Abstract

The export coefficient model (ECM) remains widely applied in estimating agricultural Non-point Source Pollution (NPSP) due to its simplicity, minimal parameter requirements, and relatively high accuracy. However, its reliance on empirical export coefficient (EC) limits its ability to accurately quantify pollutant loads in large and complex watersheds. This necessitates the development of more advanced approaches for improved pollutant load estimation. To overcome these challenges, the EC-ICM integrates environmental factors with optimized EC values for various land use types, enhancing its adaptability for watershed management. Empirical EC values were derived using genetic algorithm (GA) and Latin hypercube sampling, then improved EC and corrected EC were employed to estimate pollutant discharge and water inflow across land uses. The model incorporates multiple factors—such as surface runoff, topographic influence, landscape interception, soil erosion, pollutant production, water leaching, and cost-distance—allowing for more accurate NPSP load assessments. Pollution factors were classified using the natural breaks method, with Entropy Weight method determining weights for a comprehensive multi-factor evaluation and risk-level assignment. Compared to ECM optimized solely with GA, the EC-ICM demonstrates improved accuracy, reducing the relative error of total nitrogen and total phosphorus by 9.66% and 6.68%, respectively. Land use contributes the highest share of TN loads, particularly from cropland and grassland, followed by livestock and population sources. TP loads are primarily attributed to livestock and poultry farming, followed by land use and population sources. The Longdong Loess Plateau, responsible for approximately 12% of total NPSP loss, is identified as a high-risk area. Targeted zoning management strategies based on risk analysis prioritize these high-risk regions, providing practical recommendations for pollution control and comprehensive watershed environmental management. Future research can further explore the impact of improving temporal resolution, future climate change and combining hydrodynamic models on the ability to simulate the amount of pollutants entering the river.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-point Source Pollution (NPSP) is characterized by its random occurrence, intermittent processes, complex mechanisms, uncertain emission pathways and quantities, as well as the spatiotemporal variability of its pollutant loads. These factors, coupled with challenges in simulation and control, make it difficult to accurately quantify these pollutants and assess their nationwide impact1,2.

Agricultural NPSP primarily consists of pollutants such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and pesticides, which are transported into water bodies via rainfall runoff resulting from agricultural activities. Furthermore, the formation of agricultural NPSP is influenced by multiple factors, including climate, terrain, and farming practices. The complexity of these emission pathways further complicates efforts to control pollution3. The NPSP load in the Yellow River Basin (YRB) has significant seasonal variation, which is mainly affected by precipitation patterns and agricultural activities. Precipitation in the basin is concentrated from June to September, accounting for more than 60% of the annual precipitation. Heavy rainfall is prone to surface runoff, resulting in a large input of pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus, making this period a high-risk period for NPSP4. In addition, spring and autumn are critical periods for crop fertilization, and the flushing effect of precipitation after fertilization may intensify the transport of pollutants into water bodies5. Therefore, accurately identifying pollution sources and loads, quantifying their characteristics, and developing precise assessment models have become central areas of current research6. These steps are essential for formulating effective pollution control strategies. The identification of pollution source areas typically employs methods such as the Pollution Index method7,8, Export Coefficient Model (ECM)9, Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)10, and the Universal Soil Loss Equation (ULSE)11. These approaches aid in pinpointing risk zones and primary pollution sources within a watershed, enabling targeted prevention, control, and management of agricultural NPSP risks at the county level. Such targeted interventions can substantially enhance the efficiency of pollution control and provide scientific support for the development of watershed pollution management strategies.

To quantify the load of agricultural NPSP, various models have been developed, including the Agricultural Management System Chemical Runoff and Erosion (CREAMS)12, the Non-Point Source Watershed Environmental Response Simulation (ANSWERS)13, and the Rural Watershed Water Resource Simulator (SWRRB)14,15. Among these, ECM aims to estimate pollutant loads under different land use types, with particular emphasis on dissolved pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Due to its low data requirements and ease of use16,17, ECM has become a widely utilized tool for pollutant load estimation18,19,20,21,22. Despite its broad application in agricultural NPSP research, ECM has certain limitations, particularly when addressing complex factors such as the spatiotemporal distribution of precipitation, soil conditions, and topographic variations. These limitations result in reduced accuracy when the ECM is applied to regions with uneven precipitation patterns or complex terrain23. For instance, ECM typically fixed ECs for specific land use types, neglecting the significant influences of factors such as land use, climate, topography, hydrological features, soil type, and vegetation cover on these coefficients24. Moreover, the model does not adequately account for variations in livestock farming practices, the effects of precipitation under different climatic conditions, or the impacts of topographic changes, all of which can lead to inaccurate model outcomes25,26,27. As a result, adjusting ECs based on land use types, regional climate, watershed characteristics, and human activities essential for enhancing the model’s applicability and accuracy in complex environments28.

Therefore, an increasing number of studies have sought to optimize ECM by incorporating various environmental driving factors. These factors include rainfall24,29, land use types30, retention coefficients31, sediment emission32, topographic factors33, and other key influencing factors31 to refine simulation results. The distance between pollutants and rivers affects the degree of nutrient attenuation during the runoff process, which has also been increasingly considered and quantified in recent studies34. However, the shortest weighted distance from each grid point to the nearest river source has not yet been included in the analysis. Previous studies have typically focused on pollutant loads generated by various sources, without considering the loss of pollutants during their migration to receiving water bodies35,36. Therefore, the introduction of river entry coefficients allows for a more accurate reflection of pollutant transport and transformation across spatial units, thus enhancing the precision of pollutant load estimates and providing a comprehensive evaluation of the actual impact of pollutant sources on water bodies37. Furthermore, most studies on improved ECM have focused on small watersheds, with limited verification of total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) loads from NPSP in large basins. Consequently, the study focuses on the YRB, integrating multiple driving factors to improve output coefficients, including the cost-distance factor, and enhancing river entry coefficients to construct the EC-ICM model. The improved EC-ICM model is used to estimate spatial NPSP loads. By comparing observed and simulated values, the model’s feasibility and accuracy in large basin estimations are validated, and a comprehensive assessment of NPSP is conducted. The main objectives are: (i) to use Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) and genetic algorithm (GA) to optimize the pollutant ECs for different land use types, incorporating the impact of multiple environmental driving factors, and to construct and validate the EC-ICM with enhanced spatial distribution capability for YRB; (ii)to estimate the pollution intensity from three non-point sources—agriculture, population, and livestock, and to calculate the pollutant discharge and river inflow of TN and TP across different sub-basins as well as their respective contribution rates; (iii) to develop a comprehensive risk assessment model for NPSP based on multiple environmental driving factors, such as vegetation cover, slope, and soil erosion, providing risk-based partitioned management strategies for watershed pollution and actionable suggestions for pollution control measures. Despite the absence of long-term real-time monitoring data and high-precision environmental data, the proposed model provides an effective, operational, and widely applicable solution. It successfully addresses the limitations of traditional models in handling the spatial heterogeneity of watersheds, making it particularly suitable for regions with limited data or monitoring capabilities.

