Abstract

In the context of today’s global ecological and environmental crises and challenges, environmental education is a super important for achieving sustainable development. Traditional environmental education often suffers from superficial understanding of environmental information and a lack of depth in environmental awareness. The purpose of this study is to guide students towards a deep cognition of environmental information and to enhance environmental awareness, while exploring the pathways. The study establishes a Site-scale Ecological Virtual Laboratory (SEVL) on the campus. Based on the Game-Based Learning (GBL) model, the study introduces three mediators: self-efficacy, learning motivation, and cognitive load, to construct a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM). The data for this study were collected from 146 Chinese students majoring in landscape architecture. According to the analysis results derived from PLS-SEM, we confirm that: (1) SEVL can effectively intervene in environmental education; (2) SEVL influences learning motivation which subsequently affects self-efficacy, ultimately leading to positive outcomes in environmental education (β = 0.040, p < 0.05, 95%CI[0.018,0.094]); (3) SEVL impacts cognitive load which then influences self-efficacy, resulting in effective outcomes in environmental education (β = 0.048, p < 0.05, 95%CI[0.012,0.088]). The study provides a reference for leveraging virtual laboratory in environmental education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past century, human activities have exploited and depleted natural resources, leading to a disruption of the internal balance of nature. This has resulted in issues such as resource exhaustion and extreme weather events, which pose significant threats to human safety and sustainable development1,2,3. The future generation must possess adequate environmental knowledge to address challenges and make ethical, effective decisions. They need to become individuals equipped with scientific reasoning and a sense of environmental responsibility, providing solutions for the sustainable development of the Earth4. Environmental education is a crucial means to achieve sustainable development5,6. In the 1970s, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) established clear objectives for environmental education. These objectives aim to assist individuals in recognizing values, interpreting relevant concepts, understanding the interactions between humans and their environment, and acquiring the necessary skills and attitudes for this process7,8,9,10. In other words, environmental education aims to assist individuals in understanding environmental information and to guide them in developing a positive environmental awareness11,12,13, thereby laying the foundation for sustainable development.

Numerous studies have shown that environmental education equips individuals with essential knowledge about the environment, enhancing their understanding of the root causes of environmental problems. This contributes to the development of positive perceptions and attitudes toward nature6. For instance, integrating environmental courses into university education can effectively disseminate knowledge about waste classification14,15 and the use of plastic products16,17, thereby enhancing students’ environmental knowledge and awareness. Employing methods such as green advertising and ecological labeling in environmental education enables consumers to understand organic products, solar energy products, and other green offerings, ultimately increasing their purchasing inclination18,19,20. Additionally, through various approaches such as natural contact21, field research22, and outdoor classrooms23, individuals can acquire knowledge about ecosystems and sustainability during the learning process, thereby fostering a positive attitude towards the environment. Overall, environmental education serves as an effective strategy for addressing environmental issues by enhancing individuals’ cognition of environmental information and fostering a greater consciousness of ecological concerns24,25.

Current environmental education methods are evolving in diverse ways. These include traditional classroom instruction26,27,28,29 and written communication18,19,20, focusing on the efficient transmission of environmental concepts, facts, and norms, which is the key to laying the cognitive foundation. Additionally, experiential learning, which emphasizes experiential and practice oriented, has been widely applied30. They help students connect abstract knowledge with concrete situations through direct or simulated practical experience. With the development of digital technology, digital learning is becoming increasingly popular31,32. Its immersion and interactivity provide possibilities for simulating complex environmental systems and visualizing abstract processes, and are regarded as powerful tools for cultivating deep cognition. Learners must develop a deep understanding of environmental information33,34.

In existing research, General Environmental Knowledge (GEK) refers to an individual’s understanding of ecological processes, biodiversity, natural resources, and human-environment interactions35. It covers scientific, social, economic, and cultural dimensions of the environment36. Higher levels of GEK often lead to more positive environmental attitudes37. Building on this, the present study defines the deep understanding of environmental information across three dimensions: breadth, depth, and accuracy38. The breadth of environmental information refers to a truthful and comprehensive and objective representation of environmental characteristics, rather than merely considering a one-sided perspective. Detail refers to the complete features of the environment through data simulations that show us how things change over time. This helps us grasp the complexity of our surroundings, which is often called accuracy. Depth involves comprehending the mechanisms and rules on environment, enabling humans to undertake complex analyses and design tasks related to it39,40.

However, in many educational contexts, classroom teaching and written communication remain the primary methods41. These approaches mainly present conceptual knowledge. They often fail to provide environmental information with sufficient breadth, depth, and accuracy. This is especially true in the absence of scientific instruments, quantitative data42, and spatial experiences41. Under such conditions, learners often rely on intuitive feelings to make environmental judgments. Their understanding thus remains at a relatively superficial level. This limited depth of understanding struggles to support the lasting development of environmental ethics and ecological responsibility. Therefore, it is necessary to explore digital tools. Such tools should enhance learners’ deep understanding of environmental information and raise their environmental awareness. This exploration would further enrich the teaching methods used in environmental education.

According to previous research, virtual laboratory can provide solutions for this issue. Virtual laboratory offer immersive simulations of real-world systems and processes43. They use data acquisition systems and visualization tools44,45,46 to measure, identify, and analyze environmental parameters. This enables the interpretation of complex environmental factors and quantifies the ecological relationships within the site47,48,49. This approach enables learners to gain an in-depth understanding of their surrounding environment32,50,51. Comparative experiments can further confirm the ability of virtual laboratory to enhance environmental awareness, increase intentions for action, and promote pro-environmental behaviors48,52. Additionally, extensive research widely confirms that virtual environment offers novel interaction methods and provides a simulated representation of abstract elements53. Its characteristics, such as immersion and interactivity, can influence students’ self-efficacy54, cognitive load55,56, and learning motivation57,58, thereby enhancing learning outcomes.

However, existing research on the impact of virtual laboratory in environmental education reveal a notable theoretical gap. On one hand, numerous studies focus on application development and efficacy validation. Their goal is primarily to prove whether virtual laboratory effectively enhances environmental knowledge, attitudes, or behavioral intentions59. On the other hand, researches into influencing factors—such as learning motivation and self-efficacy—often targets general learning outcomes. These studies typically lack a theoretical framework linking these factors to the specific objective of deepening learners’ cognitive understanding of environmental information. To date, few studies have employed an integrated framework combining learning motivation, cognitive load, and self-efficacy. This framework is needed to explain how virtual laboratory influences learners’ cognitive processing. Such an explanation would clarify how these tools subsequently promote a deeper understanding of environmental information cognition and environmental awareness. This shortcoming leaves the mechanisms through which virtual laboratory function in environmental education inadequately explained and persists a clear theoretical gap in this area of research.

In summary, the study suggests that virtual laboratory can assist learners in achieving a deep cognition of environmental information and an enhancement of environmental awareness, effectively overcoming the cognitive limitations in traditional environmental education. However, the mechanisms through which these benefits are realized require further exploration. Therefore, this research is grounded in the campus environment—an accessible context for students—and aims to construct a Site-scale Ecological Virtual Laboratory (SEVL) based on Game-Based Learning (GBL) model60. Utilizing Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM), the study reveals the mechanisms by which the SEVL facilitates deep cognition of environmental information and enhances environmental awareness.

