Abstract

Understanding landscape multifunction trade-offs and synergies is fundamental to achieve the regional sustainable management and improving human well-being. Taking the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area as an example, this paper quantitatively evaluates residents’ carrying function (RC), food production function (FP), habitat maintenance function (HM), water conservation function (WC) and landscape aesthetic function (LA) in 2022. On the basis of constructing the multifunctional landscape model of the Bayesian belief networks, the key nodes that affect the landscape function are identified by analyzing the importance of nodes. Joint probability distribution, probabilistic reasoning and scenario simulation were used to explore the synergistic and trade-off relationship of landscape multifunction and its driving factors. The results show that: (1) The spatial heterogeneity of RC, FP, HM, WC and LA in the Greater Bay Area is significant. The distribution of RC and FP is relatively consistent, with high values concentrated in the northeastern plain and coastal areas, and low values distributed in the mountainous and hilly areas of the northwest and southwest. The distribution of HM, WC and LA is relatively consistent, showing a spatial pattern of high hills in the northwest and southwest mountains and low in the northeast plain and coastal areas. (2) There is a synergistic relationship between HM, WC and LA. There is a trade-off relationship between RC-WC, FP-HM and FP-LA. (3) Land use type and NDVI are the main factors affecting the synergistic relationship of landscape multifunctional. Population density and altitude are the main factors affecting the trade-off relationship. It is found that different drivers generate the same synergy (or trade-off) in different states, while the same drivers generate different synergy (or trade-off) in different states. This study has important theoretical and practical value for understanding the complex relationship between landscape multifunctionality and the differences in driving factors, and for proposing countermeasures and measures to improve landscape ecosystem management and human well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the symposium “Multifunctional landscape: an interdisciplinary approach to landscape research and management” held in Denmark in 2000, the concepts of multifunctional landscape and landscape multifunctionality began to enter the academic field, and the research on landscape multifunctional has gradually attracted the attention of the academic community1,2,3,4. Landscape multifunctionality refers to the feature that landscape provides multifunctional at the same time and different functions interact with each other5,6. Exploring and analyzing the trade-off and synergy between different landscape functions has become one of the important directions7,8,9,10,11. The study on how to identify the nonlinear relationships among landscape multifunction and their influencing factors has become one of the hot topics in this direction, which has important theoretical and practical significance for realizing the sustainable development of landscape ecosystem management and improving human well-being12,13.

Current research methods for studying landscape multifunction relationships include functional mapping, scenario analysis and statistical methods14,15. The landscape functional mapping reflects spatial heterogeneity but requires in-depth analysis16,17. The correlation analysis through statistical methods is effective, but may ignore spatial heterogeneity and fail to explore the driving mechanism comprehensively18,19. The scenario analysis primarily focuses on land use change and optimization, but landscape multifunction is the result of multiple driving factors20. Few studies have discussed the driving factors and mechanisms of landscape multifunction relationships. The geographic detector model, ordinary least squares model and geographically weighted regression is commonly used, but they have limitations in capturing driving mechanisms and non-linear interactions between functions14. There is still a great potential for improvement in accurately expressing the internal mechanism and driving factors of the trade-off and synergy relationship among landscape multifunction.

With the deepening of landscape ecosystem research, the demand for landscape ecosystem modeling is increasing21. However, due to the complexity of the landscape multifunction supply process and the difficulty of accurate measurement, landscape functional modeling fails to adopt complex quantitative models22. The subjective factors of the qualitative model are difficult to control, resulting in inaccurate models. As a semi-quantitative model, the BBNs has the advantages of intuitive graphical representation and quantitative simulation, and can be used for landscape function modeling23. For example, Zeng et al. (2019) and Dang et al. (2019) used Bayesian network to simulate the process of water conservation function, predicted the probability of water conservation service state in 2050 according to different land use scenarios, and optimized the spatial pattern of water conservation service in Guan-tian Economic Zone24. The latter is based on Bayesian network model to explore the impact of environmental and human factors on rice supply services, optimize rice supply capacity and provide decision support for sustainable agricultural development25. The current studies integrating the BBNs and the landscape function have simulated the effects of a single landscape function supply or various factors on a certain landscape function, but there are few applied studies on landscape functional trade-offs and synergies. In addition, the predictive analysis of the BBNs has been fully utilized in existing research, while the application of diagnostic analysis needs to be further explored. The BBNs can link multiple factors to landscape functions, intuitively simulate landscape ecological processes and make inferences based on assumptions for research purposes. Therefore, the changes in network nodes can be easily observed through BBNs, thus revealing the interrelations of landscape functions and their driving mechanisms26. That is, within a certain regional scope, how to construct a Bayesian network model based on multiple landscape functions and identify multiple nonlinear relationships among multifunctional and their driving factors are the research focus and key problem to be solved in this paper.

The Zhejiang Greater Bay Area, experiencing rapid urbanization in China, faces environmental challenges such as farmland loss, wetland reduction and habitat fragmentation due to population growth and economic development27. Based on this, this paper takes the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area as the research object to quantitatively evaluate 5 landscape functions of RC, FP, HM, WC and LA in 2022. Then, this paper constructs a landscape multifunctional model based on Bayesian belief network, analyzes the trade-offs and synergies of 5 landscape functions by using joint probability distribution, and finally discusses the driving factors affecting the trade-offs and synergies of landscape functions. This study is important for improving the understanding of the complex relationship between landscape multifunction and improving the overall benefits of the landscape ecosystem in the study area.

