Abstract

Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy has been successfully used in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, its application to potentially resectable IIIA/IIIB NSCLC remains controversial. This retrospective study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy followed by conversion surgery in patients with potentially resectable stage III NSCLC, focusing on conversion rate and survival benefits. Patients with ‘potentially resectable’ stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC who were deemed unsuitable for complete (R0) resection at initial diagnosis were retrospectively identified. After 2–4 cycles of treatment, all patients were reevaluated for surgical resectability. Data on patient characteristics, radiological and pathological responses, and survival outcomes were collected. In total, 148 patients were included in the final analysis. Upon the completion of neoadjuvant therapy, 105 patients were considered suitable for conversion surgery. Three patients refused surgery, and 102 patients ultimately underwent surgery, yielding a conversion rate of 70.9% and a resection rate of 68.9%. The rate of complete (R0) resection was 100%, with a major pathological response (MPR) of 64.7% and a pathologic complete response (pCR) of 41.2%. Postoperative complications were observed in nine patients (8.8%), and there was no surgery-related mortality within 30 days. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 19.1 months in the non-surgery group, and the overall survival (OS) was not reached. In the 102 patients who underwent conversion surgery, both the median PFS and OS were not reached, accompanied by 2-year OS and PFS rates of 87.3% and 78.4%, respectively. Our findings showed that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy expanded the opportunities for conversion surgery in potentially resectable cases. Subsequent conversion surgery is safe and has the potential for significant survival benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Stage III non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a locally advanced disease that accounts for 30% of NSCLC cases1. Notably, patients with stage III NSCLC exhibit significant heterogeneity and can be classified as resectable, potentially resectable and unresectable2. Approximately 20% of patients with NSCLC are diagnosed with potentially resectable (stage IIIA or IIIB) disease due to direct organ invasion (T4) or mediastinal lymph node spread (N2)3,4. Over the past decades, many treatment strategies such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery, concurrent or sequential chemoradiotherapy (CRT/SRT), and surgery after CRT, have been attempted in patients with potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC5,6,7. Unfortunately, these efforts have yielded minimal advancements with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 41% for stage IIIA and 24% for stage IIIB8, thus warranting the exploration of alternative treatments.

Programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors have shown promising anticancer effects in metastatic NSCLC therapy. Moreover, many studies have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for resectable stage III NSCLC9,10,11,12. Provencio et al.13 reported a 90% downstaging rate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab in resectable stage IIIA NSCLC, and the OS at 36 months was 81.9%. Forde et al.14 reported in a phase III trial that neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy followed by surgical resection significantly prolonged event-free survival (EFS 31.6 vs. 20.8 months) and increased the pathological complete response (pCR, 24.0 vs. 2.2%) compared to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable stage IB-IIIA NSCLC patients. As for potentially resectable stage III NSCLC, it remains an open question whether neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy can be used for potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, leading to downstaging from unresectable to resectable disease and, in turn, improve long-term survival.

Herein, we retrospectively reviewed a case series of potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC patients successfully downstaged by neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy who subsequently underwent conversion surgery, with focus on the surgical outcomes and survival benefit.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient selection

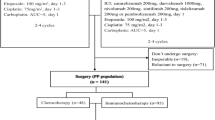

Patients with potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC who received 2–4 cycles of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy between January 2021 and December 2022 at Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute were recruited in the study (Fig. 1). The main inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histologically confirmed NSCLC; (2) stage III tumors according to UICC/AJCC staging standards (8th edition) and deemed potentially resectable by a multidisciplinary team (MDT); (3) completed at least two cycles of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy and subsequently re-evaluated for surgical eligibility; and (4) available tissue specimens for pathological evaluation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) prior antitumor treatments before admission; (2) other significant concurrent malignant tumors, and (3) lack of complete clinical data.

