Abstract

In a loose-string task an out-of-reach tray baited with food can only be retrieved by simultaneously pulling on both ends of a string threaded through the loops on the tray. This task is used to assess an animal’s ability to cooperate, with each animal only having access to one end of the string. Some studies use the loose-string task in a pre-training phase, during which animals are individually taught to pull both ends of the string. Usually, no additional tests are conducted to determine whether the animals have understood how the loose string works. It is conceivable that a lack of knowledge of the causal basis of the loose-string task could make it more challenging to grasp how the partner can assist with it. Here, we tested whether Hooded crows could acquire some knowledge of the causal basis of the loose-string task. Prior to the critical test (Phase 3), the birds were presented with two different tasks (Phase 1 and Phase 2) to allow them to acquire some knowledge of the causal basis of the task. The results may indicate that, as a consequence of the experience gained, some crows may have begun to understand how the loose string works.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the domain of physical cognition, one of the most widely used paradigms is the string-pulling task (e.g.1,2,3,4,5,6), in which the animal must pull the baited string in order to obtain the bait. Even when using a series of such tasks of varying complexity, it is challenging to distinguish between solutions produced by reinforcement of random behaviour (i.e. induced by associative learning) and those resulting from understanding or reasoning3,7. Bluff and colleagues8 were correct to point out that it is challenging to distinguish between associatively learned behaviour and associatively learned knowledge.

A variation of a string-pulling task can be considered the loose-string task, in which an out-of-reach tray baited with food rewards can be retrieved only by simultaneously pulling on both ends of a string threaded through the loops on the tray. The task, in which each of the two animals only has access to one end of the string, is commonly used for studies on animal cooperation. Some studies use the loose-string task in a pre-training phase, during which animals are individually taught to pull both ends of the string simultaneously9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Usually, no additional tests are conducted to determine whether the animals have understood how the loose string works. We found a single study that conducted a transfer test at the end of the training phase to assess whether the animals could generalise from the training trials to complete a task that presented the string in a novel manner13.

Understanding of the causal basis of the loose-string task has rarely but been mentioned (e.g.11,18) when discussing factors influencing the outcome of a cooperative task. Although there is another point of view that the ability of the animals to learn the role of their partners neither implies nor requires that they understood how the loose string and the apparatus itself worked (e.g.19).

It is conceivable that a lack of knowledge of the causal basis of the loose-string task could make it more challenging to understand how the partner can assist with it. In the current study, we investigated whether Hooded crows (Corvus cornix) could acquire some knowledge of the causal basis of the loose-string task.

Crows possess advanced cognitive abilities. They can extract relations among items and between relations, form abstract categories not tied to specific perceptual features and use abstract representations20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

The advanced cognitive abilities of corvids are determined by the high level of their brain complexity32,33,34. They are characterised by an expanded associative meso- and nidopallium35,36. Meso- and nidopallium of corvids (at least in Carrion crows) is more densely and diversely innervated by dopaminergic fibres and they have more expended nidopallium caudolaterale (the functional analogue to the mammalian prefrontal cortex) compared to pigeons and chickens37.

Hooded crows are not specialised tool users, but like other members of the corvid family38,39, they drop shells on rocks or nuts on motorways, which could be considered an example of proto-tool use. They throw twigs at intruders during the nesting season, although this may be a manifestation of displacement behaviour, which is typical for them when they are frustrated40.

As previously demonstrated by Bagotskaya et al. (2012), some Hooded crows are capable of solving sophisticated variants of horizontal string-pulling tasks for which the proximity rule is not applicable. However, it remains unclear whether crows understand the principles underlying a string-pulling task or whether this result is due to rapid associative learning by using perceptual-motor feedback2,3.

We have recently found41 that Hooded crows similar to tool-specialised New Caledonian crows42 and non-tool-specialised Goffin’s cockatoos43, can manufacture objects according to a mental template.

In the present study, a set of three tasks was applied, comprising one standard task (Phase 2) and two novel ones (Phase 1 and Phase 3). Prior to the critical test (Phase 3), the birds were presented with two different loose-string tasks (Phase 1 and Phase 2) to allow them to acquire some knowledge of the causal basis of the task. In the initial two phases, the ability of the crows to cope with the task spontaneously was assessed, and subsequently, the birds were trained to solve it if they failed. The third task was designed to assess whether the experience gained during the previous two tasks had resulted in the acquisition of some knowledge about the causal basis of the loose-string task.

Methods

Subjects

Six adult Hooded crows (Corvus cornix) were tested. All of them were rescued from the wild due to injuries and were housed in the outdoor group aviary (500 × 250 × 300 cm) on the territory of the Lomonosov Moscow State University Botanical Garden. The aviaries are equipped with perches (tree branches, wooden ladders, stumps), wooden shelters, toys, metal and ceramic feeders and plastic basins with water. The birds are kept on an ad libitum diet (rat and mouse carcasses, steamed crops and seeds with added vegetable oil and vitamins, eggs, seasonal fruits and vegetables, and fresh water). If the crows refused to participate in the experiment, then they received food without animal protein for 1 or 2 days.

