Abstract

Aiming to address severe sliding mode chattering in traditional sliding mode observer (SMO), high-frequency harmonics in the back electromotive force (EMF), and low rotor position estimation accuracy, this paper proposes an improved adaptive SMO. And considering the characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system—such as high flywheel operating speeds, a wide range of speed variations, and frequent switching of control strategies—the sliding mode surface and reaching law are redesigned. Additionally, a charge and discharge control strategy tailored for the flywheel energy storage system is developed. First, a continuous sigmoid function is established as the sliding mode switching function to accelerate system convergence and mitigate chattering. An integral sliding mode surface and a power reaching law are incorporated into the sliding mode surface function, which not only suppresses chattering but also improves the system’s dynamic response speed. Second, adaptive control of the back EMF is introduced to filter out high-frequency harmonic signals in the estimated extended back EMF, thus avoiding the chattering and phase delay caused by a low-pass filter. An improved phase-locked loop (PLL), which filters out the effects of motor rotation, is introduced to correct the impact of rotor speed variations, further enhancing the accuracy of rotor speed and position estimation. Finally, a simulation model is built on the MATLAB/Simulink platform to validate the practicality and effectiveness of the proposed control strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

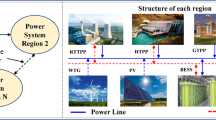

Under the background of accelerating the construction of a new power system in China and supporting the achievement of the “dual carbon” goals, the renewable energy generation industry has rapidly emerged1. However, the inherent intermittency, volatility, and randomness of renewable energy generation have increasingly severe impacts on grid frequency oscillations caused by the large-scale high-proportion integration of renewable energy, exacerbating the burden on thermal power generation for peak shaving and frequency regulation, and posing a serious threat to the safe operation of the power grid2,3. Energy storage, as a key technology for grid integration of renewable energy and promoting the transformation of traditional power grids, has shown broad application prospects4.

Flywheel energy storage technology, due to its advantages such as long service life, high energy density, fast charging and discharging rates, and environmental friendliness5,6,7, has been widely applied in smoothing wind power output, intermittent energy generation, and assisting in grid peak shaving and frequency regulation8. Permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM), with advantages such as small size, high power density, high efficiency, and rapid dynamic response, are commonly used as energy exchange motors in flywheel energy storage systems9.

The control strategies for PMSM can generally be categorized into field-oriented vector control (FOC), intelligent control, model predictive control, and direct torque control10,11,12. Among them, Model Predictive Control (MPC) can directly handle multivariable nonlinear systems and consider constraints during the control process, thereby achieving better dynamic performance and higher control accuracy. However, issues such as the non - fixed switching frequency, online calculation delay, and sensitivity to parameters of this method can degrade the system’s control performance.

To enhance the practicality of the MPC algorithm, Reference13 is based on the deadbeat principle and employs a sliding mode observer (SMO) and a disturbance observer to achieve the rapid selection of the optimal voltage vector, which improves the system’s robustness. Nevertheless, the system design of this method is relatively complex, making it difficult to be widely applied. Reference14 adopts a two - step prediction method to compensate for the delay in the Finite Control Set Model Predictive Current Control (FCS - MPCC), effectively balancing the switching frequency and steady - state performance. However, it is difficult for this method to accurately compensate for the current error value. Considering the optimization problem of no vector switching in the two - step predictive control, Reference15 simplifies the two - step Finite Control Set Model Predictive Current Control strategy and designs a voltage vector positioning scheme based on the dead - beat principle, which is suitable for two control cycles. This provides a new solution for the rapid optimization of the two - step Model Predictive Control (MPC).

Compared with MPC, FOC can achieve precise control of the motor’s flux and torque by decoupling the three-phase currents of the motor, thereby improving the motor’s response speed and control accuracy16. In the FOC method for PMSM, rotor position and speed information need to be obtained through mechanical sensors. However, the use of mechanical sensors reduces system reliability, increases system complexity and cost, and introduces problems such as susceptibility to interference, poor reliability, and difficulties in installation and maintenance. These issues are detrimental to the safe and continuous operation of flywheel energy storage systems17,18,19. To ensure the reliability and accuracy of PMSM control, various sensorless control techniques have emerged as a new direction in motor control research.

