Abstract

Nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) and skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) are widely accepted surgical options for breast cancer patients undergoing immediate reconstruction. However, the impact of preserving the nipple–areolar complex on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) remains uncertain, particularly in clinically matched settings. This retrospective study included patients who underwent unilateral NSM or SSM followed by immediate implant-based breast reconstruction at Hubei Cancer Hospital between January 2022 and January 2024. Patients were propensity score matched (2:1) based on age, body mass index, preoperative breast size, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, implant plane, and postmastectomy radiation therapy. PROs were assessed using the BREAST-Q (version 2.0) and the decision regret scale. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted to identify predictors of satisfaction and regret. A total of 87 patients were included after matching (NSM: n = 58; SSM: n = 29). NSM patients reported significantly higher satisfaction with breasts (mean 58.1 vs. 52.9, P = 0.038) and sexual well-being (mean 52.4 vs. 38.9, P = 0.035). Although psychosocial well-being and decision regret showed favorable trends in the NSM group, differences were not statistically significant. Multivariate analysis revealed that reduction in breast size was significantly associated with decreased satisfaction and psychosocial well-being, while increased breast size was linked to greater decision regret. No significant differences were observed in complication rates between groups. Notably, none of the SSM patients received nipple reconstruction during follow-up. NSM was associated with greater satisfaction in breast and sexual well-being compared to SSM in matched breast cancer patients undergoing implant-based reconstruction. These findings support prioritizing NSM when oncologically feasible and highlight the potential role of delayed nipple reconstruction and expectation management in improving postoperative satisfaction for SSM patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in women worldwide, with an estimated 2,308,897 new cases reported in 20221. Early or resectable breast cancer, which is considered potentially curable, encompasses stages I-IIB and select stage IIIA cancers, particularly T3-N1 tumors. Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment but often results in cosmetic deformities or the complete loss of the breast2. To address these concerns, breast reconstruction offers a way to restore breast shape after lumpectomy or mastectomy2,3. While disease control remains the primary focus of treatment, improving cosmetic outcomes has become increasingly important for mitigating the physical and emotional trauma faced by patients4.

With advancements in surgical techniques, traditional Halsted mastectomy has evolved into modified radical mastectomy, aiming to reduce patient trauma5. In pursuit of less invasive options, procedures such as skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM), which retains most of the skin envelope, and nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM), which also preserves the nipple‒areola complex (NAC), have been developed5. Eligibility for NSM is determined primarily by oncologic criteria, including tumor size, proximity to the nipple, and breast cancer subtype6. When NSM is contraindicated due to safety concerns or aesthetic factors such as macromastia or severe ptosis, SSM is generally performed, which involves removal of the NAC6.

Both NSMs and SSMs are now widely acknowledged to have comparable oncologic safety7,8,9,10,11. However, NSM is associated with a greater incidence of specific complications, including infection, nipple or flap necrosis, nipple malposition, and asymmetry8,12,13,14,15,16,17. While several recent studies have compared patient-reported outcomes (PROs) between NSMs and SSMs, their findings remain inconsistent18,19,20,21. The results of such studies have been mixed and sometimes difficult to interpret because of small sample sizes, heterogeneous cohorts, and different PRO measures.

Therefore, this study focuses on patients eligible for either NSM or SSM based on oncologic criteria, aiming to evaluate the impact of NAC preservation on PROs under matched clinical circumstances.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Hubei Cancer Hospital Review Board (Approval No. LLHBCH2023YN-046). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

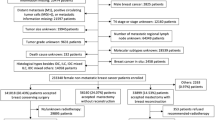

This study included patients who underwent unilateral mastectomy followed by immediate implant-based breast reconstruction at Hubei Cancer Hospital between January 2022 and January 2024. Patients were divided into two groups: the NSM group, comprising reconstructed breasts following nipple-sparing mastectomy (with NAC preservation), and the SSM group, comprising reconstructed breasts following skin-sparing mastectomy with NAC excision (Fig. 1). At the time of follow-up, none of the patients in the SSM group had undergone nipple reconstruction or nipple–areolar tattooing. A total of 176 eligible patients were included in this process.

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Patients aged ≥ 18 years who underwent NSM or SSM.

-

2.

Immediate unilateral implant-based breast reconstruction was performed at the time of surgery.

-

3.

