Abstract

In this study, we examined the major sources of particulate organic matter (POM) in the Godavari River during high flow and low flow periods, to understand the impact of excess nitrogen (N)-fertilizers used in agricultural fields. δ13C of particulate organic carbon (POC) and δ15N of particulate nitrogen (PN), elemental carbon (C) to N ratio and POC:Chl-a ratios indicated that in-situ sources predominantly contributed (~ 60%) during low flow period, whereas, terrestrial sources largely contributed during high flow period (75–80%). This is attributed to prevailing conducive conditions such as low flow, better light availability due to low suspended matter and availability of nutrients for phytoplankton growth during former period, whereas increased transport of particulate and dissolved materials from land to river during the latter period. δ15NPN during low flow (7.4 ± 2.9‰) and high flow (9.4 ± 2.1‰) periods demonstrate that contribution of POM produced from N-fertilizers (δ15NPN: 0 ± 1‰) is not significant, rather than hitherto hypothesized. It could be due to seepage of excess N-fertilizers used in agricultural fields into groundwaters rather than transporting to rivers and/or transformation to another from through nitrification/denitrification processes within soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rivers are the major means of transport of dissolved and particulate material from land to sea via estuaries1,2. Rivers carry significant amounts of particulate organic matter (~150 to 200 Tg yr-1)2,3,4 and suspended sediments5 along with dissolved inorganic nutrients6,7, dissolved organic matter8,9 and various types of pollutants10,11 to the global ocean. Riverine export of land-driven nutrients in large quantities, mainly due to anthropogenic activities, such as the use of excess synthetic fertilizers in agricultural and aquacultural practices, domestic and industrial sewage, often causes ‘eutrophication’, in estuaries and coastal waters12,13. Formation of eutrophication ultimately leads to the development of ‘dead zones’ in coastal waters. Maure et al.14 reported that about 1.15 million km2 area of global coastal waters (depth: <200m) are eutrophic potential.

India is the second largest consumer of synthetic fertilizers in the world, with an annual consumption of 26.5 Tg, after China (48.8 Tg), with a global share of 15.3% in N-fertilizer consumption15. The most commonly used N, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizers in agriculture practices in India for restoration of soil nutrients and increasing the crop yield are Urea (46% N), Diammonium phosphate (DAP; 46% P and 18% N), Muriate of Potash (60% K) and other complex (NPK) fertilizers in different ratios such as 10:26:26, 19:19:19 and 12:32:16 etc. Excess fertilizers used in agriculture and aquaculture activities are expected to reach rivers, estuaries and coastal oceans. Impact of these fertilizer nutrients on ecosystem in Indian rivers, estuaries and coastal waters remain poorly understood. Occurrence of oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) due to seasonal upwelling along west coast of India is reported to be intensified, and leads to eutrophication due to transport of fertilizer nutrients to coastal ocean16. Expansion of OMZ (both horizontally and vertically) in the Arabian Sea was attributed to increased organic matter loading to deeper depths. This increase of organic matter could be due to either wind-driven coastal upwelling or supply of anthropogenic nutrients from coastal cities along west coast of India17. Bristow et al.18 reported that OMZ in the Bay of Bengal is at its tipping point, and it will become dead zone if primary production in the overlying water column increases by transport of anthropogenic nutrients and/or intensification of summer monsoon. Although many studies attributed various biogeochemical processes in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal to anthropogenic nutrients (agricultural, industrial and domestic sewage) from the Indian subcontinent, quantitative studies on anthropogenic nutrients budget and identification of nutrient sources are very limited. Krishna et al.7 reported that Indian monsoonal rivers annually export only 0.22 ± 0.05 Tg (1Tg = 1012 g) of dissolved inorganic nitrogenous nutrients to the northern Indian Ocean, and such a low fluxes were attributed to efficient (~ 91%) elimination/retention of nutrients before reaching the coastal ocean.

In this study, we investigated the major sources of particulate organic carbon (POC) and particulate nitrogen (PN) in the Godavari river from the place of its origin (Nasik) to the place at which it confluences with the Bay of Bengal (Yanam), covering a stretch of ~1600 km, during both low flow and high flow periods. The Godavari is the largest monsoonal river that exports highest amount of POC (2.81*106 tons yr-1), PN (0.29*106 tons yr-1), DOC (0.45*106 tons yr-1), DON (0.085*106 tons yr-1) and suspended load (~170x106 tons)8,19,20 among the monsoonal rivers in India. It accounts for ~1.7% of the total POC export by major rivers in the world3.

Elemental ratios of carbon to nitrogen (C:N ratio), POC:Chl-a ratios and stable isotopic signatures of POC (δ13CPOC) and PN (δ15NPN) are well established tracers to delineate the major sources of organic matter in rivers21,23,24,25, estuaries26, coastal27 and open ocean regions28,29. However, a caution is required while using these tracers for identification of POM sources because decomposition of POM by heterotrophic organisms modifies isotopic signatures in the residual POM30,31,32. The δ13CPOC values indicate source of inorganic carbon used for production of POC, and therefore have distinctly different δ13CPOC values for freshwater phytoplankton (-33.2‰ to -27.5‰)33 and terrestrial POC (-28‰ to -26‰)32. Similarly, δ15NPN depends on δ15N of nitrogenous nutrients used for production of PN. However, various internal processes such as nitrification, denitrification, N2 fixation influence δ15NPN values due to preferential uptake of lighter isotope (14N) over heavier isotope (15N) in these processes34,35. Nutrients derived from diverse sources have distinctly different δ15N values. For instance, PN produced from sewage nutrients has relatively enriched δ15N (~14±4‰)36 compared to PN supported by synthetic N-fertilizers (0±1‰)37,38,39 and N2 fixation (-2‰ to 1‰)40,41. The δ15NPN values are thus indicate nutrient sources used for primary production. The main objectives of our study are (i) to investigate the major sources of POC and PN, and their seasonal variability and (ii) to understand the impact of synthetic N-fertilizers on POC and PN in the Godavari River.

Study region and sample collection

Study region

Godavari River is the 3rd largest river (after Ganges and Brahmaputra) in India that originates in the Western Ghats at Triambak near Nasik City at an altitude of ca. 1600 m. It flows eastward for about 1600 km across the Indian peninsula before it drains into the Bay of Bengal. The Godavari River discharges ~ 110 km3 yr-1 of fresh water and 170 million tons yr-1 of suspended sediment to the Bay of Bengal3,20. The Godavari River basin extends from 73o26’E to 83o07’E and from 16o16’N to 22o36’ N (Fig. 1), with an area of ~ 3.1 × 105 km2 19. The river drains mainly Deccan Trap basalts and metamorphic rocks (Pre-Cambrian) in upper and lower reaches of the river, respectively. Due to strong seasonal variability in rainfall pattern over the catchment, with > 80% of the annual rainfall during SW monsoon, the high flow of water in the river confine only to SW monsoon season (Fig. 2). Lower basin of the river receives intense rainfall (1600 to > 3200 mm yr-1) than upper basin (< 800 to 1200 mm yr-1) within SW monsoon period42. Semi-arid and monsoonal climate prevails over the basin. Maximum and minimum temperatures are higher in lower basin than in upper basin43. Dominance of vegetation in the Godavari basin changes from grassland/cropland in upper basin to forest and shrub in lower basin of the river. Along the entire stretch, about 25 tributaries join the Godavari River and create an extensive delta on east coast of India44. A total of 921 dams of different sizes were constructed so far on the Godavari River and its tributaries mostly for irrigation purposes, and only a few for hydro-electric power generation (water resources information system of India, http://india-wris.nrsc.gov.in). Population density in the basin ranges from as low as 25–50 persons km-2 to 500–1000 persons km-2, with a mean value of 194 persons km-2.45.

