Abstract

Cell adhesion and proliferation of zein-based scaffolds in tissue engineering are restricted due to hydrophobicity and low surface energy, and they are not appropriate for cell culture. Polycaprolactone (PCL) and zein are two distinct polymers in terms of origin and function; they are synthetic and natural polymers, respectively. In addition, PCL and zein have hydrophobic and amphiphilic structures. In this study we applied cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) for 4 min and 8 min to compare the effect of CAP on morphology, biodegradation, wettability, and chemical and biological features of zein and PCL-based nanofibrous structures. Our results presented that the water contact angle (WCA) of both types of nanofibers decreased after 4 and 8 min of treatment; PCL and zein contact angles after 8 min of treatment were 31.9 ± 7° and 30.3 ± 5° respectively. Chemical characterization confirmed that nanofibrous scaffolds were changed while functional groups were formed on scaffolds. Although biodegradation and cell attachment of scaffolds improved after treatment, most biodegradation rates belong to zein-P 8m; meanwhile, different CAP treatments have no negative effect on cell viability. With suitable cell viability, the potentials of zein and PCL in tissue engineering scaffolds could be improved. Based on SEM images, unlike zein, the synthetic PCL nanofibers aggregated and melted after CAP treatment, and PCL nanofiber morphology altered after 8 min treatment. At the same time, the results of other characterizations for zein and PCL fibers were approximately similar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Creating suitable biodegradable scaffolds that support cell adhesion, growth, proliferation, and differentiation, and that can guide the formation of new tissue, is one of the primary challenges addressed in tissue engineering1, Therefore, the attachment of cells to scaffolds is a critical factor that influences cell proliferation and differentiation2. Hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, surface roughness, surface charge, and surface properties are among the factors that affect cell adhesion3. Research indicates that a balanced level of hydrophilicity, a positive surface charge, textured surfaces, and high surface energy all contribute favorably to the attachment of cells4,5,6.

Over recent decades, electrospinning has been proven as an attractive technique for scaffold synthesis and biomedical engineering, due to its creation of scaffolds with a high surface area to volume ratio, porosity, similarity to extracellular matrix (ECM), good absorption, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and appropriate drug- encapsulated capacity7,8,9.

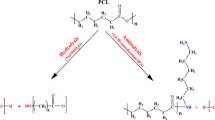

Polycaprolactone (PCL) and zein have been brought up as applicable polymer, among synthetic polymers, PCL has been approved as a biocompatible, biodegradable polymer. In spite of the mentioned advantages of PCL, it is a hydrophobic polymer and its wettability is low, so it cannot provide an appropriate field for cells adhering and proliferation10.

Natural polymers such as chitosan, starch, alginate, collagen, gelatin, and silk have attained attraction as promising materials for biomedical applications due to their biocompatibility and biodegradability11,12,13. Zein is a naturally occurring, bioactive, and antioxidant polymer derived from corn, it contains hydrophobic amino acid such as proline, leucine, and alanine and this causes to zein be amphipathic. Although zein is biocompatible, relatively affordable, safe, and able to be generated from renewable sources14, its amphiphilicity has negative effects on cell adhesiveness. Given this, zein administration as a scaffold has been restricted in labs and is not yet suitable for widespread commercialization15, To overcome this challenge, a range of surface treatments and modifications, including corona discharge, flame treatment, plasma exposure, electron beams, photon irradiation, ion beams, and X-ray application, have been employed to improve its surface characteristics16.

Plasma is categorized as thermal and non-thermal, sometimes known as cold atmospheric plasma, as a result of high-temperature electrons and heavy particles of thermal plasma, it cannot be used for temperature-sensitive polymer surface treatment, in comparison with thermal, non-thermal plasma is applicable in polymer surface modification. Since produced ions and naturals are cold, it is called cold atmospheric plasma (CAP)17,18. According to various studies, CAP is one of the most advanced techniques for modifying and enhancing the topographical and functional characteristics of surfaces. Its ability to produce highly reactive compounds without any associated toxicity makes it an excellent option for improving the biocompatibility of newly developed scaffolds. Additionally, CAP is used to produce biologically active compounds and supply ligands for cell integrins19,20,21.

