Abstract

The carbonation of steel slag (SS) can enhance its performance while capturing CO2. The synergistic effect of combining multi-solid waste materials improves SS’s carbon sequestration efficiency, thereby contributing to reduce carbon emissions. This study investigates the synergistic carbonation mechanism of SS when combined with calcium carbide slag (CCS) and desulfurization gypsum (DG) under various water-to-binder ratios (w/bs). The mineral evolution, carbon sequestration performance, and carbon footprint of the multi-solid waste composite system are comprehensively analyzed. The results indicate that, at different w/bs, most SS-CCS-DG composite pastes exhibit a significant strength increase after carbonation compared to carbonated SS paste. Specifically, the strength of the 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG paste is 44% and 60% higher than that of carbonated SS pastes at 0.15 and 0.3 w/bs, respectively. Carbon sequestration and carbon footprint analysis show that after carbonation, the composite system effectively sequesters 12.2% CO2, with an actual carbon sequestration rate surpassing 70% of its theoretical value. Compared to the SS system, the composite system achieves a higher negative carbon emission of -279.93 kg CO2/t.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The carbon neutrality challenge has accelerated carbon reduction efforts in the construction industry. Cement, a widely used building material, emits significant CO2-laden flue gas during production1,2.Producing one ton of cement releases approximately 616.6 kg of CO23. In recent years, reducing the use of cement clinker and recycling industrial flue gases have emerged as key research directions for carbon reduction. Steel slag, the main solid waste from steelmaking4,5, exceeds 100 million tons annually in China. However, its utilization rate is below 30%6,7,8. Steel slag contains hydraulic minerals, including dicalcium silicate (C2S) and tricalcium silicate (C3S), with cementitious properties9. However, the recycling of steel slag as a cementitious material is limited, with it being primarily used in small amounts to replace cement. This limitation stems partly from the slow hydration of steel slag, dominated by C2S10. Additionally, the high presence of free calcium oxide (f-CaO) in steel slag can cause harmful expansion11.

Steel slag, a large-scale alkaline waste, can capture and store CO2. Carbonation reduces the content of f-CaO in steel slag, which decreases its expansion and mitigates CO2 emissions12. Several studies have shown that accelerating carbonation enhances steel slag performance while sequestering CO213,14,15. Recent studies have focused on water’s influence on steel slag carbonation, partly due to the complex reaction kinetics of the gas-liquid-solid system. Claudel et al.16 suggested that gas dissolution and diffusion in water are more efficient, while the gas-solid reaction is limited by diffusion resistance, increasing the gas-liquid-solid reaction rate. For steel slag used as a cementitious material, the water-to-binder ratio (w/b) affects pore structure, which influences CO2 diffusion and carbonation. A higher w/b (> 0.3) increases pore volume, aiding CO2 diffusion. However, He et al.17 found that excessive water can block pores due to capillary forces, limiting CO2 diffusion. Moreover, high porosity from an excessive w/b weakens the cementing effect of carbonation products and impairs their mechanical properties18. A low w/b (< 0.2) reduces porosity and increases structural density, thereby improving early strength. The smaller pore structure also enhances water-CO2 contact, boosting solubility and promoting carbonation19. However, an excessively low w/b reduces the solubility of active mineral ions (e.g., Ca2+), limiting carbonation efficiency20.

The synergistic use of multiple solid wastes has become a widely studied approach for steel slag-based binders in recent years. Industrial solid wastes, such as fly ash21,22,27, slag23,24, and red mud25,26, exhibit cementitious properties, making them ideal for synergistic use with steel slag. Zhang et al.27 explored the synergistic effects of steel slag, red mud, blast furnace slag, and fly ash in cementitious materials. The results showed that multi-solid waste synergy enhanced the participation of low-activity calcium silicate in steel slag during hydration, promoting the formation of additional C-S-H gel. Duan et al.28 observed similar effects, where synergistic treatment of fly ash and flue gas desulfurization gypsum with steel slag yielded comparable results. Similarly, the ternary system formed by granular blast furnace slag, fly ash, and steel slag significantly mitigated the hydration deficiency seen in a single steel slag system29. To address the slow carbonation reaction and low carbon sequestration efficiency of steel slag, previous studies have applied waste synergy to enhance its carbonation. Ma et al.30 found that synergistic carbonation of steel slag and calcium carbide slag promoted carbonation by raising the pH of the system. This facilitated the ex situ dispersion of carbonation products, thus avoiding in situ particle aggregation and the formation of a covering layer. Wang et al.31 found that in a steel slag-desulfurization gypsum composite, desulfurization gypsum acted as a catalyst, facilitating the transformation of C12A7 in steel slag to calcite and Mc, further enhancing its carbonation. In comparison with single-component solid waste carbonation systems, this study demonstrates a 73% improvement in carbonation efficiency through the synergistic effects of multiple solid wastes (SS/CCS/DG)32.