The core issues addressed by this research include:

(1) The construction of a Site-scale Ecological Virtual Laboratory, which can guide students towards a deep cognition of environmental information and to enhance environmental awareness.

(2) An investigation into the mechanisms through which it exerts its effects.

Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

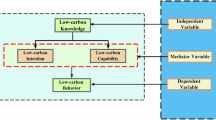

The study is based on the “Game-Based Learning (GBL)” Model proposed by Garris et al.60. The model’s “input-process-output” structure is a universal concept based on the GBL60 that helps explain how gamified learning works. In the GBL framework, the input phase involves a teaching program embedded with interactive features typical of games. These game elements initiate a user–system interaction loop. During the process phase, users start to experience changes in their behavior or mindset, leading to a self-motivated learning process. Ultimately, this will lead to the output phase where learning outcomes are achieved60.

The GBL framework effectively conceptualizes the mechanism by which “educational interventions influence learners’ experiential processes, thereby generating learning outcomes61.” This framework is particularly applicable to the present study, because it emphasizes the core mechanism of triggering the learning process through gamified experiences (i.e., virtual laboratory) to enhance learning outcomes.

In this study, the input phase refers to SEVL, which is a gamified environment featuring interactivity, immersion, and feedback mechanisms. It serves as a platform for delivering educational content in an engaging way. The process phase focuses on the learning process triggered by SEVL. Based on the internal logic of this process phase and the characteristics of SEVL, the research brings in self-efficacy, cognitive load, and learning motivation as key mediating factors in the entire process. Specifically:

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s judgment of their ability to organize and execute specific tasks. It is a critical psychological factor that affects how people face and engage with learning challenges62. SEVL can help strengthen students’ self-efficacy beliefs by providing a realistic yet low-risk environment for practice63. In a virtual environment, the reduced cost of trial and error allows students to build their skills without facing real consequences64. This can alleviate anxiety, making them more likely to actively explore and develop a deeper understanding of the learning material65, thereby demonstrating stronger higher-order cognitive abilities during the learning process66.

Moreover, SEVL can effectively simulate real-world situations and provide a rich learning experience. Through interactive and gamified features, it fosters students’ motivation to learn67,68. Driven by intrinsic motivation, students are more likely to stick with challenges and are willing to tackle problems or complete tasks in a game-like setting69. It is widely recognized that students’ motivation significantly influences their performance in school, encompassing aspects such as attention, effort level, quality of work, behavior and exam scores70,71. Research in educational psychology has also demonstrated a positive correlation between intrinsic motivation and academic achievement72. Furthermore, intrinsic motivations—such as interest in the subject matter—can substantially strengthen students’ self-efficacy beliefs, enabling them to tackle more challenging tasks73.

The SEVL can effectively integrate knowledge into learning contexts, thereby reducing the complexity of interactions between students and learning materials74. This integration reduces cognitive effort and alleviates cognitive load, facilitating the achievement of incremental successes. Throughout this process, it reinforces learners’ confidence75,76 and enhances their sense of self-efficacy.

However, although the importance of self-efficacy, learning motivation, and cognitive load in virtual learning environments has been recognized, existing research has limitations in terms of research frameworks. Many studies tend to treat these three factors as parallel and independent mediating variables77,78, testing their respective pathways of action, ignoring the interaction relationship between the three. For instance, Wu analyzed large-scale datasets to explore the relationship between students’ intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy79. Their findings suggest that intrinsic motivation—stemming from interest in the subject itself—can significantly enhance students’ self-efficacy. This increased self-efficacy, in turn, enables them to tackle more challenging tasks73. Conversely, Bishara argues that increased cognitive load can undermine students’ self-efficacy, lower cognitive load, on the other hand, helps strengthen their confidence in completing tasks80.

Overall, the empirical conclusion proves that the interplay among self-efficacy, cognitive load, and learning motivation acts as a set of mediating mechanisms in determining the effectiveness of SEVL. SEVL enables students to actively engage with content through interactive simulations and authentic performance tasks, helping them have the best immersive experience possible81. In this process, it stimulates learning motivation and optimizes cognitive load to enhance learning experience, further boosting self-efficacy and creating a positive feedback loop.

Therefore, to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanism by which SEVL promotes deep environmental cognition, it is necessary to go beyond testing single mediating effects and construct an integrated framework that reflects the synergistic effects of these variables. The process stage of this framework are designed to address this limitation, explicitly positioning self-efficacy, learning motivation, and cognitive load as core interrelated elements within the process stage, and assuming a clear path relationship between them.

The output phase refers to the enhancement of deep cognition of environmental information and the enhancement of environmental awareness. A deep understanding of the environment provides essential information for comprehending environmental issues and directly shapes awareness of these problems82. Environmental awareness encompasses a deep understanding of the interactions between human activities and environment, as well as attention to and reflection on the resulting environmental problems. This awareness is shaped by individuals’ values, knowledge, and experiences related to environment83,84.

Based on this framework, this study proposes the following more specific hypotheses:

H1: The SEVL will influence learning motivation.

H2: The SEVL will influence self-efficacy.

H3: The SEVL will influence cognitive load.

H4: Learning motivation will influence self-efficacy.

H5: Cognitive load will influence self-efficacy.

H6: Learning motivation will influence deep cognition of environmental information.

H7: Self-efficacy will influence deep cognition of environmental information.

H8: Cognitive load will influence deep cognition of environmental information.

H9: Deep cognition of environmental information will influence the enhancement of environmental awareness.

The final framework for this research is shown in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Figure 2 illustrates the experimental procedure of this study. The objectives of environmental education should shift from superficial cognition to a deeper understanding of environmental information and an enhancement of environmental awareness. With this goal, the research designed the SEVL. Following the research hypothesis framework (Fig. 1), we adopted a single-group post-test design and collected data through a questionnaire survey. After conducting the experiment, we employed PLS-SEM and using SmartPLS 4.0 to validate research model and test our hypotheses, thereby exploring how SEVL facilitates students’ deep cognition of environmental information and enhances their environmental awareness.

SEVL’s construction objectives and design

The SEVL aims to assist students in developing a deep cognition of environmental information and enhancing environmental awareness. Figure 3 illustrates our interpretation of these two objectives and how SEVL can achieve them.

The cognition of environmental information encompasses not only breadth but also detail and depth38. In terms of breadth, students should be able to identify various environmental factors and understand their interconnections. Regarding accuracy, students should grasp environmental data and quantitative relationships. Finally, in depth, students need to explain the causal chains and dynamic processes within ecosystems.

Therefore, SEVL highlights the breadth, accuracy, and depth of environmental information cognition. This study developed an SEVL model based on CAD drawings and Unity 3D to ensure a realistic and comprehensive reflection of environmental characteristics(Fig. 4). We’ve done multiple measurements on-site for landscape elements, environmental factors, and design goals (like human comfort levels). Using the random forest algorithm, we calculated the ecological relationships among these three types of data. Once linked to SEVL, it allows us to simulate data that shows how the environment changes over time—this helps with accuracy. There are several design goals within SEVL. Students need to keep adjusting based on their understanding of these ecological relationships as they tackle complex environmental analysis and design tasks—demonstrating depth in their cognitive processes.

