Abstract

Metabolic acidosis (MA) is common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is associated with adverse effects. Despite guidelines recommending treatment, reports from Western countries have suggested that MA is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. However, the situation in Asia remains unclear. This study aims to assess the serum bicarbonate measurement rate and the prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment rates of MA in Asian CKD patients using the Japan chronic kidney disease database (J-CKD-DB-Ex). Patients included were aged 18 years or older and had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) between 15 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m². We evaluated the rate of serum bicarbonate measurement in each year from 2014 to 2021. Among patients with at least one serum bicarbonate measurement during the study period, we assessed the prevalence of MA (serum bicarbonate < 22 mEq/L), and the diagnosis and treatment rates, based on ICD-10 codes and sodium bicarbonate prescriptions. The annual measurement rate of serum bicarbonate was consistently less than 10%. The prevalence of MA among patients with at least one serum bicarbonate measurement was 44.2%. Diagnosis and treatment rates in patients with MA were 8.6 and 7.5%, respectively. This study demonstrated that MA may be inadequately assessed and treated in Japanese patients with CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic acidosis (MA) is common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and can have significant adverse effects, including altered skeletal metabolism, insulin resistance, and protein-energy wasting1,2. In addition, MA has been potentially associated with CKD progression and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality3,4,5,6,7. In reports from Western countries, the prevalence of MA, defined as a serum bicarbonate level below 22 mEq/L, increases with declining kidney function, ranging from 1.3% to 7% in stage 2 CKD, 2.3% to 13% in stage 3 CKD, and 19 to 37% in stage 4 CKD8,9. In those studies, the prevalence of MA has been investigated using serum bicarbonate or total CO₂ levels. However, measurement rates of these parameters have not been systematically evaluated and it remains unclear whether these parameters are routinely measured in clinical practice. It is essential to first assess the measurement rate itself, as it directly affects the diagnosis and management of MA.

In CKD patients with MA, alkaline therapy, including sodium bicarbonate and sodium citrate, has been reported to slow the decline in kidney function and reduce the risk of end-stage kidney disease10,11. A meta-analysis reported the efficacy of dietary interventions that reduce dietary acid load may be as effective as alkalizing agents such as sodium bicarbonate in preventing renal functional decline12. According to the National Kidney Foundation–Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-KDOQI), alkali therapy is recommended for CKD patients with serum bicarbonate levels below 22 mEq/L13. Similarly, the Japanese CKD guidelines published in 2023 recommend the initiation of sodium bicarbonate treatment for serum bicarbonate levels below 22 mEq/L14. In addition, the updated Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 guidelines suggest that it is desirable to avoid a serum bicarbonate level of < 18 mmol/L in adults, recommending pharmacological treatment with or without dietary modifications15. Despite these recommendations, Western studies analyzing clinical data diagnosed MA in only 20%-45% of CKD patients with decreased bicarbonate16. In addition, only 8%-18% of these patients received sodium bicarbonate treatment16. In other studies, the proportion of patients receiving alkali therapy such as sodium bicarbonate was 2.7% in those with serum bicarbonate of ≤ 22 mEq/L7, and 2.0% in those with ≤ 24 mEq/L17. These studies suggest that the diagnosis and treatment of MA in patients with CKD may be inadequate, despite it being a risk factor for renal functional decline.

However, the details of this issue in Asian CKD patients remain unclear. Given that the dietary acid load in Japan may be lower than that in a typical Western diet18, it is possible that the prevalence of MA may also vary. Moreover, alkali therapy may not be widely implemented in the management of CKD in Asia. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the current status of MA management.

We conducted this study to assess the serum bicarbonate measurement rate and the prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment rates of MA in CKD patients in Japan using the Japan Chronic Kidney Disease Database (J-CKD-DB), a nationwide electronic medical record database.

