Abstract

This paper proposed a delayed fractional-order SEIHR-M model incorporating media influence to investigate the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Malaysia. By integrating fractional-order dynamics and time-delay media influence into a unified epidemic framework, this novel structure more accurately captures both memory effects and behavioral response lags in the context of COVID-19. Theoretical analysis verified the existence, non-negativity, and boundedness of the solutions, ensuring the biological feasibility of the model. The basic reproduction number \(R_0\) was derived using the next-generation matrix method, serving as a key metric for evaluating disease transmission and model stability. Furthermore, when \(R_0 < 1\), the disease-free equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable regardless of the value of the delay parameter \(\tau\). When \(R_0 > 1\), the stability of the endemic equilibrium exhibits two scenarios: if \(\tau = 0\), sufficient conditions for local asymptotic stability are provided; if \(\tau > 0\), there exists a critical delay \(\tau _0\). The endemic equilibrium remains locally asymptotically stable for \(0< \tau < \tau _0\) but becomes unstable for \(\tau > \tau _0\), undergoing a Hopf bifurcation at \(\tau = \tau _0\), leading to periodic oscillations. The numerical simulation results not only validate the theoretical analysis but also show that as the fractional-order parameter increases, the system exhibits more pronounced oscillations; furthermore, longer delay times facilitate the emergence of these oscillatory behaviors, making the epidemic more prone to recurrent and periodic fluctuations. By fitting the model with early COVID-19 data from Malaysia, the feasibility and applicability of the model are further validated, and the superior fitting performance of the fractional-order delay model compared to the corresponding integer-order model is highlighted. Finally, sensitivity analysis results show that media interventions have a significant impact on epidemic spread, further demonstrating that timely and effective information dissemination plays a crucial role in reducing the peak of infections and controlling the epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has brought infectious diseases back into focus, becoming one of the most pressing public health crises in recent years. Over the span of three years, the cumulative number of COVID-19 infections has reached billions, with global deaths exceeding millions, resulting in unprecedented impacts on the global economy and human health1,2. In Malaysia, the effects of the pandemic have been particularly profound. In the early stages of the outbreak, the Malaysian government implemented strict Movement Control Orders (MCO)3, including nationwide lockdowns and social distancing measures, to curb the spread of the virus. While these measures initially succeeded in reducing infection rates, they caused significant disruptions to economic activities and social life. Tourism, one of Malaysia’s key industries, was hit particularly hard, with international tourist arrivals plummeting, leaving related businesses and workers struggling to survive4,5.

Faced with the challenges posed by infectious diseases, establishing appropriate mathematical models for theoretical and quantitative analysis of epidemic dynamics has become increasingly important. In the early 20th century, Kermack and McKendrick, based on their study of the Black Death, proposed the classic SIR model6. This model defined three key groups: Susceptible (\(S\)), Infectious (\(I\)), and Recovered (\(R\)), assuming that recovered individuals do not become reinfected. This model laid the foundation for infectious disease modeling. Subsequently, they introduced the SIS model7, which allowed recovered individuals to become reinfected and incorporated the “threshold theory,” providing a classic criterion for determining whether an infectious disease would spread widely.

Over the past few decades, the foundational SIR framework and its variants have played a pivotal role in epidemiological modeling. In light of the complex, multi-stage nature of COVID-19, researchers from various disciplines have substantially expanded these classic models-resulting in compartmental structures such as SEIR, SEIHR, SEIQR, SVIR, SVEIR, and SEIRV8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. By incorporating additional compartments and parameters (e.g., incubation periods, hospitalization, quarantine, and vaccination), these refined frameworks capture the intricate biological, behavioral, and social dimensions of disease transmission. This cross-disciplinary approach not only yields a more accurate and nuanced depiction of epidemic dynamics but also provides valuable theoretical support for public health decision-making18,19,20,21.

Despite this, classical integer-order epidemic models have laid an important foundation for understanding the spread of infectious diseases. Nevertheless, they assume that the disease transmission process is instantaneous and memoryless, which presents limitations in describing the complex dynamic characteristics of actual biological systems. To address these shortcomings, researchers have introduced fractional calculus and developed fractional-order epidemic models. Fractional-order differential equations (FODEs), as a significant branch of fractional calculus, have gained widespread attention due to their ability to effectively characterize memory effects and hereditary properties. Existing studies have achieved significant results regarding the local existence, uniqueness, and structural stability of solutions to certain fractional-order differential equations22,23. These theoretical advancements in fractional-order differential equations have paved the way for their practical application in modeling complex systems, including epidemic dynamics. Building on this foundation, Rezapour et al.24 developed a fractional-order SEIR model using the Caputo fractional derivative to study COVID-19 dynamics. Their analysis demonstrated the stability and uniqueness of solutions using fixed-point theory, with numerical simulations validating the model’s predictions in Iran and globally. Aba Oud et al.25 developed a fractional-order mathematical model for COVID-19 dynamics using the Caputo fractional derivative, incorporating quarantine, isolation, and environmental viral load. Numerical simulations based on real data from Pakistan validated the model, highlighting its ability to capture memory effects and the disease’s dynamics. Batiha et al.26 proposed fractional-order extensions of the SEIR model based on Caputo and Caputo-Fabrizio operators, highlighting the role of fractional calculus in capturing memory effects in disease dynamics. Expanding upon these findings, several other studies27,28,29,30,31,32 further demonstrated how fractional-order extensions effectively capture memory effects and complex dynamics in disease transmission.

During the pandemic, media reporting has played a critical role as a key channel for information dissemination, guiding public behavioral changes and promoting the implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). By rapidly spreading pandemic-related information, it effectively reduced individual infection risks and influenced the spread of the disease as well as the effectiveness of public health interventions33,34. Media coverage has emerged as a critical factor in mitigating COVID-19 transmission by shaping public behavior and informing intervention strategies. Mohsen et al.35 developed a COVID-19 model incorporating quarantine strategies and media coverage, dividing the population into five compartments. They proved the model’s stability, with \(R_0 < 1\) ensuring a stable disease-free equilibrium, and verified global stability via the Lyapunov function. The study highlighted the critical role of media in reducing disease spread. Furthermore, Akdim et al.36 developed a fractional-order epidemic model incorporating media coverage and captured long-term memory effects using the Caputo fractional derivative. Numerical simulations revealed that while long-term memory had limited impact on stability, increasing media awareness significantly reduced the number of infected individuals and the epidemic peak.

However, media reporting does not have an immediate effect; there is a delay in the process from information release to public reception and subsequent behavioral response. This delay, or time lag, is a common phenomenon in biology, especially in the transmission of infectious diseases, such as the incubation period, the infection period, the immune period of recovered individuals, and the dissemination of media reports. Time lags not only more accurately reflect the intrinsic mechanisms of disease transmission but also have profound impacts on the dynamical behavior of systems, potentially destabilizing them and inducing complex dynamics such as periodic oscillations, bifurcations, or chaos37,38. Agaba and Soomiyol39 developed an SEIRM time-delay model to study COVID-19 transmission, emphasizing awareness. They found that \(R_0 < 1\) ensures asymptotic stability of the disease-free state, while \(R_0 > 1\) leads to an endemic state, potentially undergoing Hopf bifurcation under certain delays. Liu et al.40 proposed a time-delayed SAIM model to evaluate the effects of vaccination and media coverage on COVID-19 control. Their model incorporates delays reflecting vaccination willingness influenced by media, and their analysis revealed stable equilibria and periodic solutions under various parameter conditions. Therefore, incorporating time delays into models provides critical insights into the interplay between information dissemination and disease dynamics, offering valuable theoretical foundations for refining epidemic control strategies.

Although fractional-order epidemic models have gained widespread attention for their ability to capture memory effects and nonlocal characteristics, few studies have incorporated media reporting with time delays into such models. Media reporting itself exhibits memory-driven characteristics, making it highly compatible with the fractional-order framework. Addressing this research gap, this paper proposes a Caputo fractional-order SEIHR-M model to describe the early spread of COVID-19 in Malaysia. The model uniquely incorporates a media module with a delay term to simulate the lag between media reporting and public behavioral responses. By combining fractional-order dynamics with time-delay mechanisms, this study provides a novel perspective for understanding and predicting the interplay between media reporting and disease transmission. The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

We constructs a delayed SEIHR-M model based on Caputo fractional derivatives, consisting of six core compartments: Susceptible (S), Exposed (E), Infected (I), Hospitalized (H), Recovered (R), and Media (M). The fractional derivatives capture the memory effect and nonlocal characteristics of disease transmission, while the delay term simulates the lag between media reporting and public behavioral responses.