The ‘potentially resectable’ condition was defined as follows: tumor invasion into vital structures (e.g., main vessel roots, trachea or other unresectable organs that affected indispensable physiological functions) or the presence of multiple enlarged ipsilateral mediastinal lymph nodes4. Although R0 resection was unfeasible at the time of initial diagnosis, the possibility of achieving such a resection arose after neoadjuvant treatment. Patient suitability for surgery before and after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy was determined by a MDT including oncologists, radiological specialists, pathologists and thoracic surgeons. Candidates eligible for surgery underwent surgery by a group of experienced thoracic surgeons; otherwise, the patients received radiotherapy-based radical treatment.

For initial evaluation and staging, enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan, brain MRI, bone scanning, and abdominal CT were routinely performed. Positron emission tomography–CT (PET/CT) or endobronchical ultrasound (EBUS) biopsy was performed on patients with mediastinal lymph node metastases. After induction immune-chemotherapy, candidates for subsequent operation should have confirmed lymph node down-staging assessed by enhanced chest CT scan or PET/CT and with (1) no bulky mediastinal mass; (2) no sign of direct tumor invasion to great vessels, diaphragm, heart, trachea, and carina (to ensure complete resection of tumor); and (3) no progression and distant metastasis.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute and in conformity to the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Radiological and pathological response evaluation

Radiology experts evaluated the radiological response according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST v.1.1), including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). The pathological response following neoadjuvant therapy was determined by examining the percentage of residual viable tumor in the resected tumor based on the IASLC Pathology Committee’s recommendations15,16,17. Major pathological response (MPR) was defined as the presence of 10% or less cells, and pCR was defined as the absence of viable tumor cells in both the primary tumor and lymph nodes.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the surgical resection rate of all enrolled patients. The secondary endpoints included MPR, pCR, progression-free survival (PFS, time from the date of pathological diagnosis to disease recurrence or death), and overall survival (OS, time from pathological diagnosis to death). Efficacy-related endpoints, including the overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR), were assessed according to the RECIST v.1.1. Preoperative clinical staging and postoperative pathological downstaging were performed according to the eighth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging System.

Biomarker assessments

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CD4, CD8, and PD-L1 was conducted on 69 paired pretreatment tumor biopsies and post-treatment surgical specimens following protocols from our previous study18. All slides were scanned and recorded with a Pannoramic 250FLASH (3DHISTECH, Hungary) and viewed with a CaseViewer 2.4 (3DHISTECH). T lymphocyte densities in the tissues were quantified using the Qupath software (v. 0.3.2, https://qupath.github.io), and the average density across 10 regions of interest (ROIs) was calculated and expressed as the proportion of positive cells per tissue area (mm2). The immunohistopathology score (H-score) was calculated using the following equation: H-score = (percentage of weak-intensity cells ×1) + (percentage of moderate-intensity cells ×2) + (percentage of strong-intensity cells ×3).

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test or Fisher’s test was used to compare categorical variables between the groups, and the results are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was subsequently performed to determine optimal cutoff values. Survival probabilities were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A P value of less than 0.05 was taken to be significant. Statistical analysis and graphing were performed using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Study population

Between January 2021 and December 2022, a total of 148 patients diagnosed with potentially resectable stage III NSCLC, who received anti-PD-1(L1) antibodies combined with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment were recruited. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, most patients were male (90.5%), had ever smoked (69.6%), and had squamous cell carcinoma (LUSQ, 73.0%). The disease was staged as clinical stage IIIA or IIIB in 104 (70.3%) and 44 (29.7%) patients, respectively. According to whether the patients underwent radical conversion surgery, 102 and 46 patients were assigned to the surgery and non-surgery groups, respectively. Compared with the surgery group, the median age was older (66 vs. 62 years, p = 0.038), and more patients with stage IIIB disease (41.3% vs. 24.5%, p = 0.039) were observed in the non-surgical group. Within the surgery group, the majority of the 87 patients (85.3%) received postoperative adjuvant treatment, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, combined immune-chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. However, 15 patients abstained from adjuvant therapy maybe because of cost or age factors. Among those who did not undergo surgery, 3 patients refused any remaining treatment, and the other 43 (93.4%) patients underwent radiotherapy-based radical treatment.