Methods

Study area and data sources

Study area

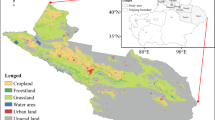

The Yellow River Basin (Fig. 1), situating in northern China (95°53′–119°15′ E, 32°10′–41°50′ N), originates from the Bayan Har Mountains on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. It flows through Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Henan, and Shandong province, and is geographically segmented into upper, middle, and lower reaches, with boundaries defined by Hekou Town in Inner Mongolia and Taohuayu in Henan. The basin is primarily situated within the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the monsoon climatic zone, with abundant sunlight and significant seasonal temperature variations. The average annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 1200 mm, decreasing progressively from south to north38. Precipitation in the Yellow River Basin has a significant seasonal distribution, which is mainly affected by the East Asian monsoon. The precipitation in the upper reaches is relatively low, while the middle reaches have frequent heavy rainfall in summer, which can easily cause soil erosion and pollutant migration. In this basin, spring and autumn are the main crop growth and fertilization periods. If there is precipitation after fertilization, nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus may enter the water body with runoff, increasing the pollutant load. In addition, although there is less precipitation in winter and surface runoff is not obvious, soil freezing may cause pollutants to accumulate and enter the river with surface runoff during the spring snowmelt period of the following year. While the annual average temperature varies between − 18.4 and 16.1 °C. The total basin area spans 795,000 km2, with grassland, cultivated land, and forest land constituting 48.47%, 24.68%, and 13.22% of the basin respectively. Among the 121 soil subtypes, the predominant types are turf soil, yellow cotton soil, wind-blown sand, and frigid calcareous soil. Feedback from central environmental protection inspectors across nine provinces revealed significant delays in the development of environmental infrastructure, including low inflow concentrations at sewage treatment plants, illegal sludge disposal, slow improvements in sewage treatment quality and efficiency, insufficient pollution interception and management efforts, and inadequate measures to prevent agricultural NPSP. Consequently, accurately estimating agricultural NPSP intensity and classifying pollution levels is crucial for effective protection and management, as well as for promoting ecological conservation and high-quality development.

Study area location (a: DEM; b: location; c: land use; d: precipitation distribution; e: NDVI) of the Yellow River Basin. (Fig. 1. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

Database source

432 counties within the nine sub-basins (TNH, XHY, BYGL, SHHK, WJZX, LM, TG, XY, and LK) of in the YRB was evaluated from 2021 to 2023 using TN and TP indicators. The data types and descriptions could be found in Table 1. NPSP majorly comprises contributions from urban and rural population, the livestock and poultry industries, and various land use types. Pollutants carried by urban rainwater runoff diffuse into rivers, while fertilization and pesticide activities in green spaces and horticultural areas complicate the widespread distribution and control of urban pollution sources, leading to urban pollution that exhibits typical NPSP characteristics. Therefore, urban and rural populations are classified as NPSP contributors. Meanwhile, point sources are considered pollution sources distinct from the non-point sources described above. The ECs for livestock and poultry are calculated based on the EC recommended by the National Environmental Protection Administration39, while the EC for the rural population is based on relevant research40, with further details provided in Table 2.

Research framework

The EC-ICM framework for NPSP modeling developed is illustrated in Fig. 2. Initially, LHS and GA optimization methods are employed to calculate the ECs for different land use types across nested sub-basins. LHS generates a reasonable sample space for input variables, while GA minimizes the model’s relative error by iteratively optimizing the ECs. Subsequently, based on the calculated initial ECs, the proportional measure of normalized values of surface runoff factor (RI) and either soil water leaching (LI) or the soil erosion factor (K) to the landscape interception factor (LII) is used as a weight factor to calibrate ECs of pollutants in different spatial units. Finally, the ratio of the product of rainfall erosivity factor (α) and topographic influence factor (β) to the product of cost-distance factor (δ) and vegetation coverage factor (f) is applied as the weight factor for TN and TP. This further calibrates ICs of pollutant sources and enables spatial representation. This model effectively simulates the spatial distribution of agricultural NPSP within a watershed, providing a scientific basis for developing watershed pollution control strategies and conducting pollution risk assessments.

Figure 2 delineates the innovative framework for estimating the discharge and inflow of NPSP by modified ECs and ICs of different land use types. \(L{T}_{N}\) represents improved EC of TN, \(L{T}_{P}\) denotes modified EC of TP, \({\overline{\lambda }}_{N}\) is revised IC of TN, and \({\overline{\lambda }}_{P}\) is improved IC of TP. \({L}_{i}\) denotes the total pollutant inflow (kg), where \(i\) refers to either TN or TP. \({A}_{j}\) represents area of the \({j}^{th}\) land use within the watershed (km2), and \({E}_{ij}\) is the EC of pollutant \(i\) for the \({j}^{th}\) land use type (kg km−2 a−1).

The model demonstrates high spatial adaptability, enabling its effective application across different basins and topographical conditions refined spatial unit division. The integration of the GA and LHS enhances both computational efficiency and model accuracy, making it capable of accounting for the complex distribution and dynamic variations of pollution sources within the watershed. While the current model estimates NPSP based on annual statistical data for population and livestock off-take, without considering the seasonal characteristics of NPSP. Future research could extend it to calculate pollution loads on a quarterly or monthly basis, providing a more precise capture of seasonal variations in pollutant emissions.

Improved export instream coefficient model

Export coefficient model optimized by genetic algorithm

The surface runoff was separated from the total runoff at the LK station through baseflow segmentation. Combined with the concentration of TN and TP at the station, NPSP load for the basin was calculated. The non-point sources included urban and rural population, livestock and poultry (including livestock, sheep, pigs and poultry) and seven land use types. The formula for total pollutants is as follows.

Here, \({L}_{i}\) represents the annual load of pollutant \(i\) (kg), \({L}_{PS}\) is the annual point source pollution load (kg), \({L}_{i0}\) represents the annual load of pollutant \(i\) arising from rural and urban population and livestock farming (kg), \({E}_{ij}\) is the EC of pollutant \(i\) for the \({j}^{th}\) type of land use (kg km−2 a−1), \({A}_{j}\) is area of the \({j}^{th}\) land use type (km2), and \(p\) signifies the nutrient ingress from precipitation (kg), which is relatively small and will be ignored.

The basin was divided into nine sub-basins (TNH, XHY, NYGL, SHHK, WJZX, LM, TG, XY and LK), with land use classified into seven categories: paddy fields, dry land, forest land, grassland, urban land, rural settlements and others. Due to the limited spatial extent of paddy fields, they were consolidated with dry land, hence nested watershed is nine and land use types is six. Subsequently, A six-element, first-order export coefficient equation (Eq. 2) was then developed to determine the ECs for each land use within the nested watersheds, optimized using LHS and GA41.

Here, \(n\) is types of land use, \(m\) represents nested watershed, \({C}_{it}\) represents the annual average concentration of the \({i}^{th}\) pollutant in the \({t}^{th}\) watershed (kg m⁻3), \({Q}_{t}\) translates to the annual runoff of the \({t}^{th}\) nested watershed (m3), \({k}_{it}\) represents loss coefficient (dimensionless) of the \({i}^{th}\) pollutant in the \({t}^{th}\) nested watershed. \({C}_{idt}\) denotes the average monitored concentration of the \({i}^{th}\) pollutant at outlet of the \({t}^{th}\) nested watershed during dry season (kg m⁻3), \({Q}_{dt}\) stands for the total flow at the outlet of the \({t}^{th}\) nested watershed during dry season (m3), and \({D}_{dt}\) is the duration of the dry season in the \({t}^{th}\) nested watershed, d.

Export instream coefficient model

-

(1)

Improved export coefficient

The greater the runoff capacity or soil moisture infiltration capacity of a watershed spatial unit, the smaller its landscape interception capacity, leading to a more significant impact on the watershed’s water body. The proportion of the normalized values of surface runoff factor (RI) and soil water leaching (LI) (Norm (RI + LI)) to the landscape interception factor (LII) was used as a correction factor (Eq. 3) of \({L}_{N}\) to calibrate the ECs of TN pollution sources in different spatial units42, and to calculate the TN discharge of agricultural NPSP. Similarly, the ratio of the normalized values (Norm (RI + K)) of surface runoff (RI) and soil erosion factor (K)43 to landscape interception capacity was used as a correction factor (Eq. 4) of \({L}_{P}\).

-

(2)

Improved instream coefficient

The rainfall erosion factor (α)44, topographic impact factor (β)45, and cost-distance factor (δ) (Eq. 7) are positively correlated with pollutant quantities. In contrast, the vegetation coverage factor (f)46 is negatively correlated with pollutants amount. Consequently, for different land use types, the product of the rainfall erosivity factor (α) and the topographic impact factor (β) is used in proportion to the product of the cost-distance factor (δ) and the vegetation coverage factor (f) as the correction factor for pollutant quantities \(\overline{{\lambda_{N} }}\) and \(\overline{{\lambda_{P} }}\).

where, \({\lambda }_{N}\) and \({\lambda }_{p}\) represent the improved IC of TN and TP, \(\overline{{\lambda_{N} }}\) and \(\overline{{\lambda_{P} }}\) represents the empirical value of IC, with 0.3 assigned for TN and 0.2 for TP.

