Abstract

Single-component thermal conductive silica gel (S-TCSG) is a new type of thermal conductive material for packaging electronic components in high-performance printed circuit boards. Its mechanical properties can lead to excessive deformation of printed circuit boards or even solder joint fracture during screw fastening or falling. In this paper, an experimental program was developed to study the mechanical properties of the S-TCSG, such as cushioning property, creep and stress relaxation. The relationship model is established between cushioning coefficient, compression stress and compression strain on the basis of the compression stress-strain test. In addition, the time-varying laws of the compression creep and stress relaxation of the S-TCSG were studied experimentally. The elastic modulus, relaxation modulus and creep compliance can be obtained based on the experimental data. A nonlinear finite element model (FEM) of the S-TCSG is established. Furthermore, the influence of gel thickness on stress distribution is analyzed in screw tightening. A mathematical model is proposed to characterize the relationship between gel thickness, compressive stress and displacement load. This study is of great practical significance to the rationality of coating thickness of the S-TCSG and the performance improvement of printed circuit boards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-component thermal conductive silica gel (S-TCSG) has the properties of low stress, high thermal conductivity and strong bonding. It is a new type of heat conductive material for heat dissipation of heating elements in electronic products. The printed circuit boards (PCB for short) are widely used in various electronic products as the carriers for electronic components and their electrical connections. To improve the thermal conductivity and shock resistance of electronic products, the highly integrated PCB are connected to the substrate coated with the S-TCSG by screws. However, screw fastening or product drop can lead to excessive deformation for PCB or even fracture for solder joints. It’s caused by the influence of mechanical properties such as cushioning, creep and stress relaxation of the S-TCSG. Based on the Web of Science database retrieval, the preparation process and thermal conductivity of the S-TCSG have been studied by scholars. The mechanical property characterization and the influence rule of physical parameters in bolted joints have not yet been proposed. Therefore, it is necessary to study the mechanical properties of the S-TCSG.

The S-TCSG is a kind of polymer material. Its creep and stress relaxation can be studied by using the existing analysis methods of mechanical properties of polymer materials. In terms of creep, it was pointed out by Barbero and Luciano that the structural properties are seriously affected by the creep and stress relaxation responses of polymer matrix composites in long-term service1. Soliman et al. studied the shear creep behavior of reinforced EP nanocomposites. Their creep properties are calculated and analyzed by using Rose model and improved Maxwell model2. It was experimentally investigated by Naresh et al. that the effects of isothermal temperature, compaction speed and pressure on compaction creep of cured glass/epoxy prepreg3. They pointed out that the percentage of compaction creep increases with compaction speed and pressure. It first increases and then decreases with the increase of temperature. Chang et al. studied the effect of xanthan gum on the creep of protein emulsion gel. They pointed out that the system containing polysaccharides shows lower deformation4. Brito-Oliveira et al. studied the creep properties of protein emulsion gels, protein emulsion gels with xanthan gum and protein emulsion gels with locust bean gum by AR2000 rheometer5. The results showed that the polysaccharide composition under constant stress 5 MPa is helpful to improve the gel strength and reduce the creep flexibility. Kodaira et al. studied the multiaxial creep deformation behavior of porous polymer membranes by small punch tests6. It was pointed out that the nonlinear tensile creep behavior is significantly dependent on the level of holding stress at room temperature. Al Jahwari and Naguib proposed an analysis method of creep flexibility based on linear viscoelastic model and three-dimensional finite element method7. This method was used to predict the creep behavior of polymer hollow composites. The creep tests were performed by Instron Micro tester 5848. In recent years, digital speckle correlation method (DSCM) has been widely used in creep tests of anisotropic materials8,9,10,11. Wu et al. experimentally studied the creep properties of self-reinforced polyethylene terephthalate based on this method12. Spathis and Kontou theoretically investigated the viscoelasticity under small strain and the viscoplasticity under higher stress during creep of polymeric materials13. Lai and Bakker studied the effect of ambient stress levels at room temperature on the creep deformation of high-density polyethylene based on tensile creep tests14. The aforementioned literature has been analyzed. The short-term creep experiments have been found to be the most common. The reason is that long-term creep experiments are very expensive and time-consuming. In addition, it has been pointed out in existing studies that stress, temperature and time are the key factors affecting the creep behavior of polymer materials. A method based on short-term creep experimental data and time-temperature-stress superposition principle was proposed14,15,16,17,18. It aims to accurately predict the long-term creep behavior of polymer materials in practical application. However, the creep behavior of the S-TCSG has not been studied in detail.