Surgical outcomes

Upon completion of neoadjuvant treatment, 105 of the 148 (70.9%) patients were considered suitable for surgery. Three patients refused surgery at their own discretion, and 102 ultimately underwent surgery, yielding a resection rate of 68.9%. In the surgery cohort, the median interval from the last dose of neoadjuvant therapy to surgery was 35.5 days, with a range of 21 to 125 days. Fifteen (14.7%) patients had a surgical delay (time from last neoadjuvant dose to surgery > 6 weeks), of which six patients (5.9%) were attributed to treatment-related adverse events. Of the surgical procedures performed, 37 (36.2%) underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), and 59 (57.8%) underwent thoracotomy. In six patients (5.9%), surgeries initially planned for VATS were converted to thoracotomies. 6 patients (5.9%) underwent pneumonectomy, and 96 patients (94.1%) underwent lobectomy combined with routine mediastinal lymphadenectomy. The median surgical time was 120 min (range: 73–270), and the average blood loss was 135 ml (range: 30-1500). The most frequent postoperative complication was anemia, which occurred in 4 of 102 patients. Notably, no surgery-related mortality occurred within 30 days (Table 2).

Radiological and pathological response

The overall response was evaluated after 2–4 cycles of neoadjuvant treatment according to the RECIST 1.1 criteria as depicted in Fig. 2A. No patient achieved CR, 101 (68.2%) achieved PR, 43 (29.1%) had SD, and 4 (2.7%) had PD during neoadjuvant treatment. The ORR post-chemotherapy was 68.2% and the DCR was 97.3%. Among patients who underwent surgery, 85 (83.3%) experienced pathological downstaging of their clinical disease stage. Postoperative pathological assessments revealed that 66 patients (64.7%) achieved MPR, including 42 patients (41.2%) with pCR (Fig. 2B). A significantly greater proportion of patients who achieved an MPR were noted among those who achieved a PR (69.6%) than among those with an SD (43.5%) (p = 0.022, Fig. 2C).

Radiological and pathological responses. (A) Pretreatment and post-treatment CT images of representative radiographic responses with PR, SD and PD. (B) Pathological responses (pCR and MPR rate inthe surgery group) to neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy (C) The association between radiological and pathological responses in surgical patients. PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progression disease, pCR pathologic complete response, MPR major pathological response.

Survival outcomes

At the data cutoff date of August 2024, the median follow-up time was 31.3 months (95% CI: 29.4–33.2) for the 148 patients enrolled. Median PFS and OS were not reached. The PFS and OS rates at 2-year were 68.5% and 82.1%, respectively. Moreover, in the surgery group, the 2-year PFS and OS rates were 78.4% and 87.3%, respectively, which were greater than the 2-year PFS (45.1%) and OS (70.1%) rates in the non-surgery group. Among the 46 patients who did not undergo surgery, 25 (54.7%) experienced relapse and the shortest PFS was only 4.7 months.

Thus, the surgical group exhibited significantly better PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p = 0.0015) than the nonsurgical group, as shown in Fig. 3A-B. Additionally, patients who had a radiological response (CR + PR) tended to have longer PFS (p = 0.46) and OS (p = 0.058) than those in the non-response group (SD + PD), although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3C-D). In the surgery cohort, patients who achieved an MPR also exhibited a more favorable survival trend than those who did not achieve an MPR (Fig. 3E-F). This study also examined the impact of adjuvant maintenance therapy after surgery. The results indicated that patients who received adjuvant therapy had significantly improved PFS (p = 0.03) and OS (p < 0.001) compared with those who did not receive adjuvant therapy (Fig. 3G-H).