This study combines the calcium carbide slag and desulfurization gypsum with steel slag. The mixtures were molded with low w/bs (0.1–0.2) and high w/bs (0.3–0.4). They were then cured in a CO2 environment. The enhancement of carbonation in the steel slag-calcium carbide slag-desulfurization gypsum composite was analyzed through strength testing, phase analysis, and thermal analysis. Additionally, the carbon sequestration behavior and carbon footprint of the system were assessed.

Materials and methods

Materials

The raw materials used in this study are steel slag (SS) from Xinpu Steel Plant, Anyang, Henan, calcium carbide slag (CCS) from Haohua Aerospace Chemical Co., Ltd., and desulfurization gypsum (DG) from Zhongfu Power Co., Ltd. All raw materials were milled into powder using an SM500 × 500 ball mill. The particle size of all raw materials is below 75 μm. The chemical composition and mineral phases of the four raw materials were determined using an S2 RANGER X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF) and a D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrument. The results are presented in Table 1; Fig. 1.

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the raw materials. The main mineral phases in SS include Mayenite (Ca12A7), Calcite (CaCO3), Portlandite (Ca(OH)2), Hatrurite (Ca3SiO5), Larnite (Ca2SiO4), and the RO phase (a solid solution of CaO, MgO, FeO, and MnO)33,34. The main mineral phases in DG and CCS are CaSO4·2H2O and Ca(OH)2, respectively.

Mix proportions

Table 2 presents the mix proportions of the SS and SS-CCS-DG composite systems. The experimental design included different solid waste incorporation ratios, w/bs, and curing methods. The solid waste incorporation ratios were determined using an L9 (33) orthogonal experimental design, with CCS levels of 3%, 5%, and 7%, and DG levels of 2%, 4%, and 6%. The range of 3–7% CCS content was chosen based on the typical Ca(OH)₂ content (40–60 wt%) in industrial by-products, which ensures that the system’s pH remains within the optimal range of 11.5–12.3 for carbonation reactions. The DG content range of 2–6% was chosen based on preliminary experimental results: when DG exceeds 6%, early ettringite formation exceeds 15 vol%, leading to specimen expansion and cracking. A variance analysis showed that the F-values for the factors’ effect on strength were all > 4.0 (p < 0.05), confirming the statistical significance of the selected factor levels.”

The w/bs were selected from the ranges 0.1–0.2 and 0.3–0.4, with specific values of 0.15 and 0.3 used in the orthogonal experiment. The choice of water-to-binder ratios of 0.15 and 0.3 was based on two main criteria: (a) the critical flowability of the mortar (according to ASTM C1437, 0.15 corresponds to a slump < 50 mm, and 0.3 corresponds to a range of 120–150 mm); (b) the key turning point in the porosity-permeability relationship. This range is suitable for characterizing the variation in CO₂ diffusion coefficients between 10⁻¹² and 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s. The curing methods included standard environment curing (RH ≥ 65%, 20 ± 2 °C) for 3 and 28 days, and CO2-environment curing (20 ± 3% CO2, RH ≥ 65%, 20 ± 2 °C) for 24 h. This was followed by standard curing for 3 and 28 days.

Molding and test methods

Molding method

The SS, CCS, and DG powders were uniformly mixed using a paste stirrer. Samples were prepared with high and low w/bs. For the high w/b samples, the mixture was poured into molds, allowed to harden, and demolded to obtain 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm cubic specimens. For the low w/b samples, the mixture was compacted in a molding press. The wet powder was placed in a pressure molding mold, compacted, and then demolded to obtain 50 mm × 50 mm cylindrical specimens. Figure 2 illustrates the mold and molding methods.

Test methods

The compressive strength of the samples at 3 and 28 days was measured according to GB/T 17671 − 1999 Cement Mortar Strength Test Method (ISO Method)35. The mineral phases were analyzed using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE XRD instrument (scan range: 5°-80°). The degree of carbonation and carbon sequestration were evaluated using a Netzsch TGA209F1 thermogravimetric analyzer (30–1000 °C, 20 °C/min).

