Abstract

In China, most colorectal cancer patients aged 65 years and above often suffer from poor psychological states, including high levels of anxiety and depression, as well as low resilience, due to the disease and its related symptoms. Analyzing the heterogeneity of anxiety, depression, and resilience in these patients can help intervene timely to improve their psychological well-being and prognosis. It was a cross-sectional study, and participants were recruited at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to determine the optimal latent profile model, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the differences across each latent profile, multinomial logistic regression was employed to analyze the influencing factors. 221 older colorectal cancer patients were identified and classified as low negative emotions and high resilience (49.8%), medium negative emotions, low and unstable resilience (30.8%) and high negative emotions and medium resilience (19.4%). There were significant differences in the scores of anxiety, depression, resilience and social support among these patients. Multinomial logistic regression showed that age, gender, marital status, employment, tumor size, positive lymph nodes, degree of differentiation, and social support were influential in these three profiles. Three heterogeneous subgroups of anxiety, depression, and resilience were identified among older patients with colorectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most widespread malignant tumors globally and the second leading cause of cancer mortality. More than half of colorectal cancer diagnoses and approximately three-fourths of colorectal cancer survivors are in individuals over the age of 651,2. Older patients are typically marked by comorbidities, a decline in organ performance, and an increased requirement for assistance with daily activities, all of which can exacerbate the health outcome of colorectal cancer3.

These older patients not only face adverse outcomes but also have to contend with fears about their own health, resulting in the onset of the two most prevalent negative emotions, namely anxiety and depression4. Nonetheless, healthcare providers in China tend to prioritize cancer treatment and overlook psychological comorbidities5. Both the family members of these patients and the patients themselves similarly always disregard mental health during the treatment process6. It has been reported that elevated levels of anxiety are connected to a higher risk of cancer recurrence and metastasis, as well as an increased rate of hospital readmission7,8. Depression is connected to reduced adherence to prescribed treatment and follow-up nursing care, immune deficiency, heightened inflammatory response, and lower survival outcomes in patients with common cancers9.

Resilience, a process of dynamic recalibration, is the capacity to adapt and modify one’s psychological distress and functioning performance when interacting with the environment10. Researchers have highlighted the value of resilience for colorectal cancer patients, as it can help to ease the stress caused by such a life-altering experience11,12. Previous studies revealed that colorectal cancer patients with high levels of resilience display decreased anxiety and depression13,14. Also, interventions to strengthen the resilience of colorectal cancer patients can help to lessen their anxiety and depression, and raise their quality of life12.

Based on the Stress Process Model15,16, we set out to explore the relationship among these three variables. The model points out that disease and its adverse outcomes can be considered as stressors, which, if perceived as a threat, may lead to psychological distress. In the treatment and recovery process of colorectal cancer, when confronted with unfavorable outcomes, older patients often turn to anxiety and depression as negative emotional coping mechanisms to defend against the stressors. Resilience, as a psychological trait, serves as a protective shield that assists older individuals in mitigating the detrimental effects of stress and negative emotions.

Social support is a system of family, friends, neighbors and community members who can supply psychological, physical, and financial aid to those with cancer during hard times17. Evidence suggests that resilience and social support can work together to help manage negative emotions, as the two are closely linked and social support can help to build resilience18. Social support is advantageous for individuals, both due to its direct influence and its ability to act as a buffer, protecting people from stressful life circumstances. So, social support for older colorectal cancer patients should be examined in order to better understand their relationships with depression, anxiety, and resilience.

Despite the numerous studies conducted on mental health among colorectal cancer patients4, the majority of previous research has focused on the variable or group level of mental health across all study participants. Examining the participants as an identical group, studies on mental health and its associated variables may be restricted in providing in-depth information. Therefore, the current state of anxiety, depression, and resilience in older patients with colorectal cancer is uncertain from an individual perspective.