(a)Map showing Godavari River from its origin at Nasik to its mouth at Yanam. Sampling locations during high flow and low flow periods were shown by filled circles of red and grey colour, respectively. India map with Godavari River is shown in inset. Station at which freshwater phytoplankton collected is shown by cyan colour star. Major tributaries, Wardha, Pranahita and Indravati in the lower reaches of the river are also shown. (b) Land use and land cover map of the Godavari River basin. Sampling stations along the course of the river are marked by filled (blue colour) circles. Major tributaries, Wardha, Pranahita and Indravati, in lower reaches of the river are also shown.

Sample collection

Surface water samples were collected using 5L Niskin samplers at 39 locations along entire stretch (~ 1600 km) of the Godavari River from its headland waters to mouth (Fig. 1a) during low flow (non-monsoon) period (November–December 2011). However, samples were collected only at 18 locations along entire stretch of the river during high flow (southwest monsoon) period (Fig. 1a) because many of the locations were not accessible for sample collection during this period. Land use and land cover map of the Godavari River is shown in Fig. 1b. Surface water samples were collected for dissolved inorganic nutrients, dissolved oxygen (DO), chlorophyll-a (Chl-a), total suspended matter (TSM), POC and PN. Surface water samples were collected in middle of the river-channel using mechanized boats to minimize contamination from river banks. Samples for freshwater phytoplankton were collected in the lower reaches of the river (Fig. 1a). Different parts (leaf, part of stem and part of root) of the abundant C3 plants (rice, cotton, turmeric and wheat) and C4 plants (sugarcane, maize, bajra and sorghum) and surface soils (0-10 cm) were collected in drainage basin of the river. Location details, δ13C and δ15N values of soils, C3 and C4 plants collected in drainage basin of the river were given elsewhere46. Rainfall and temperature data in the Godavari basin was taken from Central Water Commission, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India43. Study region was divided into two parts for discussion based on geological characteristics and spatial variability in rainfall intensity and environmental conditions of the river basin. Upper reaches of the river extend up to ~ 1100 km from origin of the river, and lower reaches extend from ~ 1100 km to mouth of the river.

Methodology

About 500 ml of water sample was filtered through a non-combusted GF/F filter (nominal pore size: 0.7 µm; Whatman) under vacuum, and the material retained on filter was extracted into N,N, dimethyl formamide (DMF). Concentration of Chl-a in the extract was measured using spectrofluorophotometer (Carry Eclipse, Varian, USA) following Suzuki and Ishimaru47. Analytical precision for the method, expressed as standard deviation, was ± 4%. DO was determined by Winkler’s titration method of Carritt and Carpenter48 using potentiometric end point detection (Metrohm, Switzerland) at a temporary field laboratory on the same day of collection. Analytical precision, in terms of standard deviation, was ± 0.07%. Total suspended matter (TSM) was determined by the weight of material retained on filter (0.22 µm, polycarbonate) after filtering 300–500 ml of water sample followed by drying in an oven (50 °C, 48 h). Dissolved inorganic nutrients were analysed by the standard colorimetric method following Grashoff et al.49 using an auto analyzer (SAN++, Skalar, The Netherlands). Based on repeated analysis of standards and samples, precision of the method was found to be ± 0.02, 0.02, 0.01 and 0.02 µM for ammonium, nitrite + nitrate, phosphate and silicate, respectively.

Content and isotopes of POC and PN

For POC analysis, water sample (~ 500 ml) was passed through a pre-combusted (300 °C; 6 h) GF/F filter (nominal pore size: 0.7 µM; diameter: 47 mm; Whatman) under vacuum at a field laboratory, and preserved in ice for further processing at shore laboratory. After drying at 60 °C (24 h) in an oven at institute’s laboratory, part of the filter was used directly for determination of concentration and isotopic composition of PN using an elemental analyzer (Flash EA, Thermo) coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS, Delta V Plus, Thermo Electron, Germany) via Conflo IV. Part of the filters was acid fumigated to remove traces of inorganic carbon, and analyzed for concentrations and stable isotope ratios of POC using EA-IRMS instrument. The international atomic energy agency (IAEA) standards and laboratory standards such as glutamic acid, alanine, organic analytical standard (OAS) were used for calibration. Long term precision of the instrument was ± 0.2‰ for both C and N isotopes. Concentrations of POC and PON were reported in mg L-1 while their stable isotope ratios were expressed in per mil deviation from VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Beleminte) for carbon, and atmospheric air for nitrogen as given below.

where, Xsamp stands for 13C/12C and 15N/14N of a sample for carbon and nitrogen, respectively. The Xstd represents 13C/12C and 15N/14N of standard, i. e., VPDB and atmospheric air, respectively. Measurement of δ13C, δ15N and C:N ratios of freshwater phytoplankton (group level) was described elsewhere46. Software program “Grapher” (version 5) was used for graphical representation of data. Two tailed homoscedastic t-test was used to examine statistical significance of difference for various parameters between upper and lower reaches of the river.

Quantification of proportional contributions from major sources

Bayesian isotope mixing model SIAR (Stable Isotope Analysis in R) was used to estimate proportional contributions of OM from major sources to POM in the Godavari River. SIAR is an open source R package and available at Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) site (http://cran.r-project.org). SIAR model uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for simulating the probable values for fitting algorithms50,51. The model includes covariance structure that defines the ability of model to separate various sources through the diagnostic matrix plot. Actual correlation coefficient of posterior distributions in the matrix plot describes the closeness of different sources. Lower correlation coefficient denotes well isolation of contributions from different sources, while the negative correlation indicates end-member values of possible sources are close to each other or overlapping51. Inclusion of the residual error term is an additional advantage of this model compared to the other Bayesian mixing models51. The model has already been used for quantification of proportional contributions of OM from major sources to POM in estuaries46,52 and coastal systems53,54. Since ‘SIAR’ is a dual isotope mixing model that uses both δ13C and δ15N, it gives a better quantification of source apportionment of OM than single isotope based models. Selection of end member values is crucial for isotope mixing models because output of the model mainly depends on δ13C and δ15N values of end members.

