Abstract

One of the key issues affecting the efficient extraction of coal seam gas is the instability and collapse of extraction boreholes. To investigate the impact of collapsed coal particles on gas flow, a simulation system for gas extraction in collapsed boreholes was established. Based on the characteristics of gas flow resistance distribution within the borehole, the effects of coal particle size and collapse location on gas extraction were investigated. Furthermore, borehole types were categorized according to extraction efficiency. The study revealed that smaller sizes of the collapsed coal particles in the borehole result in higher resistance and complexity in gas flow. The closer the position of the borehole collapse is to the borehole opening, the more obvious the influence of the particle size of the collapsed coal particles on the gas extraction efficiency. The total extraction flow rate and peak concentration of the collapsed borehole decrease as the particle size of the collapsed coal decreases and the position of the borehole collapse gradually approaches the borehole opening, while the residual gas concentration in the coal seam shows the opposite trend. The gas extraction time is jointly influenced by the particle size of the collapsed coal particles and the collapse position. When the collapse occurs at the bottom of the borehole, the gas extraction time prolongs as the particle size of the collapsed coal particles decreases. When the collapse occurs in the middle of the borehole or at the borehole opening, the gas extraction time first increases and then decreases as the particle size decreases. In the evaluation of gas extraction efficiency across different types of unstable boreholes, a score lower than 1.0 indicates a Type I collapsed borehole, while a score higher than 1.0 indicates a Type II collapsed borehole. The research results are helpful to optimize the gas extraction strategy and are of important reference value for the smooth extraction of coal seam gas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In coal mining, coal seam gas poses a significant hazard to operations. If not effectively controlled and managed, it can lead to serious incidents such as mine gas explosions and fires1,2,3. Coal seam gas extraction is the primary approach for gas control and utilization in coal mines, but the instability and collapse of extraction boreholes severely hinder the efficiency of gas extraction from coal seams4,5,6. Boreholes in deep, soft coal seams are particularly prone to instability and collapse7. And with the growth of the hole formation time, the drill hole will be subject to the role of coal body stress around the hole, resulting in different sizes of coal debris and coal particles fall into the extraction borehole to form a plugged hole8,9. The collapsed coal narrow the gas flow pathways, preventing effective extraction of gas10. Therefore, studying the impact of different collapse locations and various collapsed coal particle sizes on gas extraction in boreholes provides an important reference for ensuring smooth and efficient gas extraction.

At present, many experts and scholars have carried out a large number of studies on the mechanism of instability and deformation of boreholes11,12, not only studied the damage forms and instability characteristics of the coal body near the bottom and wall of the borehole13, but also analysed the characteristics of the secondary stress elasticity and plasticity distribution of the surrounding rock of the borehole obtained14. In addition, Guo et al.15 conducted uniaxial compression tests on intact coal specimens and borehole-containing coal samples, analyzing the influence of boreholes on the deformation and failure characteristics of coal. These studies showed that borehole instability is a complex mechanical process, which is closely related to the nature of the coal body itself and the state of the ground stress. Borehole instability is caused by the stress of the coal body exceeding its own strength16, and the distribution characteristics of the plastic and fracture zones provide theoretical support for the subsequent study of the scope of borehole instability and understanding of the mechanical process of borehole instability.

In order to investigate the evolution characteristics and instability state of unstable boreholes, the scholars introduced the Hoek-Brown strength criterion and geological strength index (GSI)17, assessed the overall permeability of coal reservoirs, and analyzed the stability of gas extraction boreholes18. Zhang et al. analyzed the mechanism of deformation and instability of soft coal seams, and proposed three deformation destabilisation modes of soft coal seams, i.e., intact boreholes, collapsed boreholes, and plugged boreholes19. He et al.20 used numerical simulations to reveal the creep deformation behavior of boreholes. Li et al.21 developed a borehole deformation and failure testing system, and through the use of similar materials, conducted experimental testing on the entire process of borehole deformation and failure. The above study on the judgement criteria of instability damage of extraction boreholes and the classification method of unstable boreholes can help to understand the characteristics of unstable boreholes from different perspectives. It is clarified that the effects of various extraction parameters, such as extraction concentration, extraction time, and flow rate, need to be considered in the classification of unstable boreholes in order to more accurately assess the effects of different types of boreholes on gas extraction.

In the study of gas flow processes in porous media, Ruan et al.22 characterised the relationship between permeability and porosity, and derived a series of formulas linking permeability to porosity, particle size, specific surface area, tortuosity and other parameters based on the Kozeny-Carman equation 23. Schulz et al.24 provides easy-to-use quantitative porosity-permeability relationships based on representative single-grain, plate, block, and prismatic soil structures, porous networks, and true geometries obtained from CT data. Liu, Y et al.25 introduced the modified Burgers creep model into the discontinuous embedment model for multiple particle sizes and developed a prediction model in combination with the KC equation. For rod proppants, a fracture conductivity model under rod proppants was developed based on the fracture width and permeability models26. These achievements provide important theories and methods for the study of fracture conductivity under particles of various sizes and shapes. Zhang et al.27,28 studied the change of pore structure caused by particle loss during seepage, and gave a quantitative expression for the change of porosity. Ma et al.29 verified the influence of particle size on the inertia effect in the experiment, and found that the geometry of the pore structure has a great influence on the flow behaviour of the fluid in the crushed rock, which provides a reference basis for the study of seepage characteristics of the crushed coal rock body. Through the previous research, the influence of permeability, porosity, particle size and other factors on gas flow can be more comprehensively understood, which provides a theoretical basis for the in-depth analysis of gas flow resistance.

