoms. The inset shows a molecular fragment where the cleavage of the C-N bond occurs due to DEA.

Figure 1 depicts energetic characteristics (in the free energy scale) calculated for the DEA path involving dA-NHbenzylOCF3. Electron attachment was predicted to be a highly favorable process with the thermodynamic stimulus of c. 38 kcal/mol (Fig. 1). For unsubstituted species, i.e. for 8-benzylamino-2’-deoxyadenosine electron affinity is smaller and amounts to c. 36 kcal/mol which agrees with the general influence of electron-withdrawing substituent on electron attachment. Moreover, the thermodynamic barrier that separates radical anion, a product of electron attachment, from the DEA-produced product complex (see Fig. 1) assumes a negative value (-0.5 kcal/mol; Fig. 1) which suggests that the radical anion is unstable and dissociates immediately after electron attachment. The computational model predicts the cleavage of the C-N bond between the substituted benzyl fragment and the 8-aminoadenine one (see Fig. 1). Bond dissociation is governed by the electron affinities of the two fragments. Indeed, at the B3LYP/6–31 + + G(d, p)/PCM level adiabatic electron affinities of substituted benzyl and 8-aminoadenine radicals are equal to 3.16 and 4.19 eV, respectively. The formation of the product complex is associated with a favorable free energy of reaction equal to c. -30 kcal/mol (see Fig. 1). Altogether, these computational arguments imply an efficient DEA for dA-NHbenzylOCF3.

To confirm the computational findings, we synthesized dA-NHbenzylOCF3 by reacting 8-bromo-2′-deoxyadenosine with 4-(trifluoromethoxy)benzylamine in a methanolic solution (see Fig. 2). The compound was purified with flash chromatography (for purity see Fig S1), and its identity was confirmed by 1H-NMR, C-NMR, and HRMS (for NMR and MS spectra, see the Supporting Information, Figs S2–S4).

The first reason to propose this at first glance exotic derivative was practical, i.e. the ease of synthesis of adenine modification. Namely, we used the method described by Vivet-Boudou et al.31 which utilizes a reaction between 8-bromo-2′-deoxyadenosine and the respective amine giving 2’-deoxyadenosine substituted at 8 position. Since a radiosensitizing nucleoside should bind the excess electron14, we also decided to use the strong electron-withdrawing -OCF3 substituent in the amine moiety (note, that benzylamine substituted with -OCF3 is commercially available).

Stationary radiolysis

The radiolysis of water solution of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was conducted with the addition of tert-butanol as an ·OH free radical scavenger and phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7) which corresponds to physiological level of pH. Samples were irradiated with a dose of 500 Gy with using of a CellRad X-ray cabinet. The applied dose of ionizing radiation leads to the degradation of the synthesized compound and produces a product with a retention time of 3.49 min (see Fig. 3). The radiolyte was analyzed using LCMS and LCMS/MS techniques. These analyses unambiguously demonstrated that the observed product is 8-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine. The MS signal registered at m/z = 267.1797 (recorded in positive ionization mode; see Fig S5 in the Supporting information) corresponds to the protonated form of 8-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine, and the way it is fragmented in the MS/MS experiment (the cation of m/z = 151.0891 is due to the protonated 8-aminoadenine that originates from the fragmentation of the protonated 8-amino-2′-deoxyadenosine; see Fig S6 in the Supporting Information) is consistent with 8-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine as the radiolysis product. Note that the radiolitic degradation remains in full agreement with the quantum chemical prediction. As indicated in Fig. 1 electron attachment to the studied nucleoside leads to a barrier-free cleavage of the C-N bond resulting in the 8-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine anion and 4-(trifluoromethoxy)toluene (benzylOCF3) radical. Under the experimental conditions, the former species is easily protonated, and in the form of protonated 8-amino-2′-deoxyadenosine determined in the LCMS analysis. The latter radical product is probably stabilized by attaching a free hydrogen atom coming from water radiolysis or abstracting a hydrogen atom from the tert-butanol molecule, ultimately forming benzylOCF3, which is inert toward electrospray ionization. Its absorption is also quite weak in the entire UV region, which makes the identification of benzylOCF3 demanding. However, as indicated by Fig. 3, HPLC UV signals related to both DEA stable products, 8-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine and benzylOCF3, are observed in the RP-HPLC chromatogram (Fig. 3, middle panel).

Cytotoxicity analysis

It is important to note that potential radiosensitizers can be considered suitable for in vitro application only with their low cytotoxicity, as they should become toxic only after exposure to ionizing radiation. Therefore, we performed the widely accepted cell viability test, namely the MTT assay32. Three cell lines were chosen for this test: PC3, a human prostate cancer cell line, which serves as a model for the most common cancer in males; MCF-7, a human breast cancer cell line representing the most common cancer in females; and HaCaT, a healthy, immortalized human keratinocyte cell line.