Given this, latent profile analyses (LPA), a person-centered method, were employed to pinpoint distinct categories or subgroups in terms of depression, anxiety, and resilience based on individual responses to all measurements in this study. Most of the variables in the latent profile analysis were related to affective characteristics, thus social support was not included and was instead considered as an influencing factor. Therefore, this study aimed to (1) identify the different latent classes of depression, anxiety, resilience in older colorectal cancer patients by LPA, (2) investigate the factors that influence the latent classes of depression, anxiety, resilience in regard to demographic characteristics, clinical features, social support and provide targeted suggestions to enhance the psychological well-being of older patients with colorectal cancer.

Methods

Design and participants

It was a cross-sectional study, and participants were recruited at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. The recruitment took place 6 months after surgery between June and December 2021, using the convenience sampling method. colorectal cancer was diagnosed based on the criteria for stage I-III in the China Colorectal Cancer Diagnostic and Treatment Standard (2020 version)19. Participants were included if they were (1) aged 65 years or above; (2) with stable diseases 6 months after radical colorectal cancer surgery; and (3) with complete clinical information and regular in-hospital review. They were excluded if they (1) were diagnosed with other cancers or malignancies; and (2) had severe mental or psychological disorders. All participants signed a written informed consent form. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Department at Qingdao University (No. QDU-HEC-2021153) and was conducted in strict adherence to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Sample size

It is generally suggested that the sample size for multivariate statistics should be more than 10 events per variable20. In our study, the regression analysis included 17 observational variables, so the sample size should be a minimum of 170 people.

Measurements

A general information questionnaire was used to collect the sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics of the patients. Sociodemographic information included: age, sex, marital status, education, employment, medical insurance and family histories of cancer. Disease-related information included: tumor size, positive lymph nodes, TNM stage, degree of tumor differentiation, nerve injured, vascular cancer embolism, surgical procedure, chemotherapy times and radiotherapy.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

HADS consists of two subscales, Anxiety and Depression, with a total of 14 items, each with 7 items to assess levels of anxiety and depression respectively21. The total score for both subscales is 21, with scores of 0–7 indicating no symptoms, 8–10 indicating suspected anxiety or depression, and 11–21 indicating definite symptoms. The Cronbach’s α values for the anxiety and depression subscales in this study were 0.872 and 0.858 respectively, indicating good internal consistency of the scales.

Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

CD-RISC consists of three dimensions: tenacity (13 items), strength (8 items) and optimism (4 items), with a total of 25 items22. Each item is assessed using a five-level scoring system, ranging from “completely inconsistent” to “completely consistent,” with scores recorded as 0–4 points. The total score ranges from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores indicating greater resilience in the individual. The Cronbach’s α value of the scale in this study was 0.915.

Perceived social support scale (PSSS)

PSSS was used to measure the subjective perception of social support23. It consists of three dimensions: family support, friend support and significant other support, with a total of 12 items and a total score ranging from 12 to 84. Scores of 12–36 indicate a low level of perceived social support, scores of 37–60 indicate a medium level of perceived social support and scores of 61–84 indicate a high level of perceived social support. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale in this study was 0.870.

Data collection

Researchers received uniform training to ensure the consistency and standardization of the data collection process. All participants were informed of the study and any queries concerning the study or questionnaire were answered during data collection. We collected data through face-to-face interviews, as well as getting patient-related records from the electronic healthcare system.

Statistical analysis

Latent profile analysis on anxiety, depression and resilience were conducted using Mplus 8.3 software24. To enable comparison and explanation, all indicators (anxiety, depression, and resilience) were converted into Z-scores for Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) due to the different scoring methods used for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (four-point Scale) and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (five-point scale). We got the optimal model by gradually increasing the number of profiles from initial (one profile) to final (three profiles) and comparing the fit indices between them. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Sample Size-Adjusted BIC (aBIC) were used to assess the fitting level of models. Lower information criterion scores show better model fits. An entropy value was employed to indicate the accuracy of the latent profiles, with the value closer to 1 indicating a more accurate classification. If the value exceeds 0.8, the accuracy of the latent profiles is greater than 90%. The likelihood ratio test consists of the Vuong-Lo‐Mendell‐Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR) and the Bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). A pvalue below 0.05 indicates that the current model outperforms the previous one25.