Study area and data sources

Overview of the study area

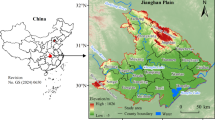

The Zhejiang Greater Bay Area is located on the southern wing of the Yangtze River Delta, connecting with Xiangshan Bay, Sanmen Bay, Taizhou Bay, Wenzhou Bay, and Yueqing Bay, among others. It includes 8 cities such as Hangzhou, Ningbo, and Shaoxing (Fig. 1). Thanks to its advantageous location by the sea and dynamic market economy, the Bay Area has been one of China’s fastest-growing economic and urbanization regions in the past 40 years. From 2005 to 2022, the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area experienced rapid development, with accelerated urbanization attracting a large influx of population. The permanent resident population increased from 36.26 million to 39.86 million. The region has diverse terrain, with the north mainly consisting of plains, the east characterized by hills and coastal plains, and the central area predominantly hilly. The climate here is typical subtropical monsoon humid, with an average annual precipitation of about 1600 mm and an average annual temperature ranging from 15 °C to 18 °C. The vegetation coverage rate is 60.21%. The Pearl River Delta’s construction land is concentrated in the Hangzhou-Jiaxing-Huzhou Plain and Ningbo-Shaoxing Plain, with 70% of the construction land coverage along the core development axis between Hangzhou city and Ningbo city. Other areas along this line are nearing saturation in terms of urban and rural land boundaries. It is evident that urbanization, high-density land use, and population growth are increasingly exerting pressure on the regional ecological environment. Therefore, strengthening ecological protection and achieving coordinated development between the economy and the environment in the Greater Bay Area is crucial28.

Overview of the study area. This map was created using ArcGIS Pro software (esri.com) based on the standard map No. GS(2019)1822 from the Standard Map Service of the Ministry of Natural Resources (http://211.159.153.75/).

Data sources and processing

In this study, we have collected a multi-source dataset for landscape multifunction assessment and driver analysis. (1) Land use data in 2022: sourced from the National Earth System Science Data Sharing Service Platform (http://www.geodata.cn). According to the Chinese national standard “Classification of Land Use Status” (GB/T21010-2007), it is classified into 6 categories: farmland, forest, grassland, water, construction land and unused land, with a spatial resolution of 30 m. (2) DEM: derived from DEM raster of ASTER GDEMS dataset of geospatial Data Cloud platform (http://www.resdc.cn), with a resolution of 30 m. (3) NDVI: sourced from the Geographic Spatial Data Cloud Platform (http://www.resdc.cn), derived from OLI and ETM imagery data. The NDVI data was obtained after processing remote sensing images with ENVI software, with a resolution of 1 km. (4) Meteorological data: spatial interpolation data of temperature, precipitation and latent evapotranche, with a resolution of 1 km, are from the National Earth System Science Data Center (http://www.geodata.cn). (5) Grain production data: from the statistical yearbooks of cities and counties in Zhejiang Province. (6) Population density data: sourced from the Resources and Environmental Data Cloud Platform (http://www.resdc.cn), with a resolution of 1 km. (7) DMSP-OLS nighttime light data: sourced from the National Geophysical Data Center (http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov), with a resolution of 1 km. (8) River data: sourced from the Geographic Space Data Cloud Platform (http://www.resdc.cn), with a resolution of 1 km. All data were preprocessed on the ArcGIS 10.7 platform, with all raster data resampled to a spatial resolution of 1 km. Additionally, the data were projected using the Albers projection.

Methods

Landscape multifunction quantification

A landscape function classification framework that prioritizes carrying functions, production functions, habitat functions, regulatory functions, and information functions is considered a viable approach for addressing land use conflicts in landscape planning29,30. The Greater Bay Area, characterized by diverse landscape types and functions, faces various land use problems27, including biodiversity reduction and greenhouse effects, which have implications for the well-being of its residents (such as housing, food, and water). Referring to the relevant studies of Li et al. (2016) and Liang et al. (2021), we selected the residential carrying function (RC), food production function (FP), habitat maintenance function (HM), water conservation function (WC) and landscape aesthetic function (LA), for comprehensive evaluation in the Greater Bay Area4,31.

Specifically, Residential carrying function is mainly based on the secondary land classes of construction land and can be combined with the regional population for multiple linear regression analysis to determine the population distribution coefficient of each secondary land class and subsequently obtain the residential carrying index at the grid scale32. In regard to Food production function, human food sources include not only grain crops but also other crops to ensure human survival. When calculating the value of the food supply, the total output value of different land use types was adopted as the research object, and the value of food production in each grid was obtained. Habitat maintenance function and water conservation function were estimated using the habitat quality and water yield modules of the InVEST model, respectively27,33. According to general aesthetic standards, uniqueness of the research area and existing studies, an index system for landscape aesthetic function evaluation was constructed considering the variations in terrain and landscape diversity34. The evaluation results were normalized, and dimensionality was eliminated. The evaluation results were normalized using the Min–Max method to eliminate dimensionality, with all functional calculations based on land use type data. Therefore, all other process data involved in the calculation were converted to a 30-m pixel level.

(1) Residential carrying function It is the ability to provide residential space for human needs4. The spatial distribution regression model of population based on land use data was used for analysis29,30. The calculation process is as follows:

C is the residential capacity of a simulation unit, n is the number of land use types, ki is the coefficient of land use type i of a simulation unit, si is the area of land use type i of a simulation unit, and b is a constant term.

(2) Food production function It refers to the ability to provide food for human survival needs. The spatial distribution model of grain yield based on land use type and food yield was calculated4,19. The calculation process is as follows:

Pi provides value (yuan) for food i in each grid; Ai is the area occupied by food i in each grid (km2); Ni is the output value per unit area of corresponding food i (yuan/km2). Gi is the total output value of food in the study area (yuan); Si is the total area of food i in the study area (km2). The total output value of different types of food corresponds to different types of land use. The total output value of agriculture corresponds to the area of cultivated land, the total output value of forestry corresponds to the area of forest land, the total output value of animal husbandry corresponds to the area of grassland, and the total output value of fishery corresponds to the area of water.

