Abstract

Oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150) is a chaperone found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) induced by ER stress, oxidative stress, glutamate toxicity, ischemia, and hypoxia. Increased expression of ORP150 protects the cells by stopping ER stress, maintaining calcium balance, and delaying apoptosis. In this study, we aim to investigate serum ORP150 amount in patients with different severity levels of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Forty-nine patients (25 of severe and 24 of mild-moderate), and 23 healthy controls were included in the study. Routine biochemical measurements and serum ORP150 measurements of all groups and sleep quality measurements of OSA groups were obtained. ELISA was used to measure ORP150 levels in serum samples. In addition, ROC analysis was performed to determine the diagnostic power of the ORP150 parameter. There are significant differences between all three groups in terms of ORP150 values (severe OSA: 8.03 ± 0.4 ng/mL; mild-moderate OSA: 5.54 ± 0.47 ng/mL; control: 4.41 ± 0.25 ng/mL, p < 0.017). The highest ORP150 level belongs to the severe OSA group and there is a direct correlation between the severity of the disease and ORP150 levels. ORP150 value is a distinguishing parameter for OSA and the cut-off value of ORP150 was observed as 7.14 ng/mL. We concluded that serum ORP150 levels can be a differential diagnostic parameter in OSA patients and that disease severity can be determined by serum ORP150 measurement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a clinical condition characterized by the narrowing of the upper airway during sleep due to the decreased tension of upper airway dilator muscles, which varies depending on the sleep phase1. This condition leads to intermittent collapse and narrowing of the upper airway, causing a reduction in airflow and resulting in loud snoring. These events occur in repetitive cycles throughout the sleep period, disrupting the continuity of sleep. As a consequence of pathophysiological hypoxia-ischemia, commonly referred to as “asphyxia,” OSA leads to hypoxemia and acidosis at the tissue level2. Despite its high prevalence, the rate of accurate diagnosis of OSA is remarkably low, with only about 10% of affected individuals receiving a correct diagnosis. This low diagnostic rate leads to a large number of untreated OSA patients, which has direct implications for public health systems due to the associated financial burden and increased healthcare utilization3.

In patients with OSA, partial reduction (hypopnea) or complete cessation (apnea) of the airway can be observed. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), which represents the total number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, is the most widely used parameter for determining the severity of OSA. According to established diagnostic criteria, the severity of OSA is classified as follows: AHI < 5/h indicates no OSA; AHI 5–15/h is classified as mild OSA; AHI 15–30/h as moderate OSA; and AHI > 30/h as severe OSA4,5. Notably, OSA is strongly linked to hypertension, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, and arrhythmias6,7,8,9,10,11. Additionally, the prevalence of other comorbidities such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and goiter is also high in OSA patients. The coexistence of these comorbid conditions exacerbates the overall disease burden and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes12,13.

Oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150), also known as hypoxia up-regulated protein 1 (HYOU1), is a molecular chaperone located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It is induced by various cellular stress conditions, including ER stress, oxidative stress, glutamate toxicity, ischemia, and hypoxia. ORP150 plays a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by assisting in the proper folding of newly synthesized proteins and preventing protein aggregation within the ER14. Increased expression of ORP150 is known to protect cells by alleviating ER stress, maintaining calcium homeostasis, and delaying apoptosis15. Additionally, ORP150 has been observed to increase in cells in response to hypoxic conditions, suggesting its potential role as an adaptive mechanism that enhances cell survival and function under hypoxic stress16. This is also known that ORP150 prevents apoptosis in various tissues17 and helps transport and mature protein in cells in hypoxic conditions18.

Although ORP150 is primarily an intracellular protein, it can be released into the extracellular space and subsequently detected in serum or plasma due to cellular stress, injury, or damage19,20. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between ORP150 overexpression and the pathogenesis of various diseases21,22. However, the levels and biological functions of ORP150 in patients with OSA remain largely unexplored. Given the central role of hypoxia in the pathophysiology of OSA and the hypoxia-responsive nature of ORP150, it is reasonable to hypothesize that ORP150 may be involved in the molecular mechanisms underlying OSA and its related complications.

This study aims to determine serum ORP150 levels in patients with OSA, to investigate the relationship between serum ORP150 levels and disease severity, and to evaluate the diagnostic efficiency of ORP150 as a potential biomarker for OSA. By elucidating the role of ORP150 in OSA, this study seeks to provide new insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease and explore the potential of ORP150 as a diagnostic and prognostic tool in clinical practice.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Demographic data of the control and OSA groups are given in Table 1. There isn’t statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of gender, age and body-mass index (BMI) variables (p > 0.05).