Kaplan-Meier of PFS and OS. (A,B) The difference in PFS and OS between the surgery group and the non-surgery group. (C,D) The difference in PFS and OS between the response group and the non-response group. (E,F) The difference in PFS and OS between the MPR group and the non-MPR group. (G,H) The difference in PFS and OS between the patients with and without adjuvant therapy. PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival.

Biomarkers analysis

In our study, IHC was used to examine PD-L1, CD4 and CD8 expression in paired tumor biopsies from 69 patients before and after treatment. Here, we aimed to investigate the relationship between these immune markers and the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

The results revealed no significant differences in the densities of these markers between the MPR and non-MPR groups in either the pre-treatment or post-treatment samples (Fig. 4A-C). However, when assessing the changes in immune profiles during neoadjuvant treatment, a notable trend emerged. As indicated in Fig. 4D, there was a significant increase in CD4 + and CD8 + T lymphocyte densities coupled with a decrease in PD-L1 expression post-treatment in all patients (p < 0.05). In patients without MPR, similar increases in CD4 + and CD8 + T lymphocyte infiltration were observed. However, in MPR patients, no significant changes in immune profiles were detected, potentially due to the small sample size (Fig. 4A-C). These findings suggest that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy notably elevates TIL infiltration and reduces PD-L1 expression in NSCLC patients; however, baseline TILs and PD-L1 levels do not seem to be predictive of pathological response to treatment.

Representative cases of MPR patient and non-MPR patients with the results of IHC staining of TIME immune markers at baseline and after neoadjuvant treatment, respectively. (A) Comparison of infiltrating CD4 + TILs between the MPR group (n = 40) and the non-MPR group (n = 29) before and after treatment. (B) Comparison of infiltrating CD8 + TILs between the MPR group (n = 40) and the non-MPR group (n = 29) before and after treatment. (C) Comparison of the expression of PD-L1 between the MPR group (n = 40) and the non-MPR group (n = 29) before and after treatment. (D) Comparison of infiltrating CD4+, CD8 + TILs and expression of PD-L1 in all patients before and after treatment. TIME tumor immune microenvironment, TILs tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

Discussion

Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy followed by surgery has provided excellent survival benefits for patients with resectable NSCLC. However, in the context of potentially resectable NSCLC, the role of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy and subsequent conversion surgery deserves further analysis. In this study, we confirmed that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy effectively transformed potentially resectable NSCLC into resectable NSCLC with a conversion rate of 70.9% and a resection rate of 68.9%. Moreover, the 2-year PFS and OS rates in the surgery group were higher than those of patients in the non-surgery group.

Recently, many clinical trials on neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy have been conducted for resectable NSCLC. One of the most important focuses is the surgical resection rate. For instance, the Checkmate-816 trial reported a resection rate of 83.2% (149/176)14, the NADIM trial reported 89.1% (41/46)19 following nivolumab with chemotherapy, the NeoTAP01 study reported 90.9% (30/33)20, and a trial involving atezolizumab with chemotherapy reported a 97% (29/30) resection rate21. The main reasons for not proceeding to surgery in these studies were disease progression, adverse events (AEs), and patient refusal. In our study, the surgical resection rate was 68.9%, which is somewhat lower than that reported in previous studies of resectable NSCLC. This could be attributed to our inclusion of initially unresectable patients who generally presented with larger tumors and had poorer prognoses than those deemed resectable. Another retrospective study focusing on potentially resectable NSCLC reported a resection rate of 65.8% following neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy, further supporting our results4. Therefore, the high rate of surgical resection preliminarily supports the feasibility of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for patients with potentially resectable NSCLC; however, this should be verified via therapeutic and survival analyses.

