Abstract

Negative symptoms and social function have been known to predict work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. Recent studies report that specific subdomains of these predictors were particularly important in prediction. The aims of this study were (1) to determine which subdomains of negative symptoms and social function were the most important predictors of work outcomes among patients with schizophrenia, and (2) to use these factors to produce charts to demonstrate the estimated probabilities of workable hours. Data were obtained from 293 patients with schizophrenia. Four separate logistic regression analyses were conducted using psychiatric symptoms, intellectual ability, and social function as independent variables to predict work hours (0, 10, 20, or 30 h per week). The Experiential deficit domain of negative symptoms, comprising of volitional, social, and hedonic deficits, and the Independence-Performance domain including self-care and daily-living skills were significant in most regression models. Charts illustrating the probabilities of the ability to work were produced based on these two predictors. Our study identified specific domains of negative symptoms and social function were relevant to work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. The charts illustrating the probabilities of workable hours provide objective information about the capacity to work among patients with schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a major psychiatric illness that poses a large financial burden to society, yielding direct costs (e.g., medical treatments or social services) as well as indirect costs (e.g., premature death by suicide and productivity loss due to poor vocational functioning)1. Specifically, the indirect costs of schizophrenia are substantial in Japan because of higher rates and longer periods of hospitalization2. According to governmental survey in 2022, it is estimated that employed mental disorders account for less than 0.2% of the entire working population in Japan3. The figure may be even lower by narrowing down the target to schizophrenia only.

In addition to the socio-economic issues, a lack of work experience may adversely affect patients’ subjective quality of life by decreasing their self-efficacy or self-esteem4,5. Therefore, it seems necessary to provide objective feedback regarding the ability to work among these individuals in order to reduce disease-related costs and to promote their well-being and functional recovery.

Factors affecting work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia were shown to be negative symptoms, cognition, intellectual ability, functional capacity, and social function6,7. Using several contributing factors including negative symptoms and social function, a previous study has presented prediction models for probabilities of workable hours (e.g., 0, 10, or 20 h per week)8.

The structure of negative symptoms (e.g., blunted affect, alogia, avolition, asociality, and anhedonia) has been continuously discussed9,10. It has been suggested that negative symptoms can be categorized into 2 domains, i.e., expressive deficits and experiential deficits (for review, see Correll & Schooler, 202011). The former domain refers to poor emotional expressivity and poverty of speech, whereas the latter domain includes avolition, withdrawal, and anhedonia. These two domains (hereafter denoted in upper case: Expressive deficits and Experiential deficits) are universally detected in schizophrenia irrespective of regional or cultural differences12,13.

Social function, another potential predictor of work outcome, can also be characterized by two domains14. One of them covers prosocial or recreational activities, including interpersonal relationships and recreational activities, whereas the other consists of abilities to live independently such as self-care, daily-living skills, and vocational functioning14.

Differential degrees of contribution to work status may present within the domains of both negative symptoms and social function in patients with schizophrenia. The Experiential deficits in negative symptoms has a greater impact on work outcomes than the Expressive deficits15,16. Similarly, independent living ability, a component of social function, is assumed to have greater influence on work outcomes than prosocial or recreational activities probably because everyday living behaviour well reflects cognitive ability in patients with schizophrenia17. Thus, it seems necessary to examine the role of each domain of negative symptoms and social function in predicting work status in patients with schizophrenia.

The clinical application of the prediction models should also be considered. By using significant predictors in the models, it is possible to estimate the probability that an individual can work for a certain amount of time8. A feasible presentation of such results would be beneficial for clinicians and patients. For example, “at-a-glance charts” of the estimated probabilities for workable hours per week could be used objective feedback about work capacity in real world settings.

The aims of this study were (1) to determine which subdomains of negative symptoms and social function were the most prominent predictor in predicting work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia, and (2) to produce charts presenting the estimated probabilities of workable hours based on those factors.

Methods

Participants

Data were obtained from 293 patients meeting DSM-4 or DSM-5 criteria for schizophrenia18. They were treated at the Department of Psychiatry, Osaka University Hospital or National Centre Hospital, National Centre of Neurology and Psychiatry. The details of their demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Osaka University and the Ethical Committee of National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessments

Psychotic symptoms

Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS)19. To replicate the two factor structure of negative symptoms, i.e. Expressive deficits and Experiential deficits, in the Asian sample12,13, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted specifying the Expressive deficits factor (N1, Blunted Affect; N3, Poor Rapport; N6, Lack of Spontaneity; G7, Motor Retardation) and the Experiential deficits factor (N2, Emotional Withdrawal; N4, Passive Social Withdrawal; G16, Active Social Avoidance). The details of the CFA are summarized in the supplementary material, sTable 2.