After the optimal number of the latent profiles was determined, other statistical description and analysis were performed in SPSS 26.0 software. Count variables were reported as numbers and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). To examine the heterogeneity of social support, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In terms of anxiety, depression, and resilience, a one-way ANOVA and a post hoc test were used to compare the differences across each latent profile. We performed a multinomial logistic regression analysis to determine the factors influencing the latent profiles.

Results

Common method deviation test

Using Harman’s single factor test method, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA, unrotated) was conducted on all the measurement items. The results presented that the KMO was 0.852, the chi-square of the Bartlett spherical test was 6325.299 (p < 0.001), and 12 factors had characteristic roots larger than 1. The first common factor had a variance interpretation rate of 22.55%. The single-factor explanation variation in this study is not more than 40%, indicating that there is no considerable common methodology bias.

Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients

A total of 221 colorectal cancer patients were recruited for this study. The patients were mostly male (67.0%) and married (83.3%), with an age range of 65 to 81 (70.18 ± 4.06) years. Approximately two-thirds (67.4%) of the participants completed a junior school or higher education. For the majority of patients, the tumor is of high and moderate differentiation (81.9%), with a diameter of 5 cm or less (73.8%), and no nerve damage (61.5%) or vascular cancer embolism (62.0%). More than half of the patients had laparoscopic surgery (57.9%) and radiation therapy (66.1%). The mean scores of social support, anxiety, depression and resilience, and were 46.65 (SD = 10.42), 5.86 (SD = 4.10), 5.61 (SD = 3.95) and 54.03 (SD = 15.52), respectively. The characteristics of colorectal cancer patients are presented in Table 1.

Results of latent profile analysis (LPA)

Table 2 presented the fit indices for the one-to-four-profile model, and the optimal three-profile model was emphasized in bold. As the number of profiles increases from one to four, there is a consistent decrease in AIC, BIC, and aBIC. The entropy value of 0.972 is the highest of the 3-profile model. In all fitted models, the p-value of BLRT is consistently < 0.05, while the p-value of LMR is > 0.05 in the 4-profile model. After considering practical significance and interpretability, the three-profile model was determined to be the most fitting model. Table 3 showed that the average probability for profile 1 is 91.8%, for profile 2 is 91.0%, and for profile 3 is 92.2%. It indicated that the results of the three latent profile models were reasonable.

Naming of latent profile

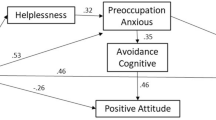

As presented in Fig. 1, of all the items, A1 ~ A7 belong to anxiety, A8 ~ A14 belong to depression, and B1 ~ B25 belong to resilience. There are three latent profiles on the anxiety, depression, and resilience.

Different latent profiles were classified and named based on the characteristics of the study variables. Profile 1 was categorized as “Low negative emotions and high resilience”. 110 patients (49.8%) had low anxiety, depression, and high resilience in the latent profile. Profile 2 was named “Medium negative emotions, low and unstable resilience”. It consisted of 68 patients (30.8%) who had moderate anxiety, depression, low and fluctuating resilience. Profile 3 was labeled “High negative emotions and medium resilience”. Those patients with high anxiety, depression, and moderate resilience were classified into the profile. The latent profile 3 included 43 patients (19.4%).

Comparison of anxiety, depression and resilience of colorectal cancer patients with different latent profiles

The comparison of anxiety, depression and resilience of patients with different latent profile between each latent profile is shown in Table 4. The analysis results showed that there were significant differences (p < 0.001) in the scores of anxiety, depression and resilience of patients between the three latent profiles. The post hoc test revealed that the scores for anxiety and depression in profile 1 were significantly lower than those of the patients in the other two profiles (p < 0.001). In addition, profile 1 scored significantly higher than the other profiles in terms of resilience (p < 0.001).

Comparison of social support of colorectal cancer patients with different latent profile

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the scores of the total and each dimension of the Perceived Social Support Scale among patients with three latent profiles. The results showed that the total scores and scores of the dimension of friend support were significantly different among patients with different latent profiles (p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the dimensions of family and significant other support (p > 0.05). The results and details were shown in Table 5.

