Abstract

This research aims to conduct an exergy, economic, and environmental analysis of a 6.57 kWp rooftop photovoltaic (PV) power plant that combines different PV technologies, comprising 2 kWp of poly-crystalline (p-Si), 1.87 kWp of mono-crystalline (m-Si), and 2.7 kWp of thin-film amorphous silicon (a-Si) technologies. A comprehensive assessment was conducted to evaluate the environmental and techno-economic parameters of a PV plant system. This study is based on the performance data obtained over four years of energy production under the weather conditions of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The embodied energy required for the manufacturing of the PV power plant was estimated using embodied energy indices available in the literature. Additionally, a detailed economic evaluation was conducted based on the electricity costs in Malaysia. Moreover, the environmental impact was assessed over the plant’s life cycle, considering the emission factors of coal power plants. Results indicate that the exergy payback time for the different technologies i.e., m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, when operated individually, and when combined within a single PV system, are found to be ~ \(10, 4.2, 2.4\), and \(6.3\) years, respectively. Over its life cycle, it was found that the PV plant emits about \({39.3\text{ tCO}}_{2}\). Emission breakdown analysis has revealed that the manufacturing process of the m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, and the monitoring systems contribute to \(32.4{\%}\), \(22.4{\%}\), \(17.3{\%}\), and \(27.8{\%}\) of \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emissions, respectively. However, the PV power plant could offset about \(6.2\text{ t}{\text{CO}}_{2}\) annually, equivalent to the emission of a car over approximately 3 years. This study offers critical insights into the exergy efficiency, environmental impact, and economic viability of a grid-connected rooftop PV power plant that integrates multiple PV technologies under tropical climate conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photovoltaic (PV) panels are devices that transform sunlight into electrical energy through the displacement of electrons in a semiconductor material after being excited by photons, generating an electric current. PV cells, as electronic devices, can generate electricity with zero carbon emissions1. These devices come in various shapes, sizes, and semiconductor materials. However, their electrical output can be influenced by several factors, including operating conditions, installation angle, and the technologies used in PV cell materials2. In the last decade, there has been significant interest in the solar system industry regarding the development of PV cell materials and technology to enhance PV module performance, increase efficiency, lower module prices, and reduce carbon emissions2,3. Solar PV cells can be developed using single-junction or multi-junction light-absorbing materials. PV modules are typically classified into three generations. Conventional panels built with crystalline silicon (c-Si), such as mono c-Si, are considered to be the first cell generation4. Thin-film solar cells form the basis of the second generation5, while the non-silicon-based technologies are considered as the third cell generation1.

The techno-economic performances of PV systems based on different generations have been intensively investigated by several researchers worldwide6,7,8,9,10. Tahri et al.11 investigated the performances of two different PV systems based on mc-Si (multi-crystalline) and CIS (copper indium selenium) modules. The obtained result shows that the mc-Si outperforms CIS by an average of 5.53% in annual average daily performance. Farhoodnea et al.12, investigate the output of 3-kWp grid-connected PV system based on a p-Si (poly-crystalline) module. The output of the PV system is assessed under operating conditions typical of Malaysia. The experimental findings indicate that the average efficiency of the PV panel is approximately 10.11%, while that of the inverter is about 95.15%. Meanwhile, the average monthly PV output ratio of the system is about 77.28%, and the average capacity factor is about 15.70%. Adouane et al.13, compared the performances of eight different PV module technologies under Kuwait’s operating weather conditions. In which the investigated PV modules are based on the eight m-Si, p-Si, HIT (Heterojunction), thin film, CIGS (Copper Indium Gallium Diselenide), CdTe (Cadmium Telluride), and a-Si (Amorphous Silicon). The results indicate that the geometry and materials used in PV module construction had a notable influence on its temperature, soiling loss, and overall performance. Notably, the modules based on m-Si, p-Si, and HIT technologies demonstrated enhanced performance under high solar radiation. Meanwhile, the HIT module outperformed m-Si and p-Si panels. Sharma and Goel14 investigated the performance of an 11.2 kWp rooftop grid-connected PV system under Indian weather conditions. The result shows that the p-Si PV system produced about 14.960 MWh from September 2014 to August 2015. For similar weather conditions, the performances of the PV module based on m-Si, CdTe, a-Si, and CIS cell technologies are evaluated numerically and experimentally by Shukla et al.15. The results indicate that the a-Si system achieves higher performance compared to the other PV systems.