SEVL’s simulation plot model. Data source: original aerial photographs captured by the authors using a DJI Mavic 3T drone. Image processing and map creation: the site map was processed and visually edited using Adobe Photoshop 2020 (Adobe Inc., https://www.adobe.com).

The part about environmental awareness in SEVL comes from four people who have made significant contributions from an environmental perspective: Alexander von Humboldt proposed that “nature is an organic whole, where everything is interconnected85”. Ian McHarg regarded the environment as a process, emphasizing the understanding of natural processes and the interactions among environmental elements86. John Lyle pointed out that behind landscape scales lies a continuously operating ecological order87. Frederick Steiner further underscored the ecological efficacy of surrounding site-scale environments, suggesting that sites should emulate natural systems to create “working landscapes”88. Overall, humanity’s environmental awareness has evolved through a series of processes, transitioning from an understanding of natural integrity to systemic interconnections, towards cognitive order within environments, and realization of landscape functions.

Environmental awareness is integrated into SEVL’s cognition of environmental information. During the process, the gathered environmental information will help students better understand their surroundings, which in turn boosts their awareness of environmental issues.

Experimental procedure

This research process is divided into four steps: experimental participants and procedure, operating SEVL, collecting experimental data, and conducting data analysis (Fig. 5).

Participants and procedure

This study requires a foundational understanding of environmental and ecological disciplines. Therefore, it is conducted based on the course Fundamentals of Ecology offered by Landscape Architecture major from an agricultural university in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China. This study requires a foundational understanding of environmental and ecological disciplines. Therefore, it is conducted based on the course Fundamentals of Ecology offered by Landscape Architecture major from an agricultural university in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China. Prior to conducting the questionnaire survey, we sought and obtained ethical approval from an academic institution. The research practices adhered to established ethical guidelines and secured verbal informed consent from all participants. Before collecting data, we spent 6 weeks explaining the SEVL principles and another 2 weeks going over how to operate SEVL. Once we were confident that everyone could use it properly, we conducted a 2-hour hands-on SEVL experiment followed by gathering responses through an online questionnaire.

A total of 153 students participated in this study. Ultimately, we obtained 146 valid datasets (43.8% male; average age = 19.5).

The SEVL’s operational procedure

After accessing SEVL through computers, students develop an initial understanding of landscape elements and ecological factors within the experimental scenario. Based on site conditions, SEVL has established five design objectives: stormwater management, biodiversity conservation, temperature regulation, air quality enhancement, and noise reduction. Students can select a design objective to make adjustments and optimizations. The intrinsic relationships between landscape elements and ecological factors are displayed in real-time data format according to algorithmic models. Upon achieving the design objectives, students will be able to evaluate their design outcomes by comparing indicators before and after adjustments. This helps students check whether their plans are feasible and makes it easier for them to move from just tweaking surface parameters to really grasping deeper ecological relationships (Fig. 6). The experiment took a total of 2 h. The environmental information accumulated during the experimental process will enhance students’ awareness of environmental issues, thereby serving as cognitive support for improving environmental awareness.

Measures

This study’s measurement indicators encompasses six dimensions: Site-scale Ecological Virtual Laboratory (SEVL), learning motivation (LM), self-efficacy (SE), cognitive load (CL), deep cognition of environmental information (EI) and enhance environmental awareness (EA)—totaling 29 items. We utilized a five-point Likert scale89, where 1 indicates “strongly disagree” and 5 indicates “strongly agree”. All items included in the questionnaire are presented in supplementary file.

SEVL: This subscale assesses the factors related to SEVL that may influence the learning process and learning outcomes. Davis90 proposed the widely accepted Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which posits that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are two key beliefs determining an individual’s intention to utilize a particular technology. In this study, we’re focusing on perceived usefulness because students have already spent 8 weeks learning about SEVL principles and how to use it, giving them plenty of hands-on experience. A lot of researches91,92 shows that when people get pretty good at using a technology, the effect of perceived ease of use on their attitudes and intentions tends to weaken or even become insignificant. Therefore, this research adapted Davis’s90 scale for perceived usefulness specifically for SEVL usage. This subscale includes 4 questions. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.908.

Learning motivation (ML): This subscale is adapted from the ‘Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)’developed by Printrich et al.93 and Crede and Phillips94. It encompasses three primary dimensions: value, expectancy, and affect. The subscale consists of four items. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.874.

Self-efficacy (SE): This subscale is based on the self-efficacy theory proposed by Bandura95 and Printrich and Schunk96. The self-efficacy component can be divided into five aspects: attitudes towards learning setbacks, achievement of learning goals, perceptions of learning challenges, current learning conditions, and understanding of self-learning prerequisites. This subscale comprises a total of five items. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.906.

Cognitive load (CL): This subscale is adapted from the “Cognitive Load Scale” developed by J. Leppink and F. Paas97, which investigates three types of cognitive load: intrinsic load, extraneous load, and germane load. The subscale consists of three items. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.915.

Deep cognition of environmental information (EI): This subscale aims to assess whether students achieve a deep cognitive understanding of environmental information after using SEVL. To ensure its relevance and effectiveness, the questionnaire items were designed based on the learning content and objectives outlined in SEVL. The framework of the questionnaire is divided into three components: breadth, accuracy, and depth of environmental information. Two professors in related major were invited to review and revise the items to enhance their validity. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.947.

Enhance environmental awareness (EA): This subscale aims to assess whether students’ environmental awareness can be enhanced after utilizing SEVL. The questionnaire items for this subscale are designed based on the learning content and objectives outlined in SEVL. The framework of the questionnaire is divided into four sections: holistic nature, systemic relevance, cognitive environmental order, and realization of landscape functions. Two professors in related major were invited to review and revise the items to enhance their validity. The Cronbach’s α value for this scale is 0.916.

The research used an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the scale, and found that the KMO value is 0.898. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 (300) = 3546.777, p < 0.001). Therefore, both of these indicators meet the minimum standards required for subsequent data analysis.

The analysis employed principal component analysis (PCA) combined with variance maximization rotation, ultimately extracting six key factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. These factors collectively account for 76.89% of the total variance (Table 1). From the rotated component matrix, it is evident that all items exhibit loadings exceeding the standard threshold of 0.7 on their respective factors, and there are no issues of cross-loadings. This indicates that each factor possesses a clear meaning and demonstrates good internal consistency, resulting in an exceptionally ideal factor structure (Table 2).

The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s α, which ranged from 0.874 to 0.947. All values significantly exceeded the threshold of 0.7, indicating that both the questionnaire and its components can be considered reliable. Therefore, data collection for this study was conducted based on this questionnaire.

Data analysis methods

This study used SPSS 26.0 to generate box plot is used for descriptive analysis. The median and interquartile range (IQR) are employed to indicate the central tendency of the scores, with the box range reflecting the distribution interval of the core 50% of the data and the whisker direction indicating data skewness. If the majority of sub-dimension medians approach the upper limit of the scale ≥ 4 and the IQR is ≤ 1.0, the data is considered highly concentrated, indicating effective functionality and group consistency98,99,100.