Results

Annual assessment of metabolic acidosis in CKD

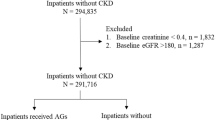

The average annual number of patients for the period 2014–2021 was 58,010 (range: 47,489 − 67,256). Table 1 shows the annual characteristics of the study population. Mean age ranged from 70 to 71 years across the study period. The proportion of male patients ranged from 52.7% to 54.8%, and the mean eGFR ranged from 45.7 to 46.8 mL/min/1.73 m2. In this population, serum bicarbonate was measured at least once in 7.91%–9.01% of patients each year. Among patients with serum bicarbonate measurements, the mean serum bicarbonate concentration ranged from 24.49 to 25.69 mEq/L. The prevalence of MA ranged from 2.61% to 3.11%, the rate of MA diagnosis ranged from 0.17% to 0.27%, and the rate of MA treatment, indicated by sodium bicarbonate prescription, ranged from 0.10% to 0.16%. These estimates represent the proportion among the entire annual population, regardless of whether serum bicarbonate was measured. Table 2 shows the rate of serum bicarbonate measurement, the prevalence of MA, and the rates of MA diagnosis and treatment according to CKD stage, which appeared to increase with advancing CKD stage.

Analysis based on serum bicarbonate measurements from 2014 to 2021

For analyses related to MA, patients were classified according to serum bicarbonate measurement status and bicarbonate level. Throughout the period from 2014 to 2021, 22,309 patients had at least one serum bicarbonate measurement, whereas 157,135 patients had no documented serum bicarbonate level. Figure 1A shows the proportion of patients with MA in the group with at least one measurement. The overall prevalence of MA in this group was 44.2%. Stratified by CKD stage, the prevalence rates in patients with G3a, G3b, and G4 were 31.8, 46.4, and 65.8%, respectively. Figure 1B shows the diagnosis and treatment rates among patients in whom MA was identified. Among those patients, 8.6% were diagnosed with MA and 7.5% were treated. When stratified by CKD stage, the diagnosis rate in patients with G3a, G3b, and G4 was 4.8, 6.9, and 13.7%, respectively. Thus, the diagnosis rate was higher in patients with more advanced CKD. Similarly, the treatment rate was 3.6, 5.2, and 13.4% in patients with G3a, G3b, and G4, respectively.

The overall distribution of the lowest recorded serum bicarbonate values is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 among patients with at least one serum bicarbonate measurement. Figure 2 shows violin plots illustrating the distribution of the lowest recorded serum bicarbonate values in these treated and untreated patients, overall and stratified by CKD stage. The average serum bicarbonate value, based on the lowest recorded measurement during the study, was 18.81 mEq/L in the treated group and 22.10 mEq/L in the untreated group.

Table 3 shows patient characteristics categorized by serum bicarbonate measurement status and serum bicarbonate levels (< 22 or ≥ 22 mEq/L). From 2014 to 2021, there were 157,135 patients without a documented serum bicarbonate level. The mean age of these patients was 71 ± 12.4 years, and 52.0% were male. Meanwhile, there were 22,309 patients in whom serum bicarbonate was measured during the study period. The mean age of these patients was 73 ± 13.3 years and 57.3% were male. Compared with the non-measured group, the measured group tended to be older and had lower eGFR values, higher levels of proteinuria, and higher serum potassium. They also had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, and more frequent use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, diuretics, and statin. All these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001). This group of patients was further stratified by serum bicarbonate level. Patients with bicarbonate levels below 22 mEq/L (n = 9,702) had a mean age of 73 ± 13.8 years and 61.3% were male. In contrast, patients with bicarbonate levels of 22 mEq/L or higher (n = 12,607) had a mean age of 74 ± 13.0 years and 54.3% were male.

Discussion

This study investigated the status of the diagnosis and treatment of MA in patients with CKD using J-CKD-DB-Ex, a nationwide electronic medical record database in Japan. To our knowledge, this is the first report to systematically investigate the measurement rate of serum bicarbonate levels in patients with CKD. The annual measurement rate of serum bicarbonate levels in patients with CKD stages 3a to 4 was consistently below 10% across all years examined, suggesting that MA itself may be underassessed in this population. Furthermore, although interventions for MA in CKD patients are recommended to potentially suppress the deterioration of kidney function, our analysis showed that even among cases with serum bicarbonate levels below 22 mEq/L, the diagnosis and treatment rates were only 8.6% and 7.5%, respectively. These findings suggest that treatment for MA may not be actively implemented in CKD patients.