The cost-distance coefficient (δ), based on the river distance coefficient47, pollutant production factor (CI), slope factor (S) and slope length factor (L) were reclassified, and the results were logarithmically transformed to construct it.

where \(C{I}^{\prime},\) \({S}^{\prime}\) and \({L}^{\prime}\) represent the reclassified results of each factor, \({\alpha }^{\prime}\) is accumulated flow parameter at a certain point within watershed, \(\theta\) and \(\lambda\) represent the slope and slope length extracted from DEM, respectively, \(m\) is the slope length index that fluctuates with variations in slope \(\theta\).

Combining the improved EC and IC, the enhanced EC-ICM for TN and TP is as follows.

where \({L}_{N}\) and \({L}_{P}\) illustrate the amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus pollutants entering the river, while \({EC}_{N}\) and \({EC}_{P}\) illustrate the EC of traditional ECM.

Relative error

Actual pollutant concentration data (C, mg/L) and the monthly average runoff (Q, m3) were used to estimate pollutant flux at LK hydrological station. The relative error (Re, %), between observed pollutant flux \(({L}_{0})\) and model-simulated flux (L) was calculated to verify the accuracy of the EC-ICM.

Entropy weight method

The Entropy Weight Method (EWM) is commonly applied in watershed management and pollution control to minimize subjective bias in assigning weights to indicators48. This method aims to determine the weights of TN and TP based on pollutant loads. The steps involved in EWM are as follows:

-

(1)

Selection of evaluation factors.

Characteristic factors of TN and TP pollution are identified for each sub-basin, and a decision matrix is constructed for different sub-basins. The matrix \(A=({a}_{ij}{)}_{n\times m}\), where \({a}_{ij}\) represents the \({j}^{th}\) pollutant of the \({i}^{th}\) sub-basin; \(n\) is the number of countries; \(m\) is the number of evaluation factors.

-

(2)

Decision matrix standardization.

The decision matrix \(A\) is normalized using the extreme difference normalization method to mitigate the impact of varying physical magnitudes among the indicators.

For positive indicators:

For negative indicators:

Standardized decision matrix \(A\):

-

(3)

Calculating the normalized matrix

$$\hat{R} = \left( {r_{ij} } \right)_{n \times m}$$(18)$$\hat{r}_{ij} = \frac{{r_{ij} }}{{\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {r_{ij} } }}\;$$(19) -

(4)

Calculating the information entropy of each attribute factor

$$E_{j} = - \frac{{1}}{{{\text{ln}}n}}\sum \hat{r}_{ij} {\text{ln}}\hat{r}_{ij}$$(20)

When \(\hat{r}\) = 0, \(\hat{r}\ln \hat{r}\) = 0 is specified.

-

(5)

Calculating the attribute weight vector

$$w = \left( {w_{1} ,w_{2} , \cdots ,w_{m} } \right)$$(21)

where,

The risk index of nitrogen and phosphorus NPSP was derived through raster overlay, with risk levels categorized into four classes using the natural breaks (Jenks) method. The formula for calculating TN and TP agricultural NPSP risk index is:

where, \(TNANSP\) represents the nitrogen and phosphorus NPSP risk index, \({W}_{m}\) is the weight of the \({m}^{\text{th}}\) evaluation factor, and \({I}_{m}\) are assigned level values of each evaluation factor.

Results

ECM and EC-ICM comparison

Relative error result of export coefficients

LHS is adopted to initialize the ECs as population for GA optimization in nested sub-basins. The determination of ECs is based on literature reviews9 as shown in Table 3. The reference ranges for TN in cultivated lands, forests, grasslands, urban areas, rural resident locations, and other land use types for TN are set as (0, 350), (90, 150), (210, 400), (195, 350), (195, 300) and (150, 500), respectively, while for TP, the ranges are (6.0, 20), (0.5, 5.0), (1, 10), (3.5, 15), (3.0, 15) and (3.0, 15). The units of these coefficients are t/km2. A population size of 4000 is chosen, with 2000 iterations and a maximum of 200 steps. The optional ranges for the crossover and mutation rates are set to (0.5, 0.9) and (0.1, 0.6), respectively. After optimization using GA, the initial ECs for different land use types are refined in Table 4, and the optimized objective function (Re) is presented in Table 5. The relative error of TN ECs calculated using GA in KNH, XHY, BYGL, TG, XY and LK watershed (Fig. 2) are 31.58%, 48.50%, 27.51%, 20.22%, 43.19% and 18.55% , respectively, while for TP ECs, the relative errors are 16.28%, 5.41%, 10.65%, 2.93%, 24.80%, 6.92%. At the LK hydrological station, the relative error is within 20%, indicating that the initial EC results are reliable. The relative error obtained using the EC-ICM is even smaller, demonstrating greater accuracy. The observed TN and TP loads at the LK station were 72,739.01 t and 920.53 t, respectively. The improved EC-ICM simulated TN and TP loads of 63,194.42 t and 918.37 t, with relative error of 6.92% and 0.23% respectively. This represents a significant improvement over the GA-based nested basin approach, which estimated TN and TP loads approximated at 59,244.77 t and 860.97 t respectively, with relative errors of 18.55% and 13.12%. The reduction in relative error demonstrates the strong spatial variability and accuracy of the EC-ICM, which accounts for critical impact factors such as rainfall runoff (RI), soil water leaching (LI), landscape interception (LII), soil erosion factor (K), topographic influence factor (β), rainfall erosivity factor (α) and vegetation cover factor (f). The ECs selected by the model are reasonable and reliable, fully meeting the output requirements. The EC-ICM could be extended to large-scale watershed with limited data availability, based on initial ranges of different land use types, to accurately estimate the TN and TP discharges.

Spatial distribution of improved export instream coefficient

The initial ECs for different land use types, showed in Fig. 3a,b, were derived from the GA-optimized six-element first-order export coefficient equation set. These ECs exhibit minimal spatial variability, as they are based solely on land use types. Grasslands, which cover 48.47% of the basin area, had initial ECs at 233.40 kg km−2 a−1 for TN and 5.90 kg km−2 a−1 for TP. Cropland, the second-largest land use type, occupied 24.68% of the basin and had initial ECs of 332.23 kg km−2 a−1 for TN and 5.90 kg km−2 a−1 for TP. Forestland, covering 13.33% of the basin, had ECs of 166.63 kg km−2 a−1 for TN and 1.75 kg km−2 a−1 for TP.

Spatial distribution ECs and ICs of TN and TP (a: initial EC of TN; b: initial EC of TP; c: improved EC of TN; d: improved EC of TP; e: improved IC of TN; f: improved IC of TP) (Fig. 3. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

The improved EC-ICM demonstrates significantly greater spatial variability compared to the initial ECs. The bar chart in the top-left corner of Fig. 3c shows that the initial ECs for TN primarily range from 0 to 3.58, with a maximum of 4.27, a minimum of 0, and an average of 1.00. The annual average intensity of water and wind erosion is relatively high in hilly and gully areas54, and different types of landscape vegetation effective intercept, retain and degrade NPSP entering water bodies55. Consequently, the ECs for TN increase from northwest to southeast, with higher concentrations observed in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, including the Longyangxia to Lanzhou main stream area, Daxia River, and Taohe River regions, as well as in the Guanzhong Basin, Fenhe Valley, and the lower reaches of the river. High EC values are predominantly found in the upper reaches of the Yellow River and the middle reaches of the Guanzhong Basin and Fenhe Valley, areas significantly influenced by rainfall erosion4.

