Abstract

To compare healthy eyes to the fellow eyes of acute primary angle closure (F-APAC), healthy eyes to the fellow eyes of chronic primary angle closure glaucoma (F-CPACG), and these fellow eyes to each other (F-APAC vs. F-CPACG). This study included patients with PACG (72 eyes) and healthy individuals (22 eyes). Parameters were measured on ultrasound biomicroscopy images, including anterior chamber depth (ACD), anterior chamber width (ACW), anterior chamber area (ACA), lens vault (LV), relative position lens vault (RPLV), anterior segment depth (ASD), angle opening distance at 500 μm (AOD500), trabecular iris space area at 500 μm (TISA 500), trabecular iris angle at 500 μm (TIA500), iris thickness at 500 μm (IT500), peripheral iris thickness maximum (PITMAX), iris curvature (IC). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the most important parameters associated with F-APAC compared with F-CPACG. In total, 94 eyes of 94 patients were included. The ACD(P < 0.001), ACW(P < 0.018), ACA(P < 0.001), ASD(P = 0.006), AOD500(P < 0.001), TIA500(P < 0.001) and TISA500(P < 0.001) of the F-APAC were smaller than the healthy, and LV(P < 0.001), RPLV(P < 0.001), IC(P < 0.001) were larger than that. The ACD(P < 0.001), ACA(P < 0.001), ASD(P < 0.001), AOD500(P < 0.001), TISA500(P < 0.001) and TIA500(P < 0.001) of the F-CPACG were smaller than the healthy, and the LV(P < 0.001), RPLV(P < 0.001), PITMAX(P = 0.030), IC(P < 0.001) were larger than that. The LV(P = 0.027), AOD500(P = 0.013), TISA500(P = 0.03), TIA500(P = 0.006), IC(P = 0.48) of F-APAC were larger than F-CPACG, and PITMAX (P = 0.037) was smaller than F-CPACG. Multivariate logistic regression showed that only larger LV was significantly associated with APAC(P = 0.017). LV (AUC, 0.643) performed relatively in distinguishing the F-APAC and the F-CPACG. Anterior shift of the lens and iris bombe promoted the occurrence of APAC, thickening of the peripheral iris played vital roles in CPACG. Additionally, the LV was an important parameter to distinguish APAC or CPACG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have identified glaucoma as a leading cause of blindness worldwide1. In 2013, approximately 64.3 million individuals were affected by glaucoma, and this number is projected to increase to 110 million by 20402. Primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) refers to a group of disorders characterized by either acute or chronic elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP). These conditions may present with distinct optic disc changes and visual field defects3,4,5,6. In contrast to primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), PACG is to some extent preventable. Advances in medical imaging technology have enabled noninvasive detection of structural abnormalities in ocular tissues, including the corneal geometry, anterior chamber angle, iris, lens, ciliary body, and choroid7,8. Through qualitative and quantitative assessment of these ocular structures, we can identify and analyze the risk factors associated with the development of PACG. This information may provide a clinical basis for the early diagnosis and targeted treatment of PACG.

Current research on the anterior segment in PACG has primarily focused on eyes with active disease. However, it is important to note that the anterior segment structure of eyes with established PACG is often already significantly altered due to the effects of acute, intermittent, and chronic pathological processes. Since this is less helpful for early detection and differential diagnosis, we chose to focus on the contralateral uninvolved eyes of patients with PACG. By systematically observing the characteristics of these eyes and comparing them with the normal population, we hope to find out the different characteristics with diagnostic value. Therefore, this study aims to identify anatomical differences between the fellow eyes of patients with different subtypes of PACG and the eyes of healthy individuals, and to investigate the various factors involved in the pathogenesis of PACG.