To analyze acid–base disorders, serum total CO2 is commonly measured as a surrogate for HCO3− in Western countries. Serum total CO₂ is strongly correlated with HCO₃⁻ concentration in pre-dialysis CKD patients19. In many medical facilities in Japan, serum HCO3− levels are measured using blood gas analyzers20. However, this study suggests that serum bicarbonate levels are not frequently measured in CKD care in Japan, with a clinical trend toward higher measurement rates as the CKD stage progresses, ranging from only 5%-6% in stage 3a to 9%-11% in stage 3b, and around 20%–22% in stage 4. The stability of these annual measurement rates over the study period may be attributable to the absence of significant changes in guideline recommendations for metabolic acidosis during the study period. Compared with the group without serum bicarbonate measurements, the measured group tended to have higher levels of proteinuria, lower serum potassium levels, higher prevalence of comorbidities, and were more frequently treated with various medications. These patterns suggest that bicarbonate measurements are more likely to be performed in patients with greater clinical complexity and a perceived higher risk of acid–base disturbances, rather than in the overall CKD patient population.

In a retrospective cohort study involving 1,058 patients with CKD, 59% of cases with venous bicarbonate levels of ≤ 21.5 mEq/L had acidemia (pH < 7.32), suggesting that low bicarbonate levels do not necessarily indicate acidemia or MA21. Furthermore, the association between hypobicarbonatemia and kidney failure with replacement therapy (KFRT) was observed in only patients with acidemia (pH < 7.32), while no significant association was found among those with acidemia (pH ≥ 7.32)21. MA is categorized into hyperchloremic MA with a normal anion gap and high anion gap MA, which occurs in the later stages of CKD22. In a study involving 1,168 patients with CKD stages 3b-5, a high anion gap was associated with an increased risk of progression to KFRT and higher mortality, compared to hyperchloremic acidosis23. These findings indicate the need for further investigation of MA, with particular attention to serum bicarbonate, pH, and anion gap. However, because blood pH and anion gap were not available in this registry, low serum bicarbonate levels alone cannot confirm that metabolic acidosis was correctly assessed in our study. Nevertheless, the measurement rates observed in this study may limit the feasibility of such comprehensive assessments, highlighting an important issue.

Our study suggested a progressive increase in the prevalence of MA with advancing CKD stages, reaching 31.8%, 46.4%, and 65.8% in stages 3a, 3b, and 4, respectively. These findings are consistent with trends reported in Western countries, where the prevalence of MA is estimated to be 1.3%-7% in CKD stage 2, 2.3%-13% in stage 3, and 19%-37% in stage 48,9. A previous study in Asia similarly reported that, in a cohort with a mean eGFR of 25.9 ± 14.0 mL/min/1.73 m², 25.1% of patients had serum bicarbonate concentrations below 21.5 mEq/L21. The prevalence observed in our study was higher than that reported in both Western and Asian studies. This discrepancy may be partly explained by methodological differences, such as the use of the lowest recorded serum bicarbonate levels and a low measurement rate, which may have biased the data toward cases with suspected MA. Despite these limitations, our results support the importance of recognizing and managing MA, particularly in patients in the advanced stages of CKD, where the prevalence of MA is significantly increased.

