Abstract

Highway flood-damage blocking poses a critical threat to transportation system resilience, yet risk assessment is often limited by insufficient modeling of temporal disaster evolution, highly imbalanced data, and weak model interpretability. To address these challenges, this study proposes an integrated modeling framework that combines temporal data augmentation, machine learning, and interpretable mechanism analysis. Three data-balancing strategies—Time-series Generative Adversarial Network (TimeGAN) augmentation, undersampling, and a hybrid approach—were systematically compared to handle imbalanced temporal data. Six machine learning models (Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, Decision Tree, eXtreme Gradient Boosting, and Multilayer Perceptron) were evaluated, and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was used to quantify factor contributions and explore nonlinear effects and interaction patterns. Results show that the Multilayer Perceptron trained on TimeGAN-augmented sequences achieved the highest performance, with an F1 score of 49.81% and PR-AUC of 49.46%. SHAP analysis identified key drivers and their threshold effects: Daily precipitation exceeding 2.8 mm, 7-day effective precipitation (EP 7) exceeding 22 mm, temperature above 21 °C, and average road-stream distance within 1 km (ARSD) above 0.15 km significantly increase the risk of highway flood-damage blocking. High temperature conditions are more likely to coincide with heavy precipitation and elevated EP 7, and their combined effects further amplify blocking risk. Factor contributions also varied across methods, reflecting SHAP’s ability to capture nonlinear effects and reveal interaction patterns, whereas linear regression mainly reflects independent linear effects. By integrating temporal generation, systematic model evaluation, and interpretable analysis, this study enhances the accuracy and reliability of highway flood-damage blocking prediction, providing quantitative guidance for flood damage prevention and resilience improvement of highway systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highway flood damage refers to damage caused by hydrological factors such as floods and water accumulation1. This results in the destruction, deformation, or functional failure of highway components including the pavement, subgrade, slopes, drainage facilities, and bridges. It typically arises from the coupling effect of internal factors (such as topography, geological structure, stratigraphic lithology) and external factors (such as climate and hydrological environment)2,3.

Highway blocking4 refers to prolonged obstruction or interruption of traffic caused by unexpected events (such as severe weather, geological disasters, or traffic accidents) or planned activities (such as road maintenance or major public events). Among these events, highway blocking triggered by flood damage is termed highway flood-damage blocking (hereinafter referred to as flood-damage blocking). Once such blocking occurs, it may exert severe and far-reaching impacts on economic and social operations, as well as on people’s daily lives5.

According to data from the Highway Monitoring and Emergency Response Center of China’s Ministry of Transport, a total of 60,967 natural highway blockings occurred in China between 2021 and 2022. Among these, flood-damage disasters accounted for over 40% of natural highway blocking. The rapid expansion of the highway network also demands higher standards for preventing flood damage disaster risks. By the end of 2024, China’s total highway mileage reached approximately 5.490 million kilometers6, ranking among the highest globally. Furthermore, the spatial and temporal distribution of global natural disasters is becoming increasingly sudden and anomalous. Extreme weather events are occurring more frequently, with torrential rains, extreme heatwaves, freezing rain and snow, and geological hazards showing an increasing trend7. Consequently, the risk of flood damage disasters is likely to escalate in the future.

Therefore, identifying the key factors influencing flood-damage blocking and establishing a scientific prevention and control framework are crucial for enhancing the disaster resilience of road networks and ensuring the reliable operation of vital transport networks. Scholars have conducted extensive research across multiple dimensions—including engineering structures, environmental coupling—to thoroughly elucidate the formation mechanisms of flood damage to highways.

In the field of engineering structures, research typically employs physical models to examine the impacts of hydrological conditions on road materials. Smyl et al.8 utilized an unsaturated seepage model to reveal the long-term effects of moisture infiltration on concrete durability, while Kringos and Scarpas9 quantitatively analyzed the weakening effect of moisture on asphalt bonding performance through experimental methods. In terms of environmental coupling, researchers commonly adopt physical simulations and statistical approaches to investigate the triggering processes of rainfall-induced hazards. Zeng et al.10 applied finite element analysis to systematically integrate meteorological, topographic, lithological, and construction-related factors along highways, thereby elucidating the disaster-causing mechanisms of short-term continuous heavy rainfall-induced highway damage. Sun et al., using a logistic regression approach, incorporated terrain, geological, and climatic variables to conduct regional landslide susceptibility assessments11. Although physical models and statistical models have been widely used in analyzing flood damage , their ability to capture nonlinear interactions among high-dimensional multivariate factors remains limited, making it difficult to fully represent the complex relationships inherent in hazard processes. This limitation has driven the demand for more powerful analytical tools.

In recent years, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies, the application of machine learning methods in mining features from multi-source heterogeneous data has expanded considerably, offering new perspectives for analyzing inducing factors of flood-damage blocking events12. Li et al.13 employed three machine learning models—Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN)—to comparatively analyze records of flood-damage blocking events in China collected from social media, revealing that road class, longitudinal position, mean annual precipitation, and slope are the most influential triggering factors. Wang et al.14 conducted a systematic comparison of multilayer perceptron (MLP), convolutional neural network (CNN), and long short-term memory network (LSTM) models, achieving long-term dynamic assessments of the failure probability of reservoir bank landslides while accounting for spatial variability in soil properties.

Although previous studies provide a foundation for understanding highway flood-damage blocking, critical limitations remain: most rely on static geographical conditions and ignore the temporal evolution of events, rare blocking occurrences lead to imbalanced datasets that challenge traditional methods15,16, and machine learning models often have weak interpretability, limiting practical value for resilience management.

