Abstract

There are abundant mulberry germplasm resources in China. Generally, in order to better utilize these resources, a comprehensive evaluation is conducted, among which the evaluation of photosynthetic capacity is an important aspect. To evaluate the photosynthetic characteristics of mulberry trees with different ploidy levels, which determine the number of chromosome sets in a cell or organism, we compared the microstructural features and transcriptomes of triploid and diploid mulberry trees. Haploid (n) means having one set of chromosomes, diploid (2n) has two sets, triploid (3n) has three sets, and so on. We compared the microstructural features and transcriptomes of triploid and diploid mulberry trees. In this study, the photosynthetic rates (Pn) of ‘guisang6hao’ (hereinafter referred to as GS6, 2n = 3x = 42) were 1.2 times that of ‘guisangyou12’(hereinafter referred to as GSY12, 2n = 2x = 28). Here, GS6 and GSY12 are abbreviations for the two mulberry varieties. The leaf thickness, main vein thickness, epidermal thickness, palisade tissue thickness, spongy tissue thickness and lower epidermal stomatal density of GS6 were greater than those of GSY12. Additionally, the transcriptome characteristics of GS6 and GSY12 were characterised by Illumina Novaseq 6000 and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were significantly enriched in photosynthesis. Four differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) related to photosynthesis were identified, playing key roles in chlorophyll metabolism and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms. The above results indicated that an increase in the ploidy level enhanced the photosynthetic capacity and utilisation of light energy, as well as the accumulation of chlorophyll content, of triploid mulberry trees. This study provides a technical and theoretical basis for germplasm innovation and the genetic improvement of mulberry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mulberry (Morus spp.) is an economically important crop, primarily cultivated for its leaves, which serve as the main feed for silkworms (Bombyx mori L.) and are essential for sericulture. Mulberry leaves also have high medicinal and nutritional value and are listed as medicinal and edible varieties by the Ministry of Health 1,2,3,4. A high yield of mulberry leaves is necessary for the vigorous development of the sericulture industry. The photosynthesis of higher plants is the foundation for their production5,6. Therefore, studying the characteristics of plant photosynthesis and exploring the mechanisms that promote high light efficiency are of great significance in both theory and practice.

Previous studies on mulberry photosynthesis have mostly focused on the effects of stress, fertilisation and cultivation on photosynthetic characteristics7,8,9,10. In recent years, with the rapid development of high-speed sequencing technology, an increasing volume of work has focused on analysing the genes and gene expression characteristics that are involved in differences in the photosynthetic characteristics of different mulberry varieties via the transcriptome, proteome and RNA-Seq11,12,13,14,15. However, most of these studies have focused on the analysis of photosynthetic characteristics under different stresses or propagation methods, there are few reports comparing the photosynthetic characteristics and key gene expression regulation of mulberry varieties with different ploidy levels.

Mulberry trees have complex genetics and chromosomal ploidy16. Polyploidy occurs when the entire chromosome set is multiplied and this variation is heritable17,18. Polyploids are classified into two types: allopolyploids, which result from interspecific hybridization, and autopolyploids, which arise from genome duplication within the same species19,20. Polyploid plants typically exhibit a larger overall size, well-developed organs and tissues—such as thicker stems, larger leaves, larger flowers and larger fruits—and higher nutrient content such as sugars and proteins, resulting in higher yields21,22. These characteristics make polyploid plants highly attractive in agricultural breeding. GS6 (2n = 3x = 42) and GSY12 (2n = 2x = 28) are the main high-yield mulberry varieties promoted in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region which is located in southern China and is a region with rich ethnic culture and natural resources. Since 2006, Guangxi has ranked first in China in terms of mulberry orchard area. The area of mulberry orchards in the whole region is basically stable at around 3 million mu every year, accounting for about 25% of the national mulberry orchard area. GS6 is a hybrid combination, with parent combination, 7862 (♀) × Guiyou94168 (♂). 7862 is a diploid variety (2n = 2x = 28) introduced from the Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Guiyou94168 is a tetraploid variety (2n = 4x = 56), which was preserved at the Guangxi Sericulture Technology Promotion Station. GSY 12 is also a hybrid combination, with parent combination, Sha 2 (♀) × Gui 7722 (♂), and Sha 2(2n = 2x = 28) provided by the Agricultural Science Institute (ASI) of Shunde City, Guangdong Province. Gui 7722 (2n = 2x = 28) is an excellent strain selected from the F1 of Taiwan Qingpi X Lun 109 by the Guangxi Sericulture Technology Promotion Station. GS6 leaves exhibited significantly larger dimensions and thickness compared to GSY12, with a length by width of 30.2 cm × 27.3 cm and weight per square centimetre of GS6 leaves is 4.75 g·100 cm–2, respectively (P < 0.05). The length by width and weight per square centimetre of GSY12 leaves are 25.6 cm × 20.3 cm and 2.25 g·100 cm–2, respectively.

Transcriptome studies have shown that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across different ploidy levels in plants are significantly enriched in energy metabolism23,24. However, the mechanism of ploidy-related photosynthesis is still largely unclear. Therefore, this study explored the physiological and molecular mechanisms of photosynthesis in mulberry with different ploidy levels. A combination of transcriptome and metabolome techniques were used to compare the differences in photosynthesis between diploid and triploid mulberry trees and their microstructural differences were also analysed. These results enhance understanding of the regulation of photosynthesis in mulberry trees with different ploidy levels and provide a theoretical basis for future breeding work.

Results

Photosynthetic characteristics of GS6 and GSY12

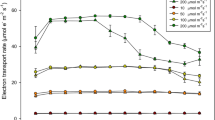

The measurements of the photosynthetic characteristics of mulberry leaves with different ploidy levels showed that the diurnal variation of Pn in GSY12 and GS6 leaves was bimodal, with a pronounced photosynthetic ‘midday rest’ phenomenon and with two peaks at 10:00 am and 14:00 pm. The peak Pn of GS6 leaves (19.42) was significantly higher than that of GSY12 (16.10) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). CO2 concentration (Ci) reached their peak at 8:00 am in both GS6 and GSY12, and then began to decline. Ci in GS6 was consistently higher than that in GSY12, reaching a significant level (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). The conductance (Gs) reached their peak at 8:00 am in both GS6 and GSY12 and their lowest values at 10:00 am. Gs in GS6 was consistently higher than that in GSY12, reaching a significant level (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). For transpiration rate (Tr), there was no significant difference in GS6 and GSY12 at 6:00 am (P > 0.05), while GS6 showed a higher significant difference than GSY12 at 8:00 am, and both reached their peak at 12:00 am (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). The curves of water utilization efficiency (WUE) in GS6 and GSY12 were consistent with the Pn curves, both showing a bimodal pattern with two peaks at 10:00 am and 14:00 pm. The peak WUE of GS6 leaves was higher than that of GSY12 leaves and the difference was significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E). The above results revealed that GS6 has stronger photosynthetic ability than GSY12.