The SMO algorithm is widely used in sensorless control systems for motors due to its simple structure, strong robustness, and insensitivity to parameter variations20,21,22. However, the discontinuity of the sign function in traditional SMOs leads to high-frequency chattering near the sliding surface. The high-frequency harmonics in the back EMF signal cause a decrease in the position angle accuracy extracted by the arctangent function23,24,25. In this regard, literature26 proposes a novel fuzzy adaptive sliding mode observer based on boundary layer adaptation. It replaces the discontinuous sign function with a continuous function, introduces a boundary layer parameter, and establishes fuzzy rules to suppress high-frequency chattering on the sliding surface. However, the estimation accuracy is influenced by the magnitude of the current observation error and the smoothness of the boundary layer. Literature27 introduces a variable-speed approaching law, combining an exponential function with the traditional sliding mode reaching law, which partially suppresses the system’s chattering. However, this approaching law has a low convergence rate and slow response, reducing the system’s robustness. Literature28 compensates for rotor position errors using real-time speed estimates and low-pass filter cutoff frequencies but neglects the impact of speed estimation errors on rotor position error compensation. Literature29 propose a SMO with a dual second-order generalized integrator frequency locked loop (DSOGI - FLL). Utilize the DSOGI - FLL and the feedforward term to eliminate the harmonics in the estimated back EMF components. However, the design of the DSOGI - FLL is relatively complex and challenging to implement.

Most current research on SMO algorithms primarily focuses on motor control30, whereas flywheel energy storage systems exhibit a more complex back-to-back structure, high operational speeds of the flywheel and motor, large system inertia, fast charging and discharging rates, and frequent switching of control strategies31,32. When applying SMO algorithms to flywheel energy storage systems, it is necessary to consider factors such as chattering suppression, response speed, and estimation accuracy, while also redesigning the SMO to account for the specific characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system’s charging and discharging control.

This paper addresses the issues such as the difficult installation of sensors for the permanent magnet synchronous motor in the flywheel energy storage system, the severe sliding mode chattering of the traditional sliding mode observer, the presence of a large number of high-frequency harmonics in the back electromotive force, and the low accuracy of rotor position estimation. Accordingly, an improved adaptive sliding mode observer algorithm for the charging and discharging control of the flywheel energy storage system is proposed. The algorithm is redesigned by incorporating the high operational speed, fast charging and discharging rates, and frequent control strategy switching characteristics of the system. Specifically, a continuous and smooth sigmoid function is used to replace the traditional discontinuous sign function in the SMO, which accelerates the convergence speed and reduces high-frequency chattering. The sliding surface function is modified by combining integral design with a power-law reaching law, which helps smooth the torque, reduce steady-state errors, improve the system’s approaching speed, and enhance the stability of both the SMO and the overall system. Adaptive control of back EMF is introduced into the improved SMO to filter high-frequency harmonic signals in the extended back EMF estimation, improving the estimation accuracy of the observer. Rotor speed and position information are extracted using an improved PLL that filters out the effects of motor rotation, correcting the chattering caused by phase lag in traditional SMO and mitigating the impact of motor speed changes on estimation accuracy.

Flywheel energy storage system model

Components of the flywheel energy storage system

The flywheel energy storage system topology studied in this paper is shown in Fig. 1, and consists of a flywheel with large inertia rotor, bearing system, vacuum chamber, housing, PMSM (motor/generator), machine-side converter, DC bus voltage stabilization capacitor, grid-side converter, filtering inductors, and other components.

The PMSM (motor/generator), as the core energy conversion component of the flywheel energy storage system, typically adopts a surface-mounted structure. Its rotor is coaxially connected to the flywheel body, and by controlling the acceleration and deceleration of the motor rotor, energy storage and conversion between electrical and mechanical energy are achieved. During charging, the rotor speed increases, and the motor operates in motor mode, causing the flywheel to accelerate and convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. During discharging, the motor operates in generator mode, with the rotor speed decreasing and the flywheel decelerating, thus converting stored mechanical energy into electrical energy for release. The power converter regulates the motor speed to achieve charging or discharging, and also performs frequency conversion, rectification, and constant voltage control, ensuring that the flywheel energy storage system outputs electrical energy that meets grid requirements.

Mathematical model of permanent magnet synchronous motor

A mathematical model of a three-phase surface-mounted PMSM based on the dq coordinate system is established, and simplification is carried out using coordinate transformation and vector space decoupling methods.

The stator voltage equation of the PMSM is:

where ud and uq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the stator voltage; Rs is the stator resistance; id and iq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the stator current; ωe is the electrical angular velocity; Ψd and Ψq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the stator flux linkage.