The environmental impact of the life cycle assessment (LCA) of the different PV technologies is investigated in several published works. Akinyele et al.16 investigate the life cycle impact of a 1.5 kW PV system based on m-Si PV technology under the weather conditions of six places in Nigeria. The analyses include life cycle emission rate (LCER), cumulative energy demand (CED), global warming potential (GWP), net energy ratio (NER), and energy payback time (EPT). The results show that with a performance ratio of 80%, solar irradiation ranging from 1493 to 2223 kWh/m2/year, module efficiency of 15.4%, lifetime of 20–30 years, CED of 3800 to 8700 MJ eq., and LCER of 37.3 to 72.2 g CO2/kWh, the GWP, NER, and EPT values range from 1907 to 5819 kg CO2-eq., 7.08 to 36.17, and 0.83 to 2.3 years, respectively. Lunardi et al.17, investigate the environmental impacts of solar modules based on Si and chalcogenide/Si technologies in terms of GWP, energy payback time, human toxicity potential, freshwater eutrophication potential, abiotic depletion potential, and freshwater ecotoxicity potential. The findings of Lunardi’s study indicate that when contrasted with Si, Copper Indium Gallium Selenide (CIGS/Si) exhibits more unfavorable environmental effects across most categories. However, in contrast, Copper Zinc Tin Sulfide (CZTS/Si) and Ag2ZnSnSe4 (AZTS/Si) demonstrate superior outcomes across the majority of impact categories. Luo et al.18 conducted the LCA of PV system based on multi-Si technologies operated under Singapore weather conditions, of which a comparative analysis is presented for three different configurations, namely, aluminum back surface field, solar cells with the frameless double-glass module structure, and passivated emitter and rear cell PV systems. Yadav et al.19 analyzed the effect of temperature on the overall outputs and the environmental impact of a 5 kWp rooftop PV plant. The obtained results show that the p-Si PV system performed about 5.23 kWh/kW/day, 3.99 kWh/kWp/day, and 4.51 kWh/kWp/day for the annual average reference yield, the final yield of the plant and array yield. The conducted PV system reduced the emission of 7.032 tons of CO2 for one year. R. P. et al.20 analyzed the performances of two PV systems based on p-Si and CIS technology operated under Indian weather conditions. In which the embodied energy, life cycle conversion efficiency (LCCE), energy production factor (EPF), and EPBT of the conducted PV systems are evaluated. The results show that the energy output is 5.13 and 6.02 kWh/day for p-Si and CIS in the summer, while that in the winter is about 3.96 and 4.63 kWh/day, respectively. The EPBT for CIS and p-Si technologies has been estimated to be 0.989 and 4.331 years, respectively. Goswami and Aizpurua21 investigate the techno-economic assessment of floating solar photovoltaic (FPV) systems under Indian weather conditions, and compare the results with those of ground-based photovoltaic (GPV) systems. The findings indicate that, although FPV systems have a higher failure rate, their energy generation is 5.38% higher than that of comparable GPV systems, assuming standard maintenance. The LCOE for FPV systems with normal maintenance is 0.0551 $/kWh, which is competitive with that of GPV systems. However, reduced maintenance leads to a higher LCOE for FPV systems compared to GPV systems. Chang et al.22 highlights material-related bottlenecks to encourage further research and facilitate organic PV’s commercialization. Akhter et al.23, evaluate the outputs of combined-grid-connected PV systems based on m-Si, p-Si, and a-Si modules type. These systems were installed on the rooftop of the faculty of engineering at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The obtained results show that the annual average AC energy for a-Si is 3293.2 kWh, p-Si is 2435.8 kWh, m-Si is 1425.6 kWh, and combined PV systems are 7172.3 kWh. In addition, the combined PV system can avoid about 7035.9 kg of CO2 over one production year.

Based on the literature reviewed, the performance of PV systems using various technologies under different weather conditions has been assessed. However, many published works lack analysis regarding these PV systems’ life cycle assessment, techno-economic evaluation, and environmental impact. Conversely, the study by Akhter et al.23 requires further investigation into these areas, particularly regarding life cycle assessment, environmental impact during manufacturing and production phases, and techno-economic analysis of the PV system studied. This work aims to fill these gaps by presenting a comprehensive life cycle assessment, environmental impact assessment, and techno-economic evaluation of a small PV power plant with three PV cell technologies installed on the rooftop of the engineering faculty building at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The present study builds upon the previous work conducted by Akhter et al.23, providing a thorough examination of the technical, economic, and environmental aspects of the micro PV power system.

The need of LCA analysis for PV system and the main contributions of the present study

The focus on the analysis of performance of PV system alone is insufficient, as it fails to account for the full environmental footprint, including manufacturing, resource extraction, and waste management24,25. LCA is essential for understanding the environmental impacts of PV systems across their lifespan, helping to evaluate sustainability from material selection to end-of-life management. This approach quantifies emissions, EPBT, and cumulative energy demand (CED)25. With the rapid evolution of PV technology, updated LCA data is crucial to avoid inaccuracies26. LCA can inform policy, particularly in fossil fuel-dependent regions27, and assess the broader environmental benefits of renewable systems, such as PV integration into virtual power plants28. Optimizing PV layouts using LCA can significantly reduce their environmental impact29. While LCA optimizes PV systems, it must also consider trade-offs, including economic feasibility and technological constraints.

Different PV technologies, such as silicon-based, thin-film, and emerging alternatives, show significant variations in environmental impact and cost-effectiveness. Several studies on the system LCA for different type of PV system show a different rate of carbon emissions and economic benefits for example, silicon-based systems, though reliable, have a global warming potential of 40–200 gCO2eq/kWh30 and an energy-intensive manufacturing process31. Meanwhile, thin-film technologies like CdTe and a-Si exhibit lower emissions (22–40 gCO2eq/kWh)30, requiring fewer materials and reducing environmental impacts31. Emerging technologies, including OPVs and perovskite cells, show high variability in impact, with perovskite reaching up to 1000 gCO2eq/kWh30. Manufacturing and transportation, particularly the construction phase (85.7% of total emissions) and sea freight, are significant contributors to emissions32. End-of-life management remains a critical but under-researched area30, highlighting the need for further refinement of LCA methodologies to improve the reliability of sustainability assessments across PV technologies. Therefore, the present study provides valuable insights into the behaviour of different PV systems under tropical weather conditions. By analysing their performance in this context, the study contributes to ongoing efforts aimed at improving the efficiency of PV systems for electricity production while simultaneously reducing carbon emissions. These findings support the advancement of sustainable energy solutions tailored to tropical climates. The key contributions of this study, which offer valuable insights into optimizing PV systems for tropical environments and advancing both scientific knowledge and practical applications, are as follows:

-

1. Comprehensive LCA for Hybrid PV Integration is introduced to explore the synergies of combined m-Si, p-Si, and a-Si systems, enhancing system performance in tropical climates.

-

2. The study introduces Exergy Payback Time (ExPBT), offering a more comprehensive sustainability evaluation that highlights the resilience of PV system in tropical environments.

-

3. The study includes emissions from non-generation components (e.g., monitoring systems), providing a more accurate and complete life-cycle environmental impact assessment.

-

4. Localized techno-economic evaluation has presented using region-specific data to offer targeted economic insights, particularly for Southeast Asia.

-

5. The economic impact of carbon credits and taxes is examined, demonstrating the financial viability of the presented PV system technology.

Methods

The method and the process of conducting the LCA of the PV systems are outlined in the present section. The system component and dimension, the necessary mathematical equations for evaluating the system’s output, the environmental impact, and economic analysis over the life cycle period are summarized in this section.

Analyzed PV systems

In this section, an overview of the grid-connected PEARL’s lab PV system, detailing its system description, dimension, and collecting data system will be provided.

System description

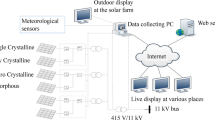

The PEARL PV system comprises three types of PV array technologies oriented towards the south with tilt (inclination) angle 10°, respectively. With latitudes and longitudes coordinates of 3.07o N and 101.39o E, respectively. The installation of the system conforms to the IER61730 standard, which is authorized by the Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA), which oversees renewable energy projects in Malaysia. Figure 1 illustrates an overview of PEARL’s PV System.