The therapeutic effect of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in patients with resectable NSCLC has been highlighted in numerous studies. For instance, the NADIM trial by Provencio et al.19 revealed that 83% of stage IIIA NSCLC patients reached an MPR and 63% achieved a pCR with an ORR of 76%. Similarly, in a phase 2 study, Shu et al.21 observed that neoadjuvant atezolizumab combined with chemotherapy resulted in MPR and pCR in 57% and 33% of patients, respectively. In comparison, our preliminary findings indicated that in the surgical group, 64.7% of the patients achieved MPR and 41.2% achieved pCR. Among all patients enrolled in our study, 68.2% had an ORR, and both of these results were comparable to those for resectable NSCLC patients.

The clinical value of neoadjuvant therapy lies in its ability to make surgery feasible and to improve survival outcomes. When complete resection is feasible, surgery remains the ultimate form of local disease control. Our study revealed that patients who underwent sequential surgical resection following neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy experienced a more favorable PFS and OS than those who did not undergo surgery. The 2-year PFS and OS rates in the surgical group were 78.4% and 87.3%, respectively, which are in line with the outcomes reported in resectable NSCLC studies14,19,22,23. Notably, the median PFS of 19.1 months in the non-surgery group receiving radiotherapy-based radical therapy after neoadjuvant treatment surpassed the median PFS (16.8 months) observed in the PACIFIC trial but was shorter than the median PFS (30.6 months) observed in the KEYNOTE-799 trail24. These findings suggest that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy could convert some initially unresectable NSCLC into resectable NSCLC, and subsequent surgical intervention could achieve survival benefits comparable to those of resectable NSCLC. For patients with unresectable NSCLC, the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy followed by radiotherapy-based radical therapy is no less than that of standard therapy (PACIFIC). However, the median PFS in our study was shorter than that in the KEYNOTE-799 study, possibly due to the delay in radiotherapy and lack of immune consolidation treatment after radiotherapy. Current guidelines do not specify the contribution of adjuvant maintenance therapy in patients who have undergone surgery. Despite no consensus on postoperative adjuvant treatment, most phase 3 trials—except the CheckMate 816 study—have mandated adjuvant immunotherapy for 1 year in an attempt to eradicate residual disease. However, a another meta-analysis suggests that adding PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors in the adjuvant phase to neoadjuvant treatment with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors and chemotherapy may not improve survival outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC and may be associated with increased adverse events25. In our study, patients who received adjuvant therapy exhibited significantly improvements in both PFS and OS compared to those who did not receive such treatment. But due to the limited population of patients in the non-adjuvant-treated cohort, the results require further validation with a larger sample size.

The safety of sequential surgery after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy is another important factor to be considered. No perioperative mortality was observed in this study. Only nine (8.8%) patients had postoperative complications, including anemia, chylothorax, pneumonia and postoperative arrhythmia, which are comparable to those of previous trials. Of the 43 patients for whom minimally invasive surgery with VATS was planned, 6 (5.9%) underwent elective conversion to thoracotomy. All surgical procedures are rigorously evaluated by surgeons; however, a small subset of patients initially scheduled for thoracoscopy required conversion to thoracotomy due to the identification of intrathoracic adhesions or hilar fibrosis during the operative procedure. To our knowledge, existing literature demonstrates significant heterogeneity in reported conversion rates in potentially resectable NSCLC. In Jiang et al.’s cohort, 4 patients (11.1%) required conversion from thoracoscopy to thoracotomy4. However, another study reported by Ma et al. found there was no instance of conversion to thoracotomy26. In addition, the surgical time and blood loss levels were consistent with those reported in other trials3,27.