The research assessed and validated the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the potential constructs. Convergent validity and reliability were evaluated based on three criteria101: factor loadings (> 0.70), composite reliability (> 0.70), and average variance extracted (AVE > 0.50). Discriminant validity was examined using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio (< 0.90), cross-loadings102, and the Fornell-Larcker criterion[103]. Following the validation of the measurement model, we employed PLS-SEM to test the structural model and hypotheses. The PLS-SEM method is a well-established multivariate analysis technique104 that allows for estimating complex models comprising multiple constructs, indicator variables, and structural paths without making assumptions about data distribution103. Additionally, PLS-SEM is suitable for small sample sizes when models contain numerous constructs and items105. Therefore, PLS-SEM serves as an effective approach for exploratory research, providing the necessary flexibility for interaction between theory and data106.

We determined the minimum sample size for the PLS-SEM model according to the 10-times rule. Specifically, the sample size should exceed ten times the maximum number of internal or external model links pointing to any latent variable within the model107. Based on this rule, a minimum of 90 observations (9 × 10) is required to estimate the PLS path model. Therefore, considering this method, the 146 valid questionnaires collected in this study are deemed sufficient.

We utilized SmartPLS 4.0 for validation and hypothesis testing of PLS-SEM. The evaluation of PLS-SEM results involves examining both the measurement model and structural model. Detailed results will be discussed in the following section.

Results

Descriptive analysis of core dimensions

This study uses SPSS 26.0 to conduct descriptive analysis of core dimensions through box plots (Fig. 7). The evaluations of EI are comprising nine sub-dimensions in total (EI1-EI9), covering three sub-dimensions: granularity (EI1), accuracy (EI2-EI4), and depth (EI5-EI9). The box plot results show that the medians of most boxes are concentrated between 4 and 5, indicating high student agreement of the SEVL’s ability to get a deep cognition of environmental information. The IQR of the majority of the box plots is 1.0, indicating a high degree of data concentration. This suggests that students perceive the functionality of deep cognition of environmental information as effective and consistent across the group. Among the three sub-dimensions related to precision (EI2 - EI4), potential low-score outliers were identified in both EI2 and EI4, while EI3 exhibited an IQR of 2.0. This indicates that some students are difficult in understanding the ecological relationships between landscape elements and environmental factors through SEVL during specific tasks.

The Fig. 7 also displays students’ evaluations of the SEVL’ s ability to enhance environmental awareness (EA1-EA4), covering four dimensions: natural integrity (EA1), systemic interconnections (EA2), cognitive order within environments (EA3), and realization of landscape functions (EA4). The results show that the medians of all dimensions are 5, indicating significant effectiveness of the SEVL in enhancing environmental ethical awareness. The IQR is = 1.0, reflecting highly concentrated data, which suggests that students perceived the functionality of enhancing environmental awareness as effective and consistent across the group. Overall, students’ evaluations of the SEVL’s ability to enhance environmental awareness are highly positive.

Overall, students rate the SEVL highly in terms of deep cognition of environmental information and enhanced environmental ethical awareness, indicating that the SEVL effectively breaks through superficial cognitive patterns and facilitates the internalization of environmental ethical awareness.

Measurement model

Convergent validity

Following the standards set by Hair et al.108 and Asadi et al.109, we primarily assessed the validity of the measurement model through reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. As shown in Table 3, all Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients (CA) exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating that the scale demonstrates good reliability. The Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.885 to 0.948, all surpassing the suggested minimum of 0.70110. Convergent validity was evaluated using Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with all latent variables exhibiting AVE values greater than 0.5, thereby confirming the effectiveness of the measurement model108,111.

Furthermore, the acceptable level of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should exceed 0.5112. In this study, all estimated AVE values for the constructs (Table 3) exceed 0.50. These findings indicate that the measurement model demonstrates both convergent validity and internal consistency. This suggests that the measurement items effectively assess each construct without any interference from other constructs within the research model112.

A high outer loading for a construct signifies a strong relationship among its associated items. Elevated outer loadings imply close connections between key components of each construct. Generally, items with very low outer loadings (below 0.4) should be routinely removed from the scale103. Table 3 presents the outer loadings for all measurement models; thus, all reported outer loadings are deemed acceptable.

Discriminant validity

The concept of discriminant validity refers to “the extent to which a construct is empirically distinct from other constructs within a structural model103.” When employing the Fornell-Larcker criterion (a traditional metric), this method requires that the square root of each latent variable’s AVE must exceed the correlations between that variable and all other variables (Table 4). The testing results meet the standards set forth by Fornell and Larcker.

When the indicator loadings of a construct exceed their cross-loadings with other constructs, discriminant validity can be established108. Table 5 presents the outer loadings of all indicators along with their cross-loadings with other indicators. It is evident that the outer loading for each construct is greater than its overall cross-loading with other constructs. Based on the results from the assessment of cross-loadings, it can be concluded that discriminant validity has been established through the evaluation of outer loadings.

When the HTMT value exceeds the threshold, issues related to discriminant validity may arise. HTMT values above 0.90 indicate a lack of discriminant validity108. As shown in Table 6, all values are below 0.90. The results indicate that all HTMT values significantly differ from 0.9, thereby establishing the discriminant validity of the construct.

Path model validation

This study employs the bootstrapping resampling method to predict the statistical significance of the PLS path model. This approach necessitates a minimum requirement of 5,000 bootstrap subsamples for model analysis113,114. Therefore, this study employs 5,000 bootstrap subsamples to examine the relationships among the various latent variables proposed in the research model. The p-values and t-values are utilized to assess whether the path coefficients hold statistical significance, with a significance level set at 5%. Specifically, when the p-value is less than 0.05, it supports the research hypotheses115. Table 7 presents the results of multiple hypothesis tests. Based on the results of the bootstrapped PLS-SEM analysis, we have identified support for nine hypotheses.

The final model of this study is illustrated in Fig. 8. The empirical results indicate that SEVL has a positive and significant impact on both learning motivation and cognitive load. Furthermore, learning motivation and cognitive load positively and significantly influence self-efficacy. Self-efficacy, learning motivation and cognitive load, exerts a positive and significant effect on deep cognition of environmental information. Lastly, deep cognition of environmental information positively and significantly enhances environmental awareness.

Additionally, Table 8 displays the indirect effectsof the latent variables and several important mediating paths. Based on these results, it can be inferred that for the SEVL to achieve the effects of EI and EA, three mediating variables are involved: CL, LM, SE.

Discussion

This study successfully established the SEVL. The results of the PLS-SEM analysis indicate that SEVL can significantly and positively influence students’ deep cognition of environmental information through a series of mediating pathways, thereby enhancing their environmental awareness. This finding confirms the effectiveness of VR in improving learning outcomes, aligning with the principles underlying Virtual Geographic Environments (VGE).