PV technology and inverter

The PEARL PV system was first installed back in October 2015 and has been continuously operated since then. The system comprises three types of PV modules: Polycrystalline (p-Si), Thin Film (a-Si), and Monocrystalline (m-Si), as depicted in Fig. 2D. Specifically, p-Si, a-Si, and m-Si modules are represented by systems A, B, and C in Fig. 2. The main characteristics of the PV modules that were conducted are presented in Table 1. The dimension presentation of each PV system is illustrated in Fig. 3 (Table 2), and the measurement of each PV’s module in the PEARL system is summarized in Table 3.

PV monitoring system

SMA Sunny Sensor box was installed to capture and record all measurements, such as irradiance and temperature. This sensor box is positioned directly on the module to gauge solar irradiance, temperature (both ambient and module), and wind speed. The SMA power injector powers the sensor box, which is linked to the SMA SUNNY WEBBOX by a communication bus. The Sunny Web Box is an effective monitoring solution for both small and large PV systems. The primary purpose of the Web Box is to gather, store the current and pass measurements, and lastly, offer round-the-clock measurements to the customer. The Sunny Web Box logs and monitors data measurements via a local network and a desktop computer. Meteorological data can be retrieved via Sunny Portal at intervals of 5, 15, or 30 min, depending on the user’s requirements.

The laboratory is equipped with a personal computer (PC) for data collection, which is accessible to both students and lecturers. All the collected data from the data logger is able to sustain long-term storage for up to 12 months. Figure 4 shows the location and position of the data logger, PC monitoring, and the inverter in the PEARL laboratory.

Life cycle assessment

LCA of the analyzed PV systems is a comprehensive approach to evaluating the flow of energy from their manufacturing phase until their end-of-life period. This section illustrates the necessary approach for assessing the energy behaviors of the PV modules that were conducted.

In this study, several assumptions are made to facilitate calculations and enhance the clarity of the system’s performance analysis. The energy production of the PV system is modeled based on typical seasonal variations, with efficiency losses incorporated in accordance with the previous study by Akhter et al.23. It is assumed that the system’s efficiency declines at a constant annual rate over its 25-year lifespan. Regarding economic feasibility, all installation and system component costs are derived from prevailing market prices, while maintenance expenses over the system’s lifespan are considered negligible. However, variability in solar radiation due to weather or environmental factors represents a critical contingency that could impact both energy production and overall system performance. Additionally, advancements in PV technology, particularly improvements in efficiency or reductions in costs, may influence the expected performance and economic viability of the system.

Exergy payback time

For renewable energy systems, the exergy payback period is an essential factor in knowing the necessary time for payback of the exergy used throughout the life cycle phases, including manufacturing, installation, maintenance, and operation33. This factor allows for the assessment of the system’s viability from an environmental and economic standpoint34. The conducted PV system’s payback time is evaluated using Eq. (1):

where \(\text{CExC}\) is the cumulative exergy consumption, which is estimated by using the efficiency conversion factor of coal power plants to electricity (i.e., 0.36 of the total embodied energy). \({\text{E}}_{\text{y}}\) represent the annual collected electrical energy output for each PV system.

The benefit time (\(\text{ExBT}\)) is the time between the end of \(\text{ExPBT}\) and the end-of-life cycle (\(\text{LCT}\)). It can be calculated as follows:

The energy return on investment can be estimated as follows35:

Levelized cost of electricity

The \(\text{LCOE}\) is a factor used for evaluating the cost of electricity generated from an PV power plant during a particular period. In the present analysis, the \(\text{LCOE}\) for the studied PV systems is estimated to assess the economic reliability of the rooftop PV system. It is important to note that the economic assessment performance includes only the initial capital cost for each PV system and its operating system cost. Thus, maintenance cost over the LCT is estimated to be negligible. Furthermore, the Straight-Line Depreciation method is employed for LCOE calculation. This approach evenly distributes the initial capital investment over the system’s lifetime, ensuring a consistent annual depreciation expense. Therefore, the \(\text{LCOE}\) can calculated as follows36:

where: \(\text{LCC}\) and \({\text{E}}_{\text{LCT}}\) are the life cycle cost and energy produced over the lifetime, respectively.

Economic benefits

After estimating the benefits time and the annual production for the conducted PV modules, estimating the outcome economic benefits is required. The conducted PV system is a grid-connected system that is considered suitable for domestic use; therefore, the electricity prices are for the household rate in Malaysia (i.e \(.,{\text{C}}_{\text{e}}= 0.045\text{ \$}/\text{ kWh}\)). The economic benefits can be calculated as follows:

Environmental impact

PV systems are among the most cleanest renewable energy sources during their operating phase. This is due to the clean conversion process of solar light to electricity using PV panels. However, the manufacturing phase of the PV panel could cause many environmental impacts, particularly concerning emissions such as carbon dioxide emissions and the potential for global warming. Therefore, evaluating the environmental impact of the assessed rooftop PV systems over the phases of manufacturing and production of each subsystem is required. Equations (6) and (7) are used to estimate the amount of emission during the manufacturing phase and the avoided amount of emission during the production phase, respectively.

where: \({\text{F}}_{\text{i}}\) is the factor of emission referred to the coal power plant, \(\text{i}\) represent pollute element (i.e., the considered pollutants in the present study are \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) and \(\text{GWP}\)). In which the corresponding emission factor for \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) and \(\text{GWP}\) are \(0.523\text{ kg}/\text{kW}\) and \(0.565\text{ kg }{\text{CO}}_{2}.\text{eq}. {\text{m}}^{-2} {\text{yr}}^{-1}\)37.

The CO2 credit (\({\text{Z}}_{{\text{CO}}_{2}}\)) is another parameter evaluated in this study to assess the environmental benefits of the conducted PV system. The \({\text{Z}}_{{\text{CO}}_{2}}\) can be estimated as follows38:

where, the \({\text{z}}_{{\text{CO}}_{2}}\) is the carbon credit is estimated to be \(14.5\text{ \$}/\text{ton}\)38, \({\text{PS}}_{{\text{CO}}_{2}}\) is the mitigate CO2 over one year. The specific carbon credit \({\text{Z}}_{{\text{ACO}}_{2}}\) can estimated using Eq. (16):

where A is the specific area of the assessed rooftop PV system.