(3) Water conservation function It refers to the water production capacity of plots that regulate runoff and river discharge. In this paper, the Water Yield module of the InVEST model is used to calculate the water yield of water source conservation services, and the specific calculation process is detailed in the reference4,35. The formula is as follows:

Yieldjx represents water yield. j represents a certain land use type. x represents a certain grid cell. ETmean,jx represents average actual evapotranspiration. Rainx represents annual rainfall.

(4) Habitat maintenance function It reflects the ability to provide conditions suitable for the survival of individuals and population conditions. The InVEST is used for the calculation4,35. The formula is as follows:

Qxj is the habitat quality of patch group x in land use type j. Hj is the habitat suitability of land use type j. Dxj is the total threat level of grid x in land use type j. K is the half-satiety constant, usually 0.5. z is a normalized constant, typically 2.5.

Then, farmland land and construction land (rural settlements, urban) are set as the threat factors, and the sensitivity degree of different land classes to the threat factors is set, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

(5) Landscape aesthetics function It is an important part of cultural function, which is closely related to the needs of human spirit and culture and the realization of human welfare. It was characterized by landscape heterogeneity and topographic variation.

The landscape heterogeneity is an important factor affecting landscape aesthetics. The landscape diversity is a common index to characterize landscape heterogeneity, which can reflect the complexity of landscape30. The Shannon Landscape Diversity Index (SHDI), which is widely used to describe landscape heterogeneity, was adopted36. The formula of SHDI is as follows:

Pi is the proportion of the m patch type in the total area; n indicates the number of patch types.

The change of topography and the diversity of landforms are important factors affecting landscape beauty. Compared with plain landscape, the complex and changeable terrain of mountainous and hilly landscape is more attractive. Topographic relief (RDLS) was used to measure the topographic change of landscape. The formula is as follows:

Max(H) and Min(H) are the highest and lowest elevations (m) in the region respectively.

Identification of landscape multifunction

Landscape functions can be recognized via landscape function spatial superposition. This process can be understood by considering that a single pixel in space can explain various landscape functions. Areas can be defined as the supply areas of multiple landscape functions. The supply area of a given landscape function can be determined by the spatial superposition method. The average value of each landscape function was employed as the dividing standard. If the value is greater than the average, the region is defined as 1. This indicates that this area provides strong landscape functions. If the value of the area is below the average, the area is then defined as 0, which indicates that the area does not provide strong landscape functions. According to the classification criteria, an area with a coverage value of 0 is defined as a nonfunctional landscape. If the superposition value is 1, this indicates a single-function landscape. If the superposition value is greater than 1, this indicates a multifunctional landscape.

Landscape multifunctional model based on Bayesian networks

(1) Model construction

The Bayesian networks (BBNs), proposed by Pearl in 1988, is a graphical model based on probabilistic reasoning37. The BBNs consist of two parts: (1) Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) and Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs). The DAG represents the variables as nodes and the arrows connecting them indicate the dependence or independence of nodes, as well as the direction of causality; (2) The CPTs express the relationship between a node and its parent node(s) along with their respective strengths. Each node in the network is classified as either discrete or continuous. The two key steps in creating a BBNs are building the network structure and CPTs. These two steps correspond to the qualitative description and quantitative expression of the problem, respectively. Then, probabilistic reasoning and sensitivity analysis are carried out.

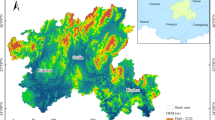

In this paper, the Netica software was used to construct a landscape multifunction model based on the BBNs. According to the process mechanism of multifunction, the relevant variables in the process of landscape function are selected as nodes to conduct structure learning of the BBNs. The network structure contains 7 discrete nodes, 5 continuous nodes and 13 arrows. Among them, 5 functions are the target nodes. The 7 influencing driving variables are the influencing factor nodes. Then, the data layers were discretized using ArcGIS (Table 3). The nodes of LU are discrete variables. The other nodes are continuous variables defined using 4 states. In the range of 0 to 1, the status of each node is classified at equal intervals with 0.25 intervals. The classification of nodes not only considers the equal interval of variable value range, but also considers the distribution law of variable value. After the network structure is completed, the data of 6.76 × 104 sample points obtained by 1 km grid sampling in the study area is taken as the actual case. Furthermore, the CPTs of all nodes in the BBNs are learned. When compiling BBNs, the prior probability distribution of each node state is shown in Fig. 2.

The farmland area in the whole region accounts for 29.21%, and the construction land area accounts for 5.57% of the total area. Moreover, 49.02% of the regional slope values ranges from 0° to 5°. A total of 35.06% of the area provides a good supply of HM, and 34.69% of the area provides the best supply of HM. A total of 47.06% of LA in this area belongs to the good level, and 24.69% of the landscape aesthetic functions belong to the best level, indicating that the evaluated LA supply in this area is high. WC in 77.88% of the study area occurs at a moderate level or above, but the overall water production is good. More than half (51.34%) of the regional RC values is low, indicating that the regional RC value is average. Nearly 80% of the FP values in the region occur above the medium level. Therefore, the overall food production capacity in the region is high.

(2) Model verification

In this paper, the error matrix is used to evaluate the accuracy of the model. Each column of the error matrix represents the forecast category, and the column sum represents the number of forecast categories. Each row represents the actual category. The row sum represents the actual number of categories. A total of 7511 sampling points were generated by creating 3 km × 3 km fishing nets in the study area as validation data. The Netica software was used to test the accuracy of five target nodes, and the error matrix was calculated to evaluate the accuracy of the model. Five nodes, i.e., RC, FP, HM, WC and LA, were adopted as the nodes to be tested, and these variables were regarded as unobserved nodes. The generated predicted values were compared to the true values in case documents (Table 4).

