Abstract

Minor ST segment and T wave (ST-T) abnormalities are commonly seen on the resting electrocardiograms (ECGs) of healthy individuals, but the long-term effects of these findings, particularly in the general population, have not been thoroughly assessed. As a result, our objective was to examine the link between isolated minor ST-T abnormalities in the general population and mortality from both cardiac and non-cardiac causes. The ECGs of 9035 participants within the Mashhad stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorders (MASHAD) study were evaluated. This was followed by a monitoring period of over a decade to investigate mortality results. The electrocardiograms were analyzed for ST-segment and T-wave irregularities using the Minnesota Codes classification system. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was utilized to compare mortality rates for cardiovascular disorder (CVD), coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and all-cause death between cohorts with ECG alterations and those without. Individuals exhibiting isolated minor ST-T changes were predominantly female (p < 0.001), had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (p = 0.031), and were more likely to be unemployed (p = 0.001). No significant differences were observed in age, marital status, educational attainment, smoking status, body mass index, dyslipidemia, and hypertension between the groups. Isolated minor ST-T abnormalities were identified as significant predictors of stroke mortality (p = 0.017). The presence of these ECG changes did not correspond to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality. Upon adjustment for gender, employment status, and diabetes mellitus, the association between minor ST-T changes and all-cause mortality was p = 0.050. Individuals with isolated minor ST-T abnormalities were more likely to die from stroke. Therefore, it is advisable to implement preventive measures for the affected population, particularly women and individuals with diabetes, who are at higher risk of experiencing these ECG changes. Additionally, it is important to closely monitor the clinical status of those affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The resting electrocardiogram (ECG) is a valuable diagnostic tool in cardiac medicine, commonly used in routine examinations to detect heart problems. In addition to clinical applications, ECGs from healthy individuals have been utilized to investigate the prevalence, associations, and predictive capabilities of asymptomatic heart conditions in the general population1. In asymptomatic individuals, nonspecific abnormalities in ECG tracings are commonly observed. The most prevalent findings are ST segment or T-wave abnormalities, or a combination of both (ST-T abnormalities). These ECG changes can be indicative of underlying conditions, which may pose a diagnostic challenge for physicians in terms of definitive confirmation or exclusion2. Advanced age, female gender, elevated systolic blood pressure, current smoking, and the presence of hyperlipidemia were found to be associated with minor ST-T changes3,4.

Numerous studies have shown that ST-T changes, even without other ECG abnormalities, could increase the risk of mortality, particularly related to cardiac issues2,5,6,7,8. However, some studies concluded that only major ECG abnormalities increased cardiac mortality9. Furthermore, it has also been discovered that individuals who exhibit ST-T changes on their electrocardiogram have an increased likelihood of stroke4,10.

The importance of minor ST-T changes in terms of prognosis is not as firmly established. Moreover, earlier research primarily concentrated on ECG abnormalities in high-risk groups like men or older individuals11,12. Due to the association between minor ST-T changes and established cardiovascular risk factors, the calculated risk attributed to minor ST-T changes is contingent upon the management of these traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Currently, clinical practice guidelines do not advise the use of resting ECG for cardiovascular risk assessment in the general population. This is due to the lack of randomized control trials (RCTs) examining the advantages of using resting ECG for health screening, and the marginal enhancement in predictive accuracy observed in models incorporating resting ECG13.

This study utilized long-term data from the Mashhad Cohort study to investigate whether isolated minor ST-T abnormalities are independently associated with mortality risk from cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and all causes in northeastern Iran. Additionally, the study evaluated the risk factors associated with ST-T changes.