In terms of stress relaxation, Meera et al. studied the tensile stress relaxation behavior of natural rubber filled with TiO2 and nano-SiO2 by Tinius-Olsen testing machine19. Fernandes and De Focatiis used Instron 5969 tensile testing machine to perform uniaxial tensile tests on filled rubber at room temperature. They also analyzed the influence of deformation history on stress relaxation20. Obaid et al. used TAQ800 dynamic mechanical analyzer to measure the stress relaxation behavior of glass fiber reinforced polypropylene composites at 30 ℃21. The results showed that the stress relaxation behavior of short fiber composites can be explained by combining transient shear stress transfer at the fiber-matrix interface. Based on the Instron 1195 universal testing machine, Bhagawan et al. explored the effect of stress level, fiber orientation and temperature on the stress relaxation rate of short-jute-fiber-reinforced acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber under tension. It was able to report that the stress relaxation process within 200 s is divided into two modes22. An experimental method was proposed by Yang et al. combining edge detection with closed-loop proportional integral-differential control. The nonlinear creep and stress relaxation characteristics of collagen fibers were studied at room temperature. The data was processed applied the adaptive quasi-linear viscoelastic model proposed by Nekouzadeh et al.23,24,25. It was realized by Oman and Nagode that both creep and relaxation come from the same viscoelastic mechanism. They are able to be predicted from each other26. Luo et al. introduced a time-dependent damage function. An engineering method was established to describe the mapping relationship between rubber creep and stress relaxation. The effectiveness of the method was verified by dumbbell specimens18. With the development of finite element technology, Abaqus has been used to predict the stress relaxation and creep response of reinforced polymer matrix composites27. Jeya et al. studied the creep relaxation behavior of high-density polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride. It was combined with experimental and numerical simulation methods28. Yue et al. developed a dual-scale three-dimensional thermos-viscoelastic model to accurately predict the structural deformation of thermoplastic composite laminates during hot stamping29. Meddahid et al. proposed and rigorously analyze a semi- and fully discrete discontinuous Galerkin method in terms of elastic and viscoelastic stress components and with mixed boundary conditions30. Yun et al. Introduced a novel methodology for predicting the lifetime and the sealing performance of nonmetallic materials exposed to downhole environments31. Lefevre et al. introduced an Abaqus UMAT subroutine for a family of constitutive models for the viscoelastic response of isotropic elastomers of any compressibility undergoing finite deformations32. Brandt et al. presented that hyperelasticity is formulated using Ogden’s model when nonlinear elasticity is considered by studying a Hooke-like linear relationship between different pairs of nonlinear measures of stress and strain33. Harald et al. presented a parametric finite element approximation of two-phase Navier–Stokes flow with viscoelasticity34. Wei et al. proposed a high-performance thermal pad with diphase continuous structure reinforced by liquid metal. The findings indicate that the composite exhibits favorable insulation performance, mechanical characteristics, and a thermal conductivity of up to 12.41 W/(m K)35. However, the nonlinear behavior characterization model for creep and buffering behavior of the S-TCSG in screw fastening has not been proposed. In addition, the stress relaxation of the S-TCSG in bolted joints is also crucial to the research on the uniform distribution of bolt preload.

The existing literature indicates that theoretical modeling, numerical simulation and experimental research are the basic methods to study the mechanical properties of polymer materials. The loading rate, load level and material thickness have important influence on the compressive mechanical properties of materials. The complexity of theory analysis and the time-dependent uncertainty of mechanical properties are considered for the S-TCSG in this paper. The method combining experiment with simulation is applied, and quantified the stress-strain, creep and stress relaxation of the S-TCSG under compression. In this paper, the stress-strain experiment was carried out at first. The model of material buffer coefficient is established based on the experimental data. Secondly, the creep and relaxation behavior of the S-TCSG were studied experimentally. On this basis, it’s combined with numerical simulation. The viscoelastic analysis model of the S-TCSG is established. Finally, the stress model and stress range function of thermally conductive silica gel under different loads are given. The feasibility of the theoretical model is verified.

Design of experiments

Problem statement

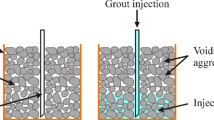

The heat is generating by components such as graphics processing unit (GPU) and central processing unit (CPU) during the operation of electronic products. It is one of the main reasons that limit the highly integrated and extreme development of printed circuit boards. For this reason, when the PCB and the substrate are assembled by screws, a certain thickness of the S-TCSG is often coated between the heating element and the substrate. Considering the room temperature assembly environment and maneuverability, the gel is required to have weak fluidity.

One-component thermal conductive silicone gel belongs to room temperature curing organic silicone rubber. It has become a widely used thermal conductive material in electronic industry. Its main components are organosilicon and polymer materials. In the process of use, the high-performance elastomer is vulcanized based on condensation reaction. The good heat dissipation performance of the printed circuit board is ensured. In addition, the model of the S-TCSG studied in this paper is BN-TG350-6, which has the following advantages:

(1) Low requirements for interface geometry;

(2) Pre cured, easy to use;

(3) Has certain wetting performance, ultra-low contact thermal resistance, and can quickly dissipate heat;

(4) Good compressibility, capable of compressing up to 0.1 mm;

(5) Ultra low compressive stress, no stress damage to components;

The structure of current electronic products is analyzed. The position relationship between printed circuit board, matrix and the S-TCSG is clarified, as shown in Fig. 1. The printed circuit boards sealed with CPU is connected with the substrate through screws. The surface of CPU is bonded to the S-TCSG on the base. In order to ensure the tight fit, the S-TCSG is subjected to partial pressure. According to Newton’s third law, it is not difficult to understand that the strain of the PCB subjected to the reaction force may exceed the threshold requirement and increase the scrap rate.

Samples and experimental equipment

Based on the above analysis, the mechanical properties of the S-TCSG were studied based on experiments. The simples mold large enough are used to make the samples of the S-TCSG. The samples meet the experimental requirements. They are made at the same time. The purpose is to ensure the consistency of the physical properties of the samples. The samples are made into two specifications: 25 mm*25 mm and 10 mm*10 mm. The manufacturer’s suggestion is considered. The thickness of this kind of gel does not exceed 6 mm. In order to study the effect of gel thickness on mechanical properties, 4 mm and 8 mm were selected.

The compression test is carried out using the electronic tension tester (CMT4304) shown in Fig. 2. The load capacity is 20kN. The load accuracy is ± 0.5% of the displayed value. A cylindrical loading device is manufactured for compressing gel samples. Based on the stress-strain curve of the S-TCSG, the buffer coefficient and elastic modulus are calculated. In addition, creep and stress relaxation are studied experimentally. It provides data and parameter support for finite element analysis.