The stator flux linkage equation of the PMSM is:

where Ld and Lq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the stator inductance; Ψf is the flux linkage of the permanent magnet.

By substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1), we get:

From Eq. (3), the voltage equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 22 can be obtained. From the figure, it can be seen that the three-phase surface-mounted PMSM mathematical model achieves complete decoupling.

The electromagnetic torque equation of the PMSM is:

where Te is the electromagnetic torque, and pn is the number of pole pairs of the motor.

The mechanical motion equation of the PMSM is:

where ωm is the mechanical angular velocity; J is the moment of inertia; Bm is the damping coefficient; and TL is the load torque.

The energy conversion motor studied in this paper is a three-phase surface-mounted PMSM, where the stator inductances satisfy Ld=Lq, In this case, the electromagnetic torque is proportional to the q-axis equivalent current iq, which exhibits the speed control characteristics of a DC motor.

The flywheel rotor serves as the energy storage component of the system. According to mechanical principles, the maximum energy that the flywheel can store or release is given by:

where ωmax and ωmin are the maximum and minimum mechanical angular velocities of the flywheel rotor, respectively. From Eq. (6), it can be seen that, with a constant moment of inertia J, the storage or release of energy in the flywheel energy storage system can be achieved by varying the angular velocity of the flywheel rotor.

Flywheel energy storage system with sensorless control

Traditional sliding mode observer

The state equation of the three-phase surface-mounted PMSM based on the αβ coordinate system is:

where iα and iβ represent the α-axis and β-axis co mponents of the stator current, respectively; L is the stator inductance; uα and uβ are the α-axis and β-axis components of the stator voltage; eα and eβ are the α-axis and β-axis components of the extended back EMF, which can be expressed as:

where θe is the rotor position angle of the motor.

From Eq. (8), it can be seen that the rotor position and speed information are contained in the extended back EMF of the motor.

To obtain the estimated value of the extended back EMF, the design of the traditional SMO is as follows:

where ^iα and ^iβ are the observed values of the stator current in the α-axis and β-axis components; vα and vβ are the control laws of the SMO for the α-axis and β-axis.

By subtracting Eq. (7) from Eq. (9), the stator current error equation can be obtained as:

where ~iα=^iα-iα and ~iβ=^iβ-iβ represent the current errors.

The sliding surface is designed as sα=~iα and sβ=~iβ, then the sliding mode control law is:

where k is the switching gain, and k > max (|eα|, |eβ|).

When the system state variables reach the sliding surfaces sα=0 and sβ=0, the extended back EMF can be expressed by Eq. (9) as:

Due to the discontinuity of the switching function sgn in the traditional SMO, an additional low-pass filter is required to filter and extract the extended back EMF. The filtered signal is given by:

where ^eα and ^eβ represent the estimated values of the extended back EMF along the α-axis and β-axis, ωc is the cutoff angular frequency of the low-pass filter, and F is the complex frequency.

When the high-frequency switching signal passes through the low-pass filter, the estimated values of the extended back EMF will experience a phase delay. Typically, the arctangent function is used to extract the rotor position information and perform phase compensation.

where ^θe is the estimated rotor position, and ^ωe is the estimated angular velocity.

The overall implementation principle of the traditional SMO is shown in the block diagram of Fig. 3.

Due to the high-frequency oscillations of the extended back EMF observation values in the sliding mode caused by the sliding surface and control law selected by the traditional SMO, and the phase lag introduced by the low-pass filter, the use of the arctangent function for rotor position estimation and phase compensation reduces the observation accuracy of the system. Therefore, this paper redesigns the sliding mode surface and reaching law, considering the high operating speed of the flywheel energy storage system, rapid charging and discharging rates, and frequent control strategy switching. Additionally, the paper incorporates an adaptive back EMF adaptive law and an improved PLL to estimate the rotor speed and position angle.

Design of the improved adaptive sliding mode observer

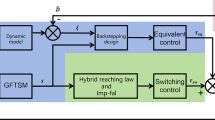

The block diagram of the implementation principle of the improved SMO designed in this paper is shown in Fig. 4.

To address the issues of high-frequency oscillations near the sliding surface and low observation accuracy in the traditional SMO, a continuous sigmoid function is proposed to replace the sgn function as the switching function of the improved sliding mode observer. The sigmoid function is continuously differentiable in the real - number domain, and its function graph near the zero point is a continuous and smooth curve. The continuous - change characteristic of the sigmoid function enables the system to exhibit continuous feedback control within the inner layer of the error boundary. Its approaching process is smoother, which can effectively suppress the high - frequency chattering problem caused by state switching.