Polysomnographic data

Sleep quality parameters measured by polysomnography are given in Table 2. Except for the periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) values, all sleep quality parameters differed significantly between the groups (p < 0.05). Polysomnographic results showed that there were statistically significant differences in sleep quality, arousal index, apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and saturation-related parameters between mild-moderate and severe OSA groups.

Laboratory parameters and ORP150 levels

Values of biochemical parameters are given in Table 3. Statistically significant difference was found between the groups according to aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), neutrophil, lymphocyte, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean platelet volume (MPV) and C-reactive protein (CRP) variables (p < 0.05). Pairwise comparisons were made to calculate the difference between which groups. p value to be used; since the number of OSA groups was 3 and the number of comparisons was 2, (3¦2) = 3, αBD = 0.05/3 = 0.017. After the Kruskal-Wallis test, the p values obtained by the Mann-Whitney test were compared with the 0.017 value found and the result was decided. The highest levels in AST, ALT, MCV and CRP parameters belong to the severe OSA group. Compared to the control group, the severe OSA and mild-moderate OSA groups had significantly higher levels (p < 0.017). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the severe OSA and mild-moderate OSA groups (p > 0.05). There is a statistically significant difference between mild-moderate OSA and control groups in terms of neutrophil levels (p < 0.017). However, no statistically significant difference was found between mild-moderate OSA and severe OSA and severe OSA and control groups (p > 0.05). For lymphocyte and MPV; There was a statistically significant difference between the severe OSA and control groups (p < 0.017). However, no statistically significant difference was found between mild-moderate OSA and severe OSA; mild-moderate OSA and control (p > 0.05).

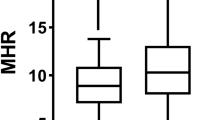

There are significant differences between all three groups in terms of ORP150 values (p < 0.017). The highest ORP150 level (8.03 ± 0.4 ng/mL) belongs to the severe OSA group and there is a direct correlation between the severity of the disease and ORP150 levels (Fig. 1; Table 4). ORP150 values of mild-moderate OSA group and control group were found to be 5.54 ± 0.47 ng/mL and 4.41 ± 0.25 ng/mL, respectively. According to the results of the ROC analysis, ORP150 value is a distinguishing parameter for OSA and the cut-off value of ORP150 was observed as 7.14 ng/mL ROC analysis data and cut-off values are given in Table 5; Fig. 2.

Discussion

In this research, we evaluated the association between serum ORP150 levels and OSA. Our findings demonstrate that serum ORP150 levels are significantly higher in OSA patients compared to healthy controls. Additionally, serum ORP150 levels were positively correlated with the severity of OSA.

OSA is currently recognized as a significant public health concern, affecting 5–15% of the general population. Its prevalence increases linearly with age, at least until 60–65 years, and continues to rise daily23. The most accurate method for diagnosing OSA is overnight polysomnography, which records sleep and respiration, including brain activity, eye movements, heart and muscle activity, and airflow24. However, this method is expensive, time-consuming, and requires additional workforce and physical space in healthcare facilities. Although clinical scoring questionnaires offer practicality, they cannot reliably determine disease severity25. Multiple scoring templates are available for diagnosing OSA, but their accuracy and specificity are insufficient, especially in pediatric populations26. Therefore, there is a need for reliable and practical measurement methods to diagnose OSA and determine disease severity.

The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is known to be associated with OSA severity27. In our study, AHI differed significantly between severe and mild-moderate patient groups, confirming this relationship. However, AHI is not always considered the gold standard and may not accurately reflect the clinical situation28. Consequently, researchers have investigated various biochemical parameters related to OSA severity. Ekin et al. explored levels of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), malondialdehyde (MDA), ischemia-modified albumin (IMA), and NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX-4), finding that all were linked to OSA severity, with 8-OHdG and MDA demonstrating 100% specificity29. Similarly, Yi et al. found an association between C-reactive protein (CRP) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels with OSA severity in a meta-analysis30. However, Wali et al. reported that while CRP, fibrinogen, TNF-α, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were elevated in OSA patients compared to controls, none correlated with disease severity31. Lynch et al. found no association between insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) levels and OSA severity32.