The MTT test (see Fig. 4) showed that for the PC3 line, the reduction in cell viability generated by dA-NHbenzylOCF3 compared to cell viability in the control variant (cells not treated with the tested derivative) is statistically significant (p < 0.0001) at a concentration of 100 µM after both 48 and 72 h of incubation and at a concentration of 20 µM after 72 h of incubation (statistically significant (p < 0.01)). For 48-hour incubation, the 100 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3 solution reduces cell viability to 86.3 ± 3.4%, and for 72-hour incubation to 80.8 ± 3.2%, respectively. While a concentration of 20 µM reduces cell viability to 88.5 ± 0.2%. In the case of the MCF-7 cell line, a statistically significant reduction in viability is observed in a concentration of 100 µM of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 at both incubation times. For 48-hour incubation, the 100 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3 solution reduces cell viability to 91.9 ± 1.2% (p < 0.5), and for 72-hour incubation to 87.5 ± 1.3% (p < 0.0001), respectively. In contrast, no statistically significant decrease in MCF-7 cell viability was observed in the range of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 concentrations tested. Therefore, it can be concluded that the tested compound is less toxic against breast cancer cells than prostate cancer cells. Relative to cells of the HaCaT line, the reduction in viability generated by the tested compound is also statistically significant at a concentration of 100 µM after both 48 (p < 0.001) and 72 h (p < 0.0001) of incubation. For 48-hour incubation, a solution of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 at a concentration of 100 µM reduces cell viability to 84.2 ± 4.1%, and for 72-hour incubation to 76.3 ± 5.1%, respectively.

The viability of (a) PC3, (b) MCF-7 and (c) HaCaT cells after 48 h and 72 h treatment with dA-NHbenzylOCF3. The results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. A statistically significant difference is present between treated cultures compared with control (culture treated with vehicle), ****p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.5.

Clonogenic assay

The clonogenic assay is the gold standard for assessing cell survival in vitro following radiation exposure32. It measures the ability of a single cell to grow into a colony after being exposed to a defined dose of radiation. This assay was conducted to assess the effect of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 on the survival and colony formation ability of PC3 prostate cancer cells and MCF-7 breast cancer cells following exposure to ionizing radiation. Incubation with the dA-NHbenzylOCF3 derivative reduced the survival of prostate cancer cells from 88.8% ± 1.3 to 73.9% ± 0.7% for a dose of 1 Gy, from 61.1% ± 0.3 to 53.3% ± 1.8% for a dose of 3 Gy, and from 49.5% ± 1.1 to 37.1% ± 0.5% for a dose of 4 Gy. However, in the context of MCF-7 cells, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 reduced the survival from 87.5 ± 0.6% to 84.4 ± 0.9% for a dose of 1 Gy, from 68.5% ± 0.9 to 64.3% ± 0.3% for a dose of 3 Gy, and from 56.4% ± 0.6 to 47.3% ± 0.5% for a dose of 4 Gy. Figure 5 shows the survival fractions of PC3 cells (Fig. 5a) and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 5b) irradiated with different doses of ionizing radiation pre-incubated with the tested compound. Based on survival curves, the parameters for cellular radiosensitivity, such as α (coefficient for linear killing), and β (coefficient for quadratic killing) values, were calculated by a fitting using the linear–quadratic model. Average α and β values were as follows: 0.118 and 0.016 (untreated PC3 cells), 0.247 and − 0.004 (PC3 cells treated with 20 µM of dA-NHbenzylOCF3), 0.115 and 0.006 (untreated MCF-7 cells), 0.177 and − 0.0007 (MCF-7 cells treated with 20 µM of dA-NHbenzylOCF3). Since, from a radiobiological point of view, the negative values of the β parameters are not realistic, the fitting for curves corresponding to the survival of dA-NHbenzylOCF3-treated cells has been performed with β forced to zero. Such a procedure results in a slight change of α values: 0.246 for PC3 cells and 0.181 for MCF-7 cells. Radiosensitization by the studied derivative is mainly due to an increase in the α linear parameter, which suggests an increase in the number of directly lethal events by dA-NHbenzylOCF333,34. It should be also noticed that the α value is enhanced by a factor of 2.1 (the ratio of α for curve corresponding to cells treated with dA-NHbenzylOCF3 and untreated one) in case of PC3 line and by 1.5 for MCF-7 line. Additionally, the dose enhancement factor (DEF), defined as the increase in the effectiveness of the radiation dose in the presence of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 compared to irradiation without the radiosensitizer, was determined to be 1.30 and 1.21 for PC3 and MCF-7 cell line, respectively (DEF = ID50(− treatment)/ID50(+ treatment)), where ID50 means radiation dose causing 50% growth inhibition35. The above results prove that the titled derivative has a stronger impact on cells from the PC3 line than the MCF-7 line.