The sigmoid function used in this paper is:

where a is a normal constant, and x is the boundary layer thickness. The graph of the sigmoid function is shown in Fig. 5.

Based on the theoretical analysis of the sliding mode variable structure and the verification of simulation experiments, this paper selects appropriate parameters for the sigmoid function to adjust the slope of the function curve and the thickness of the boundary layer, so as to improve the control accuracy and response speed of the system. In order to further reduce the steady-state error of the system, weaken the chattering, and smooth the torque fluctuation of the motor, this paper designs the sliding mode surface function and the sliding mode reaching law in combination with the charging and discharging characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system. By combining the integral sliding mode surface with the power sliding mode reaching law, the stability and accuracy of the observer are enhanced.

In this paper, appropriate parameters for the sigmoid function are selected through experiments to adjust the slope and boundary layer thickness of the function curve, thereby improving the system’s control accuracy and response speed. To further reduce the system’s steady-state error, weaken the oscillations, and smooth the motor torque fluctuations, a sliding surface and sliding mode approaching law are designed based on the charge and discharge characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system. An integral sliding surface combined with a power-law sliding mode approaching law is used, which enhances the stability and accuracy of the observer.

The integral sliding surface designed in this paper is:

where c1 and c2 are constants greater than zero, and ~iα and ~iβ are the system state errors.

To ensure that the system states have good approaching characteristics and to improve the dynamic response speed, the power-law approaching law designed in this paper is:

where ε > 0, 0 < γ < 1.

The combination of the sigmoid switching function, integral sliding mode function, and power-law sliding mode reaching law, used as the control law for the improved SMO, allows Eq. (12) to be rewritten as:

To verify the effectiveness of the improved sliding mode control law proposed in this paper, based on the Lyapunov stability principle, the Lyapunov equation is established as follows:

In the equation: V is the Lyapunov function.

Taking the derivative of Eq. (19) gives:

According to the stability conditions, the following must be satisfied:

Substituting Eq. (17) into (20), we can obtain:

In the equation: both k and ε are constants greater than zero. When s > 0, sigmoid(s) > 0, then s⋅sigmoid(s) > 0. At this time, \(s\dot {s}<0\), The system satisfies the stability condition. When s < 0, sigmoid(s) < 0, and s⋅sigmoid(s) > 0 still holds. Therefore, the system still satisfies the stability condition of \(s\dot {s}<0\), Thus, the improved sliding mode control law can ensure that the system enters the sliding mode.

Design of back EMF adaptive law

To filter out the high-frequency harmonic signals contained in the back EMF and further improve the estimation accuracy of the improved SMO, a back EMF adaptive law based on model reference adaptive identification is introduced. This avoids the significant phase delay of the back EMF signal caused by using low-pass filters in traditional SMO.

Taking the derivative of Eq. (8) yields:

Based on Eq. (24), the adaptive design for the back EMF is formulated as:

where λ > 0 is the negative feedback gain, ^eα and ^eβ represent the estimated values of the extended back EMF, and ^ωe is the estimated angular velocity.

Taking the difference between Eqs. (24) and (25), the back-EMF error equation can be obtained as:

where ~eα=^eα-eα and ~eβ=^eβ-eβ represent the estimation errors of the back EMF on the α-axis and β-axis, ~ωe=^ωe-ωe represent the angular velocity estimation error.

To verify the effectiveness of the adaptive back EMF law designed for the improved SMO in this paper, and based on the Lyapunov stability criterion, the Lyapunov function is defined as:

Taking the derivative of Eq. (27) and substituting Eq. (26) into it yields:

Equation (28) satisfies the Lyapunov stability theorem. Therefore, the adaptive back EMF law designed for the improved SMO in this paper is asymptotically stable.

Rotor position and speed estimation based on improved PLL

Traditional SMO typically use the arctangent function to obtain rotor position and angle estimates, which involves complex calculations, and the division operation further amplifies the high-frequency chattering in the back EMF. Therefore, in this paper, a PLL is used to obtain rotor position and angle estimates from the motor’s back EMF, with improvements made by adding a rotation elimination component to mitigate the impact of motor speed on estimation accuracy.

The structural diagram of the PLL is shown in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, the back EMF error signal of the improved PLL is obtained as:

When the rotor error |^θe-θe|<π/6, it can be approximately assumed that sin(θe-^θe)=θe-^θe. Consequently, the electrical angular velocity and rotor position angle of the motor can be estimated.