Glaz and Schnobel were kept for over 15 years, and Rodya, Joe, Grisha, and Clara for over four. The sex of the birds is not known. Based on sex-size dimorphism and behaviour, it can be assumed that Grisha and Clara are females, and other crows are males. Prior to this experiment, all birds, except Grisha, had participated in experiments based on Aesop’s fable paradigm. Two of the subjects (Glaz and Schnobel) had previously participated in a series of highly varied identity matching-to-sample tasks and later spontaneously performed relational matching-to-sample tasks26. Glaz and Schnobel participated in a string-pulling experiment44. None of the other subjects had any prior experience with strings.

The experiments were conducted from 2021 to 2023. All experiments were appetitive, non-invasive and based exclusively on behavioural tests. They were conducted in full compliance with the bioethical requirements of Directive 2010/63/EU and Federal Law of 27.12.2018 N498-FZ (ed. of 27.12.2019) 'On Responsible Treatment of Animals and Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation’. Research was carried out with approval from the MSU bioethics committee (reference number № 157-d). The study was also carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Therefore, the study was conducted in accordance with all the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental setup

For the study, birds were transferred to an experimental room (250 × 400 cm). Subjects were placed in a wire mesh cage (65 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm) with a wooden perch and a bowl of water. At the bottom of the front wall, there was a slit (50 cm × 9 cm) through which a wooden platform (35 cm × 20 cm) could be inserted into the cage (Fig. 1).

A ceramic tray (10 cm × 10 cm) with a transparent plastic cup (3 cm high and 4 cm in diameter) glued to it for the bait (2 mealworm larvae) was placed between two wooden rails (20 cm × 1 cm) attached to the platform, to guide tray movement. Two metal loops were glued to the front edge of the ceramic tray 8 cm apart, through which a string was threaded. Specific characteristics of the strings are outlined in the descriptions of the particular experiments. The vast majority of the strings were striped, with alternating dark and light areas, in order to enhance the visibility of their movement within the loops.

The platform with the tray was prepared out of the bird’s sight (this was done below the level of the table on which the bird cage was situated). Prior to each trial, the platform was initially placed in front of the bird for 2 to 3 s, allowing the crow to see the string, but preventing the bird from reaching it. Then, the platform was partially slid into the cage, so the crow could reach the ends of the string. If the bird did not pull an end of a string within 2 min, the platform was removed from the cage. The intertrial interval was approximately 1 min, which was the estimated time required to prepare the platform with the tray for the next trial. The number of trials per day varied considerably, depending on the bird’s willingness to work.

To eliminate the possibility of a ‘Clever Hans’ error, an opaque plastic screen (60 cm × 45 cm) was placed between the experimenter and the crow, preventing visual contact between them. As the experimenter was unable to see the bird, they had to rely on the movement of the ceramic tray or the string to judge the outcome of each trial. The bird’s choice was correct if the tray moved and incorrect if the string slipped.

Familiarisation and pre-training

The crows were first habituated to being in the experimental cage and receiving a reward from the experimenter via the slit in the front wall. The birds were then provided with the opportunity to pull the baited tray in using a string (red with black stripes, 35 cm in length and 0.3 cm in diameter) that had been threaded through loops on the tray and then tied to the middle of the other end of the same string, which was placed on the platform between the slats (Fig. 2a). The pre-training phase was concluded when each bird had pulled the tray 10 times.

Diagram of the platforms with the tray and the strings with stoppers: (a) Pre-training, (b) Phase 1: the loose-string task with stopper, (c) Phase 2: the standard loose-string task, (d) Phase 3: the loose-string task with an additional short string, (e) 30 strings with unique stoppers for the test sessions, (f) one string with a knot used in the first training stage, (g) three strings with additional new stoppers used in the second training stage.

Phase 1: the loose-string task with stoppers

In Phase 1, we initially tested whether the birds could solve the task spontaneously. If they failed, we taught them to pull a tray in by a specific end of a loose string—the one to which no stopper was attached.

The string (60 cm in length and 0.3 cm in diameter) was threaded through two loops on the tray, with both ends (25 cm in length) placed parallel between the slats. At one end of the string, 12 or 18 cm from it, an object (beads, buttons, etc.) was tied. The size of the object (the stopper) was larger than the diameter of the loop on the tray, so it kept the string from slipping out of the loop, but only if the bird pulled the end of the string without the stopper (Fig. 2b). The ends of the string with the stopper were placed on the different sides in a semi-random manner. The tray could also be retrieved by simultaneously pulling both ends of the string.

For the analysis, only the initial choice was considered. The trial was considered successful if the bird initially selected the ‘correct’ end. If the bird initially selected the ‘incorrect’ end, the platform with the tray was removed from the bird’s reach, and the trial was considered unsuccessful (Supplementary Video).

In the first test session we tested whether the birds could spontaneously solve this task over the course of 30 trials. We used three types of strings (blue with dark blue stripes, red with black stripes, or pink with purple stripes), which were alternated in a semi-random manner, and 30 unique stoppers in each of the 30 trials (Fig. 2e).

If crows failed to complete the task, they were trained to pull the tray in (first training stage). A knot was used as a stopper, tied at a distance of 12 cm from the end of the string (Fig. 2f). The birds were trained through trial-and-error until they were able to successfully retract the tray in 9 out of 10 consecutive trials (p = 0.022, two-tailed binomial test).