These values can reflect the error between the predicted value and the true value of the target node. The value of the error rate ranges from 0 to 1. An error rate close to 0 indicates that the network accuracy is high. The logarithmic loss ranges from 0 to + ∞. The closer the logarithmic loss is to 0, the higher the accuracy of the network. The secondary loss varies between 0–2, and a value close to 0 indicates the accuracy of the network. Spherical returns range from 0 to 1, with values close to 1 indicating high precision of the network. The overall accuracy of the BBNs constructed in this paper is relatively high, indicating that the BBNs has high accuracy in the process of simulating landscape multifunction supply, and has strong reliability in probability inference.

(3) Analysis of the importance of impact factors to landscape functions

Based on the sensitivity analysis of Netica software, the relative importance of the influencing factor nodes to the landscape function nodes in the model is discussed by calculating the variance reduction.

In the formula, VR is the variance reduction and represents the relative importance; V(Q) and E(Q) are the variance and expectation of landscape function Q. V(Q|F) and E (Q|F) are the variance and expectation of landscape function Q under the condition of variable F; Xq is the true value corresponding to state q. The larger the VR value is, the greater the relative importance of the node to the target node is, that is, the greater its influence on the landscape function node is. Vice versa indicates a smaller impact on landscape function nodes.

Result

Landscape multifunction spatial pattern

Residential carrying function: Through the multifunctional quantitative analysis method, the spatial diagram of the RC (Fig. 3-1) is drawn, and the validity of the spatialization results is verified at the county or district scale. The simulation and actual population at the county scale are shown in the scatter plot (Fig. 4), and the fitting coefficient R2 = 0.876. The areas with high value of RC are mainly located in Hang-Jia-Hu Plain and Yong-shao-Tai Plain. The reason for this distribution pattern lies in the low and flat terrain, which can provide perfect living space, and is conducive to the concentration of all kinds of production and living service facilities, and the boundary of traffic conditions. Under the superior natural and man-made factors, it has become a concentrated area of residents.

The landscape multifunctional spatial pattern of Hangzhou Greater Bay Area in 2022. The base figure is from the same source as Fig. 1.

Food production function: Mainly concentrated in Hangzhou-Jia-Hu plain and coastal zone (Fig. 3-2), the township of fish and rice and coastal aquatic products have obvious advantages. The reason for this pattern is that the plain area is rich in cultivated land resources, and the coastal area is rich in Marine resources, while the other areas are low mountains and hills, and the food production is relatively small.

Water conservation function: High-value areas are mainly concentrated in areas with dense river network and hills and mountains in Zhejiang province, while low-value areas are distributed in urban agglomerations and coastal areas in northeast China (Fig. 3-3). More abundant river network density and vegetation cover help to present different degrees of aggregation of freshwater production. However, urban construction land is not conducive to water conservation.

Habitat maintenance function: The high-value areas are mainly concentrated in the northwest and southwest of the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area (Fig. 3-4). This area is dominated by low mountains and hills, with extensive forest area, and maintains a high level of habitat. The reason for this pattern is that the northwest region is dominated by residential and construction land, with good traffic conditions in the road network and great interference from human activities, so the habitat quality is low Far away, limited human interference.

Landscape aesthetic function: High-value areas are mainly close to coastal zones and areas rich in forest or water (Fig. 3-5). The low-value area is distributed in the urban core area. The high-value areas of landscape aesthetics are mostly composed of water landscape and forest and grassland with high vegetation coverage, and have good transportation conditions.

Distribution characteristics of multifunctional landscapes

According to multifunctional landscape mapping (Fig. 5), 91.26% of the research area provides 2 or more functions. Among them, 35.98% of the area provides 2 kinds functions, mainly in the Hang-Jia-Hu plain. 33.27% of the regions provided 3 types functions, 19.85% provided four types functions, and 2.16% provided five types of landscape functions. Three or more kinds of landscape functions are distributed in the mountainous areas in the southwest and southeast of the region, and the vegetation is rich. In the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area 7.72% of the area is single-function landscape, and 1.02% of the area cannot provide any strong landscape function.

(1) Landscape multifunctionality in Zhejiang Greater Bay Area shows the spatial distribution of landscape multifunction. The base figure is from the same source as Fig. 1; (2) Pie chart shows the area proportion of multifunction; (3) The histogram shows the area proportion of multifunctional landscape in different land use types.

In addition, the diversity of landscape multifunctionality showed obvious heterogeneity in different dimensions of land use/cover types. In general, farmland and forest land were the main land cover types of non-functional landscapes, accounting for 89.71%. The main reason should be that some farmland and forest land are abandoned in the region. The single function landscape is mainly farmland, construction land and unused land, accounting for 96.03%. 75.94% of forest land can provide three or more kinds of landscape functions, and the areas providing five types of landscape functions are mainly forest land, accounting for 98.23%.

Trade-off and synergy relationship of landscape multifunction

Based on Bayes’ theory, BBNs can be employed to infer the posterior probability of an unobserved node from CPTs. By inputting the result of one node and recording the updated posterior probability of other nodes, the trade-offs and synergies among the landscape multifunction in the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area can be determined. Then, the driving mechanism of the relationship between these landscape functions is analyzed.

(1) Entering the findings for the RC node

Four results can be entered (poor = 100%, medium = 100%, good = 100%, best = 100%), and the BBNs provides the posterior probability of updates for the other nodes. The probability inference results of the other functional nodes are shown in Table 6. A line chart is generated according to Table 5, as shown in Fig. 6. With the gradual improvement in the RC node status (from poor to good), the change in the posterior probability distribution corresponding to the FP, HM and LA nodes are irregular and insignificant, resulting in difficulty in identifying the relationship between RC and these three landscape functions. Regarding the FP nodes, the probability of the poor state decreases, the probability of the best state increases, and the mean of SR gradually increases. RC and FP exhibit trade-offs. As the status of the RC node gradually increases from poor to best, the probability of the poor state of the WC node increases, while both the probability and average value of the best state decrease. Notably, the RC and WC nodes indicate trade-offs.