Materials and methods

Study sample

The Mashhad prospective cohort study on stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorders (MASHAD) began in 200714. A total of 9035 participants aged 35 to 65 whose ECGs were available and interpretable entered the study. Of the original 9,035 participants, 8,834 were retained after implementing the following exclusion criteria: age outside the range of 35 to 65 years, documented cardiovascular conditions (including a history of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, ECG major abnormalities or other clinically significant heart diseases), lactation or breastfeeding, loss to follow-up, or refusal to continue the study. The participants’ baseline characteristics including age, gender, marital status, job, educational level, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and medical background were all recorded. All participants underwent fasting blood tests to assess their lipid profile and fasting blood glucose levels using standard methods which was previously described14. A cardiologist confirmed the presence of CVD by using a CVD risk questionnaire, a resting 12-lead ECG, and additional tests as required. In this study, diabetes mellitus (DM) was identified by the use of oral hypoglycemic medications or insulin or a fasting blood glucose (FBG) level of ≥ 126 mg/dl15. The definition of dyslipidemia was determined based on the following criteria: elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels exceeding 130 mg/dl (3.36 mmol/l), total cholesterol (TC) levels below 200 mg/dl (5.18 mmol/l), triglycerides (TG) levels surpassing 150 mg/dl (1.69 mmol/l), or reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels falling below 40 mg/dl (1.03 mmol/l for males and 1.30 mmol/l for females)16. Hypertension was identified by a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mmHg or higher and/or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mmHg or higher16,17. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (ID: 981703; ethical code: IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1399.783), and all necessary permits were secured prior to the commencement of the research. Confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were maintained throughout the study.

Definition of isolated minor ST-T changes

Standard 12-lead electrocardiograms were recorded following standard electrode placement rules in a resting supine posture at 25 mm/second. An ECG specialist examined the recordings, and then a supervisory physician reviewed them18. A quality control process that involved a random sample of ECGs being independently coded by a second examiner and comparing the results was implemented to verify the validity of MN coding. Following a consistent interpretation process contributed to ensuring accuracy and consistency; discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Any non-specific ST-segment and/or T-wave irregularities on the electrocardiograms were classified based on Minnesota Codes (MN) fully described in the handbook of MN coding system19 including MN codes of 4 − 3 and 4–4 for minor ST-segment depression and 5 − 3 and 5 − 4 for minor T-wave abnormality.

Follow-up

The study population was monitored for 10 years, with regular contact every three years to prevent loss of communication. These individuals were tracked for all-cause, CVD, CHD, and stroke mortality, with detailed explanations provided about the study and ensuring proper use of the information. The subjects filled out the cause of death questionnaire, and the cause of death was verified using the death registry of the Iranian Ministry of Health.

Statistical methods

The final dataset was analyzed using SPSS version 25, with two-tailed tests applied to all analyses. Data were presented as frequencies (percentages) and compared using the chi-squared test. The association between isolated minor ST-T changes and mortality was evaluated utilizing the Cox proportional hazards model. Log-rank analysis was used to show how survival outcomes differed between the two groups, one with prolonged isolated minor ST-T changes and one without. A threshold of P < 0.05 was set for all statistical comparisons.

Result

In this long-term study, a total of 9035 participants were followed up for over a decade. Participants with confirmed CVD were excluded (N = 201). Out of 8832 left subjects, 226 (2.6%) exhibited isolated minor ST-T changes and 8608 (97.4%) showed normal results. Of the participants, 3503 (39.7%) were male, and 5331 (60.3%) were female. Among subjects with ST-T changes, respectively 5 (2.2%), 44 (19.5%), 158 (69.9%) and 40 (17.7%) subjects had the MN code of 4 − 3, 4 − 3, 5 − 3, and 5 − 4.

Baseline characteristics

Based on Table 1, the majority of participants fell within the 45–54 age range. There were notable variations between the comparison groups including differences in gender, occupation, and presence of diabetes mellitus (DM). Females comprised a higher percentage of the individuals with isolated minor ST-T changes (71.7% vs. 60%, p < 0.001), as did without current employment (70.4% vs. 62.5%, p = 0.001), and individuals with DM (18.8% vs. 13.8%, p = 0.031). No significant variations were found in age (p = 0.549), marital status (p = 0.531), educational level (p = 0.079), smoking status (p = 0.789), obesity (p = 0.444), hypertension (p = 0.117), or dyslipidemia (p = 0.999).