Measured δ13C and δ15N values of microscopically separated freshwater phytoplankton groups collected from lower reaches of the river (-31.2 ± 0.6‰ and 6.2 ± 0.5‰, respectively) were used as freshwater phytoplankton end member values. Mean δ13C and δ15N values of abundant terrestrial C3 plants (rice, cotton, turmeric and wheat) (-25.9 ± 1.2‰ and 5.1 ± 2.1‰, respectively) and C4 plants (sugarcane, maize, bajra and sorghum) (-13.1 ± 1.2‰ and 4.4 ± 2.1‰, respectively), and surface soils (-19.1 ± 2.4 and 10.1 ± 2.7‰, respectively) in the Godavari basin46 were used as end members for terrestrial C3 and C4 plants and soil derived OM, respectively. δ15N of sewage is typically enriched, and ranges between 12‰ to 25‰55,56. Mean δ13C and δ15N values of the sewage collected from Bombay (-31.5 ± 1.0‰ and 15.8 ± 1.6‰, respectively)57, the major city near upper reaches of the river were used as sewage end member values. Similar δ15N values are also reported for sewage from Visakhapatnam City near the lower reaches of the river (~ 14 ± 4‰)36.

Results

Seasonal variability (low flow and high flow periods)

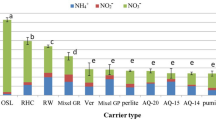

Dissolved inorganic nutrients such as ammonium, nitrite + nitrate and silicate concentrations were higher during high flow period (3.7 ± 5.1, 53.2 ± 20.9 and 49.7 ± 14.5 µM, respectively) compared to low flow period (0.4 ± 0.2, 15.5 ± 18.6, and 40.6 ± 11.7 µM, respectively) (Figs. 3a&b). However, phosphate concentrations were nearly equal (p = 0.72) during low flow (12.0 ± 7.6 µM) and high flow (12.3 ± 8.2 µM) periods (Figs. 3a&b; Table 1). Chl-a distribution was relatively less heterogeneous during low flow period (mean 11 ± 6 mg m-3) compared to high flow period (20 ± 19 mg m-3, Table 1). TSM concentrations varied between 2.0 and 38.6 mg L-1 (except higher concentration of 72 mg L-1) during low flow period, whereas it varied widely between 1 and 186 mg L-1 during high flow period (Table 1). Percent of organic carbon in TSM (%OC) was higher (p = 0.04) during low flow period (mean 11.5 ± 8.4%, range: 0.9–35.7%) compared to high flow period (6.3 ± 6.3% and 0.5–20.3%, respectively) (Figs. 4a&b).

Mean concentrations of dissolved inorganic nutrients such as nitrite+nitrate (NO2-+NO3-, µM), phosphate (µM), silicate (µM) and ammonium (µM) in upper and lower reaches of the Godavari River during (a) low flow period and (b) high flow period. Concentrations of ammonium were shown on right side y-axis while the other nutrients were shown on left side y-axis.

Mean concentrations of Chlorophyll-a (Chl-a, mg m-3), particulate organic carbon (POC, mg L-1), particulate nitrogen (PN, mg L-1) and total suspended mater (TSM, mg L-1) in upper and lower reaches of the Godavari River during (a) low flow period and (b) high flow period. Concentrations of POC and PON were shown on the right side y-axis and the remaining parameters were shown on the left side y-axis.

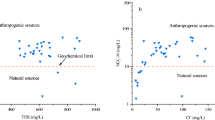

POC concentrations ranged from 0.4—2.1 mg L-1 and 0.2 – 1.8 mg L-1 during low flow and high flow periods, respectively (Table 1). Concentrations of POC found in this study are similar with those reported earlier in the Godavari River19,22. Relatively higher range of PN concentrations were found during low flow period (0.05 – 0.35 mg L-1) compared to high flow period (0.01 – 0.11 mg L-1). Elemental C:N ratios ranged from 3 to 22 and 10 to 29 during low flow and high flow periods, respectively (Table 1), with lower mean ratios during former than latter period (Figs. 5a&b) (t-test; p < 0.001). POC:Chl-a ratio, an indicator of contribution from phytoplankton biomass to total POC, varied from 32 to 275 during low flow period, whereas it varied widely between 13 and 677 during high flow period (Table 1). The δ13CPOC varied from -32.8‰ to -20.7‰ and from -30.9‰ to -22.8‰ during low flow and high flow periods, respectively (Table 1). Relatively depleted mean δ13CPOC values were observed during low flow (-28.9 ± 2.6‰) compared to high flow period (-25.8 ± 2.6‰) (t-test; p < 0.001). The δ13CPOC values observed in this study during low flow (mean -28.9 ± 2.6‰) and high flow (-25.8 ± 2.6‰) periods are similar to those reported earlier in the Godavari River58 and elsewhere in the world, for example, Danube (-32.3 to -24.76‰)59, Congo (-27.8 to -26.3‰)60, Mekong (-29‰)61 and Orinoco (-29.5 to -24.4‰)62. δ15NPN values broadly varied from 4.8‰ to 15.0‰ and from 5.7‰ to 13.1‰ during low flow and high flow periods, respectively, except three stations near origin of the river where depleted δ15NPN (1.2—2.9‰) were observed during low flow period.

Mean values of POC:Chl-a and molar C:N ratios, stable carbon isotopes of POC (δ13CPOC, ‰) and stable nitrogen isotopes of PN (δ15NPN, ‰) in upper and lower reaches of the Godavari River during (a) dry period and (b) wet period. The δ13CPOC values were shown on the right side y-axis and the remaining parameters were shown on the left side y-axis.

Spatial variability (upper and lower reaches of the river)

Both nitrite + nitrate and phosphate concentrations were higher in upper than lower reaches of the river during low flow period (Figs. 3a&b), however, this variation is not statistically significant (p = 0.22 and p = 0.18, respectively). During both low flow and high flow periods, upper reaches of the river recorded relatively high mean Chl-a (27.5 and 12.2 mg m-3, respectively) compared to lower reaches of the river (6.8 and 6.3 mg m-3, respectively) (t-test, p < 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4a&b). Higher mean TSM concentrations were found in upper (14.4 ± 15.5 mg L-1) than lower reaches of the river (5.1 ± 2.1 mg L-1) during low flow period, but the difference is not statistically significant. Contrastingly, lower TSM concentrations were observed in upper (21 ± 20 mg L-1) than lower reaches of the river (133 ± 53 mg L-1) (t-test; p < 0.001) during high flow period (Fig. 4a&b). Percent organic carbon in TSM (%OC) was low in upper (10 ± 8%) compared to lower reaches (17 ± 5%) of the river during low flow period (p = 0.05), whereas an opposite pattern was found during high flow period, with higher values in upper (9.6 ± 5.9%) compared to lower reaches of the river (0.9 ± 0.3%) (p = 0.002) (Figs. 4a&b). Mean POC concentrations were similar in upper and lower reaches of the river during low flow period (Fig. 4a). Whereas, lower reaches of the river recorded high POC concentrations compared to upper reaches during high flow period (Fig. 4b), however, it is not statistically significant (t-test; p = 0.12). Upper and lower reaches of the river recorded similar PN concentrations during both low and high flow periods (Figs. 4a&b).