The carbon tax is a crucial aspect for assessing both the environmental and economic viability of PV systems. This measure has been introduced in numerous countries globally to incentivize the adoption of renewable energy sources and mitigate carbon emissions. In the present study, the carbon tax is set at \(15\text{ \$}/\text{ton}.\text{m}\) of carbon39.

PV system losses and degradation

The PEARL Lab PV system has been installed at an appropriate distance in compliance with IEC 61730 standards, which are adhered to by the Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA). The system’s tilt angle has been optimized to 10º to minimize shading and irradiation losses. Furthermore, previous studies by Akhter et al.23 have evaluated the remaining losses, including array losses, system losses, and overall losses for the PEARL PV system. Their comprehensive analysis revealed seasonal variations, with losses generally higher in sunny seasons than in rainy seasons, indicating reduced array performance under intense solar conditions. Additionally, the power degradation of the PEARL Lab PV system was assessed by the same authors, which accounted for the gradual decrease in system performance over time. The result show that the p-Si have less degradations in all the performance compared to the a-Si and m-Si. Therefore, in the present study, loss calculations and power degradation rates are not performed, and the results reported by Akhter et al.23 are considered to avoid further calculations.

Result and discussion

In this section, the LCA of the three different kinds of PV modules is presented and discussed. Besides, the energy assessment, economic assessment, environmental impact, and benefits are also investigated and presented.

Energy evaluation of the combined PV system

This section evaluates and fairly estimates the energies required by the analyzed rooftop PV power system during its manufacturing and operating phases. The main findings of this assessment are outlined in Table 4.

During the manufacturing and installation phases, the combined PV system, including the m-Si, a-Si, p-Si, and monitoring systems, consumed about \(45302\text{ kWh},\) equivalent to \(755.38\text{ kWh}/{\text{m}}^{2}\), where the total required embodied energy during the manufacturing phase is about \(125840\text{ kWh}\). Meanwhile, the energy consumed by the m-Si system is higher by 6863.7 and 4525 kWh compared to the a-Si and p-Si systems, respectively. This is because the m-Si system consumes higher embodied energy than the other conducted system. It should be noted that the monitoring system embodied is only included in the case of a combined PV system.

The electrical performances of the conducted PV systems are measured and collected for four operating years, in which the overall outputs of m-Si, a-Si, and p-Si systems are collected separately, and the obtained results are provided in Table 4. As it can be observed in Table 4, the overall performance for the a-Si system is higher by \(857.4\) and \(1867.6\text{ kWh}\) compared to the p-Si, and m-Si systems, respectively. This higher output allows the a-Si system to share about \(46{\%}\) of the overall electrical energy of the combined PV system. On the other hand, the p-Si system, and m-Si system share about \(43{\%},\) and \(19.9{\%}\) m respectively in overall electrical energy of the combined PV system. The average total energy production supplied to the connected grid by the combined PV system for 4 operating years is approximately \(7172.3\text{ kWh}\)40.

Economic assessment of the different rooftop PV system configurations

After calculating and measuring the energy consumption and production of the studied rooftop combined PV system, an evaluation of the required cost for realization and operation, along with the saving cost of the PV system, is conducted. Thus, the economic assessment of the PV system, including the capital cost, cost saving, and levelized cost of energy, are evaluated in this section and presented in Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, the m-Si system exhibits a lower capital cost compared to the p-Si system and the a-Si system. That is, the capital cost of the m-Si system represents about \(19.2{\%}\) of the overall capital cost for the combined PV system, while the capital costs for both the p-Si system and a-Si system represent approximately \(26.6{\%}\), and \(36.1{\%}\) of the overall capital cost for the combined PV system, respectively. On the other hand, the LCOE of the rooftop combined 6.57 kWp PV system is about \(\text{RM }0.6315/\text{kWh},\) which is higher by \(3.7{\%}, 21.93{\%}\), and \(21.61{\%}\) against the m-Si system, p-Si system, and a-Si system, respectively. This can be explained by the fact that the higher \(\text{LCOE}\) for the combined PV system compared to the other PV subsystems is due to the high capital cost for the monitoring system, which represents about \(17.7{\%}\) of the overall capital cost. The \(\text{LCOE}\) for the combined PV system is deemed reasonable compared to previously published works on PV systems operated in Malaysia. It was determined to be \(0.9170\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\) by C.Y.Lau et al.45. Additionally, Laajimi and Go46 reported that LCOEs in Malaysia could be approximately \(0.4354\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\), \(0.4194\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\), \(0.4222\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\), and \(0.4609\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\) for \(50\text{ MW}\), \(30\text{ MW}\), \(10\text{ MW}\), and \(6\text{ MW}\) projects, respectively. Azmana et al.47 found an LCOE of approximately \(0.584\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}.\)

The cost saving of the different studied PV configurations relies on three major factors: the average annual production, the benefits time of each system, and the cost of produced electricity. The combined PV system saves about \(29117\text{ RM}\) during the benefit time. In comparison, the m-Si system, a-Si, system, and p-Si system save about \(4566\text{ RM}\), \(16241\text{ RM}\), and \(11058\text{ RM}\), respectively. It is important to note that the saving cost calculation is based on the average cost of electricity in Malaysia, which is about \(0.218\text{ RM}/\text{kWh}\).