To determine whether any generalisation of learning had occurred, subjects were given a second test session with 30 different stoppers (30 trials).

In the event of a failure, the crow was trained (second training stage) with three new stoppers (Fig. 2g) that were not among the 30 used previously. Training was conducted until the crows were able to successfully retrieve the tray in 20 out of 24 consecutive trials (p = 0.002, two-tailed binomial test).

Thereafter, the subjects were presented with the third test session with 30 different stoppers.

Phase 2: the standard loose-string task

In Phase 2, we tested whether crows acquired an understanding of how a loose string works or if they just learned a simple associative rule (i.e., 'pull the end without the stopper’) while completing the previous task.

The standard loose-string task was used (Fig. 2c). A light blue string with dark blue stripes (35 cm in length, with a diameter of 0.3 cm) was threaded through the loops on the tray. The tray could be retrieved only by simultaneously pulling on both ends of a string (Supplementary Video).

We first tested whether the birds could complete the task spontaneously. If they could not, they were trained to pull the tray in by gradually shaping this behaviour. During training, the ends of the string were initially overlapped. Once the subject had pulled the tray in 9 times in a row, the distance between the strings was increased by 1 cm. The training was completed when the birds were able to pull the tray in by the two ends, with a distance of 5 cm between them.

A further 30 trials were conducted to ascertain whether the birds had developed a motor pattern of selecting the left or right end first.

Phase 3: the loose-string task with an additional short string

In Phase 3, we tested whether the experience gained during the preceding two tasks had led to an understanding of the principles underlying a loose-string task. In particular, we determined whether crows would select the ends of a string passed through loops in a tray if an additional short string not connected to the tray was placed parallel to them.

In addition to a long light blue string with dark blue stripes (35 cm in length, with a diameter of 0.3 cm) threaded through loops on the tray, a short string (same colour and diameter, 11 cm in length) was placed on the platform (Fig. 2d). The short string was placed in a semi-random manner on the sides or between the ends of the long string (parallel to them). The end of the short string was not attached to the ceramic tray and was positioned at a distance of 3 cm from its edge. Two test sessions, consisting of 30 trials each, were conducted.

Video coding and analyses

All training and test trials were recorded using a video camera. Trials were filmed and coded in terms of subjects’ binary choices. Additionally, data was recorded manually at the time of training and testing. All trials in Phase 3 were also coded according to the order in which the subject combined the strings.

Data analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.0.3). Since only six subjects were tested, only within-subject data was statistically analysed. Individual performance within each condition was assessed using binomial tests.

Specifically, the 'binom.test()' function in R was used to determine if the observed success rates were significantly different from what would be expected by chance. The number of correct responses out of the total number of trials was tested against a chance level of 50% (Phase 1), 33% (Phase 3; the tray could be pulled in by the two ends using two out of the six possible combinations of ends), or 66% (Phase 3; two out of three ends were connected to the tray).

The success rates, along with the presence of the motor pattern of selecting the left or right end first in Phase 2, were analysed using a two-tailed binomial test.

For comparing the performance of crows in two different sessions in Phase 3, we applied the two-tailed paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The 'wilcox.test()' function in R was used to calculate the test statistics and p-values, providing insights into the learning effect. This non-parametric test is appropriate for evaluating differences between two related samples and does not assume a normal distribution of the data.

In Phase 3, to compare success rates and the frequency of use of a particular strategy between different types of trials, we used a two-tailed z-test based on the proportions of successes or frequencies. This method was particularly useful for cases with unequal trial numbers. The z-test was conducted by calculating the pooled proportion of successes and using this to determine the standard error. The z-score was computed using the formula: z = (p1 − p2)/SE, where p1 and p2 are the proportions of successes in each condition, and SE is the standard error of the difference between the two proportions. The significance of the z-score was evaluated to determine if the differences in success rates or frequencies were statistically significant.

Graphs were built in GraphPad Prism.

Results

Familiarisation and pre-training

All birds retrieved the tray in each of the first 10 trials.

Phase 1: the loose-string task with stoppers

In the first test session, none of the six crows chose the ‘correct’ end (the one without a stopper) above chance. Glaz correctly selected the end in 19 of the 30 trials (p = 0.201, two-tailed binomial test), Rodya in 11 (p = 0.201), Joe in 16 (p = 0.856), Clara and Schnobel in 17 trials (p = 0.585). Grisha chose the ‘incorrect’ end above chance (21/30, p = 0.043).

Subsequently, the crows were trained to pull the tray in using the end of the string to which the stopper was not attached (first training stage). Initially, a knot was used as a stopper. Crows reached the criterion (retrieve the tray in 9 out of 10 consecutive trials) after 80 (Glaz), 309 (Grisha), 38 (Rodya), 70 (Joe), 18 (Clara), and 95 (Schnobel) trials.

In the second test session three crows chose the ‘incorrect’ end above chance. Schnobel pulled the ‘correct’ end in 25 out of 30 trials (p = 0.0003, two-tailed binomial test), Glaz in 21 (p = 0.043), and Grisha in 20 (p = 0.099). Initially, a less stringent one-tailed test was used to assess the reliability of the results, according to which Grisha’s results were significant (p = 0.049). Therefore, this bird proceeded to the next stage without additional training.