Mean C:N ratios were similar in upper and lower reaches of the river during both low flow and high flow periods (p = 0.54 and p = 0.82, respectively) (Fig. 5a&b). Mean POC:Chl-a ratios were marginally lower in upper (98 ± 67) compared to lower reaches of the river (146 ± 36) during low flow period (Fig. 5a), however, it is significantly lower during high flow period (53 ± 64 and 318 ± 300, respectively) as shown in Fig. 5b (t-test, p < 0.05). Mean δ13CPOC values were similar in upper (-28.6‰) and lower reaches (-29.9‰) of the river during low flow period (Fig. 5a). Whereas, depleted δ13CPOC values were found in upper (-26.8‰) compared to lower reaches of the river (-23.8‰) during high flow period (Fig. 5b). δ15NPN showed relatively less spatial variability during low period, however, relatively enriched δ15NPN were found in lower reaches (10.5 ± 2.0‰) than upper reaches (8.7 ± 1.8‰) of the river during high flow period (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

Seasonal variations in the sources of POC and PN

Surface runoff during southwest (SW) monsoon transports land borne nutrients (from soils) to rivers. Drainage basin of the Godavari River receives > 80% of its annual rainfall only during four months period of SW monsoon (June–September)19. Intense rainfall during this period leaches nutrients, POC, PN and other dissolved materials from soils, leaf litter, debris of land plants and agricultural crops, excess fertilizers used in agricultural fields and sewage etc., and transports to rivers. Intense rainfall also enhances soil erosion in the drainage basin, leading to enhanced transport of particulate material to rivers63. Relatively higher TSM concentrations during high flow period (59 ± 65 mg L-1) compared to low flow period (12.4 ± 14.2 mg L-1) in this study indicate that significant input of terrestrial material to rivers during former period. However, such a difference was not noticed in POC concentrations which showed similar concentrations during high flow (0.8 ± 0.3 mg L-1) and low flow (0.9 ± 0.5 mg L-1) periods. This is attributed to significant amount of POC contribution from in-situ sources during low flow period because of prevailing conducive conditions for phytoplankton growth such as better light availability (low TSM; 12.4 ± 14.2 mg/L; Table 1) and stable water column (low flow) during this period. Lower TSM concentrations allow light penetration to deeper depths in the water column and thus enhance the light availability to phytoplankton leading to high primary production. Relatively high PN concentration during low flow (mean: 0.11 mg L-1) than high flow period (0.06 mg L-1) also suggest that major contribution of POM is from N-rich in-situ sources during former period, and N-poor terrestrial sources during latter period. This is because POM derived from in-situ sources predominantly contain N-rich proteins than N-poor cellulose, whereas, terrestrial POM mainly derived from vascular plants largely contain N-poor cellulose than N-rich proteins64,65.

Mean C:N ratios found during low flow period (9 ± 4) are close to the range of C:N ratios of POM produced by phytoplankton (6–10)26,66, (6.7)67, (6–8)68,69 indicating that predominant contribution of POM is possible from freshwater phytoplankton. On the other hand, C:N ratios during high flow period (18 ± 4) are close to typical C:N ratios of terrestrial POM (> 12)2,32,70 and measured C:N ratios of soils in the Godavari basin (19 ± 4), but lower than measured C:N ratios of dominant C3 plants (41 ± 32) and C4 plants (53 ± 41) in drainage basin of the Godavari river. These results indicate that soil OM may be one of the major sources of POM in the river during high flow period. Although soils contain debris of C3 and C4 plant material, the lower C:N ratios of soils than C3 and C4 plants are due to bacterial colonization32, and humification and mineralization processes71 during decomposition of terrestrial POM in soils that result in C:N ratios of soils in the range of 8–2072. The POC:Chl-a ratios of < 200 and > 200 were used to characterize POC of phytoplankton and terrestrial origin, respectively73,74. Broad range of POC:Chl-a ratios during low flow period (32–275, mean 106 ± 65) and high flow period (13–677, 155 ± 225) likely indicate that both freshwater phytoplankton and terrestrial sources contribute to POM, with a predominance of the former during low flow period and the latter during high flow period.

The range of δ13CPOC observed during low flow period (-32.8 to -20.7‰) is close to δ13C of phytoplankton in the Godavari River (-31.2 ± 0.6‰), typical range of freshwater phytoplankton (-33.2 to -27.5‰)33, sewage (-31.5 ± 1.0‰)57 and terrestrial POM (-28 to -26‰)32,75, and measured δ13C of C3 plants (-27.4 to -24‰) and soils (-23.5 to -15.3‰) in the Godavari basin (Fig. 6). These results suggest that both in-situ and terrestrial sources, including sewage, likely contribute to POM during low flow period, with a predominance of the former than the latter. On the other hand, δ13CPOC values during high flow period (-30.0 to -22.8‰) are close to δ13C of typical terrestrial POM and measured terrestrial C3 plants of the Godavari basin, and slightly different from that of δ13C of freshwater phytoplankton and sewage (Fig. 6), suggesting that POM is contributed by both terrestrial and in-situ sources, with a predominance of the former than the latter.

Isospace plot of the δ13CPOC and δ15NPN in suspended particulate matter of the Godavari River during low flow period (hollow circles) and high flow period (hollow triangle). End member ranges of both δ13CPOC and δ15NPN of possible major sources of organic matter such as terrestrial C3 plants (TC3, black coloured lines) and C4 plants (TC4, red), soils (green), freshwater phytoplankton (blue) and sewage (cyan coloured lines) to suspended particulate organic matter (POM) in the Godavari River were also shown.

Broad range of δ15NPN during low flow period (4.8 to 15.0‰; mean 7.8 ± 2.6‰) indicates that predominant contribution of POM is from phytoplankton (5 to 8‰), with minor contribution from terrestrial sources, such as C3 plants (5.1 ± 2.1‰), C4 plants (4.4 ± 2.1‰) and soils (10.1 ± 2.7‰) (Fig. 6), corroborating with δ13CPOC results. However, mean δ15NPN values during high flow period (9.4 ± 2.1‰; range: 5.7—13.1‰,) are very close to δ15N of soils (10.1 ± 2.7‰) in the drainage basin, and significantly enriched than δ15N of C3 plants (5.2 ± 2.1‰) and C4 plants (4.4 ± 2.1‰) plants. These results likely indicate that terrestrial sources, mainly soil derived POM, contribute to POM with minor contribution from in-situ sources during high flow period. Contrary to this, Chl-a concentrations were lower during low flow (11 ± 6 mg m-3) than high flow period (21 ± 19 mg m-3). This discrepancy mainly arises from the large spatial variability in Chl-a and TSM concentrations between upper and lower reaches of the river within the high flow period. Upper reaches of the river showed higher Chl-a (27.5 ± mg m-3) and lower TSM (21 ± 20 mg L-1) than the lower reaches of the river (6.8 ± mg m-3 and 133 ± 53 mg L-1, respectively). Due to the joining of large tributaries, such as Wardha, Pranahita and Indravati in the middle course of the river (Fig. 1), the flow is strong and waters are turbid (TSM: 133 ± 53 mg L-1) leading to low Chl-a in the lower reaches of the river within the high flow period. No significant relationship of POC with either TSM or Chl-a confirm that both terrestrial and in-situ sources are contributing to POM1,25.