Atyabi et al.18 made PCL nanofibrous scaffolds and functionalized them with cold plasma gas using a helium atmosphere (He 99.99 and 5% oxygen) for 30 s, which demonstrated that PCL nanofibers treated by helium cold plasma are porous, biocompatible and can provide a suitable platform for cell adhesion and growth.

Dong et al.22 performed research to develop nanofibrous scaffolds of zein modified with CAP, set at different time points including 5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 s at fixed voltage (65V). They indicated that CAP increases water vapor permeability, tortuosity, and it induces a transformation from β-turn and α-helix into β-sheet. They did not conduct any biological characterizations; it was anticipated that ACP modification could serve as a functional surface modification technique, which would improve zein film application in the packaging industry.

The purpose of this research is to evaluate the effect of CAP treatment on PCL and zein nanofibrous structures, to investigate whether the effect of CAP on hydrophobic (PCL) and amphiphilic (zein) polymers is different? Whether chemical, morphological, and biological characterization as well as biodegradability of nanofibrous scaffolds change after CAP treatment? Whether the effect of CAP modification on natural and synthetic polymers is different? Characterization techniques, including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), contact angle measurements, and in vitro biodegradation assessments, to analyze the chemical composition and morphology of the scaffolds were employed. After characterizing the scaffolds, our focus was shifted to evaluating their biological performance in vitro. It should be noted that although there are different studies which examine the effect of plasma treatment on PCL and zein separately, there is no study to assess CAP treatment on these polymers spontaneously.

Material and methods

Synthesis of zein and PCL scaffolds

Zein nanofibrous mats were manufactured by electrospinning (Electroris, FNM, Tehran, Iran), to summarize, zein was dissolved in glacial acetic acid 95% (v/v) at room temperature with the assistance of a magnetic stirrer overnight to form a polymer solution with a 30% w/v concentration, Then the polymer solution was transferred to a 5 ml syringe and needle connected to a high-voltage power supply; voltage and injection rate were about 20 kV and 0.5 ml/h23.

A 9.0% w/v polymer solution of PCL was made by dissolving it in a mixture of chloroform and methanol (7:3 v/v) under gentle stirring overnight at room temperature. The polymeric solution was pumped into a 5 mL syringe using an 18G stainless steel needle (with a blunt end), An applied voltage between the needle and the collector was 22 kV. The rotation speed was set at 300 rpm, and the injection rate was 1 ml/h23.

Plasma modification of zein and PCL nanofibrous scaffolds

Zein and PCL electrospun nanofibers were subjected to vacuum plasma treatment (Pardazesh, HP60 BF, Iran). The treatment was carried out under circumstances of 20% O2, 80% N2, and 100W for durations of 4 min and 8 min. It is worth mentioning that the applied radio frequency was around 13/56 MHz.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR)

To illustrate the distinctive chemical bonds, present in zein and PCL, and the newly formed chemical bonds on nanofibers after CAP surface modification for both 4-min and 8-min durations, FTIR spectroscopy (ABB Bomen, Canada) was conducted over a range of 500 to 4000 cm−1.

The scaffolds were chemically characterized using FTIR spectroscopy (ABB Bomen, Canada) within the range of 500–4000 cm−1.

Contact angle measurement

The surface hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the different groups were investigated using a water contact angle measurement system (KRUSS, Germany). The fibers (n = 3) were placed on a slide and 5 μl of DI water was applied to their surfaces. According to the literature, a hydrophilic surface has a contact angle of less than 90°, whereas a hydrophobic surface has a contact angle greater than 90°.