Mechanical property experiment

The repeated tests of quasi-static compression were carried out at room temperature. After eliminating the gross error, the average engineering stress-strain curve is taken as the research object. According to the slope of the curve, the stress-strain curve of the gel under quasi-static compression is divided into three stages: (i) elastic stage, (ii) plastic stage, and (iii) densification stage36. Therefore, the mechanical properties of thermally conductive silica gel have been investigated.

Stress-strain curve

The thickness of the S-TCSG is 25 mm*25 mm*4 mm. The quasi-static compression test of the S-TCSG was carried out at the compression rate of 1 mm/min. The stress-strain curve was obtained by processing the test data as shown in Fig. 3a. As shown in Fig. 3b, the strain values of 6.25% and 58.75% are the dividing points of the three stages of the stress-strain curve. These three stages reflect the compressive properties of the gel. When the strain is less than 6.25%, the relationship between stress and strain is linear. The calculated elastic modulus E of the S-TCSG is 0.32 MPa. The specific stiffness (E/ρ) is about 94.12 N·m·kg−1. These indicate that the S-TCSG has good compressibility and high plasticity. With the continuous increase of strain, plastic deformation occurred for the S-TCSG. The deformation was not recovered after unloading, i.e., irreversible deformation. Beyond the 58.75% strain, the structure was densified and completely damaged. At a 60% strain, the stress reached 0.24 MPa. The results (ρ, E, σc) are normalized for the mechanical properties of ordinary silica gel (ρS = 1.3 g∙cm−3, ES = 1.2 GPa). By analyzing the sample density function of data points, the scaling laws of the mechanical properties of the S-TCSG are determined as:

where σc is the compressive strength at a strain of 60%. E and ρ represent the elastic modulus and density of the S-TCSG respectively. ES and ρS are respectively the elastic modulus and density of ordinary silica gel.

After calculation, the slope of the Eq. (1) is u ≈ 0.417 for the S-TCSG in the elastic stage. It shows that when the density of the S-TCSG increases by 1% point, the elastic modulus increases by 0.417% on average. Under 60% strain, the slope of Eq. (2) is v ≈ 0.417 for the S-TCSG. In other words, when the density of the S-TCSG increases by 1% point, the stress will increase by an average of 0.417%.

On this basis, the S-TCSG with thickness 25 mm*25 mm*8 mm is selected for quasi-static compression tests. The compression rates is respectively 10 mm/min and 5 mm/min. The average stress-strain curve is shown in Fig. 4. It is affected by the factors such as gel thickness and compression rate. The stage division point of the stress-strain curve changes. It is mainly manifested as the lengthening of the elastic phase. The load achieved during the densification phase becomes larger. Figure 4a and b are respectively quasi-static compression tests with compression rates of 10 mm/min. The results show that there is a linear relationship between stress and strain when the strain is less than 13.75%. The calculated elastic modulus E of the S-TCSG is about 0.16 MPa. The specific stiffness (E/ρ) is about 47 N·m·kg−1. Figure 4c and d are respectively the results of quasi-static compression tests with compression rates of 5 mm/min. The elastic stage occurs in a strain range of less than 17.5%, and the elastic modulus is about 0.14 MPa. At both rates, the structure is densified and completely damaged when the strain exceeds 58.75%. It can be seen that increasing the compression rate may enhance the ability of the material to resist deformation when the thickness of the gel is constant.

Compression properties of the S-TCSG with thickness of 8 mm (a) the load-displacement relationship under the compression rate of 10 mm/min; (b) the engineering stress curve under the compression rate of 10 mm/min; (c) the load-displacement relationship under the compression rate of 5 mm/min; (d) the engineering stress curve under the compression rate of 5 mm/min.

According to the above test conditions, a comparative test of 40%, 50% and 60% compression was set. The results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Through experimental analysis, the compression rate is increased from 5 mm/min to 10 mm/min for the same specification of the S-TCSG. The compressive strength under 40% strain increased by 35.2%. The compressive strength under 50% strain increased by 39.1%. The compressive strength under 60% strain decreased by 37.2%. This indicates that excessive compression rate will lead to the decrease of compression strength. It also makes the material fracture or yield prematurely. At the same time, the compression rate increases from 1 mm/min to 10 mm/min. Thickening gel is conducive to the improvement of compressive strength when there is the possibility of material failure. So then, the effect of delaying material failure is achieved.

Creep effect

Creep is a phenomenon that the strain of solid materials increases with time under the condition of constant stress. The two specifications of the S-TCSG are selected at room temperature, such as 10 mm*10 mm*4 mm and 10 mm*10 mm*8 mm. The 120 min creep test was carried out under different load levels. The load level is shown in Table 3.

Different load levels are uniformly applied to the whole surface of the sample. The corresponding displacement and load are collected at a specified time. The stress-strain curve is drawn, as shown in Fig. 5. With the increase of strain level, the creep stress changes from linear growth to non-linear growth, until to the stress balance.

According to the strain ε=((x-x0)/x0) × 100%, the strain value is calculated and the creep curve is made, as shown in Fig. 6. As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the yield stress of the gel material is related to the initial load and gel thickness. The yield stress is within 0.2% strain range for these two-specifications gel. The ultimate stress increases with the initial load level for the specimen with thickness 4 mm. The tensile strength is 0.2689 MPa. The maximum strain is 1.385%, and the corresponding time is 1.4262 h. Similarly, the ultimate stress no longer obeys this law for the 8 mm specimen. The creep stress increases slowly with the strain in the yield stage. The tensile strength is 0.5854 MPa. Its strain is 1.465%, and the corresponding time is 0.024 h. Compared with the stress-strain curve of tensile strength, the elasticity retention is higher for low-thickness specimens. The yield stage is longer. From the creep curve, it is known that the creep strain increases with time and the initial load level.