Photosynthetic characteristics of GS6 and GSY12. (A) Pn curves for GS6 and GSY12. (B) Ci curves for GS6 and GSY12. (C) Gs curves for GS6 and GSY12. (D) Tr curves for GS6 and GSY12. (E) WUE curves for GS6 and GSY12. (F) Chlorophyll and carotenoid content of GS6 and GSY12. Pn: Net photosynthetic rate, Ci: intercellular CO2 concentration, Gs: stomatal conductance, Tr: transpiration rate, WUE: Water utilization rate. Leaves from positions 3–8 of GS6 and GSY12 were sampled every 2 h from 6:00 am to 4:00 pm. Pn, Ci, Gs, Tr were measured by LI—6400XT. WUE = Pn/Tr, with PPFD set at 1200 μmol·m−2·s−1. Each measurement had 3 biological replicates, results shown as means ± SE. The different normal letters are significantly different at P < 0.05. * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01) mark significant differences.

Chlorophyll and carotenoids participate in the absorption and transfer of light energy or cause primary photochemical reactions in photosynthesis. Figure 1F showed that the content of photosynthetic pigment differed between GSY12 and GS6, with highly significant differences in the total chlorophyll and chlorophyll a content (P < 0.01) and significant differences in carotenoid and chlorophyll b content (P < 0.05). This indicated that GS6 has a stronger ability to absorb light than GSY12.

Photosynthetic characteristics of GS6 and GSY12 mulberry leaves

Table 1 shows that GS6 had greater leaf length, width, and weight per square centimeter compared to GSY12. The leaf length of GS6 was 30.2 cm, which was 1.18 times that of GSY12 (25.6 cm), the leaf width of GS6 was 27.3 cm, which was 1.36 times that of GSY12 (20.03 cm) and the leaf weight of GS6 was 4.75 g·100 cm–2, which was 2.11 times that of GSY12 (2.25 g·100 cm–2).

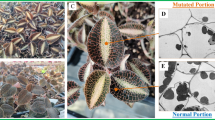

As shown in Table 2, the leaf thickness, upper and lower epidermal thickness, palisade tissue thickness, spongy tissue thickness, main vein thickness and stomatal density of GSY12 and GS6 all showed significant differences (P < 0.05). The structural thickness and stomatal density of GS6 were greater than those of GSY12 (Fig. 2A–D). The upper/lower epidermal cells of GS6 had a large volume, loose arrangement and irregular shapes, whereas the GSY12 epidermal cells were arranged tightly and had a more regular shape (Fig. 2A,B). The pore structure of GS6 was clear and most pores were open, whereas GSY12 had a uniform distribution of pores that were mostly closed (Fig. 2E,F).

Leaf structure characteristics of GS6 and GSY12. (A) mesophyll cross section of GSY12. (B) mesophyll cross section of GS6. (C) main vein cross section of GSY12. (D) main vein cross section of GS6. (E) Scanning electron microscopy image of mesophyll cells of GSY12. (F) Scanning electron microscopy image of mesophyll cells of GS6. UE: upper epidermal cells, PT: palisade tissue, ST: sponge tissue, LE: lower epidermal cells, MV: main veins, LV: leaf veins, GH: glandular hairs, CS: closed stomata, OS: open stomata.

Linear correlation between leaf structure and photosynthetic characteristics of GSY12 and GS6

The linear correlation between the leaf structure and photosynthetic characteristics of GSY12 and GS6 is shown in Table 3. The thickness, palisade tissue thickness, spongy tissue thickness and main vein thickness of GSY12 and GS6 leaves were significantly positively correlated with the maximum net photosynthetic rate (Pmax P < 0.01). The chlorophyll content and stomatal density were also significantly positively correlated with Pmax (P < 0.05), while pyropheophorbide a was significantly negatively correlated with Pmax.

Relationship analysis of GSY12 and GS6

In high-throughput sequencing analysis, the relationship among samples is determined by numerous variables, including gene expression, the distribution characteristics of reads, enrichment distribution of peaks, etc. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can reduce the complexity of data, so we can use PCA to identify outlier samples and distinguish sample clusters with high similarity. As shown in Fig. 3A, each group of samples and biologically duplicated samples clustered together, while the treatment groups were clustered in different regions, indicating good sample repeatability. Moreover, correlation analysis between biological replicates not only verifies whether the variations between biological replicates meet the expectations of experimental design, but also provides basic reference for differential gene analysis. As shown in Fig. 3B, the correlation coefficient of each group of samples and biologically duplicated samples is to 1, while the correlation coefficient between treatment groups were significantly lower than that within groups, indicating the randomness and repeatability of the sampling.

Correlation analysis between samples GS6 and GSY12. (A) PCA analysis between GS6 and GSY12. (B) Correlation heatmap between GS6 and GSY12. The different colored squares represent the high or low correlation between the two samples. The distance between each sample point represents the distance of the sample. The closer the distance, the higher the similarity between the samples. The horizontal axis represents the contribution of Principal Component 1 (PC1) to the discriminative samples in the two-dimensional graph, while the vertical axis represents the contribution of Principal Component 2 (PC2) to the discriminative samples in the two-dimensional graph.

