Abstract

To investigate the mediating role of family care and self-efficacy between stigma and social alienation among colorectal cancer survivors. In a cross-sectional study, 357 colorectal cancer survivors were recruited in northern China. The General Alienation Scale, Social Impact Scale, Family Care Index Questionnaire, and General Self-efficacy Scale were used to conduct the survey, and the mediation model was constructed and tested. Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 25.0 software. Colorectal cancer survivors’ social alienation was positively correlated with stigma (r = .481), and negatively correlated with family care (r = -.514)、and self-efficacy (r = -.506). Family care and self-efficacy both partially mediated the relationship between stigma and social alienation, with mediator effect values of 0.10 and 0.12, and the two consecutive paths were chained together, with a mediator effect of 0.02. Colorectal cancer survivors’ stigma and social alienation are at a moderate level, and the stigma can directly and indirectly contribute to social alienation through family care and self-efficacy. Healthcare professionals can take targeted interventions to improve patients’ family care and self-efficacy and reduce their social alienation, to promote the social integration of colorectal cancer survivors and improve the quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global Cancer Statistics for 2020 show that there were 1.9 million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) and 935,000 deaths globally, which were in the third and second place, respectively, of all malignant tumors1. In China, colorectal ranked second in terms of incidence, but fourth in terms of mortality, which had become a serious threat to human health2. Cancer survivors are patients who have completed primary tumor treatment and are in the ongoing survival stage, including patients who have fully recovered and are expected to recover3. It has been found that cancer survivors are often accompanied by heavier psychosocial burden during their long-term survival, and that patients are prone to feel lonely in interpersonal interactions, and to develop social alienation behaviors such as avoidance or rejection4. Social alienation is defined as an individual’s lack of social belonging and contact with others, low socialization, lack of fulfillment, and quality relationships5. This state of social alienation not only affects the physical, mental health and quality of life, but also increases the pressure on the families as well as the society. In addition, social alienation is one of the main risk factors for suicidal behavior6. As cancer incidence continues to rise, the social alienation of CRC survivors is in dire need of attention and targeted improvement. Studies have shown that gender and residential situation can have an effect on social alienation7,8,9. We have yet to determine whether these variables can influence CRC patients’ social alienation. In addition, cancer survivors’ disease stage and treatment modalities, such as radiotherapy and stoma status, may also influence their social alienation8,10,11. Therefore, we formulated the hypothesis.

Hypothesis (i)

CRC survivors’ sociodemographic information, namely, gender (H.i.a.), residential environment (H.i.b.), tumor status (H.i.c.), radiotherapy (H.i.d.), and stoma status (H.i.e.), have an effect on social alienation.

Stigma is defined as a negative emotional experience that occurs in individuals who have been treated unequally by society due to the physical effects of the disease12. Stigma is the main factor influencing the social alienation of CRC patients. CRC patients are often reluctant to go out exclude themselves from social interaction and stay away from social groups because of the stigma brought about by the disease itself, resulting in varying degrees of alienation from the people around them and society13. Accordingly, this study formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (ii)

Stigma can directly predict social alienation.

Family care can give more help, encouragement, and support and provide a certain environment for the healthy development of the patient’s physical, mental, and social aspects. It has been found that stigma can indirectly affect patients’ social situation through the mediating role of family care14. Stigma may be a major barrier to social adjustment, undermine the effectiveness of family care and affect their social behavior. Family care is an important protective factor for social alienation, and higher levels of family care are associated with weaker social alienation15,16. Self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s demonstrated confidence in his or her ability to perform a behavior in a specific situation17. Self-efficacy may contribute to cognitive and behavioral change18. Stigma may lead to reduced self-efficacy in CRC patients19. At the same time, higher self-efficacy is strongly associated with lower social alienation20. If CRC survivors can feel their self-efficacy and support from their families, they may be able to reduce their stigma, which in turn reduces their social alienation.