Structure and morphology of treated and untreated structures

The morphology, porosity, and diameter of nanofibers were typically examined using Scanning Field Emission Electron Microscopes (FE-SEM, TESCAN- Czech Republic), our treated and non-treated nanofibrous scaffolds were coated by Au, and imaging was done under an accelerating voltage of 25.0 kV. The acquired images were analyzed by Image J software (Java 1.8.0_172, NIH).

Assessment of porosity percentage

The Porosity percentage of nanofibrous mats was determined by the water replacement method (Archimedes Method) according to the following method (Eq. 1):

where V1, V2, and V3 are the primary volume of alcohol and the volume after submerging and removing the nanofibrous mats from water, respectively.

Biodegradation evaluation

The degradation of scaffolds immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was assessed over a period of 21 days by measuring weight loss. To achieve this, samples from different groups (n = 3) were weighed and then submerged in PBS at a temperature of 37 °C. Weights were recorded at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days. At each of these time intervals, the scaffolds were removed from the PBS, rinsed with deionized water, and then placed in a freeze dryer for 5 h to eliminate any residual moisture before weighing. The percentage of weight loss for the scaffolds was subsequently calculated using the following formula (Eq. 2):

W0: Weight before degradation, W1: Weight after degradation.

Cell adhering potential on nanofibrous structures

Nanofibrous scaffolds were disinfected with UV light and culture medium containing 2% Amphotericin B and Gentamicin. 4 × 104 NIH3T3 (Iranian Biological Resources Center, Iran) were seeded on prepared scaffolds and incubated in 37 °C and 5%CO2 for 5 days; after that, culture medium was removed, washed with PBS, and fixed with paraformaldehyde 4% for 30 min, and dehydrated in the freeze dryer for 48 h. To observe cell adhering on scaffolds, they were coated with gold and visualized by SEM.

For 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, a total of 4 × 104 NIH3T3 cells were seeded onto different scaffolds and cultured at 37 °C for 5 days. Following the incubation, the culture medium was withdrawn, and the seeded nanofibrous scaffolds were mounted with 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min. The samples were then washed with PBS and stained with DAPI (10 μg/ml). After the staining, the DAPI solution was removed, and the scaffolds were examined under a fluorescent microscope (NIB-100 F, Novel-China). Following that, DAPI staining images were quantified by Image J software (Java 1.8.0_172, NIH).

Cell viability assessment

Following the sterilizing process described earlier, the scaffolds were put on a 48-well plate. Then, 2.5 × 104 NIH3T3 cells were added to the scaffolds, and culture medium DMEM- high glucose (Gibco- USA) containing 10% FBS was poured on scaffolds and incubated at 37 °C and 5%CO2. For cell viability evaluation, the culture medium was removed and replaced with 300µl MTT (0.5 mg/ml), after 3 h incubation, MTT was removed, and 300 µl DMSO was added and gently shaken at room temperature. Consequently, the absorbance of samples was quantified with an ELISA reader (Biotech-USA) at the absorbance of 570 nm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) method, utilizing GraphPad Prism software, Version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Prism, Inc., San Diego, CA). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), with a p value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Surface characterizations

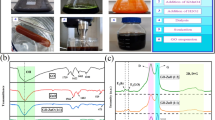

FTIR-ATR curves provide information on changes in functional groups of different nanofibrous scaffolds as depicted in Fig. 1. Based on ATR spectra of zein a peak about 3300 cm−1 in Amide A, which belongs to OH functional group and confirms zein presence15.

A more specific absorption band at 1720 cm−1 was observed in the Zein-P 4-min and Zein-P 8-min treated experimental groups, which correlates with the carbonyl group. The production of this new carbonyl group is attributed to the cleavage of peptide bonds24. In addition, small changes in movement and intensity of peaks in 750–1300 cm−1 region presented that plasma can improve C–O active group24. There is a peak at 3270 cm−1 region which is associated to O–H group and it is shifted to 3432 cm−1 after 4 min of plasma treatment24.