Prognosis

The association between isolated ST-T changes and mortality from all-cause, CVD, CHD, and stroke is demonstrated in Table 2. The presence of ST-T changes was associated with a 4.268-fold increased risk of stroke (95% CI 1.295–14.068, p = 0.017). Furthermore, even after adjusting for confounding factors including gender, job, and DM, individuals were found to have a higher likelihood of mortality from stroke (OR: 3.801, 95% CI 1.138–12.691, p = 0.018) and all causes (OR: 1.680, 95% CI 1-2.820, p = 0.050). However, the confidence interval for all-cause mortality includes one, which suggests that the result is not statistically significant and that the observed effect could be due to random variation rather than a true effect.

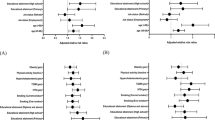

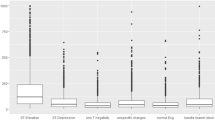

In order to assess differences in the survival probabilities over time between groups with and without isolated minor ST-T changes, we have performed the log-rank test. As shown in Fig. 1, the decline in stroke-related mortality was more pronounced in individuals with isolated minor ST-T changes indicating a strong link between these changes and stroke-related deaths (p = 0.009). However, there was no notable difference in terms of CVD (p = 0.291), CHD (p = 0.521), and all-cause (p = 0.056) mortality between the two groups with and without ST-T changes.

The comparison of survival probability between patients with isolated minor ST-T changes and controls via Kaplan-Meier curves. The survival probability for the group with ST-T changes (red line) drops more sharply, indicating a higher all-cause mortality rate. Censored data points on the curves indicate where death has not occurred by the end of the study period. These data points are included in the analysis but do not contribute to the event rate at that time point—abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disorder, CHD, coronary heart disease.

In a subgroup analysis of ST-T changes, only the MN-5-4 code among the assessed MN codes was found to significantly raise the risks of all-cause mortality and stroke mortality by over 2.8 times and 8.9 times, respectively, after adjusting for confounding factors (p = 0.038 and p = 0.032, respectively). P value according to log rank analysis was respectively 0.041 and 0.029. The survival plots according MN-5-4 code are shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Electrocardiography serves as a noninvasive method utilized for screening cardiac electrophysiological processes. Minor ST-T abnormalities are commonly observed on the resting electrocardiogram of individuals who are in a generally healthy condition, however, the extended significance of these observations has not undergone thorough assessment. The Mashhad Cohort Study yielded valuable information concerning the potential prognostic significance of isolated minor ST-T changes. In our research, we followed 226 individuals with minor ST-T changes for approximately ten years and compared them to a healthy group. None of our patients exhibited significant ECG abnormalities, only isolated minor ST-T changes. In a clinical environment, these minor changes often go unnoticed, yet they have the potential to predict adverse cardiac events. Similar to major ECG changes, they require monitoring and may necessitate specific medications at maintenance doses. Our study focused exclusively on minor ST-T changes, distinguishing it from previous research efforts. Our investigation revealed that minor ST-T abnormalities were strongly linked to risk factors such as male gender (p < 0.001), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.031), and employment status (p = 0.001). These ECG changes were also associated with a higher risk of stroke-related mortality (HR: 3.801, 95% CI 1.138–12.691, p = 0.018) compared to individuals without ECG abnormalities (Fig. 3).