Creep deformation is one of the main forms of creep failure. According to the analysis of creep rate, the creep goes through acceleration period, deceleration period and steady period in the test time for the S-TCSG. The creep rate decreases to a stable value with the increase of time. It is found that the deformation failure may occur caused by the sharp increase of creep rate in the steady state, if the initial load level is too high. It is worth noting that only the normal service of the gel is considered here. Therefore, the creep law is fitted for the S-TCSG under different load levels from the data of Fig. 6. It is expressed as:

where ε is the strain percentage. t is the creep time (unit: s). e is the natural index. The rest are parameter constants. As a result, the variation of creep rate with time is characterized as:

In addition, the creep compliance can be derived from the Eq. (5) and J(t)= ε(t)/σ0, where σ0is the stress constant under a given strain37. Take the gel with thickness 4 mm as an example. The creep curve fitted according to Eq. (3) is very close to that of the test, as shown in Fig. 7. In fact, the creep curve is also consistent with Eq. (3) for the gel with thickness 8 mm. According to the coefficient of determination (5), the goodness of fit is about in the interval [0.8, 1]. The creep law can be approximately expressed by Eq. (3) for the S-TCSG during the test time.

where εi is the true value of creep. \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the fitting value of creep.

Stress relaxation

Under different strain levels, the initial length and width of the test samples are 10 mm. The stress relaxation test was carried out at room temperature. The sample was parked for 30 min. The load-time curve obtained by recording the data is shown in Fig. 8. At the initial moment, the compression load of the S-TCSG decreases rapidly. Its value decreases continuously with the increase of time, and finally tends to be stable. The load-time curves under the different initial thickness are compared. When the residual thickness is 0.6 mm, the sample with large initial thickness enters the stable state earlier. The elastoplastic duration is shorter. When the residual thickness is greater than or equal to 0.75 mm, the sample with small initial thickness is easier to enter the stable state. The elastoplastic duration is longer.

Using the force values at 30 min and 0 min, the compressive stress relaxation is calculated according to GB/T1685-2008, as shown in Fig. 9. The relaxation has reached stability at 30 min for the gel sample with the thickness of 4 mm. But under the same condition, the relaxation can’t be completely stable for the gel sample with the thickness of 8 mm. The gel sample in compression thickness with residual 0.9 mm is the most obvious.

At the same time, the percentage of compressive stress relaxation is shown in Table 4. The larger the remaining thickness is, the greater the compression stress relaxation rate is. This is because that the S-TCSG has relatively greater elasticity. The material with large residual thickness obviously tends to return to its original state at the initial time of relaxation test. The stress relaxation amplitude is also larger. Therefore, the remaining thickness is reduced. The elasticity of the material is suppressed. The plasticity and viscosity play a major role. The compressive stress relaxation rate will also be reduced. These are the reasons that the stress level of the S-TCSG reaches a stable state as soon as possible.

Based on the Eq. (6), the relaxation modulus is obtained from G(t)= σ(t)/ε0. Here ε0is the strain constant under a given stress30. On the other hand, the stress relaxation rate is

The goodness of fit is about 0.975 for the relaxation model. The change regularities of stress relaxation of the S-TCSG are highly explained. It’s not going to be repeated here.

The greater the relaxation rate is, the easier it is to cause sudden stress relaxation failure. Relatively, the smaller the relaxation rate is, the smaller the rate of the S-TCSG from elastic deformation to plastic deformation is. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a relaxation rate model in theory to facilitate the judgment of stress relaxation in practical engineering.

Cushioning property

The materials with better cushioning properties are rubber, latex, EVA and so on. They have the characteristics of absorption, recovery, adaptation and environmental protection. Because of the unique preparation component for the S-TCSG, it has viscoelastic plasticity. The stress load is obtained during the assembly of bolts or service. In this process, it gives full play to the buffering and vibration isolation effect of the S-TCSG. The possibility of chip failure is reduced.

Cushioning coefficient is a parameter to describe the properties of cushioning materials. It is equal to the reciprocal of buffer efficiency. In general, the basic steps for determining the buffer coefficient C and drawing the C-σ curve are as follows:

(1) Point segmentation: j interval points σi (i = 1, 2, …, j) are taken according to stress. The area under the stress-strain curve is divided into several subregions;

(2) Solution of stress and strain: according to the stress-strain curve, the stress σi and strain εi (i = 1, 2, …, j) are calculated;

(3) Determine the increment of deformation energy: the increment of deformation energy is calculated for each stress region, that is, the area of each sub-region is solved ∆ui=0.5×(σi + σi−1)(εi-εi−1);

(4) Calculating the deformation energy: the deformation energy corresponding to stress σi is calculated, that is ui =∑∆uk (k = 1, 2, …, i);

(5) Solving the buffer coefficient: the buffer coefficient Ci corresponding to stress σi is calculated.