The remaining three subjects were trained with three new stoppers (second training stage). Clara died. Rodya and Joe reached the criterion (retrieve the tray in 20 out of 24 consecutive trials) after 420 and 453 trials.

In the third test session Joe selected the ‘correct’ end above chance (23/30, p = 0.005, two-tailed binomial test) and Rodya performed at chance (19/30, p = 0.201). However, he selected the ‘correct’ string above chance in the fourth test session, which was conducted immediately after the third (28/30, p < < 0.0001).

In Phase 1 none of the crows ever attempted to bring the two ends together, i.e. to retrieve the tray in the second possible way (as in the standard loose-string task).

Phase 2: the standard loose-string task

In the initial 30 trials, none of the crows pulled the tray in. They did not attempt to bring the two ends together.

Further training was conducted. Four crows reached the criterion (retrieve the tray in 9 out of 10 consecutive trials) after 150 (Glaz), 105 (Grisha), 152 (Rodya), and 243 (Joe) trials. Schnoebel failed to reach the criterion in 200 trials and subsequently died.

The additional 30 trials conducted after the birds reached the criterion revealed that Grisha and Rodya displayed a distinct motor pattern of taking a specific (left or right) end first. In all 30 trials, Grisha took the left end of first, and Rodya took the right end first. The other two birds did not exhibit a distinct motor pattern: Glaz took the right or left end first in 16 and 14 trials, respectively (p = 0.856, two-tailed binomial test), while Joe took the right or left end first in 19 and 11 trials (p = 0.201).

Phase 3: the loose-string task with an additional short string

The results for each crow in each of the 60 trials are presented in the Supplementary Table S1.

In some trials, all four crows demonstrated an unexpected solution to the problem, pulling all three ends (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Video). Glaz used this strategy in 20% of trials, Grisha in 38.3%, and Rodya and Joe both in 43.3% of trials.

Phase 3: (a) number of trials where crows pulled all three ends in different trial types (the data are presented for all 60 trials), (b) number of trials in the first and second 30-trial sessions where the crows pulled all three ends; Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (paired, two-tailed) results were used to compare the number of trials where crows pulled all three ends in the first and second sessions.

Grisha was significantly less likely to use this strategy in trials where the short string was in the middle compared to both trials where the short string was on the left (p = 0.006, two-tailed z-test) and on the right (p = 0.002). Rodya was less likely to use this strategy in trials where the short string was on the left, compared to trials where the short string was in the middle (p = 0.025). With regard to the remaining birds, no clear effect of trial type on this behaviour was observed.

Glaz and Joe used this strategy about equally often in both sessions (p = 0.072 and p = 0.346, paired two-tailed Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test), and Rodya and Grisha did it more often in the first session (p = 0.006 and p = 0.002, Fig. 3b).

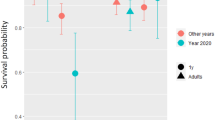

In those trials where crows combined the two ends, only Rodya selected the ‘correct’ ends significantly above chance across both sessions (Table 1, Fig. 4), as well as in each of the two sessions.

A comparison of the performance of the all crows in the first and second sessions revealed no significant effect of experimental learning on the performance of any of them (two-tailed z-test, Table 1).

The type of trial had a significant impact on the success of the task for all four crows (Fig. 5). During the trials in which a short string was in the middle, none of the crows selected the ‘correct’ ends of the long string above chance. Glaz did not pull the tray in any of the 15 trials. The performance of other birds was significantly worse in this type of trial compared to the other two types.

Phase 3: crow’s performance in trials in which birds pulled the two ends, for each of the three trial types, in the number of correct choices from the number of trials. Individual performance was assessed using a two-tailed binomial test with chance level at 33% (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). Z-test (two-tailed) was used to compare the success rates in first and second sessions (# p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001).

In some trials, all four crows combined the left and right ends (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Video). Glaz only did this once in the first trial, connecting the ‘correct’ end of the long string with the ‘incorrect’ end of the short string. Grisha connected the left and right ends in two trials, combining the ‘correct’ ends. Rodya did the same in five trials. Joe connected the left and right ends in seven trials, combining the ‘correct’ ends in three of them.

Glaz and Rodya selected the ‘correct’ ends above chance when the short string was on the right, but not when it was on the left (Fig. 5). The z-test confirmed that Glaz’s accuracy rates differed significantly between the two types of trials—when the short string was on the right or on the left side (p = 0.041, two-tailed). Joe chose the ‘correct’ ends above chance only when the short string was on the left, but the z-test showed no difference in accuracy rates between the two types of trials.

To assess the potential influence of a motor pattern on task performance, we analysed the number of trials in which birds took strings in the left-to-right direction and vice versa (Fig. 6). Grisha and Rodya displayed the same motor pattern in the Phase 3 as in the end of Phase 2. Grisha took ends from left to right in 56 out of 60 trials and Rodya took ends from right to left in 59 out of 60 trials.