In summary, considerable advancements have been made in the research concerning gas extraction from unstable collapse boreholes. Nevertheless, the majority of studies have focused on the mechanical analysis of borehole instability and the elucidation of collapse mechanisms. The simulation of unstable boreholes has typically been limited to describing borehole shrinkage by reducing the borehole radius, with insufficient investigation into the gas flow resistance caused by collapsed coal particles within the borehole. In response to the practical challenges of deformation and instability in coal seam gas extraction boreholes, this study employs a self-developed simulation test system specifically designed for gas extraction from unstable boreholes. Through the system, simulation experiments are conducted to investigate several common forms of borehole deformation and instability. The experiments explore the effects of different sizes and locations of collapsed coal particles within the borehole on gas flow resistance and extraction efficiency. Based on the extraction performance, we categorize unstable collapse boreholes to provide a foundation for improving gas extraction efficiency.

Borehole instability mechanism and gas flow resistance characteristics in borehole

Stress distribution around collapsed boreholes

Borehole instability refers to the dynamic instability phenomenon caused by the redistribution of the stress field in the gas-bearing coal around the borehole under external disturbances30. The primary cause of borehole wall collapse is that the stress around the coal body exceeds the strength of the coal itself, leading to shear failure. Based on the stress state and failure modes of the coal body at the borehole wall, the Mohr-Coulomb strength criterion has been selected as the strength criterion for borehole wall collapse and instability31.

After drilling, the gas extraction borehole disturbs the original stress equilibrium of the coal body, causing deformation, displacement, or even failure. This results in the formation of a fractured zone, plastic zone, and elastic zone around the borehole, gradually extending outward from the borehole center32. Following the completion of the borehole, the concentrated stress causes the surrounding coal to transition from an elastic state to a plastic state, eventually leading to the formation of a fractured zone. Over time, the deformation in the fractured and plastic zones increases. When the cohesive and frictional forces between coal blocks are no longer sufficient to resist the deformation pressure and weight of the internal coal mass, the fragmented coal around the borehole falls into the borehole itself.

By analyzing the radial stress and radial strain at the boundary of the plastic zone and the fracture zone, the radius of the plastic zone and the fracture zone33 are obtained as follows:

In the equation, \(\:{R}_{s}\) represents the radius of the plastic zone, m; \(\:{R}_{b}\) denotes the radius of the fractured zone, m; \(\:{R}_{0}\) is the borehole radius, m; \(\:M=\frac{1+{sin}\phi\:}{1-{sin}\phi\:}\), \(\:{S}_{b}=\frac{2{C}_{b}\text{cos}\phi\:}{1-{sin}\phi\:}\), φ is the internal friction angle of coal, (°); \(\:{{\epsilon\:}_{r}}^{{R}_{s}}\) represents the radial elastic strain in the fractured zone; \(\:{{\epsilon\:}_{\theta\:}}^{{R}_{s}}\) denotes the tangential strain at the boundary between the elastic and plastic zones; \(\:{{u}_{e}}^{{R}_{s}}\) is the displacement at the interface between the plastic zone and the fracture zone, m; \(\:{C}_{0}\) is the initial cohesion, MPa; \(\:{C}_{b}\) is residual cohesion, MPa; \(\:{K}_{C}\) is the softening coefficient of cohesion in plastic zone, MPa; \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{r}}^{{R}_{s}}\) represents the stress boundary condition for the coal body in the borehole when r=\(\:{R}_{s}\); r is the distance of a point in the disturbed coal body from the centre of the borehole, m; βS is the expansion coefficient of the coal body in the plastic zone, and \(\:{\beta\:}_{S}=\frac{1+{sin}\delta\:}{1-\delta\:}\), δ denotes the dilatancy angle of each zone, (°). Based on the above mechanism of unstable collapse boreholes and the analysis of the elastic-plastic distribution of the coal seam, it can provide theoretical support for the filling of coal blocks in the simulation unit of the coal seam around the boreholes in the design of the unstable collapse borehole gas extraction test system below.

Analysis of gas flow resistance in collapsed boreholes

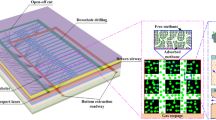

The gas flow within the borehole is a variable mass flow, meaning that as gas continuously enters from the borehole walls, the mass of gas inside the borehole changes over time. In this process, the collapsed coal particles in the collapse borehole further affect the gas flow characteristics. Due to the viscosity of gas, significant pressure losses occur during the flow process, as shown in Fig. 1, which can be attributed to four main factors34: Firstly, the friction-induced along-track resistance loss increases with the change of surface roughness inside the borehole; secondly, the acceleration pressure drop caused by the increase in velocity is also exacerbated by the inflow of gas and the collapse of coal particles; thirdly, the mixing loss formed by the inflow of gas into the borehole wall is affected by the collapsed coal particles, which leads to the uneven flow of the fluids; and lastly, the localised resistance loss caused by the deformation and collapse of the borehole further hinders the smooth flow of gas. The combined effect of these factors reduces the extraction efficiency.

For a collapsed borehole, the collapsed coal particles inside the borehole are the main causes of local resistance loss and frictional resistance loss. The local resistance in a borehole is closely related to the size of the collapsed coal particles. Small coal particles from the collapse tend to fill the voids within the borehole. The smaller the particle size, the smaller the voids, and the larger the specific surface area of the coal particles. The specific surface area refers to the total surface area per unit mass of particles, expressed as:

In the equation, S represents the specific surface area of the coal particles, m2/g; ρ is the density of the coal particles, kg/m3; and a denotes the radius of the coal particles, m.