-

2.

Through theoretical analysis, this paper demonstrates the existence, non-negativity, and boundedness of the model solutions, ensuring biological and mathematical feasibility. Additionally, the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) is derived as a critical metric for evaluating the epidemic’s potential. The existence and stability of both disease-free and endemic equilibrium points are analyzed. Furthermore, Hopf bifurcation conditions are explored to understand potential periodic dynamics in the system.

-

3.

Through numerical simulations, the derived theorems are validated, and the model is simultaneously analyzed under different fractional orders and delay parameters. The results reveal the evolution of epidemic trends and the sensitivity of the system to key parameters. Beyond that, the simulations validate the conditions for Hopf bifurcation and demonstrate the significant impact of the delay parameter \(\tau\) on the system’s dynamic behavior, including the potential emergence of periodic oscillations.

-

4.

Using early COVID-19 data from Malaysia, the model parameters were estimated using the Product-Integration method and nonlinear least squares optimization. Error analysis and local sensitivity analysis further demonstrated the model’s reliability and applicability, while emphasizing the significant role of media interventions in controlling the epidemic.

Preliminaries

Definition 1

41 Let \(\alpha\) be a positive real number, let \(n - 1 \le \alpha < n\), where \(n\) is a positive integer. For a function \(f(t)\) defined on the interval \([a, b]\), the Caputo fractional derivative of order \(\alpha\) of \(f(t)\) is defined as

For the function \(f(t)\), its \(\alpha\)-order Caputo fractional derivative, where \(t \in [a, b]\), and \(\Gamma (z)\) represents the Gamma function.

Lemma 1

42 Consider the following fractional differential system with time delay and initial conditions

where the function \(f\) is continuous in a neighborhood of the point \((t_0, \varphi (t_0), x(t_0 - \tau ))\). If \(f\) satisfies the Lipschitz condition with respect to all variables except \(t\), and the initial function \(\varphi _k(t) \in [t_0 - h, t_0]\), then there exists a unique continuous solution to the system on \(t_0 \le t \le t_0 + h\), where \(h\) is sufficiently small.

Lemma 2

43 Routh–Hurwitz Criterion: Consider the characteristic equation

where the determinants are defined as:

All roots have negative real parts if and only if \(\Delta _k > 0\) for \(k = 1, 2, \dots , n\).

Lemma 3

44 Consider the following nonlinear delay fractional differential equation with a Caputo fractional derivative:

where \(\alpha \in (0,1]\), \(X(t) \in \mathbb {R}^n\), \(\tau > 0\). The characteristic equation of system (1) is given by:

Here, \(A\) and \(B\) correspond to the Jacobian matrices at the equilibrium points of \(f(X(t))\) and \(g(X(t-\tau ))\) in system (1). If all the characteristic roots of the characteristic equation satisfy the condition \(-\pi < \arg (s) \le \pi\) and have negative real parts, the zero solution of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable.

Lemma 4

45 For a delayed \(n\)-dimensional fractional-order system:

if the following conditions are satisfied, the system will undergo a Hopf bifurcation at \(\tau = \tau _0\):

-

(i)

The eigenvalues \(\lambda\) of the Jacobian matrix of the linearized system (2) satisfy \(|\arg (\lambda )| > \alpha \pi / 2\);

-

(ii)

The characteristic equation of system (2) has a pair of purely imaginary roots at \(\tau = \tau _0\);

-

(iii)

The eigenvalues \(s(\tau )\) of the Jacobian matrix of the linearized system satisfy the transversality condition:

$$\frac{d\Re [s(\tau )]}{d\tau }\bigg |_{\tau = \tau _0} > 0.$$

Model formulation

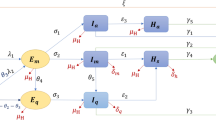

We consider developing a time-delay epidemic model based on the Caputo fractional derivative, incorporating media coverage to describe the dynamics among Susceptible \((S),\) Exposed (\(E\)), Infectious (\(I\)), Hospitalized \((H),\) and Recovered (\(R\)) individuals. The time-delay term in the model is primarily used to describe the response delay of media coverage, reflecting the time lag between the dissemination of external information and its actual impact on population behavior. Additionally, the media compartment \(M(t)\) focuses on active cases \(I(t - \tau )\) at a specific time as the basis for regulating information interventions. Specifically, the dynamics of the model are as follows:

where

we have

Subject to the initial conditions:

where \(S_0, E_0, I_0, H_0, R_0, M_0\) are all non-negative. The Left-Caputo fractional derivative is denoted by \(^C D^\alpha,\) where \(\alpha\) is the fractional derivatives’ order and \(\alpha \in (0, 1]\). We balance the time dimension in the model (3).

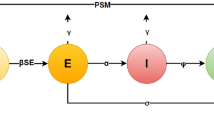

Figure 1 clearly illustrates that model (3) captures the dynamic process of COVID-19 under the influence of media coverage. Specifically, when susceptible individuals \(S(t)\) come into contact with infectious individuals, a portion of them transitions from \(S\) to \(E\), indicating that they have entered the latent phase without showing symptoms. Subsequently, individuals in the exposed compartment \(E(t)\) convert to infectious individuals \(I(t)\) at a certain rate, thereby acquiring the ability to transmit the virus. If the condition of an infectious individual \(I(t)\) deteriorates, they move into the hospitalized compartment \(H(t)\) or, with a certain probability, directly recover into \(R(t)\); hospitalized patients \(H(t)\) may eventually recover and transition to \(R(t)\). Moreover, due to the absence of effective treatments, both infectious \(I(t)\) and hospitalized \(H(t)\) individuals face a non-negligible risk of death. In addition, the media coverage \(M(t)\) fluctuates with the current number of infections and functions to suppress the epidemic spread by reducing contact rates.

The flow diagram of the model (3) with media influence..

In most epidemic models incorporating media coverage, \(M(t)\) is used to quantify the intensity of media reporting and the level of public attention to epidemic information. Specifically, when the number of infections increases, the volume of media reports and the public’s attention generally rise accordingly, resulting in a higher value of \(M(t)\)46,47,48. This increase reflects a positive feedback mechanism from the epidemic scale to the media response. In our model, this effect is incorporated into the transmission term via the function

where \(\beta _1^\alpha\) represents the baseline transmission rate in the absence of media intervention, \(\beta _2^\alpha\) represents the reduction in effective exposure to the epidemic due to media coverage, and \(m\) is a saturation parameter that prevents the suppressive effect from increasing without bound. Since media coverage cannot completely block disease transmission, we assume that \(\beta _1^\alpha > \beta _2^\alpha\), indicating that even at maximum media intervention, a residual transmission rate remains. So, we introduce \(\beta _{\textrm{eff}}(M)\), to capture the regulatory effect of media coverage on the infection rate. When there is no media intervention, this function reverts to the baseline transmission rate \(\beta _1^\alpha\). However, as the media coverage grows stronger, the actual transmission rate is reduced to a lower level, thereby reflecting the impact of public protective measures prompted by the disseminated information. Moreover, the media compartment \(M(t)\) is modeled as an independent dynamic variable whose evolution is described by

where \(\sigma _1^\alpha\) represents the follow-up rate of media information coverage (with a time delay \(\tau\) that captures the lag between the dissemination of media coverage and the subsequent adoption of protective measures by the public ), and \(\sigma _2^\alpha\) denotes the dissipation rate of media information coverage. By treating media coverage as an independent compartment, the model can more clearly depict how the scale of the epidemic drives the level of media attention and how the media, in turn, regulates the transmission rate via a feedback mechanism. Table 1 summarizes the biological interpretations of the compartments and parameters.

Analysis of delayed fractional-order model

This section provides a theoretical analysis of the delayed fractional-order epidemic model. First, we study the existence and uniqueness of solutions and verify their positivity and boundedness. Next, we analyze the existence of equilibrium points, including the disease-free and endemic equilibria, to reveal the long-term behavior of the system. Furthermore, we derive the expression for the basic reproduction number (\(R_0\)), a key threshold parameter used to determine whether the disease will die out or persist. Finally, we analyze the stability of the equilibrium points, focusing on the stability conditions of the disease-free and endemic equilibria, and explore the conditions under which Hopf bifurcation occurs, providing a theoretical basis for the potential oscillatory dynamics of the system.