Rodya selected one of the ‘correct’ ends first above chance in the second session (26/30, p = 0.02, two-tailed binomial test with chance level at 66%, Supplementary Table S1), but not in the first (21/30, p = 0.847). The z-test indicated no significant difference in accuracy rates between the two sessions (p = 0.116, two-tailed z-test).

Since only Rodya succeeded in this test (Table 1, Fig. 4), a more detailed analysis of his behaviour across the three trial types was conducted to identify the factors that influenced the decision-making process (Table 2).

The analysis further confirmed that Rodya’s behaviour was strongly influenced by the motor pattern. In only one out of 60 trials did he take the left end first (the ‘correct’ end). He took the right end first in 41 trials, and the middle end first in 18 trials. He took the nearest left end second in 55 out of 60 trials. In trials in which Rodya took the middle end first, he always took the left end second.

Despite the presence of a strong motor pattern, in trials where the ‘incorrect’ short string was on the right side, Rodya more often (p = 0.003, two-tailed z-test) took the ‘correct’ middle end first (9/11) when pulling the two ends.

Rodya pulled all three ends more often (20 out of 26 trials, p = 0.0001, two-tailed z-test) in trials where one of the first two taken ends was the wrong one (Supplementary Table S1). Among the other crows, only Joe, similarly to Rodya, pulled all three ends more often in trials where one of the ends taken first was the wrong one (22 out of 26 trials, p < < 0.0001, two-tailed z-test).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to test whether Hooded crows could understand how a loose string works. Prior to the critical test (Phase 3), the birds were presented with two different loose-string tasks (Phase 1 and Phase 2) to allow them to acquire some knowledge of the causal basis of the task.

All three tasks were characterised by visible causality. The loops on the tray through which the string was passed were within sight of the birds. The strings had dark and light stripes, which may have facilitated tracking the movement of the string in the loops.

The simple associative rules that the birds learnt while being trained to solve one task did not apply to the next one. On the other hand, understanding the principle of the loose string in one task would allow for the solution of the subsequent task.

This study demonstrates that all variants of the loose-string task, despite their apparent visible causality, proved challenging for the crows. None of the birds were able to spontaneously solve either the task with 30 different stoppers used in Phase 1 or the standard loose-string task in Phase 2. In Phase 1, despite the positive perceptual-motor feedback from selecting the end of the string without a stopper, the 30 trials were insufficient for short-term learning. Despite hundreds of trials in Phase 1, none of the crows found another way to solve the problem—they never attempted to bring the two ends together, i.e. to retrieve the tray in the second possible way (as in the standard loose-string task).

In Phase 1, two crows formed a sufficiently generalised rule while they were trained with a knot as a stopper, which allowed them to solve the task with 30 stoppers in the second test session. The other birds were unable to generalise their learning to new strings with a new stopper. These birds required more than 400 trials to learn to solve the same task with three new stoppers and a more rigorous learning criterion. One of these crows (Joe) completed the test with 30 new stoppers in the third test session, and the second bird (Rodya) completed it in the fourth test session, without any additional training in between.

One of the crows learnt to solve the task with the knot as a stopper in 18 trials, whereas the other required 309 trials. Some of the crows were able to complete the test session with 30 stoppers after training with a knot, while others had to learn how to solve the task with three different stoppers, which took them more than 400 trials. The results again revealed significant individual differences in learning ability between individuals, a finding that has been repeatedly noted in other studies of physical cognition (e.g. 44,45,46,47.).

The findings of Phase 2 demonstrated that the birds had only previously acquired an associative rule to pull the end without the stopper, which was not applicable to solving the novel variant of the task. The birds required between 105 and 243 trials to learn to pull the tray in by two ends. A comparable number of trials was required for parrots and rooks to learn to solve the same task11,12,17, whereas chimpanzees required only 5–10 trials10.

Two crows (Grisha and Rodya) exhibited a strong motor pattern of taking a particular end of the string first. A similar preference, known as side bias, is not uncommon in string pulling tasks and can affect performance of animals (e.g. 2,4,44,48.).

In Phase 3, we tested whether the experience gained during the previous two tasks had resulted in the acquisition of some knowledge about the causal basis of the loose-string task. If the crows had acquired an understanding of how the loose string works, then they should be able to spontaneously solve the new task, in which a short string not connected to the tray was placed parallel to the ends of a long string passed through loops in a tray.

In some trials (20%–43% of all trials), all four crows demonstrated an unexpected solution to the problem: they pulled all three ends. This strategy was an effective approach because it did not require the selection of specific ends. However, in 60 trials, this strategy did not become the dominant approach in any of the birds. Indeed, two crows (Grisha and Rodya) used this strategy more often in the first session (Fig. 3b).

If the crows initially did not connect the two ‘correct’ ends, there was a greater probability that they would also take the third end. This suggests that the crows can rely on perceptual-motor feedback, which may be either visual (the other end of a long string moves when the crow pulls the first end, motivating the bird to take it) or proprioceptive (the tension of the string that occurs when the crow picks up the two ‘correct’ ends). The importance of perceptual-motor feedback has been demonstrated in many studies, using a coiled string (e.g. 1,2,3,6,45,47,49,50.), visually restricted conditions51,52, and weight-conditioned tasks53.