In non-treated PCL, A carbonyl sharp peak identified around 1720 cm−1, and CH2 vibration was located at 2942 and 2861 cm−1, wide absorption observed at 3300 and 3700 due to the O–H functional group in treated PCL17.

Contact angle measurement

The hydrophobic and amphiphilic nature of PCL and zein play a significant role in their surface properties and cellular behavior25,26,27, As a result, the contact angles of untreated PCL and zein were found to be greater than those of the surface-modified variants. Specifically, untreated PCL and zein nanofibers exhibited contact angles of 104.2 ± 6° and 96.3 ± 9°, respectively, while the treated samples showed reduced contact angles. Following 4 min of CAP treatment, the contact angles for PCL and zein samples were measured at 31.9 ± 7° and 30.3 ± 5°, respectively. After 8 min of treatment, the contact angles could not be assessed due to the substantial increase in wettability (Fig. 2).

Meghdadi et al.17 confirmed that contact angles of treated PCL nanofiber structures reduced from 118 ± 4° to 13.7 ± 1.4°.

Parallel with our results, Yildirim et al.28 reported a decrease in surface contact angles from 79.66° (non-treated) to 34.98° (treated) after a 5 min treatment. Dong et al.15 showed that the water contact angle of zein film treated with CAP-100V decreased from 72.85° to 47.43°.

As shown above, the primary contact angles of different polymers are different in various studies; they could be correlated to type of solution of different polymers29 and polymer solution pH30, it has been confirmed increasing pH decreased contact angles.

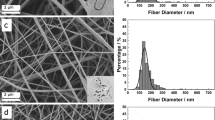

Microscopic analysis of treated and untreated zein and PCL nanofibers

To investigate the surface morphology and structure of PCL and zein nanofibers treated with CAP, all samples were observed by FE-SEM, the results indicated that non-treated PCL and zein exhibited uniform, smooth, randomly oriented, and bead-free structures. Moreover, matrices formed with zein and PCL were highly porous with interconnected structures, and the average diameters of zein and PCL nanofibers were about 246.5 ± 2 nm and 358.86 ± 10 nm, respectively. The SEM results showed that, although PCL scaffolds preserved their structure after 4 min’ treatment, but in PCL samples which treated 8 min by CAP, nanofibers were melted and aggregated (Fig. 3). Our results are aligned with another study, in which CAP-modified leads to PCL nanofiber aggregation after 5 and 8 min’ treatment17, Based on our observed results treated and non-treated zein scaffolds maintained their structure, and were not aggregated. In other studies, Wan et al. confirmed that plasma treatment less than 30 s not only has a negative effect on PLA nanofibrous morphology but also has a positive effect on it31. In contrast with our results, following the plasma treatment of PLGA and PLCL with NH3/Ar after 15 min, no morphological changes were observed in treated scaffolds32, It appears that morphological changes in nanofibers are influenced by the type of plasma treatment, treatment duration, and the material composition of the nanofibers.

As shown in Fig. 3, average diameter of PCL and zein nanofibers was increased after CAP treatment, and this result is coincident with pore diameter decreasing after treatment (Table1), studies presented that pore size, nanofiber diameter and nanofiber alignment can effect on cell behavior including activation, orientation, and infiltration33. Given that increasing nanofiber diameter has a negative affect pore diameter of nanofibers, it can prevent cell infiltration33, whereas cell attachment and MTT results presented that cell adherence and proliferation on CAP-treated surface have improved. It seems the functional group produced after CAP treatment developed cell adherence on nanofibers surfaces.