This study is the first to demonstrate that ORP150 levels increase in response to hypoxia severity, with higher ORP150 levels observed in severe OSA patients. ORP150 is one of the few oxygen-regulated proteins synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum in response to hypoxia, with a molecular weight of 150 kDa33. ORP150 plays a protective role against ischemia-reperfusion injury in renal, neural, and cardiac tissues and has cytoprotective effects in nerve cells. It also exhibits anti-apoptotic and neurotrophic properties18,34,35,36,37,38,39. Notably, neurons overexpressing ORP150 show resistance to hypoxic stress40.

In our study, no statistically significant differences were observed between the severe and mild-moderate OSA groups in any biochemical measurements, except for ORP150. ROC analysis revealed that the optimal cut-off value for ORP150 is 7.14 ng/mL, with a specificity of 0.801 and sensitivity of 0.958. To date, no other studies in the literature have examined ORP150 levels in relation to different OSA severity levels. Based on our findings, we propose that serum ORP150 levels can serve as a differential diagnostic marker for OSA and that ORP150 measurements can help determine disease severity.

Limitations and future directions

The main limitation of this study is the relatively small number of OSA patients, highlighting the need for similar studies with larger cohorts. Furthermore, investigating ORP150 levels before and after continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment could provide valuable insights into treatment monitoring. We also believe that future studies on larger populations and experimental animal models will clarify the relationship between OSA and ORP150 levels more accurately.

Methods

Establishment of patient and control groups

This study is designed as an observational study and the ethical permissions were obtained by Malatya Turgut Ozal University Clinical Research Ethics Committee with the decision number 2022/13. G*power 3.1.9.7 program was used to determine the sample size of the study. The sample size was found to be at least 66 (22 in each group) at an effect size of 0.50, a confidence level of 0.95, and a significance level of 0.05. The patient group of the study consists of 49 individuals who applied to Malatya Turgut Özal University Training and Research Hospital Sleep Disorders Centre between 01.08.2022 and 01.11.2022. The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1989) of the World Medical Association. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient (07.28.2022, 2022/13). The clinical examinations of the volunteers participating in the study were performed by pulmonologists with experience in sleep disorders. In addition to the characteristics such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI) and polysomnography parameters were recorded. The 49 volunteers participating in the study were divided into two groups as mild-moderate (n = 24) and severe OSA (n = 25). Severe OSA and mild-moderate OSA groups were determined according to AHI values. The patients were categorized into mild-moderate OSA (AHI, 6–29), and severe OSA (AHI, > 30) groups.

The exclusion criteria for the OSA group were determined as follows:

-

Age < 18,

-

History of malignancy,

-

Presence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease,

-

Those with a history of acute infection or trauma in the last three weeks,

-

Those who use cigarettes, alcohol and drugs,

-

Systemic drug use (steroids, OCS, immunosuppressive drugs, tranquilizers, muscle relaxants).

All procedures for the patients included in the patient group were applied in the same way for the individuals included in the control group (history, exclusion criteria and laboratory tests). In the study, 23 healthy individuals over 18 years of age, whose laboratory tests were in the normal range and did not show OSA symptoms, were included in the control group. Since the control group consisted only healthy people, sleep parameters of the control group did not measure by polysomnography. However, the sleep quality of the control group was evaluated with the Pittsburgh sleep quality scale and individuals with a score between 0 and 5 were included in the study. Flowchart of participant recruitment for the study was shown in Fig. 3.

Polysomnography

Polysomnography findings of the volunteers was appraised by 55-channel polysomnograph (Alice 6 ® Sleepware, Philips Respironics, PA, USA) system. Polysomnography recording data were analysed in accordance with guidelines published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria version 2.441. Apnea was described as a drop in peak thermal sensor excursion by ≥ 90% of baseline for ≥ 10 s. Hypopnea was described as drop in the nasal pressure signal by ≥ 30% of baseline for ≥ 10 s, causing a ≥ 3% decrease in the oxygen saturation (SaO2) pre-event baseline or an arousal. Desaturation was described as a 3% reduction in the SaO2 compared to baseline. The minimum SaO2 was described as the lowest SaO2 value recorded during the night. Mean SaO2 was defined as the average SaO2 value recorded during the night. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was defined as the mean number of apneic and hypopneic episodes per hour of sleep. An AHI > 5/h was considered diagnostic of OSA. Based on their AHI scores, the patients were categorized into mild-moderate OSA (5 ≤ AHI < 30) and severe OSA (AHI ≥ 30) groups according to the AASM. Volunteers with AHI < 5 were categorized as the control group42,43.