Dose-response curves for reduced survival of (a) PC3 cells and (b) MCF-7 cells following dA-NHbenzylOCF3 dose-dependent treatment of cultures non-treated or treated with dA-NHbenzylOCF3 (20 µM). The results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Histone H2A.X phosphorylation

To rationally improve the radiosensitizing ability of the tested compound, knowledge concerning the mechanism of radiosensitization seems to be indispensable. Double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) are among the most toxic forms of damage and constitute the primary lethal injury caused by ionizing radiation. Moreover, modified nucleosides, like BrdU, after incorporation into DNA and activation by attachment of solvated electrons lead to DNA strand breaks. Thus, their basic mode of action is related to the increased formation of DNA strand breaks. Hence, we analyzed the process of H2A.X histone phosphorylation, which is a marker of DSBs,37 using cytometric analysis. Figure 6 shows the results of the experiment for both PC3 and MCF-7 cell lines treated with dA-NHbenzylOCF3 and/or irradiated with 8 Gy (for dot plots and gating strategy see Fig S7 in the Supporting Information). It is noted that dA-NHbenzylOCF3 causes no effect on H2A.X phosphorylation level, compared to the control variant, as well as combining this compound with irradiation did not show a statistically significant effect in comparison to the irradiation variant in PC3 (see Fig. 6a) and MCF-7 (see Fig. 6b). Only irradiation alone shows the statistical significance (p < 0.0001) effect of appearing histone H2A.X phosphorylation and double-strand break formation, compared to the control variant in both lines. This indicates that the radiosensitizing mechanism of action of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 is not associated with the occurrence of DNA double-strand breaks in cancer cells.

Analysis of H2A.X histone phosphorylation in (a) PC3 and (b) MCF-7 cells by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments conducted in triplicate. The level of H2A.X phosphorylation represents the percentage of the cell population with fluorescence exceeding the gating threshold for the H2A.X marker.

Cell cycle analysis

To further elucidate the radiosensitizing mechanism of dA-NHbenzylOCF3, we investigated the effect of the compound on cell cycle progression in PC3 and MCF-7 cells using flow cytometry. It is well-known that ionizing radiation interferes with the cell cycle, slowing the progression of particular cell-cycle phases38. Moreover, cells are most sensitive to IR in the G2/M phases, less sensitive in the G1 phase, and least sensitive during the latter part of the S phase39. Thus, a radiosensitizer can work by modulating the cell cycle to increase the population of cells in the most radio-responsive phases. Analysis of the cell cycle in PC3 cells (see Fig. 7a) revealed that treatment with 20 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3, combined with 8 Gy of ionizing radiation, reduced the fraction of cells in the G0/G1 phase from 47.8% ± 1.1 to 36.3% ± 3.3% and increased the proportion of cells in the most radiosensitive G2/M phase from 46.1% ± 1.2 to 56.8% ± 2.8%, compared to radiation alone. A similar effect was observed in the MCF-7 cell line (see Fig. 7b), where the combination therapy decreased the G0/G1 cell population from 43.3% ± 2.4 to 41.7% ± 0.9% and increased the G2/M phase population from 43.8% ± 0.2 to 48.4% ± 0.1%, compared to radiation alone. Furthermore, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 alone did not significantly affect the cell cycle compared to the control in either cell line. These results suggest that the compound exhibits a stronger influence on cell cycle regulation in PC3 cells than in MCF-7 cells.

Quantitative analysis of cell cycle distribution for (a) PC3 and (b) MCF-7 cell lines (for histograms see Fig S8 in Supporting Information). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance for differences in G2/M phase cell populations between the specified groups is indicated as **** p < 0.001, and ** p < 0.01.

Further verification of the radiosensitization mechanism

To gain a deeper insight into the mechanism of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 radiosensitivity, we decided to verify whether the compound enters the cell, where it accumulates, whether it is phosphorylated by cellular kinases, and whether it is incorporated into genomic DNA.

Localization of radiosensitizer in the cell

To verify if the nucleoside enters the cell and to learn its subcellular localization a cell fractionation assay (for the protocol, see the Cell fractionation assay section below) was performed to isolate the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Both fractions were divided into two parts: one was directly analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer (LC-MS), and the other was digested into nucleosides using the Nucleoside Digestion Mix Kit (New England Biolabs, US) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (for details see Methods: The Nucleoside digestion section). Such an approach allowed us to determine the total pool of the derivative in the nucleoside form (in case the derivative was phosphorylated and was present inside the cell in the mono-, di- or triphosphate form). The obtained results confirmed the presence of a peak corresponding to dA-NHbenzylOCF3 in both the cytoplasmic (see Fig. 8a) and nuclear (see Fig. 8b) fractions, indicating that the derivative is present in both cytoplasm and nucleus which proves that the studied radiosensitizer enters the cell.

Based on the peak areas corresponding to dA-NHbenzylOCF3 in both fractions and in the standard nucleoside solution at a concentration of 10− 4 M, as well as knowing the final volume of both fractions, the molar ratio of the derivative present in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions was estimated. For a concentration of 20 µM, the molar ratio of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 in the cytoplasmic to nuclear fraction was 26:1, while at a concentration of 100 µM, it was 22:1. These results demonstrate that a higher concentration of the derivative was observed in the cytoplasmic fraction, suggesting that the compound primarily localizes in the cytoplasm.