The process theory of stress states that psychological stress is a multifactorial process from the stressor (life event) to the stress response. In the process model, psychological stress is a multifactorial process in which an individual is ultimately manifested in a physiological and psychological response through the mediation of intermediary factors (e.g., cognition, coping, social support, personality traits)21. Stigma is an important life event of the patient’s stress response and a stressor of the stress process. Social alienation is a psychological response to long-term stress and inability to cope, which is one of the stress responses of the stress process in cancer patients. Family care and self-efficacy act as intermediary factors in the stress response process, playing an important role as mediators between the stressor (stigma) and the stress response (social alienation). Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis (iii)

Family care mediates the relationship between stigma and social alienation.

Hypothesis (iv)

Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between stigma and social alienation.

Previous study had shown that there was a significant positive relationship between family care and self-efficacy that higher levels of family care could make patients feel understood and supported, improve self-efficacy, and thus reduce social alienation22. As a result, this study formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (v)

Family care and self-efficacy have a chain mediating effect between stigma and social alienation.

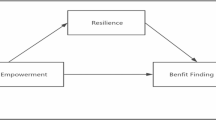

Figure 1A showed a conceptual model depicting the relationships between stigma, family care, self-efficacy, and social alienation.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study aimed to explore the mediation effects of family care and self-efficacy between stigma and social alienation. Participants were recruited at two tertiary hospitals in Jinzhou, China, from March to June 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed as CRC through pathology or cytology with completion of initial clinical treatment such as surgery or radiation or chemotherapy, (2) aged ≥ 18 years, (3) pathologic staging of stage I to III, (4) clear awareness and unobstructed language communication, and agree to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria: (1) serious and uncontrolled organic lesions or infections, (2) patients with mental illness or family history, (3) combined with other malignant tumors. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee. Oral informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the survey. The reporting of findings was informed by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

The minimum required sample size was calculated using G*Power to be 77 participants considering a 95% confidence interval, power of 80%, and effect size = 0.15. A total of 388 CRC survivors were recruited in this study, and 357 valid questionnaires were finally obtained after excluding invalid questionnaires such as missing information. Demographic information of the participants was showed in Table 1.

Measures

Demographic information

The demographic section was designed by the research team to collect the general characteristics of CRC survivors, including gender, age, educational level, occupation, marital status, monthly income, living alone or not, tumor staging, having radiotherapy or not, having stoma or not, having chronic disease or not.

Social alienation

Chinese scholars Wu et al. translated and revised the English version of the General Alienation Scale (GAS), which has 15 items in four dimensions (the sense of self-alienation, the sense of social alienation, powerlessness, and meaninglessness)23. The scale is based on a 4-point Likert scale with a total score ranging from 15 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher sense of social alienation among the participants. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.811.

Stigma

The Social Influence Scale (SIS) developed by File et al. was used to measure stigma in patients with chronic diseases such as cancer24. Pan and other scholars translated it into Chinese in 200725. The Chinese version of the SIS contains 4 dimensions (social rejection, financial insecurity, internalized shame, and social isolation) with a total of 24 items. The scale is rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with a total score of 24 to 96. The higher the score, the greater the perceived social influence, and the more serious the stigma. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.813.

Family care

The family APGAR index (APGAR) developed by Smilkstein was used to measure the family care of the participants26. This study used a Chinese version of the scale translated by Fan and other scholars, which is widely used in China to assess family functioning in a variety of patient populations27. It’s a five-item (adaptation, partnership, growth, affection, and resolution) scale with a three-point option for each item ranging from 0 (hardly ever) to 2 (almost always). The total score is the sum of all 5 items ranging from 0 to 10. Higher scores indicate better family functioning by the patient. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.816.