Existence, non-negativity and boundedness of solutions

Theorem 1

For any positive initial condition

there always exists a non-negative, bounded, and unique solution

for model (3), and it remains in \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\), where

the closed set \(\Gamma\) is the positive invariant of model (3).

Proof of Theorem 1

To demonstrate the non-negativity of the solutions, we consider the corresponding variables in model (3), Specifically, from the equations of the model (3), we have:

By using Theorem 2.149, the non-negativity of the solutions is guaranteed since each derivative term is non-negative when the corresponding variable is zero. Moreover, because all compartments have non-negative initial conditions and their fractional derivatives cannot become negative, these variables will never drop below zero throughout the course of the epidemic. Hence, we have \(X(t) = (S(t), E(t), I(t), H(t), R(t), M(t))\ge 0\) for any \(t \ge 0\).

To show that all the state variables remain bounded for all \(t \ge 0\), we first consider the total population \(N(t) = S(t) + E(t) + I(t) + H(t) + R(t)\) and derive an upper bound using a fractional Grönwall-type inequality. Afterwards, we demonstrate that M(t) is also bounded by leveraging the boundedness of I(t). Such boundedness guarantees that the model solutions are biologically feasible, preventing unrealistic blow-up of compartment populations or media coverage. First, we sum all equations in model (3) to obtain:

The inequality can be obtained:

Since \(I\ge 0, H\ge 0\), we obtain:

and from the lemma 3.350, we get:

Rearranging the terms yields

If we take the limit as \(t \rightarrow \infty\), \(N \rightarrow \frac{\Lambda ^{\alpha }}{d^{\alpha }}\). Hence, we have:

Next, consider \(M(t)\)

Given the boundedness of \(N(t)\), we have \(I(t) \le N(t)\), which implies:

Substituting the upper bound of \(I(t - \tau )\) into the equation for \(M(t)\), we obtain:

Thus, we find:

Considering the initial condition \(M(0)\), we conclude that \(M(t)\) is bounded as

This shows that the solution is bounded and it remains in \(\mathbb {R}_+^6\), where

the closed set \(\Gamma\) is the positive invariant of model (3).

To establish that model (3) has a unique solution for any given non-negative initial condition, we will show that the right-hand side of model (3) is Lipschitz continuous in set \(\Gamma\), which then implies local existence and uniqueness via the Banach fixed-point principle51. Specifically, we define the functions based on the system equations and confirm that there exists a constant \(L > 0\) such that

for any two points \(Z\) and \(Y\) in a bounded domain. Consider the time interval \([t_0, t_0 + h]\), where h is sufficiently small, and the bounded domain

we have:

where \(t_1\) and \(U\) are finite positive constants. Let

be two points in \(\Gamma\). Define the mapping \(G : \Gamma \rightarrow \mathbb {R}_+^6\) such that

We show that

Then, we calculate \(G(Y) - G(Z)\) for each component:

we get:

where

Thus, \(G(X)\) satisfy the Lipschitz condition. By combining with Lemma 1, it follows that model (3) with the given initial value condition has a unique solution. Therefore, combining the boundedness and non-negativity results, we have established that model (3) admits a unique solution that remains in \(\Gamma\) for all \(t \ge 0\). This completes the proof of Theorem 1. \(\square\)

Basic reproduction number

The basic reproduction number \(R_0\) is a key metric for quantifying the transmission potential of an infectious disease. It is defined as the average number of secondary infections caused by a single infected individual during their infectious period in a completely susceptible population. \(R_0\) serves as a critical threshold for determining whether a disease will spread within a population. Typically, if \(R_0 < 1\), the disease will eventually die out; if \(R_0 > 1\), the disease is likely to persist and spread, indicating the need for intervention measures to control its transmission.

In this section, we calculate \(R_0\) using the next-generation matrix method52. This method is also applicable to fractional-order epidemic models53,54. This approach constructs two key matrices, \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\), to reformulate the dynamics of disease transmission into a mathematically tractable form. The matrix \(\Phi\) represents the transmission rates from infected individuals to new infections, while the matrix \(\Psi\) captures the transition rates of infected individuals between various states. By determining the spectral radius of these matrices, we derive the specific expression for \(R_0\). Based on the analysis of model (3), the specific forms of the matrices \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\) are presented as follows

The inverse of \(\Psi\), denoted by \(\Psi ^{-1}\), is given by

then, we have

The basic reproduction number of model (3) is mathematically expressed as follows

where \(\rho (*)\) denotes the spectral radius of a matrix \(*\).

Existence of equilibrium points

Equilibrium points represent the stable states that the system may reach over time, including the disease-free equilibrium and the endemic equilibrium. The disease-free equilibrium corresponds to a state where the disease is completely eradicated, while the endemic equilibrium indicates a state where the disease persists in the population at a stable level. By studying these equilibria, we can gain a deeper understanding of the conditions under which the disease spreads and the long-term behavior of the system. In this section, we discuss the existence of the disease-free equilibrium and the endemic equilibrium.

Theorem 2

For model (3), a disease-free equilibrium \(E_0 = \left( \frac{\Lambda ^{\alpha }}{d^{\alpha }}, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0\right)\) always exists. Furthermore, if \(R_0 > 1\), model (3) has a unique endemic equilibrium \(E^* = (S^*, E^*, I^*, H^*, R^*, M^*).\)

Proof of Theorem 2

Let the left side of model (3) equal to zero, we can obtain the following algebraic equation

A simple calculation shows that in Eq. (5) there always exists a disease-free equilibrium \(E_0 = \left( \frac{\Lambda ^{\alpha }}{d^{\alpha }}, 0, 0, 0, 0\right).\) Assuming that there exists a positive solution \(X^* = (S^*, E^*, I^*, H^*, R^*, M^*)\) to Eq. (5), by Eq. (5) we can express \(S^*, E^*, H^*, R^*\) and \(M^*\) in terms of \(I^*\), respectively, with the following expression:

By substituting the expressions of \(S^*\), \(E^*\), \(H^*\), \(R^*\), and \(M^*\), which are expressed in terms of \(I^*\), into the first equation of Eq. (5), we obtain the following expression:

To simplify the above equation, we group the terms by their powers of \(I^*\). The quadratic term, linear term, and constant term are represented as coefficients \(a_1\), \(a_2\), and \(a_3\), respectively. This allows us to rewrite the equation in the standard quadratic form:

where the coefficients \(a_1\), \(a_2\), and \(a_3\) are defined as follows:

Clearly, \(a_1\) is always negative. When \(R_0 < 1\), it follows that \(a_2 < 0\) and \(a_3 < 0\). According to Descartes’ rule of signs55, this implies that the equation does not have any positive real roots when \(R_0 < 1\). When \(R_0 > 1,\) then \(a_3 > 0\). it is necessary to further distinguish the signs of \(a_2\). In one scenario, where \(a_2 < 0\), the negative \(a_2\) combined with a positive \(a_3\) results in exactly one sign change in the sequence of the polynomial coefficients; thus, by Descartes’ rule of signs, there is precisely one positive real root. Alternatively, if \(a_2 > 0\) , the coefficient sequence still exhibits exactly one sign change, leading again to the conclusion that the polynomial has exactly one positive real root. Therefore, when \(R_0 > 1\), model (3) admits a unique endemic equilibrium \(E^* = (S^*, E^*, I^*, H^*, R^*)\). \(\square\)

Stability of the disease-free equilibrium

Theorem 3

The disease-free equilibrium point \(E_0\) of model (3) is locally asymptotically stable if the conditions \(R_0 < 1\) is satisfied.