Figure 3d reveals that ECs for TP are more evenly distributed across the basin, generally ranging from 0 to 1.70, with a maximum of 5.46, a minimum of 0, and an average of 0.7. This distribution shows little spatial variability across the basin56. The improved ICs for both TN and TP (Fig. 3e,f) ranged from 0 to 4.1, with maximum and average values of 23.94 and 1.00, respectively. The improved ICs, which incorporate factors rainfall such as erosion factor (α), topography factor (β), vegetation cover factor (f) and cost-distance factor (δ), are more effective at reflecting spatial differences in pollutant generation compared to traditional models57. ICs are significantly influenced by terrain and vegetation cover, with areas of greater terrain undulation or slope exhibiting more intense erosion. Therefore, high ICs are concentrated in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, from Longyangxia to Lanzhou, as well as in the Guanzhong Plain and Central Plains urban agglomerations58.

Contribution of three pollution sources to non-point source pollution load

Pollutant discharge from different land use types

Figure 4a,c present the EC-IC coefficient of TN and TP across seven land use types after applying the EC-ICM. This model incorporates spatial variability in the EC and accounts for the increased erosion associated with greater topographic relief, which impacts the IC. The EC-IC coefficients exhibit significant spatial variation, with higher values primarily observed in the Jing River and Wei River control areas in the middle reaches, as well as in the North China Plain in the lower reaches.

Spatial distribution of improved EC-ICM for seven land use types (a: EC-IC_TN; c: EC-IC_TP) and riverine pollutant load of agricultural NPSP in sub-basins (b: TN; d: TP) (Fig. 4. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

Grassland, cropland, and forestland dominate the land use types, covering 48.47%, 24.68%, and 13.22% of the area, respectively, totaling 86.37% of the YRB. Urban land and rural settlements comprise a smaller proportion, accounting for only 2.80%, while other land use types represent less than 10.85%. Figure 4b,d illustrate the distribution of river-entry TN and TP loads at the county scale. From a land use perspective, grassland is the largest contributor to pollution, generating 24,203.81 t of TN and 327.73 t of TP, accounting for 46.70% and 54.10% of the overall TN and TP loads entering the river. Cropland is the second largest source, contributing 38.19% of TN and 31.12% of TP. Forestland, known for its capacity to dilute TN, dissolved phosphorus, and larger particulate contaminants59, accounts for 4.36% of total pollution entering the river. Rural settlements contribute approximately twice as much to pollution as urban land, with TN contribution rates of 2.24% and 1.45%, respectively, and TP contribution rates of 0.91% and 0.51%. In conclusion, while all land use types influence NPSP, to varying degrees, grassland and cropland are the primary sources of land use-related pollution17. Forestland, with the lowest EC and IC values, suggests that reforestation and land reclamation could effectively reduce pollutant discharge into water bodies60.

Riverine pollutant load from urban and rural population

County-level population data from nine provinces in the Yellow River Basin (Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, and Shandong) were combined with the ECs and ICs for urban and rural residents (Table 1) to estimate TN and TP loads from the urban and rural populations in the basin (Fig. 5). As urbanization increases, the national urbanization rate has reached 66.16%, with the rural population now slightly trailing the urban population. The trends in both populations are similar. The average annual urban population was approximately 49.83 million in the basin, while the rural population averaged 69.40 million. A significant proportion of the population is concentrated in the middle and lower reaches, particularly in the SHHK and TG sub-basins. The population in the sub-basins controlled by TG, LK and XHY decreased successively, with urban and rural populations of 21.99 and 17.87 million, 17.19 and 11.81 million, and 8.93 and 5.25 million, respectively. The TNH sub-basin, located at the Yellow River source, had the smallest population, with only 0.17 million urban and 0.34 million rural residents. In other sub-watershed areas, urban populations ranged between 1.00 and 5.30 million, while rural populations ranged from 0.60 to 6.40 million.

Spatial distribution of urban and rural population and pollutant emissions (a: urban population; d: rural population; c: urban population TN emissions; d: rural population TN emissions; e: urban population TP emissions; f: rural population TP emissions; The lower left corner of each figure is the value of the indicator in nine sub-basin counties, and the lower right corner is the probability density distribution of the indicator, g: nine sub-basin in yellow river). (Fig. 5. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

The TN riverine pollutant load generated by the rural and urban population was 9.90 times that of TP, with the urban population contributing more to nitrogen and phosphorus pollution than the rural population. Spatially, emissions were primarily concentrated in the middle and lower reaches, especially in economically advanced areas such as the TG, LK, and XHY sub-basins. In the TG sub-basin, the urban population discharged 54,527.43 t of TN and 5496.72 t of TP, while the rural population contributed 82,764.07 t of TN and 8356.12 t of TP, accounting for 31.68% and 35.87% of total TN and TP emissions, respectively. Urban emissions amounted to 42,630.27 t of TN and 4297.41 t of TP, while rural emissions accounted for 18,665.24 t of TN and 1890.15 t of TP, contributing 24.77% and 23.71% of TN and TP, respectively. In the XHY sub-basin, urban emissions were 22,167.90 t of TN and 2234.67 t of TP, while rural emissions were 8287.09 t of TN and 839.20 t of TP.

Although the population in the TNH and SHHK sub-basins was small, the population probability density was higher (Fig. 5a), contributed less than 2% of TN and TP emissions. In other sub-basins such as LM, XY, WJZX, and BYGL, urban and rural populations discharged TN at 18,489.59 t, 22,578.66 t, 14,437.20 t and 16,313.12 t, respectively, and TP at 1867.03 t, 2280.68 t, 1456.19 t and 1646.00 t. At the county level, the highest TN and TP emissions from urban populations were observed in Chengguan District, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, with total emissions of 3656.56 t and 368.65 t, respectively. The lowest emissions were recorded in Qihe County, Dezhou, Shandong Province, with TN and TP emissions of 0.65 t and 0.07 t, respectively.

Riverine pollutant load from livestock and poultry farming

Based on livestock and poultry off-take statistics and ECs for 2021 to 2023 from the nine provinces, a distribution of TN and TP pollutants emissions was generated, as shown in Fig. 6. These statistics include the number of large livestock, sheep, pigs and poultry. Poultry had the highest annual off-take, averaging 6.337 billion birds. Sheep and pigs followed, with averages of 57.09 million and 35.66 million, respectively. Large livestock had the lowest off-take, averaging 6.30 million. Despite the smaller off-take of large livestock, their higher ECs for TN61, 3.23, 1.74, and 32.27 times higher than those of sheep, pigs, and poultry, respectively—resulted in a greater contribution to pollution. The average annual TP discharge from large livestock was 1385.76 t, 5.56 times that of poultry but smaller than the discharge from sheep and pigs, which averaged 2242.35 t and 6976.20 t, respectively.

Livestock and poultry off-take and TN and TP emissions (a1, a2, a3 show large livestock off-take, total nitrogen and total phosphorus emissions; b1, b2, b3 show sheep off-take, TN and TP emissions; c1, c2, c3 show poultry off-take, TN and TP emissions; d1, d2, d3 show pig off-take, TN and TP emissions). (Fig. 6. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

At the sub-basin level, the distribution patterns of large livestock and sheep off-take were quite similar, with standard deviations of 0.07 and 0.06, respectively. The XHY sub-basin had the highest off-take, with 1.54 large livestock and 11.04 million head sheep, contributing 24.47% to the TN discharge. The BYGL sub-basin followed with 7.82 million sheep and 0.99 million large livestock, contributing 14.96% to TP emissions. Combined, emissions from livestock and poultry in the XHY and BYGL sub-basins accounted for 33.20% of basin’s TN or TP emissions. Excluding the TNH and XY sub-basins, sheep off-take in other sub-basins fluctuated between 5.10 and 11.00 million, with an annual average TN emission from sheep 8.89 times higher than TP emissions. Pig off-take showed greater variation, with a standard deviation of 0.12. The LK sub-basin recorded the highest pig off-take, with 12.96 million pigs, contributing 36.33% to the basin’s total emissions. The TG sub-basin had an average annual off-take of 9.97 million pigs, contributing 27.97% to the total emissions. In the TNH sub-basin, contributions from pigs and poultry were negligible, accounting for only 0.3% of the basin’s emissions. In contrast, pig contributions in other sub-basins ranged from 2.80 to 9.10%. Poultry off-take was the most heterogeneous across sub-basins, with a standard deviation of 0.19. The LK sub-basin had the highest off-take, with 373.39 million birds, accounting for 58.92% of the basin’s total, followed by the TG sub-basin at 23.00%.