Intellectual ability

Intellectual ability was evaluated by current IQ, premorbid IQ, and their discrepancy. The former two were estimated by using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition20 and the Japanese version of the Adult Reading Test21, respectively. IQ discrepancy was calculated by subtracting premorbid IQ from current IQ22.

Social function

Social function was evaluated by using the Japanese version of the modified Social Functioning Scale (SFS) designed for the MATRICS Standardization and Psychometric Study23,24. The details of the modified version of the SFS were explained in our previous study8, and the validity of the Japanese version has been reported in previous studies5,25. The scale consists of 7 domains: Withdrawal, Social Engagement, Interpersonal Communication, Independence-Performance, Independence-Competence, Recreation, and Employment/Occupation, as in the original version of the SFS26,27. To avoid overlap with dependent variable (i.e. work hours a week), the adjusted total score was calculated excluding the Employment/Occupation subscale score from the total score. This adjustment increased the validity of the prediction.

Work

Total work hours per week in the past 3 months were used as work status variable which was obtained from the Social Activity Assessment (SAA)28. This scale evaluates Work for pay, Work at Home, and Student work. If a participant experienced multiple types of work, the work hours were summed. Although both the SFS and the SAA could be administered in a self-report manner, most data of the current study was collected by interview to patients.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression analysis for prediction models

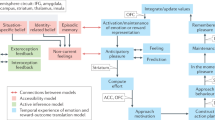

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to construct predicting models. Nonlinear modelling was used as it was assumed that probability (e.g. the possibility of working more than 20 h per week is approximately 53%) was more suitable for presenting in charts, and also for verbal feedback, rather than exact number of hours (e.g. 20.5 h per week). The significance of nonlinear modelling for clinical settings is explained in our previous study8. Four separate regression analyses were conducted according to different dependent variables. The outline is summarized in the upper part of Fig. 1. Dependent variables were stratified by a criterion of the 0, 10, 20, or 30 h per week noted as 0-, 10-, 20-, or 30-h criterion, respectively. Patients were classified into either the above (= 1) or the below (= 0) criterion depending on their actual number of work hours. The independent variables were demographic background (education), intellectual ability (current IQ, premorbid IQ, and IQ discrepancy), negative symptoms (factor scores on the Expressive deficits factor and the Experiential deficits factor obtained from CFA) and social function (SFS adjusted total scores and subdomain scores). All the dependent variables were standardized. A forward selection method with a likelihood ratio criterion was applied. Model fits and coefficients were tested by the likelihood test and the Wald test, respectively. The predictive accuracy was estimated by the sum of the ratios correctly classified (i.e., patient’s observed outcome = 1[0] and the estimated probability ≥ 0.5 [< 0.5]).

Charts of estimated probabilities of work hours

Using significant variables in predicting models, logistic regression analyses were newly performed to produce charts for each criterion. The outline is presented in the lower part of Fig. 1. The independent variables were not standardized in this model and the subscale scores of symptom factors, rather than factor scores, were used so that the charts presented actual assessment scores. The results of regression analyses for charts are presented in e supplementary material sTable3. The estimated probabilities (p) at each criterion were calculated using logits (log[p/(1-p)]) obtained from regression equations (see supplements for details, sFigure 1). To enhance clinical utility, the charts were zoned according to the probabilities as follows: Grade A, p ≥ 0.8[80%]; Grade B, p ≥ 0.6[60%]; Grade C, p ≥ 0.4[40%]; Grade D, p ≥ 0.2[20%]; Grade E, p < 0.2[less than 20%]).

Results

Logistic regression analysis

The results are summarized in Table 2. The Independence-Performance was significant in all the regression models. The Experiential deficits was also significant in all the models except the model with the 0 h per week criterion.

Charts

Based on the results from logistic regression analyses, the Independence-Performance and Experiential deficits were used as entries to the charts (Fig. 2b–d), with the exception of the 0-h criterion (Fig. 2a). A single entry was appropriate for the 0-h criterion as only the Independence-Performance was significant. An example of reference for a probability (%) is depicted in Fig. 2e. The five zones (A-E) noted in the Methods section are shown in different colours. With respect to the criterion of longer working hours, the Grade A zones (p ≥ 0.8[80%]) were less noticeable and eventually disappeared at the 30-h criterion (Fig. 2d).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine which subdomains of negative symptoms and social function predict work status, as represented by working hours per week, among patients with schizophrenia. Logistic regression analyses revealed significant contributions of the Experiential deficits on negative symptoms and the Independence-Performance on social function to work outcomes. Using these factors, charts were produced to illustrate the probabilities of working for a certain number of hours a week.