Nucleosides may undergo at least partial phosphorylation under cellular conditions. Therefore, the presence of mono-, di-, and tri-phosphorylated forms of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was tested by using the selected-ion monitoring mode of MS. However, no masses corresponding to the phosphorylated dA-NHbenzylOCF3 were detected. To further validate this observation, cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were subjected to the action of the mentioned above Nucleoside Digestion Mix Kit which converts nucleotides to nucleosides. Subsequently, the fractionated and digested samples were analyzed using the XIC (eXtracted Ion Chromatogram) mode of MS. The results showed that the peak area of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 remained unchanged compared to the undigested sample, confirming thus that the compound is present in the cell exclusively in its unphosphorylated form.

Radiosensitizer incorporation into cellular DNA

The lack of phosphorylated forms of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 suggests that it is not incorporated into cellular DNA. To confirm this supposition, we decided to digest DNA down to nucleosides (for details see the DNA digestion section of Methods). In order to determine the degree of incorporation of the derivative into genomic DNA, the nucleoside solution obtained after DNA digestion was analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (analysis method: isocratic elution with 0% phase B for 10 min, followed by a linear gradient from 0 to 100% phase B between 10 and 30 min). Additionally, a standard solution containing dA, dG, dC, T and dA-NHbenzylOCF3 at a concentration of 10− 4 M of each was prepared for HPLC analysis. The results obtained (see Fig. 9) indicate the absence of peak corresponding to dA-NHbenzylOCF3 (retention time: 19.67 min in the reference mixture) in DNA obtained from the cells incubated with the tested compound. Thus, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 is not incorporated into the genomic DNA of PC3 cancer cells (at least to the degree that overcomes the HPLC detection limit). Additionally, the samples were analyzed using LC-MS in the selected ion mode, where the MS detector was set to search for the cation with m/z equal to 441, corresponding to the mass of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 in positive ionization mode. As a reference, a mixture containing dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was used. The specified mass was not observed in the treated samples, further confirming the results obtained with the HPLC analysis.

Conclusions

In summary, we chemically synthesized a new derivative of 2’-deoxyadenosine with a (4-Trifluoromethoxy)benzylamine substituent at its 8-position. The electron-withdrawing effect of this substituent increases the nucleoside’s electron affinity, facilitating the electron attachment process. Moreover, as indicated by the computational DEA profile, when the radical anion forms, it dissociates without a kinetic barrier into the 8-aminoadenine anion. This theoretical finding is corroborated by stationary radiolysis, which demonstrates the same bond-breakage in the substituent. In vitro studies conducted on three cell lines reveal low toxicity of the modified nucleoside, which is an essential requirement for any radiosensitizer with practical applications. In contrast to brominated/iodinated nucleosides like BrdU/IdU, dA-NHbenzylOCF3 does not increase the number of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in irradiated cells, as indicated by flow cytometry analysis of H2A.X histone phosphorylation. It appears that the primary mode of action of the studied nucleoside is partially related to cell cycle modulation. Indeed, using flow cytometry to analyze the cell cycle, we observed a statistically significant increase in the population of cells in the radiosensitive G2/M phase. We also demonstrated that the compound enters the cell, and it accumulates mainly in cytoplasm although a significant amount of the derivative was also observed in the nucleus compartment. Additionally, we proved that that compound is neither phosphorylated by the cellular kinases nor incorporated into genomic DNA by cellular replication machinery.

To further optimize the radiosensitizing properties of such types of compounds, ongoing studies in our laboratory are focused on adenosine derivatives with other electron-withdrawing substituents in the aminobenzyl group attached to the 8 position of the nucleoside.

Methods

General methods and materials

Reagents for synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Ambeed. All reagents for maintaining the cells culture were obtained from ThermoFisher. PC3 and MCF-7 cell lines were obtained from ATCC, while cells of the HaCaT line were obtained from CLS. All cytometric tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Luminex). Purification of the sample was carried out using Flash Chromatography - Büchi FlashPure Cartridges (silica gel 40 μm irregular) on a Büchi Pure Chromatography System with an integrated UV and ELSD detector. The purity of the sample was determined by reversed-phase RP-HPLC high-performance liquid chromatography, using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 chromatograph with a diode array detector (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and a Wakopak Handy ODS analytical column (150 × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase was a system of solvents A and B, applied in a 20-minutes gradient of 0-100% phase B, where: A − 0.1% HCOOH and 0.1% ACN in water; B − 80% ACN. The volumetric flow rate of eluent was 1 mL/min. Detection was carried out at a wavelength of 280 nm. The LC/MS and LCMS/MS measurements were performed using a TripleTOF 5600+ (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) high-resolution mass spectrometer coupled to a UPLC system (Nexera X2, Shimadzu, Canby, OR, USA). NMR spectra were measured in DMSO-d6 using 500 MHz spectrometer (Varian Unity Inova).