Demographic variability and health correlates of minor ST-T changes

Studies do not unanimously agree on the differences in baseline characteristics regarding the prognostic significance of minor ST-T changes. In 2007, Kumar et al. undertook a systematic review of literature about the clinical implications of minor nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities in asymptomatic individuals2. Their findings suggested that minor ST-T changes were more common in women, black individuals, and the elderly. However, according to Gonçalves et al., minor electrocardiographic abnormalities, such as isolated minor ST-T changes, exhibited a higher prevalence among male individuals, whereas major abnormalities were more frequently observed among females20. Similarly, minor ST-T changes were found to be more common in males, and no association between age and these ECG changes was observed in our study. Kumar et al.‘s study focused on modest ECG alterations in middle-aged and elderly individuals, while our analysis included a wider age spectrum. One reviewed study also revealed that middle-aged individuals exhibited higher minor ST-T changes when examining this minor ECG change at multiple examinations. According to them, drawing a definitive relationship between elder age and minor ST-T changes is also needed to investigate this ECG change in the absence of other ECG abnormalities. The previous documents did not detail specific studies on gender differences in ECG findings across Iran, but some address gender differences in ECG parameters more broadly. ECG parameters vary between genders before and after adolescence, with females experiencing higher resting heart rates and longer QT intervals21. However, a study of 15,084 children and adolescents in Tehran, the capital city of Iran, found that 2,900 had electrocardiographic abnormalities, with boys showing a higher prevalence22. Sex hormones may impact ECG parameters and arrhythmias, with men experiencing increased ST levels after puberty. Additionally, ST segment lability is more pronounced in women than in men23. Notably, research indicates variations in ECG findings, with some more prevalent abnormalities in certain regions. For instance, in a 1972 survey in East Azerbaijan, Northwest Iran, only 45% of ECG tracings were considered normal, with ST depression in 3.9% of men and 14.1% of women, and T wave inversion in 2.2% and 11.6% of men and women, respectively24. In the Tehran Cohort Study, involving 7,630 Iranian adults, sinus bradycardia emerged as the predominant mild electrocardiographic abnormality, detected in 16.11% of participants. Furthermore, modest T-wave inversion and minor ST depression were observed in 3.92% and 3.03% of subjects, respectively. Significantly, 57.88% of those exhibiting mild ECG alterations were male25. Certain studies have shown that individuals with minor ST-T changes have higher blood pressure, use more antihypertensive medications, and have elevated serum lipid levels compared to those in the normal group, both in women and men4,5. Furthermore, as outlined by Bao et al., a higher prevalence of inadequate blood pressure management was noted in hypertensive individuals displaying electrocardiographic nonspecific ST-T abnormalities, particularly among male participants and those with diabetes26. Furthermore, Walsh and his team concluded that minor ST-T changes may play a role in subclinical atherosclerosis. They discovered a statistically significant link between minor ST-T changes and an increase in common carotid intima-media thickness6. In contrast, we did not find a significant association between hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and ST-T changes. Elevated levels of glucose in the bloodstream have been linked to concurrent conditions like high blood pressure, elevated serum lipid levels, and a state that promotes blood clot formation, all of which work together to facilitate alterations in the heart. These subsequent alterations lead to irregularities in the electrocardiogram, which may manifest as non-specific fluctuations in the ST segment and T wave. However, not all studies used Minnesota codes for diagnosing ST-T changes in the general population, nor did they have a uniform criterion for hyperlipidemia. Some considered the use of lipid-lowering medications without assessing the patient’s adherence. Additionally, none of these studies reported significant differences in HDL-C levels, which is a critical dyslipidemia parameter in our study. Furthermore, the studies did not consistently report higher levels of serum cholesterol and blood pressure associated with all the Minnesota codes for minor ST-T changes. Kumar et al. argued also that coronary artery atherosclerosis does not explain the observed minor ECG changes because they excluded patients who had previous ischemic ECG changes or a history of myocardial infarction from their study. Additionally, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring may be more suitable for accurately measuring blood pressure due to the transient nature of minor ST-T changes.