In summary, the implementation flowchart of the improved adaptive sliding mode observer algorithm proposed in this paper is shown in Fig. 7.

Charge and discharge control strategy for flywheel energy storage system

The charging and discharging control technology is crucial for the flywheel energy storage system’s participation in grid power regulation and renewable energy power smoothing output. Most of the inverter drive control technologies can be adapted and applied to the charging and discharging control of the flywheel energy storage system, but they need to be modified and improved in conjunction with the operational conditions of the flywheel itself. Flywheels typically operate in high-speed rotation, and mechanical sensors are limited in installation, making it difficult to sense the high-speed rotating flywheel. Therefore, sensorless control technology is preferred. Furthermore, the PMSM is the core of energy exchange in the flywheel energy storage system, and the accuracy and speed of the motor control strategy determine the overall charging and discharging control performance of the system.

Among the existing motor control techniques, the advantage of FOC is that it decouples the three-phase currents of the motor into two independent current components, which separately control the motor’s torque and flux, helping to improve the motor’s response speed and control accuracy. Therefore, this paper adopts a method combining FOC with idref =0 and space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) as the control strategy for the PMSM in the flywheel energy storage system.

Machine-side control strategy of the flywheel energy storage system

The flywheel energy storage system adopts a control strategy combining FOC with idref =0 and space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) on the machine side. This strategy enables the speed control system of the PMSM to achieve fast response speed, high speed accuracy, and a wide speed regulation range. It simplifies and decouples the mathematical model of the PMSM, resulting in a linear relationship between current and torque. Consequently, speed control can be achieved by controlling the current. The corresponding control equations are as follows:

where nref and n represent the reference speed and the actual speed, respectively. Pdref and P denote the system power reference value and the actual power, respectively. idref and iqref are the reference currents for the d-axis and q-axis of the motor, respectively. Kp and Ki are the proportional and integral coefficients of the PI controllers in the various control loops.

To achieve accurate control of motor speed, reduce costs, and improve the system’s environmental adaptability, this paper proposes an improved SMO to replace sensors in obtaining the electrical angular speed and position angle information of the motor rotor. During charging, the machine-side control adopts a dual-PI control structure with an outer speed loop and an inner current loop. The speed outer loop calculates the q-axis reference current iqref by comparing the reference speed and the observed speed.

During discharging, the machine-side control adopts a dual-PI control structure with an outer power loop and an inner current loop to achieve constant-power discharging. The power outer loop calculates the q-axis reference current iqref by comparing the reference power and the actual power. The current reference value is then compared with the d-axis and q-axis current components id and iq, of the motor. The PI controller generates the voltage output values ud and uq. which are transformed into the αβ coordinate system as uα and uβ, respectively. These are used as inputs to the SVPWM module to control the state of the machine-side inverter, thereby regulating the motor’s charging and discharging operation. The control block diagram is shown in Fig. 8.

Grid-side control strategy for the flywheel energy storage system

The grid-side control strategy of the flywheel energy storage system combines grid voltage-oriented vector control and SVPWM (Space Vector Pulse Width Modulation) technology. This strategy converts the unstable AC power output from the permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) into stable AC power for transmission to the grid while maintaining a stable DC bus voltage. The system operates at a unit power factor, with isqref =0. The corresponding control equations are as follows:

where isdref and isqref represent the reference currents for the d-axis and q-axis of the grid, respectively. isd and isq are the actual currents for the d-axis and q-axis of the grid, respectively. esd and esq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the grid voltage, respectively. Ls is the filtering inductance. Ksp and Ksi are the proportional and integral coefficients of the PI controllers in the various control loops. ωs is the grid angular frequency.

The control block diagram is shown in Fig. 9. During both charging and discharging, the grid-side control adopts a dual-PI control structure with an outer voltage loop and an inner current loop to maintain a stable DC bus voltage. The outer voltage loop calculates the d-axis reference current isdref based on the reference and actual DC bus voltage values.

The reference current values are compared with the actual d-axis and q-axis current components isd and isq respectively. The PI controllers then process these differences to generate voltage output values usd and usq. These voltages are transformed into the αβ-coordinate system to obtain usα and usβ, which serve as inputs to the SVPWM module. to controls the grid-side converter states, thereby managing the flywheel energy storage system’s charging and discharging operations during grid connection.