Transcriptome characteristics of GS6 and GSY12

The collection of full-length transcriptome data from six samples was based on the second-generation sequencing platform of Illumina Novaseq 6000 (The raw sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Datasets, bioproject number is PRJNA1137124). By filtering the original data, a total of 44.22 Gb of clean reads were obtained, with each sample having more than 7.37 Gb of clean reads and a Q30 base percentage of more than 90% (Supplementary Table 1). Sequence alignment was performed between the clean reads of each sample and the designated reference genome, with alignment rates ranging from 76.2% to 78.32% (Supplementary Table 2). This was satisfactory for the annotation of subsequent genes (mapping > 65%). When mapping the transcript and the reference genome, the reads aligned to the unannotated region of the reference genome. gtf file were defined as new genes. A total of 47,156 genes were assembled, including 2707 new genes (Supplementary Table 3).

Dynamics of photosynthesis-related gene expression in GS6 and GSY12 mulberry

The phenotypic differences between mulberry GS6 and GSY12 may arise from differences in transcriptome dynamics. Compared with GSY12, GS6 had a total of 4511 DEGs (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.05, fold change [FC] ≥ 2), including 1821 upregulated genes and 2690 downregulated genes (Fig. 4A). To further explore the biological functions of the DEGs, the GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed. Interestingly, the first two entries in the GO enrichment results were related to photosynthesis, chlorophyll biosynthetic process and photosynthesis, and light harvesting. These results included 25 DEGs, all of which had significantly higher expression levels in GS6 than in GSY12 (Fig. 4B). Additionally, there were three entries related to photosynthesis in the top five KEGG enrichment results, including photosynthesis, photosynthesis—antenna proteins, and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (Fig. 4C). Among the 73 DEGs, 64 genes had significantly higher expression levels in GS6 than in GSY12 (Fig. 5). These included nine photosystem I reaction centre subunit genes, including those relating to photosystem I reaction centre subunits II–VI, XI, PSAK, N and O. Eleven genes were associated with the photosystem II reaction centre, including with oxygen-evolving enhancer proteins 1–3, PSBP-like protein 1, photosynthetic NDH subunit of lumenal locations 2 and 3, photosystem II 22 kDa protein, photosystem II reaction centre W and PSB28 protein, and photosystem II core complex protein PSBY. Six genes were associated with photosynthetic electron transfer, including with plastocyanin, ferredoxin, ferredoxin-NADP reductase and cytochrome c6. There were thirteen light-harvesting complex genes, including those related to chlorophyll a-b binding proteins 3, 5, 6, 8, P4 and a series of other chlorophyll a-b binding proteins. In addition, twenty genes involved in carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms, including those related to phosphoribulokinase, ribose-5-phosphate isomerase 3 and 4, plastocyanin, transketolase, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and a series of other phosphatases. Among these, the gene that encodes plastocyanin—a protein containing copper atoms that is located on the inner surface of the thylakoid membrane and is an important member of the photosynthetic chain—was upregulated by a significant 5.39-fold in GS6 compared with GSY12.

Identification and analysis of DEGs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12. (A) Number of up- and downregulated genes. DEGs: differentially expressed genes. The x—axis shows different comparison groups, and the y—axis shows the number of upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes/transcripts. (B) Bubble charts of the top 20 GO entries results for the most prominent DEGs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12. The vertical axis shows GO Term, and the horizontal axis shows Rich Factor (the ratio of enriched to annotated genes/transcripts in a GO term). Dot size represents the gene/transcript count in the GO Term, and dot color corresponds to Padjust ranges. The top 20 enrichment results with Padjust < 1 are displayed. Goatools is employed to analyze the DEGs for GO functions, using Fisher’s exact test. When P < 0.05, significant enrichment in a GO function is indicated. (C) Bubble charts of the top 20 KEGG enrichment results for the most prominent DEGs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12. The vertical axis labels the enriched pathways, and the horizontal axis shows the Rich factor (the ratio of enriched to annotated genes/transcripts). Dot size indicates the gene count in each pathway, and dot color shows different Padjust ranges. The top 20 enrichment results with Padjust < 1 are presented. R scripts are used to perform KEGG PATHWAY enrichment analysis on genes/transcripts in the gene set. If the adjusted P value (Padjust) is less than 0.05, there’s significant enrichment for that KEGG PATHWAY function.

Metabolome characteristics of GS6 and GSY12

In this study, a non‐targeted quantitative analysis of the metabolites in six samples was performed. As shown in Fig. 6A, each group of samples and biologically duplicated samples clustered together, while the treatment groups were clustered in different regions, indicating good sample repeatability. A total of 604 DEMs were identified in GS6 and GSY12, including 246 upregulated metabolites and 358 downregulated metabolites, respectively (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the metabolites in the GS6 and GSY12 strains showed specific expression patterns. The downregulated DEMs were mainly involved in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis and glycerophospholipid metabolism (Fig. 6C). The upregulated DEMs were closely related to purine metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms. Interestingly, unlike the enrichment of a large number of DEGs related to photosynthesis in the transcriptome, only one pathway related to photosynthesis was enriched in the upregulated DEMs, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (Fig. 6D). Among all DEMs, four significantly upregulated DEMs related to photosynthesis were enriched, including D-sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (Fig. 7A), malic acid (Fig. 7B), D-fructose 6-phosphate (Fig. 7C) and protochlorophyllide (Fig. 7D). Another metabolite, pyropheophorbide a—the intermediate degradation product of chlorophyll-a—was significantly downregulated in GS6 (Fig. 7E). This indicated that the stability of chlorophyll a in GS6 may be better than that in GSY12. In addition, we measured the contents of these five metabolites in GS6 and GSY12 using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and the results showed that there were differences in the content of the five metabolites between GS6 and GSY12 (P < 0.01) and the expression of these metabolites displayed patterns that were very similar to those of the abundance value from metabolome sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Identification and analysis of DEMs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12. (A) PCA analysis between GS6 and GSY12. (B) Number of up- and downregulated metabolites. (C) Bar charts of the KEGG enrichment results for the upregulated DEMs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12. (D) Bar charts of the KEGG enrichment results for the downregulated DEMs between two comparison groups: GS6 and GSY12.

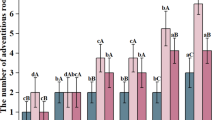

(A–D) Significantly upregulated DEMs related to photosynthesis: (A) D-sedoheptulose 7-phosphate, (B) Malic acid, (C) D-fructose 6-phosphate, (D) Protochlorophyllide and (E) Significantly downregulated DEM related to photosynthesis: pyropheophorbide a. The different normal letters are significantly different at P < 0.05. *means P < 0.05, **means P < 0.01.