To address the limitations of existing research, this study proposes an integrated modeling framework for highway flood-damage risk that integrates data balancing, machine learning-based prediction, and interpretability analysis. The specific objectives are as follows:

-

For imbalanced time-series data, we develop and systematically compare three categories of data-balancing strategies, including standalone generative time-series augmentation methods17, standalone undersampling methods, and hybrid strategies that combine the two. These approaches aim to improve class distribution while preserving temporal dependencies.

-

Through comprehensive model comparisons18, we establish a machine learning model system suitable for predicting flood-damage blocking and formulate a systematic performance evaluation procedure.

-

By incorporating Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)19,20, we construct a transparent and interpretable framework for analyzing disaster-causing mechanisms. This framework quantifies the contributions of key influencing factors and uncovers their nonlinear interaction effects, thereby enhancing the credibility and practical value of the model in highway infrastructure resilience management.

By integrating multiple methods, this framework not only improves predictive accuracy, interpretability, and practical utility but also deepens domain understanding, thereby advancing research in highway flood-damage risk assessment and infrastructure resilience management.

The subsequent structure of this study is as follows: Section “Materials” introduces the characteristics of the study area and describes the data sources used and their preprocessing workflow. Section “Methodology” elaborates on the models for predicting flood-damage blocking and the methods for identifying key influencing factors. Section “Results and discussions” evaluates model performance and explores the mechanisms of influencing factors. Section “Conclusions” summarizes the conclusions of this paper and proposes future research directions.

Materials

Study area

Sichuan Province (Fig. 1) in southwestern China (26°03′N–34°19′N, 97°21′E–108°12′E) features a distinct stepped topography, descending from the high-altitude western regions to the low-lying eastern plains21. Its eastern basin (400–750 m) comprises plains and hills, while the west transitions to the Tibetan Plateau’s Hengduan Mountains (3,000–4,500 m). This region is highly prone to flood damage disasters, recording the highest number of highway flood-damage incidents in China from 2021–2022. By the end of 2023, the total mileage of highways in Sichuan Province had reached 418,000 km, ranking first in China22. Given the increasing exposure of highways to extreme hydrometeorological events and the rapid expansion of highway networks, this study selects Sichuan Province as a representative study area.

Study area and slope distribution of the study region.This map was generated from the DEM data described in Table 1 and processed and visualized with ArcGIS (version 10.7.0; https://www.esri.com).

Data sources

The data used in the present study mainly include: 1) Flood-damage blocking, 2) Digital Elevation Model (DEM), 3) Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), 4) Land cover, 5) Hydrology and road vector data, 6) Road vector data, 7) Daily cumulative precipitation, 8) Mean daily temperature, 9) Population. The detailed data information is shown in Table 1.

This study utilized flood-damage blocking as the target variable, focusing on the impact of flood-damage events such as floods, debris flows, and landslides on major road categories including highways, national roads, and provincial roads. The research used data from the high-frequency period between April and October each year, integrating 8,989 daily municipal-level records, with the shortest blocking duration being 0.5 h. The dataset was typically imbalanced, with 7,684 non-blocking events vastly outnumbering 1,304 blocking cases.

To systematically investigate the potential drivers of flood-damage blocking in Sichuan Province (Fig. 2), this study categorizes the explanatory factors listed in Table 1 into four major groups: topography and landform, hydrology, meteorology, and population and infrastructure.

Data processing

The specific processing methods for the original data are as follows:

-

A.

Topography and Landform.

This study developed a GIS workflow to analyze terrain slope, vegetation coverage, and the distribution of key land cover types—swamp, unconsolidated bare areas (UBA) across Sichuan using DEM, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and land cover data.

-

B.

Hydrology.

Metrics for regional hydrology and river systems:

-

Drainage Density (DD)-the ratio of hydrographic line length to hydrographic polygon area, a key indicator of hydrological network development24.

-

Road-stream proximity factors: Using ArcGIS proximity analysis tools, a 1 km search radius was applied to compute the straight-line distance from each road segment to the nearest stream within that radius. If no stream was found within the 1 km threshold, the distance was recorded as a null value; if a road intersected a stream (e.g., at bridges or culverts), the distance was assigned a value of 0. Following these calculations, the results were aggregated by municipal administrative units, and two indicators were derived for each city: the Maximum Road-Stream Distance within 1 km (MRSD) and the Average Road-Stream Distance within 1 km (ARSD).

-

C.

Meteorology.

Meteorological factors were assessed using daily-scale data. Specifically, daily cumulative precipitation (precipitation) and mean daily temperature (temperature) were employed, along with the 7-day effective precipitation (EP 7). The EP 7 was calculated per Eq. (1) 25.

where \({R}_{i}\) denotes the precipitation on the \(i\)-th day prior to the event, and \(K\) is the effective precipitation coefficient (\({\text{K}}\text{=0.84}\)).

-

D.

Population and Infrastructure.

Population and infrastructure factors were characterized by two metrics: (1) Population Density (PD), calculated using municipal-level demographic data from the Sichuan Statistical Yearbook 2022; (2) Road Density (RD), derived from road vector data via ArcGIS spatial analysis tools.

Data sampling

In this study, the original time series data was divided sequentially, with the first 80% of the period allocated to the training set and the remaining 20% reserved for testing. Although the resulting class distribution—approximately 7.5:1 in the training set and 3:1 in the test set—does not represent an extreme imbalance, it is sufficient to bias standard machine learning models toward the majority class. Real-world time series data often exhibit such skewed distributions, which can reduce predictive performance on rare events and increase the risk of overfitting under limited data conditions. To mitigate these issues, improve model generalization, and enhance predictive robustness, we applied three balancing strategies: TimeGAN augmentation, undersampling, and hybrid sampling.