Energy performance indicators output

The \(\text{ExPBT}\), \(\text{ExBT}\), and \(\text{EROI}\) are specific indicators for analyzing the profitability of the studied PV systems. It is worth noting that the previously mentioned indicators primarily rely on the energy performance of the system, whether consumed or produced, during its life cycle. The results of these performance indicators are presented in Table 6. As shown in the table, the m-Si system emerges as the least favorable option based on all assessed performance indicators. Precisely, the \(\text{ExPBT}\) for the m-Si PV system is calculated to be approximately 10 years, surpassing the values for the p-Si system, a-Si system, and the combined PV system by 5.86, 7.66, and 3.7 years, respectively. Hence, the m-Si system is deemed a less practical energy choice compared to other PV technology systems, primarily due to its predicted \(\text{EROI}\) falling below the minimum \(\text{EROI}\) necessary for sustaining modern industrial society in the developed world (set at 3:1)48. On the contrary, the a-Si system stands out as the most efficient in terms of energy savings over its operational lifespan, surpassing both p-Si and m-Si systems. Approximately 55.78% of the total energy savings of the combined PV system are attributed to the a-Si system, whereas p-Si and m-Si systems contribute 37.98% and 22.42%, respectively. The a-Si system is considered to be the most recommended PV technology option due to its elevated \(\text{EROI}\) of about 10.51, surpassing values for m-Si and p-Si systems by 8.08 and 4.43, respectively. On the other hand, the combined PV system required approximately 6.33 years to offset its primary consumed energy during the manufacturing phase. This period is considered ideal for a large-scale system, as the recommended \(\text{ExPBT}\) for PV systems extends up to 10 years49. The \(\text{EROI}\) for the combined PV system is calculated to be 3.95, affirming its status as a practical energy option as well.

Environmental impact of conducted PV systems

PV power plants play an important role in reducing reliance on traditional fossil fuels, thereby decreasing ecosystem deterioration and mitigating climate change. However, the manufacturing phase of these devices emits huge amounts of pollutants, particularly carbon emissions. The environmental impact over the manufacturing phase and the potential avoided emissions for the different studied PV technologies have been fairly evaluated, and the obtained data are presented in Table 7. It has been observed that the m-Si system exhibits higher pollution levels compared to other PV systems in terms of \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emissions and \(\text{GWP}\). This is explained by the high exergy consumption during its manufacturing phase. The manufacturing process of the m-Si system contributes to \(12.75\text{ tons }{\text{CO}}_{2}\) emissions, exceeding those of the p-Si system and a-Si system by \(3.927\) and \(5.957\text{ tons }{\text{CO}}_{2}\), respectively. The m-Si system also contributes approximately \(13.401\text{ tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2} .\text{eq}\) in \(\text{GWP}\). On the other hand, the combined PV system emits approximately \({39.322\text{ tons CO}}_{2}\). This total includes the \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emissions from the manufacturing phases of the m-Si system, p-Si system, a-Si system, and the monitoring system. The distribution of these emissions is as follows: \(32.43{\%}\) for the m-Si system, \(22.45{\%}\) for the p-Si system, \(17.28{\%}\) for the a-Si system, and \(27.84{\%}\) for the monitoring system. The combined PV system emits around \(41.316\text{ tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2} .\text{eq}\) in \(\text{GWP}\). Overall, the a-Si system is considered a cleaner option compared to other PV systems due to its lower carbon emissions, particularly in comparison to the m-Si PV and p-Si systems. The a-Si system emits about \(6.79\text{ tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2}\) which is equivalent to \(22.98{\%}\) and \(46.72{\%}\) less than the p-Si PV and m-Si systems, respectively.

The mitigation carbon amount is also estimated in this study, and the findings that were obtained are listed in Table 7. It has been observed that the a-Si system is the greenest in terms of mitigated carbon and GWP contribution. The a-Si system mitigates about \(2.86\text{ tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission during one year of production, which is higher by \(56.64{\%}\) and \(26.22{\%}\) compared to m-Si PV and p-Si systems, respectively. In addition, \(1{\text{m}}^{2}\) of a-Si system can avoid \(102.14\text{ kg}{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{yr}\), whereas \(1{\text{m}}^{2}\) m-Si PV and p-Si systems can only avoid \(81.55\) and \(125.85\) \(\text{kg}.{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{yr}\), respectively. Meanwhile, the combined PV system can mitigate about \(6.2\text{ tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2}\) over one year of electricity generation, equivalent to \(103.38\) \(\text{kg}.{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{yr}\) for every \(1{\text{m}}^{2}\) of the combined PV system. Furthermore, a forecasted \(\text{GWP}\) contribution avoidance of \(\text{163,25 tons}.{\text{CO}}_{2}.\text{eq}\) over the life cycle time has been projected for the combined PV system.

Table 8 presents the carbon taxes, carbon credits, and specific carbon credits per year for the different PV systems. According to Table 8, the carbon credit for the combined PV system, a-Si, p-Si, and m-Si systems is about \(89.9, 41.47, 30.6\), and \(17.98\text{ \$}/\text{yr},\) respectively. In addition, the specific carbon credits have been found to be approximately equal to \(1.68, 5.41, 1.034\), and \(1.07\text{ \$}/\text{yr}.{\text{m}}^{2}\) for the combined PV system, a-Si, p-Si, and m-Si systems, respectively. Overall, the combined PV system shows a higher carbon credit due to its higher carbon mitigation.

In the present study, carbon taxes were considered, and the obtained results are presented in Table 8. It was found that the carbon tax for the combined PV system over its manufacturing phase was approximately \(9.85\text{ \$}/\text{ton}\) for each square meter of the system. This figure is \(21.64{\%}\) lower compared to m-Si, and higher by \(63.05{\%}\) and \(19.63{\%}\) compared to a-Si and p-Si, respectively. Regarding avoided taxes, the 1 m2 combined PV system shows approximately \(38.77\) \(\text{\$}/\text{ton}\) over its production phase. This is \(21.12{\%}\) and \(1.2{\%}\) higher against the m-Si and a-Si systems, respectively, and \(17.84{\%}\) lower compared to p-Si.

Table 9 shows the equivalent \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission in day-to-day commodities. As can be seen from Table 9, the mitigated \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission for the combined PV system is equivalent to \(1.15\text{ cars}\) not used, \(2927.8\text{ L}\) of avoided gasoline, \(14.26\text{ barrels}\) of avoided crude oil, \(1.36\text{ acres}\) absorbed by forest, and \(2.14\text{ tons}\) of waste recycling. Conversely, the a-Si PV system is considered the best green option compared to m-Si and p-Si in terms of all estimated equivalent \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission in day-to-day commodities. For example, the a-Si PV system avoids about \(1350.5\text{ L}\) of gasoline, which is higher by \(764.9\) and \(345.1\text{ L}\) compared to m-Si and p-Si, respectively. On the other hand, the amounts of CO2 avoided over one year for m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, and the combined PV system are estimated to be equivalent to the emissions of a car over 3 months and 10 days, 5 months, and 15 days, 7 months and 14 days, and 1 year and 10 days, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis of the pearl lab PV system

Sensitivity analysis is crucial for understanding how small changes in system components or external conditions may affect the overall performance and sustainability of a system. In this study, the sensitivity analysis of the rooftop PV system is conducted by evaluating the variability and impact of different system configurations and PV materials on energy performance, economic outcomes, and environmental benefits. Thus, the material types, the results indicate i.e. embodied energy, that the type of PV material significantly impacts the overall energy consumption during both the manufacturing and production phases. The sensitivity analysis of embodied energy and energy output reveals that the a-Si PV module is the most energy-efficient option compared to other systems, owing to its lower initial energy requirements and higher energy output. Furthermore, while the capital cost of a-Si is higher, its energy efficiency and return on investment make it a more viable choice for long-term sustainability.