(2) Entering the findings for the FP node

Four results can be entered, and the BBNs display the posterior probability of updates for the other nodes. The probability inference results for the other functional nodes are provided in Table 6. Figure 7 shows a line chart, which is generated according to Table 6. With the gradual improvement in the FP node state from the poor to best states, the posterior probability distribution corresponding to the RC and WC nodes fluctuates and does not show significant results, which makes it difficult to distinguish the relationship between the FP and RC and WC landscape functions. As the state of the FP node gradually increases from poor to best, the probability of the poor state of the HM node shows an increasing trend, while the probability and average value of the best state show decreasing trends. The change in the LA node is similar to that in the HM node. The FP node exhibits a trade-off relationship with the HM and LA nodes.

(3) Entering the findings for the HM node

Four results can be entered, and the BBNs show the posterior probability of updates for the other nodes. The probability inference results for the other functional nodes are provided in Table 7. As the status of the HM node gradually increases from poor to best, the probability of the poor and best states of the LA node decreases and increases, respectively. In addition, the average value of the LA node shows a gradual increasing trend. The above analysis indicates that there is a synergistic relationship between the HM and WC nodes. The WC node value changes similarly to carbon storage. HM exhibits a synergistic effect with WC and LA. As the state of the HM node gradually increases from poor to best, the posterior probability distribution corresponding to the RC node varies and does not show a significant difference, which makes it difficult to distinguish the relationship between the HM and RC nodes. As the state of the HM node gradually increases from poor to best, the probability of the poor state of FP node increases, while both the probability and average value of the best state decrease. Therefore, the HM and FP nodes exhibits trade-offs (Fig. 8).

(4) Entering the findings for the WC node

Four results can be entered, and the BBNs show the posterior probability of updates for the other nodes. The probability inference results for the other functional nodes are shown in Table 8. As the state of the WC node increases from poor to best, the probability of poor state of the RC node increases, while the probability and average of best state of RC node decrease (Fig. 9). The WC and RC are trade-offs. As the state of the WC node gradually increases from “poor” to “best”, the posterior probability distribution corresponding to the FP node changes irregularly and does not show a significant difference. The relationship between the two is difficult to distinguish. As the state of the WC node gradually increases from “poor” to “best” state, the probability of “poor” and “best” state of the HM node decreases and increases, respectively. The average value of the HM shows a gradual increasing trend. The changes of LA were similar to those of the HM. So, the WC has a synergistic relationship with the HM and LA.

(5) Entering the findings for the LA node

Four results can be entered, and the BBNs shows the posterior probability of updates for the other nodes. The probability inference results for the other functional nodes are listed in Table 9. A line plot based on Table 10 is shown in Fig. 10. As the state of the LA node gradually increases from poor to best, the posterior probability distribution corresponding to the RC node varies and does not show a significant difference, and the relationship between these two nodes is difficult to distinguish. As the state of the LA node gradually improves from the poor to best states, the probability of the poor state of the FP node shows an increasing trend, while the probability and average value of the best state show decreasing trends. Therefore, the LA and FP nodes exhibit trade-offs.

As the state of the LA node gradually increases from the poor to best states, the probability of the poor and best states of the HM node decreases and increases, respectively. In addition, the average value of the HM node shows a gradual increasing trend. The changes in the LA node are similar to those in the HM node. The above analysis shows that LA exhibits a synergistic relationship with HM and WC.

Driving mechanism of landscape multifunction trade-offs and synergy

(1) Analysis of the importance of impact factors

In Netica, by targeting nodes such as RC, FP, HM, WC, and LA, sensitivity analysis of the network can reveal the extent to which other nodes influence these target nodes through various sensitivity metrics, thereby identifying key variables affecting the landscape functions of the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area. The variance reduction provided by the Netica software reflects the degree of influence each node has on the target node (Table 10). The key variables affecting the RC include PD, SL and NRD. While the FP is affected by EL and TEM. Key variables affecting HM include PD, SL, VDVI and LU. The Key variables affecting the WC include LU and NDVI. NDVI, LU and SL are the key variables that have great influence on the LA. In addition, the variance reduction values of the RC, FP, HM, WC and LA were all greater than 0, indicating that the five functions were correlated due to the same influencing factors.

The results of probabilistic inference show that the HM, WC and LA are mutually synergistic. There is a trade-off relationship between the RC and WC, and a trade-off relationship between the FP, HM and LA. In the process of probabilistic reasoning, by observing the posterior probabilities of all nodes of the key variables identified by the sensitivity analysis mentioned above, the driving mechanism of the relationship between landscape multifunction can be summarized.

In probabilistic reasoning, it is found that the synergistic effect of landscape multifunction is mainly affected by LU, NDVI, SL and PD. For example, well-vegetated areas are typically located on slopes, with fewer people and minimal human interference in the habitat. Therefore, have better the HM, WC and LA than other areas. In addition, the multifunctional trade-offs are mainly affected by PD, SL, NRD and TEM. The habitat is well maintained, the LA is high, and the water conservation is sufficient, the areas are mainly forest and grassland, but these areas are not convenient transportation, which is not conducive to living.