Method

Research subjects

From January 2019 to December 2022, a total of 72 patients (72 eyes) diagnosed with PACG with a unilateral attack were enrolled in this study. The diagnostic criteria for PACG were based on the European Glaucoma Society Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma, 5th Edition (2021). All patients were recruited from the Affiliated Eye Hospital of Nanchang University and divided into two subgroups: the fellow eye of acute primary angle-closure (F-APAC) subgroup, comprising 42 patients (42 eyes), and the fellow eye of chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma (F-CPACG) subgroup, comprising 30 patients (30 eyes). Additionally, 22 healthy individuals (22 eyes) who underwent routine ophthalmic examinations at our hospital during the same period were selected as the control group. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Eye Hospital of Nanchang University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion criteria

PACG group: (1) Definite history of PACG in the fellow eye and no history of episodes in the examined eye, and IOP < 21 mmHg (2) Presence of anatomical features such as shallow anterior chamber and narrow anterior chamber angle (3) No optic nerve atrophy and Cup-to-Disc (C/D) ratio < 0.5 (4) No visual field defects. Healthy: (1) C/D less than 0.5 and bilateral C/D difference < 0.2 (2) Normal anterior chamber depth and full circumferential opening of the anterior chamber angle microscope (3) Normal visual field (4) No family history of glaucoma (5) Eye axial length ≤ 24 mm or refraction ≤ ± 1.00DS.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Refraction > ± 1.00DS or eye axial length > 24 mm (2) History of previous ocular laser iridotomy, laser iridoplasty and other intraocular surgery (3) History of previous ocular trauma or inflammation (4) Unable to cooperate with UBM examination or poor quality of UBM images and unrecognizable scleral spurs (5) Topical or systemic use of medications affecting anterior chamber structure (6) Secondary anterior chamber angle closure, such as lens dislocation, neovascular glaucoma.

General inspection

(1) All subjects were examined for uncorrected visual acuity and best corrected visual acuity; (2) Slit lamp ocular examination segment examination; (3) Non-contact tonometer IOP measurement: each subject received more than 3 IOP measurements, and the mean value was taken; (4) Gonioscopy; (5) Humphrey computerized visual field examination: the subjects were examined after corrective optometry using a 24 − 2 pattern. The mean defect (MD) and pattern standard deviation (PSD) were recorded. The false-positive rate < 20%, false-negative rate < 20%, and fixation loss rate < 20% were selected as the results. (6) OCT examination: The Zeiss Cirrus HD-OCT instrument was used to measure the RNFL thickness by selecting the Optic Disc 200 × 200 scanning mode for scanning;

UBM inspection

All subjects included in the study underwent UBM examination using a panoramic ultrasound biomicroscope (Suoer Electronic Ltd., Model SW3200L, China) with a scanning frequency of 50 HMz. The examination was conducted independently by an experienced operator.

All participants were positioned in a dark room, in the supine position, and received ocular surface anesthesia. An appropriately sized eye cup was selected and placed into the participant’s conjunctival sac, followed by the injection of normal saline into the eye cup as a coupling medium. Participants were instructed to fix their gaze straight upward with their fellow eye, while the transducer was maintained in a vertical orientation to acquire a complete image of the anterior ocular segment. The examination procedure should be carried out without putting pressure on the eyes. Scans were obtained of the superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal quadrants to ensure a comprehensive assessment.

Parameter measurement

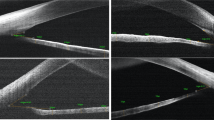

Based on the anterior segment parameter measurement methods reported in the literature9,10,11,12,13,14, clear UBM images were selected, and the measurement tools integrated into the software were used for precise measurements (Fig. 1). The parameters measured are as follows:

1. Anterior chamber depth (ACD): The distance from the inner surface of the cornea to the anterior surface of the lens.2. Anterior chamber width (ACW): The distance between the two scleral spurs.3. Anterior chamber area (ACA): The cross-sectional area enclosed by the inner surface of the cornea, the anterior chamber angle, the anterior surface of the iris, and the anterior surface of the lens. 4. Lens vault (LV): The vertical distance between the anterior surface of the lens and the horizontal line connecting the two scleral spurs.5. Relative position lens vault (RPLV): the ratio of lens vault height / (lens vault height and anterior chamber depth), reflecting the proportion of lens vault height in the anterior chamber. 6. Anterior segment depth (ASD): the sum of anterior chamber depth and lens vault height, reflecting the spatial size of the anterior chamber. 7. Angle opening distance at 500 μm, (AOD500): A straight line perpendicular to the inner surface of the cornea and intersecting with the anterior surface of the iris at 500 μm in front of the scleral spurs, the distance between the intersection of the line and the inner surface of the cornea and the anterior surface of the iris is defined as the angle opening distance. 8. Trabecular iris space area at 500 μm (TISA500): the area bounded anteriorly by AOD500, posteriorly by a line drawn from the scleral spur perpendicular to the plane of the inner scleral wall to the iris, superiorly by the inner corneoscleral wall, and inferiorly by the iris surface 9. Trabecular iris angle at 500 μm (TIA500): the angle between the inner surface of the trabecular meshwork and the anterior surface of the iris at 500 μm, with the scleral spurs as the apex. These three parameters directly reflect the contact between the iris and the trabeculae and are useful for understanding the degree of opening of the anterior chamber angle.10. Iris thickness at 500 μm (IT500): the thickness of the iris measured at 500 μm from the scleral spurs.11. Peripheral iris thickness maximum (PITMAX): the maximum thickness of peripheral iris. 12. Iris curvature (IC): the maximum vertical distance between the pupillary margin and the line connecting the iris root to the posterior surface of the iris, reflecting the degree of iris bulging.