Undersampling balances datasets by reducing majority class samples to match the minority class size. While this significantly accelerates training, it risks losing valuable information. Oversampling conversely increases minority class samples to align with the majority class. This preserves all original majority samples but extends training time and may cause overfitting, as it typically relies on synthetic data generation. Hybrid Sampling combines both techniques to balance datasets, aiming to leverage their advantages while mitigating their drawbacks. However, it tends to introduce higher complexity and computational costs.

This study implemented random undersampling by eliminating a portion of majority-class samples through random deletion26. Given that the dataset consists of time-series data, which possesses inherent temporal dependencies, continuity, and sequential patterns, typical interpolation-based oversampling methods such as SMOTE and ADASYN are unsuitable. Therefore, to generate additional minority-class sequences while preserving temporal dependencies, the Time-series Generative Adversarial Network (TimeGAN) was employed. TimeGAN synthesizes new sequences by (1) training a generator to produce synthetic sequences from random noise, and (2) training a discriminator to distinguish between real minority-class sequences and generated ones, through adversarial training until the generator can produce realistic, temporally coherent samples27. The Hybrid Sampling approach combines TimeGAN-generated minority-class sequences with undersampling of the majority class. This strategy is motivated by two considerations: it ensures adequate representation of rare events while preserving temporal structure, and it reduces potential noise and class overlap from the majority class. By integrating these complementary components, the hybrid approach mitigates class imbalance more effectively than using either component alone.

Sampling techniques were exclusively applied to the training dataset during model training, while the unsampled datatest set was reserved for final performance evaluation. By comparing model performance across differently sampled training datasets, the optimal preprocessing method for maximizing predictive accuracy was determined.

Data validation

To evaluate model generalization on a time-series imbalanced binary classification dataset, mitigate the risk of overfitting, and make full use of the available samples, this study employed a time-series fivefold cross-validation scheme28. This approach strictly preserves the temporal order of the data, dividing it into sequentially expanding training sets and subsequent validation sets in each fold, thereby effectively preventing future information leakage and ensuring temporally valid evaluation. Within each fold, the training set was sampled to alleviate class imbalance, while the validation set retained the original temporal order and class distribution to simulate real-world deployment conditions. Model performance was primarily assessed using the F1 score, with the final performance metric reported as the average across all validation folds.

Methodology

Overview

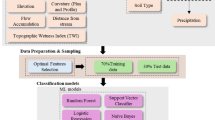

In this study, we developed a unified modelling framework that integrates time-series data augmentation, machine learning prediction. As illustrated in the methodological framework (Fig. 3), the original time-series data were first chronologically divided into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%). Model development was conducted using fivefold time-series cross-validation for hyperparameter optimisation. For each fold, the training data (the first four folds) were standardised and subjected to either no resampling (baseline) or one of three data-balancing strategies: TimeGAN augmentation, undersampling, or a combined TimeGAN-plus-undersampling method. The validation fold was standardised using the training fold parameters but was not resampled. The processed training datasets were then used to train six machine learning models: Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Model performances on the validation folds were used to determine the optimal hyperparameters.

Following hyperparameter optimisation, each model was retrained on the fully standardised training set under each sampling strategy. The unseen testing set was subsequently used to obtain the final performance metrics, based on which the best performing model was identified. Finally, explainability analysis was conducted to reveal the dominant factors and mechanisms influencing flood-damage blocking risk.

Machine learning methods

A comparative analysis of machine learning models was conducted for flood-damage blocking prediction. In all models, the response variable is defined as a binary indicator. Specifically, let \(\text{Y}\in \left\{\text{0,1}\right\}\) denote the observed outcome, where \(\text{Y}=1\) represents the occurrence of a flood-damage traffic blocking event and \(\text{Y}=0\) denotes non-occurrence. The following subsections describe the theoretical foundations and mathematical formulations of each model.

LR, as a classical statistical model, effectively elucidates the multiple regression relationships between the dependent variable and multiple explanatory variables11. For a binary response, the linear predictor of the logistic regression model is given by:

where \(\upeta\) is the linear predictor, \({X}_{i}(i=\text{0,1},\dots n)\) denotes the \(i-\text{th}\) explanatory variable, and \({a}_{i }(i=\text{0,1},\dots n)\) represents the regression coefficient of the explanatory variable. The probability of flood-damage blocking event occurrence is modeled as:

The predicted probability \(\mathcal{P}\) is subsequently converted into a binary class label by applying a predefined threshold, yielding the final classification result.

SVM is a supervised learning model based on statistical learning theory, demonstrating strong generalization capabilities in binary classification tasks29. In this study, the original binary response variable \(\text{Y}\in \left\{\text{0,1}\right\}\) was internally re-encoded for SVM training as \({y}_{i}\in \left\{-1,1\right\}\). The SVM decision function is expressed as:

where \(f(x)\) is the predicted class label, \({\alpha }_{i}\) denotes the Lagrange multiplier, \(K\left(x,{x}_{i}\right)\) is the kernel function that maps features into high-dimensional space, and \(b\) is the bias term.

RF, as an ensemble learning model, significantly enhances generalization capability and robustness by aggregating prediction results from multiple decision trees30. RF constructs inter-tree diversity through Bootstrap sampling with replacement and suppresses overfitting by incorporating feature randomness. The final output is the probability of event occurrence:

where \(P\) is the final predictive probability, and \({p}_{t}\left(x\right)\) denotes the predictive probability output by each individual tree. The final binary class label is obtained by thresholding the predicted probability.