Synthesis

To a spherical round bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer 8-bromo-2’-deoxyadenosine (0.12 g, 0.363 mmol), benzylamine-OCF3 (1.39 g, 7.26 mmol) and methanol (6 mL) were added and refluxed for 28 h. Then, the mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and purified using column chromatography (Flash system) on a solid phase. The program was set to linear gradient 0–35% of phase B, where A – methylene chloride,

B – methanol. Detection was done at 260 and 280 nm. Yield 40%. Purity confirmed by HPLC: 98% 1H NMR δH (500 MHz, DMSO- d6): 7.89 (1 H, s, CH(6)), 7.68 (1 H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, NH(19)), 7.47 (2 H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, Ar-H(22/24)), 7.30 (2 H, d, J = 8,2 Hz, Ar-H (23/25)), 6.52 (2 H, bs, NH2 (10)), 6.37 (1 H, dd, J = 9.3, 5.8 Hz, CH(14)), 5.80 (1 H, dd, J = 5.8, 4.2 Hz, OH (18)), 5.30 (1 H, d, J = 3,7 Hz, OH(16)), 4.57 (2 H, qd, J = 15.7, 5.9 Hz, CH2(20)), 4.43–4.36 (1 H, m, CH (11)), 3.93–3.86 (1 H, m, CH (13)), 3.67–3.54 (2 H, m, CH2 (17)), 2.73 (1 H, ddd, J = 12.9, 9.3, 5.8 Hz, CH 15)), 2.05 (1 H, ddd, J = 13.0, 5.9, 1.6 Hz, CH (15)); C NMR: 152.91; 151.35; 149.83; 149.11; 147.54; 147.53; 139.89; 129.37; 121.33; 117.30; 88.01; 83.61; 71.94; 62.21; 45.02; 38.23. HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd. for C17F3H20N7O4 441.14, found 441.23 [M + H]+.

Quantum chemical calculations

To simplify the model the deoxyribose moiety in dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was replaced by a methyl group. DEA profile was calculated using the fully optimized geometries of the reactants at the B3LYP level,21 employing the 6–31 + + G(d, p) basis set23. The Polarization Continuum Model (PCM) was used to mimic the solvent30. All the optimized geometries were found to be geometrically stable, as verified by harmonic frequency analysis (all force constants were positive for minima, while one and only one was negative for the first-order transition states). Additionally, the intrinsic reaction coordinate40 (IRC) procedure was used to ensure that the obtained transition state connects the proper minima. The Gibbs free energies of particular elementary reactions and activation free energies were estimated as electronic energy change between the product and substrate (or between the substrate and transition state for activation energy) corrected for zero-point vibration terms, thermal contributions to energy, the pV term and the entropy term. These terms were calculated in the rigid rotor-harmonic oscillator approximation for T = 298 K and p = 1 atm.41

All computations were carried out using Gaussian 0942 and visualized using GaussView 6.043.

Stationary radiolysis

Radiolysis of an aqueous solution of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 at a concentration of 10− 4 M was conducted with the addition of tert-butanol (30 mM) as an •OH free radical scavenger and phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7) in Eppendorf tubes. Samples were purged with argon for 3 min and subsequently irradiated with a dose of 500 Gy using a CellRad X-ray Cabinet (Faxitron, X-ray Corporation, Tucson, AZ, USA) at a dose rate of 5.81 Gy/min. The voltage and current of the X-ray tube were equal to 130 kV and 5 mA, respectively. A 0.5 mm Al filter was used.

Cell culture

PC3 and MCF-7 cell lines were obtained from ATCC, while cells of the HaCaT line were obtained from CLS. PC3 cells were cultured in F-12 K medium, MCF-7 cells were cultured in RPMI medium and HaCaT cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium. Each medium was supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum) and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) at a concentration of 100 U mL− 1. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The plates with cells were irradiated using a CellRad X-ray cabinet (Faxitron, X-ray Corporation, Tucson, AZ, USA). dA-benzylNHOCF3 was resuspended in DMSO for molecular biology for treatment in all cellular experiments performed.

MTT test

Cells were seeded at a density of 4000 per well into 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with the tested compound at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 100 µM or 1% DMSO as a control and incubated for 48 and 72 h. Then a solution of MTT salt (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was added at a concentration of 4 mg/mL (25 µL per well), and after 2 h of incubation the resulting product - formazan was dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance at 570 nm (with a reference wavelength of 660 nm) was measured using an EnSpire microplate reader (Perkin Elemer). The viability of control cells was taken as 100%. Experiments were performed independently three times in triplicate. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 Software, https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/.