Impact of minor ST-T changes on cardiac mortality

Many previous studies have shown that even minor ST-T changes were linked independent of traditional risk factors to a greater risk of cardiac mortality2,5,8,20,27. Furthermore, there was a strong emphasis placed on the fact that the risk escalates with a greater occurrence (≥ 3 times) of minor ST-T irregularities12. A systematic review conducted in 2007 evaluated studies up to 2005 that investigated the prevalence and prognostic implications of minor ST-T abnormalities. The study revealed that, in the three studies reviewed, the hazard ratios for CHD mortality in multivariable-adjusted ranged from 1.24 to 1.66. Despite acknowledging a scarcity of data regarding race, sex, and age-specific variations in the prognostic significance of minor ST-T abnormalities, the researchers emphasized that these abnormalities in asymptomatic individuals constituted a significant risk factor for CHD and CVD mortality, independent of traditional risk factors2. Nevertheless, our results diverge as we did not observe a statistically significant correlation between ST-T abnormalities and mortality attributed to CVD or CHD. The researchers in this review also recognized the extensive methodological diversity in their literature, underscoring variations among studies in terms of baseline exclusion criteria, definitions of ECG abnormalities, and statistical data analysis. Moreover, the J-HOP (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure) study recommended using the total ST-T area as a quantitative measure to forecast occurrences of CHD and CVD8. They found that individuals in the lowest quartile of ST-T area summation (-2.308 to 0.060 msec. mV) had a higher risk for cardiac outcomes compared to other quartiles (HR: 2.08, 95% CI 1.36–3.16). It is important to note that their study focused on individuals with high-risk factors for cardiac events, so further research is necessary to determine if these findings can be applied to broader populations. Gonçalves et al. conducted a cross-sectional study on Angolan black individuals, finding that both major and minor ECG abnormalities were linked to major cardiovascular risk factors18. However, the ECGs in this study were captured only once at the study’s onset. Since ECG criteria can change over time, the results might vary if multiple ECGs were taken at different time intervals. In a 12-year cohort study by Kim et al., minor ST-T changes were found to be linked to increased cardiovascular events (HR: 2.18, 95% CI 1.45–3.27). The researchers assigned scores to ECG findings and suggested that this ECG score could serve as a valuable predictor of CVD death on its own, potentially enhancing traditional cardiovascular risk assessments in asymptomatic individuals with low risk20. However, unlike our study, they did not differentiate between deaths from CHD and stroke in their assessment of cardiovascular mortality. Additionally, these associations were particularly pronounced during the early stages of follow-up.

All-cause mortality related to minor ST-T changes

According to our study, no association between isolated minor ST-T changes and all-cause mortality was found. Likewise, Greenland et al. found that a minor T-wave abnormality was linked to overall mortality in the age-adjusted model (HR 1.48, p < 0.01), however, such significance was not observed for total mortality after adjustment for blood pressure, serum cholesterol, and lipid levels5. They also concluded that the presence of isolated minor ST-segment depression did not show a significant association with CHD, CVD, or overall mortality in the male population. However, in certain groups, isolated minor ST-T changes could be a standalone risk factor for overall mortality. For example, Zhan et al. found that these ECG alterations in peritoneal dialysis patients raised the risk of all-cause mortality by 1.81 (95% CI 1.11–2.95) and cardiovascular disease mortality by 2.86 (95% CI 1.52–5.37)28.

Link between minor ST-T changes and stroke mortality

According to our study results, even after adjustment for cofounders, isolated minor ST-T changes could increase the risk of stroke mortality by 3.801 (CI: 1.138–12.691, p = 0.018). One potential reason for the connection between minor isolated ST-T abnormalities and stroke could be attributed to neural myocardial stunning, alterations in the autonomic nervous system, and injuries mediated by catecholamine. These factors may contribute to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, the progression of atrial fibrillation, and ultimately the occurrence of a stroke22. The potential role of minor ST-T changes in the development of atherosclerosis could explain another mechanism for this relationship. In a cohort study conducted by Ishikawa et al. in 1992, involving 10,642 individuals from the Japanese population, the research findings indicated a correlation between ST-T changes and the likelihood of experiencing a stroke. Specifically, minor ST-T changes and major ST-T changes increased the hazards of stroke by 2.1 and 8.6 respectively. However, after adjusting for traditional risk factors, the association showed borderline significance (P = 0.055). Further analysis of subgroups revealed that individuals with hyperlipidemia had a significantly higher risk of stroke when presenting with minor ST-T changes compared to those without hyperlipidemia4. Sawano et al. verified this finding and determined that minor isolated ST-T changes raised the risk of ischemic stroke by 27%, with no impact from age, race, or gender10. These findings shed light on the relationship between dyslipidemia and stroke-cause mortality. One possible explanation for this is that the subjects’ hyperlipidemia may have caused both cerebral atherosclerosis and subtle damage to the heart’s target organs due to hypertension, potentially resulting in minor changes in the ST-T segment. Furthermore, based on the results of Ohira et al., middle-aged Japanese men with minor ST-T changes had a 2.3-fold higher risk of death from both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. However, such an association was not observed in women23. The risk of stroke is affected by traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The presence of minor ST-T changes is linked to these risk factors, and the estimated risk associated with these changes depends on whether the traditional risk factors are taken into account. This study revealed that even after adjusting for age, gender, and diabetes mellitus (which varied significantly between the study groups), minor ST-T changes were still linked to a higher risk of stroke-cause mortality.