Proof of Theorem 3

At the disease-free equilibrium \(E_0\), the Jacobian matrix \(J_{E_0}\) is given by

The corresponding characteristic equation is given by \(\det (\lambda E - J(E_0)) = 0\), where \(E\) is the identity matrix. Therefore, we obtain:

Clearly, \(\lambda _1 = -d^{\alpha }\), \(\lambda _2 = -(d^{\alpha } + \delta _2^{\alpha } + \xi _2^{\alpha })\) , \(\lambda _3 = -d^{\alpha }\) and \(\lambda _4 = -\sigma _2^{\alpha }\) are four eigenvalues of the matrix \(J_{E_0}.\)

The remaining eigenvalues \(\lambda _5\) and \(\lambda _6\) are the roots of the following equation:

where

To determine the stability of the equilibrium, consider the condition \(R_0 < 1\). In this case, it can be shown that \(c_2 > 0\). By applying the Routh–Hurwitz conditions for fractional-order differential equations56, the eigenvalues satisfy \(|\text {arg}(\lambda _i)| > \frac{\alpha \pi }{2}\) for \(i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\). Therefore, the stability conditions are satisfied, and the disease-free equilibrium \(E_0\) is locally asymptotically stable for any \(\alpha \in (0, 1]\), provided that \(R_0 < 1\). \(\square\)

Stability of the endemic disease equilibrium

Stability of the endemic disease equilibrium for \(\tau = 0\)

Theorem 4

If \(R_0 > 1\) and \(\tau = 0\), the endemic equilibrium \(E^* = (S^*, E^*, I^*, H^*, R^*, M^*)\) of the model (3) is locally asymptotically stable, provided the following conditions are satisfied:

where

Proof of Theorem 4

At the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\), the Jacobian matrix \(J_{E*}\) of model (3) is given by:

From the structure of the matrix \(J_{E^*}\), the following eigenvalues can be directly identified:

These eigenvalues are both negative. To analyze the remaining eigenvalues, we remove the rows and columns associated with \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\). The reduced Jacobian matrix is:

The characteristic equation is

where

From Lemma 2, we can say that the endemic disease equilibrium \(E^* = (S^*, E^*, I^*, H^*, R^*, M^*)\) is locally asymptotically stable, provided the following conditions are satisfied:

\(\square\)

Stability of the endemic disease equilibrium for \(\tau > 0\) and Hopf bifurcation

Theorem 5

This theorem holds if the following conditions are satisfied:

where

Under these conditions, when \(R_0 > 1\), there exists a bifurcation parameter \(\tau _0\). Specifically:

-

(ii)

If \(\tau < \tau _0\), the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\) is locally asymptotically stable;

-

(i)

If \(\tau > \tau _0\), the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\) becomes unstable;

-

(iii)

At \(\tau = \tau _0\), a Hopf bifurcation occurs at \(E^*\).

The bifurcation parameter \(\tau _0\) is given by:

Proof of Theorem 5

When \(\tau > 0\), the Jacobian matrix of model (3) at the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\) is given by:

The characteristic equation of model (3) is given by:

It is evident that the eigenvalues include \(\lambda _1 = -d^\alpha\) and \(\lambda _2 = -(\xi _2^\alpha + \delta _2^\alpha + d^\alpha )\). Thus, the remaining eigenvalues satisfy the following equation:

where

To demonstrate that model (3) undergoes a Hopf bifurcation at the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\), it is necessary to show that Eq. (6) has a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues. Substituting the eigenvalue \(\lambda = \omega i, (\omega > 0)\) into Eq. (6), we have:

Then, separating the real and imaginary parts, we obtain:

It follows that:

By eliminating \(\tau\) from the system of equations (8)

Let \(z = \omega ^2\)

where

Let \(k_4 < 0\), then \(b_4^2 < (q p \varepsilon ^{\alpha } \sigma _1^{\alpha })^2\), and thus \(g(0) < 0\) and \(g(+\infty ) \rightarrow +\infty\). Therefore, Eq. (11) has at least one positive root. Define \(\sqrt{z_0} = \omega _0\), then Eq. (11) has a pair of purely imaginary roots \(\pm \omega _0 i\).

Returning to the bifurcation analysis, let \(\tau\) be a parameter and consider Eq. (11) as a function of \(\tau.\) Define \(\lambda (\tau ) = \eta (\tau ) + \omega (\tau )i\) as the eigenvalue of Eq. (11). Suppose the initial parameter value \(\tau _0\) satisfies \(\eta (\tau _0) = 0, \omega (\tau _0) = \omega _0\), and \(\omega _0 > 0\). To establish the existence of a Hopf bifurcation, it is necessary to verify the sign of \(\frac{d\text {Re}(\lambda (\tau ))}{d\tau }\big |_{\tau =\tau _0}\).

For Eq. (6), differentiating with respect to \(\tau\), we have:

After rearrangement, we get:

Therefore,

So

According to the rules of complex division:

Consequently,

From Lemma 4, it follows that the theorem can be proven if the sign of the expression

is greater than zero. \(\square\)

Numerical simulation

This section presents numerical simulations to validate the theorems in last section. The numerical simulations are conducted using an explicit rectangular Product-Integration (PI) scheme57, suitably modified to solve fractional-order differential equations with a constant delay. By setting a series of initial parameter values and compartment conditions, the stability of the model compartments under the condition \(R_0 < 1\) is simulated. Additionally, the model’s behavior is compared under different fractional orders when \(\tau = 0\) and \(\tau \ne 0\). Furthermore, the relationship between fractional orders and the basic reproduction number is analyzed under the condition \(R_0 < 1\). Additionally, the impact of different \(\tau\) values on the dynamics of compartments under the same fractional order is simulated. By varying parameter values, the stability of the model under different fractional orders for \(R_0 > 1\) is investigated. The influence of different \(\tau\) values on the dynamics of compartments is also analyzed. When \(R_0 > 1\) and \(\tau > \tau _0\), the occurrence of periodic behavior in the model is also simulated. Moreover, the relationship between fractional orders and the basic reproduction number is further explored. By constructing three-dimensional images, the stability of compartments under \(R_0 > 1\) is further analyzed based on different \(\tau\) values. Finally, the relationship between fractional orders and \(\tau\) is discussed, specifically focusing on the variation of \(\tau _0\) values that lead to periodic behavior under different fractional orders. The hardware and software environment for the numerical simulations is presented in Table 2.

Condition 1. The following initial parameter values were used: \(\Lambda = 5\), \(\beta _1 = 0.02\), \(\beta _2 = 0.01\), \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.00002\), \(\xi _2 = 0.00001\), \(\delta _1 = 0.1\), \(\delta _2 = 0.1\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.1\), \(m = 10\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\). The fractional order \(\alpha\) was varied among the values \([0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 0.99]\). The corresponding basic reproduction numbers \(R_0\) for different \(\alpha\) values were calculated as \([0.3997, 0.4091, 0.4177, 0.4256, 0.4315]\). Figure 2 illustrates the results of the numerical simulations based on these parameter values.

In the condition \(R_0 < 1\) and \(\tau = 0\), Fig. 2 shows the dynamic behavior of the six compartments (Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Hospitalized, Recovered, Media), reflecting the propagation characteristics and final stability of the epidemic under different fractional orders \(\alpha = 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 0.99\). The susceptible, exposed, and infected compartments exhibit rapid changes in the early stages, with the peak values of exposed and infected populations decreasing as \(\alpha\) increases and the decline rates accelerating significantly, demonstrating that the propagation scale and dissipation speed of the epidemic are strongly influenced by the fractional order. The hospitalized population remains at a low level throughout the process and eventually approaches zero, while the recovered population gradually increases over time and stabilizes, reflecting the progressive control of the epidemic and the recovery of health. The media coverage compartment rises rapidly and reaches stability in a short time, indicating that media intervention effectively suppresses the scale of transmission and accelerates the recovery process in the early stages of the epidemic. As a result, the dynamic behavior of all compartments fully complies with Theorem 3.

Figure 3 shows the variation of the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) with respect to the fractional order \(\alpha\), based on the parameters provided in Condition 1. According to the expression for \(R_0\), its value is determined by the fractional powers of multiple parameters. As \(\alpha\) increases, the numerator terms \(\beta _1^\alpha \Lambda ^\alpha \varepsilon ^\alpha\) grow rapidly, while the denominator terms \((\varepsilon ^\alpha + d^\alpha )\) and \((d^\alpha + \delta _1^\alpha + \lambda ^\alpha + \mu _1^\alpha )\) increase at a slower rate, resulting in a monotonically increasing trend for \(R_0\). This phenomenon indicates that the fractional order \(\alpha\) has a significant impact on \(R_0\), higher fractional orders correspond to stronger transmission dynamics, while lower fractional orders may substantially weaken the transmission behavior.