Taylor and colleagues2 proposed that a 'perceptual-motor feedback loop’ and associative learning could underlie the successful solution of string pulling tasks. They also hypothesised that species with larger associative areas would integrate information between perceptual and motor pathways quicker than species with smaller associative brain areas. It was later shown that in animals with advanced cognitive abilities and high levels of brain complexity, a more complex interplay of cognitive factors may underlie the ability to solve string-pulling tasks6. It can be hypothesised that if the associative areas of the brain have developed sufficiently, perceptual feedback can initiate more complex cognitive processes, providing some knowledge of the causal basis of the experimental task45,54 or, at least, for anticipating the consequences of their own actions, that is compatible with the ‘embodied cognition’ hypothesis55,56. In humans, it has been demonstrated that the beneficial effects of feedback stem from allowing people to adjust their strategies for performing the task and not from direct reinforcement mechanisms57.

An examination of video recordings of crow’s behaviour detected the use of proprioceptive feedback in three crows (Joe, Glaz and Grisha), which could combine two ends, pull them slightly and then pick up the third end (Supplementary Video). This differs from Rodya’s behaviour, in whom we did not observe explicit use of proprioceptive feedback. In all trials, Rodya first brought the ends together without tensioning them and then abruptly pulled them, so that no ends moved prior to his actions and no tension arose (Supplementary Video).

The success of problem solving in trials where crows combined two ends depended on the position of the short string. The performance of three birds (Glaz, Grisha and Joe) was significantly worse in trials where the short string was placed in the middle (Fig. 5). It seems probable that in Phase 2, the birds may have formed a motor pattern of combining the neighbouring ends.

Two crows (Glaz and Rodya) demonstrated a preference for the ‘correct’ ends when the short string was positioned to the right but not when it was on the left. One bird (Joe) demonstrated an inverse result (Fig. 5). The poor performance demonstrated by Rodya in trials in which the short string was positioned on the left did not fit his motor pattern of taking strings in the right-to-left direction (Fig. 6, Table 2), according to which one would expect better performance in this type of the trials.

In the trials where crows combined two ends, only one crow (Rodya) selected the ‘correct’ ends above chance (Table 1, Fig. 4). A comparison of his performance in the first and second sessions revealed no notable effect of learning on the test results. The evidence that learning took place was only indicated by Rodya’s selection of one of the ‘correct’ ends at a rate above chance in the second session, contrasting with his performance in the first session. The fact that Rodya avoided selecting the end of the string that was not connected to the tray is consistent with our previous results, which indicated that some crows successfully solved the task with two baited strings, one of which was broken44.

As mentioned above, the analysis of Rodya’s behaviour in Phase 3 did not reveal a clear reliance on perceptual-motor feedback. Nevertheless, Rodya’s reliance on the perceptual-motor feedback may have been subtle and unobvious when assessed through the recordings. In any case, the proprioceptive feedback did not serve as the sole determining factor, at least in the case of Rodya. To illustrate, in six out of the 26 trials in which he pulled all three ends, he initially combined two ‘correct’ ends and could perceive the string tension, yet still took the third ‘incorrect’ end. In the loose-string task perceptual feedback could only affect the choice of the second or third ends, but not the first one. Despite the strong influence of the motor pattern, with Rodya taking the left end first in only one out of 60 trials, he selected one of the ‘correct’ ends first above chance in the second session.

Rodya’s successful completion of the loose-string task with the additional short string in Phase 3 during the first session (i.e., within the first 30 trials) suggests that the experience gained in Phase 1 and Phase 2 enabled him to develop an understanding of the causal basis of the task. The hypothesis that Rodya began to understand how a loose string works is supported by the observation that in the five trials, in which he connected the left and right ends, he did so exclusively with the ‘correct’ ends.

Therefore, it can be posited that some crows may have acquired some knowledge of the causal basis of the loose-string task. Although only one out of the four crows may have begun to understand how loose stringing works, this could indicate that this ability is present in this species of birds.

This study represents the first attempt to develop a set of tasks to assess the animals’ ability to understand how the loose string works. The set of tasks can be further developed and improved. It may be beneficial to use coiled strings, which could help clarify the influence of perceptual feedback. Further studies are necessary to clarify the mechanisms underlying the solution of the loose-string tasks in animals of different species.

The application of the set of string-pulling tasks provides animals with extensive experience with the paradigm, which may in turn lead to their understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying loose-string tasks. Cooperative tests with such animals may possibly provide a better understanding of the cognitive underpinnings of cooperative behaviour. Conversely, the cooperative tasks themselves can serve as an additional test for assessing understanding of how the loose string works.

Data availability

All supporting data is available as an electronic supplementary material.

References

Johnsson, R. D. et al. Wild Australian magpies learn to pull intact, not broken, strings to obtain food. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 77, 49 (2023).

Taylor, A. H. et al. An investigation into the cognition behind spontaneous string pulling in new Caledonian crows. PLoS ONE 5, e9345 (2010).

Taylor, A. H., Knaebe, B. & Gray, R. D. An end to insight? New Caledonian crows can spontaneously solve problems without planning their actions. Proc. R. Soc. B. 279, 4977–4981 (2012).