Results and discussion

Compressive strength

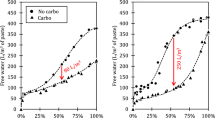

Figure 3 shows the compressive strength of SS pastes under different w/bs. The compressive strength of the low w/b group (SL) and high w/b group (SH) samples under standard curing conditions is generally similar. Although the SL group has fewer pores due to residual water after hydration, the hydration degree of SS is insufficient, and its strength does not exhibit a significant improvement compared to the SH group samples. In the CO2 environment, the compressive strength of the low w/b group (CL) samples is much higher than that of the high w/b group (CH) samples. At a w/b of 0.15, the 28-day strength of CL-S1 samples reaches 42.4 MPa, which represents nearly a 50% increase compared to the non-carbonated SL-S1 samples (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the highest strength sample in the high w/b group, CH-S2, exhibits only a 10% increase in strength compared to the non-carbonated SH-S2 sample.

Figure 4 shows the compressive strength of multi-solid waste composite SS pastes at w/bs of 0.15 and 0.3. The results demonstrate that most multi-solid waste composite SS pastes show significant improvements in compressive strength at both 3 and 28 days, with a more noticeable increase at 28 days. Among them, the compressive strength of the CL-A6 sample (w/b = 0.15) and the CH-B6 sample (w/b = 0.3) are 61.1 MPa and 28.5 MPa, respectively, substantially higher than the carbonated SS pastes at the same w/bs (CL-S1: 42.4 MPa; CH-S0: 17.8 MPa) and non-carbonated composite SS pastes at the same proportions (SL-A6: 28.4 MPa; SH-B6: 16.5 MPa). This suggests that the composite mix proportions enhance the carbonation process of SS. Further comparison of strength improvements under different w/bs shows that the sample with a 0.3 w/b achieved a 60% improvement, surpassing the 44% improvement achieved at a 0.15 w/b. This can be attributed to the higher w/b, which facilitates the carbonation reaction by increasing the porosity and enhancing CO2 diffusion.

Mineral phase

Figure 5 shows the XRD patterns of carbonated and non-carbonated SS pastes at w/bs of 0.15 and 0.3. In the carbonated samples, the diffraction peak intensity of Calcite (CaCO3) is stronger than that of the non-carbonated samples, whereas the intensities of Mayenite (C12A7), Portlandite (Ca(OH)2), Hatrurite (C3S), and Larnite (C2S) are significantly reduced. This suggests that carbonation primarily occurs through the carbonation of active minerals and the hydration product Ca(OH)2. Further comparison shows that in the 0.3 w/b sample (CH-S0), the intensity of Calcite’s diffraction peak is much lower than in the 0.15 w/b carbonated sample (CL-S1), whereas the diffraction peaks of C12A7, Ca(OH)2, C2S and C3S remain relatively strong. This indicates that the carbonation reaction was not fully completed at the higher w/b.

Figure 6 shows the XRD patterns of SS pastes and multi-solid waste composite SS pastes. In Fig. 6(a), the mineral phases of the non-carbonated SL-A6 and SH-B6 samples mainly consist of Mayenite (C12A7), Portlandite (Ca(OH)2), Hatrurite (C3S), Larnite (C2S), AFt (C3A.3CaSO4.32H2O), and Hemicarboaluminate (Hc: C3A.0.5CaCO3.0.5Ca(OH)2.11.5H2O). In contrast, the carbonated CL-A6 and CH-B6 samples exhibit diffraction peaks for Monocarbonate (Mc: C3A.CaCO3.11H2O) and gypsum, while the intensities of C3S, C2S, C12A7, Ca(OH)2, AFt, and Hc are significantly reduced. This suggests that the hydration products, such as Ca(OH)2, from C2S and C3S react with CO2 to form Hc. Meanwhile, the hydration of C12A7 generates AFt, both of which act as intermediates in the formation of Mc and gypsum. In Fig. 6(b), the carbonation products in the CL-A6 and CH-B6 samples are primarily CaCO3 and Mc, whereas the carbonation products in CL-S1 and CH-S0 are predominantly Calcite. This confirms that in a CO2 environment, CCS and DG facilitate the transformation of C12A7 in SS to Mc. Further comparison of the mineral phases in multi-solid waste SS pastes with w/bs of 0.15 and 0.3 reveals that the diffraction intensities of the carbonation products in the 0.3 w/b sample (CH-B6) are higher than those in the 0.15 w/b sample (CL-A6). This is due to the higher water content, which facilitates the carbonation reaction and aligns with the observed strength variation patterns.