Influences of factors on the latent profiles

A multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to discover the influence of patients’ sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics and social support on different latent profiles. High negative emotions and medium resilience (profile 3) served as the reference group. Compared to Profile 3, gender (OR = 22.239, p < 0.001), age (OR = 1.172, p = 0.028), tumor diameter (OR = 3.337, p = 0.025), positive lymph nodes (OR = 31.402, p = 0.026) and the scores for social support (OR = 1.106, p < 0.001) were seen to be significant in profile 1. Males (OR = 10.222, p < 0.001), married (OR = 0.064, p = 0.005) individuals, and those with a tumor diameter of 5 cm or less (OR = 3.426, p = 0.030) were found to have a higher likelihood of belonging to profile 2and the scores for social support were found to be significant (OR = 1.083, p = 0.009), when compared to profile 3. These results are shown in Table 6.

Discussion

To explore the heterogeneity of psychological symptoms experienced by older colorectal cancer patients, a latent model of anxiety, depression, and resilience was examined. Three profiles were finally identified: the low negative emotions and high resilience (Profile 1), the medium negative emotions with low and unstable resilience (Profile 2), and the high negative emotions and medium resilience (Profile 3).

The 49.8% of patients were classified as profile 1 (low negative emotions and high resilience), which had low levels of anxiety and depression and high levels of resilience. Regarding anxiety and depression, the scores for each item were the lowest among the three profiles. Concerning resilience, the scores for almost all items were the highest, except for items B9 (I feel that I can handle many things at a time) and B11 (I seldom wonder what the point of it all is), which showed lower scores. It is possible that the issue stems from older individuals experiencing adverse symptoms of diseases, leading to a decline in their functional independence26,27. As a result, they may develop a physical and psychological dependence and a lack of confidence in their abilities.

The 30.8% of patients were categorized as profile 2 (medium negative emotions with low and unstable resilience), which had medium levels of anxiety and depression, and low and unstable resilience. The scores for each item fell in the medium range for anxiety and depression across the three profiles. With regards to resilience, the scores for almost all items were the lowest, except for items B9 and B11, which showed the highest scores. It indicates that patients with colorectal cancer in this group have clear goals and a strong ability to self-regulate28.

The 19.4% of patients were sorted into profile 3 (high negative emotions and medium resilience), which had high levels of anxiety and depression and medium levels of resilience. In terms of anxiety and depression, the scores for each item were the highest among the three profiles. Resilience scores across all three profiles were in the medium range. Among these three groups, the patients in this group face the highest threat. Their levels of anxiety and depression were substantially higher than those of the other two groups. Given that these patients are confronted with such a dangerous situation, it is vital to conduct targeted psychological prevention and treatment in order to decrease the prevalence of anxiety and depression.

The results of a one-way ANOVA showed that the scores for anxiety, depression, and resilience were significantly different among the three latent profiles, suggesting a variation in psychological symptoms of older colorectal cancer patients. The patients belonging to profile 1 had a low level of anxiety and depression, whereas they had a high level of resilience. Those in this profile with minor emotional distress and a good psychological trait can preserve their mental health and quality of life, thus enabling them to face their disease and adverse outcomes with composure29. The patients belonging to profile 2 had a medium level of anxiety and depression, while they had a low and unstable level of resilience. It may be concluded that patients in this profile have maladaptive resilience, which results in their negative emotions rising rapidly. Previous studies have found that cancer survivors with weaker resilience usually experience stronger psychological distress, which is similar to the findings of this research30. The patients belonging to profile 3 had a high level of anxiety and depression, while they had a moderate level of resilience. Despite having medium resilience, the anxiety and depression levels of these patients were the highest. Numerous researchers believe that resilience is a protective factor for colorectal cancer patients in dealing with psychological stress13,31, yet this does not mean that these patients are not affected by negative emotions. A previous study has discovered that high levels of anxiety among female patients with breast cancer can diminish their resilience to moderate and alleviate pain related to the cancer in clinical settings32. This could be attributed to the fact that the nature of resilience is to improve the adaptation of those with sound mental health.