According to Lin et al.116, a Virtual Geographic Environment (VGE) is defined as “a workspace for computer-assisted geographic experiments (CAGEs) and geographic analysis,” with its core focus on supporting geographic visualization, simulation, collaboration, and human engagement. The SEVL constructed in this study essentially serves as a site-scale VGE tailored for environmental education. SEVL builds upon and extends the functionalities of VR—primarily aimed at creating spaces rich in geometric and physical attributes117—by directing its objectives towards mapping environmental information related to dynamic processes and complex phenomena within virtual environments118. Research on the spatial distribution of phenomena, processes, and features enhances our understanding intricate interactions between humans and environmental systems119. That’s exactly what SEVL aims to do: it promotes a deeper understanding of environmental information among students by fulfilling this core mission in geography.

The VGE aims to immerse human beings and their behaviors into a virtual environment through multidimensional expression and multi-channel perception120. It achieves these goals by integrating various types of data to create a comprehensive data model that supports simulation and analysis121. SEVL simulates campus environments and designs gamified objectives, allowing students to observe the interactions between their designs and the environment through an interactive interface. This enables them to participate in this virtual space as avatars, instilling a strong sense of presence and responsibility. Students not only “experience” the environment firsthand, but also bring their knowledge and behaviors into SEVL. Through simulations of ecological relationship, they can validate design outcomes, conduct environmental analyses, and enhance their understanding of environmental information. Scholars have confirmed that having environmental information is key to developing positive environmental attitudes82,83,84. This is because environmental information influences individuals’ understanding of the importance of environmental protection and sustainability. When relevant information accumulates to a certain level, individuals’ environmental cognitive will be constructed and consequently their attitudes—may change to some extent, thereby enhancing environmental awareness14.

Therefore, SEVL can effectively elevate students’ awareness of environmental information from superficial memory to a deeper understanding and cognition, ultimately transforming it into a solidified environmental consciousness.

Furthermore, this study employs PLS-SEM to uncover two key mechanisms through which SEVL operates in environmental education. Self-efficacy indirectly enhances students’ self-efficacy by influencing learning motivation and cognitive load, plays a central mediating role in this process, thereby promoting deep environmental cognition and awareness. The findings align closely with existing theories122,123 related to virtual laboratory and gamification research. Consequently, the following two questions will be discussed: (1) How SEVL influence self-efficacy through learning motivation to enhance learning outcomes? (2) How SEVL influence self-efficacy through cognitive load to enhance learning outcomes?

In the mechanism of how SEVL boosts self-efficacy, the first point is that SEVL influences learning motivation, which in turn affects self-efficacy and ultimately leads to environmental education (VL -> LM -> SE -> EI -> EA, β = 0.040, p < 0.05, 95%CI[0.018,0.094]). Learning motivation plays a crucial role in this pathway. This finding aligns with previous research: Van Gaalen AEJ et al. suggest that gamified elements are often integrated into teaching strategies to boost student engagement and enjoyment, thereby enhancing learning motivation124. Elements such as scores and interactive components used in educational settings125, clear objectives, and immediate feedback125 can elevate learners’ expectations of success and foster a more positive attitude.

When the learning environment stimulates intrinsic curiosity and provides recognition of competence, according to motivational theory, individuals’ self-efficacy is activated, leading them to deepen their cognitive engagement126. When individuals possess strong learning motivation, they are more likely to achieve their goals, thus enhancing overall self-efficacy—especially in situations of problem discovery126. When students encounter novel tasks, they experience novelty, surprise, and freedom of action—powerful motivators—which over time bolster their confidence in handling these tasks effectively.

In SEVL, ongoing task objectives within virtual laboratory stimulate students’ exploratory interests while building their confidence—these positive emotions continuously generate feelings of novelty and assurance about solving problems. This newfound confidence activates their sense of self-efficacy and drives them to engage more deeply with environmental information65, ultimately transforming cognitive achievements into heightened environmental awareness.

The second path shows that SEVL influences self-efficacy by affecting cognitive load, which ultimately leads to environmental education (VL -> CL -> SE -> EI -> EA, β = 0.048, p < 0.05, 95%CI[0.012,0.088]). In this path, cognitive load plays a key role.

This aligns with previous research127,128, which indicates that virtual laboratory and gamified learning can reduce cognitive load. Liao et al. suggest that game-based learning integrates knowledge into gaming contexts, allowing information to be processed simultaneously through textual, three-dimensional visual and auditory methods122,123. Kolil et al. argue that this approach reduces the complexity of interaction between students and learning materials, making it easier to achieve incremental successes129 and thereby reinforcing learners’ confidence75,76. This process replaces direct experiences in the real world with vicarious influences within virtual laboratory, ultimately fostering a sense of self-efficacy95,130.

SEVL adjusts learning difficulty by breaking down tasks and providing explanatory prompts. Once students master foundational skills, they gradually tackle more complex problems, significantly reducing their cognitive load. The continuous reinforcement from successful experiences during this process fosters their belief in their own capabilities131. Therefore, students are more likely to have a deep cognition of environmental information and enhancement their environmental awareness.

Conclusion

In the context of the current global ecological and environmental crises and challenges, environmental education is a key element for achieving sustainable development11. This study developed and tested a theoretical model to explain the mechanisms of the SEVL. Based on PLS-SEM analysis, the data support the proposed pathway: SEVL stimulates learners’ motivation and optimizes their cognitive load, in turn enhances their self-efficacy. Ultimately, these effects promote a deeper understanding of environmental information and elevate environmental awareness, thereby supporting improved outcomes in environmental education. However, these advantages require systematic comparison with traditional teaching methods or other digital tools. Further validation is also necessary to more comprehensively assess the benefits of SEVL in environmental education.

From a theoretical perspective, this study identifies two mechanisms that describe how SEVL operates, highlighting the central mediating role of self-efficacy. This enriches our understanding of pathways in environmental education. this research offers an observable and verifiable cognitive tool. By creating spaces with rich geometric and physical properties117, we can map out dynamic processes and complex phenomena in virtual environments118. This helps turn abstract ecological relationships into concrete, visual experiences. Such an approach enables students to intuitively understand the interaction patterns between human activities and natural systems during the site design process, thereby enhancing the sustainability of environmental education.

At the theoretical level, the proposed framework focuses on three key psychological factors—learning motivation, cognitive load, and self-efficacy—to explain how virtual laboratory promotes deep environmental cognition and awareness. However, this framework still has limitations. Existing theoretical and empirical research indicates that other variables—such as psychological ownership, perceived importance132, immersion50, interest, embodiment, and self-regulation77,78—may also influence how learners process environmental information and internalize environmental awareness in virtual environments. The current study did not incorporate these potential mediating or moderating factors into an integrated model, thereby limiting its theoretical explanatory ability. Future research could expand upon more complex mechanistic models to examine the pathways of additional psychological and emotional variables, and further clarify the psychological mechanism structure of virtual laboratory in promoting deep cognition and environmental awareness, thereby promoting the deepening and enrichment of the theoretical system in this field.

In terms of research design, this study employed a single-group post-test design to examine the mechanistic pathways of the virtual laboratory. However, a pre-test and a control group are both absent, so it is impossible to completely rule out the difference in learners’ knowledge level before the experiment, and it is also impossible to control the possible influence of external variables during the experiment, which weakens the strength of causal inference to a certain extent. Future studies could adopt more rigorous experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials, repeated-measures designs with pre- and post-tests, or longitudinal tracking across multiple time points133. These approaches would enhance the reliability of the proposed mechanisms.