Impact of isolated T wave abnormalities on mortality risk

According to the Minnesota Code Manual for Electrocardiographic Findings, code 5 − 4 is characterized by a positive T wave amplitude accompanied by a T/R amplitude ratio that does not exceed 1:20 across any of the designated leads: I, II, aVL, or V3 to V6. Furthermore, the R-wave amplitude is required to reach a minimum threshold of 10.0 mm. The presence of codes 4 and 5 within the Minnesota classification system denotes the existence of ischemic abnormalities29,30. According to previous research, Minnesota Code 5 − 4 has been linked to a higher risk of mortality, encompassing both cardiovascular incidents and non-cardiovascular factors. These abnormalities often signify underlying ischemic or arrhythmic conditions, which increase the risk of both sudden and long-term mortality related to the heart29,31. The “study of men born in 1913,” a longitudinal and prospective population-based research involving 839 participants over a span of more than 50 years, revealed that a minor negative T-wave is linked to an increased risk of mortality from all causes as well as cardiovascular-related deaths. This association remained significant even after accounting for other existing ECG abnormalities, with hazard ratios of 1.66 (95% CI 1.13–2.44, P = 0.0098) for all-cause mortality and 1.87 (95% CI 1.13–3.09, P = 0.015) for cardiovascular death. In contrast, there was no significant relationship between negative T-waves and mortality from other causes32. However, the study was limited to men within a specific geographic area, restricting the generalizability of the findings. In a separate investigation led by Holkeri et al., the electrocardiograms of 6,750 individuals from the Finnish general population were analyzed using custom-made ECG analysis software. In this study, Minnesota Codes were not employed and the participants were divided into three distinct categories: (1) those exhibiting negative T-waves with an amplitude of 0.1 mV or greater in at least two of the leads I, II, aVL, V4–V6; (2) individuals with either negative or low amplitude positive T-waves, characterized by an amplitude of less than 0.1 mV and a T-wave to R-wave ratio of less than 10% in at least two of the leads I, II, aVL, V4–V6; and (3) subjects with normal positive T-waves that did not fulfill the previous criteria. The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between T-wave classification and the incidence of sudden cardiac death over a decade-long follow-up period. The findings indicated that while cardiovascular risk factors and diseases are prevalent among those with flat T-waves, these minor T-wave irregularities are also linked to a heightened risk of sudden cardiac death independently33. In contrast to the previous studies, no association was observed between MN code 5 − 4 and mortality from CVD or CHD. However, this ECG abnormality was associated with a 2.8-fold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (P = 0.038). Additionally, our findings indicated a significant relationship between stroke-related mortality and MN code 5 − 4, with an odds ratio of 8.9 (P = 0.032).

Strengths and limitations of the current study

Our study exhibited several notable strengths. Primarily, it encompassed a substantial cohort of participants, enabling the exploration of ECG findings that had hitherto been omitted from predictive models. Secondly, the deliberate inclusion of low-risk individuals devoid of cardiovascular ailments or symptoms was undertaken to formulate a predictive model tailored for risk assessment during health screening procedures. Lastly, we used Minnesota codes that were categorized and documented by a skilled cardiologist during the baseline period. However, further research specifically focusing on isolated minor ST-T changes is needed to make conclusive determinations regarding the significance of these changes in special subgroups such as diabetic patients. Furthermore, one significant drawback of this type of outcome study was the absence of follow-up data on ECG information and alterations in associated risk factors, particularly clinic blood pressure levels. The current study faced additional challenges, including variations in how ECG irregularities were defined, diverse methods used to gather and organize ECG data, the temporary nature of minor ST-T changes, and the range of cardiovascular disease outcomes being examined.