Mineral changes in the SS system primarily result from the combined effects of the hydration and carbonation reactions of alkaline minerals (C3S, C2S), as well as the pozzolanic reaction between the silica gel formed during carbonation and Ca(OH)236. Notably, the degree of carbonation plays a key role in these reactions37. In the SS-CCS-DG system, DG promotes the formation of AFt and Hc, which further react with CO2 to produce CaCO3 and Mc38. The Ca(OH)2 in CCS reacts with CO2 to form CaCO3, thereby reducing the excessively high pH in the system. This reduction in pH prevents the over-dissolution of Ca(OH)2, which would otherwise impede SS hydration39.

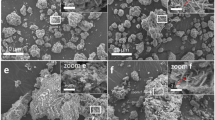

TGA

Figure 7 presents the TG-DTG curves of both carbonated multi-solid waste composite SS pastes and carbonated SS pastes, revealing the progressive decomposition of minerals as the temperature increases. The decomposition of C-S-H, AFt, and Mc primarily occurs below 200 °C31, while the mass loss in the 400–500 °C range is mainly due to the dehydration of Ca(OH)240. The mass loss between 600 and 800 °C is attributed to the decarbonation of CaCO341. The mass loss above 800 °C is primarily associated with the decomposition of gypsum. Examining the DTG curve between 0 and 200 °C, CL-S1 and CH-S0 exhibit significant AFt decomposition peaks. In contrast, CL-A6 and CH-B6 show Mc decomposition peaks, indicating that DG has facilitated the carbonation of AFt to Mc in SS. The decomposition peaks of C-S-H and the corresponding mass loss in CL-A6 and CH-B6 are notably higher than those in CL-S1 and CH-S0, suggesting a higher degree of hydration in the composite system. Additionally, the higher mass loss of Ca(OH)2 further confirms this. Ca(OH)2 in CCS, Ca(OH)2 formed during SS hydration, and AFt generated by DG and SS all react with CO2, leading to the formation of CaCO3. The formation of CaCO3 in the cementitious system facilitates the generation of C-S-H gel42,43. The mass loss of C-S-H and CaCO3 follows the order: CH-B6 > CL-A6 > CH-S0 > CL-S1.

To visually compare the enhanced synergistic effects of SS-DG-CCS, the degrees of hydration and carbonation of the samples were characterized. Given the substantial amount of Ca(OH)2 in CCS, using its content to measure hydration would lead to significant errors. Therefore, the degrees of hydration and carbonation were evaluated by measuring the chemically-bonded water and CaCO3 contents. Table 3 presents the chemically-bonded water and CaCO3 contents, as determined from the TGA results. As shown in Table 3, the chemically-bonded water content follows this order: CH-B6 (32.87%) > CL-A6 (20.16%) > CH-S0 (18.65%) > CL-S1 (13.29%). Similarly, the CaCO3 content follows the order: CH-B6 (27.98%) > CL-A6 (15.23%) > CH-S0 (10.91%) > CL-S1 (8.40%). These results confirm that the composite samples (89% SS-5% CCS-6% DG) exhibit a higher degree of hydration and carbonation.

Based on the above analysis, in the SS-CCS-DG composite system under a CO2 environment, part of the Ca(OH)2 in CCS accelerates the hydration of C3S and C2S in SS or reacts with DG to form AFt, while another portion reacts with CO2 to produce CaCO3. The intermediate products AFt and Hc, formed by the reaction between DG, C12A7 in SS, and Ca(OH)₂ in CCS, are consumed during carbonation and converted into CaCO3. Subsequently, CaCO3 reacts with the remaining AFt and Hc to form Mc, along with a small amount of gypsum.