Condition 2. The initial parameter values were set as follows: \(\Lambda = 5\), \(\beta _1 = 0.02\), \(\beta _2 = 0.01\), \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.00002\), \(\xi _2 = 0.00001\), \(\delta _1 = 0.1\), \(\delta _2 = 0.1\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.1\), \(m = 10\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\). The fractional order \(\alpha\) was varied within the set \([0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 0.99]\), and the time delay was introduced with \(\tau = 1\). From Eq. (4), the basic reproduction numbers \(R_0\) for \(\alpha = 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 0.99\) were \([0.3997, 0.4091, 0.4177, 0.4256, 0.4315]\). The outcomes of the numerical simulations under these parameter values are shown in Fig. 4.

Under the condition \(R_0 < 1\) and \(\tau > 0\), the dynamic behavior of each compartment exhibits significant changes. The exposed and infected compartments reach their peaks almost simultaneously under different fractional orders (\(\alpha\)), which contrasts sharply with the case of \(\tau = 0\), where the peak times vary with different fractional orders. However, after the introduction of time delay, the peak values of each compartment show significant differences with respect to the fractional order. In particular, the peak values of the exposed and infected compartments are noticeably higher for lower fractional orders (\(\alpha = 0.80, 0.85\)), while they are significantly reduced for higher fractional orders (\(\alpha = 0.95, 0.99\)). This indicates that the introduction of the time delay not only alters the dynamic characteristics of the system but also amplifies the effect of fractional orders on the peak values, which differs significantly from the behavior observed when \(\tau = 0\). Thus, the dynamic behavior of all compartments fully complies with Theorem 3.

Figure 5, based on Condition 2 (\(R_0 < 1\) and \(\tau = 10\)), illustrates the system dynamics under a fixed fractional-order parameter \(\alpha = 0.99\) with varying initial values for the compartments. The diagram shows that regardless of the initial conditions, all trajectories spiral towards the disease-free equilibrium \(E_0\), confirming the asymptotic stability described in Theorem 1.

Condition 3. The following initial parameter values were used: \(\Lambda = 5\), \(\beta _1 = 0.02\), \(\beta _2 = 0.01\), \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.00002\), \(\xi _2 = 0.00001\), \(\delta _1 = 0.1\), \(\delta _2 = 0.1\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.1\), \(m = 10\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\), and the fractional order was fixed at \(\alpha = 0.95\). At this point, the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) was calculated to be 0.4256. The delay parameter \(\tau\) was varied among the values \([1, 5, 10, 25, 50]\). Figure 6 illustrates the results of the numerical simulations under these parameter settings.

Figure 6 shows the dynamic behavior of each compartment under the fixed fractional order \(\alpha = 0.95\) and varying delay parameters \(\tau = 1, 5, 10, 25, 50\). The peak values of the exposed and infected compartments show significant differences with increasing \(\tau\), while the peak times remain consistent, indicating that the delay primarily adjusts the intensity of the transmission because the media delay modifies the strength and effects of media on the epidemic transmission. The media compartment is notably affected by \(\tau\), with its peak intensity increasing and the peak time significantly delayed as \(\tau\) grows. These results highlight the critical role of the delay parameter \(\tau\) in regulating the dynamic behavior of the epidemic, particularly in influencing latent transmission and media-driven effects. Furthermore, it also demonstrates that under the condition \(R_0 < 1\), the stability of each compartment is not affected by the delay \(\tau\).

Condition 4. The following initial parameter values were considered: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002\), \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\). The fractional order \(\alpha\) was varied among the values \([0.95, 0.96, 0.97, 0.98, 0.99]\). The basic reproduction numbers \(R_0\) were obtained as \([1.8284, 1.8798, 1.9326, 1.9869, 2.0427]\). Figure 7 presents the numerical simulation results based on these parameter values.

Figure 7 illustrates the dynamic behavior of each compartment under Condition 4 (\(R_0 > 1, \tau = 0\)). The susceptible population decreases over time and stabilizes, while the exposed, infected, hospitalized, recovered, and media compartments increase and eventually reach stable states. The fractional order parameter \(\alpha\) significantly affects the dynamic response speed of the system: larger values of \(\alpha\) accelerate the growth of the exposed, infected, and recovered compartments, allowing them to reach their steady states faster. The numerical simulations verify Theorem 4.

Based on the parameters under Condition 4, Fig. 8 illustrates the relationship between the fractional order \(\alpha\) and the basic reproduction number \(R_0\). As \(\alpha\) increases, \(R_0\) grows monotonically. The red horizontal line at \(R_0 = 1\) represents a critical threshold distinguishing the epidemic dynamics. For smaller values of \(\alpha\), \(R_0 < 1,\) indicating the disease will gradually die out. However, when \(\alpha\) exceeds the threshold of \(R_0 = 1\), the model indicates that disease transmission may persist and transition into a state of long-term propagation.

Condition 5. The following initial parameter values were used: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002,\) \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\), and the fractional order \(\alpha\) was varied among the values \([0.95, 0.96, 0.97, 0.98, 0.99]\). The corresponding basic reproduction numbers \(R_0\) were calculated for each \(\alpha\) value as \([1.8284, 1.8798, 1.9326, 1.9869, 2.0427]\). Two time delay conditions were considered: \(\tau = 200\) and \(\tau = 500\). Under these conditions, Figs. 9 and 10 illustrate the numerical simulations, respectively, based on the stated parameter values.

Under Condition 5 (\(\tau = 200\) and \(\tau = 500\)), the numerical simulations clearly illustrate the combined effects of the time delay \(\tau\) and the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha\) on the dynamical behavior of the model. When \(\tau = 200\), as the time delay does not exceed the critical value \(\tau _0\) required to trigger Hopf bifurcation, the system stabilizes, with all compartments eventually converging to steady equilibrium points. However, the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha\) significantly influences the peak values across compartments during this process. For instance, larger fractional orders (e.g., \(\alpha = 0.99\)) result in substantially higher peak values for the Infected and Media compartments compared to smaller fractional orders (e.g., \(\alpha = 0.95\)). This indicates that fractional orders not only affect the rate of epidemic spread but also play a crucial role in determining the severity of the epidemic peaks.

When \(\tau = 500\), the time delay greatly exceeds the critical value \(\tau _0\), leading the system dynamics to transition from stability to periodic oscillations. All compartments exhibit pronounced periodic fluctuations, particularly in the Infected, Exposed, and Media compartments, with the amplitude of these oscillations varying significantly across fractional orders. Larger fractional orders (e.g., \(\alpha = 0.99\)) correspond to higher oscillation amplitudes compared to smaller fractional orders (e.g., \(\alpha = 0.95\)), further highlighting the importance of fractional orders in regulating the system’s periodic behavior. Additionally, the time delay \(\tau\) determines whether the system stabilizes or transitions into periodic oscillations, while the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha\) significantly modulates the severity of epidemic peaks and the amplitude of periodic oscillations. Through numerical simulations, Theorem 5 has been verified.

Figure 11, based on Condition 5 (\(R_0 > 1\) and \(\tau = 10\)), illustrates the system dynamics under a fixed fractional-order parameter \(\alpha = 0.99\), showing that all trajectories, regardless of initial conditions, converge to the endemic equilibrium \(E^*\). This demonstrates that when \(R_0 > 1\), the epidemic cannot be eradicated and stabilizes at a persistent endemic state. The smooth and consistent convergence of trajectories highlights the stability of \(E^*\), verifying the theoretical results in Theorem 1.

Condition 6. We considered the following initial parameter values: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002,\) \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\), and the fractional-order parameter was fixed at \(\alpha = 0.99\). Numerical simulations were conducted under different time delay parameters, specifically \(\tau = 1, 50, 100, 300, 500\). Figure 12 presents the results of the numerical simulations based on these parameter settings.

Under the fixed fractional-order parameter \(\alpha = 0.99\) and different delay parameters \(\tau = 1, 50, 100, 300, 500,\) Fig. 12 illustrates the dynamics of each compartment in the model. When the delay parameter is small (e.g., \(\tau = 1, 50, 100\)), all compartments eventually stabilize without exhibiting any oscillatory behavior. However, as the delay parameter increases to \(\tau = 300\) and \(\tau = 500\), the system transitions from a stable state to periodic oscillations, with all compartments showing significant periodic fluctuations. Moreover, the amplitude of these oscillations grows as the delay increases. This phenomenon demonstrates that delays exceeding the Hopf bifurcation threshold significantly affect the system’s dynamics, inducing complex oscillatory patterns and underscoring the critical regulatory role of delays in epidemic models.