At the sample level, all participants in this study are from the same university, with relatively concentrated disciplinary backgrounds, resulting in a homogeneous sample structure. While this relatively uniform sample source helps reduce interference from varying educational backgrounds and allows clearer examination of the model’s internal mechanisms, it also limits the external validity of the findings. The sample size of 146 may also lead to instability in estimating certain path coefficients. Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals of some path coefficients are relatively wide, reflecting the impact of sample fluctuations on estimation accuracy. Therefore, caution is warranted when generalizing these results to other regions, disciplines, or educational stages. Future research could introduce larger and more diverse sample structures, incorporating multi-group analyses across institutions, regions, and educational levels. This would further test the robustness of the model across different populations, thereby improving the study’s representativeness and external validity.

Data availability

Data is provided within supplementary information files.

References

Fletcher, C. et al. Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future. PNAS Nexus. 3 (4), pgae106 (2024).

Zhang, M. & Su, C. Y. The impact of presence on the perceptions of adolescents toward immersive laboratory learning. Educ. Inform. Technol. 30 (3), 3771–3801 (2025).

Albert, J. S. et al. Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science 379 (6630), eabo5003 (2023).

Persano Adorno, D. et al. Sustainability as a cross-curricular link: creative European strategies for eco-conscious environmental education. Sustainability 17 (11), 5193 (2025).

Greenland, S. J. et al. Reducing SDG complexity and informing environmental management education via an empirical six-dimensional model of sustainable development. J. Environ. Manage. 344, 118328 (2023).

Salazar, C. et al. Environmental education and children’s pro-environmental behavior on plastic waste. Evidence from the green school certification program in Chile. Int. J. Educational Dev. 109, 103106 (2024).

UNESCO & UNEP. The Belgrade Charter: A framework for environmental education. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Environmental Education, Belgrade, Serbia. (1975).

Poore, D. International union for conservation of nature and natural resources (IUCN):* A dynamic strategy. Environ. Conserv. 4 (2), 119–120 (1977).

UNESCO & UNEP. The tbilisi declaration. in Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education. (USSR Tbilisi, 1977).

UNESCO, Tbilisi Declaration. Intergovernmental conference on environmental education. In Final Report. Paris (1978).

Uralovich, K. S. et al. A primary factor in sustainable development and environmental sustainability is environmental education. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 21 (4), 965–975 (2023).

Hsieh, H. S. Applying a self-activation change approach to modify university students’ environmental awareness and behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 1–19 (2025).

Nacaroğlu, O. & Göktaş, O. The effect of technology supported guided inquiry environmental education on preservice science, teachers’ attitudes towards sustainable environment, environmental education self-efficacy and digital literacy. J. Sci. Edu. Technol. 34 (2), 298–313 (2025).

Luo, L. et al. How does environmental education affect college students’ waste sorting behavior: A heterogeneity analysis based on educational background. J. Environ. Manage. 389, 126064 (2025).

Rūtelionė, A., Bhutto, M. Y. & Miceikienė, A. Green university initiatives and environmental self-identity: Waste sorting in baltic higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. (2025).

Kurokawa, H. et al. Improvement impact of nudges incorporated in environmental education on students’ environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. J. Environ. Manage. 325, 116612 (2023).

Aikowe, L. D. & Mazancová, J. Plastic waste sorting intentions among university students. Sustainability 13 (14), 7526 (2021).

Espinoza, I. I. B. et al. Environmental knowledge to create environmental attitudes generation toward solar energy purchase. Sustainable Futures. 9, 100558 (2025).

Srisathan, W. A. et al. The impact of citizen science on environmental attitudes, environmental knowledge, environmental awareness to pro-environmental citizenship behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 17 (1), 360–378 (2024).

Carrión-Bósquez, N. G. et al. The mediating role of attitude and environmental awareness in the influence of green advertising and eco-labels on green purchasing behaviors. Span. J. Marketing-ESIC. 29 (3), 330–350 (2025).

Xu, J. & Jiang, A. Effects of nature contact on children’s willingness to conserve animals under rapid urbanization. Global Ecol. Conserv. 38, e02278 (2022).

Acharibasam, J. B. & McVittie, J. Connecting children to nature through the integration of Indigenous ecological knowledge into early childhood environmental education. Australian J. Environ. Educ. 39 (3), 349–361 (2023).

Sherry, C. Learning from the dirt: Initiating university food gardens as a cross-disciplinary tertiary teaching tool. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 25 (2), 199–217 (2022).

Sunari, R. & Nurhayati, S. Community environmental education through a local knowledge-based learning program on plastic waste management. J. Educ. 5 (4), 13093–13099 (2023).

Earle, A. G., Leyva-de la, D. I. & Hiz The wicked problem of teaching about wicked problems: design thinking and emerging technologies in sustainability education. Manage. Learn. 52 (5), 581–603 (2021).

Gebrekidan, T. K. Environmental education in ethiopia: History, mainstreaming in curriculum, governmental structure, and its effectiveness: A systematic review. Heliyon 10(9) (2024).

Barus, I. R. G. & Simanjuntak, M. B. Integrating environmental education into maritime English curriculum for vocational learners: Challenges and opportunities. In BIO Web of Conferences. (EDP Sciences, 2023).

Eneji, C. & Kori, C. Products evaluation of environmental education curriculum/program implementation in the University of Calabar, Nigeria. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Res. 22 (4), 377–413 (2023).

Damoah, B., Khalo, X. & Adu, E. South African integrated environmental education curriculum trajectory. Int. J. Educational Res. 125, 102352 (2024).

Jarmon, L. et al. Virtual world teaching, experiential learning, and assessment: an interdisciplinary communication course in second life. Comput. Educ. 53 (1), 169–182 (2009).

Güven, G., Orhan, S., Özen & Şarlakkaya, K. Virtual reality applications integrated into the 5E learning model in environmental topics in science education. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 1–25 (2025).

Nouri, I., Zorgati, H. & Bouzaabia, R. The impact of immersive 360° video on environmental awareness and attitude toward climate change: The moderating role of cybersickness. J. Social Mark. 15 (2/3), 175–194 (2025).

Yu, W. & Jin, X. Does environmental information disclosure promote the awakening of public environmental awareness? Insights from Baidu keyword analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 375, 134072 (2022).

Jiang, N. et al. Will information interventions affect public preferences and willingness to pay for air quality improvement? An empirical study based on deliberative choice experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 868, 161436 (2023).

Burgos-Espinoza, I. I. et al. Effect of environmental knowledge on pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: A comparative analysis between engineering students and professionals in Ciudad Juárez (Mexico). J. Environ. Stud. Sci.. 1–15 (2024).

Chen, C. L. & Tsai, C. H. Marine environmental awareness among university students in Taiwan: A potential signal for sustainability of the oceans. Environ. Educ. Res. 22 (7), 958–977 (2016).

Dopelt, K., Radon, P. & Davidovitch, N. Environmental effects of the livestock industry: The relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and behavior among students in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16 (8), 1359 (2019).

Wiliam, H. Breadth and depth of knowledge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 31 (10), 443A–443A (1997).