In summary, large livestock and sheep in the LK and TG sub-basins contributed significantly to pollutant emissions, accounting for 40.20% and 45.34%, respectively. The highest contributions from pigs and poultry to TN and TP emissions were observed in the TG and BYGL sub-basins, accounting for 64.30% and 81.92%, respectively.

Accounting of three types of non-point source river-entry loads

TN and TP pollutants discharged into rivers from urban populations are significantly higher than those from rural populations. The riverine loads of TN and TP pollutants show a nearly symmetrical distribution across different sub-watersheds (Fig. 7a). In sub-basins with extensive cropland and high population density, urban in the TG sub-basin contributed 8595 t of TP and 5452.74 t of TN, accounting for 33.00% of the total contribution from the population. In the LK sub-basin, urban residents contributed 109.93 t of TP and 4263.03 t of TN, representing 24.44% of total contribution. Livestock and poultry farming contributed 316.75 t of TP and 20,146.31 t of TN to the riverine loads (Fig. 7b). Among the sub-watersheds, TG and LK made the largest contributions, with respective rates of 33.29% and 15.80%. In terms of livestock types, the contribution order is pigs > sheep > large livestock > poultry, with respective contribution rates of 64.28%, 20.66%, 12.77%, and 2.30% across the entire watershed. For TN, the order shifts to large livestock > pigs > sheep > poultry (52.24% > 29.95% > 16.19% > 1.62%), whereas for TP, it is pigs > sheep > large livestock > poultry (63.85% > 11.06% > 20.52% > 2.28%). In the TG sub-basin, TN loads from large livestock, pigs, sheep, and poultry are 2023.00 t, 1429.70 t, 2644.95 t and 142.97 t, respectively, with corresponding TP loads of 43.59 t, 160.84 t, 500.40 t and 17.87 t. As shown in Fig. 7c, the contribution of livestock and poultry farming to TN and TP riverine loads exceeds that of the population.

Figure 7d presents TN and TP loads entering rivers from different land-use types, clearly indicating that grasslands and croplands are the primary contributors. Sub-basins controlled by TG, LK, TNH, and XHY exhibit the highest pollutant loads, with TN riverine pollutant load of 13,458.62 t, 9602.95 t, 9472.36 t and 8019.73 t, respectively, and TP riverine pollutant load of 99.93 t, 56.82 t, 102.15 t and 94.88 t, respectively. Notably, although the XY and TNH have relatively low pollutant emissions from population and livestock activities, the pollutant loads entering rivers from land use remain high. This is mainly due to the large grassland and cropland areas in these regions: grasslands in the TNH sub-basin comprise 12.32% of the total area of the YRB, while grasslands and croplands in the XY sub-basin account for 10.27% and 2.92%, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7e, the TN loads entering rivers across the sub-basins, ranked from highest to lowest, are TG, LK, XHY, LM, XY, BYGL, WJZX and SHHK. The total TN load in the YRB amounts to 86,416.15 t, with 56,777.24 t, (65.70%) derived from land use. For TP pollution, the ranking of sub-basins is TG, LK, XHY, LM, BYGL, TNH, WJZX, and SHHK (Fig. 7f). The total TP discharge is 3291.93 t, primarily originating from livestock and poultry farming. Contributions of TN from land use, population, and livestock and poultry are 65.70%, 5.81% and 28.49%, respectively, while contributions of TP are 18.68%, 15.38% and 65.94%, respectively.

In summary, cropland, grassland, population, and livestock farming activities in the YRB contribute to NPSP to varying extents. Land use is the primary source of TN entering the river, with grassland and cropland as the main contributors, accounting for 42.63% and 38.19% of TN, respectively17. Forestland, with the lowest EC and IC values, benefits from land reclamation and afforestation, which are recommended to reduce pollutant discharge into water bodies60. C In contrast to TN, TP loads entering the river are substantially lower, with livestock farming being the major contributor, accounting for 65.94% of the basin’s TP load. The adoption of an integrated livestock-crop management model, combining livestock breeding with crop cultivation, can promote the organic recycling of manure and nutrients, thus reducing environmental pollution risks.

Risk assessment and identification of priority control area

The YRB was selected as the study area to assess TN and TP NPSP risks for 2021–2023. The EWM was applied to calculate the weights of rainfall erosion (γ), slope (θ), soil erodibility factor (K), soil cover management factor (C), annual vegetation coverage (FVC), and soil and water conservation factor (P) (Fig. 8). The weights of TN and TP riverine strength were determined to be 0.35. Details of the weights and grading assignments for each evaluation factor are provided in Table 3.

Spatial distribution of Non-point source pollution influencing factors. (Fig. 8. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

The pollutant source intensity for each county in the nine provinces was calculated based on river-entry loads from land use, livestock farming, and population (Fig. 8a,b). The natural breaks method was used to classify TN NPSP risk index into four categories: no risk (risk index 1.38–2.08), low risk (risk index 2.08–2.36), medium risk (risk index 2.36–2.59) and high risk (risk index 2.59–3.49). High-risk areas for TN NPSP covered 100,400 km2, accounting for 12.32% of the basin. Medium-risk areas spanned 284,700 km2, representing 34.92% of the basin. Low-risk and no-risk areas covered 296,800 km2 and 133,600 km2, constituting 36.41% and 16.36% of the basin, respectively. The TN pollution risk levels indicated minimal variation along the river course, with the majority classified as low to medium-risk (Fig. 9). However, the TG and XHY sub-basins contained a higher number of high-risk counties. The Loess Plateau in Longdong, which includes Guyuan, Pingliang, and Qingyang in Gansu Province, along with Xianyang and Xi’an in Shaanxi Province, poses significant NPSP risks58,62. Grasslands, as a widely distributed pollutant source, contribute significantly to soil erosion in the Gannan region. The central and eastern Gansu agricultural regions experience the most severe erosion63, with livestock and domestic sources significantly impacting these areas. Medium-risk zones are primarily located in regions including Baiyin, Lanzhou, Dingxi and Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu Province, as well as the downstream Yellow River areas, the Loess Plateau in Shaanxi, and the southern Guanzhong Plain urban agglomeration. Terrain significantly influences rainwater collection and river flow in regions such as the Qilian Mountains in the northwestern region and the Helan Mountains in the north64. The resulting high ICs and pronounced soil erosion elevate risk levels in these areas. Low-risk areas are predominantly found in the Yellow River source region, most of Qinghai Province, Inner Mongolia, much of Shanxi Province, and the downstream urban agglomeration65. These regions are characterized by a scarcity of grasslands and farmlands, with forests as the dominant landscape. Although cropland is extensive in the downstream regions, high vegetation coverage in the downstream croplands of the Yellow River effectively intercepts pollutants, thereby lowering the overall risk level. Areas such as the Ordos Plateau in Inner Mongolia and the northern reaches of Yulin in Shaanxi, with flat terrain, low population densities, and minimal livestock off-take, are classified as no-risk zones. Similarly, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan, with low population densities and limited livestock activity, are also categorized as no-risk zones.

Risk levels of TN (a) and TP (b) non-point source pollution and risk index changes along the Yellow River of TN (c) and TP (d) (Fig. 9. Homemade maps, production software: ArcGIS 10.5 https://www.esri.co).