Conclusion

Physician offices and clinics typically possess ECG machines, enabling the utilization of ECG screening as a viable and economical risk evaluation instrument within primary care environments. Understanding the prognostic importance of minor ST-T changes can help clinicians and patients address other modifiable risk factors. Furthermore, these ECG changes may indicate the necessity for annual ECG monitoring, especially in cases of persistent isolated minor ST-T abnormalities due to the higher associated risk.

Data availability

Anonymized data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study.

6. References

Higgins, I., Kannel, W. & Dawber, T. The electrocardiogram in epidemiological studies: Reproducibility, validity, and international comparison. Br. J. Prev. Social Med. 19(2), 53 (1965).

Kumar, A. & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. Clinical significance of minor nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities in asymptomatic subjects: A systematic review. Cardiol. Rev. 15(3), 133–142 (2007).

de la Sierra, A., Gorostidi, M., Aranda, P., Corbella, E. & Pinto, X. Prevalence of atherogenic dyslipidemia in Spanish hypertensive patients and its relationship with blood pressure control and silent organ damage. Revista Española De Cardiología (English Edition). 68(7), 592–598 (2015).

Ishikawa, J., Hirose, H., Schwartz, J. E. & Ishikawa, S. Minor electrocardiographic ST-T change and risk of stroke in the general Japanese population. Circ. J. 82(7), 1797–1804 (2018).

Greenland, P. et al. Impact of minor electrocardiographic ST-segment and/or T-wave abnormalities on cardiovascular mortality during long-term follow-up. Am. J. Cardiol. 91(9), 1068–1074 (2003).

Walsh, I. I. I. J. A. et al. Association of isolated minor non-specific ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities with subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged, biracial population: Coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 20(6), 1035–1041 (2013).

Tikkanen, J. T., Kenttä, T., Porthan, K., Huikuri, H. V. & Junttila, M. J. Electrocardiographic T wave abnormalities and the risk of sudden cardiac death: The Finnish perspective. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 20(6), 526–533 (2015).

Hoshide, S., Kabutoya, T., Yoneyama, T., Fukatani, K. & Kario, K. Electrocardiographic ST-T area assessed by a computerized quantitative method and its relation to cardiovascular events: The J-HOP study. Am. J. Hypertens. 32(3), 282–288 (2019).

Vinyoles, E., Soldevila, N., Torras, J., Olona, N. & de la Figuera, M. Prognostic value of non-specific ST-T changes and left ventricular hypertrophy electrocardiographic criteria in hypertensive patients: 16-year follow-up results from the MINACOR cohort. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 15, 1–7 (2015).

Sawano, M. et al. Electrocardiographic ST-T abnormities are associated with stroke risk in the REGARDS study. Stroke 51(4), 1100–1106 (2020).

Auer, R. et al. Association of major and minor ECG abnormalities with coronary heart disease events. Jama 307(14), 1497–1505 (2012).

Daviglus, M. L. et al. Association of nonspecific minor ST-T abnormalities with cardiovascular mortality: The Chicago Western electric study. Jama 281(6), 530–536 (1999).

Jonas, D. E. et al. Screening for cardiovascular disease risk with resting or exercise electrocardiography: Evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. Jama 319(22), 2315–2328 (2018).

Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. et al. Mashhad stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorder (MASHAD) study: Design, baseline characteristics and 10-year cardiovascular risk Estimation. Int. J. Public. Health 60, 561–572 (2015).

Mansoori, A. et al. Prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus using hematological factors based on machine learning approaches: A cohort study analysis. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 663 (2023).

Sahranavard, T. et al. Factors associated with prolonged QTc interval in Iranian population: MASHAD cohort study. J. Electrocardiol. 84, 112–122 (2024).