Self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) was developed by Schwarzer et al.28, and the Chinese version translated and revised by Wang et al.29 was used in this study. The Chinese version of the scale consists of 10 items, using a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 to 4 from “completely incorrect” to “completely correct”. The scores for this part ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores representing greater self-efficacy of the testers. The Cronbach’s alpha in our study was 0.802.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. All data passed the normality test. The measurement data was described using the mean and standard deviation (SD). Descriptive analyses, independent sample t-tests, and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to compare demographic information and differences in scores. Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine the correlation between stigma, family care, self-efficacy, and social alienation. All entries were examined for common method bias using the Harman one-way test. After multicollinearity test was used to prove that there was no serious covariance problem, multiple linear regression analysis was used to investigate the influencing factors of social alienation among CRC survivors. The mediation effects of family care and self-efficacy between stigma and social alienation were analyzed using Model 6 in the PROCESS 3.5 macro with a bootstrapped confidence interval (5000 bootstrap samples). p < .05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and social alienation symptoms

A total of 357 CRC survivors were recruited in our study. The comparison of total social alienation scores among 357 CRC survivors revealed statistically significant differences based on gender, t (355) = 2.562, p < .05; living alone status, t (355) = 2.228, p < .05; tumor stage, F (2, 354) = 3.127, p < .05; radiotherapy status, t (355) = 2.564, p < .05; and stoma status, t (355) = 2.714, p < .01. The hypothesis (i) was confirmed. The detailed information was shown in Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among all the variables

Pearson correlation analysis showed that CRC survivors’ stigma score was positively correlated with social alienation score (r = .481, p < .05) and negatively correlated with family care score (r = -.313, p < .05) and self-efficacy score (r = -.456, p < .05). Family care score was negatively correlated with social alienation score (r = -.514, p < .05) and positively correlated with self-efficacy score (r = .282, p < .05). The self-efficacy score was negatively correlated with the social alienation score (r = -.506, p < .05) (Table 3).

Mediation model analyses

Common method bias was examined according to Harman’s one-way test. Since the data were obtained from the participants’ self-reports, unrotated exploratory factor analyses were used for all the questions in the four study variables: stigma, social alienation, family care, and self-efficacy. The results showed that a total of 16 factors were analyzed with an eigenvalue > 1, and the maximum factor variance explained was 17.364%, which was < 40% of the critical criterion, indicating that there was no serious common method bias in this study.

Gender (male = 1, female = 2), living alone or not (yes = 1, no = 2), tumor stage (stage I = 1, stage II = 2, stage III = 3), having radiotherapy or not (yes = 1, no = 2), having stoma or not (yes = 1, no = 2) were used as the control variables, and all variables were standardized. The chain mediation model of stigma as an independent variable, social alienation as a dependent variable, and family care and self-efficacy as mediator variables were empirically investigated.

The results of regression analysis showed that the direct effect of stigma on social alienation was significant (β = 0.221, p < .01), and hypothesis (ii) was confirmed. The stigma had a significant negative effect on family care and self-efficacy (β values of -0.302 and − 0.411, p < .05). Family care had a significant positive effect on self-efficacy (β = 0.158, p < .01), and a significant negative effect on social alienation (β = -0.333, p < .01). Self-efficacy had a significant negative effect on social alienation (β = -0.303, p < .01). (Table 4; Fig. 1B).

The mediation effect analysis indicated a significant total indirect effect through three paths. Specifically, family care mediated the relationship between stigma and social alienation, with a 95% bootstrap CI of [0.06, 0.15] excluding zero, supporting hypothesis (iii). Self-efficacy significantly mediated the stigma-social alienation relationship (95% bootstrap CI = [0.08, 0.18]), supporting hypothesis (iv). Additionally, the chain mediation effect of family care and self-efficacy was significant (95% bootstrap CI = [0.01, 0.03]), confirming hypothesis (v). The mediation effect was significant with a total mediation effect of 52.17% (Table 5).

Discussion

This study investigated the current status of social alienation among CRC survivors, and explored the mediation effect of family care and self-efficacy between stigma and social alienation via a chain mediation model. Consistent with our hypotheses, our findings suggested that stigma, family care, and self-efficacy were all significantly associated with social alienation, but the effects of these factors were different.