As particle size decreases, the specific surface area increases, resulting in greater frictional resistance during gas flow. The fine pores created by smaller coal particles further complicate and hinder gas movement, as the gas must navigate around more particles, lengthening the flow path and increasing its complexity and tortuosity. In porous media, gas flow resistance is typically described using Darcy’s Law, expressed by the following equation:

In the equation, Q is the volume flow rate, m3/s; ∆P is the pressure difference, Pa; k is the permeability of porous media ; µ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, Pa·s; L is the length of the flow path, m; H is the flow cross-sectional area, m2. When the flow path increases due to a decrease in coal particle size, an increase in the pressure difference is required to maintain a constant extraction flow rate, indicating an increase in flow resistance.

Design of gas extraction test system for collapsed boreholes

Test system design

The designed simulation system for gas extraction in collapsed boreholes uses carbon dioxide (CO₂) instead of methane (CH4) to ensure safety during experiments. For this test, a CO2 standard gas cylinder with 15 MPa and 40 L of CO2 standard gas was used. The experimental system is shown in Fig. 2. A variable negative pressure extraction pump (capable of providing a constant negative pressure of 25 KPa) is used to provide negative extraction pressure to allow the gas medium in the cylinder to be pumped through the gas extraction borehole simulation unit, thus simulating the flow of gas in the borehole.

The coal seam simulation unit surrounding the extraction borehole consists of two PVC tubes: an outer tube measuring 1.2 m in length with an inner diameter of 240 mm, and an inner tube measuring 1.1 m in length with an inner diameter of 120 mm. The 10 mm holes in the inner tube wall separate the different sizes of coal particles inside and outside for subsequent filling. The distance between the two holes is only 2 mm, which is much smaller than the size of the filled coal particles (5~20 mm), ensuring that the flow of gas is not blocked by the inner tube, thus avoiding any influence on the test results. The gas extraction pipe is a PVC tube with an inner diameter of 90 mm and a length of 700 mm. The holes (8 mm) are distributed on the wall of the tube to prevent the coal particles in the inner tube from entering the borehole and to guarantee the smooth extraction of the gas. The physical diagram of the simulation unit is shown in Fig. 3.

The borehole instability simulation unit consists of a metal filter mesh that is 200 mm in length and 90 mm in outer diameter, designed to fit snugly with the extraction pipe. Different proportions of coal particles are placed in it, and the metal filter mesh equipped with coal particles is sent to the designated position of the extraction pipe to simulate the instability of the borehole. The metal filter prevents coal particles from flowing into the extraction pipe along with the CO2 gas during the experiment, thus avoiding interference with the experiment. The gas extraction parameter monitoring and control unit consists of a flow meter, a CO2 concentration meter, and an electric valve. The flow meter and CO2 concentration meter are used to monitor and record changes in gas concentration and flow rate during the extraction process in different unstable boreholes, while the electric valve allows precise adjustment of the extraction pressure. The final construction of the collapsed and plugged borehole gas extraction test system after connecting all the simulation devices is shown in Fig. 4.

Test scheme

Coal sample selection and coal particle ratio

Based on the sampling site conditions and existing research on post-drilling borehole inspection results35,36, it was found that the collapsed debris inside unstable boreholes generally consists of medium- and small-sized coal blocks. Referring to the size standards for coal blocks outlined in “Division of variety and grading for coal products” (GB/T 17608 − 2022), the experiment selected three different coal particle sizes: medium lump coal (25 ~ 50 mm), small lump coal (15 ~ 25 mm), and granular coal (5 ~ 15 mm).

Coal samples (soft coal) were collected from coal mine site and crushed into different particle sizes. The crushed coal was sieved using 5 mm、10 mm、15 mm、25 mm and 50 mm screens to obtain coal particles that meet the size criteria for medium lump coal, small lump coal, and granular coal. These particles were mixed in different ratios to simulate the collapsed coal within the borehole. A total of 300 g of coal particles was placed in the collapsed section, and the experiment followed the controlled variable method. The coal particles were mixed uniformly with a one-third gradient variation by total weight. The specific mixing ratios are shown in Table 1.

Coal block filling

-

a)

Different coal seam stresses result in varying degrees of coal fracturing around the borehole. To simulate the coal seam conditions surrounding the extraction borehole, coal blocks were placed into the coal seam simulation unit in two zones, ensuring the coal structure closely resembled the fissure state of underground coal seams. As shown in Fig. 5, the three zones surrounding the borehole are, from inner to outer: the caving zone, the crushed zone, and the fractured zone. The collapse zone is simulated by filling the unstable borehole unit with different proportions of collapsed coal particles. In the crushed zone, coal blocks with particle sizes of 10–20 mm are used, while in the fractured zone, coal blocks with particle sizes of 5–10 mm are used.

-

b)

The coal particle filling in borehole instability simulation unit is performed according to the ratio scheme presented in Table 1. After placing borehole instability simulation unit into the extraction pipe, the borehole is sealed. Polyurethane is used as the sealing material between the extraction pipe and the inner and outer PVC glass tubes. The length of the sealing section is set at 100 mm, and a glue gun is used to inject the sealing material. Excluding the 100 mm occupied by the sealing section, the 600 mm extraction pipe is divided into three regions: the bottom collapse zone, the middle collapse zone, and the opening collapse zone, with each region measuring 200 mm in length.