DT, as a non-parametric ML model, constructs a tree-like structure through recursive data partitioning, providing intuitive revelation of nonlinear relationships and interaction effects between dependent and explanatory variables31. For the binary response variable of flood-damage blocking events, the DT model generates discriminant rules through feature selection and threshold splitting, ultimately outputting the probability of event occurrence at leaf nodes:

where \({N}_{1}\) represents the number of samples with flood-damage blocking events in the current leaf node, and \({N}_{0}\) denotes the number of samples without flood-damage blocking. Class labels are determined based on whether \(P\) exceed the threshold.

XGBoost optimizes models through gradient boosting and regularization, iteratively constructing decision trees to reduce errors and prevent overfitting. Its core mechanisms include objective function optimization and gradient-based tree construction. Compared to RF which also belongs to ensemble models, XGBoost typically demonstrates enhanced accuracy, generalization capability, and computational efficiency32. The objective function of XGBoost comprises two components: a loss function and a regularization term.

where \(T\) is the number of tree leaf nodes, \({\omega }_{j}\) denotes the weight of the \(j-th\) leaf node, and \(\gamma\) and \(\lambda\) are regularization coefficients.

During each iteration, XGBoost trains decision trees by optimizing the objective function. For the tree model \({f}_{t}\left(x\right)\) at the \(t-th\) iteration, the optimization objective is to minimize the loss function. This is achieved by approximating the loss function through Taylor expansion and incorporating second-order gradient information, as shown in Eq. (8):

where \({g}_{i}\) and \({h}_{i}\) represent the first-order gradient and second-order gradient of the loss function, respectively. The final probability for each class is computed via the Sigmoid function. The model ultimately converts probabilities into class label by applying a threshold.

MLP, as a core architecture of artificial neural networks, effectively addresses the limitations of traditional linear models in handling complex data relationships through its distinctive nonlinear modeling capability and automatic feature abstraction mechanism. By leveraging the synergistic interaction between multiple hidden layers and nonlinear activation functions, this model not only captures high-order interaction effects between explanatory variables and dependent variables33,but also enables sophisticated pattern recognition. For classification tasks, MLP progressively maps input features into binary decision space through layer-wise nonlinear transformations, formally expressed as:

where \(\text{X}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{\text{n}}\) denotes the input feature vector composed of explanatory variables; \({\text{W}}^{(1)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{\text{m}\times \text{n}}\) and \({\text{W}}^{(2)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{1\times \text{m}}\) represent weight matrices, respectively, \({\text{b}}^{(1)}\) and \({\text{b}}^{(2)}\) represent the corresponding bias terms. \(\text{g}\left(\cdot \right)\) signifies the hidden layer activation function, and \(\upsigma \left(\cdot \right)\) indicates the Sigmoid function at the output layer. The output \(\text{P}\) represents the predicted probability of event occurrence and is subsequently converted into a binary class label by applying the threshold.

Model tuning

Hyperparameter tuning was conducted using Optuna’s Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) algorithm, a Bayesian optimization–based method34 that adaptively models the relationship between hyperparameters and model performance through probabilistic density estimation. Unlike Gaussian-process-based Bayesian optimization, the TPE algorithm separates good and poor parameter regions and exploits their density ratios to propose new hyperparameter candidates, thereby enabling efficient exploration of high-dimensional and heterogeneous search spaces. For each model, the maximum number of optimization iterations was set to 100, ensuring a balance between computational cost and sufficient exploration of the hyperparameter domain.

A fivefold time-series cross-validation scheme was employed to respect temporal dependencies in the data and to avoid information leakage across folds. In each fold, features were standardised using training-fold statistics, and the same scaling was applied to the validation fold. Subsequently, data balancing strategies were applied only to the standardized training data prior to model training, while the validation data remained untouched.

The selection of hyperparameters for tuning was guided by the structural characteristics and performance sensitivities of each model class. For Logistic Regression, C and penalty were optimized because they directly govern the regularization strength and sparsity of the solution, thus influencing the bias–variance trade-off. For SVM, the parameters C and kernel were chosen given their critical roles in determining margin flexibility and enabling the model to capture nonlinear relationships. For Random Forest, n_estimators, max_depth, and max_features were tuned because they jointly control ensemble diversity, tree complexity, and feature randomness—key factors affecting predictive stability and robustness. For Decision Tree models, max_depth, min_samples_split, and min_samples_leaf were optimized because these parameters regulate tree growth, node purity thresholds, and overfitting behavior. XGBoost tuning focused on learning_rate, n_estimators, max_depth, and min_child_weight, which jointly determine boosting dynamics, model complexity, and regularization strength. For MLP, learning_rate, n_layers, and the sizes of individual hidden layers were tuned, as they fundamentally shape network capacity and convergence behavior. The hyperparameter search ranges used in the optimization process and the final selected optimal hyperparameters for each model are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Model evaluation and comparison

Model performance is evaluated using the following metrics:

Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly classified samples to the total number of samples.

Precision represents the proportion of actual positive samples among those predicted as positive by the model.

Recall represents the percentage of all positive samples in the dataset that are correctly predicted as positive.

F1 score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall.

where \(TP\) refers to samples correctly predicted as the positive class, \(FN\) refers to actual positive-class samples incorrectly classified as negative, \(FP\) refers to actual negative-class samples incorrectly classified as positive, \(TN\) refers to samples correctly predicted as the negative class.