SIAR model results showed that freshwater phytoplankton contributes up to 60% during low period while contribution from terrestrial sources is predominant (~ 75–80%) during high flow period (Fig. 7). Prevailing conducive conditions, such as nutrient availability, stable water column (low flow) and better light availability (low TSM) to phytoplankton are attributed for major contribution from phytoplankton during low flow period. Consistent with our observation, predominance of phytoplankton derived POM during low flow periods was also reported in the Godavari River19,22 and some of the major rivers in the world, for example, Mississippi, Colorado, Rio Grande and Columbia21, Oubangui24, Umpqua76, Alsea77, Danube78, Garonne, Loire and Rhone79. On the other hand, predominant (~ 75–80%) contribution of POM from terrestrial sources, mainly sewage (~ 25–30%), soils (~ 20%), C3 plants (~ 20%) and C4 plants (~ 10%), during high flow period is attributed to export of POM from soils, debris of C3 and C4 plants and sewage in drainage basin to the river by intense runoff during this period80. Also, less contribution from phytoplankton (20–25%) due to high TSM (67 ± 66 mg L-1) that limits light availability to phytoplankton.

Spatial variations in the sources of POC and PN

Both POC and PN concentrations were similar in upper and lower reaches of the river during low flow period (Fig. 5a). However, significant spatial variability was observed during high flow period. During this period, relatively higher POC concentrations (1.2 mg L-1) associated with higher TSM (133 ± 53 mg L-1) and lower Chl-a (6.8 ± mg m-3) were found in the lower reaches of the river. On the other hand, relatively lower POC (0.8 mg L-1) associated with lower TSM (21 ± 20 mg L-1) and higher Chl-a (27.5 ± mg m-3) were observed in the upper reaches of the river. Intense rainfall (1600 to > 3200 mm yr-1)42, dominance of sandy clay loam soils81 and higher soil OC in northern part of the basin which drains into lower reaches of the river through the major tributaries, Wardha, Pranahita and Indtravati are attributed for the observed high POC and TSM concentrations in lower reaches of the river. Sandy clay loam soils are more susceptible to erosion by intense rainfall during SW monsoon due to higher soil detachment capacity82 and restrict infiltration of water83. In addition, high temperatures45, anthropogenic activities such as deforestation and increased agricultural activities in lower basin84 also support erosion of soils. Balakrishna and Probst22 reported high concentrations of TSM in tributaries of the Godavari River in lower basin, Wardha (129 mg L-1), Pranahita (113 mg L-1) and Indravati (79 mg L-1) than tributaries in upper basin of the river during high flow period. Although, upper basin is dominated by black soils and grasslands, lower TSM concentrations in upper reaches of the river could be due to less intensity of rainfall (< 800 to1600 mm yr-1) than lower basin of the river (1600 to > 3200 mm yr-1)42. Higher TSM concentrations (133 ± 53 mg L-1) significantly decreases the light penetration depth in the water column and thus restricts the light availability to phytoplankton leading to low primary production in lower reaches (Chl-a: 6.8 mg m-3). On the other hand, lower TSM concentrations (21 ± 20 mg L-1) in the upper reaches of the river allows light penetration to deeper depths and thus enhances the light availability to phytoplankton leading to high primary production (Chl-a: 27.5 mg m-3). These results demonstrate that in-situ sources predominantly contribute to POM pool in upper reaches while terrestrial sources in lower reaches of the river during high flow period. It is also evidenced from significantly high %OC in TSM in upper (9.6 ± 5.9%) than lower reaches of the river (0.9 ± 0.3%). However, based on δ13C (-24.5 ± 0.3‰) and low yield of lignin phenols (Λ8), Pradhan et al.58 concluded that algal POM is predominant in lower reaches of the river during high flow period. Even though, lignin phenols (Λ8) are specific markers for terrestrial sources of POM, they cannot differentiate contribution from lignin free algal POM and lignin degraded soil OM. Hence, lower yield of lignin phenols (Λ8) in lower reaches of the Godavari River during high flow period58 could be due to significant contribution from soil OM. SIAR model estimated that contribution from soil OM is ~ 30% and it is higher than freshwater phytoplankton contribution (~ 10%). Spatial variability in sources of POM in the Godavari River is therefore intimately linked to the intensity of soil erosion that is controlled by strong rainfall in the lower reaches (1600 to > 3200 mm yr-1) than the upper reaches (< 800 to1600 mm yr-1) of the river.

Impact of excess fertilizers use in agricultural activities

The δ15NPN signatures have not shown any evidence for significant contribution of POM produced from synthetic N-fertilizers in the Godavari River. The δ15N of synthetic fertilizer nitrogen was reported to be depleted (~ 0 ± 1‰)37,39,85 because they are manufactured from atmospheric N2. The δ15N of N-fertilizers such as KNO3, NH4NO3, Urea, (NH4)2SO4 and NPK (20:10:10) etc., manufactured by different companies were found to be in the range of -5.9 to 2.6‰, with a mean δ15N of -0.2‰85. Even though, India consumes 26.5 Tg yr-1 of synthetic fertilizers, and it accounts for 15.3% of the global N-fertilizer consumption15, δ15NPN values of this study (< 4.8‰) are enriched compared to typical δ15N of POM derived from fertilizer nitrogen (0 ± 1‰). These results demonstrate that impact of synthetic N-fertilizer usage in agricultural fields in drainage basin may be minor on ecosystem in the Godavari River. It could be due to retention and/or elimination of fertilizer nutrients due to their low utilization efficiency; only ~ 30 to 35% of the fertiliser nutrients applied is taken up by plant86,87. For instance, most commonly used nitrogen fertilizer, Urea, have the utilization efficiency of ~ 50% and the remaining 50% lost in different pathways; 2–20% through volatization, 15–25% reacting with organic compound in soils and 2–10% leaching into water88. Central Ground Water Board of India89 reported that concentrations of nitrate in ground waters of many Indian states are higher than 45 mg L-1, and attributed it to seepage of excess N-fertilizer used in agricultural activities into ground waters21,90,91. Rahman et al.91 reported elevated NO3- concentrations in ground waters of Rajasthan state, India and attributed to anthropogenic sources. Based on land use map and NO3- concentrations in ground waters (1 to 415 mg L-1) of Tamilnadu state, India, Jayarajan and Kuriachan92 confirmed that use of excess fertilizers and sewage are the major sources of elevated NO3- concentrations in ground waters. Several other studies also reported elevated NO3- concentrations in ground waters of different river basins and attributed to N-fertilizer usage93,94. Based on multiple stable and radioactive isotopes tracers, recently, Harris et al.95 demonstrated that ground water NO3- is originated from fertilizers in the western and eastern banks of the Nogoa River, Queensland, Australia. Recently, Kiran et al.96 reported concentrations and δ15N of nitrate (δ15NNO3-) along the bank of the Godavari estuary during high and low flow periods, and found similar values of δ15NNO3- during both the periods and attributed to the homogenization through mineralization/immobilization of NO3- in the ground water. The authors96 concluded that submarine groundwater discharge of denitrified NO3- is one of the major pathways of NO3- to the Godavari estuary. The δ15NPN values found in our study demonstrate that impact of N-fertilizer on POM in the Godavari River is not significant, rather than hitherto hypothesized. Further studies on δ15N of NO3- in the ground waters of the drainage basin are required to confirm the impact of N-fertilizers on ground waters N-nutrients in the Godavari drainage basin.