Completion of the preoperative evaluation and at least 6 months of postoperative follow-up.

-

4.

Availability of complete PRO data (BREAST-Q and DRS).

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Patients not eligible for NSM or SSM.

-

2.

Bilateral reconstruction.

-

3.

Patients who underwent autologous tissue reconstruction, either alone or in combination with implants.

-

4.

Two or more reconstructive procedures.

-

5.

Implant removal during follow-up.

-

6.

Incomplete follow-up or loss to follow-up.

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching (PSM) is a widely used statistical technique designed to minimize confounding bias in nonrandomized studies by matching individuals with similar distributions of covariates22. In retrospective analyses, where interventions are not randomly assigned, conventional statistical approaches may yield biased estimates owing to baseline imbalances. PSM addresses this issue by estimating the likelihood (propensity score) of everyone receiving a specific treatment based on observed covariates and then matching participants with comparable scores across treatment groups.

Patients were divided into two cohorts: the NSM cohort and the SSM cohort. To minimize potential confounding factors, a propensity score-matched analysis was conducted via a 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching method without replacement. The matching covariates included age, body mass index (BMI), preoperative breast size, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT), implant plane and postmastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT). A total of 87 patients were enrolled, including 58 in the NSM group and 29 in the SSM group. The distribution of the matched cohorts was evaluated visually via histogram and jitter plot (Fig. 2).

The matching covariates included age, BMI, preoperative breast size, implant plane, NACT and PMRT. The left panel illustrates the distribution of propensity scores among treated (NSM) and control (SSM) units, showing both matched and unmatched observations. The right panels display histograms of the propensity scores for treated (NSM) and control (SSM) groups before (Raw) and after (Matched) propensity score matching. Matching substantially improved the balance of propensity scores between treated (NSM) and control (SSM) units, indicating successful covariate adjustment through PSM.

Outcomes of interest

The BREAST-Q was developed by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the University of British Columbia, with its initial introduction by Pusic et al. in 200923,24. It is a validated PRO instrument designed to assess the impact and effectiveness of breast surgery, including reconstruction-specific outcomes24,25. Decision regret refers to negative emotions, such as distress or remorse, that patients may experience after making a medical decision26. Postmastectomy breast reconstruction, with its complex array of options, is particularly prone to decision regret27. Previous studies have identified dissatisfaction with preoperative information and limited shared decision-making as key contributors to this regret28,29.

PROs were assessed via the BREAST-Q (Chinese version 2.0) and the DRS. The BREAST-Q reconstruction module focused on satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial well-being, and sexual well-being, with patients completing the questionnaire at least 6 months postoperatively. Subscale scores were converted to summary scores ranging from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicated greater satisfaction or quality of life. A difference of 4 points or more in the Q score was considered clinically significant30. The DRS evaluated regret regarding the decision to undergo NSM or SSM, with scores ranging from 0 to 100, where higher scores reflected greater regret.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics and therapy-related variables were compared between the SSM and NSM cohorts via two-sided Student’s t test or the Mann‒Whitney rank sum test for continuous variables and the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The BREAST-Q domain score and the DRS score are reported as the means (standard deviations [SDs]) and medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]), with differences in scores assessed via the Mann‒Whitney rank-sum test. Surgical complication rates were compared via the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. After excluding variables used for PSM, potential factors associated with differences in outcomes were included as independent variables in the univariate linear regression analyses, with BREAST-Q domain scores (breast satisfaction, psychosocial well-being, and sex well-being) and the DRS scores as dependent variables. Variables with a P value < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate linear regression models. All tests were two-sided, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted via R statistical software (version 4.2.3).

Results

A total of 176 patients who underwent immediate implant-based breast reconstruction following NSM or SSM and completed both the postoperative BREAST-Q and DRS questionnaires were included in the unmatched cohort. After PSM, 87 patients (58 in the NSM group and 29 in the SSM group) were included in the final analysis.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were compared between the reconstruction subgroups (Table 1). The analysis sample had a mean age of 41.6 years and a mean BMI of 21.3 kg/m2. 69% of patients were diagnosed with stage I–II cancer. Additionally, 85% of patients had a preoperative breast cup size of A or B. 94.3% of patients were married, and 48.3% of patients had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The two cohorts were similar in terms of age, BMI, and all sociodemographic factors. Clinical factors such as preoperative breast size, menopausal status, and family history of breast cancer were not significantly different. However, significant differences were found in terms of breast cancer stage (P = 0.014) and molecular subtypes (P = 0.035). These findings establish a comprehensive baseline for analyzing treatment and outcome disparities.