PR-AUC is the area under the Precision-Recall curve35. This value comprehensively measures the overall balanced performance achieved by a classification model between precision and recall. When class distribution is imbalanced, PR-AUC effectively reflects the model’s robustness in identifying positive classes.

Given the severe class imbalance in flood-damage blocking data, we selected the F1 score as the primary metric for evaluating model performance. This metric synthesizes both Precision and Recall, providing a more objective reflection of the model’s ability to identify the positive class as the minority class. It effectively avoids the issue where accuracy becomes unreliable due to data skewness. When F1 score between models are comparable, PR-AUC is further compared. This metric comprehensively assesses a model’s performance in identifying positive classes across different decision thresholds, particularly in highly imbalanced data scenarios, thereby ensuring the model achieves a more precise balance between Precision and Recall.

Repeatability assessment

To evaluate the repeatability and reproducibility of the proposed method under identical testing conditions, we employed a Moving Block Bootstrap (MBB) resampling strategy36. Unlike the standard bootstrap, MBB preserves the temporal dependency structure of time-series data by resampling contiguous blocks of samples rather than individual observations. Each bootstrap replicate was generated by randomly selecting enough contiguous blocks from the test set, with each block sampled with replacement, and then concatenating them to form a pseudo-test set of approximately the same length as the original.

In our experiments, the block length was set to 8 to cover the temporal dependency span of the sequences. A total of 1000 bootstrap replicates were generated to obtain a stable empirical distribution of the performance metrics. For each metric, the 5th and 95th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution were reported as the confidence interval, and the interval width was used as a quantitative indicator of reproducibility across different models and sampling strategies.

Results and discussions

Model fit result

The time series dataset was partitioned in chronological order, with the first 80% of the time period used as the training set and the remaining 20% used as the test set. During training, we employed time-series fivefold cross-validation on the training set to evaluate model generalization performance. We applied TimeGAN, undersampling, and hybrid sampling techniques to the training data, training corresponding models on each dataset. The performance metrics of all models were ultimately evaluated on the test set.

Owing to the class imbalance in the flood-damage blocking data, the F1 score was selected as the primary evaluation metric, and AUC-PR, as shown in Fig. 4a-d, was used as the secondary metric to comprehensively assess model performance. Comparing the performance of various models on the three different sampling datasets and the original dataset (Table 2) reveals: LR achieves its best performance on the TimeGAN dataset (F1 = 43.82%, PR-AUC = 38.15%); SVM achieves its best performance on the Original dataset (F1 = 47.79%, PR-AUC = 45.85%); RF achieves its best performance on the undersampling dataset (F1 = 48.85%, PR-AUC = 48.75%); DT achieves its best performance on the Undersampling dataset (F1 = 43.24%, AUC-PR = 36.69%); XGBoost achieves its best performance on the Original dataset (F1 = 49.10%, PR-AUC = 53.14%); MLP achieves its best performance on the TimeGAN dataset (F1 = 49.81%, PR-AUC = 49.46%).

Further comparison of the above best-performing model-dataset configurations reveals that MLP on the TimeGAN dataset outperformed the others.

As shown in Table 2, the cross-validation F1 and test-set F1 remain relatively close, with no model exhibiting a large drop between training-phase validation and final testing. In particular, although neural-network-based MLP models are more susceptible to overfitting when data are limited, the MLP combined with the TimeGAN-augmented dataset demonstrates good generalization: for example, the MLP with TimeGAN configuration achieves a 5-cv F1 score of 0.49 and a test-set F1 score of 0.50, indicating that the synthetic samples generated by TimeGAN enhanced model robustness without causing noticeable overfitting. Similar patterns are observed for other models, where differences between training-validation and test F1 generally remain within 0.05, further confirming that model performance is stable and not overly dependent on the training folds.

Repeatability result

Figure 5 presents the 90% confidence intervals of the F1 score estimated using the MBB. The horizontal axis denotes different combinations of models and data-processing strategies, while the vertical axis shows the MBB-derived mean F1 scores along with their corresponding confidence intervals. A narrower confidence interval indicates greater model stability.

As shown in Fig. 5, the models exhibit different levels of stability. On the original dataset, DT exhibits the highest stability, followed by SVM. On the undersampling dataset, DT and SVM demonstrates the greatest stability, with XGBoost ranking second. For the TimeGAN dataset, DT shows the highest stability, with MLP following. In the hybrid sampling dataset, XGBoost achieves the best stability, followed by MLP and SVM.

Overall, although MLP is not the most stable model across all dataset scenarios, its stability remains at a comparatively strong level. Combined with the findings in Section “Model fit result”, which show that MLP achieves the best classification performance on this dataset, MLP is selected as the final model for the subsequent factor analysis experiments.

Analysis of factors

SHAP, based on game theory and local interpretability theory, is a classical interpretation framework37. It calculates the marginal contribution of each feature by considering all possible subsets of features. While SHAP values reflect feature importance, they also indicate the direction (positive or negative) of each feature’s impact on the outcome. The specific principle is shown in Eq. (14).

where \({\phi }_{i}\left(v\right)\) represents the SHAP values for feature \(i\), \(f\left(S\right)\) denotes the predicted value for feature subset \(S\), \(N\) is the set of all features, and \(\left|\cdot \right|\) indicates the size of set \(\cdot\).

To investigate factors influencing flood-damage blocking, the best performing MLP model trained on the TimeGAN dataset was selected for SHAP analysis. SHAP offers unique advantages: it quantifies directional influence (positive/negative) through SHAP values, revealing whether features promote or inhibit outcomes; it decouples interaction effects among features using game-theoretic principles. These capabilities allow SHAP to comprehensively uncover driving mechanisms behind flood-damage blocking.