On the other hand, PV systems are highly sensitive to operating weather conditions such as solar radiation, ambient temperature, humidity, and wind speed. Consequently, the performance of PV systems in Malaysia is significantly affected by its tropical climate. Solar irradiance fluctuates due to cloud cover and monsoons, leading to reduced energy yield. Elevated temperatures degrade PV efficiency, while high humidity accelerates material degradation. Although rainfall helps clean the panels, it temporarily reduces power output. Sensitivity analysis highlights considerable performance variations, necessitating mitigation strategies such as cooling systems, energy management systems, and hybrid solar systems to enhance efficiency and longevity under Malaysia’s challenging weather conditions.

Comparative analysis of emission per kWh of generated electricity over the LCT

To assess the environmental cleanliness of the studied rooftop PV system, a comparative analysis on the emission per kWh of generated electricity over the lifetime period is conducted between the present PV systems and similar studies under different climate conditions worldwide. Details about the findings are presented in Table 10. As can be seen, compared to similar PV technologies, the implemented m-Si PV system exhibits higher EPBT and carbon emissions than its counterparts in Japan, Korea, Southern Europe, and Brazil. Conversely, the p-Si PV system in this study demonstrates an average carbon emission of \(21.56\) \(\text{g}.{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{kWh}\), aligning with emissions from p-Si PV systems installed in Japan and registering lower emissions compared to those in Korea and Southern Europe. Notably, in China, the p-Si PV system demonstrates lower equivalent carbon emissions than observed in this study.

The a-Si PV system in the present assessment exhibits lower equivalent carbon emissions than other installed a-Si systems worldwide. Furthermore, the \(EPBT\) for the a-Si PV system in the present assessment is in line with that presented in previous studies55,57,58,59. Additionally, the combined PV system showcased in this study demonstrates lower equivalent carbon emissions compared to other systems, with an estimated emission amount of approximately \(10.29\text{ g}.{\text{CO}}_{2}\) per one \(\text{kWh}\) of produced electrical energy.

Overall, the combined rooftop PV system presented in this study, comprising m-Si, p-Si, and a-Si technologies, demonstrates acceptable energy performance and carbon footprint. Moreover, the yearly performance indicators of the a-Si system surpass those of m-Si and p-Si PV systems in terms of carbon footprint per kWh of generated electricity. That is, the a-Si system emerges as the optimal choice for the site under consideration, owing to its superior array yield and lower carbon emissions in comparison to the other two PV systems.

Conclusion

In this study, a comprehensive 3E analysis of an existing rooftop PV power plant combining monocrystalline and polycrystalline silicone PV cell technologies has been carried out. The main finding of the present study can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

The total required primary energy for the combined PV system, including the m-Si system, a-Si system, p-Si system, and monitoring system, is about \(755.38 kWh/{m}^{2}\).

-

2.

The required primary energy for the m-Si system is higher by \(37.23{\%}\) and \(71.59{\%}\) compared to the p-Si and a-Si systems, respectively.

-

3.

The capital cost of the m-Si, p-Si, and a-Si systems presents about \(19.18{\%}, 26.58{\%},\) and \(36.08{\%}\) of the overall capital cost of the combined PV system, respectively.

-

4.

The \(LCOE\) for the combined PV system is about \(RM0.6315,\) which is higher by \(3.7{\%}, 21.93{\%}\), and \(21.61{\%}\) against the m-Si system, p-Si system, and a-Si system, respectively.

-

5.

The combined PV system saves about \(RM\text{29,117}\) during the benefit time. Whereas the m-Si system, p-Si system, and a-Si system save about \(RM\text{4,566}\), \(RM\text{11,058}\), and \(RM\text{16,241}\), respectively.

-

6.

The \(ExPBT\) for the m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, and the combined PV systems are estimated to be 10.03, 4.17, 2.37, and 6. 33 years, respectively.

-

7.

The combined PV system emits approximately \({39.322\text{ tCO}}_{2}\). This includes \(32.43{\%}\), \(22.45{\%}\),\(17.28{\%}\), \(27.84{\%}\) of \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emissions from the manufacturing phases of the m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, and the monitoring systems, respectively.

-

8.

The a-Si system mitigates about \(2.86\text{ t}{\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission during one year of electricity production. Which is higher by \(1.62\) and \(0.75\text{ t}{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{yr}\) compared to m-Si PV and p-Si systems, respectively.

-

9.

The combined PV system can mitigate about \(6.2\text{ t}{\text{CO}}_{2}\) over one production year, which is equivalent to \(116.19\text{ kg}.{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{yr}\) for every \(1{\text{m}}^{2}\) of the combined PV system.

-

10.

The carbon credit for the combined PV system, a-Si, p-Si, and m-Si systems is about \(89.9, 41.47, 30.6\), and \(17.98\text{ \$}/\text{yr},\) respectively.

-

11.

The specific carbon credit is about \(1.68, 5.41, 1.034\), and \(1.07\text{ \$}/\text{yr}.{\text{m}}^{2}\) for the combined PV system, a-Si, p-Si, and m-Si systems, respectively.

-

12.

The carbon footprint per \(1\text{kWh}\) of the generated electricity by the m-Si, p-Si, a-Si, and the combined PV systems have been found to be approximately \(90.6,\) \(21.6\), \(8.7\), and \(10.3\text{ g}{\text{CO}}_{2}\), respectively.

-

13.