Carbon sequestration effect evaluation

Figure 8 shows the TGA results of the 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG system at a w/b of 0.3, both before and after carbonation (SH-B6 & CH-B6). As seen in the figure, SH-B6 shows only slight changes in mass loss and decomposition rate between 550 and 800 °C. In contrast, the CH-B6 exhibits significant mass loss and a higher decomposition rate in this range. This temperature range primarily corresponds to the decomposition of CaCO3, based on empirical data. From the thermogravimetric data, the mass ratio of CaCO3 and CO2 in the two samples are: SH-B6 contains 0.22% CaCO3 and 0.096% CO2, while CH-B6 contains 27.98% CaCO3 and 12.2% CO2. Table 4 further presents the carbon sequestration performance of CH-B6, including the theoretical and actual carbon sequestration rates, carbon sequestration degree, and carbonation efficiency. The results show that the actual carbon sequestration rate of CH-B6 (36.3%) is over 70% of its theoretical value (49.43%). Its carbon sequestration degree and carbonation efficiency reach 82.21% and 236.21%, respectively, indicating that CH-B6 has a high CO2 sequestration capacity.

Carbon footprint analysis of composite systems

The carbon footprint of the multi-solid waste composite SS pastes was evaluated, considering the entire process, including raw materials, production, and yield. The system boundary for carbon emissions (CO2 emissions, COE) defines each material’s contribution to COE and its associated costs. The functional unit of this study is 1 ton of multi-solid waste composite SS pastes. The analysis framework follows current standards and methods outlined in relevant literature (Fig. 9; Table 5).

Table 5 summarizes the COE factors for materials and processes.Since SS, CCS, and DG are waste materials, their COE factors are assumed to be 0 kg CO2 eq/ton The COE factor for water is 2 kg CO2 eq/ton, according to ICE V 3.0. The stirring process involves electricity consumption, with the COE factor calculated based on electricity data from Henan. The COE factor for electricity is 2.85 kg CO2 eq/kWh, and the stirring machine has a power consumption of 0.37 kW. Therefore, the COE factor for the preparation process (Cefc) is 1.0545 kg CO2 eq/h. The stirring time is 4 min, and the batch yield is 0.5 kg, resulting in a production rate (CE) of 0.0075 t/h. This calculation provides an estimate of the COE associated with material preparation, accounting for all major factors influencing environmental impact.

One functional unit paste COE is calculated as follows:

Note

\(\:{\text{C}\text{O}\text{E}}_{total}:\)

Total COE equivalent (kg CO2/t);

\(\:{\text{C}\text{e}\text{f}}_{mi}:\) The COE of materials (kg CO2/kg);

\(\:{M}_{i}:\:\)Quality of the materials used (kg /t of paste);

\(\:{\text{C}\text{e}\text{f}}_{p}:\:\)Electrical consumption of COE factor(kg CO2/kg);

\(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{p}}:\) Electrical consumption of the coating process (kW h/t paste).

Figure 10 shows the carbon footprint of carbonated SS and multi-solid waste composite SS pastes. All the samples exhibit negative carbon emissions after carbonation. Compared to SS carbonation, the CL-A6 and CH-B6 samples of the 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG composite system show a lower COE, which is attributed to the high carbon sequestration of the multi-solid waste composite SS. Further comparison reveals that CH-B6 achieves the lowest COE. This indicates that the 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG composite system with a 0.3 w/b is more effective in reducing COE. The COE of CH-S0 is higher than that of CL-S1, suggesting that an appropriate amount of water is beneficial for CO2 diffusion and dissolution, thus promoting the carbonation reaction.

Conclusion

This study explored the carbonation performance of the SS-CCS-DG composite system, focusing on its synergistic effects, carbonation enhancement mechanisms, and a comprehensive evaluation of its carbon sequestration and carbon footprint. The key findings are as follows:

(1) The combination of CCS and DG with SS resulted in a notable synergistic carbonation effect. After carbonation, the compressive strength of the composite paste (89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG) increased, showing higher 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths compared to the carbonated SS samples. At w/bs of 0.15 and 0.3, the 28-day strength of the composite pastes improved by 44% and 60%, respectively, indicating significant enhancement.

(2) The uncarbonated 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG samples contained only 0.22% CaCO3 and 0.096% CO2, whereas the carbonated samples contained 27.98% CaCO3 and 12.2% CO2. The system achieved an actual carbon sequestration rate exceeding 70% of its theoretical value, with a carbon sequestration degree of 106.21% and a carbonation efficiency of 236.21%.

(3) Carbon footprint analysis revealed that the 89%SS-5%CCS-6%DG system resulted in the highest negative carbon emission (-279.93 kg CO2/t) compared to the SS system. This highlights the superior CO2 emission reduction capability of the multi-solid waste composite system.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Gao, T. et al. Evolution and projection of CO2 emissions for China’s cement industry from 1980 to 2020. Renew. Sust Energy Rev. 74, 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.02.006 (2017).