To assess the repeatability and reproducibility of UBM measurements, 20 UBM images were randomly selected and remeasured by the same observer (G.L.). Intra-observer variability was evaluated with a 10-day interval between the two measurement sessions. Inter-observer variability was assessed by having a second observer (W.N.) independently measure the same set of 20 images. In addition, both observers were blinded to group allocation.

(a) ACD: anterior chamber depth; ACA: anterior chamber area; ASD: anterior segment depth. ACW: anterior chamber width; LV: lens vault. (b) PITMAX: peripheral iris thickness maximum; IC: iris curvature. (c) AOD500: angle opening distance at 500 μm; TISA500: trabecular iris area at 500 μm; TIA500: trabecular iris angle at 500 μm; IT500: iris thickness at 500 μm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 25.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean values of parameters measured in the superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal quadrants were calculated and used for the final analysis. Independent samples t-test was applied to compare continuous variables among the F-APAC, F-CPACG, and healthy control groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted for the F-APAC and F-CPACG groups to identify the most critical parameters that distinguish APAC from CPACG. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to evaluate the diagnostic value of relevant indicators, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to assess the correlation between anterior segment parameters and LV. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this study, a total of 94 eyes from 94 patients were included. Out of these, 42 were F-APAC patients, 30 were F-CPACG patients, and 22 were healthy. There were no significant differences observed in age, gender, IOP, Central Corneal Thickness (CCT), C/D ratio, and Axial length between the three groups (Table 1).

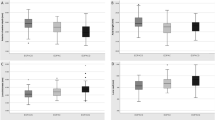

Independent samples t-test showed that ACD (P < 0.001), ACW (P < 0.018), ACA (P < 0.001), ASD (P = 0.006), AOD500 (P < 0.001), TISA500 (P < 0.001), TIA500 (P < 0.001) of F-APAC were significantly smaller than healthy, LV(P < 0.001) and RPLV(P < 0.001) of F-APAC were larger than healthy, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001), the differences of IT500 (P = 0.408) and PITMAX (P = 0.997) between the two groups were not statistically significant. ACD (P < 0.001), ACA (P < 0.001), ASD (P < 0.001), AOD500 (P < 0.001), TISA500 (P < 0.001), TIA500 (P < 0.001) of F-CPACG were significantly smaller than healthy, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001), LV (P < 0.001), RPLV (P < 0.001), PITMAX (P = 0.030), and IC (P < 0.001) were larger than healthy, the differences between the two groups in ACW (P = 0.195) and IT500 (P = 0.614) were not statistically significant. AOD500(P = 0.013), TISA500 (P = 0.03), TIA500 (P = 0.006), and IC (P = 0.48) of F-APAC were large than F-CPACG, and the difference was statistically significant, PITMAX (P = 0.037) was smaller than F-CPACG, and the difference was statistically significant, the differences between ACD (P = 0.414), ACW (P = 0.437), ACA (P = 0.075), RPLV (P = 0.072), ASD (P = 0.183), and IT500 (P = 0.790) were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that LV (P = 0.032), AOD500 (P = 0.017), TISA500 (P = 0.034), and TIA500 (P = 0.009) were significantly greater in the F-APAC than in the F-CPACG, while PITMAX (P = 0.034) was significantly smaller than in the F-CPACG (P < 0.05). After adjusting for covariates with P<0.05 (LV, AOD500, TISA500, TIA500, PITMAX) in the multivariate logistic regression analyses, only LV was left with significance (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The performance of LV as determinants for discrimination of F-APAC from F-CPACG was summarized in (Table 4), which showed AUC of 0.643. Among the parameters associated with LV, ASD (P = 0.002) and IC (P = 0.027) were positively associated with LV, while ACD (P = 0.003), ACA (P = 0.047) and IT500 (P = 0.026) were negatively associated with LV (Table 5).