There were significant differences in the social support scores across the three profiles. The scores of the low negative emotions and high resilience profile were significantly higher than the other two profiles. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that social support can decrease negative emotions and improve resilience18,33,34. In terms of each dimension, friend support was the only dimension that showed a significant difference, while the others did not. Similarly, the scores for the dimension of friend support were the highest in the low negative emotions and high resilience profiles. Previous studies have given a satisfactory explanation. Colorectal cancer patients may have difficulty adapting to the postoperative conditions after surgery, such as wearing a stoma35. This situation may destabilize one’s self-awareness and physical image, potentially causing feelings of inferiority and disrupting close relationships with friends36. We can therefore conclude that it has caused a lack of support from friends of colorectal cancer patients.

In this study, age, gender, marital status, employment, tumor size, positive lymph nodes, degree of differentiation and social support were identified as influential factors in older adults with colorectal cancer.

Admittedly, social support is a major factor in influencing the mental health of colorectal cancer patients37. Studies have shown that social support can decrease psychological distress and promote resilience in patients with colorectal cancer18,38. Age is a significant protector for colorectal cancer patients from emotional distress. Patients with colorectal cancer in profile 1 (70.71 ± 4.36) were older than those in profile 3 (68.72 ± 3.20). This finding is consistent with existing research that has reported that the anxiety levels of older individuals can be lower when compared to those of younger individuals39. This is because cancer and its related issues have only a minor effect on their lives40. Unlike young people, they don’t have to stress over their job situation, financial situation, or family responsibilities41,42,43. Moreover, they have more effective emotional regulation strategies and a reduced desire to dictate the trajectory of their lives44. In addition, the multinomial regression analysis revealed that male gender could be a protective factor for colorectal cancer patients against poor psychological conditions. Evidence from prior research has shown the same perspective. Dr. Cohen and colleagues has reported that female colorectal cancer patients have a lower resilience score compared to males13. A study also discovered that females are more likely to experience anxiety and depression than males45. Being married can act as a shield against negative emotions for colorectal cancer patients. Reese et al. reported that the intimate relationship of partners could buffer emotional issues and depressive symptoms in colorectal cancer patients46. The results also showed that survivors of colorectal cancer who are employed generally have positive psychological condition. A study found that employment has been shown to promote social connections and enable individuals to engage more with their surroundings47. This friendly contact with the environment improves better mental health for this group of patients. With respect to disease-related characteristics, it has been reported that a tumor size of ≥ 5 cm is a risk factor for a poor prognosis in colorectal cancer48,49.Thus, we speculated that the unfavorable prognosis of colorectal cancer could cause negative emotions and weaken resilience. Positive lymph nodes may have an impact on the psychological condition of colorectal cancer patients. A study has reported that colorectal cancer with adverse histological features may lead to poorer clinical outcomes for patients50. At the same time, a systematic review has also confirmed that patients’ poor clinical features can influence their emotions4. The higher the degree of differentiation, the lower the likelihood of experiencing a poor psychological condition, which is similar to prior research48,51. Highly differentiated cancer is less malignant and has a more favorable prognosis. It indicates that these patients have a better chance of recovery, and as a result, their mental health is relatively good.