Lü, G. et al. Data environment construction for virtual geographic environment. Environ. Earth Sci. 74 (10), 7003–7013 (2015).

Chen, M. et al. Developing dynamic virtual geographic environments (VGEs) for geographic research. Environ. Earth Sci. 74 (10), 6975–6980 (2015).

Guo, X. M. et al. Historical architecture pedagogy meets virtual technologies: A comparative case study. Educ. Inform. Technol. 29 (12), 14835–14874 (2024).

Sjöblom, P., Eklund, G. & Fagerlund, P. Student teachers’ views on outdoor education as a teaching method – Two cases from Finland and Norway. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 23 (3), 286–300 (2023).

Shambare, B. & Simuja, C. A critical review of teaching with virtual lab: A panacea to challenges of conducting practical experiments in science subjects beyond the COVID-19 pandemic in rural schools in South Africa. J. Educational Technol. Syst. 50 (3), 393–408 (2022).

Thees, M. et al. Effects of augmented reality on learning and cognitive load in university physics laboratory courses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 108, 106316 (2020).

Frederiksen, J. G. et al. Cognitive load and performance in immersive virtual reality versus conventional virtual reality simulation training of laparoscopic surgery: A randomized trial. Surg. Endosc. 34, 1244–1252 (2020).

Altmeyer, K. et al. The use of augmented reality to foster conceptual knowledge acquisition in STEM laboratory courses—Theoretical background and empirical results. Br. J. Edu. Technol. 51 (3), 611–628 (2020).

Fang, Y., Li, Y. & Fan, L. Enhanced education on geology by 3D interactive virtual geological scenes. Computers Education: X Real. 6, 100094 (2025).

Hamdan, A. et al. Geo-Virtual reality (GVR): The creative materials to construct spatial thinking skills using virtual learning based metaverse technology. Think. Skills Creativ. 54, 101664 (2024).

Yin, W. et al. Harnessing game engines and digital twins: Advancing flood education, data visualization, and interactive monitoring for enhanced hydrological understanding. Water 16 (17), 2528 (2024).

Van Horen, F. et al. Observing the Earth from space: Does a virtual reality overview effect experience increase pro-environmental behaviour? Plos One. 19 (5), e0299883 (2024).

Attanasi, G. et al. Raising environmental awareness with augmented reality. Ecol. Econ. 233, 108563 (2025).

Safitri, D. et al. Ecolabel with augmented reality on the website to enhance student environmental awareness. Int. J. Ecol. 2022 (1), 8169849 (2022).

Radu, I. Augmented reality in education: A meta-review and cross-media analysis. Personal. Uniquit. Comput. 18 (6), 1533–1543 (2014).

Makransky, G., Terkildsen, T. S. & Mayer, R. E. Adding immersive virtual reality to a science lab simulation causes more presence but less learning. Learn. Instruction. 60, 225–236 (2019).

Ali, N., Ullah, S. & Khan, D. Minimization of students’ cognitive load in a virtual chemistry laboratory via contents optimization and arrow-textual aids. Educ. Inform. Technol. 27 (6), 7629–7652 (2022).

Ali, N. et al. The effect of adaptive aids on different levels of students’ performance in a virtual reality chemistry laboratory. Educ. Inform. Technol. 29 (3), 3113–3132 (2024).

Diwakar, S. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among students for laboratory courses-assessing the impact of virtual laboratories. Comput. Educ. 198, 104758 (2023).

Sari, U. et al. The effects of virtual and computer based real laboratory applications on the attitude, motivation and graphic interpretation skills of university students. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 27(1) (2019).

Cho, Y. & Park, K. S. Designing immersive virtual reality simulation for environmental science education. Electronics 12 (2), 315 (2023).

Garris, R., Ahlers, R. & Driskell, J. E. Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simul. Gaming. 33 (4), 441–467 (2002).

Ishak, S. A., Din, R. & Hasran, U. A. Defining digital game-based learning for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: A new perspective on design and developmental research. J. Med. Internet Res. 23(2) (2021).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84 (2), 191 (1977).

Birt, J., Moore, E. & Cowling, M. Improving paramedic distance education through mobile mixed reality simulation. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 33(6) (2017).

Andalib, S. Y. et al. Enhancing landscape architecture construction learning with extended reality (XR): comparing interactive virtual reality (VR) with traditional learning methods. Educ. Sci. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080992 (2025).

Britner, S. L. & Pajares, F. Sources of science self-efficacy beliefs of middle school students. J. Res. Sci. Teaching: Official J. Natl. Association Res. Sci. Teach. 43 (5), 485–499 (2006).

Pajares, F. & Valiante, G. Influence of self-efficacy on elementary students’ writing. J. Educational Res. 90 (6), 353–360 (1997).

Malone, T. W. & Lepper, M. R. Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. In Aptitude, Learning, and Instruction (ed. I.R.E.S.M.J, F.). 223–253. ( Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987).

Rigby, S. & Ryan, R. M. Glued to games: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound. In Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw Us in and Hold Us Spellbound.186-xiii (2011).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 (1), 54–67 (2000).

Hardré, P. L. & Sullivan, D. W. Student differences and environment perceptions: how they contribute to student motivation in rural high schools. Learn. Individual Differences. 18 (4), 471–485 (2008).

Linnenbrink, E. A. & Pintrich, P. R. Motivation as an enabler for academic success. School Psychol. Rev. 31 (3), 313–327 (2002).

Kamberi, M. The types of intrinsic motivation as predictors of academic achievement: The mediating role of deep learning strategy. Cogent Educ. 12 (1), 2482482 (2025).

Hsia, L. H., Huang, I. & Hwang, G. J. Effects of different online peer-feedback approaches on students’ performance skills, motivation and self-efficacy in a dance course. Comput. Educ. 96, 55–71 (2016).

Liao, C. W., Chen, C. H. & Shih, S. J. The interactivity of video and collaboration for learning achievement, intrinsic motivation, cognitive load, and behavior patterns in a digital game-based learning environment. Comput. Educ. 133, 43–55 (2019).

Bonghawan, R. G. G. & Macalisang, D. E. Teachers’ learning reinforcement: Effects on students’ motivation, self efficacy and academic performance. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. (IJSRM) 12(02) (2024).

Koestner, R. et al. Setting limits on children’s behavior: The differential effects of controlling vs. informational styles on intrinsic motivation and creativity. J. Pers. 52 (3), 233–248 (1984).

Makransky, G. & Petersen, G. B. The cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educational Psychol. Rev. 33 (3), 937–958 (2021).

Makransky, G. & Lilleholt, L. A structural equation modeling investigation of the emotional value of immersive virtual reality in education. Education Tech. Research Dev. 66 (5), 1141–1164 (2018).

Wu, H. et al. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med. Educ. Online. 25 (1), 1742964 (2020).

Bishara, S. Linking cognitive load, mindfulness, and self-efficacy in college students with and without learning disabilities. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 37 (3), 494–510 (2022).

Balalle, H. Exploring student engagement in technology-based education in relation to gamification, online/distance learning, and other factors: A systematic literature review. Social Sci. Humanit. Open. 9, 100870 (2024).