Condition 7. We considered the following initial parameter values: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002,\) \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\), and the fractional-order parameter was fixed at \(\alpha = 0.99\). Figures 13, 14, 15, and 16 illustrate the numerical simulation results for different time delay values (\(\tau = 100, 200, 300, 500\)) based on these parameter settings.

Figures 13, 14, 15, and 16 illustrate the impact of different time delay values (\(\tau = 100, 200, 300, 500\)) on the epidemic dynamics under the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha = 0.99\). When \(\tau = 100\) and \(\tau = 200\), the system demonstrates a stable spiral convergence, indicating that the epidemic gradually stabilizes with diminishing oscillations. As the time delay increases to \(\tau = 300\), the system transitions to a periodic oscillatory state, characterized by closed-loop trajectories and persistent fluctuations in the infected and recovered populations. At \(\tau = 500\), the periodic oscillations become more pronounced, with increased amplitude and complexity, reflecting the profound influence of time delays on the system’s dynamics. Smaller time delays facilitate faster epidemic stabilization, while larger delays may drive the system into sustained oscillatory patterns, revealing potential characteristics of recurrent epidemic waves.

From a practical perspective, these limit cycles typically reflect recurrent outbreaks and declines of diseases within populations. Under small time delays, the system can rapidly respond to feedback, driving the epidemic toward stabilization or attenuation. However, when the time delay exceeds a critical threshold, information lag leads to recurrent epidemic peaks at different time points rather than a single decline. The periodic solutions corresponding to recurrent outbreaks often stem from delayed responses by public health authorities and the public, failing to promptly suppress ongoing infection waves and resulting in resurgent periodic or multi-wave epidemics. In this context, the timeliness of intervention measures plays a decisive role in suppressing periodic fluctuations-if effective control cannot be implemented within critical time windows, the system may enter a high-amplitude oscillation zone, trapping the epidemic in a persistent “peak-valley” cycle. Notably, when epidemics exhibit periodic outbreaks, healthcare systems and societal resources face intensified pressure from repeated waves of impact. Conversely, maintaining the system dynamics within low-amplitude oscillations or stable regimes facilitates sustainable allocation of public health resources.

Condition 8. We considered the following initial parameter values: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002,\) \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\), and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were set as \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\), and the fractional-order parameter was fixed at \(\alpha = 0.95\). The delay parameter \(\tau\) varied within the range \([0, 500]\). Figure 17 shows the result of our numerical simulations based on the baseline parameter values stated.

In the numerical simulation shown in Fig. 17, we fix the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha = 0.95\), and let the delay parameter \(\tau\) vary within the range \([0, 500]\). It can be observed that when \(\tau\) is less than a certain threshold (approximately \(\tau \approx 150\)), the population size in each compartment (Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Hospitalized, Recovered) as well as the media intensity (Media) tends to stabilize, and no obvious periodic oscillations appear. However, once this threshold is exceeded, the system undergoes a Hopf bifurcation, all compartments begin to exhibit periodic oscillations, and the amplitude of oscillation continues to increase with increasing \(\tau\). This clearly indicates that in this model, the value \(\tau \approx 150\) acts as a “critical delay” and plays a decisive role in determining whether the system enters into periodic oscillations.

From the perspective of real-world epidemic transmission, the concept of “critical delay” reveals the crucial role of timely response in epidemic control. In the model, this delay refers to the time lag between the release of media reports and the moment when the susceptible population actually adopts protective measures, serving as the dividing line between system stability and periodic oscillations-when media information is quickly disseminated and the public responds in a timely manner, the epidemic tends toward stabilization or decline; conversely, if media coverage or public response lags beyond this critical point, the system will undergo repeated cycles of outbreak and decline, resulting in periodic or multi-wave epidemic patterns. In essence, this critical delay also reflects the lower limit of the efficiency of public communication and behavioral change: if media transmission is slow or the public fails to promptly adopt effective protective measures, the epidemic will fall into recurrent fluctuations, placing sustained pressure on healthcare systems and the socio-economic structure. Therefore, by improving the timeliness of media reporting, expanding the coverage of awareness campaigns, and enhancing public acceptance of protective measures, the delay can be maintained below the critical threshold, significantly reducing the amplitude of epidemic fluctuations, alleviating resource pressures, and promoting more effective epidemic control.

Condition 9. We considered the following initial parameter values: \(\Lambda = 100\), \(\beta _1 = 0.000021\), \(\beta _2 = 0.00002,\) \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.02\), \(\xi _2 = 0.01\), \(\delta _1 = 0.01\), \(\delta _2 = 0.01\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.01\), \(m = 1000\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\) and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial values for each compartment were \(X_0 = [2000; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0]\).The delay parameter \(\tau\) varied within the range \([0, 500]\) and the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha\) varied within the range \([0.90, 0.99]\). Figure 18 shows the result of our numerical simulations based on the baseline parameter values stated.

Under the parameter conditions \(\alpha = 0.90 - 0.99\) and \(\tau = 0 - 500\), Fig. 18 illustrates the dynamic behavior of the six compartments as influenced by variations in the fractional-order parameter and the delay parameter. As \(\alpha\) and \(\tau\) increase, the system exhibits progressively complex dynamics. When \(\tau < \tau _0\), all compartments stabilize without significant oscillations. However, when \(\tau > \tau _0\), the system undergoes bifurcation, with all compartments displaying periodic oscillations, and the amplitude of these oscillations intensifies with larger \(\tau\). Moreover, an increase in the fractional-order parameter \(\alpha\) amplifies the effects of delay, leading to more pronounced oscillations in the infected, hospitalized, and media-related compartments.

Model fitting

This section examines the fitting of Malaysia’s active COVID-19 case data to validate the feasibility of the proposed model. The dataset, spanning from March 24, 2020, to May 22, 2020, was obtained from the Ministry of Health Malaysia’s public records58. The numerical solution utilizes an explicit rectangular Product-Integration scheme, adapted to solve fractional-order delay differential equations with a single constant delay. Parameter estimation is conducted using the least-squares curve fitting method. After completing the fitting process, we validated the model’s effectiveness by performing segmented and overall error analysis using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Subsequently, we conducted sensitivity analysis by adjusting the proportional magnitudes of the estimated parameters to further investigate the impact of media-related parameters and time delay on the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia.

For model fitting, we utilized the active case data from Malaysia spanning from March 24, 2020, to May 22, 2020. The initial parameter values were configured as follows: \(\alpha = 0.91\), \(\tau = 0.6\), \(\Lambda = 0.5,\) \(\beta _1 = 0.00000101\), \(\beta _2 = 0.0000009\), \(\varepsilon = 0.01\), \(\xi _1 = 0.00002\), \(\xi _2 = 0.00002\), \(\delta _1 = 0.001\), \(\delta _2 = 0.001\), \(\mu _1 = 0.01\), \(d = 0.001\), \(m = 10\), \(\sigma _1 = 0.7\) and \(\sigma _2 = 0.1\). The initial state for each compartment was defined as \(X_0 = [33570000; 1423; 1423; 0; 0; 0]\). The fitting results are presented in Fig. 19, while the estimated parameters are summarized in Table 3. Additionally, the error analysis results segmented by time periods are summarized in Table 4.

Based on our numerical fitting results, the fractional-order model proposed in this study more accurately captures the rapid rise, peak, and subsequent decline of COVID-19 cases than the integer-order model, and thus aligns more closely with the observed data. To illustrate this, we used Malaysia’s active COVID-19 case data from March 24, 2020, to May 22, 2020, fitting both a fractional-order and an integer-order model to these data (as shown in Fig. 19) and comparing their outputs with actual records. The fractional-order model predicted the epidemic peak on Day 14, while the integer-order model predicted it on Day 16. In reality, the observed peak occurred on Day 12, indicating that the fractional-order model provides a more accurate prediction of the peak.