The mitigated \({\text{CO}}_{2}\) emission for the combined PV system during one year is equivalent to \(1.15\text{ cars}\) not used, \(2927.8\text{ L}\) of avoided gasoline, \(14.26\text{ barrels}\) of avoided crude oil, \(1.36\text{ acres}\) absorbed by forest, and \(2.14\text{ tons}\) of waste recycling.

In conclusion, based on the current findings, a-Si PV systems are highly recommended for tropical locations. Their superior array yield and significantly lower carbon footprint make them a preferable option over m-Si and p-Si PV systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Muteri, V. et al. Review on life cycle assessment of solar photovoltaic panels. Energies (Basel) 13 (2020).

Jathar, L. D. et al. Comprehensive review of environmental factors influencing the performance of photovoltaic panels: Concern over emissions at various phases throughout the lifecycle. Environ. Pollut. 326, 121474 (2023).

García-Valverde, R., Cherni, J. A. & Urbina, A. Life cycle analysis of organic photovoltaic technologies. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 18, 535–558 (2010).

Ballif, C., Haug, F.-J., Boccard, M., Verlinden, P. J. & Hahn, G. Status and perspectives of crystalline silicon photovoltaics in research and industry. Nat Rev Mater 7, 597–616 (2022).

Fthenakis, V. Sustainability of photovoltaics: The case for thin-film solar cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 2746–2750 (2009).

Irfan, M., Zhao, Z. & Ahmad, M. Processes A techno-economic analysis of off-grid solar PV system : A case study for Punjab Province in Pakistan. 1–14 (2019).

Imam, A. A., Al-turki, Y. A. & Kumar, R. S. Techno-Economic Feasibility Assessment of Grid-Connected PV Systems for Residential Buildings in Saudi Arabia—A Case Study Roughly. (2020).

Han, X., Garrison, J. & Hug, G. Techno-economic analysis of PV-battery systems in Switzerland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112028 (2022).

Abdul-ganiyu, S., Quansah, D. A., Ramde, E. W., Seidu, R. & Adaramola, S. Techno-economic analysis of solar photovoltaic ( PV ) and solar photovoltaic thermal ( PVT ) systems using exergy analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101520 (2021).

Ibrik, I. H. Techno-economic assessment of on-grid solar PV system in Palestine Techno-economic assessment of on-grid solar PV system in Palestine. Cogent. Eng. 7 (2020).

Tahri, F., Tahri, A. & Oozeki, T. Performance evaluation of grid-connected photovoltaic systems based on two photovoltaic module technologies under tropical climate conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 165, 244–252 (2018).

Farhoodnea, M., Mohamed, A., Khatib, T. & Elmenreich, W. Performance evaluation and characterization of a 3-kWp grid-connected photovoltaic system based on tropical field experimental results: New results and comparative study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 1047–1054 (2015).

Adouane, M., Al-Qattan, A., Alabdulrazzaq, B. & Fakhraldeen, A. Comparative performance evaluation of different photovoltaic modules technologies under Kuwait harsh climatic conditions. Energy Rep. 6, 2689–2696 (2020).

Sharma, R. & Goel, S. Performance analysis of a 11.2 kWp roof top grid-connected PV system in Eastern India. Energy Rep. 3, 76–84 (2017).

Shukla, A. K., Sudhakar, K. & Baredar, P. Simulation and performance analysis of 110 kWp grid-connected photovoltaic system for residential building in India: A comparative analysis of various PV technology. Energy Rep. 2, 82–88 (2016).

Akinyele, D. O., Rayudu, R. K. & Nair, N. K. C. Life cycle impact assessment of photovoltaic power generation from crystalline silicon-based solar modules in Nigeria. Renew. Energy 101, 537–549 (2017).

Lunardi, M. M. et al. A comparative life cycle assessment of chalcogenide/Si tandem solar modules. Energy 145, 700–709 (2018).

Luo, W. et al. A comparative life-cycle assessment of photovoltaic electricity generation in Singapore by multicrystalline silicon technologies. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 174, 157–162 (2018).

Yadav, S. K. & Bajpai, U. Performance evaluation of a rooftop solar photovoltaic power plant in Northern India. Energy Sustain. Dev. 43, 130–138 (2018).

Ramanan, P., K., K. M. & Karthick, A. Performance analysis and energy metrics of grid-connected photovoltaic systems. Energy Sustain. Dev. 52, 104–115 (2019).

Goswami, A. & Aizpurua, J. I. Reliability-aware techno-economic assessment of floating solar power systems. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 40, 101536 (2024).

Chang, Y.-M., Hsiao, Y.-T. & Tsai, K.-W. Unveiling the shadows: Overcoming bottlenecks in scaling organic photovoltaic technology from laboratory to industry. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400064 (2024).

Akhter, M. N., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H., Olatomiwa, L. & Muhammad, M. A. Performance assessment of three grid-connected photovoltaic systems with combined capacity of 6.575 kWp in Malaysia. J. Clean Prod. 277, 123242 (2020).

Ren, J. & Kan, Z. Photovoltaic Sustainability and Management. (AIP Publishing LLC, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1063/9780735423152.

Smith, B. L., Sekar, A., Mirletz, H., Heath, G. & Margolis, R. An Updated Life Cycle Assessment of Utility-Scale Solar Photovoltaic Systems Installed in the United States. www.nrel.gov/publications (2024).

Besseau, R. et al. An open-source parameterized life cycle model to assess the environmental performance of silicon-based photovoltaic systems. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 31, 908–920 (2023).

Caballa, L. G. C. & Recto, K. H. A. Sustainability analysis of residential photovoltaic systems: A life cycle assessment approach. In 2023 IEEE 15th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management, HNICEM 2023 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/HNICEM60674.2023.10589005.

Pimentel Pincelli, I., Hinkley, J. & Brent, A. Life cycle assessment of a virtual power plant: Evaluating the environmental performance of a system utilising solar photovoltaic generation and batteries. Renew. Energies 2 (2024).

Rus, T., Moldovan, R. P. & Pardo Picazo, M. Á. LCA analysis of a roof mounted PV system: A Romanian case study. Front. Environ. Sci. 12 (2024).

Lunardi , M.M., Dias , P.R., Deng , R. & Corkish, R. Life Cycle Environmental Assessment of Different Solar Photovoltaic Technologies (2021).