Numerous studies have underscored the critical role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME)18,28,29. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy is superior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in terms of mechanisms in which ICIs can reverse T-cell exhaustion and continuously enhance the generation of mature memory T cells, especially tissue-resident CD8 + memory T cells (Trm cells), to provide long-term immune memory protection and good clinical efficacy. However, few studies have reported the changes in and prognostic value of TIME in patients with NSCLC treated with NACT. Our study was designed to analyze CD4 + and CD8 + TIL levels and PD-L1 expression in pre- and post-treatment tumor samples to determine the correlation between these parameters and pathological response. Consistent with the findings of previous research, our study revealed significant changes in immune markers, including increased CD4 + and CD8 + TILs and reduced PD-L1 expression. Priming of CD4 + and CD8 + TILs is involved in the signaling of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and contributes to efficient and durable antitumor immunity30,31. While TIL infiltration is often linked to the tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors32,33, our findings did not reveal a correlation between baseline CD4 + and CD8 + TIL counts and the efficacy of immunotherapy. PD-L1 expression is an FDA-approved biomarker for predicting immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced NSCLC. Several studies have indicated that high PD-L1 expression is associated with improved survival in advanced NSCLC patients34,35. However, the importance of PD-L1 as a predictive factor for response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC has not been fully elucidated. For instance, the NEOSTAR study36 reported a link between higher pretreatment PD-L1 levels and greater pathological response post-treatment, whereas the Checkmate-159 trial37 found no correlation between MPR rate and PD-L1 expression at diagnosis. Similar results were observed by Shu et al.21, where PD-L1 expression was not a reliable predictor of treatment benefits in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy. Our study revealed no direct correlation between baseline PD-L1 expression and MPR, which is consistent with the data shown in Checkmate-159 trials. Therefore, the predictive role of PD-L1 in neoadjuvant immunotherapy remains controversial and requires further investigation.

This study had several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of our study might have led to a large amount of bias in patient selection and statistical analysis. The patients were not randomly assigned to the surgery or non-surgery groups. Patients who responded well to induction immunochemotherapy and were in good physical condition (e.g. good ECOG-PS, less comorbidities and better lung functions) were selected for sequential surgery, possibly affecting survival outcomes. Further prospective randomized trials with larger sample sizes are required to validate our results. Second, the distribution of pathological types was not balanced, as more than 70% of patients had squamous cell carcinoma. Finally, the duration of follow-up was relatively short, and the median PFS in the surgery group and median OS in both groups were not reached. Extended follow-up periods are necessary to fully assess the potential long-term survival benefits of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in these patients.

In summary, our retrospective analysis suggests that the use of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy expanded the opportunities for conversion surgery in potentially resectable cases. Subsequent conversion surgery is safe and has the potential for significant survival benefits.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L. et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72 (1), 7–33 (2022).

Eberhardt, W. E. et al. 2nd ESMO consensus conference in lung cancer: locally advanced stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 26 (8), 1573–1588 (2015).

Deng, H. et al. Radical minimally invasive surgery after Immuno-chemotherapy in Initially-unresectable stage IIIB Non-small cell lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. 275 (3), e600–e602 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Safety and effectiveness of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (toripalimab) plus chemotherapy in stage II-III NSCLC (LungMate 002): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. BMC Med. 20 (1), 493 (2022).

Pless, M. et al. Induction chemoradiation in stage IIIA/N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet 386 (9998), 1049–1056 (2015).

Albain, K. S. et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374 (9687), 379–386 (2009).

Le Pechoux, C. et al. Postoperative radiotherapy versus no postoperative radiotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer and proven mediastinal N2 involvement (Lung ART): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23 (1), 104–114 (2022).

Stefani, D. et al. Lung Cancer surgery after neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Cancers. 13(16). (2021).

Sorin, M. et al. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for NSCLC: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 10 (5), 621–633 (2024).

Spicer, J. D. et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments for early stage resectable NSCLC: consensus recommendations from the international association for the study of lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 19 (10), 1373–1414 (2024).

Presley, C. J. & Owen, D. H. Improved survival for patients with lung cancer treated with perioperative immunotherapy. Lancet 404 (10459), 1176–1178 (2024).

Banna, G. L. et al. Neoadjuvant Chemo-Immunotherapy for Early-Stage Non-Small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (4), e246837 (2024).