The data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise specified. NSM, nipple-sparing mastectomy with reconstruction; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy with reconstruction; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index. *P value calculated with two-sided t test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test.

Therapy-related variables

Table 2 compares therapy-related variables between the two cohorts. Most variables, including NACT, PMRT, implant plane, chemotherapy, changes in breast size, implant volume, surgery duration, and cost, did not significantly differ (P > 0.05). However, notable differences were observed in axillary operation, with SSM patients more likely to undergo both sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) (55.2% vs. 20.7%, P = 0.001).

Patient-reported outcomes

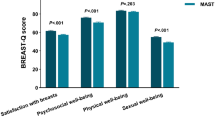

Satisfaction with breasts

The overall mean breast satisfaction score was 56.4, with the NSM cohort reporting higher satisfaction than the SSM cohort did (mean: 58.1 vs. 52.9, median: 58 vs. 52; P = 0.038) (Table 3; Fig. 3). When individual components of the breast satisfaction scale were evaluated, NSM patients reported significantly greater satisfaction than SSM patients did in several areas (Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, SSM patients reported lower satisfaction with breast size symmetry (mean: 2.4 vs. 2.7, P = 0.040), perceived naturalness of breasts as part of the body (mean: 2.5 vs. 2.8, P = 0.007), and breast symmetry in appearance (mean: 2.4 vs. 2.7, P = 0.033). Trends toward lower satisfaction in the SSM group were noted for clothed appearance (P = 0.064), bra-fit comfort (P = 0.060), and fitted clothing ability (P = 0.069), though these did not reach statistical significance.

Comparison of BREAST-Q domain scores and decision regret scores between NSM and SSM groups (boxplots). The Mann‒Whitney rank-sum test was used for comparisons between cohorts. *p < 0.05, NS: not significant. SB Satisfaction with Breasts, PWB psychosocial well-being, SWB sexual well-being, DRS Decision Regret Scale.

In univariable analysis, significant negative associations were observed for axillary operation (SLNB and ALND: β = −7.76, 95% CI − 14.65 to − 0.88, P = 0.028), reduced breast size (β = −12.21, 95% CI − 22.13 to − 2.29, P = 0.016), and increased breast size (β = −13.98, 95% CI − 26.46 to − 1.49, P = 0.029) (Table 4). In multivariable analysis, only reduced breast size remained significantly associated with lower breast satisfaction (β = −11.24, 95% CI − 21.5 to − 0.99, P = 0.032). SSM cohort, endoscopic-assisted mastectomy, and complications showed non-significant trends toward influence breast satisfaction in univariable analysis (all P > 0.05), but these associations attenuated after adjustment. Other variables, including incision type and chemotherapy, demonstrated no significant impacts in either analysis.

Psychosocial well-being

The overall mean psychosocial well-being score was 71.5, with the score trending lower in the SSM cohort (mean: 65.9 vs. 74.3, median: 64 vs. 71, P = 0.072), though not statistically significant. (Table 3; Fig. 3). Significant differences were observed in specific domains: Attractiveness (mean: 3.9 vs. 3.3, P = 0.031) and feeling feminine in clothing (mean: 4.1 vs. 3.7, P = 0.037) were significantly lower in the SSM group (Supplementary Table 2).

The reduction in breast size demonstrated a significant negative association in both univariable (β = −16.22, 95% CI − 29.99 to − 2.45, P = 0.022) and multivariable analyses (β = −16.43, 95% CI − 30.01 to − 2.85, P = 0.018), indicating a strong link between breast size reduction and poorer psychosocial well-being scores (Table 5). The SSM group showed a borderline non-significant trend toward lower psychosocial well-being compared to NSM in both analyses (univariable: β = −8.86, P = 0.064; multivariable: β = −8.58, P = 0.067).