Simulation verification

In order to verify the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed charge and discharge control strategy for the flywheel energy storage system based on the improved SMO, this section builds a simulation model using the MATLAB/Simulink platform. It mainly includes the permanent magnet synchronous motor module, speed loop control module, current loop control module, SVPWM modulation module, and improved SMO module.

The parameters of the improved adaptive sliding mode observer used in the simulation are shown in Table 1. The system simulation time is 4s, the simulation step size is set to 5 × 10⁻⁵s. The vector control strategy with id=0 is adopted, and the reference rotational speeds are set to 1000 rpm and 1200 rpm. The parameters of the permanent magnet synchronous motor are shown in Table 2.

The parameter tuning process of the sliding mode observer in this paper is completed through theoretical analysis and simulation experiment debugging. The coefficients c1 and c2 of the integral sliding mode surface function are determined by the pole assignment method and simulation experiment debugging. The lower limits of ε and k are determined through Lyapunov stability analysis, and they are continuously adjusted through simulations. The values of a and x are determined according to the graph of the sigmoid function and combined with the operating characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system. Lyapunov stability analysis is used to determine the lower limits of the parameters ε and k of the sliding mode control law, and continuous adjustments are made through simulations. The flow chart of the sliding mode parameter tuning is shown in Fig. 10.

Speed estimation

Figures 11(a) and 11(b) show the speed tracking graphs of the traditional SMO and the improved adaptive SMO, respectively, during the motor’s no-load operation at 1000 rpm and when the motor’s no-load speed suddenly changes to 1200 rpm at 1.0s.

From Fig. 11(a), it can be seen that the steady-state speed error range of the traditional SMO at a motor speed of 1000 rpm is [-18, 19] rpm, and the steady-state speed error range at a motor speed of 1200 rpm is [-19, 20] rpm. From Fig. 11(b), it can be seen that the steady-state speed error of the improved adaptive SMO at a motor speed of 1000 rpm is approximately [-0.4, 0.4] rpm, and the steady-state speed error at a motor speed of 1200 rpm is approximately [-0.4, 0.5] rpm.

Figure 12 shows the speed tracking diagram of the charging and discharging process of the flywheel energy storage system based on the improved adaptive sliding mode observer.

It can be seen from Fig. 10 that when the motor is operating at a high rotational speed of 10,000 rpm, the range of the rotational speed steady-state error is [-0.5, 2.5] rpm, which is approximately 0.03% of the overall value. Therefore, the improved adaptive sliding mode observer can still achieve an accurate estimation of the high operating rotational speed of the motor.

Analysis shows that the improved adaptive sliding mode observer proposed in this paper reduces the speed tracking error from the traditional 2–0.04% when the motor operating speed is 1000 rpm. Moreover, when the motor operates at 10,000 rpm, the error is only 0.03%. This verifies that the improved adaptive sliding mode observer achieves more accurate speed tracking with smaller errors.

Rotor position estimation

Figures 13(a) and 13(b) show the rotor position angle estimation error diagrams of the traditional sliding mode observer and the improved adaptive sliding mode observer when the motor is operating no-load at a speed of 1200 rpm. Moreover, a quantitative analysis of the rotor position angle error has been carried out from the perspective of the tracking time scale.

As can be seen from Fig. 13(a), the tracking delay of the traditional sliding mode observer for the position angle of the motor rotor is 0.00045s, which is a relatively long delay. That is to say, the accuracy of the position angle estimation is low, and the deviation is large.

As can be seen from Fig. 13(b), the tracking delay of the improved adaptive sliding mode observer for the position angle of the motor rotor is 0.0003s, which is a relatively short delay. That is to say, the accuracy of the position angle estimation is improved, and the deviation is small. Compared with the estimation accuracy of the traditional sliding mode observer, it is improved by approximately 66.6%. Through analysis, it can be known that the improved adaptive sliding mode observer method proposed in this paper can track the rotor position angle more rapidly and with smaller errors. This improvement enables precise control of the permanent magnet synchronous motor, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the control of the energy exchange between the flywheel energy storage system and the power grid.

Flywheel energy storage system charge and discharge simulation

The simulation parameters for the flywheel energy storage system are shown in Table 3.

In this paper, a constant torque charging method is used, with a target speed of 10,000 rpm. After 3.4 s of simulation, the charging process is completed, and the target speed is maintained for 0.4 s. During the charging and holding phases, the DC bus voltage remains stable with minimal fluctuation, with the fluctuation range around [0, 5] V, which is 0.625% of the DC bus voltage. This verifies the effectiveness of the grid-side charging control strategy used in this paper. During the charging process, the flywheel speed steadily rises to 10,000 rpm, validating the effectiveness of the machine-side charging control strategy based on the improved adaptive SMO replacing mechanical sensors. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 14.