Consequently, SHAP analysis was applied to identify key factors. Figure 6 presents the SHAP summary plot, in which the horizontal axis represents the SHAP values and the vertical axis lists the feature variables in descending order of their importance. The color of each point indicates the magnitude of the feature value: darker colors correspond to larger feature values, while lighter colors correspond to smaller ones. As shown in Fig. 6, precipitation, EP 7 and temperature from the meteorology category, along with ARSD from hydrology, demonstrate relatively high global feature importance. In contrast, the global importance of features related to population and infrastructure and topography and landform is comparatively lower.

To further investigate the relationship between individual features and flood-damage blocking, features with high global importance were selected to construct SHAP dependence plots (Fig. 7), enabling the quantification of their monotonic and nonlinear relationships with highway flood-damage blocking risk.

As shown in Fig. 7a, precipitation exhibits a threshold effect on flood-damage blocking. When precipitation < 2.8 mm, 98% of SHAP values are negative, indicating an inhibitory effect on flood-damage blocking within this range. Conversely, when precipitation > 2.8 mm, 96% of SHAP values are positive, demonstrating a promotive effect. Heavy precipitation directly increases surface runoff and soil moisture content, exacerbating slope instability and roadbed erosion38, thereby confirming precipitation as the dominant factor.

EP 7, reflecting the medium-to-short-term precipitation accumulation effect, also exhibits a threshold effect on flood-damage blocking. As shown in Fig. 7b: when EP 7 < 22 mm, 89% of SHAP values are negative, indicating an inhibitory effect on flood-damage blocking within this range; when EP 7 > 22 mm, 91% of SHAP values are positive, demonstrating a promotive effect. This occurs because once soil reaches water retention saturation39, subsequent precipitation cannot infiltrate further. Instead, it forms surface runoff that directly scours roadbeds and slopes, thereby triggering flood-damage blocking.

The SHAP value plot for temperature (Fig. 7c) reveals a pronounced nonlinear threshold effect, with a clear turning point at approximately 21 °C. Below this threshold, 92% of the samples exhibit negative SHAP values, indicating that temperature generally suppresses flood-damage blocking risk in this range. In contrast, when temperature exceeds 21 °C, 86% of the samples show positive SHAP values, suggesting that higher temperatures overall enhance flood-damage blocking risk. This threshold behavior is consistent with established physical mechanisms linking temperature to flood-related hazards. Elevated temperatures increase atmospheric moistur—holding capacity and convective activity, thereby raising the likelihood of extreme precipitation40. Temperature also affects soil moisture and antecedent wetness conditions, both of which play crucial roles in controlling surface runoff generation, landslide initiation, and debris—flow susceptibility during intense rainfall41. The SHAP dependence plot (Fig. 8) further supports these mechanisms. When temperature is below 21 °C, both precipitation and EP 7 remain at relatively low levels, jointly contributing to lower flood-damage blocking risk. When temperature exceeds 2 °C, however, high values of precipitation and EP 7 occur much more frequently, indicating that high—temperature conditions commonly coincide with strong rainfall and elevated antecedent wetness. Together, these analyses demonstrate that temperature influences flood-damage blocking risk primarily through its combined influence with precipitation and EP 7.

The ARSD factor represents the average road-stream distance within a 1-km radius. As shown in Fig. 7d, ARSD exhibits a clear threshold effect on flood-damage blocking risk. When ARSD is less than 0.15 km, 93% of the samples display negative SHAP values, indicating a relatively low likelihood of flood-damage blocking. In contrast, once ARSD exceeds this critical threshold, 98% of the samples show positive SHAP values, corresponding to a pronounced increase in flood-damage blocking risk. Spatial comparison with the slope map (Fig. 1) and the distribution of hydrographic lines, hydrographic polygons, and drainage density in Sichuan Province (Fig. 9) suggests that road sections close to rivers are generally located in relatively gentle terrains with weaker fluvial erosion, whereas road sections farther from rivers are more often situated in steep mountainous areas, which are more susceptible to secondary hazards such as landslides and debris flows during intense precipitation events42. Although slope is included as an independent predictor in the model, multicollinearity diagnostics indicate that ARSD and Slope are not strongly correlated (VIF ≤ 4; see Fig. S1in the Supplementary Material). Overall, these results indicate that ARSD effectively characterizes the threshold response of flood-damage blocking risk to road-stream distance and is valuable for identifying variations in road blockage risk.

Distribution of (a) hydrographic line, (b) hydrographic polygon, (c) and drainage density at the municipal level in Sichuan Province. The maps were generated and visualized using ArcGIS (version 10.7.0; https://www.esri.com), based on the hydrological data described in Table 1.

Model interpretability comparison

A comparison between the SHAP analysis results and the LR coefficients (Table 3) reveals a high degree of commonality in identifying meteorological factors. EP 7, precipitation and temperature ranked among the top four in both models, confirming that water-related factors exert a stable influence on the target variable.

However, the two models exhibit significant divergence in interpreting topographic factors: UBA and swamp demonstrated a strong influence on flood-damage blocking in LR (Rank 2 and Rank 5), whereas their contribution was significantly lower in the SHAP analysis (Rank 10 and Rank 11). A similar pattern is observed for ARSD. Although ARSD ranks highly in the SHAP analysis (Rank 3), its influence is relatively minor in the LR model (Rank 7).