(2) Driving mechanism of trade-offs and synergies

Identifying the main factors that form trade-offs and synergies and taking targeted measures are the necessary conditions for optimizing landscape multifunctional benefits. According to the results of sensitivity analysis, the nodes of LU, NDVI, SL and PD were taken as the driving factors. Their effects on landscape multifunctional trade-offs collaborative formation can be estimated by Bayesian probabilistic reasoning. The HM, LA and WC are synergistic relationships. In the two scenarios set, the three are regarded as a whole and the reverse reasoning is carried out. For 3 nodes of the created BBNs, the result of “best = 100%” was entered in the Netica to simulate scenario 1. In the scenario 2, all functions are maximized. Accordingly, the result of “best = 100%” is entered to simulate scenario 2 for nodes.

Different from the prior probability that reflects the real situation shown in Fig. 2, the posterior probability shown in Figs. 11 and 12 respectively reflects the final node situation in the two cases. Although the node states of the two scenarios are different, there is no significant difference in the direction and magnitude of the nodes of NDVI, SL and PD. However, the status of LU nodes varies greatly, especially farmland, forest and grassland. That is, the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area optimized the HM, WC and LA, the farmland area decreased by 11.77%, the forest area increased by 10.84%, and the grassland area increased by 1.22%. If the LA and FP are taken into account, the farmland area should be reduced by 2.65%, the forest area should be increased by 4.59%, and the grassland area should be increased by 1.48%. Thus, LU is the most important driving force for the trade-offs between LA and FP (HM and FP). We must give attention to the structure and pattern of land use, especially the spatial distribution of farmland, forestland and grassland.

Discussion

Comparison of the results

The RC, FP, HM, WC, and LA of the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area all show spatial heterogeneity. In terms of the spatial distribution characteristics, the RC shows a spatial pattern of high in the northeastern plain and coastal areas, and low in the mountainous and hilly areas of the northwest and southwest. The main reasons may be as follows: the plain and coastal areas are low and flat, which is conducive to population agglomeration, transportation network layout, and infrastructure construction and development. In addition, the development and use of foreign trade and Marine resource space in the region contribute to human agglomeration. With the addition of innate natural and humanistic conditions, it has become a better living area for human beings in history4. The FP shows a spatial pattern of high in the northeastern plain and coastal areas and low in the western mountainous and hilly areas. The possible reasons are: the plains have a dense water network, fertile arable land, and the coastal waters, which contribute to the abundance of food production. In contrast, the northwest and southwest of Zhejiang are dominated by mountainous and hilly landforms, with scarce cultivated land resources and fewer products38. The WC, HM, and LA show a spatial pattern of high values in the mountainous and hilly areas of the west, and low values in the plain and coastal areas. There is consistency in the spatial layout of these three functions, mainly due to the high vegetation coverage in the mountainous and hilly areas of the west, which contributes to water conservation. This also contributes to habitat maintenance to a certain extent. The northeast is affected by urbanization and cultivated land, and habitat degradation is relatively significant. The LA is more prominent in the southwestern region and coastal zone landscape areas where forests are widely distributed.

The relationship of the landscape multifunctional identified in this paper aligns with the findings of previous studies. Liang et al. (2021) examined landscape functions in Suzhou from and found a synergistic relationship between HM and WC, as well as a trade-off between FP and HM4. Peng et al. (2016) analyzed the trade-offs and synergies among landscape functions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and observed a synergistic relationship between WC and HM, as well as a trade-off between the RC and WC19. Wang et al. (2022) explored the interaction between landscape multifunction in the Sutlej-Beas River basin, indicating a trade-off between the LA and HM and a synergy between the LA and WC39. The future research should employ more comprehensive models to monitor the trade-offs and synergies of landscape multifunctionality in long-term time series.

Impact of land use on landscape functions

Numerous studies have highlighted how land use patterns can affect landscape functions by altering ecological processes15. Unreasonable land use changes can negatively impact landscape functions32. Bayesian probabilistic inference in this study demonstrated that land use changes significantly impact the multifunctional landscape supply and relationships. These changes affect the vegetation fraction, surface runoff, habitat, human activity intensity, and other attributes, ultimately influencing biodiversity conservation, human activity patterns, water cycle processes, and perception of landscape aesthetics. To better understand and manage the impact of land use on human activities and ecological processes, it is crucial to develop policies, improve research techniques, and collect detailed land use data.

The diversification of land use mapped by landscape versatility is bound to lead to more land use conflicts. As managers of cities or regions, they can consider breaking the boundaries of administrative regions, take the multi-functional collaborative and balanced development of landscape in the Greater Bay Area as a powerful starting point for realizing the harmonious coexistence of man and nature in modern development, and support and guarantee the collaborative and sustainable development of regions such as mountain and sea collaboration.

Conclusion

Policy recommendations

The Bay area is a high-level form of urban economic development and a land-sea integration form of urban development, and the trade-off and collaborative development of landscape multifunctional is the basic guarantee for the sustainable development of the Bay Area. For the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area region, the landscape ecosystem can be greatly improved through the intervention and promotion of the core driving factors of the trade-off and synergy relationship of landscape multifunctional.

-

(1)

The ecological conditions of Hang-Jia-Hu Plain urban agglomeration, Yong-shao-Tai Plain urban agglomeration and coastal urban built-up areas continue to improve. Balancing the relationship between urban ecological land protection and construction land development will help to limit the new impervious surface and optimize the layout of green space. In addition, these measures improve the ecological carrying capacity by regulating the water cycle and providing habitats for certain organisms.

-

(2)

In the northwest and southwest low mountain hilly regions, landscapes dominated by forests and grasslands provide strong ecosystem services such as water retention and habitat maintenance, which help maintain and construct regional ecological barriers. Additionally, there is potential for further development of cash crops in mountainous areas, enhancing and stabilizing food production functions. Moreover, these landscapes have various other potential functions, such as serving as carriers for rural tourism and having certain carbon sink capabilities, thereby improving habitat maintenance capacity.