The results of this study showed that the total score of social alienation of CRC survivors was 37.84 ± 5.38, which was at a medium-high level compared with the full score of 60. This result was consistent with the study of Guo et al., which suggested that social alienation of CRC patients should be paid attention to30. In this study, female patients, living alone, receiving radiotherapy, highly staged and stoma patients have higher levels of social alienation. Cancer diagnosis and treatment disrupt patient’s normal lives, weakening personal achievement expectations and predisposing to social alienation31. Female patients can be more sensitive to bodily functions and appearance, especially for colostomy patients. Bowel movement changes and stoma bags cause them more social alienation32.

Our results supported the hypothesis that stigma positively correlated with the social alienation of CRC survivors. This suggested that the higher the patient’s stigma, the more severe their social alienation. The result was generally consistent with previous study33. CRC survivors faced a variety of challenges throughout their lifetimes. Chemotherapy and stoma can cause appearance changes, bowel dysfunction, which sensitized the patient’s social relationships and made them reluctant to socialize and withdraw from their social groups13,34. Stigma affected the patient’s communication and socialization with others, resulting in varying degrees of social alienation35. Early assessment of patients’ level of stigma could help healthcare professionals implement individualized interventions to reduce the level of social alienation and help patients improve their social integration and quality of life.

Results of the mediation effect suggested that family care partially mediated the relationship between stigma and social alienation. It is suggested that lower stigma is a prerequisite for reducing patients’ social alienation, and family care becomes an important safeguard in this process. Stigma makes the patients become inferior, isolated, and unwilling to communicate with family, which damages the family function. Patients with low levels of family care may receive less material or moral encouragement. They may lack the confidence to face their illness, develop negative coping strategies, and ultimately develop social alienation36. Social alienation scores were significantly negatively correlated with family care scores, so increasing support from family members could reduce social alienation. Healthcare workers should assist patients in recognizing effective family care and provide appropriate medical resources to alleviate social alienation. Family members should actively engage with patients, monitor their psychological and behavioral changes, and support them in coping with disease-related pain and stress37.

Our findings found that self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between stigma and social alienation. Stigma had been recognized as an important barrier to recovery, leading to diminished self-efficacy, social withdrawal, and alienating behaviors38. Stigma served as a prerequisite for the development of social alienation among patients, with the self-efficacy playing a crucial role as a protective factor. A high level of self-efficacy in CRC patients could effectively cope with stress and frustration, which was more conducive to patients’ integration into society and contributed to the reduction the social alienation. Therefore, it was not only necessary to strengthen the education of patients’ knowledge of the disease, but also to promote the enhancement of self-efficacy through the forms of encouragement and guidance, to enable the CRC patients to better integrate into the society.

The results of our study presented a third path of the indirect effect of stigma on social alienation through the chained mediation model that stigma could have an indirect effect on social alienation in the presence of family care and self-efficacy. Consistent with the results of this study, Zhang et al.39 also showed that patients’ family care had a direct positive effect on self-efficacy that patients with high family care had higher self-efficacy and promoted individuals to adopt more positive coping styles. With the support of the family, patients could receive more care and attention. Economic, informational, and emotional family support enhances patients’ self-efficacy, fostering social interactions and alleviating social alienation40. Caregivers can enhance CRC patients’ self-efficacy and social participation by fostering family interactions and providing supportive care, thereby reducing social alienation.

For the special population of CRC survivors, adapting to their disease and overcoming the difficulties brought on by it is preferable to curing it. Based on these results, new ideas can be provided for the care of CRC survivors. First, clinical workers should give focused attention to CRC survivors with high levels of stigma, low family care, and low self-efficacy. Secondly, diversified care models have been developed and quality care concepts have been implemented to enhance patients’ family care and self-efficacy, which have significantly contributed to the reduction of patients’ social alienation.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study was conducted only locally in Jinzhou City, and the reproducibility of the results is unclear. To ensure the generalizability of the results, subsequent multi-center and multi-regional studies are needed. Second, this study was a cross-sectional study, which could not determine the causal relationship between variables related to social alienation, and longitudinal studies can be conducted next based on the framework to provide a scientific basis for the clinical development of interventions. Finally, it is recommended to expand the sample size for model validation.