This discrepancy can be attributed to two main factors. First, the SHAP is based on a MLP, which can capture nonlinear relationships between features and the target variable, whereas linear regression only considers linear effects. As a result, features with pronounced nonlinear effects may appear more important in SHAP than in LR, while features such as UBA and swamp, which exhibit strong linear relationships, may have their relative contributions diluted in SHAP. Second, ARSD exhibits a clear threshold effect (Fig. 7d). Such abrupt, non-linear contributions are difficult for LR to capture, but are effectively reflected by SHAP through its consideration of local and nonlinear feature contributions43.

Overall, these results suggest that while LR effectively identifies features with linear and additive effects, SHAP provides complementary insights by capturing nonlinearities and threshold-dependent influences, offering a more nuanced understanding of topographic factors in flood-damage blocking.

Conclusions

This study develops an integrated and interpretable framework for assessing highway flood-damage blocking risk by coupling time-series data augmentation, machine learning-based prediction, and disaster mechanism interpretation. Unlike conventional studies that rely on static indicators or linear assumptions, the proposed framework is specifically designed to address the temporal evolution, low occurrence frequency, and nonlinear interactions characterizing highway flood-damage blocking events, thereby enabling a more comprehensive representation of risk formation processes. Through a systematic comparison of multiple data-balancing strategies and predictive models, the results demonstrate that the MLP model trained on TimeGAN-augmented time-series data achieves the best overall performance, with an F1 score of 49.81% and a PR-AUC of 49.46%, exhibiting superior predictive accuracy and stability under imbalanced conditions.

SHAP interpretability analysis identified key drivers and their threshold effects. Daily precipitation exceeding 2.8 mm or EP 7 above 22 mm significantly increases the risk of highway blockage, while temperatures above 21 °C amplify the risk when combined with heavy precipitation and high EP 7. Additionally, ARSD greater than 0.15 km elevates the probability of blocking. Comparison between SHAP and LR coefficient results revealed that some terrain factors (e.g., UBA, swamp) have relatively low contributions in SHAP but high coefficients in LR, whereas hydrological factors like ARSD show the opposite pattern. These findings reflect the distinct feature attribution mechanisms of the models: SHAP captures nonlinear effects and reveals interaction patterns through dependence analysis, whereas LR only measures the linear independent effects of variables.

Overall, the identified key drivers and risk thresholds provide quantitative support for the development of flood damage early-warning systems, optimization of drainage facility design, and prioritization of flood-damage highway segments, thereby enhancing the overall resilience of road networks to flood damage.

Despite these contributions, this study has certain limitations. The model is developed based on a two-year dataset, which may be insufficient to fully capture long-term climatic variability and trends. In addition, the municipal-level spatial resolution and daily temporal resolution may constrain the representation of localized and short-duration hydrological processes. Future research should extend the temporal coverage to improve model stability and long-term risk analysis, incorporate higher spatial resolution data (e.g., county or grid-level), and integrate higher temporal resolution environmental variables (e.g., hourly rainfall and runoff indicators) to further enhance the accuracy and applicability of dynamic highway flood-damage blocking risk assessment.

Data availability

The public data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zheng, J. et al. Construction of an intelligent risk identification system for highway flood damage based on multimodal large models. Appl. Sci. 15, 12782 (2025).

Du, B. et al. Assessing the impact of precipitation variability on landslide hazards in urbanized regions. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 136, 104360 (2025).

Xin, Z. et al. The relationship between geological disasters with land use change, meteorological and hydrological factors: A case study of Neijiang City in Sichuan Province. Ecol. Ind. 154, 110840 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. A new method for calculating highway blocking due to high-impact weather conditions. Nat. Hazard. 25, 493–513 (2025).

Pan, J. et al. Characterizing China’s road network development from a spatial entropy perspective. J. Transp. Geogr. 116, 103848 (2024).

Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Communique on the Development of the Transportation Industry (2024). https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202506/t20250610_4170228.html (2025).

Zhang, W. et al. A year marked by extreme precipitation and floods: Weather and climate extremes in 2024. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 42, 1045–1063 (2025).

Smyl, D., Ghasemzadeh, F. & Pour-Ghaz, M. Modeling water absorption in concrete and mortar with distributed damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 125, 438–449 (2016).

Kringos, N. & Scarpas, A. Raveling of asphaltic mixes due to water damage. Transp. Res. Record: J. Transp. Res. Board 1929, 79–87 (2005).

Zeng, Y., Wang, Q., Cao, J. & Liu, G. (2020) Study on Water Damage Mechanism and Emergency Restore of Fill Subgrade upon Squashy Slope Foundation in Mountain Area. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 455: 012181.

Sun, D., Wen, H., Zhang, Y. & Xue, M. An optimal sample selection-based logistic regression model of slope physical resistance against rainfall-induced landslide. Nat Hazards 105, 1255–1279 (2021).

Mahmoud, A. A. et al. Synergizing machine learning and experimental analysis to predict post-heating compressive strength in waste concrete. Struct. Concr. 26, 2916–2950 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Spatiotemporal assessment of water damage susceptibility in China’s road infrastructure: a machine learning and SHAP approach using social media data. J. Hydrol. 664, 134539 (2026).

Wang, L. et al. Time series prediction of reservoir bank landslide failure probability considering the spatial variability of soil properties. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, 3951–3960 (2024).

Bashir, N. et al. Enhancing seismic activity classification in augmented soil gas radon time series data through computational intelligence techniques. J. Atmos. Solar Terr. Phys. 274, 106560 (2025).