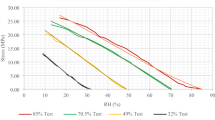

The loading equipment is the compression tester mentioned above for the static test of the buffer material. The loading speeds are set as 1 mm/min, 5 mm/min and 10 mm/min. That is close to the static load. The buffer coefficient corresponding to each stress is determined according to the calculation steps of the buffer coefficient. Then, under the action of 60% strain, the buffer coefficient-compression stress curve and the buffer coefficient-compression strain curve are shown in Fig. 10 for the S-TCSG with thickness 4 mm. As can be seen from Fig. 10a, the buffer coefficient decreases rapidly with the increase of compression stress, when the compression rate is 1 mm/min. After reaching the minimum value, the buffer coefficient no longer changes rapidly with the increase of compression stress, but gradually tends to a steady. From the Fig. 10b, the minimum buffer coefficient is about 4.52173913. The corresponding strain is about 0.35. That σ = 0.0416 MPa is obtained by looking for the stress-strain curve (see Fig. 3b). This is consistent with the result of cushioning coefficient-compressive stress curve in Fig. 10a. Assume that T is the pattern thickness. H is the maximum allowable drop height of the product. G is the maximum impact acceleration of the product. W is the product quality. A is the buffer area. σmax is the maximum stress. The cushioning material is redesigned by T = CH/G and A = WG/σmax. The best cushioning design is obtained.

Furthermore, the relationship for buffer coefficient-compression stress and buffer coefficient-compression strain were tested for the thermally conductive silica gel with the same thickness at different compression rates. It is discussed at the compression rate in 5 mm/min or 10 mm/min in the elastic stage. The buffer coefficient decreases rapidly with the increase of compression stress. It decreases slightly with the decrease of compression strain, as shown in Fig. 11. Under the condition of the same thickness, the compression rate increases from 5 mm/min to 10 mm/min. The stress increases by 0.028 MPa and the strain increases by 0.15. The minimum buffer coefficient is reduced by 55.2344%. It means that it is more reasonable to compress the S-TCSG of 8 mm with the loading rate of 10 mm/min. In other words, the material per unit thickness absorbs more impact energy under the same cushioning effect or the same load. The cushioning performance is better. The protection effect on the chip is better.

According to the above analysis, the relationships between cushioning coefficient, compressive stress and compressive strain are expressed as Eqs. (8) and (9) by third-order Gaussian model.

In the formula, σi is the point stress. Ci is the cushioning coefficient corresponding to the point stress. Other parameters are shown in Table 5.

In the formula, εi is the point strain. Ci is the cushioning coefficient corresponding to the point strain. Other parameters are shown in Table 6.

The buffer coefficient is affected by various factors such as energy, density, deformation, force and so on. The numerical reference is provided for the buffer design and material properties of the S-TCSG by the study of the relationship between buffer coefficient, stress and strain. It also improves the protection ability of the chip.

Stress simulation analysis and modeling

Establishment of finite element model

In order to analyze the viscoelastic behavior of the S-TCSG, Prony series was used to define its viscoelasticity38,39. According to the above experimental analysis, the elastic modulus, relaxation modulus and creep compliance of the S-TCSG are determined. The parameter mi=Ei/E0 is introduced. E0 and Ei are calculated by Eq. (3) to determine mi. The Prony parameter τi is obtained from Eqs. (3) and (4) in combination with the modulus parameters of the S-TCSG. In addition, Poisson’s ratio is determined by the relationship between elastic modulus and relaxation modulus. The viscoelastic property of the material is set. The local coordinate system is defined. The solid model is meshed with hexahedral elements. The mesh type is C3D8R stress element, as shown in Fig. 12. The grid density is very fine. Furthermore, constraints are applied to the surrounding and lower surfaces of the solid model to approximate the actual working conditions. By utilizing software repair functions in key areas, the sharp corners at the interface have been changed to small rounded corners to avoid theoretical singularities. The Z displacement load is applied to the upper surface. The translation degree of freedom is constrained to of the lower surface simulate the tension or compression of the gel. In the process of compression, each stress element is subjected to normal force and shear force to ensure the force balance of the element.

where τi is the relaxation time, Ei is the corresponding relaxation modulus, and E∞ represents the equilibrium modulus.

Stress simulation analysis

The S-TCSG of 10 mm*10 mm*4 mm is taken as the research object. The compression displacement load of 3.25 mm is applied to the surface. From the overall Von Mises stress state in Fig. 13, the total stress is mainly tensile force. The maximum stress region is at the four corners of the lower surface. Its value is 0.3889 MPa. The stress in most areas is at 0.1015 MPa ~ 0.2213 MPa.

Figure 14 is a cross-sectional view of the X-plane. The stress distribution is symmetrical with respect to the X-plane. Zone A is mainly subjected to tensile force, while Zone B and Zone C are mainly subjected to compression force. The maximum tensile force is 0.01925 MPa. The maximum compression force is 0.1182 MPa. The tensile force linearly decreases. The compressive force linearly increases.

The stress distribution in the Y direction is symmetrical with respect to the Y-plane. The stress distribution is the same as that in the X direction. The Z direction is only subjected to compression force, as shown in Fig. 15. The compression force decreases linearly and then increases linearly. If a point in Zone D is selected, the stress-strain relationship is also linear. The stress increases with strain.

Furthermore, in the direction of the XY-plane, the maximum tensile stress and the maximum compressive stress are on the upper surface of the gel. One points in the two ultimate area are successively collected to draw the stress-strain curve, as shown in Fig. 16. The maximum tensile region and the maximum compressive stress region are distributed diagonally symmetrically. At the maximum tensile stress point or the maximum compression stress point, the shear stress increases with strain. The stress distribution is symmetrical with respect to the center of the upper surface. In addition, the maximum principal stress is dominated by compressive stress. The minimum value is −0.06223 MPa. The minimum principal stress is compressive stress. The minimum value is −0.4569 MPa. The equivalent compressive stress is between 0.03385 MPa and 0.1981 MPa. That is, the gel resists the compression deformation of the material by a maximum tensile force of 19.81 N during compression. The instantaneous force at the maximum compression displacement is very close to the initial compression force of 20.4 N. This initial compression force is obtained in the relaxation test of the same sample with the residual thickness 0.75 mm. This also shows that the finite element model is reasonable.