Validation of gene expression using qRT-qPCR

Based on the preliminary results, ten genes related to the mulberry photosynthesis response were chosen for transcriptome sequencing validation by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8) and the primers were shown in supplementary Table 4. The qRT-PCR analysis results showed that all ten selected genes were differentially expressed between GS6 and GSY12 (P < 0.05) and the expression of these genes displayed patterns that were very similar to those of the TPM (transcripts per million reads) values from transcriptome sequencing under the corresponding treatments. The above results indicated that the RNA-seq data were reliable.

qRT-PCR verification of 10 genes related to photosynthesis pathways in GS6 and GSY12. OEE1: oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1, PSI-K: photosystem I reaction center subunit psaK, PSAD: photosystem I reaction center subunit II, PSI-N:photosystem I reaction center subunit N, PETC: cytochrome b6-f complex iron-sulfur subunit, ATPC: ATP synthase gamma chain’, chloroplastic, ATPD: ATP synthase delta chain’, chloroplastic, ATPG: ATP synthase subunit b’’, chloroplastic.

Discussion

The role of specialized leaf structures in enhancing photosynthesis

The photosynthetic rate curves at different periods revealed the photosynthetic characteristics of the mulberry leaves. Pmax represents the potential maximum net photosynthetic efficiency of plants, which is the photosynthetic rate at the light saturation point (LSP). The LSP represents the ability of plants to utilise strong light28,29,30. The Pmax value of GS6 was higher than that of GSY12 and the difference was significant (P < 0.05), indicating that, under the same growth environment, the photosynthetic capacity of GS6 was stronger than that of GSY12 (Fig. 1A).

Highly specialised leaf structures contribute to photosynthesis. For example, the epidermal cells of leaves are completely transparent to visible light, while the flat and convex epidermal cells can gather more light into photosynthetic cells, thereby increasing the photon flux density (PPFD) reaching chloroplasts to several times that of peripheral light31,32. The palisade tissue cells of plants are like light tubes, with very high chlorophyll content in the outermost layer, which can increase the depth of direct light transmission. The palisade tissue of GS6 was arranged in a columnar parallel pattern and was significantly thicker than in GSY12 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A, B). This result was similar to the research findings that tetraploid plants in Lolium have longer mesophyll cells, including palisade tissue cells, than diploid plants33. The main function of palisade tissue cells is to carry out photosynthesis. Through their close arrangement and containing a large number of chloroplasts, they can maximize light absorption and energy production. Moreover, palisade cells can control the production of a kind of ultraviolet-absorbing molecule, which reduces the destructive impact of ultraviolet rays on photosynthesis, indicating that the palisade tissue plays a role in protecting the normal progress of photosynthesis34. Spongy tissue, due to its irregular cell shapes and being surrounded by air bubbles, provides a large air–water interface for scattered light. Therefore, light can undergo multiple reflections at the interface between cells and gases, greatly extending the path of light transmission and increasing the possibility of light energy being absorbed. Compared to GSY12, the spongy tissue cells of GS6 were arranged more loosely and had larger air bubbles surrounding them, resulting in more air–water interfaces (Fig. 2A,B). Therefore, GS6 would be able to absorb and utilise light more evenly, leading to better photosynthetic performance. Generally, the thicker the main vein of a leaf, the higher the efficiency of water transport within the leaf. In this study, the main vein thickness of GS6 was higher than that of GSY12 (Fig. 2C,D), indicating a higher water use level in GS6 leaves. The photosynthetic rate of plant leaves is controlled by the stomatal cells of the leaf epidermis35. A comparison of the differences in epidermal stomata between GS6 and GSY12 leaves revealed that GS6 has more stomata per unit area, a higher degree of openness during the same period, and denser distribution (Fig. 2E,F). Stomatal openness directly regulates CO2 availability, influencing the photosynthetic rate of leaves36,37,38. Therefore, the higher stomatal density in GS6 was beneficial for the smooth entry of photosynthetic substrate CO2 into the leaves, thereby enhancing their photosynthetic rate. Together, these results suggest that the photosynthetic capacity of mulberry trees is closely related to the structural characteristics of their leaves and that GS6 may have a stronger adaptability to light and photosynthetic light utilisation ability than GSY12.

The increase in gene dosage related to photosynthesis promotes the photosynthetic capacity and utilisation of light energy in GS6

Generally, compared to diploid plants, photosynthesis-related genes are upregulated in polyploid plants, as has been demonstrated in many species such as Arabidopsis, rice, radish, soybean, orchid etc39,40,41,42,43,44. In this study, there were 73 DEGs related to photosynthesis and chlorophyll (Fig. 4A). Sixty-four DEGs that are involved in photosynthesis—including genes specifically expressed in photosynthetic organisms, cytochrome genes and photosystem-related genes—all had significantly higher expression levels in GS6 than in GSY12 (Fig. 4B,C). Several important genes were substantially upregulated in GS6, such as the photosystem I reaction centre subunit II-VI and XI, photosystem II reaction centre W, PSB28, psbY and a series of chlorophyll a-b binding proteins (Fig. 5). Chlorophyll plays an irreplaceable role in photosynthesis and is crucial for plants to absorb solar energy, produce organic matter and release oxygen45. In this study, the chlorophyll content in GS6 was much higher than that in GSY12 (Fig. 1B). This was consistent with the up-regulation of the majority of the chlorophyll biosynthesis genes in GS6.