Discussion

The anterior segment structure of PACG has been extensively investigated15,16. However, relatively fewer studies have focused on the fellow eye of PACG patients. Multiple studies have demonstrated that, beyond certain genetic factors, the development and progression of PACG are closely associated with anatomical structural alterations17,18,19,20. Although PACG is a bilateral ocular disease, the progression rate can differ between the two eyes. In clinical practice, it is observed that some patients present with PACG episodes in only one eye, while the fellow eye shows no evidence of optic nerve damage. Therefore, this study aims to explore the anterior segment structural characteristics of fellow eyes in PACG patients (F-PACG) and healthy controls. We also introduce a novel parameter termed the RPLV, which builds on prior research. While LV only reflects the degree of lens protrusion into the anterior chamber, RPLV provides a more intuitive measure of lens occupancy, representing the proportion of space occupied by the lens within the anterior segment. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has conducted a quantitative analysis of this parameter.

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between reduced ACD and an increased risk of PACG1. In the general population, the average ACD ranges from approximately 2.5 to 3.0 mm. Theinert et al.7 used ROC curves and the AUC to determine the optimal cut-off value for angle-closure disease, identifying that an ACD ≤ 2.1 mm is associated with an increased risk of acute angle closure (AAC)21. Furthermore, they found that the ACD in eyes with APAC was < 1.7 mm, which was smaller than that in eyes with CPACG; this suggests that an ACD < 1.7 mm may be a risk factor for APAC. Our study found that both the F-APAC and the F-CPACG had smaller ACD compared to the healthy, supporting previous findings. This indicates that PACG patients have a crowded anterior segment structure, with the smallest ACD in the F-APAC, the second largest in the F-CPACG, and the largest in the healthy. Identically, PACG patients experience a decrease in the ACA, also having a crowded anterior segment.

Lens-related factors play a critical role in the pathogenesis of PACG. An increase in LV leads to a larger contact area between the lens and iris, which enhances pupillary block—a key driver of PACG development and progression. Our study also revealed varying degrees of lens displacement in PACG patients; notably, the lens occupies a more anterior position in the ocular anterior segment, with this phenomenon being most prominent in the F-APAC group and less so in the F-CPACG group. Through multivariate logistic regression analysis, LV was identified as the only parameter that distinguishes APAC from CPACG. Additionally, ROC curve analysis showed that LV had an AUC of 0.643 (sensitivity = 0.844, specificity = 0.530), suggesting that the lens factor have a near-moderate importance in the anterior segment structure. A study using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) found that increased LV is a major determinant of APAC22. In APAC, higher LV increases contact between the lens and posterior iris surface, leading to elevated aqueous outflow resistance and a pressure gradient between the anterior and posterior chambers. This pressure gradient drives forward displacement of the peripheral iris, resulting in trabecular meshwork obstruction23. According to Allam et al.24, LV is a significant predictor of IOP reduction following lens extraction and has also been confirmed to contribute to PACG pathogenesis. However, a community-based randomized controlled trial suggested that widespread prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) for PACS eyes is not recommended, due to the low incidence of acute angle-closure attacks in PACS and the limited benefits of prophylactic LPI25. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that PACS eyes with high LV require special attention: high LV is a key risk factor for APAC and confers a high risk of acute attacks. Therefore, prophylactic LPI is recommended for these eyes to prevent acute angle-closure episodes.

The RPLV reflects the proportion of space occupied by the lens within the ocular anterior segment. A higher RPLV indicates a smaller available anterior chamber space, which increases the risk of developing PACG. We hypothesized that RPLV might be a more representative parameter for lens-related changes, as it quantifies the lens’s spatial proportion within the anterior segment. However, our final results demonstrated that LV—when used as an observational indicator—performed better than RPLV. Notably, the relatively small sample size of this study may have introduced bias into these results. Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to further investigate and validate our findings.