Almallahi, M. N. et al. Comparison between silicon and gallium solar cells for mini PV systems based on life cycle analysis. In 2023 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences, ASET 2023 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ASET56582.2023.10180708.

Quek, A. et al. Life cycle assessment of large-scale solar photovoltaic plant based in Malaysia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 1372 (Institute of Physics, 2024).

Al-Ugla, A. A., El-Shaarawi, M. A. I., Said, S. A. M. & Al-Qutub, A. M. Techno-economic analysis of solar-assisted air-conditioning systems for commercial buildings in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 1301–1310 (2016).

Shirazi, A., Taylor, R. A., Morrison, G. L. & White, S. D. A comprehensive, multi-objective optimization of solar-powered absorption chiller systems for air-conditioning applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 132, 281–306 (2017).

Bhandari, K. P., Collier, J. M., Ellingson, R. J. & Apul, D. S. Energy payback time (EPBT) and energy return on energy invested (EROI) of solar photovoltaic systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 47, 133–141 (2015).

Darling, S. B., You, F., Veselka, T. & Velosa, A. Assumptions and the levelized cost of energy for photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3133–3139 (2011).

Jeong, B., Jeon, H., Kim, S., Kim, J. & Zhou, P. Evaluation of the lifecycle environmental benefits of full battery powered ships: Comparative analysis of marine diesel and electricity. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8 (2020).

Khanmohammadi, S. & Khanmohammadi, S. Energy, exergy and exergo-environment analyses, and tri-objective optimization of a solar still desalination with different insulations. Energy 187, 115988 (2019).

Lau, K. Y., Tan, C. W. & Ching, K. Y. The implementation of grid-connected, residential rooftop photovoltaic systems under different load scenarios in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 316, 128389 (2021).

Akhter, M. N., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H., Olatomiwa, L. & Muhammad, M. A. Performance assessment of three grid-connected photovoltaic systems with combined capacity of 6.575 kWp in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123242 (2020).

Chow, T. T. & Ji, J. Environmental life-cycle analysis of hybrid solar photovoltaic/thermal systems for use in Hong Kong. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012 (2012).

Rajput, P., Malvoni, M., Kumar, N. M., Sastry, O. S. & Jayakumar, A. Operational performance and degradation influenced life cycle environmental-economic metrics of MC-Si, A-Si and hit photovoltaic arrays in hot semi-arid climates. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12 (2020).

Agrawal, B. & Tiwari, G. N. Building Integrated Photovoltaic Thermal Systems: For Sustainable Developments. Vol. 4 (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011).

Hassani, S., Saidur, R., Mekhilef, S. & Taylor, R. A. Environmental and exergy benefit of nanofluid-based hybrid PV/T systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 123, 431–444 (2016).

Lau, C. Y., Gan, C. K. & Tan, P. H. Evaluation of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of energy for PV grid parity analysis in Malaysia. Int. J. Renew. Energy Resour. 4(4), 28–34 (2014).

Laajimi, M. & Go, Y. I. Energy storage system design for large - scale solar PV in Malaysia : Techno - economic analysis. Renew. Wind Water Sol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40807-020-00064-5 (2021).

Azman, N. A. M., Abdullah, M. P., Hassan, M. Y., Said, D. M. & Hussin, F. Enhanced time of use electricity pricing for commercial customers in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 25, 285–294 (2017).

Hall, C. A. S., Balogh, S. & Murphy, D. J. R. What is the minimum EROI that a sustainable society must have?. Energies (Basel) 2, 25–47 (2009).

Guaita-Pradas, I. & Soucase, B. Endorse of renewable energy plants, still an alternative investment in Spain?. SOP Trans. Econ. Res. 1, 1–9 (2014).

Sreenath, S., Sudhakar, K. & Yusop, A. F. 7E analysis of a conceptual utility-scale land-based solar photovoltaic power plant. Energy 219, 119610 (2021).

Kato, K., Murata, A. & Sakuta, K. Energy pay-back time and life-cycle CO2 emission of residential PV power system with silicon PV module. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 6, 105–115 (1998).

Alsema, E. A., de Wild-Scholten, M. J. & Fthenakis, V. M. Environmental impacts of Pv electricity generation—A critical comparison of energy supply options. In The 21st European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Dresden, Germany. Vol. 7 (2006).

Fukurozaki, S. H., Zilles, R. & Sauer, I. L. Energy payback time and CO2 emissions of 1.2 kWp photovoltaic roof-top system in Brazil. Int. J. Smart Grid Clean Energy (2012).

Kim, B., Lee, J., Kim, K. & Hur, T. Evaluation of the environmental performance of sc-Si and mc-Si PV systems in Korea. Sol. Energy 99, 100–114 (2014).

Alsema, E. Energy payback time and CO2 emissions of PV systems. In Practical Handbook of Photovoltaics. 1097–1117 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385934-1.00037-4.

Ito, M. et al. A preliminary study on potential for very large-scale photovoltaic power generation (VLS-PV) system in the Gobi desert from economic and environmental viewpoints. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 75, 507–517 (2003).

Azzopardi, B. & Mutale, J. Life cycle analysis for future photovoltaic systems using hybrid solar cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14, 1130–1134 (2010).

Pacca, S., Sivaraman, D. & Keoleian, G. A. Parameters affecting the life cycle performance of PV technologies and systems. Energy Policy 35, 3316–3326 (2007).

Jungbluth, N., Dones, R. & Frischknecht, R. Life cycle assessment of photovoltaics: Update of the ecoinvent database. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1041, 33–42 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Abdelhak Lekbir: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing — original draft. Samir Hassani: methodology, formal analysis, writing — original draft. Putri Nor Liyana: formal analysis, writing—original draft. Saad Mekhilef: conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, project administration. Kok Soon Tey: Writing—review and editing, supervision; Abdullahi Mohamed Samatar: Methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; Obaid Alshammari: writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lekbir, A., Hassani, S., Mohamad Radzi, P.N.L. et al. Comprehensive investigation of rooftop photovoltaic power plants with monocrystalline polycrystalline and thin-film technologies for exergy economic and environmental assessments. Sci Rep 15, 15517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99939-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99939-0