Therefore, we believe that managing psychological issues and strengthening resilience are equally important for those who are suffering from or have gone through serious diseases and adverse outcomes4. Based on the different profile characteristics of elderly colorectal cancer patients, we should implement targeted intervention strategies. For patients with the “low negative emotions and high resilience” profile, it is crucial to maintain their current psychological well-being. A randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of peer support on cancer survivors demonstrated that a peer support-exercise model has long-term potential to reduce comorbidities, improve physical and mental health, and significantly alleviate the disease burden of cancer survivors over 12 months52. For patients characterized by “medium negative emotions with low and unstable resilience,” enhancing resilience and further reducing negative emotions are crucial. A single-blind randomized controlled trial involving 120 cancer patients demonstrated that a mindfulness-based stress reduction program combined with music therapy led to decreased stress and depressive symptoms, as well as enhanced mental health53. Furthermore, findings from a quasi-experimental study investigating the impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions on resilience and life expectancy in patients with gastrointestinal cancer indicated that such interventions, particularly focusing on relaxation techniques like meditation, effectively boosted resilience and life expectancy in this patient population, thereby enhancing overall resilience levels54. Finally, for patients with the profile of “high negative emotions and medium resilience”, the focus is on reducing negative emotions while simultaneously enhancing resilience. A meta-analysis on cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors demonstrated significant improvements in depression and anxiety scores, with sustained benefits observed up to six months post-treatment55. A systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing interventions for enhancing resilience in cancer patients identified attention and interpretive therapy as the most effective among 12 interventions for bolstering mental resilience56. Cognitive intervention and positive psychological intervention were also found to be beneficial for enhancing mental resilience in cancer patients. Medical personnel should be attentive to the mental health of patients and offer psychological assistance so that they can make a good recovery and achieve an optimal quality of life57,58.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. Firstly, this study examined older colorectal cancer patients from one hospital through convenient sampling, which may have caused regional bias and limited sample representativeness; thus, it would be beneficial to sample from a broader range in future studies. Secondly, all measurements in this study are self-reported, which may introduce measurement bias. So, it is advisable for future research to include more objective measurement methods. Thirdly, due to study restrictions, some key influences such as self-efficacy, coping strategies, and collective resilience (community support or cultural resilience) and some moderators such as personality traits (neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness) were also not considered. These variables should be taken into account in upcoming research. Fourthly, this cross-sectional study demonstrated the correlation among depression, anxiety, mental resilience, and social support in elderly colorectal cancer patients. However, it did not establish causation between these variables. It remains uncertain whether higher social support leads to greater resilience or if stronger resilience results in increased social support. Subsequent longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the causal link between these factors.

Conclusion

There exists heterogeneity in depression, anxiety, and resilience among older colorectal cancer patients. We found three profiles, including “low negative emotions and high resilience”, “medium negative emotions, low and unstable resilience”, and “high negative emotions and medium resilience”. The social support in low negative emotions and high resilience group scored higher than that in “medium negative emotions, low and unstable resilience”, and “high negative emotions and medium resilience” groups. In order to reduce the level of negative emotion and elevate resilience in older colorectal cancer patients, medical staff should comprehend their individual characteristics and provide more targeted interventions aimed at maintaining their mental health.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license from the Qingdao University, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- CD-RISC:

-

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- PSSS:

-

Perceived Social Support Scale

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- LPA:

-

Latent profile analysis

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- aBIC:

-

Adjusted Bayesian information criterion

- LMRT:

-

Lo-Mendell-Rub test

- BLRT:

-

Bootstrap Likelihood ratio test

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

References

Siegel, R. L., Wagle, N. S., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A. & Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 233–254. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21772 (2023).

Miller, K. D. et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 363–385. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21565 (2019).

Sun, V., Reb, A., Debay, M., Fakih, M. & Ferrell, B. Rationale and design of a telehealth Self-Management, shared care intervention for Post-treatment survivors of lung and colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 36, 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-021-01958-8 (2021).

Cheng, V. et al. Colorectal Cancer and onset of anxiety and depression: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 29, 8751–8766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110689 (2022).

Hu, T., Xiao, J., Peng, J., Kuang, X. & He, B. Relationship between resilience, social support as well as anxiety/depression of lung cancer patients: A cross-sectional observation study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 14, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_849_17 (2018).

Zhu, H., Li, Z. & Lin, W. The heterogeneous impact of internet use on older People’s mental health: an instrumental variable quantile regression analysis. Int. J. Public. Health. 68, 1605664. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605664 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Mol. Psychiatry. 25, 3186–3197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00865-6 (2020).

Mausbach, B. T., Decastro, G., Schwab, R. B., Tiamson-Kassab, M. & Irwin, S. A. Healthcare use and costs in adult cancer patients with anxiety and depression. Depress. Anxiety. 37, 908–915. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23059 (2020).

Walker, J. et al. Major depression and survival in people with Cancer. Psychosom. Med. 83, 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000942 (2021).

Luo, D., Eicher, M. & White, K. Resilience in adults with colorectal cancer: refining a conceptual model using a descriptive qualitative approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 79, 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15464 (2023).

Sihvola, S., Kuosmanen, L. & Kvist, T. Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 56, 102079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102079 (2022).