Regarding iris parameters, the IC reflects the degree of iris bulging. As iris dilation increases, the aqueous humor outflow channels narrow. A previous study identified a strong correlation between IC and LV. Consistent with this, our correlation analysis also revealed a significant association between IC and LV (R = 0.330, P = 0.027). An increase in LV exacerbates pupillary block, displaces the iris anteriorly, elevates posterior chamber pressure, and further enhances iris bulging. Compared with the F-CPACG group, the higher LV and IC in the F-APAC group suggest that iris bulging and pupillary block may be involved in the pathogenesis of APAC. Acute APAC episodes may occur when a pre-existing narrow anterior chamber angle closes suddenly, triggered by either external factors or anatomical changes in the eye. However, our study found no statistically significant differences in IT among the three groups, which is inconsistent with previous literature26. This discrepancy may be attributed to two factors: first, the eyes examined in the aforementioned literature had undergone LPI treatment; second, in some of our enrolled patients, the iris at 500 μm from the scleral spur was adherent to the anterior chamber angle. Angle closure in these cases caused compression and thinning of the iris at the 500 μm site, meaning the measured iris thickness did not reflect the true anatomical thickness. Notably, peripheral iris thickening appears to be a unique anatomical feature of F-CPACG patients. Furthermore, an increase in PITMAX exacerbates anterior chamber angle narrowing, leading to a transition from point contact to surface contact between the anterior chamber angle and the iris. This observation may explain why the anterior chamber angle is narrower in the F-CPACG group than in the F-APAC group.

Previous studies have identified AOD500, TISA500, and TIA500 as potential risk factors for anterior chamber angle closure. However, we propose that these parameters are not risk factors but direct indicators of anterior chamber angle closure. Thus, they can be effectively used to screen for PACG. Our study demonstrated a significant narrowing of the anterior chamber angle in PACG patients compared with healthy individuals. Furthermore, we observed that the degree of anterior chamber angle narrowing was more pronounced in patients with F-CPACG than in those with F-APAC. This finding was primarily attributed to the increased PITMAX in the F-CPACG group: thicker peripheral irides led to greater crowding of the anterior chamber angle. This effect is particularly prominent in eyes with specific morphological features (e.g., a narrow angle), where the peripheral iris is more likely to completely obstruct the trabecular meshwork27.

Objectively, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, we did not evaluate certain biological parameters related to dynamic iris changes—parameters that have been reported to be associated with angle closure. Third, our analysis focused solely on anterior segment structural changes; the posterior segment (e.g., the choroid and ciliary body) was not included in the assessment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the crystalline lens is more anteriorly positioned and the iris exhibits greater curvature in patients with APAC. This suggests that the development of APAC may be closely associated with abnormal positioning of the crystalline lens and the presence of iris bombe. In contrast, patients with CPACG have thicker peripheral irides, indicating that the primary pathogenesis of CPACG may involve anterior chamber angle narrowing caused by peripheral iris thickening. Additionally, increased LV is a key structural parameter that can distinguish between APAC and CPACG.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Teo, Z. L. et al. Six-Year incidence and risk factors for primary Angle-Closure disease: the Singapore epidemiology of eye diseases study. Ophthalmology 129 (7), 792–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.03.009 (2022).

Tham, Y. C. et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121 (11), 2081–2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013 (2014).

Jayaram, H., Kolko, M., Friedman, D. S. & Gazzard, G. Glaucoma: now and beyond. Lancet (London England). 402 (10414), 1788–1801. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01289-8 (2023).

European Glaucoma Society Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma, 5th Edition. British J. Ophthalmol. 105 (Suppl 1), 1–169. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-egsguidelines (2021).

Wang, Z., Wiggs, J. L., Aung, T., Khawaja, A. P. & Khor, C. C. The genetic basis for adult onset glaucoma: recent advances and future directions. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 90, 101066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101066 (2022).

Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhang, Y., Huang, S. & Zhong, Y. Differences and similarities between primary open angle glaucoma and primary angle-Closure glaucoma. Eye Brain. 16, 39–54. https://doi.org/10.2147/EB.S472920 (2024).

Theinert, C., Wiedemann, P. & Unterlauft, J. D. Laser peripheral iridotomy changes anterior chamber architecture. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 27 (1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000804 (2017).