According to Natural Breaks method, TN and TP NPSP are divided into four categories. The classification standards for TP NPSP risk index are as follows: no risk (risk index 1.32–2.01), low risk (risk index 2.01–2.23), medium risk (risk index 2.23–2.50) and high risk (risk index 2.50–3.35). High-risk areas encompass 95,300 km2, making up 11.69% of the total basin. Medium-risk regions span 286,300 km2, representing to 35.11% of the basin area. Low and no-risk areas comprise 252,400 km2 and 181,300 km2 respectively, making up 30.97% and 22.23% of the basin. The high-risk zones are primarily located in the Loess Plateau and gully regions of Guyuan and Pingliang in Gansu Province, where significant soil erosion on farmland and medium-cover grassland is evident63. Other high-risk areas include Zhongwei in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Longdong. Medium-risk areas are mainly found on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, in Qingyang in Gansu Province, and in the southern Shaanxi urban agglomeration on the Guanzhong Plain, where steep slopes exacerbate erosion risks. Low-risk and no-risk areas are predominantly located in the middle and lower reaches of the YRB. The distribution patterns of TP and TN pollution levels are highly similar, with minimal variation along the river course. Most areas fall within low to medium-risk categories (Fig. 9). However, NPSP risks are notably higher in the TNH and TG sub-basins. The Gannan Yellow River water supply region, a climate-sensitive and ecologically fragile alpine area, experiences substantial environmental damage due to grassland degradation, with significant contributions from livestock and domestic sources. Medium-risk areas are concentrated on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, where varied terrain, steep slopes and meadow vegetation degradation have intensified soil erosion and worsened soil physical and chemical properties66. Other medium-risk regions include Qingyang in Gansu, Baoji and Ankang in Shaanxi, and parts of the financially prosperous and densely populated Guanzhong Plain urban agglomeration, where high vegetation cover helps mitigate pollutant loss. Due to the above seasonal characteristics, NPSP in the YRB reaches its peak in summer, and there is also a high risk of pollution input due to agricultural fertilization in spring and autumn. Therefore, when estimating and managing pollutants, it is necessary to fully consider these temporal and spatial variation characteristics to improve the pertinence of pollution prevention and control measures. Low-risk areas are primarily located in Baiyin, Lanzhou, the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu, northern Yan’an and Yulin in Shaanxi, Changzhi and Jincheng in Shanxi, and Sanmenxia in Henan. These areas exhibit low TP NPSP intensity, with forests dominating the landscape. Although cropland is extensive downstream of the Yellow River, high vegetation cover effectively intercepts pollutants, resulting in overall low-risk levels67. Low-pollution zones also include the Ordos Plateau in Inner Mongolia, the central region of China’s farming-pastoral transition zone experiencing a dry climate and high evaporation rates, while the flat terrain and slow water flow restrict surface runoff from exiting the region68.

Discussion

An improved Export Coefficient and In-stream Coefficient Model (EC-ICM) for estimating NPSP loads in large watersheds is introduced by refining ECs and ICs. Building on previous research on ECs (Table 3), initial estimates were established for land-use types. GA was employed to identify the optimal ECs by minimizing relative errors, followed by the introduction of correction factors based on these optimized ECs. The improved model significantly reduced the relative errors in the NPSP loads entering rivers in large watersheds, with relative errors for TN and TP decreasing by 11.63% and 12.89%, respectively. The results indicate that the improved model can more accurately capture the spatial variation of NPSP within the watershed, particularly enhancing its adaptability and accuracy when dealing with complex terrain and climatic conditions. Additionally, the entropy weight method was used to categorize the pollution risk in the Yellow River Basin into four levels, with region-specific pollution control measures applied to each level, further supporting watershed pollution management. It strengthens the spatial distribution differences of the export and in-stream coefficients, optimizing its performance under complex topographical and precipitation conditions. Therefore, EC-ICM provides effective theoretical support for watershed pollution monitoring and demonstrates strong applicability, especially in the management of pollution in large watersheds.

Rainfall-runoff processes have previously been integrated into WEC to estimate the contribution of different land-use types to TN and TP loads69. Building on these efforts, multiple factors-such as precipitation, terrain influence, and landscape interception—are incorporated, and GA is employed to optimize ECs, enhancing the model’s adaptability across diverse sub-basin conditions. Significant spatial heterogeneity in pollution ECs is observed within the YRB4, especially in regions like Longyangxia in the upper reaches and the Guanzhong Plain in the middle reaches, where high rainfall intensity and complex topography contribute to elevated nitrogen and phosphorus loads. To further refine the spatial distribution of pollution loads, slope (β) and vegetation coverage (f) are incorporated, improving the model’s adaptability across sub-basins. By optimizing spatial heterogeneity analysis and incorporating multiple environmental driving factors, the accuracy of pollution load predictions was improved, while a theoretical foundation for watershed pollution management was also provided.

Additionally, landscape interception indices (LII)4, soil erosion factors (K)43, and rainfall erosion factors (α)44 are integrated, enriching the understanding of how landscape structures influence pollution control and quantifying the contribution of various factors to watershed management. The result indicates that topography and vegetation cover have a significant impact on the output of NPSP. To further optimize the model and better account for spatial and ecological differences, the cost-distance coefficient (δ) is introduced for the first time. The inclusion of the factor enhances the model’s ability to capture spatial variability, particularly in the distribution of pollution sources and differences in watershed management across regions. Although the spatial distribution of TP outputs across the YRB is relatively uniform, EC-ICM detects local variations in TP coefficients caused by terrain and rainfall conditions in the upper and middle reaches, enabling more targeted pollution control strategies. By combining ECs and ICs within a distributed model structure, the model improves on centralized approaches4 by effectively accounting for the impact of spatial heterogeneity on ECs. As a result, it offers more precision in predicting pollution outputs and better accommodates complex terrain conditions.

Grassland and cropland are the primary contributors to TN and TP pollution in the YRB, accounting for 42.63% and 38.19% of the total pollution, respectively. Agriculture and grassland degradation have been identified as major drivers of NPSP in the region70. Cropland soils are often left exposed, and frequent agricultural activities weaken soil structure, increasing the risks of runoff and erosion. Nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers are easily lost through runoff during heavy rain, leading to the eutrophication of water bodies71. Although grasslands, with better vegetation cover and root systems, provide stronger erosion control than cropland, overgrazing or concentrated seasonal rainfall can damage topsoil, resulting in erosion and nutrient loss72. In contrast, forests demonstrate superior abilities to intercept sediment and pollutants due to dense vegetation cover, stable soil structures, and deep root systems. Forest floors, with layers of litter, absorb rainfall and reduce both runoff and soil particle loss, making them effective in controlling NPSP71. The results provide a foundational basis for agricultural and ecological management within the watershed and emphasize the urgent need for ecological restoration, particularly in regions severely impacted by agricultural and grassland degradation.

Differentiated pollution control strategies are proposed for different risk levels. Specifically, strict pollution source control will be implemented in high-risk areas, with an emphasis on utilizing forested areas for ecological restoration and soil and water conservation73. Key strategies include converting farmland to forests71, vegetation restoration74, and afforestation75. For medium-risk and low-risk areas, ecological agriculture and crop rotation are recommended to reduce pollutant loads. Particularly in the Zhongyuan and Guanzhong Plain urban agglomerations, the concentration of population exacerbates pollution in the middle and lower reaches of the watershed, while the dominant role of livestock farming in TP pollution highlights the critical importance of integrating livestock and crop management systems to reduce pollution risks. The combination of pollution risk zoning and regional governance strategies provides differentiated management solutions for watershed pollution and offers actionable strategic recommendations for future water quality protection and ecological restoration practices.

Although EC-ICM comprehensively considers factors such as topography, rainfall, soil properties, and cost distance, it remains limited in its ability to simulate critical processes, including pollutant migration, deposition, resuspension, and degradation in river systems. In low-flow areas, pollutants may be reduced through deposition, whereas in high-velocity zones, sediment resuspension can result in the secondary release of pollutants. These processes significantly influence the temporal and spatial distribution of pollutants76. However, they are not yet fully incorporated into the current model. To address this, the integration of hydrodynamic models could enhance the simulation of pollutant transport and transformation processes77,78, thereby improving the prediction of spatiotemporal variations in pollutant concentrations. Furthermore, the emission and transport of NPSP exhibit strong seasonal characteristics. During the flood season, precipitation-driven runoff substantially increases pollutant export, while in the dry season, reduced water volume may lead to relatively higher pollutant concentrations79. The concurrence of agricultural fertilization and rainfall further exacerbates pollutant loss5. Annual data were used for estimation, which effectively represents long-term pollution load trends; however, it fails to capture short-term variability. This limitation in temporal resolution may result in underestimation of pollutant loads during high-pollution seasons and overestimation during dry periods, thereby affecting the accuracy of pollution contribution rates in certain sub-basins. Incorporating monthly or seasonal data could improve the model’s temporal resolution, enhancing its capacity to reflect pollutant dynamics under seasonal variation. Additionally, climate change may substantially alter precipitation patterns, rainfall intensity, and temperature, thereby influencing the transport, transformation, and distribution of pollutants. The integration of real-time monitoring data with dynamic climate projections could support the simulation of non-point source pollution trends under various climate scenarios. This approach would enhance model applicability and accuracy, enabling more effective evaluation of climate change impacts on basin-scale water quality management.