Lin, B. & Zhang, Z. Carbon emissions in China’s cement industry: A sector and policy analysis. Renew. Sust Energy Rev. 58, 1387–1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.348 (2016).

Noviani, L., Haryono, E., Supartono, W., Sahali, I. & Juliani, F. E. Environmental impact analysis of PCC cement products (Portland composite Cement) using LCA (Life cycle Assessment). In IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1190 (1), 012003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1190/1/012003 IOP Publishing (2023)

Gao, W. et al. Comprehensive utilization of steel slag: A review. Powder Technol. 422, 118449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118449 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Novel low-cost steel slag porous ceramic-based composite phase change material: an innovative strategy for comprehensive utilization of steel slag resources. Ceram. Int. 49 (22), 35466–35475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.08.225 (2023).

Guo, J., Bao, Y. & Wang, M. Steel slag in China: treatment, recycling, and management. Waste Manag. 78, 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.04.045 (2018).

Xing, Y. & Wang, B. Modification of phases evolution and heavy metal immobilization in alkali-activated MSWI FA by the incorporation of converter steel slag. J. Build. Eng. 78, 107573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107573 (2023).

Santos, W. F. et al. Sodium oxalate activation of basic oxygen furnace slag for Building materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 198, 107174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107174 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Ling, T. C., Shi, C. & Pan, S. Y. Characteristics of steel slags and their use in cement and concrete—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 136, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.04.023 (2018).

Shi, C. Steel slag—its production, processing, characteristics, and cementitious properties. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 16 (3), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2004)16:3(230) (2004).

Rojas, M. F. & De Rojas, M. S. Chemical assessment of the electric Arc furnace slag as construction material: expansive compounds. Cem. Concr Res. 34 (10), 1881–1888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.01.029 (2004).

Liu, W., Teng, L., Rohani, S., Qin, Z., Zhao, B., Xu, C. C., … Liang, B. CO2 mineral carbonation using industrial solid wastes: A review of recent developments. Chem. Eng. J. 416, 129093 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129093(2021).

Ghouleh, Z., Guthrie, R. I. & Shao, Y. Production of carbonate aggregates using steel slag and carbon dioxide for carbon-negative concrete. J. CO2 Util. 18, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2017.01.009 (2017).

Mo, L. et al. Accelerated carbonation and performance of concrete made with steel slag as binding materials and aggregates. Cem. Concr Compos. 83, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.07.018 (2017).

Pan, S. Y., Adhikari, R., Chen, Y. H., Li, P. & Chiang, P. C. Integrated and innovative steel slag utilization for iron reclamation, green material production and CO2 fixation via accelerated carbonation. J. Clean. Prod. 137, 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.112 (2016).

Claudel, B. et al. Some problems in heterogeneous photochemistry. J. Photochem. 30 (1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2670(85)87003-9 (1985).

He, Z., Yang, H., Shao, Y. & Liu, M. Early carbonation behaviour of no-clinker steel slag binder. Adv. Cem. Res. 25 (6), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1680/adcr.12.00054 (2013).

Humbert, P. S. & Castro-Gomes, J. P. Influence of Temperature and CO2 Partial Pressure on Carbonation Curing for Cement-Free Steel Slag-Based Materials. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Sustainable Production and Use of Cement and Concrete: ICSPCC 2019 (pp. 243–250) June https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22034-1_28 Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2019).

Navarro, C., Díaz, M. & Villa-García, M. A. Physico-chemical characterization of steel slag. Study of its behavior under simulated environmental conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (14), 5383–5388. https://doi.org/10.1021/es100690b (2010).

Tu, M. et al. Aqueous carbonation of steel slag: a kinetics study. ISIJ Int. 55 (11), 2509–2514. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2015-142 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Potential and durability of supplementary cementitious material prepared by incineration fly Ash: Co-sintering and water-washing treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 496, 153992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.1539922 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of Woody biomass fly Ash and class F fly Ash as supplementary cementitious materials in mortar. Materials 17 (15), 3723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma171537233 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Effect of Diethanol-Isopropanolamine and typical supplementary cementitious materials on the hydration mechanism of BOF slag cement pastes. Buildings 14 (5), 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14051268 (2024).

Wu, Z., et al. Mechanical properties and environmental characteristics of the synergistic preparation of cementitious materials using electrolytic manganese residue, steel slag, and blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134480 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134480 (2024).