Huang, W., Li, X., Gao, X. & Zhang, X. The anterior and posterior biometric characteristics in primary angle-closure disease: data based on anterior segment optical coherence tomography and swept-source optical coherence tomography. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69 (4), 865–870. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_936_20 (2021).

You, S. et al. Novel discoveries of anterior segment parameters in fellow eyes of acute primary angle closure and chronic primary angle closure glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (14), 6. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.14.6 (2021).

Shabana, N. et al. Quantitative evaluation of anterior chamber parameters using anterior segment optical coherence tomography in primary angle closure mechanisms. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 40 (8), 792–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02805.x (2012).

Wang, F., Wang, D. & Wang, L. Exploring the occurrence mechanisms of acute primary angle closure by comparative analysis of ultrasound biomicroscopic data of the attack and fellow eyes. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 8487907 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8487907 (2020).

Yan, C., Yu, Y., Wang, W., Han, Y. & Yao, K. Long-term effects of mild cataract extraction versus laser peripheral iridotomy on anterior chamber morphology in primary angle-closure suspect eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 108 (6), 812–817. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2022-322698 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Predictive equation for angle opening distance at 750µm after laser peripheral iridotomy in primary angle closure suspects. Front. Med. 8, 715747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.715747 (2021).

Guo, L. et al. Anterior segment features in neovascular glaucoma: an ultrasound biomicroscopy study. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 11206721241252476 https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721241252476 (2024).

Xie, Q. et al. Anterior segment OCT in primary angle closure disease compared with normal subjects with similar shallow anterior chamber. J. Glaucoma. 31 (2), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJG.0000000000001915 (2022).

Loo, Y. et al. Association of peripheral anterior synechiae with anterior segment parameters in eyes with primary angle closure glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 13906. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93293-7 (2021).

Senthilkumar, V. A., Pradhan, C., Rajendrababu, S., Krishnadas, R. & Mani, I. Comparison of uveal parameters between acute primary angle-closure eyes and fellow eyes in South Indian population. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70 (4), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_1561_21 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Analyzing anatomical factors contributing to angle closure based on anterior segment optical coherence tomography imaging. Curr. Eye Res. 47 (2), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2021.1978098 (2022).

Xu, B. Y. et al. Ocular biometric risk factors for progression of primary angle closure disease: the Zhongshan angle closure prevention trial. Ophthalmology 129 (3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.10.003 (2022).

Panda, S. K. et al. Changes in Iris stiffness and permeability in primary angle closure glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (13), 29. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.13.29 (2021).

Yoshimizu, S., Hirose, F., Takagi, S., Fujihara, M. & Kurimoto, Y. Comparison of pretreatment measurements of anterior segment parameters in eyes with acute and chronic primary angle closure. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 63 (2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-019-00651-0 (2019).

Guzman, C. P. et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography parameters in subtypes of primary angle closure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54 (8), 5281–5286. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12285 (2013).

Quigley, H. A., Friedman, D. S. & Congdon, N. G. Possible mechanisms of primary angle-closure and malignant glaucoma. J. Glaucoma. 12 (2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/00061198-200304000-00013 (2003).

Allam, R. S., Raafat, K. A. & Elmohsen, M. N. A. Nasal trabeculo-ciliary angle and relative lens vault as predictors for intraocular pressure reduction following phacoemulsification. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32 (5), 3019–3028. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721211055033 (2022).

He, M. et al. Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London England). 393 (10181), 1609–1618. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32607-2 (2019).

Chen, H. J., Wang, X., Yan, Y. J. & Wu, L. L. Postiridotomy ultrasound biomicroscopy features in the fellow eye of Chinese patients with acute primary angle-closure and chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma. J. Glaucoma. 24 (3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJG.0000000000000086 (2015).

Wang, B. S. et al. Increased Iris thickness and association with primary angle closure glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95 (1), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2009.178129 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Liang Guo, Yan Wu, Na Wang, Qingyi Liu, Zhimin Shen, and Lu Yang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Liang Guo, Yan Wu and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Eye Hospital of Nanchang University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, L., Wu, Y., Wang, N. et al. Differences of anterior segment features in fellow eyes of primary angle closure glaucoma and healthy eyes. Sci Rep 16, 5135 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35075-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35075-7