Conclusion

CRC survivors’ stigma and social alienation were at a moderate level, and the stigma can directly affect social alienation, and indirectly affect social alienation through family care and self-efficacy.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Zheng, R. S. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 46 (3), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240119-00035 (2024).

Dirven, L., van de Poll-Franse, L. V., Aaronson, N. K. & Reijneveld, J. C. Controversies in defining cancer survivorship. Lancet Oncol. 16 (6), 610–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70236-6 (2015).

Dewar, E. O., Ahn, C., Eraj, S., Mahal, B. A. & Sanford, N. N. Psychological distress and cognition among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in the USA. J. Cancer Surviv. 15 (5), 776–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00969-6 (2021).

Nicholson, N. R. Jr Social isolation in older adults: An evolutionary concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 65 (6), 1342–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04959.x (2009).

Calati, R. et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 245, 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022 (2019).

Kroenke, C. H. et al. Prediagnosis social support, social integration, living status, and colorectal cancer mortality in postmenopausal women from the women’s health initiative. Cancer 126 (8), 1766–1775. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32710 (2020).

Wang, C., Qiu, X., Yang, X., Mao, J. & Li, Q. Factors influencing social isolation among Cancer patients: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 12 (10). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101042 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Suicidal risk among Chinese parents of autistic children and its association with perceived discrimination, affiliate stigma and social alienation. BMC Psychiatry. 24 (1), 784. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06252-7 (2024).

He, C. et al. Characteristics and influencing factors of social isolation in patients with breast cancer: A latent profile analysis. Support Care Cancer. 31 (6), 363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07798-0 (2023).

Li, M. J. et al. Research progress on social alienation in colorectal cancer patients with enterostomy. Chin. J. Mod. Nurs. 30 (6), 815–820. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20230608-02293 (2024).

Ernst, J. et al. Stigmatization in employed patients with breast, intestinal, prostate and lung Cancer. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 67 (7), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-110138 (2017).

Lim, C. Y. S. et al. Colorectal cancer survivorship: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 30 (4), e13421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13421 (2021).

Zhang, L., Yu, R., Zheng, Q. H. & Yang, Y. Study on relationship model between stigma,family function of breast cancer patients and their quality of life. Chin. Nurs. Res. 31 (11), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2017.11.014 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. The influence of social alienation on maintenance Hemodialysis patients’ coping styles: Chain mediating effects of family resilience and caregiver burden. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1105334. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1105334 (2023).

Xu, Y. J. et al. Social alienation and its influencing factors among patients undergoing maintenance Hemodialysis. J. Nurs. Sci. 39 (07), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2024.07.086 (2024).

Oki, M. & Tadaka, E. Development of a social contact self-efficacy scale for ‘third agers’ in Japan. PLoS One. 16 (6), e0253652. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253652 (2021).

Wang, D. F. et al. Social support and depressive symptoms: Exploring stigma and self-efficacy in a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry. 22 (1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03740-6 (2022).

Jin, Y., Ma, H. & Jiménez-Herrera, M. Self-disgust and stigma both mediate the relationship between stoma acceptance and stoma care self-efficacy. J. Adv. Nurs. 76 (10), 2547–2558. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14457 (2020).

Bevilacqua, G. et al. General self-efficacy, not musculoskeletal health, was associated with social isolation and loneliness in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Hertfordshire cohort study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36 (1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02676-5 (2024).

Lei, T. Path Analysis from Symptom Burden To Demoralization in Elderly Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy [D] (Fuzhou; Fujian Medical University, 2021).