Lin, C., Diao, Y., Dong, Z., Song, J. & Bao, C. The effect of attention and interpretation therapy on psychological resilience, cancer-related fatigue, and negative emotions of patients after colon cancer surgery. Ann. Palliat. Med. 9, 3261–3270. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1370 (2020).

Cohen, M., Baziliansky, S. & Beny, A. The association of resilience and age in individuals with colorectal cancer: an exploratory cross-sectional study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 5, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2013.07.009 (2014).

Tamura, S. Factors related to resilience, anxiety/depression, and quality of life in patients with colorectal Cancer undergoing chemotherapy in Japan. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 8, 393–402. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon-2099 (2021).

Pearlin, L. I. The sociological study of stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 30, 241–256 (1989).

Ii, D. G. B. & Kaplan, B. H. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. (Handbook of the sociology of mental health /).

Kyriazidou, E. et al. Health-Related quality of life and social support of elderly lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. SAGE Open. Nurs. 8, 23779608221106444. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608221106444 (2022).

Çakir, H., Küçükakça Çelik, G. & Çirpan, R. Correlation between social support and psychological resilience levels in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a descriptive study. Psychol. Health Med. 26, 899–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1859561 (2021).

[Chinese Protocol of Diagnosis and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 58, 561–585, (2020). edition)] https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112139-20200518-00390 (2020).

Hair, J. F. Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Edition). (2009).

Snaith, R. P. & Zigmond, A. S. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Bmj 292, 344–344 (1986).

Yu, X. et al. (CD-RISC) WITH CHINESE PEOPLE. Social Behav. Personality: Int. J. 35, 19–30 (2007).

Blumenthal, J. A. et al. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 49, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198707000-00002 (1987).

Muthén, L. et al. Mplus user’s guide. (1998).

Bouveyron, C., Celeux, G., Murphy, T. B. & Raftery, A. E. Model-Based Clustering and Classification for Data Science: with Applications in R (With Applications in R, 2019). Model-Based Clustering and Classification for Data Science.

Luciani, A. et al. Fatigue and functional dependence in older cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 424–430. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0b013e31816d915f (2008).

van Abbema, D. et al. Functional status decline in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer after cancer treatment: A prospective cohort study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 8, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.01.003 (2017).

Barlow, M. A., Wrosch, C. & McGrath, J. J. Goal adjustment capacities and quality of life: A meta-analytic review. J. Pers. 88, 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12492 (2020).

Ye, Z. J. et al. Predicting changes in quality of life and emotional distress in Chinese patients with lung, gastric, and colon-rectal cancer diagnoses: the role of psychological resilience. Psychooncology 26, 829–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4237 (2017).

Harms, C. A. et al. Quality of life and psychological distress in cancer survivors: the role of psycho-social resources for resilience. Psychooncology 28, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4934 (2019).

Lim, C. Y. S. et al. Fear of Cancer progression and death anxiety in survivors of advanced colorectal cancer: A qualitative study exploring coping strategies and quality of life. Omega (Westport). 90, 1325–1362. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221121493 (2025).

Liesto, S. et al. Psychological resilience associates with pain experience in women treated for breast cancer. Scand. J. Pain. 20, 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2019-0137 (2020).

Costa, A. L. S. et al. Social support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life and resilience in Brazilian patients with colorectal Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 40, 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000388 (2017).

de Andrade, T. B., de Andrade, B., Viana, M. C. & F. & Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its association with social support among older adults: the Brazilian National health survey. J. Affect. Disord. 333, 468–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.051 (2023).

Xian, H. et al. Cross-sectional study among Chinese patients to identify factors that affect psychosocial adjustment to an enterostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage. 64, 8–17 (2018).

Smith, J. A., Spiers, J., Simpson, P. & Nicholls, A. R. The psychological challenges of living with an ileostomy: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychol. 36, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000427 (2017).

Dunn, J. et al. Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology 22, 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3210 (2013).

Haviland, J. et al. Social support following diagnosis and treatment for colorectal cancer and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the UK colorectal wellbeing (CREW) cohort study. Psychooncology 26, 2276–2284. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4556 (2017).