The simulation from 3.8s to 4.3s represents the discharging process, and the simulation results are shown in Fig. 15. During the discharging process, the flywheel speed continuously decreases from 10,000 rpm to 5,800 rpm, with a discharge depth of 66.36%. The system outputs power to the grid using a constant power discharging method. During the discharging process, the DC bus voltage fluctuates within a range of approximately5,6 V, which is 0.75% of the DC bus voltage.

As the motor speed gradually decreases, the electromagnetic torque and three-phase motor current increase. The output power quickly reaches and maintains 600 kW, ensuring a constant power output to the grid. This is shown in Figs. 15(c) and 15(d). The simulation results verify the effectiveness of the machine-side discharging control, achieving stable active power output, and confirm the effectiveness of the grid-side discharging control.

Conclusion

To ensure the rapidity, stability, and accuracy of the charging and discharging control of the flywheel energy storage system, this paper analyzes the shortcomings of the traditional SMO and, considering the operating characteristics of the flywheel energy storage system, proposes a charging and discharging control strategy based on the improved adaptive SMO. This strategy aims to reduce system oscillations and improve the precision of the control system. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) By redesigning the sliding surface and reaching law of the SMO algorithm based on the characteristics of the charging and discharging operation of the flywheel energy storage system, the system’s response speed is accelerated and chattering is reduced. The estimation accuracy of the improved adaptive SMO is enhanced through an back EMF adaptive law and an improved PLL. Compared with the traditional SMO, the speed error is reduced from 2 to 0.04%, and the position angle tracking delay is reduced from 0.00045s to 0.0003s.

(2) On the machine side, a speed/power outer loop and current inner loop control strategy were implemented for the flywheel energy storage system to achieve a constant 600 kW power discharge. On the grid side, a voltage outer loop and current inner loop control strategy were used to maintain a stable DC bus voltage of 800 V. Throughout the entire charge and discharge process, the DC bus voltage remained stable with minimal fluctuation. The maximum fluctuation range was [0, 6] V, approximately 0.75% of the DC bus voltage. This performance meets the grid voltage fluctuation requirements, and the voltage regulation effect is excellent.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Han, X., Li, T. & Zhang, D. New issues and key technologies in the planning of new power systems under the dual carbon target. High. Voltage Technol. 47(09), 3036–3046 (2021).

Zhao, J., Wang, M. & Zhao, B. Neural network-based integrated reactive power optimization study for power grids containing large‐scale wind power. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18(16), 2587–2603 (2024).

Liu, C. & Yin, S. Q. X. Experimental study on the feasibility of isobaric compressed air energy storage as wind power side energy storage. Appl. Energy. 364, 123129–123141 (2024).

Wang, X., Zhou, J. & Qin, B. Coordinated power smoothing control strategy of Multi-Wind turbines and energy storage systems in wind farm based on MADRL. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy. 15(1), 368–380 (2024).

Zhou, W., Torres, R. E. & Wang, Y. DQ impedance-decoupled network model-based stability analysis of offshore wind power plant under weak grid conditions. IET Power Electron. 13(13), 2715–2729 (2020).

Lee, J., Jeong, S. & Han, Y. H. Concept of cold energy storage for superconducting flywheel energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21(3), 2221–2224 (2011).

Ji, W. et al. Applications of flywheel energy storage system on load frequency regulation combined with various power generations. Rev. Renew. Energy. 223, 119975–119986 (2024).

Zhao, H. et al. Review of energy storage system for wind power integration support. Appl. Energy. 137, 545–553 (2015).

Xiang, B., Wang, X. & Wong, W. Process control of charging and discharging of magnetically suspended flywheel energy storage system. J. Energy Storage. 47, 103629–103635 (2022).

Petkar, S. G. Thippiripati. A novel Duty-Controlled DTC of a surface PMSM drive with reduced torque and flux ripples. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70(4), 3373–3383 (2023).

Brosch, A., Wallscheid, O. & Böcker, J. Model predictive torque control for Permanent- magnet synchronous motors using a Stator- fixed harmonic flux reference generator in the entire modulation range. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 38(4), 4391–4404 (2023).