The Independence-Performance on the SFS may be a highly important measure of functional recovery in patients with schizophrenia and other mental disorders. First, the domain assesses mostly daily living skills, including self-care and household choirs, which are critical skills for independent living. Therefore, the demographic (e.g., generations and sex) or cultural variations are relatively minor compared with other domains of the SFS (e.g., Recreation). Second, most daily-living acts are simple and customary performed, and therefore, they are easily recorded by handy device such as a smartphone. An introduction of digital device could enhance reliability of the prediction for work outcome. In addition, the aggregation of such information could form the basis of digital phenotype, that may support individual functional recovery. Third, performance on daily living skills is strongly associated with cognition in patients with schizophrenia17. This suggests that the assessment of the Independence-Performance could provide information about cognitive function as well as work outcomes. Possibly because of this strength, this domain has been chosen for the short version of the SFS29.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to apply prediction models to produce charts for the probability of workable hours per week in patients with schizophrenia. This is meaningful as the charts are clinical application of the theoretical models in prediction. The charts may help clinicians provide their patients and caregivers with feasible feedback regarding attainable occupational outcomes. Practical feedback based on the charts could contribute to bridging an evidence-practice gap that has been addressed in clinical settings30.

The charts could also be used as a self-management tool in patents with schizophrenia. It is known that they are generally reluctant to perform goal-directed activities due to the disturbance in conceiving anticipatory pleasures (i.e., expectations for rewards related to future activities)31. In fact, not only intrinsic motivation, but extrinsic motivation (e.g. seeking reward) is important in work outcome in patients with schizophrenia32. A visual presentation of the likelihood of successfully doing an appropriate amount of work may increase motivation in patients who are capable but discouraged to work. On the other hand, some patients with schizophrenia often overestimate their ability to work, particularly those who have limited experience in working33,34. Likewise, some patients tend to conceive jumping-to-conclusions bias, i.e. impetuous behaviour without concrete evidence35. In those cases, the charts may help patients assess their work capacity adjusting their insights.

Limitations

Some limitation should be noted. First, we did not include the WHO initiative measurement such as WHODAS 2.0. in the analyses. This may limit the comparability and generalizability of the results. Second, the Grade A zone, where the probability exceeds 0.8, disappears at higher criterion (i.e. 30 h/week, Fig. 2d). This finding suggests that the estimation might be difficult for patients with milder symptoms, and therefore who wish to work for longer time. In fact, a previous study36 reported that the association between experiential deficits symptoms and vocational functioning (e.g., ability to stay on tasks or complete tasks) was weak in patients with mild experiential deficit symptoms, suggesting the difficulty of prediction for patients with minor symptoms. Third, it is possible that other intermediating factors (e.g. working environment, availability of social support or rehabilitation program, or stigma) might interfere with predicting work outcomes particularly in patients with less severe symptoms and/or a better ability to live independently. The prediction models and charts in the current study should be extended to increase utility in relatively high-functioning patients. Further studies that incorporate these issues are warranted.

Conclusions

The experiential negative symptoms including volitional and hedonic deficits and the independent-living ability covering basic daily-living skills are major determinants of work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. The charts proposed in this study would provide objective information to clinicians and patients regarding the capacity to work among individuals with schizophrenia.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the senior author, R. H. (ryotahashimoto55@ncnp.go.jp).

References

Rossler, W., Salize, H. J., van Os, J. & Riecher-Rossler, A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15(4), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.009 (2005).

Nakamura, Y. & Mahlich, J. Productivity and deadweight losses due to relapses of schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 13, 1341–1348. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S138033 (2017).

Ministry of Health, L.a.W. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Annual reports in 2022. (2022).

McGurk, S. R. & Mueser, K. T. Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: A review and heuristic model. Schizophr. Res. 70(2–3), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.009S0920996404000398[pii] (2004).

Fujino, H. et al. Predicting employment status and subjective quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 3, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2015.10.005 (2016).

Bowie, C. R., Reichenberg, A., Patterson, T. L., Heaton, R. K. & Harvey, P. D. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatry 163(3), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418 (2006).

Sumiyoshi, C. et al. Factors predicting work outcome in Japanese patients with schizophrenia: Role of multiple functioning levels. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2(3), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2015.07.003 (2015).

Sumiyoshi, C. et al. Predicting work outcome in patients with schizophrenia: Influence of IQ decline. Schizophr. Res. 201, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.042 (2018).

Messinger, J. W. et al. Avolition and expressive deficits capture negative symptom phenomenology: Implications for DSM-5 and schizophrenia research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31(1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.002 (2011).

Kirkpatrick, B., Fenton, W. S., Carpenter, W. T. Jr. & Marder, S. R. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 32(2), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj053 (2006).