Biodegradation rate of manufactured nanofibrous scaffolds and porosity percentage

Since bio-implants should be degraded during implantation and replaced with new tissue, it is important to evaluate scaffold degradation in vitro. We quantified various nanofibrous degradation during a 21-day period; long-lasting scaffold degradation has happened in all experimental groups, the faster degradation rate belonged to Zein scaffolds, which were treated 8 min with CAP (38.3 ± 17%) on day 21, and based on our results, untreated zein and PCL scaffolds have minimum degradation (Fig. 4A). The enhancement of biodegradation rate of treated scaffold correlated with water contact angle decreasing, hydrophilicity improvement, and water absorption ability.

Based on the porosity percent measurement, obtained by Archimedes method, porosity percentage of nanofibrous scaffolds was in the range of 48.7–66.6%, and the effect of CAP on porosity % was not significance (Fig. 4B).

Cell adherence of NIH3T3 evaluation

Based on FE-SEM results, after 5 days cell viability was significantly supported in modified experimental groups. It means CAP treatment induce functional groups on nanofibers surface and this functional group play important role in cell attachment and proliferation (Fig. 5A). these results were confirmed with DAPI staining as shown in Fig. 5B and C.

(A) FE-SEM images of NIH3T3 Cell adherence on treated and non-treated nanofibrous scaffolds (B) DAPI staining of Zein, Zein-P 4 m, Zein-P 8 m, PCL, PCL-P 4 m, PCL-P 8 m scaffolds after 5 days’ cell culture (C) Quantification of DAPI staining of different scaffolds (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 5 presented that plasma treatment improves cell adherence and proliferation in treated scaffolds compared with non-treated scaffolds. This happens in both types of polymer nanofibers (PCL and zein). Zein fibers, which were treated by plasma for 8 min, were covered by NIH3T3 cells, and cells were completely speared on scaffolds. The results are coincident with the contact angle finding; no observable difference between cell shapes on different scaffolds was not distinguished. It is believed hydrophilic surfaces provide an appropriate field for extracellular matrix attachment and consequently improve cell adhesion34, since super hydrophilic surfaces absorb bacteria and other impurities, a suitable water contact angle for cell adhesion and proliferation is between 40 and 60°35. According to the results, CAP modification reduces the contact angle in Zein and PCL nanofibers, and after 4 and 8 min of modification, contact angle is lower than suitable range (40–60°), then again NIH3T3 attachment was improved. There is an indirect correlation between contact angle and cell attachment. It means by reducing contact angle, cell attachment increases, and cell growth id provided with an appropriate surface.

Cell viability

MTT results indicated that all experimental groups have no cytotoxic effects, and NIH3T3 cell viability was not decreased significantly in treated and non-treated samples compared with the control group after 1 and 2 days. It should be noted most groups show enhancement of cell viability, but this increase is not meaningful (Fig. 6).

Conclusion

This work assessed the morphology, chemical group, hydrophilicity, degradation, porosity, cell adherence, and proliferation after CAP treatment on Zein and PCL nanofibers. Zein is a natural and amphipathic polymer, and PCL is a synthetic and hydrophobic polymer. Our findings presented that CAP treatment induces functional groups on both zein and PCL nanofibrous scaffolds and decreases WCA and consequently promotes cell adhesion, proliferation, and viability. According to our results, although the effect of CAP treatment on zein, as a natural, and PCL, as a synthetic, nanofiber aggregation was different; cell attachment and cell viability of two kinds of polymers similarly changed after treatment. Specifically, the synthetic PCL nanofibers aggregated and melted after treatment, while zein did not show such changes. This finding indicates that the morphology of two polymers responded differently to the treatment, even though other characterization results were similar. In general, our results suggested that our treated scaffolds could be known as potential scaffolds for tissue engineering.

Data availability

Data available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Chapekar, M. S. Tissue engineering: Challenges and opportunities. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 53, 617–620 (2000).

Anselme, K. Osteoblast adhesion on biomaterials. Biomaterials 21, 667–681 (2000).