Chen, B., Li, B., Pang, L. & Liu, B. Study on the synergistic Preparation of supplementary cementitious materials from multiple solid wastes: bayer red mud and gold tailings. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12 (3), 112599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.112599 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Film-Forming property of cement paste with red mud as a supplementary cementitious material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36 (6), 04024104. https://doi.org/10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-1694 (2024).

Zhang, W., Hao, X., Wei, C., Liu, X. & Zhang, Z. Activation of low-activity calcium silicate in converter steelmaking slag based on synergy of multiple solid wastes in cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 351, 128925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128925 (2022).

Duan, S., Liao, H., Cheng, F., Song, H. & Yang, H. Investigation into the synergistic effects in hydrated gelling systems containing fly Ash, desulfurization gypsum and steel slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 187, 1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.241 (2018).

Zhang, J., Sun, N., Huo, Z. & Chen, J. Understanding the synergistic geopolymerization mechanism of multiple solid wastes in ternary geopolymers. J. Build. Eng. 95, 110295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110295 (2024).

Ma, Z., Liao, H. & Cheng, F. Synergistic mechanisms of steelmaking slag coupled with carbide slag for CO2 mineralization. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 105, 103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103229 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Carbonation of steel slag and gypsum for Building materials and associated reaction mechanisms. Cem. Concr Res. 125, 105893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.105893 (2019).

He, Y., et al. Utilization of steel slag in air pollution and greenhouse gas emission reduction-Application,Mechanism and Challenge: A Review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 12 (11), 114090 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114090 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Immobilisation of high-arsenic-containing tailings by using metallurgical slag-cementing materials. Chemosphere 223, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.030 (2019).

Kong, Y., Wang, P. & Liu, S. Microwave pre-curing of Portland cement-steel slag powder composite for its hydration properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 189, 1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.088 (2018).

Standardization Administration of China. Test Method for Strength of Cement Mortar (ISO Method) (GB/T 17671 – 1999) (China Standards, 1999).

Song, Q., Guo, M. Z., Wang, L. & Ling, T. C. Use of steel slag as sustainable construction materials: A review of accelerated carbonation treatment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 173, 105740. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2021.105740 (2021).

Fang, Y., Shan, J., Wang, Q., Zhao, M. & Sun, X. Semi-dry and aqueous carbonation of steel slag: characteristics and properties of steel slag as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 425, 135981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135981 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Study on Preparing sustainable limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) through CO2-active treatment of municipal solid waste incineration fly Ash (IFA). Constr. Build. Mater. 438, 137040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137040 (2024).

Huang, G. et al. Simultaneous utilization of mine tailings and steel slag for producing geopolymers: Alkali-hydrothermal activation, workability, strength, and hydration mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 414, 135029 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.1350299 (2024).

Teng, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, Z., Xue, J. & Guan, X. Effect of triethanolamine on the chloride binding capacity of cement paste with a high volume of fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 315, 125612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125612 (2022).

Chang, J., Xiong, C., Zhang, Y. & Wang, D. Foaming characteristics and microstructure of aerated steel slag block prepared by accelerated carbonation. Constr. Build. Mater. 209, 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2019.03.077 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Influence of the combination of calcium oxide and sodium carbonate on the hydration reactivity of alkali-activated slag binders. J. Clean. Prod. 171, 622–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2017.10.077 (2018).

Burciaga-Díaz, O., Betancourt-Castillo, I. E., Montes-Escobedo, M. E. & Escalante-García, J. I. One-part pastes and mortars of CaO-Na2CO3 activated blast furnace slag: microstructural evolution, cost and CO2 emissions. Constr. Build. Mater. 368, 130431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130431 (2023).

Hammond, G. & Jones, C. Inventory of Carbon & Energy (ICE) Version 3.0 (University of Bath, Department of Mechanical Engineering, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51508191), the Construction Science and Technology Project of Hubei Province (JK 2024116), the Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (242102321058, 242102321175) and the Colleges Young Teacher Training Project of Henan Province (2023GGJS074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.W: Writing—original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis; H.Z: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; S.L: Data curation; Y.S: Data curation; H.B: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; J.M: Writing—review and editing;All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Zheng, H., Li, S. et al. Study on carbonation behavior and carbon footprint of steel slag-calcium carbide slag-desulfurization gypsum composite system. Sci Rep 15, 15199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99803-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99803-1