Photosynthesis is divided into two stages, the light reaction and the dark reaction. The dark reaction process is also known as the Calvin cycle, which is the process by which green plants fix CO2 in the atmosphere and convert it into carbohydrates, providing necessary carbon compounds for plant growth and development46. RuBisco is typically considered a key limiting enzyme for photosynthetic carbon fixation47. However, the latest research has found that the regeneration ability of carbon skeleton molecule ribulose-1,5-diphosphate (RuBP) is influenced by sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), therefore, SBPase is the key enzyme for RuBP formation and maintaining the carbon cycle balance48,49,50. Additionally, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) in plants has a similar structure to SBPase, these are homologous but are functionally differentiated during evolution, with FBPase mainly affecting starch synthesis and the carbon metabolism balance51,52,53. In this study, twenty genes involved in carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms had significantly higher expression levels in GS6 than in GSY12, including sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, which is the key enzyme responsible for the regeneration process of RuBP54, Fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) and a series of other phosphatases(Fig. 5). The upregulation of genes encoding these enzymes promotes the CO2 fixation efficiency of Calvin Benson cycle (CBC), ultimately leading to an increase in plant photosynthetic capacity and biomass55,56. These results were also consistent with the results of metabolomics analysis. For example, the upregulation of genes encoding FBPase resulted in more D-fructose-6-phosphate (Fig. 7C) production in GS6 than in GSY12. The above results indicated that GS6 had a higher carbon fixation ability than GSY12, thereby improving the polyploid plant’s photosynthetic capacity, which may be the reason for the more vigorous growth and development of polyploid plants. In addition, the content of pyropheophorbide a in GS6 was significantly lower than GSY12 (Fig. 7E). Pyropheophorbide a is one of the degradation intermediates of chlorophyll a, and its content changes with the degradation of chlorophyll during the chlorophyll degradation process. If under certain conditions, chlorophyll stability is poor and degradation is prone to occur, then the content of pyropheophorbide a may increase with time. On the contrary, if chlorophyll stability is good and degradation is slow, the content of pyrophosphate a is relatively low and the change is small. Therefore, by monitoring the changes in the content of chlorophyllin a in deforested leaves, the stability of chlorophyll can be indirectly reflected. This indicates that the stability of chlorophyll a in GS6 may be better than that in GSY2. But there are also certain limitations. The degradation pathway of chlorophyll is relatively complex. In addition to the pathway of pyropheophorbide a, there may be other pathways and multiple intermediate products. Measuring the content of pyropheophorbide a alone cannot fully and accurately reflect the overall degradation and stability of chlorophyll, and may overlook the influence of other degradation products. So the determination of pyropheophorbide a content can serve as a reference indicator for evaluating chlorophyll stability, but it needs to be combined with other methods and factors for comprehensive judgment in order to obtain more accurate results.

Conclusions

In this study, the leaf microstructure, transcriptome and metabolome in GS6 and GSY12 mulberry plants were compared. larger leaf dimensions and a thicker leaf microstructure were observed in GS6. Additionally, GS6 had more stomata per unit area, a higher degree of stomatal openness during the same period and, denser distribution. Significant transcriptional changes were observed in genes associated with chlorophyll biosynthesis, photosystems, and carbon fixation in GS6. For metabolome, four significantly upregulated DEMs related to photosynthesis were enriched, including D-sedoheptulose-7-phosphate, malic acid, D-fructose 6-phosphate and protochlorophyllide.These characteristics suggest that when selecting plants with these features as parents in breeding, it is expected to cultivate mulberry varieties with higher photosynthesis efficiency, increase biomass accumulation, thereby improving the yield of mulberry leaves, providing more sufficient feed resources for the sericulture industry, and may also bring economic benefits in other industries that use mulberry as raw materials (such as pharmaceuticals, food, etc.) due to the increased yield of raw materials. Moreover, the studies on the transcriptome and metabolome of GS6 and GSY12 mulberry plants have identified genes and metabolites that are closely associated with excellent traits (such as the improvement of photosynthetic efficiency), providing precise targets for subsequent molecular marker-assisted breeding. Through modern biotechnology means such as gene editing, these excellent genes can be introduced into other mulberry varieties to accelerate the breeding process of excellent varieties, precisely improve mulberry varieties, improve breeding efficiency and effectiveness, and obtain new mulberry strains with ideal photosynthetic performance and other excellent agronomic traits more quickly. Although GS6 exhibits many excellent photosynthesis-related traits, these traits may change under the influence of environmental factors during the breeding process, which poses a challenge to the cultivation of mulberry varieties that can adapt to different environments widely and stably exhibit excellent photosynthetic performance.

Methods

Plant materials and cultivation

The triploid mulberry variety GS6 and diploid mulberry variety GSY12 are the main varieties promoted in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and their seeds are preserved by the Sericulture Technology Promotion Station. In the winter of 2022, a batch of seeds with a good germination rate was sown into a potted barrel and placed in a transparent greenhouse, where it underwent normal water and fertiliser management. In early September 2023, leaves from positions 3–5 of six well-growing mulberry plants were collected. The samples were stored in liquid nitrogen for transcriptome and metabolome sequencing. Each group was analysed in three biological replicates.

Sample preparation steps for scanning electron microscopy and microscopy

In early August 2023, the leaves at positions 2–4 of 3 pots of mulberry potted plants with good growth and trend were collected and the leaf samples were cut into 2 × 5 mm strips, fixed with glutaraldehyde (pH 6.8) and dehydrated with 50, 70, 90, 100 and 100% ethanol, sequentially. Next, the samples were placed in a mixture of ethanol and tert-butanol (1,1, v/v) for 15 min, which was then replaced with pure tert-butanol and frozen at –20 ℃ for 30 min. After drying and gold-plating the samples, they were observed and imaged using HT7800/HT7700 transmission electron microscopy and the magnification range used during imaging was 200 × or 500 × .

The leaf samples (The collection method is the same as above) were fixed in a solution of formaldehyde/acetic acid/ethanol for more than 24 h. After stepwise dehydration with ethanol, transparency treatment with xylene, waxing and embedding, the samples were subjected to unfolding, pasting, dewaxing, stepwise rehydration and then staining with 0.5% toluidine blue O for 3 min to seal the film. Finally, the samples were observed and photographed using an Eclipse Ci-L light microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Determination of growth parameters and microstructural characteristic parameters

Twenty fully developed leaves from the second to fourth sections of the seedlings were selected and their growth indicators, including leaf length, width and mass per 100 cm2 were measured.

An Eclipse Ci-L photography microscope (Nikon, Japan) was used to magnify the target areas of leaf tissue for 40 × and 200 × imaging. During imaging, the proportion of tissue in the entire field of view was maximised to ensure consistent background light for each photo. After imaging, Image Pro Plus 6.0 analysis software (Media Cybemetics, U.S.A) was used to measure the thickness of the leaves, palisade tissue, spongy tissue, upper epidermis, lower epidermis and main vein.