Shen, H., Hu, X., Yang, F., Bei, J. & Wang, S. Combining oxygen plasma treatment with anchorage of cationized gelatin for enhancing cell affinity of poly(lactide-co-glycolide). Biomaterials 29, 4219–4230 (2007).

Webb, K., Hlady, V. & Tresco, P. A. Relative importance of surface wettability and charged functional groups on NIH 3T3 fibroblast attachment, spreading, and cytoskeletal organization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 41, 422–430 (1998).

Hallab, N. J., Bundy, K. J., O’Connor, K., Moses, R. L. & Jacobs, J. J. Evaluation of metallic and polymeric biomaterial surface energy and surface roughness characteristics for directed cell adhesion. Tissue Eng. 7, 55–71 (2001).

Qiu, Q., Sayer, M., Kawaja, M., Shen, X. & Davies, J. E. Attachment, morphology, and protein expression of rat marrow stromal cells cultured on charged substrate surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 42, 117–127 (1998).

Bodillard, J., Pattappa, G., Pilet, P., Weiss, P. & Réthoré, G. Functionalisation of polysaccharides for the purposes of electrospinning: A case study using hpmc and si-hpmc. Gels 1, 44–57 (2015).

Szewczyk, P. K., Ura, D. P. & Stachewicz, U. Humidity controlled mechanical properties of electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (Pvdf) fibers. Fibers 8, 65 (2020).

Trabelsi, et al. Increased mechanical properties of carbon nanofiber mats for possible medical applications. Fibers https://doi.org/10.3390/fib7110098 (2019).

Desmet, T. et al. Nonthermal plasma technology as a versatile strategy for polymeric biomaterials surface modification: A review. Biomacromol 10, 2351–2378 (2009).

Zhang, K. & Van Le, Q. bioactive glass coated zirconia for dental implants: A review. J. Compos. Compd. 2 (2020).

Khan, A. U. R. et al. PLCL/Silk fibroin based antibacterial nano wound dressing encapsulating oregano essential oil: Fabrication, characterization and biological evaluation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 196, 111352 (2020).

Wöltje, M. et al. Functionalization of silk fibers by PDGF and bioceramics for bone tissue regeneration. Coatings 10 (2020).

Subuki, I., Nasir, K. N. A. & Ramlee, N. A. A review on the effect of zein in scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Pertan. J. Sci. Technol. 30, 2805–2829 (2022).

Dong, S., Guo, P., Chen, G., Jin, N. & Chen, Y. Study on the atmospheric cold plasma (ACP) treatment of zein film: Surface properties and cytocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 153, 1319–1327 (2020).

Martins, A. et al. Surface modification of electrospun polycaprolactone nanofiber meshes by plasma treatment to enhance biological performance. Small 5, 1195–1206 (2009).

Meghdadi, M. et al. Cold atmospheric plasma as a promising approach for gelatin immobilization on poly(ε-caprolactone) electrospun scaffolds. Prog. Biomater. 8, 65–75 (2019).

Atyabi, S. M. et al. Cell attachment and viability study of PCL nano-fiber modified by cold atmospheric plasma. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 74, 181–190 (2016).

Gümüşderelioǧlu, M. & Türkoǧlu, H. Biomodification of non-woven polyester fabrics by insulin and RGD for use in serum-free cultivation of tissue cells. Biomaterials 13, 3927–3935 (2002).

Şaşmazel, H. T., Manolache, S. & Gumusderelioglu, M. Water/O2-plasma-assisted treatment of PCL membranes for biosignal immobilization. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 20, 1137–1162 (2009).

Surucu, S., Masur, K., Turkoglu Sasmazel, H., Von Woedtke, T. & Weltmann, K. D. Atmospheric plasma surface modifications of electrospun PCL/chitosan/PCL hybrid scaffolds by nozzle type plasma jets for usage of cell cultivation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 385, 400–409 (2016).

Dong, S. et al. Surface modification via atmospheric cold plasma (ACP): Improved functional properties and characterization of zein film. Ind. Crops Prod. 115, 124–133 (2018).