-

(3)

For coastal areas, it is necessary to further promote the sustainable use of marine resources. Based on the types of coastlines and environmental characteristics, we must comprehensively consider factors such as disasters, nature reserves, coastal protective forests, and seaside roads, strictly limit the intensity of land development along the coast, and delineate control lines.

Therefore, to optimize the overall benefits of the ecosystem in the study area, it is essential to enhance synergies between ecosystem services and reduce trade-offs. When making relevant decisions, government departments should focus on key drivers such as land use, vegetation cover, slope, and population density, particularly the structure and pattern of land use, such as the spatial distribution of cropland, forests, and grasslands.

Advantages and disadvantages

(1) Advantages of BBNs

Comparatively, the BBNs provide unique advantages in analyzing multifunctional relationships and their driving mechanisms. Traditional methods often measure the complex interactions between landscape functions with linear models, only considering the values and symbols of phase relationships and employing hypotheses to explain the driving mechanism. However, since landscape function provision is influenced by various interdependent factors, a social-ecosystem perspective is essential. The BBNs constructed in this paper successfully link potential drivers to the supply of multiple landscape functions using DAGs and learn the interaction among variables through CPTs based on samples retrieved from the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area. Therefore, through sensitivity analysis and probabilistic inference, the BBNs can reveal the relationship between landscape functions and further elucidate the driving mechanism. Additionally, exploring the use of BBNs in the analysis of multifunctional interrelationships holds potential for broader applications.

(2) Study limitations

While the BBNs are valuable for analyzing multifunctional trade-offs, synergies and driving mechanisms, they exhibit limitations. The BBNs require the definition of finite states for nodes and discretization of empirical data inputs, leading to information loss22. The number of network nodes and complexity of the structure should be constrained within certain limits, which significantly restricts the expression of landscape multifunctional relationships via BBNs15. Additionally, the actual landscape ecological process is complex and challenging to simulate thoroughly. For instance, landscape function assessment based on land use types often overlooks the spatial heterogeneity of these types, limiting the exploration of driving mechanisms and resource allocation optimization through BBNs. It is challenging to analyze landscape functional relationships in detail and comprehensively consider the varying influences of different factors on individual functions and multifunction.

Summary

Taking the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area as the study area, this study conducted a quantitative assessment of 5 landscape functions (RC, FP, HM, WC and LA) in 2022 to analyze the spatial distribution pattern of landscape multifunctionality. Furthermore, the BBNs model is constructed by combining landscape multifunction with Bayesian net network. Based on the trade-off and synergy relationship of landscape multifunction and scenario analysis, this paper discusses the driving mechanism of the trade-off and synergy of landscape multifunction. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

From the perspective of spatial distribution characteristics, the RC and FP of the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area show a spatial pattern of high in the northeast plain area and coastal area, low in the northwest and southwest mountains and hills area. The WC, HM and LA show a spatial pattern of high in northwest and southwest mountains and hills area, low in northeast plain and coastal area.

-

(2)

The supply of landscape multi-functions in Zhejiang Greater Bay Area shows high spatial heterogeneity, with 91.26% of the areas providing two or more landscape functions at the same time. Multifunctional diversity varies across land use and cover types.

-

(3)

From the perspective of the trade-synergy relationship, HM, WC and LA are synergistic. The relationships between RC and WC, FP and HM, and FP and LA are trade-offs.

-

(4)

According to the results of scenario analysis, LU and NDVI are the main factors affecting the synergistic relationship of landscape multifunctional. PD and SL are the main factors affecting the trade-off relationship. It is found that different driving factors produce the same synergy (or trade-off) in different states, while the same driving factors will cause different synergy (or trade-off) in different states.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The original data for this study are included in supplementary information files.

References

Wei, M. & Li., S. H.,. Research on the measurement of high-quality development level of Chinese economy in the new era. Quant. Econ. Tech. Econ. Res. 35(11), 3–20 (2018).

Peng, J., Hu, X. & Qiu, S. Multifunctional landscapes identification and associated development zoning in mountainous area. Sci. Total Environ. 660(10), 765–775 (2019).

Wu, J. G. Landscape sustainability science: Ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 28(6), 999–1023 (2013).

Liang, X., Jin, X., Han, B. & Sun, R. Landscape multifunctionality change in rapidly urbanized areas of the Yangtze River Delta: A case study of Suzhou City. Prog. Geogr. 40, 207–219 (2021).

Hölting, L., Beckmann, M., Volk, M. & Cord, A.-F. Multifunctionality assessments—More than assessing multiple ecosystem functions and services? A quantitative literature review. Ecol. Indic. 103, 226–235 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Fu, B. Landscape multifunctionality: Concept clarification. Recent progress, and frontier issues. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39(8), 2645–2654 (2019).

García, M.-M., Bieling, C., Hart, A. & Plieninger, T. Integrated landscape initiatives in Europe: Multi-sector collaboration in multi-functional landscapes. Land Use Policy 58, 43–53 (2016).

Peter, B., Mederly, P., Zita, I., Milena, M. & Magdaléna, B. Perception of ecosystem services in constituting multifunctional landscapes in Slovakia. Land 9 (2020).

Stürck, J. & Verburg, P.-H. Multifunctionality at what scale? A landscape multifunctionality assessment for the European Union under conditions of land use change. Landsc. Ecol. 32(3), 481–500 (2017).

Neyret, M., Peter, S. & Le, P.-G. Landscape management strategies for multifunctionality and social equity. Nat. Sustain. 6, 391–403 (2023).

Duncan, J.M.-A., Haworth, B. & Boruff, B. Managing multifunctional landscapes: Local insights from a Pacific Island country context. J. Environ. Manag. 260, 109692 (2020).

Grass, I., Kubitza, C. & Krishna, V. V. Trade-offs between multifunctionality and profit in tropical smallholder landscapes. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1186 (2020).