Burgos-Espinoza, I. I. et al. Effect of environmental knowledge on pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: A comparative analysis between engineering students and professionals in Ciudad Juárez (Mexico). J. Environ. Stud. Sci. (2024).

Shah, S. S. & Asghar, Z. Individual attitudes towards environmentally friendly choices: A comprehensive analysis of the role of legal rules, religion, and confidence in government. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 14 (4), 629–651 (2024).

Tamar, M. et al. Predicting pro-environmental behaviours: the role of environmental values, attitudes and knowledge. Manage. Environ. Quality: Int. J. 32 (2), 328–343 (2021).

Rupke, N. A. Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

McHarg, I. L. Design with Nature (1969).

Lyle, J. T. Can floating seeds make deep forms? Landsc. J. 10 (1), 37–47 (1991).

Steiner, F. R. The Living Landscape: An Ecological Approach to Landscape Planning (Island, 2012).

Joshi, A. et al. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 7 (4), 396 (2015).

Davis, F., Davis, F., Usefulness, P. & Perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13, 319 (1989).

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Q. 19 (4), 561–570 (1995).

Lee, D., Moon, J. & Kim, Y. The effect of simplicity and perceived control on perceived ease of use. (2007).

Pintrich, P. et al. A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Ann. Arbor Mich. 48109, 1259 (1991).

Credé, M. & Phillips, L. A. A meta-analytic review of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2011, 337–346 (2011) .

Locke, E. A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Pers. Psychol. 50 (3), 801 (1997).

Pintrich, P. R. & Schunk, D. H. Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (2002).

Leppink, J. et al. Development of an instrument for measuring different types of cognitive load. Behav. Res. Methods. 45 (4), 1058–1072 (2013).

Tukey, J. W. Exploratory Data Analysis. Vol. 2 (Springer, 1977).

Frigge, M., Hoaglin, D. C. & Iglewicz, B. Some implementations of the boxplot. Am. Stat. 43 (1), 50–54 (1989).

Williamson, D. F., Parker, R. A. & Kendrick, J. S. The box plot: A simple visual method to interpret data. Ann. Intern. Med. 110 (11), 916–921 (1989).

Latif, K. F. et al. Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on project success: Mediating role of knowledge management processes. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 41 (2), 237–256 (2020).

Hair, J. et al. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (Sage Publications, Inc., 2017).

Hair, J. et al. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31 (2018).

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19 (2), 139–152 (2014).

Hair, J. F. et al. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45 (5), 616–632 (2017).

Nitzl, C. The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. J. Acc. Literature. 37, 19–35 (2016).

Kock, N. & Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inform. Syst. J. 28 (1), 227–261 (2018).

Hair, J. J. F. et al. Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: part I–method. Eur. Bus. Rev. 28 (1), 63–76 (2016).

Asadi, S. et al. Customers perspectives on adoption of cloud computing in banking sector. Inf. Technol. Manage. 18, 305–330 (2017).

Hair, J. F. et al. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 40, 414–433 (2012).

Asadi, S. et al. Investigating factors influencing decision-makers’ intention to adopt green IT in Malaysian manufacturing industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 148, 36–54 (2019).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 (1), 39–50 (1981).

Lin, H. M. et al. A review of using partial least square structural equation modeling in e-learning research. Br. J. Edu. Technol. 51 (4), 1354–1372 (2020).

Streukens, S. & Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 34 (6), 618–632 (2016).

Lever, J., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. Points of significance: Principal component analysis. Nat. Methods. 14 (7), 641–643 (2017).

Lin, H. et al. Virtual geographic environments (VGEs): A new generation of geographic analysis tool. Earth Sci. Rev. 126, 74–84 (2013).

Chen, M. & Lin, H. Virtual geographic environments (VGEs): Originating from or beyond virtual reality (VR)? Int. J. Digit. Earth. 11 (4), 329–333 (2018).

Lü, G. et al. Geographic scenario: A possible foundation for further development of virtual geographic environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 11 (4), 356–368 (2018).

Lin, H., Chen, M. & Lu, G. Virtual geographic environment: A workspace for computer-aided geographic experiments. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 103 (3), 465–482 (2013).

Rauschert, I. et al. Designing a human-centered, multimodal GIS interface to support emergency management. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Symposium on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. 119–124 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2002).

Francos, A. et al. Sensitivity analysis of distributed environmental simulation models: Understanding the model behaviour in hydrological studies at the catchment scale. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 79 (2), 205–218 (2003).

Chen, H. L. & Wu, C. T. A digital role-playing game for learning: Effects on critical thinking and motivation. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31 (5), 3018–3030 (2023).

Chen, C. C. & Huang, P. H. The effects of STEAM-based mobile learning on learning achievement and cognitive load. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31 (1), 100–116 (2023).

van Gaalen, A. E. et al. Gamification of health professions education: A systematic review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 26 (2), 683–711 (2021).

Banfield, J. & Wilkerson, B. Increasing student intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy through gamification pedagogy. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 7 (4), 291–298 (2014).

Stone, D. N., Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Beyond talk: Creating autonomous motivation through self-determination theory. J. Gen. Manage. 34 (3), 75–91 (2009).

Chang, C. C. et al. Effects of digital game-based learning on achievement, flow and overall cognitive load. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 34(4) (2018).

Chang, C. C. et al. Is game-based learning better in flow experience and various types of cognitive load than non-game-based learning? Perspective from multimedia and media richness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 71, 218–227 (2017).

Kolil, V. K., Muthupalani, S. & Achuthan, K. Virtual experimental platforms in chemistry laboratory education and its impact on experimental self-efficacy. Int. J. Educational Technol. High. Educ. 17 (1), 30 (2020).

Zimmerman, B. J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 (1), 82–91 (2000).

Bandura, A. & Schunk, D. H. Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 41 (3), 586 (1981).

Zhang, F. Enhancing ESG learning outcomes through gamification: An experimental study. Plos One. 19 (5), e0303259 (2024).

Lee, J., Chen, C. & Basu, A. From novelty to knowledge: A longitudinal investigation of the novelty effect on learning outcomes in virtual reality. In IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the comments and criticisms of the journal’s anonymous reviewers and our colleagues.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of education of Humanities and Social Science project, grant number 24YJA760026. This study was funded by Funding by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou, grant number 2023A04J1561.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and P.C.; methodology, P.C.; software, Y.J.L. and P.C. and L.H.X.; validation, W.G. and P.C.; formal analysis, W.G. and P.C.; investigation, S.J.H.; resources, L.H.X. and S.J.H.; data curation, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, W.G. and P.C.; visualization, P.C.; supervision, S.J.H. and L.H.X.; project administration, W.G. and L.H.X. and S.J.H.; funding acquisition, W.G. and S.J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Approval is obtained from the Institutional Review Board of College of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University. Participants are recruited based on the principles of voluntary and informed consent, and the rights and privacy of participants are protected. There is no conflict of interest as well as violation of moral ethics and legal prohibitions in the content of the study. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and Belmont.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, W., Chen, P., Hu, S. et al. Research on the mechanism of improving environmental information cognition and environmental awareness in site ecological virtual laboratory. Sci Rep 16, 5289 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35279-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35279-x