Obtaining serum samples and biochemical analysis

Blood samples were taken from the subjects (OSA patients and healthy controls) in 2 gel separator (serum) tubes in the morning after an overnight fast (in case of fasting between 8.00 pm and 8.00 am after dinner). After the collection, the serum tubes were centrifuged at 1200 g for 10 min. Routine biochemistry parameters were studied in the central laboratory on the same day. Analyses of the biochemical markers (aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], and C-reactive protein [CRP]) were performed with Abbott Architect c16000 (Illinois, United States of America) and hemogram analysis (hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocyte, neutrophil, lymphocyte, thrombocyte, mean corpuscular volume [MCV], mean platelet volume [MPV]) were performed with Sysmex Corporation XN-10 (Kobe, Japan) devices. For ORP150 analysis, serum samples were transferred to micro-volume Eppendorf tubes and stored at -80 °C until biochemical analysis. Commercial Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (Cloud-Clone Corp, Cat. No: SEC537Hu, Texas, United States of America) was used to determine ORP150 levels. ELISA measurement was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (Statistical Program in Social Sciences) 25 program was used to analysis of the data. Normal distribution of the data was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significance level (p) for comparison tests was taken as 0.05. Non-parametric test methods were used because of the variables did not have a normal distribution (p > 0.05). Comparisons in independent pairs the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The Kruskal-Wallis test analysis was performed for comparisons in multiple independent groups. Since the p value will increase depending on the increase in the number of comparisons in the variables with difference, the Bonferroni corrected p value was used and it was calculated with “(0.05/binary comparison)”. After the Kruskal-Wallis test, the p values obtained by the Mann-Whitney test were compared with the calculated p values and the result was decided. ROC analysis was performed to determine the cut-off point.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Carberry, J. C., Jordan, A. S., White, D. P., Wellman, A. & Eckert, D. J. Upper airway collapsibility (Pcrit) and pharyngeal dilator muscle activity are sleep stage dependent. Sleep 39, 511–521. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5516 (2016).

Berry, R. B. et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. Deliberations of the sleep apnea definitions task force of the American academy of sleep medicine. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 8, 597–619. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.2172 (2012).

Sánchez-de-la-Torre, M., Campos-Rodriguez, F. & Barbé, F. Obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Respir Med. 1, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70051-6 (2013).

McNicholas, W. T. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 5, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200708-118MG (2008).

Abrishami, A., Khajehdehi, A. & Chung, F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can. J. Anaesth. 57, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-010-9280-x (2010).

Pedrosa, R. P. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension 58, 811–817. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179788 (2011).

Manin, G. et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea in people with type 1 diabetes: prevalence and association with micro-and macrovascular complications. Diabet. Med. 32, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12582 (2015).

Aurora, R. N. & Punjabi, N. M. Obstructive sleep apnoea and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional association. Lancet Respir Med. 1, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70039-0 (2013).

Salles, C., Terse-Ramos, R., Souza-Machado, A. & Cruz, Á. Obstructive sleep apnea and asthma. J. Bras. Pneumol. 39, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132013000500011 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. Correlation between coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and analysis of risk factors. Exp. Ther. Med. 15, 4771–4776. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6070 (2018).

Haddad, L. et al. Impact of thyroidectomy on the control of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in patients with large goiters. Sleep. Breath. 18, 825–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-0950-8 (2014).

Lavie, L. & Lavie, P. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in OSAHS: the oxidative stress link. Eur. Respir J. 33, 1467–1484. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00086608 (2009).

Lavie, L. Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea and intermittent hypoxia–revisited–the bad ugly and good: implications to the heart and brain. Sleep. Med. Rev. 20, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.003 (2015).

Rao, S. et al. Biological function of HYOU1 in tumors and other diseases. OncoTargets Therapy. 14, 1727–1735. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S297332 (2021).

Li, X. et al. HYOU1 promotes cell growth and metastasis via activating PI3K/AKT signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer and predicts poor prognosis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23 (10), 4126–4135. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201901_17914 (2019).

Ozawa, K. et al. 150-kDa oxygen-regulated protein (ORP150) suppresses hypoxia-induced apoptotic cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6397–6404. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.10.6397 (1999).

Montesi, M. et al. Hypoxia mediates osteocyte ORP150 expression and cell death in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 14, 4248–4254. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2016.5790 (2016).

Bando, Y. et al. 150-kDa oxygen-regulated protein (ORP150) functions as a novel molecular chaperone in MDCK cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 278, C1172–C1182. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.6.C1172 (2000).