Correll, C. U. & Schooler, N. R. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 519–534. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S225643 (2020).

Khan, A. et al. Negative symptom dimensions of the positive and negative syndrome scale across geographical regions: Implications for social, linguistic, and cultural consistency. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 14(11–12), 30–40 (2017).

Jang, S. K. et al. A two-factor model better explains heterogeneity in negative symptoms: Evidence from the positive and negative syndrome scale. Front. Psychol. 7, 707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00707 (2016).

Okada, H., Hirano, D. & Taniguchi, T. Single versus dual pathways to functional outcomes in schizophrenia: Role of negative symptoms and cognitive function. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 23, 100191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2020.100191 (2021).

Llerena, K., Reddy, L. F. & Kern, R. S. The role of experiential and expressive negative symptoms on job obtainment and work outcome in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 192, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.001 (2018).

Harvey, P. D., Khan, A. & Keefe, R. S. E. Using the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) to define different domains of negative symptoms: Prediction of everyday functioning by impairments in emotional expression and emotional experience. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 14(11–12), 18–22 (2017).

Harvey, P. D. & Strassnig, M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: Cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry 11(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.004 (2012).

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn. (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13(2), 261–276 (1987).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (The Psychological Corporation, 1997).

Matsuoka, K., Uno, M., Kasai, K., Koyama, K. & Kim, Y. Estimation of premorbid IQ in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease using Japanese ideographic script (Kanji) compound words: Japanese version of National Adult Reading Test. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 60(3), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01510.x (2006).

Weickert, T. W. et al. Cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia displaying preserved and compromised intellect. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57(9), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.907 (2000).

Kern, R. S. et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: Co-norming and standardization. Am. J. Psychiatry 165(2), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010043 (2008).

Nuechterlein, K. H. et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: Test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatry 165(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042 (2008).

Fujino, H. et al. Performance on the Wechsler adult intelligence scale-III in Japanese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 68(7), 534–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12165 (2014).

Birchwood, M., Smith, J., Cochrane, R., Wetton, S. & Copestake, S. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 157, 853–859 (1990).

Nemoto, T. et al. Reliability and validity of the Social Functioning Scale Japanese version (SFS-J). Jpn. Bull. Soc. Psychiat. 17, 188–195 (2008).

Ohi, K. et al. A 1.5-year longitudinal study of social activity in patients with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 10, 567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00567 (2019).

Pawliuk, N. et al. Adapting, updating and translating the Social Functioning Scale to assess social, recreational and independent functioning among youth with psychosis in diverse sociocultural contexts. Early Interv. Psychiatry 16(7), 812–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13231 (2022).

Hasegawa, N. et al. Effect of education regarding treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and depression on the treatment behavior of psychiatrists: A multicenter study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 77(10), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13578 (2023).

Sergi, M. J. et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia: relationships with neurocognition and negative symptoms. Schizophr. Res. 90(1–3), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.028 (2007).

Reddy, L. F., Llerena, K. & Kern, R. S. Predictors of employment in schizophrenia: The importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Schizophr. Res. 176(2), 462–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.08.006 (2016).

Harvey, P. D. & Pinkham, A. Impaired self-assessment in schizophrenia: Why patients misjudge their cognition and functioning. Curr. Psychiatry 14(4), 53–59 (2015).

Gould, F., Sabbag, S., Durand, D., Patterson, T. L. & Harvey, P. D. Self-assessment of functional ability in schizophrenia: Milestone achievement and its relationship to accuracy of self-evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 207(1–2), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.035 (2013).

Miyata, J. et al. Associations of conservatism and jumping to conclusions biases with aberrant salience and default mode network. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 78(5), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13652 (2024).

Strassnig, M. et al. Which levels of cognitive impairments and negative symptoms are related to functional deficits in schizophrenia?. J. Psychiatr. Res. 104, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.06.018 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the individuals who participated in this study.

Funding

CS received funding from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP20K03433. RH received Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP21wm0425012, JP21uk1024002, JP21dk0307103, JP22tm0424222; Brain/MINDS & beyond studies Grant Number 24dk0307132 from the AMED; the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) JP20H03611; the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research JP19H05467, and Intramural Research Grant for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP (3-1, 6–1). TS received funding from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant No. JP23H03610; the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant for Comprehensive Research on Persons with Disabilities from AMED (JP24dk0307114); and Intramural Research Grant for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP (5-3, 6–1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS designed the study and wrote the manuscript. RH supervised it. TS revised the draft critically for important intellectual content. JM, HY, MF, and YY collected data. SI reviewed the analyses. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sumiyoshi, C., Ito, S., Matsumoto, J. et al. Predicting models for work outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and its clinical application. Sci Rep 15, 15308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99871-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99871-3