Provencio, M. et al. Overall survival and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in operable stage IIIA Non-Small-Cell lung Cancer (NADIM phase II trial). J. Clin. Oncol. 40 (25), 2924–2933 (2022).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386 (21), 1973–1985 (2022).

Travis, W. D. et al. IASLC multidisciplinary recommendations for pathologic assessment of lung Cancer resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15 (5), 709–740 (2020).

Weissferdt, A. et al. Pathologic processing of lung Cancer resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy. Mod. Pathol. 37 (1), 100353 (2024).

Dacic, S. et al. International association for the study of lung Cancer study of reproducibility in assessment of pathologic response in resected lung cancers after neoadjuvant therapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18 (10), 1290–1302 (2023).

Jia, W. et al. High post-chemotherapy TIL and increased CD4 + TIL are independent prognostic factors of surgically resected NSCLC following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. MedComm 2023 (4), pe213 (2020).

Provencio, M. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nivolumab in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NADIM): an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21 (11), 1413–1422 (2020).

Zhao, Z. R. et al. Phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant Toripalimab with chemotherapy for resectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 10 (1), 1996000 (2021).

Shu, C. A. et al. Neoadjuvant Atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21 (6), 786–795 (2020).

Rothschild, S. I. et al. SAKK 16/14: durvalumab in addition to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage IIIA(N2) Non-Small-Cell lung Cancer-A multicenter Single-Arm phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (26), 2872–2880 (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. Neoadjuvant sintilimab and chemotherapy for resectable stage IIIA Non-Small cell lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 114 (3), 949–958 (2022).

Antonia, S. J. et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III Non-Small-Cell lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 (20), 1919–1929 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant vs Neoadjuvant-Only PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors for patients with resectable NSCLC: an indirect Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (3), e241285 (2024).

Sun, C. et al. Efficiency and safety of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (sintilimab) combined with chemotherapy in potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB non-small cell lung cancer: Neo-Pre-IC, a single-arm phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 68, 102422 (2024).

Sepesi, B. et al. Surgical outcomes after neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab with ipilimumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 164 (5), 1327–1337 (2022).

Gaudreau, P. O. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases cytotoxic T cell, tissue resident memory T cell, and B cell infiltration in resectable NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16 (1), 127–139 (2021).

Parra, E. R. et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on the immune microenvironment in non-small cell lung carcinomas as determined by multiplex Immunofluorescence and image analysis approaches. J. Immunother. Cancer. 6 (1), 48 (2018).

Borst, J. et al. CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18 (10), 635–647 (2018).

Freud, A. G. et al. The broad spectrum of human natural killer cell diversity. Immunity 47 (5), 820–833 (2017).

Han, R. et al. Tumor immune microenvironment predicts the pathologic response of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 114 (6), 2569–2583 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Response to neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors and chemotherapy in Chinese patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the role of tumor immune microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 72 (6), 1619–1631 (2022).

Gadgeel, S. et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (14), 1505–1517 (2020).

Akinboro, O. et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab, Atezolizumab, and Cemiplimab-rwlc as single agents for First-Line treatment of advanced/metastatic PD-L1-High NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res. 28 (11), 2221–2228 (2022).

Cascone, T. et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 randomized NEOSTAR trial. Nat. Med. 27 (3), 504–514 (2021).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in resectable lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (21), 1976–1986 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province [grant number: ZR2022MH049 and ZR2023QH388] and Shandong Province Medical and Health Technology Project [grant number:202304021418].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yana Qi: Conceptualization, data curation and writing-original draft. Yulan Sun: Conceptualization and writing-original draft. Yanran Hu: Data curation. Hui Zhu: Resources and supervision. Hongbo Guo: Writing-review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute and in conformity to the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, Y., Sun, Y., Hu, Y. et al. Clinical outcomes of conversion surgery following neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB non-small cell lung. Sci Rep 15, 18422 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99571-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99571-y