Malaysia implemented a Movement Control Order on March 18, 2020, with the media playing a pivotal role in its execution. Through various channels-including television, radio, newspapers, and social media-the media promptly disseminated the latest prevention policies, epidemic prevention knowledge, and expert analyses to the public, effectively fulfilling its role in information dissemination and public education. At the same time, the media quickly refuted rumors and misinformation while guiding public opinion, thereby alleviating panic, enhancing understanding and trust in the policies, and prompting the public to adopt strict self-protection measures such as maintaining social distancing and wearing masks. This combined effect not only significantly reduced interpersonal contact rates but also resulted in the infection count \(I\) in Fig. 19 exhibiting a rapid rise, reaching a peak within a short period, and then declining swiftly.

As shown in Table 4, during the initial stage (Days 1–20), the performance of the fractional-order and integer-order models is quite similar. However, in the later stages (Days 21–40 and Days 41–60), the advantage of the fractional-order model becomes increasingly evident. For instance, during Days 21–40, the fractional-order model achieves a MAPE of 4.04%, compared to 10.16% for the integer-order model; during Days 41–60, it records a MAPE of 3.71%, significantly outperforming the integer-order model’s 14.56%. Moreover, its nonlocal property means that the derivative at any given time depends not only on the current state but also on the entire history of the process, allowing it to more realistically capture long-range temporal interactions. As the epidemic evolves and historical effects accumulate, the fractional-order model’s superior ability to reflect delayed impacts and long-range interactions leads to more accurate predictions of epidemic trends.

Through Fig. 20, a local sensitivity analysis was conducted on 13 parameters in the model to investigate their impacts on the temporal variation of active cases. Parameters \(\xi _2\) and \(\delta _2\) were excluded from the analysis due to their negligible influence on active cases, as revealed by prior computational results. For media-related parameters, a higher \(\sigma _1\) accelerates the dissemination of epidemic-related information, enabling the public to obtain accurate updates more rapidly and adopt preventive measures (e.g., social distancing or mask-wearing), thereby effectively reducing transmission rates. Meanwhile, \(\sigma _2\) determines the duration of media influence; a lower \(\sigma _2\) implies that media impact may persist longer, helping the public maintain vigilance. Additionally, \(\tau\) characterizes the time lag between information release and public response. Sensitivity analysis shows that a larger \(\tau\) leads to a more pronounced delay in active case reduction, as critical information fails to reach the public promptly, hindering early containment of viral spread and potentially triggering subsequent larger-scale or recurrent outbreaks. Furthermore, \(\beta _2\) reflects the mitigation effect of media reporting on effective exposure; more effective media interventions enhance the suppression effect of \(\beta _2\), further reducing actual transmission rates. Regarding other parameters, a higher recovery rate shortens the infection period, thereby decreasing active cases, while a lower recovery rate prolongs the infection period and promotes epidemic spread. Notably, a higher fatality rate can partially impede large-scale transmission. For instance, the Ebola virus failed to achieve global proliferation due to its high fatality rate, whereas COVID-19 spread rapidly worldwide owing to its relatively lower lethality.

Therefore, our sensitivity analysis indicates that media-related parameters (\(\sigma _1\), \(\sigma _2\), and \(\tau\)), which govern the speed and dynamics of information dissemination, directly determine the timing and magnitude of the epidemic peak. Rapid media interventions (i.e., high \(\sigma _1\) and low \(\tau\)) can lead to an earlier and lower epidemic peak, whereas response delays (high \(\tau\)) result in a later and higher peak, as the virus gains more opportunities to spread freely during the lag in information propagation. Concurrently, sensitivity analysis of transmission parameters (\(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _2\)) reveals that even a slight increase in the baseline contact rate may destabilize the system, sustaining higher active case numbers. Thus, optimizing \(\sigma _1\), \(\sigma _2\), and \(\tau\) to maintain effective media interventions not only reduces the peak magnitude but also shortens the overall duration of the epidemic.

From a policy perspective, it is essential to establish a balanced and flexible media strategy. Governments and public health organizations should prioritize the timely release of accurate information and allocate resources to sustain long-term public engagement. This involves leveraging social media platforms, traditional media, and community-based initiatives to effectively reach diverse audiences. Furthermore, real-time monitoring of media interventions and adjustments based on public feedback and epidemic trends are critical to enhancing the effectiveness of these measures.

Conclusion and discussion

This study developed a delayed fractional-order SEIHR-M model incorporating media influence to investigate the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Malaysia. By introducing the Caputo fractional derivative, the model effectively captures the memory and nonlocal characteristics inherent in epidemic spread. Additionally, the media module with a delay term simulates the lagged effects of media interventions on public behavior. Theoretical analysis demonstrated the existence, non-negativity, and boundedness of the solutions, ensuring the biological feasibility of the model.

The basic reproduction number \((R_0)\) was derived as a key metric for evaluating disease transmission, and the stability of the equilibrium points was comprehensively analyzed. When \(R_0 < 1\), the disease-free equilibrium remains locally asymptotically stable, irrespective of the delay parameter \(\tau\). In contrast, when \(R_0 > 1\), two stability scenarios arise for the endemic equilibrium: if \(\tau = 0\), sufficient conditions for local asymptotic stability are provided; if \(\tau > 0\), there exists a critical delay \(\tau _0\). Specifically, the endemic equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable for \(0< \tau < \tau _0\), becomes unstable for \(\tau > \tau _0\), and undergoes a Hopf bifurcation at \(\tau = \tau _0\), leading to periodic oscillations. Numerical simulations validated these theoretical results and underscored the pivotal influence of fractional-order parameters and time delays on epidemic dynamics. Model fitting based on early COVID-19 data from Malaysia confirmed the model’s predictive accuracy and highlighted the significant role of media interventions in reducing infection peaks and controlling the epidemic. Building on these findings, error analysis and local sensitivity analysis demonstrated not only the model’s reliability and applicability, but also the critical importance of timely and sustained media interventions in effectively curbing the spread of the epidemic.

This paper provides an in-depth exploration of the dynamics of epidemic spread in Malaysia, with a particular focus on the impact of media reporting on the course of the outbreak. The study demonstrates that media interventions can not only significantly reduce the infection peak but also effectively delay the spread of the epidemic, thereby offering strong theoretical support for the government to adopt proactive media promotion and risk communication strategies in the early stages of an outbreak. Meanwhile, by incorporating a time-delay term in the media module, the research accurately captures the lag effect in behavioral changes following the receipt of information, further highlighting the critical role of timely and accurate information dissemination in epidemic control. The study also points out that if there is a significant delay in information transmission, the infection peak may become even more severe and potentially trigger cyclical rebounds.

Based on these findings, policy formulation should prioritize timely and continuous media interventions. This can be achieved by strengthening cross-departmental collaboration and information sharing to build a dynamic monitoring system that enables real-time communication among public health authorities, media regulators, and community managers. At the same time, refining media strategies and integrating multiple channels will ensure that accurate information is rapidly disseminated. Moreover, given the model’s demonstration of time-delay effects, it is crucial to continuously update the public on preventive measures and adjust intervention strategies as needed. Enhanced training for media professionals and government personnel, along with targeted public health education, is essential for maintaining information credibility and improving public awareness.

Although this study provides an initial insight into how media coverage regulates epidemic transmission, there is a need to further expand the modeling framework in several directions to more accurately capture the complex interactions between public opinion dynamics and disease spread. By incorporating time-varying parameters related to media influence-reflecting changes in media coverage and its effect on public behavior-the model can be enhanced to more accurately track real-world dynamics. Given that epidemics may manifest in multiple waves, with varying levels of public attention and government interventions in each wave, future work should adopt a “multi-wave epidemic” assumption. This would allow for a comparative analysis of potential media strategies across different waves and enable a dynamic adjustment of media interventions to achieve optimal or near-optimal overall control efficiency. Additionally, the early-warning function of media during multi-wave epidemics should be considered, providing more timely and effective information for governmental decision-making.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available and can be obtained from the Ministry of Health Malaysia’s public records58.

References

World Health Organization. COVID-19 dashboard. https://covid19.who.int (2020).

Our World in Data. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) statistics and research. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (2020).

The Straits Times. Malaysia declares nationwide lockdown from Wednesday as COVID-19 cases spike. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysia-declares-nationwide-lockdown-as-covid-19-cases-spike (2021).

Chang, D. S. & Wu, W. D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to construct a decision-making model. Sustainability 13, 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147610 (2021).

The Edge Malaysia. Surviving the impact of COVID-19: The tourism industry waits to cruise out of the doldrums. https://theedgemalaysia.com/article/surviving-impact-covid19-tourism-industry-waits-cruise-out-doldrums (2020).