Weiss Wiesel, T. R. et al. The relationship between age, anxiety, and depression in older adults with cancer. Psychooncology 24, 712–717. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3638 (2015).

Hossain, N., Prashad, M., Huszti, E., Li, M. & Alibhai, S. Age-related differences in symptom distress among patients with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 14, 101601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2023.101601 (2023).

Blank, T. O. & Bellizzi, K. M. A gerontologic perspective on cancer and aging. Cancer 112, 2569–2576. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23444 (2008).

Sammarco, A. Quality of life of breast cancer survivors: a comparative study of age cohorts. Cancer Nurs. 32, 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e23b7 (2009). quiz 357 – 348.

Nelson, C. J. et al. The chronology of distress, anxiety, and depression in older prostate cancer patients. Oncologist 14, 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0059 (2009).

Castrellon, J. J., Zald, D. H., Samanez-Larkin, G. R. & Seaman, K. L. Adult age-related differences in susceptibility to social conformity pressures in self-control over daily desires. Psychol. Aging. 39, 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000790 (2024).

Lloyd, S. et al. Mental health disorders are more common in colorectal Cancer survivors and associated with decreased overall survival. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1097/coc.0000000000000529 (2019).

Reese, J. B., Lepore, S. J., Handorf, E. A. & Haythornthwaite, J. A. Emotional approach coping and depressive symptoms in colorectal cancer patients: the role of the intimate relationship. J. Psychosoc Oncol. 35, 578–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2017.1331492 (2017).

Aminisani, N., Nikbakht, H. A., Shojaie, L., Jafari, E. & Shamshirgaran, M. Gender differences in psychological distress in patients with colorectal Cancer and its correlates in the Northeast of Iran. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 53, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-020-00558-x (2022).

Yan, Q. et al. Value of tumor size as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer patients after chemotherapy: a population-based study. Future Oncol. 15, 1745–1758. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2018-0785 (2019).

Yirgin, H. et al. Effect of tumor size on prognosis in colorectal cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 94, 63–72 (2023).

Lu, J. Y. et al. [Oncological outcomes analysis of colorectal cancer with unfavorable histological features]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 56, 843–848. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2018.11.010 (2018).

Hyngstrom, J. R. et al. Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the National Cancer data base. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19, 2814–2821. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2321-7 (2012).

Adlard, K. N. et al. Peer support for the maintenance of physical activity and health in cancer survivors: the PEER trial - a study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 19, 656. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5853-4 (2019).

Yildirim, D., Çiriş Yildiz, C., Ozdemir, F. A., Harman Özdoğan, M. & Can, G. Effects of a Mindfulness-Based stress reduction program on stress, depression, and psychological Well-being in patients with cancer: A Single-Blinded randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 47, E84–e92. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000001173 (2024).

Garagoun, S. N., Mousavi, S. M., Shabahang, R. & Bagheri, F. & Sheykhangafshe. The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention on Resilience and Life Expectancy of Gastrointestinal Cancers Patients. (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 12, 21466. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25068-7 (2022).

Ding, X. et al. Effects of interventions for enhancing resilience in cancer patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 108, 102381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2024.102381 (2024).

Lloyd-Williams, M., Cobb, M., O’Connor, C., Dunn, L. & Shiels, C. A pilot randomised controlled trial to reduce suffering and emotional distress in patients with advanced cancer. J. Affect. Disord. 148, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.013 (2013).

Wang, P., Pang, X., He, M. & Liu, J. Effect of Stepwise psychological intervention on improving adverse mood and quality of life after colon cancer surgery. Am. J. Transl Res. 15, 4055–4064 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for their involvement in the study.

Funding

This current work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (NO. ZR2020MG057).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QD: conceptualization, writing original draft and writing– review & editing; TW: writing– review & editing, data collection, data curation and software; XLB: data collection, data curation and software; LPC: data curation, software; FZ: supervision, writing– review & editing; CPL: funding acquisition, project administration and writing– review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics declarations

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao University (NO. QDU-HEC-2021153). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Q., Wang, T., Bu, X. et al. Latent profile analysis of anxiety, depression, and resilience among elderly colorectal cancer patients in China. Sci Rep 15, 14897 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99493-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99493-9