Hoai, H. K., Chen, S. C. & Than, H. Realization of the sensorless permanent magnet synchronous motor drive control system with an intelligent controller. Electronics 9(2), 365 (2020).

Li, T., Sun, X., Yao, M., Guo, D. & Sun, Y. Improved finite control set model predictive current control for permanent magnet synchronous motor with sliding mode observer. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 10(1), 699–710 (2024).

Li, T., Sun, X., Yang, Z. & Lei, G. Simplified Two-Step model predictive control with fast voltage vector search. IEEE Trans. Industrial Electron. 72(4), 3303–3312 (2025).

Li, T. et al. Finite-Control-Set model predictive control of permanent magnet synchronous motor drive Systems—An overview. IEEE/CAA J. Automatica Sinica. 9(12), 2087–2105 (2022).

Wang, X. & Suh, S. A nonlinear time–frequency control based FOC for permanent magnet synchronous motors. Int. J. Dynamics Control. 9(1), 179–189 (2020).

Yao, X., Lin, C. & Xing, J. Transient response characteristics improvement of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on enhanced linear active disturbance rejection sensorless control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 38(4), 4378–4390 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Control method for flywheel energy storage system based on improved sliding mode observer. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 34(1), 71–78 (2014).

Mansour, M., Mansouri, M., Bendoukha, S. & Faouzi, M. A grid-connected variable-speed wind generator driving a fuzzy-controlled PMSG and associated to a flywheel energy storage system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 180, 106137–106141 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Speed control strategy of Low-Cost modular permanent magnet synchronous linear motor based on sliding mode vector tracking observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59(1), 866–872 (2023).

Li, Z., Zhou, S., Xiao, Y. & Wang, L. Sensorless vector control of permanent magnet synchronous linear motor based on Self-Adaptive Super-Twisting sliding mode controller. IEEE Access. 7, 44998–45011 (2019).

Ullah, A. et al. Robust speed control of permanent magnet synchronous motor drive system using Sliding-Mode disturbance Observer-Based Variable-Gain Fractional-Order Super-Twisting Sliding-Mode control. Fractal Fract. 8(7), 368–368 (2024).

Hu, Q., Liu, L., Zhang, C., Cheng, L. & Researching for Sensorless Control of PMSM Based on a Novel Sliding Mode Observer. 3rd International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), 2018, Singapore, Singapore, 542–547. (2018).

Liu, Y. Disturbance-Observer-Based Second-Order Sliding-Mode position control for Permanent-Magnet synchronous motors: A continuous twisting Algorithm-Based approach. Energies 17(12), 2974–2981 (2024).

Luan, M., Ruan, J., Zhang, Y., Yan, H. & Wang, L. An improved adaptive Finite-Time Super-Twisting sliding mode observer for the sensorless control of permanent magnet synchronous motors. Actuators 13(10), 395–409 (2024).

Yao, G., Wang, X., Wang, Z. & Xiao, Y. Senseless control of permanent magnet synchronous motors based on new fuzzy adaptive sliding mode observer. Electronics, 12(15), 3266–3276 (2023).

Han, J., Wu, Z. & Xu, D. Sensorless control of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on SFF-PLL. Combination Mach. Tools Automated Process. Technol. 10, 160–163 (2023). 168.

Jiang, T., Ni, R. & Gu, S. A Study on Position Estimation Error in Sensorless Control of PMSM Based on Back EMF Observation Method. 24th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Gyeongju,2021, Korea 1999–2003. (2021).

Sreejith, R. & Singh, B. Sensorless predictive current control of PMSM EV drive using DSOGI-FLL based sliding mode observer. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 68(7), 5537–5547 (2021).

Yao, G., Cheng, Y., Wang, Z. & Xiao, Y. Study on a second-order adaptive sliding-mode observer control algorithm for the sensorless permanent magnet synchronous motor. Processes 11(6), 1636–1645 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Optimized charging control strategy for flywheel energy storage system based on nonlinear disturbance observer. J. Electr. Eng. 38(6), 1506–1518 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Linear robust discharge control for flywheel energy storage system with RLC filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 58(5), 6175–6189 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyong Xiao and Zhihao Han wrote the main manuscript text; Shiyong Xiao: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Zhihao Han: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. Guowei Cai: Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision. Zhihui Liu: Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Software, Validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, S., Han, Z., Cai, G. et al. Design of an improved adaptive sliding mode observer for charge/discharge control in flywheel energy storage systems. Sci Rep 15, 14838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99386-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99386-x