Kermack, W. O. & McKendrick, A. G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 115, 700–721. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1927.0118 (1927).

Kermack, W. O. & McKendrick, A. G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. II. The problem of endemicity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 138, 55–83. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1932.0171 (1932).

He, S., Peng, Y. & Sun, K. SEIR modeling of the COVID-19 and its dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 101, 1667–1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-020-05743-y (2020).

Niu, R., Wong, E. W., Chan, Y. C., Van Wyk, M. A. & Chen, G. Modeling the COVID-19 pandemic using an SEIHR model with human migration. IEEE Access 8, 195503–195514. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3032584 (2020).

Youssef, H. M., Alghamdi, N., Ezzat, M. A., El-Bary, A. A. & Shawky, A. M. A proposed modified SEIQR epidemic model to analyze the COVID-19 spreading in Saudi Arabia. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 2456–2470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2021.06.095 (2022).

Wyss, A. & Hidalgo, A. Modeling COVID-19 using a modified SVIR compartmental model and LSTM-estimated parameters. Mathematics 11, 1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11061436 (2023).

Aziz, M. H. N. et al. Modelling the effect of vaccination program and inter-state travel in the spread of COVID-19 in Malaysia. Acta Biotheor. 71, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10441-022-09453-3 (2023).

Cheng, C., Aruchunan, E. & Aziz, M. H. N. Leveraging dynamics informed neural networks for predictive modeling of COVID-19 spread: A hybrid SEIRV-DNNS approach. Sci. Rep. 15, 2043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85440-1 (2025).

Bentout, S., Chekroun, A. & Kuniya, T. Parameter estimation and prediction for coronavirus disease outbreak 2019 (COVID-19) in Algeria. AIMS Public Health 7, 306. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2020026 (2020).

Soufiane, B. & Touaoula, T. M. Global analysis of an infection age model with a class of nonlinear incidence rates. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 434, 1211–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmaa.2015.09.066 (2016).

Djilali, S., Bentout, S., Kumar, S. & Touaoula, T. M. Approximating the asymptomatic infectious cases of the COVID-19 disease in Algeria and India using a mathematical model. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 13, 2250028. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793962322500283 (2022).

Omame, A. et al. Dynamics of Mpox in an HIV endemic community: A mathematical modelling approach. Math. Biosci. Eng. 22, 225–259. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2025010 (2025).

Ullah, M. A., Raza, N., Alshahrani, M. Y. & Omame, A. Analysis and interpretation of a novel malaria transmission mathematical model with socioeconomic structure. Nonlinear Dyn. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-10807-4 (2024).

Omame, A., Raezah, A. A., Okeke, G. A., Akram, T. & Iqbal, A. Assessing the impact of intervention measures in a mathematical model for monkeypox and COVID-19 co-dynamics in a high-risk population. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 10, 6341–6355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-024-02132-x (2024).

Bentout, S. & Djilali, S. Asymptotic profiles of a nonlocal dispersal sir epidemic model with treat-age in a heterogeneous environment. Math. Comput. Simul. 203, 926–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2022.07.020 (2023).

Bentout, S. Analysis of global behavior in an age?structured epidemic model with nonlocal dispersal and distributed delay. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 47, 7219–7242. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.9969 (2024).

Ibrahim, R. W. & Momani, S. On the existence and uniqueness of solutions of a class of fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 334, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmaa.2006.12.036 (2007).

Li, Y., Chen, Y. & Podlubny, I. Stability of fractional-order nonlinear dynamic systems: Lyapunov direct method and generalized Mittag–Leffler stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 1810–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2009.08.019 (2010).

Rezapour, S., Mohammadi, H. & Samei, M. E. SEIR epidemic model for COVID-19 transmission by caputo derivative of fractional order. Adv. Differ. Equ. 1–19, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02952-y (2020).

Aba Oud, M. A. et al. A fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 dynamics with quarantine, isolation, and environmental viral load. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03265-4 (2021).

Batiha, I. M., Momani, S., Ouannas, A., Momani, Z. & Hadid, S. B. Fractional-order COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: Modeling and stability analysis. Int. J. Biomath. 15, 2150090. https://doi.org/10.1142/S179352452150090X (2022).

Paul, S., Mahata, A., Mukherjee, S., Mali, P. C. & Roy, B. Fractional order SEIQRD epidemic model of COVID-19: A case study of Italy. PLoS One 18, e0278880. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278880 (2023).

Alalyani, A. & Saber, S. Stability analysis and numerical simulations of the fractional COVID-19 pandemic model. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 24, 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnsns-2021-0042 (2023).

Zarin, R., Khan, A., Yusuf, A., Abdel-Khalek, S. & Inc, M. Analysis of fractional COVID-19 epidemic model under caputo operator. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46, 7944–7964. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.7294 (2023).

Arshad, S., Siddique, I., Nawaz, F., Shaheen, A. & Khurshid, H. Dynamics of a fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 epidemic transmission. Phys. A 609, 128383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2022.128383 (2023).

Naik, P. A., Farman, M., Zehra, A., Nisar, K. S. & Hincal, E. Analysis and modeling with fractal-fractional operator for an epidemic model with reference to COVID-19 modeling. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 10, 100663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.padiff.2024.100663 (2024).

Caetano, C., Morgado, L., Lima, P., Hens, N. & Nunes, B. A fractional order sir model describing hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccination. Appl. Numer. Math. 207, 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnum.2024.10.001 (2025).

Carter, M. How twitter may have helped Nigeria contain Ebola. BMJ 349, g6946. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6946 (2014).

Sooknanan, J. & Comissiong, D. Trending on social media: Integrating social media into infectious disease dynamics. Bull. Math. Biol. 82, 86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-020-00757-4 (2020).

Mohsen, A. A., Al-Husseiny, H. F., Zhou, X. & Hattaf, K. Global stability of COVID-19 model involving the quarantine strategy and media coverage effects. AIMS Public Health 7, 587. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2020047 (2020).

Akdim, K., Ez-Zetouni, A. & Zahid, M. The influence of awareness campaigns on the spread of an infectious disease: A qualitative analysis of a fractional epidemic model. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 1311–1319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-021-01158-9 (2022).

Mao, Z. S. Dynamical Analysis of Time-Delay Neural Networks. Master’s thesis (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2008).

Liao, X. F., Li, X. M. & Wu, K. G. Stability, bifurcation, and chaos in time-delay neural networks: Progress in research. J. Chongqing Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 26, 32–36 (2003).

Agaba, G. O. & Soomiyol, M. C. Analysing the spread of COVID-19 using delay epidemic model with awareness. IOSR J. Math. 16, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.9790/5728-1603045259 (2020).

Liu, X., Lv, Z. & Ding, Y. Mathematical modeling and stability analysis of the time-delayed SAIM model for COVID-19 vaccination and media coverage. Math. Biosci. Eng. 19, 6296–6316. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2022294 (2022).

Jin, B. Fractional Differential Equations (Springer, 2021).

Huo, R., Wang, X. L. & Wu, G. R. Large existence and uniqueness of solutions for a class of fractional integral-differential equations with time-delay. J. Inner Mongolia Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 35, 169 (2014).

Zhang, Q. C. Bifurcation and Chaos Theory and Its Application (Tianjin University Press, 2005).

Wang, Z., Du, M. & Shi, M. Stability test of fractional-delay systems via integration. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 54, 1839–1846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4447-1 (2011).

Xiao, M., Jiang, G. P., Cao, J. D. & Zheng, W. X. Local bifurcation analysis of a delayed fractional-order dynamic model of dual congestion control algorithms. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 4, 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2016.7510151 (2017).

Li, T. & Xiao, Y. Complex dynamics of an epidemic model with saturated media coverage and recovery. Nonlinear Dyn., 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-021-07096-6 (2022).

Rai, R. K., Misra, A. K. & Takeuchi, Y. Modeling the impact of sanitation and awareness on the spread of infectious diseases. Math. Biosci. Eng. 16, 667–700. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2019032 (2019).

Misra, A. K., Sharma, A. & Singh, V. Effect of awareness programs in controlling the prevalence of an epidemic with time delay. J. Biol. Syst. 19, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218339011004020 (2011).

Diethelm, K. Monotonicity of functions and sign changes of their caputo derivatives. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 19, 561–566. https://doi.org/10.1515/fca-2016-0029 (2016).