Wang, L., Zhang, D. & Sui, J. Investigation of cognitive mechanisms and strategy on solving multiple string-pulling problems in Azure-winged magpie (Cyanopica cyanus). Anim. Cogn. 24, 1–10 (2021).

Wasserman, E. A., Nagasaka, Y., Castro, L. & Brzykcy, S. J. Pigeons learn virtual patterned-string problems in a computerized touch screen environment. Anim. Cogn. 16, 737–753 (2013).

Bastos, A. P. M., Wood, P. M. & Taylor, A. H. Kea (Nestor notabilis) fail a loose-string connectivity task. Sci. Rep. 11, 15492 (2021).

Jacobs, I. F. & Osvath, M. The string-pulling paradigm in comparative psychology. J. Comp. Psychol. 129, 89–120 (2015).

Bluff, L. A., Weir, A. A. S., Rutz, C., Wimpenny, J. H. & Kacelnik, A. Tool-related cognition in New Caledonian crows. Comp. Cogn. Behav. Rev. 2, 1–25 (2007).

Hare, B., Melis, A. P., Woods, V., Hastings, S. & Wrangham, R. Tolerance allows bonobos to outperform chimpanzees on a cooperative task. Curr. Biol. 17, 619–623 (2007).

Hirata, S. & Fuwa, K. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) learn to act with other individuals in a cooperative task. Primates 48, 13–21 (2007).

Heaney, M., Gray, R. D. & Taylor, A. H. Keas perform similarly to chimpanzees and elephants when solving collaborative tasks. PLoS ONE 12, e0169799 (2017).

Seed, A. M., Clayton, N. S. & Emery, N. J. Cooperative problem solving in rooks (Corvus frugilegus). Proc. R. Soc. B. 275, 1421–1429 (2008).

Ostojić, L. & Clayton, N. S. Behavioural coordination of dogs in a cooperative problem-solving task with a conspecific and a human partner. Anim. Cogn. 17, 445–459 (2014).

Massen, J. J. M., Ritter, C. & Bugnyar, T. Tolerance and reward equity predict cooperation in ravens (Corvus corax). Sci. Rep. 5, 15021 (2015).

Asakawa-Haas, K., Schiestl, M., Bugnyar, T. & Massen, J. J. M. Partner choice in raven (Corvus corax) cooperation. PLoS ONE 11, e0156962 (2016).

Marshall-Pescini, S., Schwarz, J. F. L., Kostelnik, I., Virányi, Z. & Range, F. Importance of a species’ socioecology: Wolves outperform dogs in a conspecific cooperation task. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11793–11798 (2017).

Tassin de Montaigu, C., Durdevic, K., Brucks, D., Krasheninnikova, A. & Von Bayern, A. Blue‐throated macaws (Ara glaucogularis) succeed in a cooperative task without coordinating their actions. Ethology 126, 267–277 (2020).

Schwing, R., Jocteur, E., Wein, A., Noë, R. & Massen, J. J. M. Kea cooperate better with sharing affiliates. Anim. Cogn. 19, 1093–1102 (2016).

Plotnik, J. M., Lair, R., Suphachoksahakun, W. & De Waal, F. B. M. Elephants know when they need a helping trunk in a cooperative task. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5116–5121 (2011).

Balakhonov, D. & Rose, J. Crows rival monkeys in cognitive capacity. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8 (2017).

Lazareva, O. F. et al. Transitive responding in hooded crows requires linearly ordered stimuli. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 82, 1–19 (2004).

Magnotti, J. F., Katz, J. S., Wright, A. A. & Kelly, D. M. Superior abstract-concept learning by Clark’s nutcrackers (Nucifraga columbiana). Biol. Lett. 11, 20150148 (2015).

Magnotti, J. F., Wright, A. A., Leonard, K., Katz, J. S. & Kelly, D. M. Abstract-concept learning in Black-billed magpies (Pica hudsonia). Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 431–435 (2017).

Samuleeva, M. V. & Smirnova, A. A. Emergence of reflexivity relation without identity matching-to-sample training in hooded crows (Corvus cornix). Cogn. Neurosci. 65 (2020).

Smirnova, A. A., Lazareva, O. F. & Zorina, Z. A. Use of number by crows: Investigation by matching and oddity learning. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 73, 163–176 (2000).

Smirnova, A. A., Zorina, Z. A., Obozova, T. A. & Wasserman, E. A. Crows spontaneously exhibit analogical reasoning. Curr. Biol. 25, 256–260 (2015).

Smirnova, A. A., Obozova, T. A., Zorina, Z. A. & Wasserman, E. A. How do crows and parrots come to spontaneously perceive relations-between-relations?. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 37, 109–117 (2021).

Seed, A. M., Emery, N. J. & Clayton, N. S. Intelligence in corvids and apes: A case of convergent evolution?. Ethology 115, 401–420 (2009).

Wilson, B., Mackintosh, N. J. & Boakes, R. A. Transfer of relational rules in matching and oddity learning by pigeons and corvids. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 37, 313–332 (1985).