Next, the effects of gel thickness and initial load on the stress distribution of the S-TCSG will be studied. Firstly, the stress distribution is be analyzed for the specimen with a thickness of 50 μm under the initial load of 81.25%, as shown in Fig. 17. The maximum compressive stress is 0.1274 MPa. The range of compressive stress is 0.05179 MPa. At the same load level, the maximum compressive stress is 0.1425 MPa for the specimen with thickness of 1 mm. The range of compressive stress is 0.1141 MPa.

In the same way, a displacement load is applied to the upper surface of the S-TCSG with thickness of 1 mm. In the initial load of 81.25%, the compressive stress increases linearly with the gel thickness. It increases exponentially with the compression displacement, as shown in Fig. 18. The growth rate of the maximum compressive stress is higher than that of the minimum compressive stress.

In the range of thickness 1 mm to 4 mm, the minimum compressive stress finally tends to a steady state with the increase of compression displacement. While the maximum compressive stress continues to increase. According to the stress cloud map, the most dangerous area is at the four edges of the lower surface. Especially, the four corner regions of the gel with thickness of 1 mm are obviously deformed. The equivalent compressive stress of gel with different thickness was collected in different displacement load. The relationship between gel thickness, compressive stress and displacement load was fitted as Eq. (11).

In the formula, σ represents the equivalent compressive stress. x is the gel thickness. h is the compression displacement.

The function of stress range of thermally conductive silica gel is

Verification and discussion

The compressive stress range curve is drawn for the specimen with a thickness of 50 μm to 4 mm under the initial load of 81.25%, as shown in Fig. 19. At the same load level, the dispersion of compressive stress of the specimen increases with the thickness. When the thickness is at [50 μm, 1 mm], the error interval of the stress range function between the simulation results and the experimental data is [0.0041, 0.00979]. It shows that too thin gel is more likely to cause uneven stress distribution on the PCB surface, and more likely to cause assembly failure. The finite element model proposed in this article can be used to estimate the uniformity of the overall stress distribution when the thickness is very small. When the thickness is equal to 4 mm, the error between the simulation results and the experimental data is 0.00001. It indicates that the finite element model can simulate the mechanical properties of the 4 mm gel. Overall, the stress range function is highly correlated between the simulation model, the theoretical model and experimental result under different thickness. It is calculated that the stress distribution of the S-TCSG is characterized by the theoretical model (11). The theoretical model (12) is used to measure the measures of dispersion of stress under different thickness.

The relationship between maximum compressive stress and thickness was analyzed for different compression ratios, as shown in Fig. 20. When the compression ratio is constant, the maximum compressive stress increases with the increase of gel thickness. When the thickness is greater than 4 mm, the growth rate of maximum compressive stress significantly decreases. The smaller the compression ratio, the more sensitive the effect of thickness on compressive stress.

The distribution uniformity and maximum stress for surface stress of PCB are comprehensively considered during assembly. It is known from Figs. 19 and 20that the confidence interval of thickness for the S-TCSG is1,4. Within this interval, the confidence interval of stress under a certain compression ratio can be calculated, and the stress range function can be used to determine the uniformity of stress distribution. Since the excessive compression ratio will lead to serious deformation of the S-TCSG, it is assumed that the compression ratio is 81.25%. The relationship between the thickness of the S-TCSG and the compression stress is drawn according to the model (11), as shown in Fig. 21. The results indicate that the minimum compressive stress is about 0.3 MPa. The confidence interval of the maximum stress is [0.13,0.2] for the S-TCSG with a thickness of 1 mm to 4 mm. The confidence intervals for the stress range function are [0.1,0.17]. This provides range of initial preload for controlling the assembly of PCB in practice.

Consequently, according to the heat dissipation requirements, the thinner the gel is, the faster the heat dissipation is. But the too thin gel can’t play a good physical protection effect on the chip. The gel thickness and stress dispersion are taken into account. Combined with the mechanical properties of the chip and the gel, the compressive stress model is proposed in this paper. It provides a theoretical reference for determining the uniformity of the stress distribution of the chip on the PCB, and the thickness of the S-TCSG in contact with the chip. The mechanical service performance of the chip is better ensured as a whole.

Conclusion

PCB are widely used as the carriers for electronic components and their electrical connections. In this paper, the problem of stress distribution of the S-TCSG is studied, caused by pre-tightening force assembly of PCB. The finite element analysis of viscoelasticity of the S-TCSG is carried out based on mechanical property tests. The stress dispersion evaluation model about gel thickness and compression displacement is proposed. The time effect is considered during tightening the screws in the prescribed order. The buffering properties, creep and stress relaxation of the gel samples are analyzed. According to the material properties determined by the experiment, the finite element model is established. The stress of the S-TCSG with different thickness is analyzed in different directions. The evaluation model of compressive stress is put forward, related to the gel thickness and displacement load. It aims to evaluate the stress distribution of the chip contact surface and the gel. The main results are as follows:

(1) The creep deformation and stress relaxation models are established. The goodness of fit is at the interval [0.8, 1]. It is indicate that tthe yield stress of the gel material is related to the initial load level and gel thickness. The elasticity retention is higher for low thickness specimens. The yield stage is longer. The deformation failure caused by the sharp increase of creep rate may occur after the steady state, if the initial load level is too high.

(2) The goodness of fit is about 0.975 for the relaxation model, which explains the change regularities of stress relaxation of the S-TCSG. The stress level of the S-TCSG reaches a stable state as soon as possible, which reasons is that the remaining thickness is reduced and the elasticity of the material is suppressed. The plasticity and viscosity play a major role. The compressive stress relaxation rate will also be reduced. This is vital to accurately facilitate the judgment of stress relaxation in practical engineering.