Vogt, L., Liverani, L., Roether, J. A. & Boccaccini, A. R. Electrospun zein fibers incorporating poly(glycerol sebacate) for soft tissue engineering. Nanomaterials https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8030150 (2018).

Chen, G., Dong, S., Zhao, S., Li, S. & Chen, Y. Improving functional properties of zein film via compositing with chitosan and cold plasma treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 129, 318–326 (2019).

Dufay, M., Jimenez, M. & Degoutin, S. Effect of cold plasma treatment on electrospun nanofibers properties: A review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 4696–4716 (2020).

Narayanan, N., Kuang, L., Del Ponte, M., Chain, C. & Deng, M. Design and fabrication of nanocomposites for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration. Nanocompos. Musculoskelet. Tissue Regen. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-78242-452-9.00001-7 (2016).

Mahanty, A., Abbasi, Y. F., Bera, H., Chakraborty, M. & Al Maruf, M. A. Zein-based nanomaterials in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Biopolymer-Based Nanomaterials in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications 497–518 (Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820874-8.00006-3.

Yildirim, E. D. et al. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge plasma on the attachment and proliferation of osteoblasts cultured over poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffolds. Plasma Process. Polym. 5, 58–66 (2008).

Moshfeghian, M. et al. Effect of solution properties on electrospinning of polymer nanofibers: A study on fabrication of PVDF nanofibers by electrospinning in DMAC and (DMAC/Acetone) solvents. Adv. Appl. NanoBio-Technol. 2, 53–58 (2021).

Wu, Y., Du, J., Zhang, J., Li, Y. & Gao, Z. pH effect on the structure, rheology, and electrospinning of maize zein. Foods https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071395 (2023).

Wan, Y., Tu, C., Yang, J., Bei, J. & Wang, S. Influences of ammonia plasma treatment on modifying depth and degradation of poly(L-lactide) scaffolds. Biomaterials 27, 2699–2704 (2006).

Techaikool, P. et al. Effects of plasma treatment on biocompatibility of poly[(L-lactide)-co-(ϵ-caprolactone)] and poly[(L-lactide)-co-glycolide] electrospun nanofibrous membranes. Polym. Int. 66, 1640–1650 (2017).

Abbasi, N., Soudi, S., Hayati-Roodbari, N., Dodel, M. & Soleimani, M. The effects of plasma treated electrospun nanofibrous poly (ε-caprolactone) scaffolds with different orientations on mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation. Cell J. 16, 245–254 (2014).

Richards, R. G. The effect of surface roughness on fibroblast adhesion in vitro. Injury https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-1383(96)89031-0 (1996).

Wang, H. J., Fu, J. X. & Wang, J. Y. Effect of water vapor on the surface characteristics and cell compatibility of zein films. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 69, 109–115 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences grant number No. 400183 and with Ethical code: IR.RUMS.REC.1400.232.

Funding

This study was supported by Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences grant number No. 400183.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [Faezeh Esmaeili Ranjbar], Methodology: [Fatemeh Asadi, Mohammad reza Mirzaei], Formal analysis and investigation: [Sanam Mohandesnezhad, Mojgan Noroozi Karimabad], Writing—original draft preparation: [Faezeh Esmaeili Ranjbar]; Writing—review and editing: [Sadaf Mohandesnezhad], Funding acquisition: [Faezeh Esmaeili Ranjbar], Resources: [Ali Salehi Fathabadi and Mahboubeh Vatanparast], Supervision: [Afsaneh Esmaeili Ranjbar].

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.RUMS.REC.1400.232).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Esmaeili Ranjbar, A., Asadi, F., Mohandesnezhad, S. et al. Surface modification of electrospun polycaprolactone and zein using cold atmospheric plasma for tissue engineering applications. Sci Rep 15, 14567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99450-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99450-6