Measurement of photosynthetic parameters

Using the LI-6400XT (LI-COR, USA) portable photosynthetic analyser, the net photosynthetic rate (Pn) of GSY12 and GS6 was measured. Three plants with equal growth potential of GS6 and GSY12 were selected to measure the net photosynthetic rate. Every 2.0 h from 6;00 am to 16;00 pm, leaves at positions 3–8 were chosen for measurement. Simultaneously perform gas exchange parameters, intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), stomatal conductivity (Gs), transpiration rate (Tr), and water use efficiency (WUE) measurement, WUE = Pn/Tr, Set Photosynthetic photo flux density (PPFD) to 1200 μmol · m−2 · s−1. Parameter settings, air flow rate of 500 μmol s−1, CO2 flow rate of 400 μmol mol−1, and a head light source intensity of 750 μmol m−2 s−1. Fitting calculation of maximum net photosynthetic rate (Pmax) using a non right angled hyperbolas modified model57. Each measurement was conducted in three biological replicates and the average value was calculated.

Determination of chlorophyll content

The leaf samples were ground into powder under liquid nitrogen and extracted by adding 3.0 mL of 95% ethanol to the ice bath. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min and the supernatant was used for the determination of chlorophyll content. An aliquot of 0.5 mL was diluted to 2 mL with 95% ethanol and its absorbance was measured at 470, 649 and 665 nm using a microplate reader. The equations Ca = 13.95 × D665 – 6.88 × D649 and Cb = 24.96 × D649–7.32 × D665 were used to calculate the content of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b (mg·L–1), the concentration of total chlorophyll was obtained from the sum of Ca and Cb.

RNA-seq of mulberry leaves

For transcriptome sequencing, three biological replicates of each group were prepared. TRIzol® reagent was utilised to isolate the total RNA from the leaf tissue according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of total RNA were determined using the 5300 Bioanalyser (Agilent) and ND-2000 (NanoDrop Technologies), respectively. To construct a reliable sequencing library, 1 μg of high-quality RNA sample (OD260/280 = 1.8−2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0, RIN ≥ 6.5, 28S,18S ≥ 1.0, > 1 μg) was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (San Diego, CA, Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China). The sequences in the library were prepared at a 2 × 150 bp read length. Sequencing was performed using Illumina Novaseq 6000. The raw reads were filtered using fastp with default parameters and we have uploaded the raw transcriptome data to a public database (NCBI), and a BioProject number has been provided (PRJNA1137124).

The HISAT2 (http,//ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml) was used to align the clean data to the mulberry reference genome58, then RSEM software was used to calculate gene expression levels based the alignment file. The StringTie software (http,//ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/) was used to concatenate the mapped reads and compare them with the original genome annotation information to search for previously unannotated transcription regions and discover new transcripts and genes. Firstly, the overlapping reads are assembled into superreads. Then, the superreads are aligned to the reference genome and a graph of the splice site is constructed. Finally, the pathways with high read coverage are preserved and assembled together to form a transcript. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the DEseq2 program with the criterion of |Fold Change|≥ 2 and FDR < 0.05 (the commonly used thresholds). The FDR is an indicator used to control false positive results in multiple hypothesis testing. By controlling the FDR at a level of < 0.05, it can ensure that the differentially expressed genes screened out have a relatively high credibility, that is, only less than 5% of the genes judged as differentially expressed may be false positives due to random errors. Simultaneously, the genes were annotated for function using Gene ontology (GO) (http//www.geneontology.org), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway (http//www.genome.jp/kegg/). Perform functional enrichment analysis on genes/transcripts in the gene set, including GO enrichment and KEGG enrichment. Use the software Goatools to conduct GO enrichment analysis on the genes in the gene set, so as to obtain which GO functions the genes in this gene set mainly possess. The method used is Fisher’s exact test. When the adjusted P value (Padjust) < 0.05, it is considered that there is a significant enrichment situation for this GO function. Use R scripts to conduct KEGG PATHWAY enrichment analysis on the genes/transcripts in the gene set. The calculation principle is the same as that of the GO functional enrichment analysis. When the adjusted P value (Padjust) < 0.05, it is considered that there is a significant enrichment situation for this KEGG PATHWAY function.

Metabolome measurement

For metabolome analysis, the metabolites were extracted from the leaves of drought-stressed plant samples and then analysed using an LC–MS/MS system (UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X system, Thermo, USA) with an ACQUITY HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.8 μm, Waters, USA). The mobile phase passed through the column at a flow rate of 0.40 mL·min–1 at 40 °C. Subsequently, the mass spectrometric data were collected using a UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X Mass Spectrometer (Thermo, USA). Data were collected in the Data Dependent Acquisition (DDA) mode.

The original LC/MS data file was imported into Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) and then exported as a three-dimensional data matrix in CSV format. The metabolites were identified by searching in HMDB (http//www.hmdb.ca/), Metlin (http//metlin.scripps.edu/) and Majorbio databases. Then, the obtained metabolites matrix was submitted to the Majorbio cloud platform (http//cloud.majorbio.com) for subsequent data analysis. Briefly, the “ropls” (Version 1.6.2) package in R Studio was used to conduct the principal component analysis (PCA) and the orthogonal least partial squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). The variable importance (VIP) obtained from the OPLS-DA model and the p-value generated by Student’s t-test were utilised to evaluate the significance. The cut-off values were set as VIP ≥ 1 and P < 0.0559. The DEMs of the two groups were submitted into the KEGG database for mapping of their biochemical pathways.

Quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

The RNAiso Plus kit (Takara, Japan) was utilised to isolate the total RNA. Then, 1000 ng of total RNA was used to perform reverse transcription using the Prime Script RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan). 2 μL of the synthesised first-strand cDNA was used as a template. The SYBR Premix reagent (Toyobo, Japan) was utilised for qRT-PCR. The reactions were performed on an Applied Biosystems Step One Plus RealTime PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). Cycle conditions were as follows, pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 15 s, 72 °C 20 s, 38 cycles, followed by a standard melting curve analysis. Mulberry MaACT3 (GenBank accession number, HQ163775.1) gene was used as the reference gene. The expression of the ten genes were processed using the 2−∆∆CT method60. ΔCt = (CtGS6/GSY12 – CtA3); ΔΔCt = (ΔCtGS6 – ΔCtGSY12). “2−ΔΔCt GSY12 value ≈ 1”. \(Fold change = \frac{{2^{ - \Delta \Delta Ct} GS6 value}}{{2^{ - \Delta \Delta C} GSY12 value}}\). Primers were designed using Primer 5.0 software (Supplementary Table 4). Three independent experiments were conducted and three technical replicates for each sample were required.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2013 and IBM SPSS Statistics (v25.0, IBM,USA)61. DEGs and DEMs were analyzed by One-way ANOVA at P < 0.05. Values were presented as means ± standard error (SE). The data used for One-way ANOVA all satisfy normality and homogeneity of variance. Shapiro—Wilk test was used to test the normal distribution of data, and Levene test was used to test the homogeneity of variance (P > 0.05).