Conclusions

Addressing the challenges in accurately estimating NPSP within the Yellow River Basin required the development of the EC-ICM framework, integrating economic, hydrological, and meteorological data from 2021 to 2023. Validation against genetic algorithm-optimized model confirmed improvements in model robustness for large-scale applications. By integrating urban and rural populations with livestock farming, pollutant discharge and riverine input of nitrogen and phosphorus are estimated at the sub-watershed and county scales. Additionally, risk assessments for TN and TP are conducted. The following conclusions were drawn.

-

(1)

The EC-ICM incorporates factors such as rainfall erosivity, slope, topography, vegetation cover, pollutant production, and cost-distance and reduces the relative errors in TN by 5.43% and TP by 6.69% in land use types. It significantly enhances the accuracy of estimating the riverine input of watershed NPSP, providing a more precise and applicable model for simulating NPSP in large watersheds.

-

(2)

Land use contributes 65.70% of TN loads, followed by population (5.81%) and livestock farming (28.49%). For TP, livestock farming accounts for the highest contribution (65.94%), with land use and population contributing 18.68% and 15.38%, respectively.

-

(3)

The Longdong Loess Plateau in eastern Gansu, identified as a high-risk area, contributes approximately 12% of the basin’s total pollution. The regional management strategies based on pollution risk zoning emphasize the importance of prioritizing high-risk areas.

-

(4)

Future research should further incorporate climate change scenarios and seasonal variability to enhance the model’s capability in predicting NPSP dynamics. Seasonal factors, such as increased runoff during the wet season and pollutant accumulation during the dry season, could significantly influence TN and TP transport processes. Integrating real-time monitoring data and climate projections may improve model adaptability under changing environmental conditions

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chahor, Y. et al. Evaluation of the AnnAGNPS model for predicting runoff and sediment yield in a small Mediterranean agricultural watershed in Navarre (Spain). Agric. Water Manag. 134, 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2013.11.014 (2014).

Buchanan, B. P. et al. A phosphorus index that combines critical source areas and transport pathways using a travel time approach. J. Hydrol. 486, 123–135 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 237, 15–23 (2019).

Lei, W., Li, P. & Ma, X.-y. Estimating nonpoint source pollution load using four modified export coefficient models in a large easily eroded watershed of the loess hilly–gully region, China. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5857-1 (2016).

Chen, Y. GIS-based Risk Assessment of non-point Source Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loss from Agricultural Soils in Yueyang Quyuan Management Area (Central South University of Forestry and Technology, 2024).

Han, Y. et al. Assessing non-point source pollution in an apple-dominant basin and associated best fertilizer management based on SWAT modeling. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 11(2), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2022.10.002 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Phosphorus spatial distribution and pollution risk assessment in agricultural soil around the Danjiangkou reservoir, China. Sci. Total Environ. 699, 134417 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Environmental risk assessment of phosphorus loss from farmland based on phosphorus index model in the Haihe river basin. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36 (14), 17–27 (2020).

Xue, L. Research advances of export coefficient model for non-point source pollution. Chin. J. Ecol. 28 (04), 755–761 (2009).

Yang, Y. & Yan, B. Assessment of point and nonpoint sources pollution in Songhua river basin, Northeast China by using revised water quaLity model. Chin. Geogra. Sci. 20, 30–36 (2010).

Long, T., Li, J. & Liu, L. Adsorbed non-point source pollution load of Jialing river basin. Environ. Sci. 07, 1811–1817 (2008).

Knisel, W. G. CREAMS: A field scale model for Chemicals, Runoff, and Erosion from Agricultural Management Systems [USA]. (1980).

Bouraoui, F. & Dillaha, T. A. ANSWERS-2000: Non-point-source nutrient planning model. J. Environ. Eng. 126, 1045–1055 (2000).

Gupta, A. K., Rudra, R. P., Gharabaghi, B. et al. CoBAGNPS: A toolbox for simulating water and sediment control basin, WASCoB through AGNPS model. Catena (2019).

Shen, Z. & Liao, Q. An overview of research on agricultural non-point source pollution modelLing in China. Sep. Purif. Technol. 84, 104–111 (2012).

Huang, J. et al. Modeling nitrogen export from 2539 lowland artificial watersheds in Lake Taihu Basin, China: Insights from process-based modeling. J. Hydrol. 581, 124428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124428 (2020).

Yan, R., Li, L. & Gao, J. Framework for quantifying rural NPS pollution of a humid lowland catchment in Taihu basin, Eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 688, 983–993 (2019).

Ding, X. W. et al. Development and test of the export coefficient model in the upper reach of the Yangtze river. J. Hydrol. 383(3–4), 233–244 (2010).

Ma, X. et al. Assessment and analysis of non-point source nitrogen and phosphorus loads in the three Gorges reservoir area of Hubei Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 412, 154–161 (2011).

Matias, N. Catchment phosphorous losses: An export coefficient modelLing approach with scenario analysis for water management. Water Resour. Manag. 26 (5), 1041–1064 (2012).

Worrall, F. et al. The fluvial flux of nitrate from the UK terrestrial biosphere - An estimate of national-scale in-stream nitrate loss using an export coefficient model. J. Hydrol. 414, 31–39 (2012).

Wang, W., Chen, L. & Shen, Z. Dynamic export coefficient model for evaluating the effects of environmental changes on non-point source pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 747, 141164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141164 (2020).

Noto, L. V. et al. Effects of initiaLization on response of a fully-distributed hydrologic model. J. Hydrol. 352, 107–125 (2008).

Wang, J. et al. Simulation of the dissolved nitrogen and phosphorus loads in different land uses in the three Gorges reservoir Region–based on the improved export coefficient model. Environ. Sci. Processes. 17 (11), 1976–1989 (2015).

Johnes, P. J. Evaluation and management of the impact of land use change on the nitrogen and phosphorus load delivered to surface waters: The export coefficient modelling approach. J. Hydrol. 183(3–4), 323–349 (1996).

Zou, L. et al. Assessment and analysis of agricultural non-point source pollution loads in China: 1978–2017. J. Environ. Manag. 263, 110400 (2020).

Rong, Q. & Zeng, J. Prediction and optimization of regional land-use patterns considering nonpoint-source pollution control under conditions of uncertainty. J. Environ. Manag. 306, 114432 (2022).

LiU, Y., Yang, L. & Li, F. Estimation of pollution loads from agricultural nonpoint sources in Beijing region based on export coefficient modeLing approach. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 27 (07), 7–12 (2011).

Gao, T. et al. Simulation and source analysis of nonpoint source nitrogen and phosphorus pollution export in a typical agricultural catchment draining to Chaohu Lake,China. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 41 (11), 2428–2438 (2022).

Hao, G. et al. Estimation of pollution loads from agricultural Non-point sources in the upstream of Qingshui river based on export coefficient models. Sci. Technol. Eng. 20 (33), 13919–13927 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Assessing agricultural non-point source pollution loads in typical basins of upper Yellow River by incorporating critical impacting factors. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 177, 17–28 (2023).

Khadam, I. M., Kaluarachchi, J. J. Water quaLity modeLing under hydrologic variabiLity and parameter uncertainty using erosion-scaled export coefficients. J. Hydrol. 330, 354–367 (2006).