Wright, A. A., Magnotti, J. F., Katz, J. S., Leonard, K. & Kelly, D. M. Concept learning set-size functions for Clark’s nutcrackers. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 105, 76–84 (2016).

Wright, A. A. et al. Corvids outperform pigeons and primates in learning a basic concept. Psych. Sci. 28, 437–444 (2017).

Güntürkün, O. & Bugnyar, T. Cognition without Cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 291–303 (2016).

Güntürkün, O., Ströckens, F., Scarf, D. & Colombo, M. Apes, feathered apes, and pigeons: differences and similarities. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 16, 35–40 (2017).

Güntürkün, O., Von Eugen, K., Packheiser, J. & Pusch, R. Avian pallial circuits and cognition: A comparison to mammals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 71, 29–36 (2021).

Sayol, F., Lefebvre, L. & Sol, D. Relative brain size and its relation with the associative pallium in birds. Brain Behav. Evol. 87, 69–77 (2016).

Ströckens, F. et al. High associative neuron numbers could drive cognitive performance in corvid species. J. Comp. Neurol. 530, 1588–1605 (2022).

Von Eugen, K., Tabrik, S., Güntürkün, O. & Ströckens, F. A comparative analysis of the dopaminergic innervation of the executive caudal nidopallium in pigeon, chicken, zebra finch, and carrion crow. J. Comp. Neurol. 528, 2929–2955 (2020).

Shumaker, R. W., Walkup, K. R. & Beck, B. B. Animal Tool Behavior: The Use and Manufacture of Tools by Animals (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Davenport, J., O’Callaghan, M. J. A., Davenport, J. L. & Kelly, T. C. Mussel dropping by Carrion and Hooded crows: biomechanical and energetic considerations. J. Field Ornithol. 85, 196–205 (2014).

Heinrich, B. Raven tool use?. The Condor 90, 270–271 (1988).

Smirnova, A. A., Bulgakova, L. R., Cheplakova, M. A. & Jelbert, S. A. Hooded crows (Corvus cornix) manufacture objects relative to a mental template. Anim. Cogn. 27, 36 (2024).

Jelbert, S. A., Hosking, R. J., Taylor, A. H. & Gray, R. D. Mental template matching is a potential cultural transmission mechanism for New Caledonian crow tool manufacturing traditions. Sci. Rep. 8, 8956 (2018).

Laumer, I. B., Jelbert, S. A., Taylor, A. H., Rössler, T. & Auersperg, A. M. I. Object manufacture based on a memorized template: Goffin’s cockatoos attend to different model features. Anim. Cogn. 24, 457–470 (2021).

Bagotskaya, M. S., Smirnova, A. A. & Zorina, Z. A. Corvidae can understand logical structure in baited string-pulling tasks. Neurosci. Behav. Physi. 42, 36–42 (2012).

Hofmann, M. M., Cheke, L. G. & Clayton, N. S. Western scrub-jays (Aphelocoma californica) solve multiple-string problems by the spatial relation of string and reward. Anim. Cogn. 19, 1103–1114 (2016).

Riemer, S., Müller, C., Range, F. & Huber, L. Dogs (Canis familiaris) can learn to attend to connectivity in string pulling tasks. J. Comp. Psychol. 128, 31–39 (2014).

Wakonig, B., Auersperg, A. M. I. & O’Hara, M. String-pulling in the Goffin’s cockatoo (Cacatua goffiniana). Learn. Behav. 49, 124–136 (2021).

Baciadonna, L., Cornero, F. M., Clayton, N. S. & Emery, N. J. Mirror-mediated string-pulling task in Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius). Anim. Cogn. 25, 691–700 (2022).

Alem, S. et al. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002564 (2016).

Danel, S., Von Bayern, A. M. P. & Osiurak, F. Ground-hornbills (Bucorvus) show means-end understanding in a horizontal two-string discrimination task. J. Ethol. 37, 117–122 (2019).

Gaycken, J., Picken, D. J., Pike, T. W., Burman, O. H. P. & Wilkinson, A. Mechanisms underlying string-pulling behaviour in green-winged macaws. Behaviour 156, 619–631 (2019).

Chaves Molina, A. B., Cullell, T. M. & Mimó, M. C. String-pulling in African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus): Performance in discrimination task. Behaviour 156, 847–857 (2019).

Schrauf, C. & Call, J. Great apes use weight as a cue to find hidden food. Am. J. Primatol. 73, 323–334 (2011).

Schmidt, G. F. & Cook, R. G. Mind the gap: Means–end discrimination by pigeons. Anim. Behav. 71, 599–608 (2006).

Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 9, 625–636 (2002).

Gibbs, R. W. Embodiment and Cognitive Science (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Haddara, N. & Rahnev, D. The impact of feedback on perceptual decision-making and metacognition: Reduction in bias but no change in sensitivity. Psychol. Sci. 33, 259–275 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed by AAS, KNK and MAC. Testing was conducted by KNK and MAC. AAS, KNK and MAC analysed and visualised the data. MAC and AAS coded the videos. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AAS and MAC. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smirnova, A.A., Cheplakova, M.A. & Kubenko, K.N. Some Hooded crows (Corvus cornix) understand how a loose string works. Sci Rep 15, 15569 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99778-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99778-z