Test steps

-

a)

Place the coal particles, prepared according to the specified ratios, into the borehole instability simulation unit, and insert it into the gas extraction borehole simulation unit.

-

b)

Before starting the experiment, the system’s gas tightness is checked. The CO₂ cylinder is opened, and the solenoid valve is closed to allow gas flow for a period until the concentration reading reaches the specified value. After a period of stabilization, the CO₂ uniformly fill the entire experimental system.

-

c)

Once the solenoid valve is adjusted to the appropriate opening, the variable negative pressure extraction pump is activated to begin the experiment.

-

d)

During the experiment, the concentration and flow readings are monitored, and values for extraction concentration and flow rate are recorded every two seconds. After the extraction process is complete, the total time taken for extraction is noted. Following a period of stabilization, the concentration reading is recorded when it reaches a steady state.

-

e)

After completing one experiment, the collapse position and the ratios of the collapsed coal particles are changed, and the above experimental procedures are repeated.

Test results and analysis

The impact of single-size collapsed coal particle on gas extraction concentration at different collapsed borehole locations

The gas flow in the borehole can change significantly under different collapse conditions, resulting in different degrees of reduction in gas extraction efficiency. The variations in extraction concentration and provide a direct reflection of the coal seam gas extraction performance. Figure 6 shows the variation curves of gas extraction concentration over time for intact borehole and collapsed plugged borehole under negative pressure conditions.

From the analysis of Fig. 6, it can be concluded that gas from the coal seam continuously enters the borehole. During the process of decreasing the coal seam gas concentration from 30 ppm to 20 ppm, the gas extraction concentration in the collapsed plugged boreholes was overall lower than that in the intact boreholes due to the reduction of the effective cross-section of the collapsed section of the boreholes. At the start of gas extraction, the concentration of gas increases sharply under the influence of negative pressure, followed by a gradual decline, resulting in a peak concentration. The observed peak is attributed to the rapid release of gas that had accumulated in the coal seam, a large volume of gas to quickly flow into the borehole, particularly during the initial phase of extraction. The extraction pump draws this gas through the concentration meter at a high concentration, leading to a sudden rise in the readings. The magnitude of the peak extraction concentration in a collapsed plugged borehole reflects the resistive effect of the unstable collapse condition on gas flow. The peak concentration for the intact borehole is 43.12 ppm, which is higher than the peak concentration observed in any collapsed borehole.

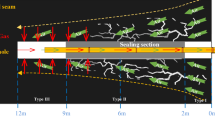

The collapsed coal blocks in collapsed plugged boreholes A, D, and G are of a single grain size, and when the collapsed area occurs at the bottom of the borehole, the peak concentration extraction in collapsed plugged boreholes A, D, and G is 41.86 ppm, 40.38 ppm, and 39.01 ppm, respectively, which shows that the peak concentration extraction is directly proportional to the coal particle size. When the collapse location occurs in the middle or opening of the borehole, the peak extraction concentration overall has a certain reduction relative to the collapse of the bottom of the borehole, but it still shows that it increases with the increase of the collapsed coal block, this is due to the collapsed coal block changes the gas flow channel, the borehole void becomes smaller, and the process of gas flowing through the collapsed coal block is shown in Fig. 7.

The collapsed coal blocks in the three collapsed plugged boreholes are formed by the accumulation of coal particles with different average sizes. The porosity, tortuosity, and characteristic particle size of a porous medium are important factors influencing gas flow. From Eq. (4), it is understood that the permeability k reflects the ability of the porous medium to allow the passage of fluids and is closely related to the particle size. This can be expressed through the Kozeny-Carman37 equation as:

Substituting Eq. (3) gives:

In the equation, k is the permeability; φ is the porosity; τ is the tortuosity; ρ is the density of the coal particles, kg/m3; r is the radius of the coal particles, m; and n is Kozeny’s constant, which is related to the shape of the particles, the distribution of the particle size and other factors.

According to the formula, the finer the coal particles are crushed, the closer the filling between the coal particles will be, and the porosity of the accumulation will decrease. The tortuosity is also closely related to the characteristic particle size. The smaller the particle size is, the more tortuous the gas flow path will be, and the greater the tortuosity will be. Moreover, the smaller the coal blocks are, the larger their specific surface area will be. All these factors lead to a decrease in permeability and an increase in flow resistance, resulting in a lower peak value of the gas extraction concentration. Meanwhile, due to the large specific surface area of small-sized coal particles, the adsorption of gas on their surface is stronger. More gas is adsorbed on the surface of coal particles, which reduces the amount of gas that participates in the flow and is extracted, and further decreases the extraction concentration of gas38,39. Therefore, in the gas extraction test of blocked boreholes, the main factor affecting the flow of extracted gas is the size of the average particle size.