Sexual well-being

The overall mean sexual well-being score was 47.9, with the NSM cohort reporting a higher score than the SSM cohort did (mean: 52.4 vs.38.9, median: 46 vs. 41; P = 0.035) (Table 3; Fig. 3). SSM patients reported significantly lower scores in two key domains: confidence about breast appearance when unclothed (mean: 1.9 vs. 2.7, P = 0.014), perceived sexual attractiveness when unclothed (mean: 2.0 vs. 2.7, P = 0.031) (Supplementary Table 3). Non-significant trends toward reduced satisfaction were observed for feeling sexually attractive in clothing (mean: 2.8 vs. 3.4, P = 0.072) and general sex-life satisfaction (mean: 2.8 vs. 3.3, P = 0.082).

SSM cohort was significantly associated with reduced sexual well-being in both univariable (β = −13.57, 95% CI − 24.29 to − 2.85, P = 0.014) and multivariable analyses (β = −11.68, 95% CI − 22.67 to − 0.7, P = 0.037) (Table 6). Increased breast size also showed strong negative associations with sexual well-being in univariable (β = −24.88, 95% CI − 45.05 to − 4.71, P = 0.016) and multivariable models (β = −23.28, 95% CI − 43.06 to − 3.49, P = 0.022). Endoscopic-assisted mastectomy demonstrated a borderline non-significant trend toward improved sexual well-being in univariable analysis (β = 17.14, P = 0.061), but this attenuated after adjustment (P = 0.143).

Decision regret scale

The decision regret score was numerically higher in SSM (mean: 29.1 vs. 21.4, median: 35 vs. 25, P = 0.118), but this difference lacked significance (Table 3; Fig. 3). Increased breast size demonstrated a significant positive association with higher decision regret in both univariable (β = 19.84, 95% CI 4.69–34.98, P = 0.011) and multivariable analyses (β = 18.62, 95% CI 3.58–33.66, P = 0.016), indicating that breast enlargement was strongly linked to greater regret (Table 7). The SSM cohort showed a borderline non-significant trend toward increased regret compared to NSM in univariable (β = 7.76, P = 0.064) and multivariable models (β = 6.91, P = 0.091).

Complications

No significant differences were found in the proportion or types of postoperative complications between the two cohorts (Table 8). The most common surgical complication in both cohorts was mastectomy skin necrosis/skin flap necrosis.

Discussion

Despite matching for key confounding variables—including age, BMI, preoperative breast size, NACT, implant plane, and PMRT—significant differences in PROs were still observed between the NSM and SSM groups. Specifically, the NSM group was associated with significantly higher satisfaction with breasts and sexual well-being. Although psychosocial well-being scores also tended to be higher in the NSM group, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Notably, none of the patients in the SSM group underwent nipple reconstruction, which may have contributed to their lower satisfaction scores. Multivariable analyses further identified changes in breast size—particularly reductions or increases—as independent predictors of decreased satisfaction across all BREAST-Q domains, as well as increased decision regret. While surgical complications did not differ significantly between the two cohorts, the type of mastectomy and the preservation of the NAC appeared to have a meaningful impact on PROs.

Metcalfe et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey study using the BREAST-Q to evaluate satisfaction in women who underwent risk-reducing mastectomy, including 53 NSM and 84 SSM cases18. Their findings indicated that women in the NSM group reported significantly greater satisfaction with breasts, overall outcomes, and sexual well-being than those in the SSM group did. In contrast, Van et al. compared 20 women who underwent prophylactic bilateral SSM with 25 women who underwent NSM and immediate implant-based breast reconstruction19. Interestingly, their results favored the SSM group in terms of BREAST-Q scores for breast satisfaction and overall outcomes. However, it is important to note that bilateral prophylactic mastectomy is uncommon in China, and all patients in our study were diagnosed with breast cancer, which may influence the generalizability of the findings in our cohort.

Romanoff et al. compared outcomes after unilateral or bilateral NSM with immediate reconstruction (n = 219) versus total mastectomy with reconstruction (n = 1647)31. Their study revealed that psychosocial and sexual well-being scores were significantly higher in the NSM group. However, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the NSM cohort underwent bilateral surgery, which may have influenced the findings. This factor could be a contributing variable to the observed differences in psychosocial and sexual well-being, although it did not impact satisfaction with breasts.

Bailey et al. performed a retrospective study using the BREAST-Q to evaluate satisfaction in women undergoing mastectomy with reconstruction (32 NSM and 32.