Clonogenic assay

Cells from the PC3 and MCF-7 lines were seeded into 60-mm diameter dishes at concentration of 105 cells per dish and incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) with 20 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3 solution. After 48 h of incubation with the tested compound, the cultures were exposed to ionizing radiation (X-rays) in the dose range of 0–4 Gy. After 6 h of irradiation, cells were trypsinized and seeded at a density of 600 cells per 60 mm diameter plates. After 14 days, the resulting colonies were fixed with 6.0% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 0.5% crystal violet. The stained colonies were evaluated and counted using a GelCount Oxford Optronix automated colony counter. The experiment was conducted in triplicate. The control consisted of cultures not exposed to ionizing radiation. The survival curves were fitted using the linear-quadratic model with the use of GraphPad Prism 7 Software (SF = exp(-1·(α·D + β·D2) where “D “is the dose and “α” and “β” are the optimized parameters). The survival data are presented in a semi-logarithmic plot of the surviving fraction against the dose.

Histone H2A.X phosphorylation

PC3 and MCF-7 cells were allocated into four groups: (i) the control group (treated with vehicle – 1% DMSO), (ii) the group treated with 20 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3, (iii) the irradiated group (8 Gy), and (iv) the group treated with 20 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3 and irradiated with 8 Gy. Following irradiation, the cells were incubated for 2 h, then dissociated using accutase solution, fixed, and permeabilized. Subsequently, the cells were stained with an Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugated antibody and analyzed using a Guava easyCyte flow cytometer (Incyte 3.3. Software, https://www.merckmillipore.com/PL/pl/20130828_204624). All procedures (fixation, permeabilization, staining) were optimized and conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (FlowCellect Histone H2A.X Phosphorylation Assay Kit, Luminex). Unirradiated and untreated controls were used to establish the threshold gating for determining the fraction of γH2A.X (H2A.X histone phosphorylated at serine 139) positive cells. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell cycle analysis

PC3 and MCF-7 cells were assigned to four groups as described in Histone H2A.X phosphorylation method. The cells were incubated with the studied compound for 48 h. The concentration of dA-NHbenzylOCF3 was determined based on preliminary studies to balance efficacy and toxicity. Cells were dissociated using accutase solution 24 h after irradiation, fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide (Guava Cell Cycle Reagent, Luminex) for 30 min, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Post-staining, samples were analyzed via flow cytometry (Guava easyCyte 12, Merck Millipore). Cells were gated on a scatter plot of FSC (Forward Scatter) versus DNA to exclude cell aggregates and debris. The proportions of cells in various cell cycle phases were assessed using Incyte 3.3. Software.

Cell fractionation assay

PC3 cells were seeded in 100 mm dishes at a density of 2 × 106 in three variants: (i) control – cells without addition of the nucleoside, (ii) cells treated with 20 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3, and (iii) cells treated with 100 µM dA-NHbenzylOCF3. The cells were incubated for 48 h, trypsinized, and centrifuged to obtain cell pellets. Fractionation was performed using the Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Abcam, UK). 200 µL of cytosol extraction buffer containing 2 µL of protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 µL DTT (1 M) was added to the collected cells, and samples were centrifuged at 500 x g for 3 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed. An additional 200 µL of cytosol extraction buffer was added, and the samples were resuspended using vertexing and incubated on ice for 10 min. Then, 11 µL of ice-cold lysis buffer was added to each sample, vortexed, and incubated on ice for 1 min. Subsequently, the cell samples were centrifuged for 5 min at maximal speed in a microcentrifuge (16,000 x g), and the supernatant fractions (cytoplasmic extract) were transferred to clean Eppendorf tubes and kept on ice. The remaining cell pellets were resuspended in 100 µL of ice-cold nuclear extraction buffer (containing 2 µL protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 µL DTT (1 M)). Samples were vortexed for 15 s and returned to ice. This step was repeated every 10 min for a total of 40 min. After this, the samples were centrifuged (16,000 x g for 10 min), and the supernatants were transferred to clean Eppendorf tubes (nuclear extract) and kept on ice.

DNA digestion

The PC3 cells were seeded in 100 mm dishes at a density of 2 × 106 in three variants: (i) control – cells without compound addition, (ii) cells treated with 20 µM of dA-NHbenzylOCF3, and (iii) cells treated with 100 µM of dA-NHbenzylOCF3. The cells were incubated for 48 h and then harvested on ice mechanically using a cell scraper. The collected cell pellets were subjected to purification and DNA isolation using the GeneMATRIX kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (EURx, Poland). A lysis buffer and RNase, which catalyzes RNA degradation, were added to the cell pellet containing the tested derivative. Subsequently, after the addition of proteinase K, the samples were incubated at 70 °C for 10 min in a thermocycler (Mastercycler Gradient). The lysate was then transferred to a tube with a specialized membrane, washed with appropriate washing solutions, and centrifuged. The final step involved the digestion of DNA into nucleosides. In this case, 10 µL of 10x concentrated reaction buffer containing 30 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0) and 1 mM zinc acetate were added to samples with DNA fragments to a final volume equal to 100 µL. Then, two enzymes − 1 µL (0.2 U) of Nuclease P1 and 1 µL (0.005 U) of Spleen were added, and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The second step collects the addition of 7.5 µL of 20x concentrated digestion buffer (1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris with a pH 8.9 and 40 µL DTPA), 40.5 µL water to final volume equals 150 µL and 1 µL of DNAse to each sample and incubated in 37 °C for 1 h. After this time, enzymes were added sequentially: 2 µL BAP, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C, and then 2 µL SVP, with another incubation under the same conditions for 1 h.