The impact of composite collapsed coal particle on gas extraction concentration at different collapsed borehole locations

In the actual extraction process, the collapsed coal particles will not be only a single particle size. Therefore, in order to explore the more complex variation law of extraction concentration, a more detailed ratio of collapsed coal particles is carried out. As shown in Fig. 8, the trend of the gas extraction concentration in the borehole of the composite collapsed coal particle with the extraction time is roughly the same as that of the single collapsed coal particle borehole. At different collapse positions, the peak concentration of gas extraction still decreases with the decrease of the particle size of the collapsed coal particles, and the larger the proportion of small and medium-sized coal particles in the composite coal particles, the lower the peak concentration of extraction. When the collapse occurs at the borehole opening, the peak extraction concentrations for collapsed boreholes B, C, E, F, H, and I are 38.12 ppm, 37.48 ppm, 37.90 ppm, 37.00 ppm, 36.85 ppm, and 36.55 ppm. The peak concentration of borehole C is lower than that of borehole E, which is due to the fact that borehole C contains one third of granular coal. The collapse borehole F also contains one-third of the granular coal, while the collapse borehole H contains two-thirds of the granular coal, and the peak value of the extraction concentration of the collapse borehole F is higher than that of the collapse borehole H. When the hole and the bottom of the hole collapse, the variation law of the peak value of the extraction concentration is basically the same as that of the orifice. It can be seen that the existence and proportion of small and medium-sized coal blocks in mixed coal particles determine the resistance of gas flow in the collapse borehole. The smaller the particle size of coal block is, the greater the influence on gas extraction concentration is.

The impact of different collapse boreholes on gas flow rate

The total flow rate of gas extraction in boreholes with different collapse conditions is shown in Fig. 9. The coal seam gas concentration decreases from 30 ppm to 20 ppm, the total flow rate for the intact hole gas extraction is 4938.51 mL/min. The extraction flow rates of the collapsed boreholes were all lower than those of the intact boreholes. When the collapsed coal particles are located in the opening, the exit cross-sectional area is greatly reduced, which greatly increases the resistance of gas flow, and the process of gas flow in the borehole is shown in Fig. 10, and the collapse of the borehole usually has a serious negative impact on the whole borehole system, which greatly reduces the extraction flow rate; The total gas extraction flow rate of boreholes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I was 21.74%, 26.28%, 28.79%, 40.54%, 33.81%, 45.50%, 58.81%, 51.53% and 55.28% lower than that of the intact borehole.

When the collapsed coal particles are situated in the middle of the borehole, although the local resistance is larger, the overall flow cross-section is still larger and will not completely block the outlet, the gas needs to bypass the collapsed area, the flow path becomes more complicated and the extraction flow rate is reduced; The total gas extraction flow rate of boreholes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I was 12.26%, 14.24%, 17.03%, 25.21%, 22.78%, 28.80%, 41.99%, 35.35% and 39.71% lower than that of the intact borehole. The bottom collapse increased the local resistance loss in the borehole, but the change in the cross section of the gas flow exit channel was small, and the gas flowed mainly through the channel in the upper part of the borehole, so the overall impact on gas extraction was small, and the extraction concentration and flow rate were closest to those of the intact borehole; The total gas extraction flow rate of boreholes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I was 6.71%, 7.86%, 9.20%, 13.02%, 11.91%, 17.72%, 30.78%, 23.50% and 25.35% lower than that of the intact borehole.

The above analysis shows that the variation laws of gas extraction flow rate and concentration in collapsed boreholes are similar, both decreasing with the decrease in the particle size of collapsed coal particles. When comparing the extraction flow rates of boreholes with the same particle size of collapsed coal particles, the performance is as follows: collapsed bottom of borehole > collapsed middle of borehole > collapsed opening of borehole. In addition, when the borehole opening collapses, the difference in the total extraction flow rate between borehole A and borehole G, which have the largest difference in the particle size of collapsed coal particles, is 1830.74 mL/min, accounting for 37.07% of the extraction flow rate of the intact borehole. When the borehole middle collapses, the difference in the total extraction flow rate between borehole A and borehole G is 1468.05 mL/min, accounting for 29.73% of the extraction flow rate of the intact borehole. When the borehole bottom collapses, the difference in the total extraction flow rate between borehole A and borehole G is 1188.69 mL/min, accounting for 24.07% of the extraction flow rate of the intact borehole. Evidently, the closer the collapse position of the borehole is to the opening, the greater the variation range of the borehole extraction flow rate with the change in the particle size of collapsed coal particles.

The impact of different collapse boreholes on extraction time and residual gas concentration

The gas extraction time of a borehole is one of the key factors influencing the effectiveness of coal seam gas extraction. The efficiency of borehole extraction can be measured by the time required for the initial gas concentration to decrease to a specified level; the shorter the time, the higher the extraction efficiency. Coal seam gas content is a critical parameter for assessing the risk of coal and gas outbursts, as well as the effectiveness of outburst prevention measures. After the extraction process is completed, and the stabilized gas concentration is used to measure the coal seam gas content. The impact of borehole deformation and instability on gas extraction effectiveness is described by considering both the extraction time and coal seam residual gas concentration.

Figure 11 shows the variation in residual gas concentrations in coal seam as the gas extraction concentration decreases from 30 ppm to 20 ppm for both intact and collapsed boreholes. The extraction efficiency of the intact borehole was optimal, residual gas concentration in coal seam of 11.88 ppm. The coal seam residual gas concentration in the collapsed boreholes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I with different collapse locations increased significantly compared with the intact boreholes, and the particle size of the coal particles showed a negative correlation with the coal seam residual gas concentration, i.e., the smaller the particle size of the collapsed coal particles, the higher the coal seam residual gas concentration. In addition, the closer the collapse location is to the opening, the smaller the particle size of the collapsed coal particles is, and the larger the change in the residual gas concentration of the coal seam is, for example, the most obvious increase in borehole G, which increased by 58.84%, 43.77%, and 30.64% for the collapses at the opening, the middle, and the bottom of the borehole, respectively, which indicates that smaller coal particles increase the resistance to the flow of gas, which leads to the retention of gas in the coal seam and in the extraction borehole.