SSM)20. The authors found significantly higher mean postreconstruction scores in the NSM group within the satisfaction with breasts (p = 0.039) and the psychosocial well-being (p = 0.043)20. Building on these findings, our study not only confirmed the superior breast satisfaction associated with NSM but also extended the evaluation to include decision regret, offering a more comprehensive understanding of PROs in a propensity score-matched cohort.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design and small sample size limit generalizability. Second, selection bias is possible, as patients were not randomly assigned to NSM or SSM. Although PSM adjusted for baseline differences, it reduced the sample size and statistical power—for example, the power to detect a 5.2-point difference in breast satisfaction was only 45%. For other outcomes, including psychosocial well-being (d = 0.41), sexual well-being (d = 0.58), and decision regret (d = 0.40), the power ranged from approximately 62% to 87%. Third, none of the SSM patients received nipple reconstruction, which may have negatively affected satisfaction and contributed to group differences. It should be noted that SSM followed by delayed nipple reconstruction (e.g., using Star flap, CV flap, or pigmentation/tattoo techniques) might yield satisfaction levels comparable to NSM. Fourth, not all eligible patients completed the BREAST-Q, and potential response bias cannot be excluded. Finally, this single-center study in China may have limited generalizability due to differences in BMI, breast size, and cultural expectations compared to Western populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this propensity score–matched analysis demonstrated that NSM was associated with significantly higher satisfaction with breasts and sexual well-being compared to SSM in patients undergoing immediate implant-based breast reconstruction. Although psychosocial well-being and decision regret did not reach statistical significance, trends consistently favored the NSM group. Notably, none of the SSM patients in this cohort underwent nipple reconstruction, which may have contributed to the observed differences in satisfaction.

From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that, when oncologically appropriate, NSM should be prioritized to enhance postoperative quality of life and patient satisfaction. For patients requiring SSM, early planning for delayed nipple reconstruction may help mitigate dissatisfaction. Additionally, changes in breast size were strongly associated with reduced satisfaction and increased regret, highlighting the importance of managing patient expectations regarding volume outcomes during preoperative counseling. These insights may guide more individualized, patient-centered surgical decision-making in breast reconstruction practice.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy and institutional regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Munhoz, A. M., Montag, E., Filassi, J. R. & Gemperli, R. Current approaches to managing partial breast defects: the role of conservative breast surgery reconstruction. Anticancer Res. 34(3), 1099–1114 (2014).

Platt, J., Baxter, N. & Zhong, T. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. CMAJ 183(18), 2109–2116. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110513 (2011).

García-Solbas, S., Lorenzo-Liñán, M. & Castro-Luna, G. Long-term quality of life (BREAST-Q) in patients with mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189707 (2021).

Freeman, M. D., Gopman, J. M. & Salzberg, C. A. The evolution of mastectomy surgical technique: From mutilation to medicine. Gland Surg. 7(3), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2017.09.07 (2018).

Amador, R. O. et al. Bilateral implant-based breast reconstruction with unilateral radiotherapy: A matched cohort study comparing nipple-sparing mastectomy and skin-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 12(5), e5807. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000005807 (2024).

Yamashita, Y. et al. Long-term oncologic safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction. Clin. Breast Cancer 21(4), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2021.01.002 (2021).

Agha, R. A. et al. Systematic review of therapeutic nipple-sparing versus skin-sparing mastectomy. BJS Open 3(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50119 (2019).

Cho, J. H. et al. Oncologic outcomes in nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and total mastectomy with immediate reconstruction in women with breast cancer: A machine-learning analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 30(12), 7281–7290. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13963-w (2023).

Wu, Z. Y. et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of immediate breast reconstruction vs conventional mastectomy alone for breast cancer in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Surg. 155(12), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4132 (2020).

Costeira, B. et al. Locoregional recurrence in skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomies. J. Surg. Oncol. 125(3), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26725 (2022).

Wang, M., Huang, J. & Chagpar, A. B. Is nipple sparing mastectomy associated with increased complications, readmission and length of stay compared to skin sparing mastectomy?. Am. J. Surg. 219(6), 1030–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.09.011 (2020).

Henry, N. et al. Immediate prepectoral tissue expander breast reconstruction without acellular dermal matrix is equally safe following skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 93(2), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1097/sap.0000000000003945 (2024).

Lee, J. H., Choi, M. & Sakong, Y. Retrospective analysis between complication and nipple areola complex preservation in direct-to-implant breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 10(1), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-606 (2021).