(3) A relationship between buffer coefficient, compressive stress and compressive strain is proposed for the S-TCSG. The material per unit thickness absorbs more impact energy at constant load. The cushioning performance is better. The protection effect on the chip is more prominent. The numerical reference is provided for the buffer design and material properties of the S-TCSG.

(4) In the XY direction, the shear stress increases with strain. The stress distribution is symmetrical with respect to the center of the upper surface. The maximum stress region is in the four corners of the lower surface. It’s the maximum compression point. The gel resists the compression deformation of the material by a maximum tensile force of 19.81 N during compression. The instantaneous force at the maximum compression displacement is very close to the initial compression force of 20.4 N. This provides a theoretical reference for the selection of initial loads.

(5) The stress model is proposed, related to gel thickness and displacement load. The stress range function is derived. It characterizes the state of stress distribution in theory. When the compression ratio is constant, the maximum compressive stress increases with the increase of gel thickness. The confidence interval of the maximum stress is [0.13,0.2] for the S-TCSG with a thickness of 1 mm to 4 mm. The confidence intervals for the stress range function are [0.1,0.17]. It provides a theoretical reference for determining the uniformity of the stress distribution of the chip on the PCB, and the thickness of the S-TCSG in contact with the chip.

In a word, data support is provided for the improvement of the parameter database of finite element analysis of the S-TCSG by the study of mechanical properties. The theoretical guidance is provided for the actual smear thickness of the S-TCSG and the magnitude of the initial load by the stress model and evaluation model proposed in this paper.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Abbreviations

- u,v:

-

the slope in the elastic stage

- E:

-

the elastic modulus of the S-TCSG

- ε:

-

the strain percentage

- ES :

-

the elastic modulus of ordinary silica gel

- x0 :

-

the initial thickness of gel

- Ei :

-

the corresponding relaxation modulus

- x:

-

the gel thickness

- E∞ :

-

the equilibrium modulus

- t:

-

the time (unit: s)

- σmax :

-

the maximum stress

- H:

-

the maximum allowable drop height of the product

- σmin :

-

the minimum stress

- G:

-

the maximum impact acceleration of the product

- σr :

-

the function of stress

- W:

-

the product quality

- σc :

-

the compressive strength

- A:

-

the buffer area

- σ0 :

-

the stress constant under a given strain

- R2 :

-

the goodness of fit

- σ:

-

the compressive stress

- e:

-

the natural index

- J(t):

-

the creep compliance

- ε0 :

-

the strain constant under a given stress

- G(t):

-

the relaxation modulus

- εi :

-

the true value of creep; the point strain

- ρS :

-

the density of ordinary silica gel

- \(\epsilon_{i}^{'}\) :

-

the fitting value of creep

- ρ:

-

the density of the S-TCSG

- \({v_\sigma }(t)\) :

-

the stress relaxation rate

- τi :

-

the relaxation time

- \({v_\varepsilon }(t)\) :

-

the variation of creep rate

- X:

-

x-axis

- ai,bi,ci,di,i=0,1,2,3,4:

-

the parameters

- Y:

-

y-axis

- Ci :

-

the cushioning coefficient

- Z:

-

z-axis

- h:

-

the compression displacement

References

Barbero, E. J. & Luciano, R. Micromechanical formulas for the relaxation tensor of linear viscoelastic composites with transversely isotropic fibers. Int. J. Solids Struct. 32 (13), 1859–1872 (1995).

Soliman, E., Kandil, U. F. & Taha, M. R. Limiting shear creep of epoxy adhesive at the FRP–concrete interface using multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Adhes. Adhe. 33, 36–44 (2012).

Naresh, K. et al. Rate and temperature dependent compaction-creep-recovery and void analysis of compression molded Prepregs. Compos. Part. B-Eeg. 235, 109757 (2022).

Chang, Y. Y. et al. Effect of gums on the rheological characteristics and microstructure of acid-induced SPI-gum mixed gels. Carbohyd Polym. 108, 183–191 (2014).

Brito-Oliveira, T. C. et al. Modeling creep/recovery behavior of cold-set gels using different approaches. Food Hydrocoll. 123, 107183 (2022).

Kodaira, Y., Takano, Y. & Yonezu, A. Characterization of creep deformation behavior of porous polymer membrane under Small-Punch test. Eng. Fail. An. 135, 106149 (2022).

Jahwari, F. A. & Naguib, H. E. Finite element creep prediction of polymeric voided composites with 3D statistical-based equivalent microstructure reconstruction. Compos. Part. B-Eeg. 99, 416–424 (2016).

Farfán-Cabrera, L. I. et al. Determination of creep compliance, recovery and Poisson’s ratio of elastomers by means of digital image correlation (DIC). Polym. Test. 59, 245–252 (2017).

Farfán-Cabrera, L. I. Pascual-Francisco. An experimental methodological approach for obtaining viscoelastic Poisson’s ratio of elastomers from creep strain DIC-Based measurements. Exp. Mech. 62 (2), 287–297 (2022).

Sotomayor-del-Moral, J. A. et al. Characterization of viscoelastic Poisson’s ratio of engineering elastomers via DIC-Based creep testing. Polymers-Basel 14 (9), 1837 (2022).

Koyanagi, J. et al. Time dependence of mesoscopic strain distribution for triaxial woven carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer under creep loading measured by digital image correlation. Mech. Time-Depend Mat. 20 (2), 219–232 (2016).

Wu, C. M. et al. Long-term open-hole tensile creep properties of self-reinforced PET composites measured by digital image correlation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 278, 125633 (2022).