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. The transcriptome data generated during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Datasets, bioproject number is PRJNA1137124.

References

Jan, B. et al. Nutritional constituents of mulberry and their potential applications in food and pharmaceuticals. Rev. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 3909–3921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.056 (2021).

Lu, N. et al. Biosynthetic pathways and related genes regulation of bioactive ingredients in mulberry leaves. Plant Signal Behav. 18, 2287881. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2023.2287881 (2023).

Chen, C., Mohamad Razali, U. H., Saikim, F. H., Mahyudin, A. & Mohd Noor, N. Q. I. Morus alba L. plant: Bioactive compounds and potential as a functional food ingredient. Foods 10(3), 689 (2021).

Mo, J. et al. Mulberry anthocyanins ameliorate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal barrier function and modulating gut microbiota. Antioxidants 11(9), 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091674 (2022).

Evans, J. R. & Clarke, V. C. The nitrogen cost of photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery366 (2019).

Hosali, R. & Murthy, C. To analyse the cost of mulberry and cocoon production in Haveri district. Int. J. Commer. Bus. Manag. 8, 58–63 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Responses of photosynthesis and antioxidants to simulated acid rain in mulberry seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 172, 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.13320 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Physiological and proteomic analysis of seed germination under salt stress in mulberry. Front Biosci. 28, 49 (2023).

Rao, L., Li, S. & Cui, X. Leaf morphology and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of mulberry seedlings under waterlogging stress. Sci. Rep. 11, 13379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92782-z (2021).

Zhang, X. L., Zhang, Q. Q., Xu, T. X., Ling, F. & Sun, G. Y. Amelioration of chemical and organic fertilizer on photo-inhibition of PSII at photosynthetic noon-break in mulberry leaves grew in saline-sodic soils. Pratacult. Sci. 32, 745–753 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Screening and verification of photosynthesis and chloroplast-related genes in mulberry by comparative RNA-seq and virus-induced gene silencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158620 (2022).

Peng, X. J., Teng, L. H., Yan, X. Q., Zhao, M. L. & Shen, S. H. The cold responsive mechanism of the paper mulberry, decreased photosynthesis capacity and increased starch accumulation. BMC Genomics 16, 898. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-2047-6 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Physiological and transcriptome analyses of photosynthesis in three mulberry cultivars within two propagation methods (cutting and grafting) under waterlogging stress. Plants 12, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12112066 (2023).

Hou, Z. et al. Comparative proteomics of mulberry leaves at different developmental stages identify novel proteins function related to photosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 12, 797631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.797631 (2021).

Dai, F. W., Wang, Z. J., Luo, G. Q. & Tang, C. M. Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses of autotetraploid and diploid mulberry (Morus alba L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 22938–22956 (2015).

Kruthika, H. S., Rukmangada, M. S. & Naik, V. G. Genome size, chromosome number variation and its correlation with stomatal characters for assessment of ploidy levels in a core subset of mulberry (Morus spp.) germplasm. Gene 25, 147637 (2023).

Leitch, A. R. & Leitch, I. J. Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science 320, 481–483. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153585 (2008).

Udall, J. A. & Wendel, J. F. Polyploidy and crop improvement. Crop Ence 46, S3–S14. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2006.07.0489tpg (2006).

SolÌs Neffa, V. G. & Fernndez, A. Chromosome studies in Turnera (Turneraceae). Genet. Mol. Biol. 23, 925–930. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-47572000000400037 (2000).

Vamosijana, C. & Mcewenjamie, R. Origin, elevation, and evolutionary success of hybrids and polyploids. Botany-Botanique 91, 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjb-2012-0177 (2012).

Kushwah, K. S., Patel, S., Chaurasiya, U. & Wani, M. B. The effect of Colchicine on Vicia faba and Chrysanthemum carinatum (L.) plants and their cytogenetical study. Vegetos 34(2), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-021-00204-2 (2021).

Lin, H. et al. Production of polyploids from cultured shoot tips of Eucalyptus globulus Labill by treatment with colchicine. Afr. J Biotechnol. 9, 2252. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091674 (2010).

Zhang, C. et al. Comparative analysis of active components and transcriptome between autotetraploid and diploid of Dendrobium huoshanense. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 45, 5669–5676 (2020).

Zhang, X., Deng, M. & Fan, G. Differential transcriptome analysis between Paulownia fortune and its synthesized autopolyploid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 5079–5093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15035079 (2014).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Fan, X. M., Yuan, D. Y. & Tang, J. Sporogenesis and gametogenesis in Chinese chinquapin (Castanea henryi (Skam) Rehder & Wilson) and their systematic implications. Trees 29, 1713–1723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-015-1251-y (2015).

Li, Y. Q. et al. Effects of decomposing leaf litter of Eucalyptus grandis on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Lolium perenne. J. Agric. Sci. 5, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v5n3p123 (2013).

Zhang, Y. J., Yang, Q. Y., Le, D. W., Goldstein, G. & Cao, K. F. Extended leaf senescence promotes carbon gain and nutrient resorption, importance of maintaining winter photosynthesis in subtropical forests. Oecologia 173, 721–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-013-2672-1 (2013).

Terashima, I. & Hikosaka, K. Comparative ecophysiology of leaf and canopy photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 18, 1111–1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00623.x (1995).

Vogelmann, T. C., Nishio, J. N. & Smith, W. K. Leaves and light captureLight propagation and gradients of carbon fixation within leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 1, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(96)80031-8 (1996).

Sugiyama, S. Polyploidy and cellular mechanisms changing leaf size: comparison of diploid and autotetraploid populations in two species of Lolium. Ann. Bot. 96(5), 931–938 (2005).