As shown in Fig. 12, the extraction time varied between the collapsed borehole and the intact borehole, with the intact borehole taking a total of 380 s to reach the target extraction concentration. When the collapse occurred at the bottom of the borehole, the extraction time increased with the decrease of the particle size of the collapsed coal particles, which was due to the smaller impact on gas extraction when the collapse occurred at the bottom of the borehole, and the particle size of the collapsed coal particles became a key factor in determining the extraction time of the collapsed borehole.

When the collapse location occurs in the middle of the borehole, the extraction time of boreholes A, B, C, D and E shows that the collapse in the middle of the borehole > collapse at the bottom of the borehole, and the extraction time increased with the decrease of the size of the collapsed coal particles. However, the extraction time of boreholes F, G, H, and I shows that the collapse at the bottom of the borehole > collapse in the middle of the borehole. The reason for this is that, when collapsing in the middle of borehole, the resistance of collapsed coal particles mainly affects the collapsed area and the subsequent boreholes. Therefore, compared with bottom collapse, mid-borehole collapse has a more significant effect on gas extraction. In addition, the particle size of the collapsed coal particles in boreholes F, G, H, and I is relatively small, which significantly reduces the porosity within the borehole, resulting in a narrower gas flow channel. Moreover, the smaller the particle size of the coal particles, the larger their specific surface area. As a result, the contact area between the coal particles and the gas increases, and both the frictional resistance and the surface resistance increase significantly. Under the dual effects of mid-borehole collapse and small-size collapsed coal particles, more gas is retained in the coal seam and the borehole, and less gas enters the gas extraction pipeline. As shown in the observed data, the time for the gas concentration in the pipeline to decrease from 30 ppm to 20 ppm (that is, reaching the target extraction concentration) is shortened. This situation indicates that both the particle size of the collapsed coal particles and the location of the collapse jointly affect the gas extraction time.

When the collapse occurs at the borehole opening, the gas extraction time for the collapsed boreholes A, B, C, D, E, and F, where the proportion of granular coal (5 ~ 15 mm) in the collapsed coal particles is less than two - thirds, is longer than that for the intact borehole. Among them, for boreholes A, B and E, the gas extraction time gradually increases as the particle size of the collapsed coal particles decreases. However, when the particle size of the collapsed coal particles decreases further, for boreholes C, D, F, G, H, and I, the gas extraction time gradually decreases as the particle size of the collapsed coal particles decreases. In particular, when the proportion of granular coal (5 ~ 15 mm) in the collapsed coal particles is more than two - thirds (for boreholes G, H, and I), the extraction time is actually shorter than that of the intact borehole, accounting for 82.11%, 99.47%, and 86.32% of the extraction time of the intact borehole respectively. However, the residual gas concentration in the coal seam is significantly higher than that of the intact borehole and other collapsed boreholes, increasing by 58.84%, 49.16%, and 52.78% respectively compared with that of the intact borehole. The reason for this phenomenon is similar to that of the borehole collapse in the middle of the borehole. The difference lies in that the borehole opening is the main channel for gas to flow out of the coal seam into the gas extraction borehole. Once a collapse occurs at the borehole opening, the gas flow path will be severely obstructed. Compared with the collapse at other parts of the borehole, the collapse at the borehole opening exerts the greatest resistance to gas flow, directly affecting the smoothness of the entire borehole. Therefore, the gas extraction time of the borehole with a collapsed borehole opening varies most significantly with the change in the particle size of the collapsed coal particles. For instance, the gas extraction time of borehole D is the longest, while that of borehole G is the shortest, with a time difference of 176 s between them.

The above analysis shows that during the gas extraction process, when the collapse state of the borehole is too severe, the extracted gas concentration will reach the target extraction concentration in a short period. However, a large amount of gas still remains in the borehole and the coal seam, posing potential safety hazards to the safe operation of coal mines. Judging the gas extraction effect of the borehole solely based on the extraction time cannot be accurate. It is necessary to further determine the effect by combining other extraction parameters such as the residual gas concentration.

Evaluation and delineation of extraction effectiveness of collapsed and plugged boreholes

Based on the above research results findings, both the location of the borehole collapse and the particle size of the collapsed coal jointly influence the gas extraction efficiency of the borehole. In actual coal seam gas extraction operations, the instability conditions of the borehole are often more complex. In order to improve pumping efficiency, it is necessary to classify and study the collapse condition of the borehole. When assessing the extraction efficiency of collapse boreholes, the score for each extraction parameter is determined by calculating the ratio between the extraction parameters of the collapse borehole and the corresponding parameters of the intact borehole, as illustrated in Fig. 13.

For gas extraction boreholes, reaching the target concentration in a shorter time indicates that the design and operation of the gas extraction system are efficient. The residual gas concentration of the coal seam reflects the gas content in the coal seam surrounding the extraction borehole, with lower concentrations indicating higher extraction efficiency. If the extraction time and the residual gas concentration of the coal seam are higher than those of the intact borehole, the score is represented by taking the negative of the ratio between the exceeded value and the corresponding parameter of the intact borehole. Specifically, the higher the extraction time and the residual gas concentration of the coal seam, the lower the score, reflecting the degree of decline in extraction performance. Conversely, when the total flow rate or peak extraction concentration of a collapse borehole is lower than that of the intact borehole, the score should be the positive value of the ratio. The lower the score, the more it reflects a decline in extraction performance. The positive and negative scoring system, based on ratios, provides an intuitive way to quantify the impact of the collapse condition on each extraction parameter, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of changes in gas extraction effectiveness.