Wang, D. Q. et al. The 150-kDa oxygen-regulated protein (ORP150) regulates proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy via mediating VEGF. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 110, 104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.04.014 (2019).

Ng, L. L., O’Brien, R. J., Quinn, P. A., Squire, I. B. & Davies, J. E. Oxygen-regulated protein 150 and prognosis following myocardial infarction. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 112, 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20060304 (2007).

Zhang, L. et al. SIRT1 attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in rat models of COPD. Growth Factors. 38, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08977194.2020.1810029 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Involvement of oxygen-regulated protein 150 in AMP-activated protein kinase-mediated alleviation of lipid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11119–11131. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.203323 (2011).

Lévy, P. et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.15 (2015).

Rundo, J. V. & Downey, R. 3rd. Polysomnography. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 160, 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64032-1.00025-4 (2019).

Laharnar, N. et al. Simple and unbiased OSA prescreening: introduction of a new morphologic OSA prediction score. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 13, 2039–2049. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S333471 (2021).

Patel, A. P., Meghji, S. & Phillips, J. S. Accuracy of clinical scoring tools for the diagnosis of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope 130, 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28146 (2020).

Epstein, L. J. et al. Adult obstructive sleep apnea task force of the American academy of sleep medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 5, 263–276 (2009).

Asghari, A. & Mohammadi, F. Is apnea-Hypopnea index a proper measure for obstructive sleep apnea severity? Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 27, 161–162 (2013).

Ekin, S., Yildiz, H. & Alp, H. H. NOX4, MDA, IMA and oxidative DNA damage: can these parameters be used to estimate the presence and severity of OSA? Sleep. Breath. 25, 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02093-2 (2021).

Yi, M. et al. The causal relationships between obstructive sleep apnea and elevated CRP and TNF-α protein levels. Ann. Med. 54, 1578–1589. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2081873 (2022).

Wali, S. O. et al. Putative associations between inflammatory biomarkers, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea. Ann. Thorac. Med. 16, 329–336. https://doi.org/10.4103/atm.atm_644_20 (2021).

Lynch, J. et al. The severity of obstructive sleep apnoea does not influence ambient IGF-I levels. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 94 (3), 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14360 (2021).

Cechowska-Pasko, M., Bankowski, E. & Chene, P. The effect of hypoxia on the expression of 150 kda oxygen-regulated protein (ORP 150) in HeLa cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 17, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1159/000091467 (2006).

Díaz-Bulnes, P., Saiz, M. L., López-Larrea, C. & Rodríguez, R. M. Crosstalk between hypoxia and ER stress response: A key regulator of macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 10, 2951. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02951 (2020).

Chanana, N. & Pati, U. ORP150-CHIP chaperone antagonism control BACE1-mediated amyloid processing. J. Cell. Biochem. 119, 4615–4626. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26630 (2018).

Bourdier, G. et al. High-intensity training reduces intermittent hypoxia-induced ER stress and myocardial infarct size. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 310, H279–289. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00448.2015 (2016).

Wu, Y. B. et al. CHOP/ORP150 ratio in endoplasmic reticulum stress: a new mechanism for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 32, 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354444 (2013).

Sanson, M. et al. Oxygen-regulated protein-150 prevents calcium homeostasis deregulation and apoptosis induced by oxidized LDL in vascular cells. Cell. Death Differ. 15, 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2008.36 (2008).

Kitao, Y. et al. Expression of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone (ORP150) rescues hippocampal neurons from glutamate toxicity. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1439–1450. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI12978 (2001).

Tamatani, M. et al. ORP150 protects against hypoxia/ischemia-induced neuronal death. Nat. Med. 7, 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/85463 (2001).

Berry, R. B. et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 13, 665–666. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6576 (2017).

Geçkil, A. A. et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX as a marker of disease severity in obstructive sleep apnea. Med. (Kaunas). 58, 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58111643 (2022).

Kıran, T. R. et al. The effects of disease severity and comorbidity on oxidative stress biomarkers in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. Breath. 28, 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-023-02870-9 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ö.O., T.R.K. and M.E. designed the study. A.A.G., N.K.B. and E.I. enrolled the patients and organized database. Ö.O. and M.E performed the data analysis. T.R.K. and F.I. performed statistics. Ö.O. and M.E. contributed to data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. T.R.K. and EI contributed to critical review and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otlu, Ö., Erdem, M., Kıran, T.R. et al. Oxygen regulated protein 150 can be considered as a severity indicator in obstructive sleep apnea. Sci Rep 15, 26107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99987-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99987-6