EskandariNasab, M., Hamdi, S. M. & Filali Boubrahimi, S. Impacts of data preprocessing and sampling techniques on solar flare prediction from multivariate time series data of photospheric magnetic field parameters. ApJS 275, 6 (2024).

Wang, K., Yang, T., Kong, S. & Li, M. Air quality index prediction through TimeGAN data recovery and PSO-optimized VMD-deep learning framework. Appl. Soft Comput. 170, 112626 (2025).

Ali, R., Muayad, M., Mohammed, A. S. & Asteris, P. G. Analysis and prediction of the effect of Nanosilica on the compressive strength of concrete with different mix proportions and specimen sizes using various numerical approaches. Struct. Concr. 24, 4161–4184 (2022).

Zeyad, A. M. et al. Compressive strength of nano concrete materials under elevated temperatures using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 24246 (2024).

Mahmoud, A. A., El-Sayed, A. A., Aboraya, A. M., Fathy, N. & Nabil, I. M. Enhancing predictive accuracy of nano-additive concrete gamma ray attenuation at high temperatures using AI-based models. Neural Comput. Applic. 37, 21833–21866 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Regional sustainable development strategy based on the coordination between ecology and economy: A case study of Sichuan Province China. Ecol. Indicators 134, 108445 (2022).

Department of Transportation of Sichuan Province. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of the Transportation Sector in Sichuan Province (2023). https://jtt.sc.gov.cn/jtt/c101520/2024/10/15/5f5e139f8e8c4c4397440e0805e04bd9.shtml (2024).

Li, H. et al. A daily gap-free normalized difference vegetation index dataset from 1981 to 2023 in China. Sci Data 11, 527 (2024).

Bandara, C. M. M. Drainage density and effective precipitation. J. Hydrol. 21, 187–190 (1974).

China Meteorological Administration. Meteorological risk early warning levels of geological disaster induced by torrential rain. Standard QX/T 487–2019 (2019).QX/T 487—2019. (2019).

Yan, Y. et al. Spatial Distribution-based Imbalanced Undersampling. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35(6), 6376–6391. https://doi.org/10.1109/tkde.2022.3161537 (2022).

Chen, C., Wang, F., Wang, Z., Zhang, D. & Xiang, L. A novel flood forecasting model based on TimeGAN for data-sparse basins. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 39, 2267–2280 (2025).

Zhang, C. & Ji, D. HAL-Net: A historical analogy learning network for adaptive and interpretable pandemic forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 299, 130038 (2026).

Wang, L., Xiao, M., Lv, J. & Liu, J. Analysis of influencing factors of traffic accidents on urban ring road based on the SVM model optimized by Bayesian method. PLoS ONE 19, e0310044 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Multinomial random forest. Pattern Recogn. 122, 108331 (2022).

He, Z., Wu, Z., Xu, G., Liu, Y. & Zou, Q. Decision Tree for Sequences. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35(1), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1109/tkde.2021.3075023 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Driving risk prediction of urban arterial and collector roads using multi-dimensional real-time data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109386 (2024).

Betkier, I. Estimating travel time in transport network with a combined multi-attributed graph convolutional neural network and multilayer perceptron model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 142, 109898 (2025).

Wang, X., Jin, Y., Schmitt, S. & Olhofer, M. Recent Advances in Bayesian Optimization. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–36 (2023).

Fujiwara, K. Knowledge distillation with resampling for imbalanced data classification: Enhancing predictive performance and explainability stability. Results Eng. 24, 103406 (2024).

López-Oriona, Á. & Vilar, J. A. The bootstrap for testing the equality of two multivariate time series with an application to financial markets. Inf. Sci. 616, 255–275 (2022).

Fathy, I. N., Dahish, H. A., Alkharisi, M. K., Mahmoud, A. A. & Fouad, H. E. E. Predicting the compressive strength of concrete incorporating waste powders exposed to elevated temperatures utilizing machine learning. Sci. Rep. 15, 25275 (2025).

Pradhan, S., Toll, D. G., Rosser, N. J. & Brain, M. J. An investigation of the combined effect of rainfall and road cut on landsliding. Eng. Geol. 307, 106787 (2022).

Ashland, F. X. Critical shallow and deep hydrologic conditions associated with widespread landslides during a series of storms between February and April 2018 in Pittsburgh and vicinity, western Pennsylvania, USA. Landslides https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-021-01665-x (2021)

Sun, W., Li, J., Yu, R., Li, N. & Zhang, Y. Exploring changes of precipitation extremes under climate change through global variable-resolution modeling. Science Bulletin 69, 237–247 (2024).

Ran, Q. et al. The relative importance of antecedent soil moisture and precipitation in flood generation in the middle and lower Yangtze River basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 4919–4931 (2022).

Ye, S. et al. From rainfall to runoff: The role of soil moisture in a mountainous catchment. J. Hydrol. 625, 130060 (2023).

Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Gao, S. & Gu, X. Revealing nonlinear relationships and thresholds of human activities and climate change on ecosystem services in Anhui Province based on the XGBoost–SHAP model. Sustainability 17, 8728 (2025).

Funding

This research was generously funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFB4303100) on Integrated Technology Application for Autonomous Transportation Systems.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Li: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing; Lingyi Wu: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation; Jian Gao: Resources, Project administration; Feng Yang: Resources, Project administration; Yuqi Guo: Validation, Investigation; Mingyue Yan: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Wu, L., Gao, J. et al. Comparative analysis of machine learning models with SHAP interpretation for causes of highway flood-damage blocking. Sci Rep 16, 5118 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35074-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35074-8