Conclusions

Major sources of POM, and their spatial and seasonal variations were investigated in the Godavari River using isotopic signatures of carbon and nitrogen in suspended particulate matter. Elemental C:N and POC:Chl-a ratios, and δ13CPOC and δ15NPN of suspended particulate matter clearly indicated that POM is predominantly contributed by water column phytoplankton (~ 60%) and terrestrial sources (75–80%) during low flow and high flow periods, respectively. Predominant contribution from phytoplankton is attributed to prevailing conducive conditions for phytoplankton growth during low flow period. On the other hand, major contribution from terrestrial sources is attributed to export of soils, debris of land plants, agricultural crops and sewage from drainage basin by the intense runoff during high flow period. Spatial variations in rainfall intensity, soil characteristics, land use change and agricultural activities in drainage basin of the river govern spatial variability in major POM sources. Relatively enriched δ15NPN ratios suggest that impact of N-fertilizers usage in agricultural fields of drainage basin is not significant on POM in the Godavari River. It is attributed to seepage of excess N-fertilizers into ground waters rather than their transportation to rivers.

Data availability

The data used in this study is available with the corresponding author (M.S. Krishna) and will be provided on reasonable request by e-mail (moturi@nio.org).

References

Meybeck, M. Riverine transport of atmospheric carbon: Sources, global typology and budget. Water Air Soil Poll. 70, 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01105015 (1993).

Hedges, J. I., Keil, R. G. & Benner, R. What happens to terrestrial organic matter in the ocean?. Org. Geochem. 27, 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00066-1 (1997).

Ludwig, W., Probst, J. L. & Kempe, S. Predicting the oceanic input of organic carbon by continental erosion. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy. 10, 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1029/95GB02925 (1996).

Schlünz, B. & Schneider, R. R. Transport of terrestrial organic carbon to the oceans by rivers: re-estimating flux- and burial rates. Int. J. Earth Sci. 88, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005310050290 (2000).

Beusen, A. H. W., Dekkers, A. L. M., Bouwman, A. F., Ludwig, W. & Harrison, J. Estimation of global river transport of sediments and associated particulate C, N, and P. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy. 19, GB4S05. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002453 (2005).

Seitzinger, S. et al. Denitrification across landscapes and waterscapes: A synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 16, 2064–2090. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2064:dalawa]2.0.co;2 (2006).

Krishna, M. S. et al. Export of dissolved inorganic nutrients to the northern Indian Ocean from the Indian monsoonal rivers during discharge period. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 172, 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.10.013 (2016).

Krishna, M. S. et al. Fluxes of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen to the northern Indian Ocean from the Indian monsoonal rivers. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 120, 2067–2080. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JG002912 (2015).

Yan, Y. et al. Increasing riverine export of dissolved organic carbon from China. Glob. Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16819s (2023).

Van Vliet, M. T. H., Florke, M. & Wada, Y. Quality matters for water scarcity. Nat. Geosci. 10, 800–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo3047 (2017).

Strokal, M. et al. Urbanization: An increasing source of multiple pollutants to rivers in the 21st century. npj Urban sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00026-w (2021).

Nixon, S. W. Coastal marine eutrophication: A definition, social causes, and future concerns. Ophelia 41, 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00785236.1995.10422044 (1995).

Howarth, R. et al. Coupled biogeochemical cycles: Eutrophication and hypoxia in temperate estuaries and coastal marine ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 18–26 (2011).

Maure, E., Terauchi, G., Ishizaka, J., Clinton, N. & DeWitt, M. Globally consistent assessment of coastal eutrophication. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26391-9 (2021).

Jaga, P. K. & Patel, Y. An Overview of fertilizers consumption in India: Determinants and outlook for 2020-A review. Int. J. Sci. Engg. Tech. 1, 285–291 (2012).

Naqvi, S. W. A. et al. Increased marine production of N2O due to intensifying anoxia on the Indian continental shelf. Nature 408, 346–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/35042551 (2000).

Gomes, H. D. R. et al. Massive outbreaks of Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the Arabian sea due to spread of hypoxia. Nat. Commun. 5, 4862. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5862 (2014).

Bristow, L. A. et al. N2 production rates limited by nitrite availability in the Bay of Bengal oxygen minimum zone. Nat. Geosci. 10, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2847 (2017).

Gupta, L. P., Subrahmanian, V. & Ittekkot, V. Biogeochemistry of particulate organic matter transported by the Godavari river India. Biogeochem. 38, 103–128 (1997).

Gaillardet, J., Dupre, B., Louvat, P. & Allegre, C. J. Global silicate weathering and CO2 consumption rates deduced from the chemistry of large rivers. Chem. Geol. 159, 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00031-5 (1999).

Kendall, C., Silva, S. R. & Kelly, V. J. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic compositions of particulate organic matter in four large river systems across the United States. Hydrol. Proces. 15, 1301–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.216 (2001).

Balakrishna, K. & Probst, J. L. Organic carbon transport and C/N ratio variations in a large tropical river: Godavari as a case study India. Biogeochem. 73, 457–473 (2005).

Wu, Y. et al. Sources and distribution of carbon within the Yangtze River system. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 71, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.08.016 (2007).

Bouillon, S. et al. Organic matter sources, fluxes and greenhouse gas exchange in the Oubangui River (Congo River basin). Biogeosci. 9, 2045–2062. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-2045-2012 (2012).

Tamooh, F. et al. Distribution and origin of suspended matter and organic carbon pools in the Tana River Basin. Kenya. Biogeosci. 9, 2905–2920. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-2905-2012 (2012).

Savoye, N. et al. Dynamics of particulate organic matter δ15N and δ13C during spring phytoplankton blooms in a macrotidal ecosystem (Bay of Seine, France). Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 255(27), 41. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps255027 (2003).

Gearing, J.N., (1988) The use of stable isotope ratios for tracing the nearshore-offshore exchange of organic matter. Lecture notes on coastal and estuarine studies, vol. 22. In Jansson, B. O. (Ed.) Coastal Offshore Ecosystem Interactions. Springer-Verlag NewYork 69–101. https://doi.org/10.1029/LN022p0069

Sherin, C. K. et al. New to total primary production ratio (f-ratio) in the Bay of Bengal using isotopic composition of suspended particulate organic carbon and nitrogen. Deep Sea Res. Part I 139, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2018.06.002 (2018).

Ho, P.-C. et al. Carbon and nitrogen isoscape of particulate organic matter in the East China Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 197, 102667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2021.102667 (2021).

Ittekkot, V. & Laane, R. W. P. M. Fate of riverine particulate organic matter. In Biogeochemistry of Major World Rivers, SCOPE 42 (eds Degens, E. T. et al.) 233–242 (John Wiley, 1991).