Mei, Y. X. et al. Family function, self-efficacy, care hours per day, closeness and benefit finding among stroke caregivers in China: A moderated mediation model. J. Clin. Nurs. 32 (3–4), 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16290 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Reliability and validity of the generalized social of alienation scale among the elderly. J. Chengdu Med. Coll. 10 (06), 751–754. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-2257.2015.06.031 (2015).

Fife, B. L. & Wright, E. R. The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J. Health Soc. Behav. 41 (1), 50–67 (2000).

Pan, A. W., Chung, L., Fife, B. L. & Hsiung, P. C. Evaluation of the psychometrics of the social impact scale: A measure of stigmatization. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 30 (3), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32829fb3db (2007).

Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C. & Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 15 (2), 303–311 (1982).

Zhang, H. et al. Family functioning and health-related quality of life of inpatients with coronary heart disease: A cross-sectional study in Lanzhou City, China. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22 (1), 397. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02844-x (2022).

Schwarzer, R., Baessler, J., Kwiatek, P. J., Schroder, K. E. E. & Zhang, J. The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Appl. Psychol. 46 (1), 69–88 (1997).

Wang, C., Hu, Z. & Liu, Y. Evidences for reliability and validity of the Chinese version of general Self-Efficacy scale. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 7 (1), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-6020.2001.01.007 (2001).

Guo, L. P., Huo, Y. Q. & Fu, Q. H. Current situation of social alienation and its influencing factors among young and middle-aged patients with colorectal cancer. Chin. J. Mod. Nurs. 29 (23), 3189–3193. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20230301-00769 (2023).

Fox, R. S. et al. Social isolation and social connectedness among young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. Cancer 129 (19), 2946–2965. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34934 (2023).

Hueso-Montoro, C. et al. Experiences and coping with the altered body image in digestive stoma patients. Rev. Lat Am. Enfermagem. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1276.2840 (2016). ,24(e2840.

Drenkard, C. et al. Depression, stigma and social isolation: The psychosocial trifecta of primary chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a cross-sectional and path analysis. Lupus Sci. Med. 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1136/lupus-2022-000697 (2022).

Yıldız, K. & Koç, Z. Stigmatization, discrimination and illness perception among oncology patients: A cross-sectional and correlational study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102000 (2021). ,54(102000.

Prizeman, K., Weinstein, N. & McCabe, C. Effects of mental health stigma on loneliness, social isolation, and relationships in young people with depression symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1), 527. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04991-7 (2023).

McInally, W., Gray-Brunton, C., Chouliara, Z. & Kyle, R. G. Life interrupted: Experiences of adolescents, young adults and their family living with malignant melanoma. J. Adv. Nurs. 77 (9), 3867–3879. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14959 (2021).

Lou, Y. et al. Unmet supportive care needs and associated factors: A Cross-sectional survey of Chinese Cancer survivors. J. Cancer Educ. 36 (6), 1219–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01752-y (2021).

Yan, M. H., Fan, Y., Chen, M. & Zhang, J. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the association between perceived stigma and psychosocial adjustment: A cross-sectional study among nasopharyngeal cancer survivors. Psychooncology 31 (5), 806–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5865 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Mediation effect of Self-Efficacy and Self-Management ability between family care and quality of life in elderly patients with coronary heart disease from Rnral areas. Nurs. J. Chin. People’s Lib. Army. 38 (5), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2021.05.004 (2021).

Guerra, C., Farkas, C. & Moncada, L. Depression, anxiety and PTSD in sexually abused adolescents: Association with self-efficacy, coping and family support. Child. Abuse Negl. 76, 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.013 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their families for participating in the study.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Study conception and design: X L, S W and D W. Date collection and analysis: X L and S W. Drafting of the article: X L. Critical revision of the article: X L, S W and D W. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approval by the Ethics Committee of the Jinzhou Medical University (JZMULL2025019).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Wen, S. & Wu, D. The mediating roles of family care and self-efficacy between stigma and social alienation among colorectal cancer survivors. Sci Rep 15, 15312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99852-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99852-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Breaking the invisible cage: social isolation and coping strategies among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2025)