He, Y. et al. Research on spatial characteristics and the load of agricultural non-point source pollution in Karst area of Southwestern China. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 29(01), 148–152 (2022).

Zhu, M. Study on Agricultural NPS Loads of Haihe Basin and Assessment on its Environmental Impact. (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Dissertation, 2011). Non-point source pollution load of Hongfeng Lake

Wang, M. et al. Analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution loads from agricultural non- point sources in the three Gorges reservoir of Hubei Province from 1991 to 2014. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 37 (02), 294–301 (2018).

Liu, J. An Improved Export Coefficient Model to Estimate Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loads in Pengxi River Basin. (Three Gorges Reservoir; Southwest University, 2019).

Long, T. & Liu, M. Development and appLication of non-point source pollution load model of Spatial and Temporal distribution in three Gorges reservoir region. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 32 (08), 217–223 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological vulnerability in the Yellow River Basin under ecological restoration initiatives. Ecol. Indic. 135, 108586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108586 (2022).

Xiang, X. A review on non-point source pollution models. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Agricultural Science). 31 (02), 53–60 (2013).

Borah, D. K., Bera, M. Watershed-scale hydrologic and nonpoint-source pollution models: Review of appLications. Trans. Asae. 47 (3), 789–803 (2004).

Ding, X., Liu, R. & Shen, Z. Method for obtaining parameters of export coefficient model using hydrology and water quality data and its application. J. Beijing Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 42(5), 534–538 (2006).

Pang, S. & Wang, X. AppLication of an improved model for non-point source total nitrogen output coefficient at the watershed scale. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 33 (18), 213–223 (2017).

Cai, C. et al. Study of applying USLE and geographical information system IDRISI to predict soil Erosion in small watershed. J. Soil Water Conserv. (02), 19–24 (2000).

Ding, X. et al. Improves export coefficient model considering precipitation as well as terrain and its accuracy analysis. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 02, 306–309 (2008).

Li, Z. et al. Non-point source pollution load of Hongfeng Lake reserve based on export coefficient model. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 40(02), 193–198 (2020).

Sun, W. Y. et al. Assessing the effects of land use and topography on soil erosion on the Loess Plateau in China. CATENA 121, 151–163 (2014).

Noor, H. et al. Application of MUSLE for the prediction of phosphorus losses. Water Sci. Technol. 62(4), 809–815 (2010).

Sun, T., Zhang, H. & Wang, Y. The application of information entropy in basin level water waste permits allocation in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 70, 50–54 (2013).

Zhang, H. & Jing, Y. Evolution of spatio-temporal pattern and prevention partition of TN and TP of non-point source pollution in Nansi lake basin. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 38 (02), 19–26 (2018).

Yang, W. et al. Estimation of pollution loads from rural Non-point sourcesin Qiongjiang river basin (Anju District) based on export coefficient modeLing approach. Environ. Eng. 36 (10), 140–144 (2018).

Frink, C. R. Estimating nutrient exports to estuaries. J. Environ. Qual. 20, 717–724 (1991).

Hu, F. et al. AppLied research on the improved export coefficient model in non-point source pollution in Shehong County. China Rural Water Hydropower (06), 78–82 (2019).

Feng, L. et al. Analysis on spatial-temporal characteristics and environmental Kuznets curve of non-point source pollution in the three Gorges reservoir area. China Environ. Sci. 42 (07), 3325–3333 (2022).

Tao, W. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics of soil erosion on the Chinese loess plateau and strategies for vegetation management. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. (2024).

Tang, H. et al. Removal efficiency of buffer on agricultural non-point and intensive pollution. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 28 (02), 186–190 (2012).

Han, X. et al. Identification of areas vulnerable to soil erosion and risk assessment of phosphorus transport in a typical watershed in the loess plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 758, 143661 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. An improved export coefficient model with a spatially modified river load ratio-A case study of the Yangtze River Basin. China Rural Water Hydropower 03, 78–85 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. Estimation of soil erosion and its application in assessment of the absorbed nitrogen and phosphorus load in China. Acta Sci. Circum. 03, 366–374 (2006).

Jones, K. B., Neale, A. C., Nash, M. S. et al. Predicting nutrient and sediment loadings to streams from landscape metrics: A multiple watershed study from the united States Mid-Atlantic region. Landscape Ecol. 16, 301–312 (2001).

Zhang, S., Cheng, G., Tan, Q., Zhao, H. & Zhang, T. An agro-hydrological process-based export coefficient model for estimating monthly non-point source loads in a semiarid agricultural area. J. Clean. Prod. 385, 135519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135519 (2023).

Zuo, L. et al. Progress towards sustainable intensification in China challenged by land-use change. Nat. Sustain. 1, 304–313 (2018).

Hao, F. et al. Uncertain affecting factor of the non-point source pollution load. China Environ. Sci. 03, 15–19 (2004).

Wu, L. et al. Soil erosion and its driving mechanism in tributary basins of yellow river in Gansu Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 44 (03), 221–230 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Water environmental risk assessment across different periods in the Henan section of the Wei river basin. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 42 (08), 1778–1789 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Spatio-temporal pattern and influencing factors of the coupLing coordination of new urbanization and water ecological environment in the yellow river basin. J. Desert Res. 44 (03), 172–181 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Changes in soil nitrogen stocks following vegetation restoration in a typical karst catchment. Land Degrad. Dev. 30, 60–72 (2018).

Yang, P. et al. Characteristics of spatio-temporal changes and future trends forecast of vegetation cover in the Yellow River Basin from 1990 to 2022. Acta Ecol. Sin. 19, 1–12 (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. Analysis of temporal and spatial evolution and influencing factors of soil erosion in Ordos City. Arid Zone Res. 39 (06), 1819–1831 (2022).

Liu, R. et al. Development of regional pollution export coefficients based on artificial rainfall experiments and its application in North China. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 14 (4), 823–832 (2017).

Sun, B. & Zhang, L. Agricultural non-point source pollution in China: Causes and mitigation measures. Ambio 41 (4), 370–379 (2012).

Bai, Z. et al. Effects of agricultural management practices on soil quality: A review of long-term experiments for Europe and China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 265, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.05.028 (2018).

Wu, R. Effect of land use on soil degradation in alpine grassland soil, China. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 66, 1648–1655 (2002).

Ricci, G. F., Jeong, J. et al. Effectiveness and feasibiLity of different management practices to reduce soil erosion in an agricultural watershed. Land. Use PoLicy 90, 104306 (2020).

Xie, Z. et al. The global progress on the non-point source pollution research from 2012 to 2021: A bibLiometric analysis. Environ. Sci. Eur.. 34 (1), 121 (2022).

Ricci, G. F. et al. Efficiency and feasibiLity of best management practices to reduce nutrient loads in an agricultural river basin. Agric. Water Manag. 259, 107241 (2022).

He, L. & Xiao, Z. Numerical simulation of pollutant diffusion into the Jingjiang section of the lower reaches of the Yangtze river. Yangtze River. 55 (S2), 25–32 (2024).

Huang, J., Pang, S. & Wang, X. Estimation of total phosphorus flux in river based on the change-point of concentration and flow. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 43 (03), 644–653 (2024).

Yang, Y. & Li, J. Simulation of non-point source pollution in watershed above Ankang section of the Han river based on HYPE model. Water Resour. Prot. 40 (03), 140–148 (2024).

Fu, X. Simulation of non-point source pollution and best management measures in the Guanzhong section of the Weihe River basin. (2023).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, PR China (42277073, 52070158).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xueting Wang: Conceptualization, Resources, Methodology, Visualization, Writing original draft & editing. Lei Wu: Conceptualization, Research planning, Resource coordination, Methodology, Writing’- reviewing & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Yongkun Luo: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing’—review &. editing. Yimu Liu: Methodology, Writing’-review& editing. Ruowen Wang: Methodology, Writing’-review& editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Wu, L., Luo, Y. et al. Integrated export instream coefficient model for accurate nonpoint source pollution estimation and management in the Yellow River Basin. Sci Rep 15, 26302 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99552-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99552-1