During the extraction process, the peak gas extraction concentration, total gas extraction flow rate, extraction time, and the residual gas concentration of the coal seam collectively determine the extraction efficiency of a borehole. The extraction performance scores for collapse boreholes are shown in Fig. 14. As an example, the total extraction flow and peak extraction concentration to intact borehole ratio scores for collapse borehole A, which collapsed in the opening area, are 0.7826 and 0.8910, respectively. The extraction time and the residual gas concentration of the coal seam ratios to the intact borehole are − 0.1211 and − 0.3005, respectively. Summing these four ratios yields an extraction performance score of 1.252 for the A borehole. The same method is applied to evaluate the extraction performance scores of other collapse boreholes.

Based on the extraction performance scores, boreholes with different collapse conditions are classified as follows: a score below 1.0 indicates a Type I collapsed borehole, while a score above 1.0 indicates a Type II collapsed borehole. The collapsed areas of Type I collapsed boreholes in Fig. 14 are mainly concentrated at the borehole opening and middle sections, including boreholes C, D, E, F, G, H, and I that collapsed at the opening and boreholes G and I that collapsed in the middle. Overall, the extraction efficiency of these boreholes is relatively poor, particularly in terms of total gas extraction flow, where all perform below 80% of the intact borehole. Collapses in these two locations create significant obstructions to gas flow, greatly impacting the extraction efficiency of the boreholes.

In the actual gas extraction process, what is most directly observed are extraction parameters such as extraction time and concentration, making it difficult to accurately determine the instability condition of a borehole. Therefore, by evaluating the extraction effectiveness of different unstable collapse boreholes and classifying them into different types, it becomes to identify which boreholes still have good extraction potential and which require repair or adjustment. The approach helps optimize gas extraction strategies and ensures that the extraction efficiency of each borehole is maximized.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The collapse position of the borehole and the particle size of the collapsed coal jointly affect the gas extraction efficiency of the borehole. The smaller the particle size, the lower the porosity and the larger the specific surface area, which leads to an increase in gas flow resistance and an improvement in flow complexity, thus significantly influencing the gas extraction efficiency. Moreover, the closer the position of the borehole collapse is to the borehole opening, the more obvious the influence of the particle size of the collapsed coal particles on the gas extraction efficiency.

-

(2)

The total extraction flow rate and peak concentration of the collapsed borehole decrease as the particle size of the collapsed coal decreases and the position of the borehole collapse gradually approaches the borehole opening, while the residual gas concentration in the coal seam shows the opposite trend. Borehole G with a collapsed borehole opening is most obviously affected by the borehole collapse. Compared with the intact borehole, its peak extraction concentration decreases by 16.4%, the total extraction flow rate decreases by 38.81%, and the residual gas concentration increases by 58.84%.

-

(3)

The gas extraction time is jointly affected by the particle size of the collapsed coal particles and the collapse position. When the collapse occurs at the bottom of the borehole, the gas extraction time prolongs as the particle size of the collapsed coal particles decreases. When the collapse occurs in the middle of the borehole or at the borehole opening, the gas extraction time first increases and then decreases as the particle size decreases. Especially when the borehole opening collapses and the proportion of granular coal (5 ~ 15 mm) exceeds two-thirds (such as boreholes G, H, and I), the gas extraction time is shorter than that of the intact borehole, accounting for 82.11%, 99.47%, and 86.32% of the extraction time of the intact borehole respectively. However, the residual gas concentration in the coal seam is significantly higher than that of the intact borehole and other collapsed boreholes, increasing by 58.84%, 49.16%, and 52.78% respectively compared with that of the intact borehole. This indicates that it is impossible to accurately determine the borehole gas extraction efficiency only based on the gas extraction time.

-

(4)

Based on the extraction performance score, boreholes with a score below 1.0 are classified as Type I collapsed boreholes, while those with a score above 1.0 are classified as Type II. The boreholes classified as Type I in the experiment include the boreholes C, D, E, F, G, H, and I that collapsed at the opening and boreholes G and I that collapsed in the middle. The Type I boreholes exhibited relatively poor overall extraction performance, especially with the total extraction flow rate falling below 80% of the intact borehole.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Szott, W. et al. Numerical studies of improved methane drainage technologies by stimulating coal seams in multi-seam mining layouts. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 108, 157–168 (2018).

Mondal, D. et al. An integrated study on the geochemical, geophysical and Geomechanical characteristics of the organic deposits (Coal and CBM) of Eastern Sohagpur coalfield, India. Gondwana Res. Int. Geosci. J. 96, 122–141 (2021).

Xia, T. et al. A novel in-depth intelligent evaluation approach for the gas drainage effect from point monitoring to surface to volume. Appl. Energy 353(Pt B), 122–147 (2024).

Yuan, L. Research progress of mining response and disaster prevention and control in deep coal mines. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 46 (3), 716–725 (2021).

Yuan, L. Strategic thinking of simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas in deep mining. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 41 (1), 1–6 (2016).

Bao, R. Research and application of concentric ring reinforcement and sealing technology for gas drainage boreholes in soft coal seams. Coal Sci. Technol. 50 (5), 164–170 (2022).

Xie, H. et al. Study on the mechanical properties and mechanical response of coal mining at 1000m or deeper. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 52 (5), 1475–1490 (2018).