Kracoff, S., Benkler, M., Allweis, T. M., Ben-Baruch, N. & Egozi, D. Does nipple sparing mastectomy affect the postoperative complication rate after breast reconstruction? Comparison of postoperative complications after nipple sparing mastectomy vs skin sparing mastectomy. Breast J. 25(4), 755–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13325 (2019).

Ito, H. et al. Risk factors for skin flap necrosis in breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction. World J. Surg. 43(3), 846–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4852-y (2019).

Santosa, K. B. et al. Comparing nipple-sparing mastectomy to secondary nipple reconstruction: A multi-institutional study. Ann. Surg. 274(2), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003577 (2021).

Metcalfe, K. A. et al. Long-term psychosocial functioning in women with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: Does preservation of the nipple-areolar complex make a difference?. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22(10), 3324–3330. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4761-3 (2015).

van Verschuer, V. M. et al. Patient satisfaction and nipple-areola sensitivity after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and immediate implant breast reconstruction in a high breast cancer risk population: Nipple-sparing mastectomy versus skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 77(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/sap.0000000000000366 (2016).

Bailey, C. R. et al. Quality-of-life outcomes improve with nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 140(2), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000003505 (2017).

Kim, H., Park, S. J., Woo, K. J. & Bang, S. I. Comparative study of nipple-areola complex position and patient satisfaction after unilateral mastectomy and immediate expander-implant reconstruction nipple-sparing mastectomy versus skin-sparing mastectomy. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 43(2), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-018-1217-8 (2019).

D’Agostino, R. B. Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat. Med. 17(19), 2265–2281. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19%3c2265::aid-sim918%3e3.0.co;2-b (1998).

Cano, S. J., Klassen, A. F., Scott, A. M., Cordeiro, P. G. & Pusic, A. L. The BREAST-Q: Further validation in independent clinical samples. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129(2), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aec6b (2012).

Pusic, A. L. et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124(2), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807 (2009).

Seth, I., Seth, N., Bulloch, G., Rozen, W. M. & Hunter-Smith, D. J. Systematic review of breast-Q: A tool to evaluate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Breast Cancer 13, 711–724. https://doi.org/10.2147/bctt.S256393 (2021).

Brehaut, J. C. et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med. Decis. Mak. 23(4), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x03256005 (2003).

Cai, L. & Momeni, A. The impact of reconstructive modality and postoperative complications on decision regret and patient-reported outcomes following breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 46(2), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-021-02660-2 (2022).

Zhong, T. et al. Decision regret following breast reconstruction: The role of self-efficacy and satisfaction with information in the preoperative period. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 132(5), 724e–734e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a3bf5d (2013).

Sheehan, J., Sherman, K. A., Lam, T. & Boyages, J. Regret associated with the decision for breast reconstruction: The association of negative body image, distress and surgery characteristics with decision regret. Psychol. Health 23(2), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320601124899 (2008).

Voineskos, S. H., Klassen, A. F., Cano, S. J., Pusic, A. L. & Gibbons, C. J. Giving meaning to differences in BREAST-Q scores: Minimal important difference for breast reconstruction patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 145(1), 11e–20e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000006317 (2020).

Romanoff, A. et al. A comparison of patient-reported outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy and conventional mastectomy with reconstruction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25(10), 2909–2916. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6585-4 (2018).

Funding

Supported by grants from the Hubei Province Medical Youth Top Talent Project (EWT [2023] 65, Oncology), the Hubei Cancer Hospital Biomedical Center Research Project (Grant Numbers 2022SWZX03 and 2022SWZX09), the Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation of Innovation and Development Joint Fund Projects (Grant Number 2024AFD454) and the Hubei Chen Xiaoping Science and Technology Development Foundation (Grant Number CXPJJH123001-2320).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuhang Song contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, and Writing—original draft. Lingzi Wang was responsible for Data curation, Investigation, and Writing—review & editing. Wenqin Huang participated in Software, Validation, and Visualization. Senyang Guo contributed to Resources, Project administration. Xinhong Wu and Hongmei Zheng supervised the study and were involved in Funding acquisition, Supervision, and Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Y., Wang, L., Huang, W. et al. Comparison of nipple sparing and skin sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction based on patient reported outcomes. Sci Rep 15, 14989 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99834-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99834-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Psychiatric Considerations in Breast Cancer: an Integrative Review

Current Psychiatry Reports (2025)