Nucleoside digestion

The Nucleoside Digestion Kit (New England Biolabs, US) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 5 µL of 10x nucleoside digestion mix buffer and 2.5 µL of nucleoside digestion mix were added to the cell samples. The solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, lyophilized, and analyzed by LC-MS.

Statistical analysis

Mean values were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. Data are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) derived from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Levels of statistical significance were denoted as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

References

Rak, J. et al. Mechanisms of damage to DNA labeled with electrophilic nucleobases induced by ionizing or UV radiation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119(26), 8227–8238. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b03948 (2015).

Makurat, S. et al. Guanosine dianions hydrated by one to four water molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13(14), 3230–3236. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c00512 (2022).

Lehnert, S. Biomolecular action of ionizing radiation. https://doi.org/10.1667/rrxx07.1 (2007).

von Sonntag, C. Free-Radical-Induced DNA damage and its repair. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-30592-0 (2006).

Daşu, A. & Denekamp, J. New insights into factors influencing the clinically relevant oxygen enhancement ratio. Radiother Oncol. 46(3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00185-0 (1998).

Oronsky, B. T., Knox, S. J. & Scicinski, J. Six degrees of separation: The oxygen effect in the development of radiosensitizers. Transl Oncol. 4(4), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1593/tlo.11166 (2011).

Djordevic, B. & Szybalski, W. Genetics of human cell lines. III. Incorporation of 5-bromo- and 5-iododeoxyuridine into the deoxyribonucleic acid of human cells and its effect on radiation sensitivity. J. Exp. Med. 112 (3), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.112.3.509 (1960).

Gudjonssona, O. et al. Analysis of 76Br-BrdU in DNA of brain tumors after a PET study does not support its use as a proliferation marker. Nucl. Med. Biol. 28 (1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-8051(00)00193-1 (2001).

Kriss, J. P., Maruyama, Y., Tung, L. A., Bond, S. B. & Révész, L. The fate of 5-bromodeoxyuridine, 5-bromodeoxycytidine, and 5-iododeoxvcvtidine in man. Cancer Res. 23, 260–268 (1963).

Phillips, T. L., Scott, C. B., Leibel, S. A., Rotman, M. & Weigensberg, I. J. Results of a randomized comparison of radiotherapy and bromodeoxyuridine with radiotherapy alone for brain metastases: Report of RTOG trial 89 – 05. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 33(2), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(95)00168-X (1995).

Chomicz-Mańka, L., Rak, J. & Storoniak, P. Electron-induced elimination of the bromide anion from brominated nucleobases. A computational study. J. Phys. Chem. B 116(19), 5612–5619. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp3008738 (2012).

Cecchini, S., Girouard, S., A Huels, M., Sanche, L. & J Hunting, D. Interstrand cross-links: A new type of γ-ray damage in bromodeoxyuridine-substituted DNA. Biochemistry 44(6), 1932–1940. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi048105s (2005).

Westphal, K. et al. Irreversible electron attachment – a key to DNA damage by solvated electrons in aqueous solution. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13(41), 10362–10369. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ob01542a (2015).

Makurat, S., Chomicz-Mańka, L. & Rak, J. Electrophilic 5-substituted uracils as potential radiosensitizers: Density functional theory study. ChemPhysChem 17(16), 2572–2578. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201600240 (2016).

Chomicz, L. et al. How to find out whether a 5-substituted uracil could be a potential DNA radiosensitizer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4(17), 2853–2857. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz401358w (2013).

Zdrowowicz, M. et al. DNA damage radiosensitizers geared towards hydrated electrons. Pract. Aspects Comput. Chem. V https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83244-5_4 (2022).

Wesolowski, S. S., Leininger, M. L., Pentchev, P. N. & Schaefer, H. F. Electron affinities of the DNA and RNA bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123(17), 4023–4028. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja003814o (2001).

Polska, K., Rak, J., Bass, A. D., Cloutier, P. & Sanche, L. Electron stimulated desorption of anions from native and brominated single stranded oligonucleotide trimers. J. Chem. Phys. 136(7), 075101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3685587 (2012).

Park, Y., Polska, K., Rak, J., Wagner, J. R. & Sanche, L. Fundamental mechanisms of DNA radiosensitization: Damage induced by low-energy electrons in brominated oligonucleotide trimers. J. Phys. Chem. B 116 (32), 9676–9682. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp304964r (2012).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98(7), 5648–5652. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464913 (1993).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. Gen. Phys. 38(6), 3098–3100. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098 (1988).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 37(2), 785–789. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 (1988).