Xu, G. et al. Study on regularity of negative pressure and flow rate of gas extraction under borehole deformation and instability. Coal Technol. 42 (07), 92–97 (2023).

Cheng, Y. et al. Effect of negative pressure on coalbed methane extraction and application in the utilization of methane resource. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 42 (6), 1466–1474 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Study and application on influence mechanism of instability and collapse of drainage borehole on gas drainage. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 48 (8), 3102–3115 (2023).

Yao, X., Cheng, G. & Shi, B. Analysis on gas extraction drilling instability and control method of pore-forming in deep surrounding-rock with weak structure. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 35 (12), 2073–2081 (2010).

Li, Z., Tu, M. & Yao, X. Numerical analysis of stability and hole-forming control of gas drainage borehole in deep mine. China Coal. 37 (03), 85–89 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Stability analysis of borehole wall for gas drainage boreholes in broken soft coal seam. Saf. Coal Mines. 49 (08), 189–193 (2018).

Zhai, C. et al. Analysis on borehole instability and control method of pore- forming of hydraulic fracturing in soft coal seam. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 37 (09), 1431–1436 (2012).

Guo, M., Shuang, H. & Liu, S. Experimental study on deformation and failure characteristics of drainage boreholes based on speckle monitoring. Saf. Coal Mines. 54 (7), 130–136 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Research status of borehole instability characteristics and control technology for gas extraction in soft coal seam. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 49 (3), 131–135 (2022).

Han, Y. et al. Numerical simulation of instability and failure types of coalbed borehole based on Hoek-Brown criterion. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 45 (S1), 308–318 (2020).

Li, S., Sun, Y., Wang, Y. & Liu, C. Analysis of the stability of the gas extraction boreholes based on the Hoke-Brown criterion and their sealing-up methods. J. Saf. Environ. 16 (3), 135–139 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Influence of deformation and instability of borehole on gas extraction in deep mining soft coal seam. Adv. Civ. Eng. (2021). 2021(Pt.7).

He, S., Ou, S. & Lu, Y. Failure mechanism of methane drainage borehole in soft coal seams: insights from simulation, theoretical analysis and in-borehole imaging. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 168, 410–421 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Research on testing technology of deformation and failure of bore-holes in coal seam gas drainage and its application. Coal Sci. Technol. 48 (10), 37–44 (2020).

Ruan, K. & Fu, X. A modified Kozeny-Carman equation for predicting saturated hydraulic conductivity of compacted bentonite in confined condition. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14 (3), 984–993 (2022).

Yin, P. et al. The modification of the Kozeny-Carman equation through the lattice Boltzmann simulation and experimental verification. J. Hydrol. 609, 127738 (2022).

Schulz, R. et al. Beyond Kozeny-Carman: predicting the permeability in porous media. Transp. Porous Media. 130 (2), 487–512 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Analytical model for fracture conductivity with multiple particle sizes and creep deformation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 102, (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Analytical model for fracture conductivity considering rod proppant in pulse fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 217, (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Effect of mass loss on pore permeability in gravel aquifers. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 47 (6), 2360–2368 (2022).

Pang, M., Zhang, T., Meng, Y. & Ling, Z. Experimental study on the permeability of crushed coal medium based on the Ergun equation. Sci. Rep. 11, 23030 (2021).

Ma, D. et al. Grain size distribution effect on the hydraulic properties of disintegrated coal mixtures. Energies 10 (5), 612 (2017).

Han, Y. & Zhang, F. Progress in research on instability mechanism of coalbed borehole. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 10 (04), 114–119 (2014).

Wang, Z., Liang, Y. & Jin, H. Analysis of mechanics conditions for instability of outburst-preventing borehole. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 25 (04), 444–448 (2008).

Cheng, H. & Qiao, Y. Study on hydraulic fractured gas drainage effect based on Hoek-Brown criterion. Coal Sci. Technol. 46 (9), 111–116 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. Deformation and failure characteristics of gas drainage drilling-reaming coal mass in non-uniform stress field. J. Chin. Coal Soc. 48 (4), 1538–1550 (2023).

Li, X. & Wang, K. Theoretical research on negative pressure distribution law of long coal seam hole. Coal Technol. 34 (02), 140–143 (2015).

Xiao, P. et al. Deformation and collapse patterns of gas drainage boreholes and a precise monitoring technology. Coal Geol. Explor. 52 (3), 14–23 (2024).

Sun, S. et al. The deformation characteristics of surrounding rock of crossing roadway in multiple seams under repeated mining and its repair and reinforcement technology. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 37 (4), 681–688 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. A new method for predicting permeability based on modified Kozeny-Carmen equation. J. Jilin Univ. Earth Sci. Ed. 47 (3), 899–906 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. The effect of analytical particle size on gas adsorption porosimetry of shale. Int. J. Coal Geol. 138, 103–112 (2015).

Vallejos-Burgos, F. et al. 3D nanostructure prediction of porous carbons via gas adsorption. Carbon 215, (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the following funds: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (52104215), the Research Fund of The State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, CUMT (SKLCRSM23KF003) and Key Laboratory Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (24JS030). The authors are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52104215), the Research Fund of The State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, CUMT (SKLCRSM23KF003) and Key Laboratory Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (24JS030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L., writing—original draft; S.S., supervision; S.H., conceptualization; J.C., methodology; Y.X., validation; X.C. and R.B., data collation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, S., Liu, G., He, S. et al. Study on the gas flow resistance state in unstable collapse boreholes and the classification of borehole types. Sci Rep 15, 14433 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99387-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99387-w