Spathis, G. & Kontou, E. Creep failure time prediction of polymers and polymer composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 72 (9), 959–964 (2012).

Lai, J. & Bakker, A. Analysis of the non-linear creep of high-density polyethylene. Polymer 36 (1), 93–99 (1995).

Jazouli, S. et al. Application of time–stress equivalence to nonlinear creep of polycarbonate. Polym. Test. 24 (4), 463–467 (2005).

Gupta, A. & Raghavan, J. Creep of plain weave polymer matrix composites under on-axis and off-axis loading. Compos. Part. A-Appl S. 41 (9), 1289–1300 (2010).

Luo, W. et al. Long-term creep assessment of viscoelastic polymer by time-temperature-stress superposition. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 25 (6), 571–578 (2012).

Luo, R. K., Zhou, X. & Tang, J. Numerical prediction and experiment on rubber creep and stress relaxation using time-dependent hyperelastic approach. Polym. Test. 52, 246–253 (2016).

Meera, A. P. et al. Tensile stress relaxation studies of TiO2 and Nanosilica filled natural rubber composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48 (7), 3410–3416 (2009).

Fernandes, V. A. & De Focatiis, D. S. A. The role of deformation history on stress relaxation and stress memory of filled rubber. Polym. Test. 40, 124–132 (2014).

Obaid, N., Kortschot, M. T. & Sain, M. Predicting the stress relaxation behavior of glass-fiber reinforced polypropylene composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 161, 85–91 (2018).

Bhagawan, S. S., Tripathy, D. K. & De, S. K. Stress relaxation in short jute fiber-reinforced nitrile rubber composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 33 (5), 1623–1639 (1987).

Yang, F., Das, D. & Chasiotis, I. Microscale creep and stress relaxation experiments with individual collagen fibrils. Opt. Laser Eng. 150, 106869 (2022).

Nekouzadeh, A. et al. A simplified approach to quasi-linear viscoelastic modeling. J. Biomech. 40 (14), 3070–3078 (2007).

Nekouzadeh, A. Genin. Adaptive quasi-linear viscoelastic modeling. In Computational Modeling in Tissue Engineering 47–83 (Springer, 2012).

Oman, S. & Nagode, M. Observation of the relation between uniaxial creep and stress relaxation of filled rubber. Mater. Des. 60, 451–457 (2014).

Abadi, M. T. Micromechanical analysis of stress relaxation response of fiber-reinforced polymers. Compos. Sci. Techno. 69, 7–8 (2009).

Jeya, R., Zhao, Z. & Bouzid, H. A. Creep-Relaxation modeling of HDPE and Polyvinyl chloride bolted flange joints. J. Press. Vess-T Asme. 142 (5), 051303 (2020).

Yue, L. et al. A dual-scale three-dimensional thermo-viscoelastic model for the hot Stamping simulation of thermoplastic composites. Polym. Compos. 44 (3), 1725–1740 (2023).

Meddahid, S. & Ruiz-Baier, R. A mixed discontinuous Galerkin method for a linear viscoelasticity problem with strongly imposed symmetry[J]. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 45 (1), B27–B56 (2023).

Yun, J., Marya, M. & Zolfaghari, A. Methodologies to predict the operational limits of nonmetallic materials in well applications: the cases of hydrocarbon production and carbon dioxide sequestration[J]. AMPP Annual Conference Expo, 000(All-MECC23) p. 15. (2023).

Lefevre, V., Sozio, F. & Lopez-Pamies, O. Abaqus implementation of a large family of finite viscoelasticity models[J]. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2024 (5), 232 (2024).

Brandt, D. C. & Muñoz-Rojas, P. A. Transient analysis of trusses considering nonlinear elastic and viscoelastic material models. Latin Am. J. Solids Struct. 21 (1), e521 (2024).

Harald, G., Nürnberg, R. & Dennis, T. Parametric finite element approximation of two-phase Navier–Stokes flow with viscoelasticity[J]. IMA Journal of Numerical Analysis, pp. drae103. (2025) (2025).

Chen, S. et al. Improving the thermal, mechanical, and insulating characteristics of thermal interface materials with liquid metal-based diphase structure[J]. J. Mater. Sci. 59 (40), 19125–19137 (2024).

Niu, L. et al. Quasi-static compression properties of graphene aerogel. Diam. Relat. Mater. 111, 108225 (2021).

Bakbak, O., Birkan, B. E., Acar, A. & Colak, O. Mechanical characterization of araldite Ly 564 epoxy: Creep, relaxation, quasi-static compression and high strain rate behaviors. Polym. Bull. 79 (4), 2219–2235 (2022).

Park, S. W. & Schapery, R. A. Methods of interconversion between linear viscoelastic material functions. Part i—a numerical method based on prony series. Int. J. Solids Struct. 36 (11), 1653–1675 (1999).

Kashtalyan, M. Finite element analysis of composite materials using abaqus™. Aeronaut. J. 118 (1199), 98–99 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was Funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department [No. BJK2024043], the North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering Doctoral Research Initiation Fund [No. BKY-2024-01], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 52205510], the Central guidance for local scientific and technological development funding projects [No. 246Z1823G].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author statement is provided to outline the individual contributions of authors to the manuscript. Yuezhen Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Xiaoguang Li: Software, Investigation, Visualization. Zhifeng Liu: Resources, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Zhichao Jiang: Validation, Formal analysis. Zhijie Li: Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Ying Li: Project administration, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Li, X., Liu, Z. et al. A novel modeling and analysis of mechanical properties of single-component thermal conductive silica gel. Sci Rep 15, 15163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99953-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99953-2