Hehre, W. J., Ditchfield, K. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 56(5), 2257–2261. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1677527 (1972).

Ditchfield, R., Hehre, W. J. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. IX. An extended Gaussian-type basis for molecular-orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 54(2), 724–728. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1674902 (1971).

Makurat, S., Spisz, P., Kozak, W., Rak, J. & Zdrowowicz, M. 5-iodo-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine as a sensitizer of x-ray induced cancer cell killing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(6), 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061308 (2019).

Sosnowska, M., Makurat, S., Zdrowowicz, M. & Rak, J. 5-selenocyanatouracil: a potential hypoxic radiosensitizer. Electron attachment induced formation of selenium centered radical. J. Phys. Chem. B. 121(25), 6139–6147. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b03633 (2017).

Spisz, P. et al. Why does the type of halogen atom matter for the radiosensitizing properties of 5-halogen substituted 4-thio-2’-deoxyuridines? Molecules 24(15), 2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24152819 (2019).

Makurat, S. et al. 5-selenocyanato and 5-trifluoromethanesulfonyl derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine: Synthesis, radiation and computational chemistry as well as cytotoxicity. RSC Adv. 8(38), 21378–21388. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ra03172j (2018).

Spisz, P. et al. Uracil-5-yl o-sulfamate: An illusive radiosensitizer. Pitfalls in modeling the radiosensitizing derivatives of nucleobases. J. Phys. Chem. B 124(27), 5600–5613. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c03844 (2020).

Cossi, M., Barone, V., Cammi, R. & Tomasi, J. Ab initio study of solvated molecules: A new implementation of the polarizable continuum model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 255(4–6), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(96)00349-1 (1996).

Vivet Boudou, V. et al. 8-modified-2’-deoxyadenosine analogues induce delayed polymerization arrest during hiv-1 reverse transcription. PLoS One 6(11), e27456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027456 (2011).

Stockert, J. C., Horobin, R. W., Colombo, L. L. & Blázquez-Castro, A. Tetrazolium salts and formazan products in cell biology: viability assessment, fluorescence imaging, and labeling perspectives. Acta Histochem. 120(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2018.02.005 (2018).

Matsui, T. et al. Robustness of clonogenic assays as a biomarker for cancer cell radiosensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(17), 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174148 (2019).

van Leeuwen, C. M. et al. The Alfa and beta of tumours: a review of parameters of the linear-quadratic model, derived from clinical radiotherapy studies. Radiat. Oncol. 13(96). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-018-1040-z (2018).

Franken, N. A. P.et al cell survival and radiosensitisation: modulation of the linear and quadratic parameters of the LQ model (review). Int. J. Oncol. 42(15), 1501–1515. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1857 (2013).

Pauwels, B. et al. The radiosensitising effect of gemcitabine and the influence of the rescue agent amifostine in vitro. Eur. J. Cancer 39(6), 838–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049 (2003).

Taneja, N. et al. Histone H2AX phosphorylation as a predictor of radiosensitivity and target for radiotherapy. J. Biol. Chem. 279(3), 2273–2280. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M310030200 (2004).

Bernhard, E. J., Maity, A., Muschel, R. J. & McKenna, W. G. Effects of ionizing radiation on cell cycle progression—a review. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 34(2), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01275210 (1995).

Pawlik, T. M. & Keyomarsi, K. Role of cell cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 59(4), 928–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.005 (2004).

Fukui, K. The path of chemical reactions - the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 14(12), 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar00072a001 (1981).

Wong, M. W., Wiberg, K. B. & Frisch, M. Hartree-Fock second derivatives and electric field properties in a solvent reaction field: Theory and application. J. Chem. Phys. 95(12), 8991–8998. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.461230 (1991).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Rev. D.01. (Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Dennington, R., Keith, T. A. & Millam, J. M. GaussView 6. (Gaussian, 2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish National Science Center (NCN) under the Program Ceus-Unisono, Grant No. UMO-2020/02/Y/ST4/0011 (J. Rak) and Department of Chemistry University of Gdańsk under the Young Scientists Research Program, Grant No. 539-T080-B985-23 (M. Datta). Calculations have been carried out using a local computer cluster.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.R., M.D., and M.Z. Formal analysis: M.D. and J.R. Investigation: M.D., A.S., A.C., and S.D. Methodology: M.D., A.C., A.S., and S.D. Project administration: M.D. and J.R. Resources: J.R., M.D. Supervision: J.R. Original draft preparation: M.D., J.R., A.S., A.C., S.D., and M.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Datta, M., Szczyrba, A., Czaja, A. et al. Substituted benzylamino-2′-deoxyadenosine a modified nucleoside with radiosensitizing properties. Sci Rep 15, 17535 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99262-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99262-8