Procko, C. et al. Leaf cell-specific and single-cell transcriptional profiling reveals a role for the palisade layer in UV light protection. Plant Cell 34(9), 3261–3279. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koac167 (2022).

Jamie, M. & Howard, G. Stomatal biology of CAM plants. Plant Physiol. 174, 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00114 (2017).

Lawson, T. & Blatt, M. R. Stomatal size, speed, and responsiveness impact on photosynthesis and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol. 164(4), 1556–1570. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.237107 (2014).

Santos, M. G. et al. Stomatal responses to light, CO2, and mesophyll tissue in Vicia faba and Kalanchoë fedtschenkoi. Front Plant Sci. 12, 740534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.740534 (2021).

Zhang, N. et al. Biochemical versus stomatal acclimation of dynamic photosynthetic gas exchange to elevated CO2 in three horticultural species with contrasting stomatal morphology. Plant Cell Environ. 47(12), 4516–4529. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091674 (2024).

Resende, M. D. et al. Genomic selection for growth and wood quality in Eucalyptus, capturing the missing heritability and accelerating breeding for complex traits in forest trees. New Phytol. 194, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04038.x (2012).

Chen, L., Guo, H., Chen, S., Yang, H. & Shahid, M. Q. Comparative study on cytogenetics and transcriptome between diploid and autotetraploid rice hybrids harboring double neutral genes. PLoS ONE 15, e0239377. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239377 (2020).

Cheng, W. et al. Transcriptome-based gene expression profiling of diploid radish (raphanus sativus) and the corresponding autotetraploid. Mol. Biol. Rep. 46, 933–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-018-4549-1 (2019).

Coate, J. E., Bar, H. & Doyle, J. J. Extensive translational regulation of gene expression in an allopolyploid (glycine dolichocarpa). Plant Cell 26, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.119966 (2014).

Casneuf, T., Bodt, S. D., Raes, J. & Steven, M. Nonrandom divergence of gene expression following gene and genome duplications in the flowering plant arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 7, R13. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-r13 (2006).

Song, C. et al. In-depth analysis of genomes and functional genomics of orchid using cutting-edge high-throughput sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1018029. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1018029 (2022).

Masclaux-Daubresse, C., Reisdorf-Cren, M. & Orsel, M. Leaf nitrogen remobilisation for plant development and grain filling. Plant Biol. 10, 23–36 (2008).

Smith, A. M. & Stitt, M. Coordination of carbon supply and plant growth. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1126–1149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01708.x (2007).

Portis, A. R. & Parry, M. A. J. Discoveries in Rubisco (Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase): A historical perspective. Photosynth. Res. 94(1), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-007-9225-6 (2007).

Harrison, E. P., Olcer, H., Llcyd, J. C., Patricka, L. S. & Christine, R. Small decreases in SBPase cause a linear decline in the apparent RuBP regeneration rate, but do not affect Rubisco carboxylation capacity. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1779–1784. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1779 (2001).

Raines, C. A., Harrison, E. P., Hülya, Ö. & Julie, C. Lloyd Investigating the role of the thiol-regulated enzyme sedoheptulose-1, 7-bisphosphatase in the control of photosynthesis. Physiol. Plant. 110, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2000.1100303.x (2000).

Tamoi, M., Nagaoka, M., Miyagawa, Y. & Shigeru, S. Contribution of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase to the photosynthetic rate and carbon flow in the Calvin cycle in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcj004 (2006).

Jiang, Y. H., Wang, D. Y. & Wen, J. F. The independent prokaryotic origins of eukaryotic fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-1, 7-bisphosphatase and the implications of their origins for the evolution of eukaryotic Calvin cycle. BMC Evol. Biol. 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-208 (2012).

Gutle, D. D. et al. Chloroplast FBPase and SBPase are thioredoxin-linked enzymes with similar architecture but different evolutionary histories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 113, 6779–6784. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606241113 (2016).

Rojas-gonzalez, J. A. et al. Disruption of both chloroplastic and cytosolic FBPase genes results in a dwarf phenotype and important starch and metabolite changes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2673–2689. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv062 (2015).

Chen, J. H. et al. Regulation of Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes under high temperature stress. aBIOTECH 3(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42994-022-00068-3 (2022).

Miyagawa, Y., Tamoi, M. & Shigeoka, S. Overexpression of a cyanobacterial fructose-1,6-/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase in tobacco enhances photosynthesis and growth. Nat. Biotech. 19, 965–969. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1001-965 (2001).

Zhao, H., Tang, Q., Chang, T., Xiao, Y. & Zhu, X. G. Why an increase in activity of an enzyme in the Calvin–Benson cycle does not always lead to an increased photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate?—a theoretical analysis. In Silico Plants https://doi.org/10.1093/insilicoplants/diaa009 (2020).

Gates, D. M. Mathematical models in plant physiology. A quantitative approach to problems in plant and crop physiology. J. H. M. Thornley. Q. Rev. Biol. 52(1), 97–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/409778 (1977).

Xuan, Y., Ma, B., Dong Li, Y., Tian, Q. Z. & He, N. Chromosome restructuring and number change during the evolution of Morus notabilis and Morus alba. Horticulture Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhab030 (2022).

Yan, F. et al. Metabolomics reveals 5-aminolevulinic acid improved the ability of tea leaves (Camellia sinensis L.) against cold stress. Metabolites 12(5), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12050392 (2022).

Liu, D., Meng, S., Xiang, Z. H., He, N. J. & Yang, G. W. Antimicrobial mechanism of reaction products of Morus notabilis (mulberry) polyphenol oxidases and chlorogenic acid. Phytochemistry 163, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.03.026 (2019).

Beddo, V. C. & Kreuter, F. A handbook of statistical analyses using SPSS. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v011.b02 (2004).

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangxi Key R&D Program Project (Guike AB23026066); China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Q.L., C.Q., D.L., Performed the experiments: D.L., S.H., R.M., Y.Z., X.L., Analyzed the data and prepared figures: D.L., G.Z., C.Z., Wrote the paper: D.L., S.H., R.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Lin, Q., Huang, S. et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals different photosynthetic characteristics of mulberry trees with different ploidy levels. Sci Rep 15, 15892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99598-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99598-1