Smith, D., Simon, M., Alldredge, A. L. & Azam, F. Intense hydrolytic enzyme activity on marine aggregates and implication for rapid particle dissolution. Nature 35, 9139–9141. https://doi.org/10.1038/359139a0 (1992).

Thornton, S. F. & McManus, J. Application of organic carbon and nitrogen stable isotope and C/N ratios as source indicators of organic matter provenance in estuarine systems: evidence from the Tay Estuary. Scotland. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 38, 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.1994.1015 (1994).

Kao, S. J. & Liu, K. K. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope systematic in a human disturbed watershed (Lanyang-His) in Taiwan and the estimation of biogenic particulate organic carbon and nitrogen fluxes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy. 14, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GB900079 (1999).

Altabet, M. A. & Francois, R. Sedimentary nitrogen isotopic ratio as a recorder for surface ocean nitrate utilization, Global Biogeochem. Cycle 8, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-78737-9_12 (1994).

Brandes, J. A., Devol, A. H., Yoshinari, T., Jayakumar, D. A. & Naqvi, S. W. A. Isotopic composition of nitrate in the cen- tral Arabian Sea and eastern tropical North Pacific: A tracer for mixing and nitrogen cycles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1680–1689. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1998.43.7.1680 (1998).

Sarma, V. V. S. S., Krishna, M. S. & Srinivas, T. N. R. Sources of organic matter and tracing of nutrient pollution in the coastal Bay of Bengal. Mar. Poll. Bull. 159, 111477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111477 (2020).

Cole, M. L. et al. Assessment of a d15N isotopic method to indicate anthropogenic eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. J. Environ. Qual. 33, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2004.1240 (2004).

Dailer, M. L., Knox, R. S., Smith, J. E., Napier, M. & Smith, C. M. Using δ 15N values in algal tissue to map locations and potential sources of anthropogenic nutrient inputs on the island of Maui, Hawai’i USA. Mar. Pollu. Bull. 60, 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.12.021 (2010).

Fernandes, M. et al. The use of delta N-15 signatures of translocated macroalgae to map coastal nutrient plumes: improving species selection and spatial analysis of metropolitan datasets. J. Environ. Monit. 14, 2399–2410. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2EM10997B (2012).

Carpenter, E. J., Harvey, H. R., Fry, B. & Capone, D. G. Biogeochemical tracers of the marine cyanobacterium trichodesmium. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 44, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0637(96)00091-x (1997).

Montoya, J. P., Carpenter, E. J. & Capone, D. G. Nitrogen-fixation and nitrogen isotope abundances in zooplankton of the oligotrophic North Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 1617–1628. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2002.47.6.1617 (2002).

Giosan, L. et al. Short communication: Massive erosion in monsoonal central India linked to late Holocene land cover degradation, Earth Surf. Dynam. 5, 781–789. https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-5-781-2017 (2017).

Central Water Commision, 2017. Godavari Basin Meteorological Data Godavari Circle Hyderabad 1–448

Rao, K.L., 1975. India’s water wealth, its assessment, uses and projections. Orient Longman New Delhi 255

Central Water Commission, 2014. Godavari Basin, Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India, 1–187.

Krishna, M. S. et al. Sources, distribution and preservation of organic matter in a tropical estuary (Godavari, India). Estuar. Coasts 38, 1032–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9859-5 (2015).

Suzuki, R. & Ishimaru, T. An improved method for the determination of phytoplankton chlorophyll using N N-dimethylformamide. J. Oceanogr. 46, 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02125580 (1990).

Carritt, D.E., Carpenter, J.H., 1966. Comparison and evaluation of currently employed modifications of Winkler method for determining dissolved oxygen in seawater – a Nasco report. J. Mar. Res. 24, 286. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/1077

Grashoff, K., Ehrhardt, M., Kremling, K., 1992 Methods of Seawater Analysis, 419 Verlag Chemie, New York https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527613984

Parnell, A., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. and Jackson, A.L. 2008. SIAR: Stable Isotope Analysis in R. http://cran.r-roject.org/web/packages/siar/index.html

Parnell, A., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. & Jackson, A. L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes coping with too much variation. PLoS ONE 5, 9672. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009672 (2010).

Sarma, V. V. S. S. et al. Distribution and sources of particulate organic matter in the Indian monsoonal estuaries during monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 2095–2111. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JG002721 (2014).

Dubois, S. et al. Origin and composition of sediment organic matter in a coastal semi-enclosed ecosystem: An elemental and isotopic study at the ecosystem space scale. J. Mar. Sys. 94, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2011.10.009 (2012).

Krishna, M. S., Mukherjee, J., Dalabehera, H. B. & Sarma, V. V. S. S. Particulate organic carbon composition in temperature fronts of the northeastern Arabian Sea during winter. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 123, 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/2018JG004387 (2018).

Connolly, R. M., Gorman, D., Hindell, J. S., Kildea, T. N. & Schlacher, T. A. High congruence of isotope sewage signals in multiple marine taxa. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 71, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.03.021 (2013).

Corbett, P. A., King, C. K. & Mondon, J. A. Tracking spatial distribution of humanderived waste water from Davis Station, East Antarctica using δ15N and δ13C stable isotopes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 90, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.11.034 (2015).

Sarma, V. V. S. S., Patil, J., Shankar, D. & Anil, A. C. Shallow convective mixing promotes massive Noctiluca scintillans bloom in the northeastern Arabian Sea. Mar. Poll. Bull 138, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.054 (2019).

Pradhan, U. K., Wu, Y., Shirodkar, P. V., Zhang, J. & Zhang, G. Multi-proxy evidence for compositional change of organic matter in the largest tropical (peninsular) river basin of India. J. Hydrol. 519, 999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.08.018 (2014).

Hein, T., Baranyi, C., Herndl, G. J., Wanek, W. & Schiemer, F. Allochthonous and autochthonous particulate organic matter in floodplains of the River Danube: The importance of hydrological connectivity. Fresh. Biol. 48, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.00981.x (2003).

Mariotti, A., Gadel, F., Giresse, P. & Mouzeo, K. Carbon isotope composition and geochemistry of particulate organic-matter in the Congo River (Central-Africa) – applications to the study of quaternary sediments off the mouth of the river. Chem. Geol. 86, 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9622(91)90016-P (1991).

Ellis, E. E., Keil, R. G., Ingalls, A. E., Richey, J. E. & Alin, S. R. Seasonal variability in the sources of particulate organic matter of the Mekong River as discerned by elemental and lignin analyses. J. Geophys. Res. 117, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JG001816 (2012).

Tan, F. C. & Edmond, J. M. Carbon isotope geochemistry of the Orinoco Basin. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 36, 541–547. https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.1993.1033 (1993).

Woodwarda, J. & Foster, I. A. N. Erosion and suspending sediment transfer in river catchments: Environmental controls processes and problems. Geogra. 82, 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/20436564.1997.12452621 (1997).