Ohishi, M. Hypertension with diabetes mellitus: Physiology and pathology. Hypertens. Res. 41(6), 389–393 (2018).

Saffar Soflaei, S. et al. A large population-based study on the prevalence of electrocardiographic abnormalities: A result of Mashhad stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorder cohort study. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 28(6), e13086 (2023).

Prineas, R. J., Crow, R. S. & Zhang, Z-M. The Minnesota Code Manual of Electrocardiographic Findings (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009).

Gonçalves, M. A., Pedro, J. M., Silva, C., Magalhães, P. & Brito, M. Prevalence of major and minor electrocardiographic abnormalities and their relationship with cardiovascular risk factors in Angolans. IJC Heart Vasculature 39, 100965 (2022).

Moss, A. J. Gender differences in ECG parameters and their clinical implications. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology: The official journal of the international society for Holter and noninvasive electrocardiology. Inc 15(1), 1 (2010).

Khorgami, M. R. et al. Prevalence of electrocardiographic abnormalities among Iranian children and adolescents and associations with blood pressure and obesity: Findings from the SHED LIGHT study. Cardiol. Young 34(6), 1295–1303 (2024).

Nakagawa, M. Gender differences on physiological function test. Nihon Rinsho Japanese J. Clin. Med. 73(4), 601–605 (2015).

Daneshapjooh, M., Nadim, A. & Amini, H. ECG ABNORMALITIES IN RURAL AREAS. Iran. J. Public. Health 4(2). (1970).

Ahmadi, P. et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with major and minor electrocardiographic abnormalities: A report from the Cross‐Sectional phase of Tehran cohort study. Health Sci. Rep. 8(1), e70350 (025).

Bao, H. et al. Nonspecific ST-T changes associated with unsatisfactory blood pressure control among adults with hypertension in China: Evidence from the CSPPT study. Medicine 96(13), e6423 (2017).

Kim, W-D. et al. Electrocardiography score based on the Minnesota code classification system predicts cardiovascular mortality in an asymptomatic low-risk population. Ann. Med. 55(2), 2288306 (2023).

Zhan, X., Zeng, C., He, J., Wang, M. & Xiao, J. Non-specific electrocardiographic ST-T abnormalities predict mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 930517 (2022).

MACFARLANE PW. Minnesota Coding and the Prevalence of ECG Abnormalitiesp. 582–584 (BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Cardiovascular Society, 2000).

Nijpels, G., Van Der Heijden, A. A., Elders, P., Beulens, J. W. & De Vet, H. C. The interobserver agreement of ECG abnormalities using Minnesota codes in people with type 2 diabetes. Plos One 16(8), e0255466 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Prognostic significance of serial Q/ST-T changes by the Minnesota code and Novacode in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 19(6), 1430–1436 (2012).

Sjöland, H., Fu, M., Caidahl, K. & Hansson, P. O. A negative T-wave in electrocardiogram at 50 years predicted lifetime mortality in a random population‐based cohort. Clin. Cardiol. 43(11), 1279–1285 (2020).

Holkeri, A. et al. Prognostic significance of flat T-waves in the lateral leads in general population. J. Electrocardiol. 69, 105–110 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the collaboration and support of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

The study was financially supported by MUMS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The final version of the manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all the authors. Authors agreed to be responsible for all aspects of the work. Details of contributions: Study concept and design: MG, HE, and SSS; data collection: SSS, AHB, MK, PM, RE and RSK; Analysis and interpretation of data: SSS, HE and FF; Drafting of the manuscript and critical revision: FF, SSS, GAF and MG.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and informed consent of participant

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS) (IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1399.783). The study was confirmed to meet the ethical principles of the Helsinki agreement in medical research. Patients provided written informed consent for the publication of this report in compliance with the journal’s patient consent policy.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soflaei, S.S., Farsi, F., Heidari-Bakavoli, A. et al. Association between isolated minor ST-segment and T wave changes with 10 years all-cause and stroke mortality. Sci Rep 15, 35249 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99960-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99960-3