Navalho, I., Alegria, C., Natália, R. & Luís, Q.-N. Mapping forest landscape multifunctionality using multicriteria spatial analysis. Floresta e Ambiente 26(2), 20170702 (2019).

Peng, J., Lv, H. L., Liu, Y. X., Chen, X. & Hu, X.-X. International research progress and perspectives on multifunctional landscape. Adv. Earth Sci. 30(4), 465–476 (2015).

Feng, Z., Jin, X. & Chen, T. Understanding trade-offs and synergies of ecosystem services to support the decision-making in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Land Use Policy 106, 105446 (2021).

Mastrangelo, M. E. & Weyland, F. Concepts and methods for landscape multifunctionality and a unifying framework based on ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 29(2), 345–358 (2014).

Renard, D., Rhemtulla, J. M. & Bennett, E. M. Historical dynamics in ecosystem service bundles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112(43), 13411–13416 (2015).

Butler, J. R., Wong, G. Y. & Metcalfe, D. J. An analysis of trade-offs between multiple ecosystem services and stakeholders linked to land use and water quality management in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 180, 176–191 (2013).

Peng, J., Chen, X. & Liu, Y. Spatial identification of multifunctional landscapes and associated influencing factors in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. Appl. Geogr. 74, 170–181 (2016).

Pan, N. et al. Spatial differentiation and driving mechanisms in ecosystem service value of arid region: A case study in the middle and lower reaches of Shule River Basin, NW China. J. Clean. Prod. 319, 128718 (2021).

Madrigal-Martínez, S. & Miralles i García, J. L. Land-change dynamics and ecosystem service trends across the central high-Andean Puna. Sci. Rep. 9, 9688 (2019).

Landuyt, D., Broekx, S. & Goethals, P. L. Bayesian belief networks to analyse trade-offs among ecosystem services at the regional scale. Ecol. Indic. 71, 327–335 (2016).

Barton, D. N., Benjamin, T. & Cerdan, C. R. Assessing ecosystem services from multifunctional trees in pastures using Bayesian belief networks. Ecosyst. Serv. 18, 165–174 (2016).

Zeng, L., Li, J. & Li, T. Optimizing spatial patterns of water conservation ecosystem service based on Bayesian belief networks. Acta Geogr. Sin. 73(9), 1809–1822 (2018).

Dang, K. B., Windhorst, W. & Burkhard, B. A Bayesian Belief Network-based approach to link ecosystem functions with rice provisioning ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 41, 30–44 (2019).

Gonzalez-Redin, J., Luque, S., Poggio, L., Smith, R. & Gimona, A. Spatial Bayesian belief networks as a planning decision tool for mapping ecosystem services trade-offs on forested landscapes. Environ. Res. 144, 15–26 (2016).

Cui, W. L., Chen, M. Y. & Zhong, H. Y. Spatial differentiation and differentiated management of ecological security in the Bay Area based on ESDA and GA: A case study of the Zhejiang Greater Bay Area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 43(5), 2074–2087 (2023).

Bao, S., Cui, W. & Yang, F. Future land use prediction and optimization strategy of Zhejiang Greater Bay Area coupled with ecological security multi-scenario pattern. PLoS One 19(4), e0291570 (2024).

de Groot, R. Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multifunctional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 75(3/4), 175–186 (2006).

Frank, S., Fürst, C., Koschke, L., Witt, A. & Makeschin, F. Assessment of landscape aesthetics—Validation of a landscape metrics-based assessment by visual estimation of the scenic beauty. Ecol. Indic. 32, 222–231 (2013).

Li, G. D. & Fang, C. L. Quantitative function identification and analysis of urban ecological-production-living spaces. Acta Geogr. Sin. 71(1), 49–65 (2016).

Zeng, C. Q., Zhou, Y. & Wang, S. X. Population spatialization in China based on night-time imagery and land use data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32(24), 9599–9620 (2011).

Schirpke, U., Tasser, E. & Tappeiner, U. Predicting scenic beauty of mountain regions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 111(1), 1–12 (2013).

Sahraoui, Y., Clauzel, C. & Foltête, J. C. Spatial modelling of landscape aesthetic potential in urban-rural fringes. J. Environ. Manag. 181, 623–636 (2016).

Sharp, R., Tallis, H. T. & Ricketts, T. InVEST 3.2.0 user’s guide (Stanford University, University of Minnesota, the Nature Conservancy, and World Wildlife Fund, 2015).

Tenerelli, P., Püffel, C. & Luque, S. Spatial assessment of aesthetic services in a complex mountain region: Combining visual landscape properties with crowdsourced geographic information. Landsc. Ecol. 32(5), 1097–1115 (2017).

Pearl, J. Probabilistic reasoning in intelligent systems-networks of plausible inference. Morgan Kaufmann 48(1), 117–124 (1988).

Yue, W., Xia, H. & Wu, T. Spatio-temporal evolution of habitat quality and ecological red line assessment in Zhejiang province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 42(15), 6406–6417 (2022).

Wang, X., Peng, J., Luo, Y., Qiu, S. & Dong, J. Exploring social-ecological impacts on trade-offs and synergies among ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 197 (2022).

Hao, R., Yu, D., Sun, Y. & Shi, M. The features and influential factors of interactions among ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 101, 770–779 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Zhejiang Philosophy and Social Science Project (24NDQN058YB), Hangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Project (Z22JC097).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft. S.W.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review. S.C.: Visualization, Writing—editing. C.W.: Data curation, Software. F.X.: Data curation. All have agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Wu, S., Chen, S. et al. Understanding the trade-off and synergy effects of landscape multifunctional and its driving mechanism in rapidly urbanizing areas. Sci Rep 15, 25087 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99579-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99579-4