Prahl, F. G., Ertel, J. R., Goni, M. A., Sparrow, M. A. & Eversmeyer, B. Terrestrial organic carbon contributions to sediments on the Washington margin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 3035–3048. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90177-5 (1994).

Bianchi, T. S. The role of teresstrially derived organic carbon in the coastal ocean: A changing paradigm and the priming effect. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 19473–19481. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017982108 (2011).

Montagnes, D. J. S., Berges, J. A., Harrison, P. J. & Taylor, F. J. R. Estimating carbon, nitrogen, protein and chlorophyll a from volume in marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1994.39.5.1044 (1994).

Redfield, A. C., Ketchum, B. H. & Richards, F. A. The influence of organisms on the composition of seawater. In The Sea Vol. 2 (ed. Hill, M. N.) 26–77 (John Wiley and Sons, 1963).

Onstad, G. D., Canfield, D. E., Quay, P. D. & Hedges, J. I. Sources of particulate organic matter in rivers from the continental USA: Lignin phenol and stable carbon isotope compositions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 64, 3539–3546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00451-8 (2000).

Jennerjahn, T. C. et al. Biogeochemistry of a tropical river affected by human activity in its catchment: Brantas River estuary and coastal waters of Madura Strait. Java Indonesia. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 60, 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2004.02.008 (2004).

Lamb, A. L., Wilson, G. P. & Leng, M. J. A review of coastal palaeoclimate and relative sea-level reconstructions using δ13C and C/N ratios in organic material. Ear. Sci. Rev. 75, 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.003 (2006).

Schmidt, M. W. I., Knicker, H. & Kögel-Knabner, I. Organic matter accumulation in Aeh and Bhhorizons of a Podzol–chemical characterization in primary organo-mineral associations. Organ. Geochem. 31, 727–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00045-0 (2000).

Meyers, P. A. Preservation of elemental and isotopic source identification of sedimentary organic matter. Chem. Geol. 114, 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90059-0 (1994).

Cifuentes, L. A., Sharp, J. H. & Fogel, M. L. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry in the delaware estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35, 1102–1115. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1988.33.5.1102 (1988).

Bentaleb, I. et al. Carbon isotopic fractionation by plankton in the Southern Indian Ocean: Relation between δ13C of particulate organic carbon and dissolved carbon dioxide. J. Mar. Sys. 17, 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-7963(98)00028-1 (1998).

Middelburg, J. J. & Nieuwenhuize, J. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in suspended matter and sediments from the Schelde estuary. Mar. Chem. 60, 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4203(97)00104-7 (1998).

Goñi, M. A., Hatten, J. A., Wheatcroft, R. A. & Borgeld, J. C. Particulate organic matter export by two contrasting small mountainous rivers from the Pacific Northwest, U.S.A. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 118, 112–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrg.20024 (2013).

Hatten, J. A., Goni, M. A. & Wheatcroft, R. A. Chemical characteristics of particulate organic matter from a small, mountainous river system in the Oregon Coast Range, USA. Biogeochem. 107, 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9529-z (2012).

Besemer, K. et al. Sources and composition of organic matter for bacterial growth in a large European river floodplain system (Danube, Austria). Org. Geochem. 40, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2008.12.005 (2009).

Kempe, S., Pettine, M., Cauwet, G., 1991 Biogeochemistry of European rivers In Biogeochemistry of world major rivers (Degens ET, Kempe S, Richey JE eds.), SCOPE 42.

Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), 1995.

FAO, 2003 The digitized soil map of the world and derived soil properties (version 3.5); FAO Land and Water Digital Media Series 1, FAO, Rome

Li, T., Li, S., Liang, C., He, B. & Bush, R. T. Erosion vulnerability of sandy clay loam soil in Southwest China: Modeling soil detachment capacity by flume simulation. CATENA 178, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.03.008 (2019).

Hengade, N. & Eldho, T. I. Relative impact of recent climate and land cover changes in the Godavari river basin, India. J. Earth. Sys. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1135-4 (2019).

Silveira, D. M. India Book 1993–94 462 (Classic Publishers, 1993).

Bateman, A. S. & Kelly, S. D. Fertilizer nitrogen isotope signatures. Isotopes Environ. & Health Stud. 43, 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10256010701550732 (2007).

Xiaoyu, N. et al. A novel slow-release urea fertiliser: Physical and chemical analysis of its structure and study of its release mechanism. Biosyst. Eng. 115, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2013.04.001 (2013).

Versino, F., Urriza, M. & García, M. A. Eco-compatible cassava starch films for fertilizer controlled-release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 134, 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.037 (2019).

Savci, S. Investigation of effect of chemical fertilizers on environment. APCBEE Proc. 1, 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcbee.2012.03.047 (2012).

CGWB, 2014. Concept Note on geogenic contamination of ground water in India with a special note on nitrate. Central ground Water Board, Ministry of Water Resources Govt. of India Faridabad

Foster, S. S. D. Assessing and controlling the impacts of agriculture on groundwater—from barley barons to beef bans Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 33, 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1144/qjegh.33.4.263 (2000).

Rahman, A., Mondal, N. C. & Tiwari, K. K. Anthropogenic nitrate in groundwater and its health risks in the view of background concentration in a semi arid area of Rajasthan. India. Sci. Rep. 11, 9279. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88600-1 (2021).

Jayarajan, P. S. K. & Kuriachan, L. Exposure and health risk assessment of nitrate contamination in groundwater in Coimbatore and Tirupur districts in Tamil Nadu, South India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 10248–10261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11552-y (2021).

Shukla, S., and Saxena, A., 2020 Sources and leaching of nitrate contamination in ground water. Curr. Sci. 118 883–891 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27226382

Sarkar, S. et al. Vulnerability of groundwater from elevated nitrate pollution across India: Insights from spatio-temporal patterns using large-scale monitoring data. J. Contam. Hydrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2021.103895 (2021).

Harris, S. J. et al. Isotopic evidence for nitrate sources and controls on denitrification in groundwater beneath an irrigated agricultural district. Sci. Tot. Environ. 817, 152606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152606 (2022).

Kumar, B. S. K., Sridevi, B., Sarma, V. V. S. S., Cardinal, D. & Sebilo, M. Isotopic evidence of denitrified nitrate in groundwater beneath intensive agriculture and exchange with estuary (Godavari, India). ACS EST Water 4, 3521–3531. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.4c00338 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Director, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)-National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa, and the Scientist-In-Charge, NIO-Regional Centre, Visakhapatnam for their support and encouragement. This work is part of the Institutional Project funded by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India.

Funding

The work is part of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India, funded research project (OLP 2011). It is already mentioned in the acknowledgement section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSK and NPCR conceptualized the work and planned for field campaign. SAN, MHKP and ChV S were participated in the field campaign for sample collection and analysis of samples. Original draft of the manuscript was prepared by MSK and, NSR provided land use change and soil OC maps of Godavari basin. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krishna, M.S., Naidu, S.A., Prasad, M.H.K. et al. Role of synthetic fertilizers on stable isotope ratios of particulate organic matter in the Godavari River. Sci Rep 15, 17267 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99286-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99286-0