A large retrospective cohort study from North America found that among patients with CKD, only 20%-45% of those with low serum bicarbonate levels were diagnosed with MA16. In addition, only 8%-18% of these patients were treated with sodium bicarbonate16. In the present study, the diagnosis and treatment rates were 8.6% and 7.5%, respectively, suggesting that the management of MA may be insufficient in Asia, consistent with findings reported in the North American cohort. Even among patients whose bicarbonate levels were measured and found to be below 22 mEq/L, many remained undiagnosed and untreated. Moreover, serum bicarbonate levels were not routinely measured in many patients, suggesting that they did not have the opportunity to be diagnosed or treated. A previous study suggested that the low rates of diagnosis and treatment may be attributable to insufficient awareness of MA as a disease-modifying complication of CKD among primary care physicians and nephrologists16. Vincent-Johnson et al. reviewed challenges in MA treatment and noted that the relatively low rates of treatment may reflect the lack of strong evidence supporting alkali therapy, concerns about potential risks such as worsening hypertension and edema due to sodium loading, and the unclear relative importance of treating chronic MA amid other priorities in CKD, likely limiting its implementation24. Other than the aforementioned study and our findings, there have been no reports on the rate of MA diagnosis. While several studies have documented its treatment, they also found that the rates of treatment were low. In a study involving 1,058 CKD patients, the treatment rate in the group with serum bicarbonate levels below 21.5 mEq/L was 24.4%21. Although serum bicarbonate levels were not included in a study of CKD patients in Japan, sodium bicarbonate treatment rates were reported to be 1.0% for G3a, 3.7% for G3b, 11.0% for G4, and 25.8% for G525.

MA has been reported to be a risk factor for the progression of kidney disease7,26 and increased mortality5,6,27 in CKD patients with serum bicarbonate levels below 22 mmol/L. A meta-analysis including patients with stage 3–5 CKD and MA (< 22 mEq/L) or low normal serum bicarbonate (22–24 mEq/L) suggested that oral alkali supplementation or a reduction in dietary acid intake may slow the rate of kidney function decline and potentially reduce the risk of end-stage kidney disease in patients with CKD and MA21. The 2024 KDIGO guidelines recommend considering pharmacological treatment for adults with bicarbonate levels greater than 18 mmol/L, with or without dietary interventions15. In our study, the average serum bicarbonate level in the treated group was 18.81 mEq/L. Since this value was based on the lowest recorded measurement during the study period, it likely reflects a value relatively close to the time of treatment initiation. Notably, this level was very close to the KDIGO-recommended threshold for considering pharmacological treatment. However, further evidence and discussion is needed regarding the threshold for intervention, therapeutic goals, and the choice between pharmacological or dietary therapy for MA.

Recently, evolving evidence suggests that acid accumulation begins early in CKD, even when it is not enough to manifest as MA at normal bicarbonate levels, and also appears to cause kidney injury and the progression of CKD28. Furthermore, diets with higher dietary acid load, typical of modern society, are suggested to contribute to early acid retention in patients with CKD, indicating the potential need to consider dietary interventions even before overt MA manifests29. The clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in the NKF KDOQI recommend reducing dietary acid load in patients with CKD by increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables, which may help slow the decline of residual kidney function30. A meta-analysis showed that dietary interventions aimed at reducing the acid load and/or adding base may have beneficial effects on kidney function and improving serum bicarbonate levels, with no adverse effects on serum potassium or nutritional status31. In this study, no notable difference was observed in the rates of MA diagnosis and sodium bicarbonate treatment, suggesting that dietary interventions may have been limited. Early consideration of dietary therapy, in addition to pharmacologic approaches, may be beneficial in the management of MA in CKD patients.

This study has some limitations. First, it relied on single-point measurements and the lowest eGFR values and serum bicarbonate levels, as in previous studies32,33, which may not completely reflect the variability or steady-state conditions of kidney function and acid–base balance over time and may have overestimated the prevalence of MA. Although this cohort consisted of patients with CKD, the possibility that some patients may have had AKI cannot be entirely excluded. Second, although the J-CKD-DB includes data from multiple institutions, all of them are university hospitals in Japan. Therefore, patterns of care in this cohort may differ from those in community hospitals, smaller regional facilities, or primary care clinics, and the rate of bicarbonate measurement and the rates of diagnosis and treatment of metabolic acidosis reported here are likely higher than in non-university settings. These differences may limit the generalizability of our findings to other countries or community-based settings. Third, we were unable to obtain information on socioeconomic status, the type of outpatient clinic (general vs. specialist), or the specialty of the treating physician (e.g., endocrinologist vs. nephrologist). These factors may influence serum bicarbonate measurement and broader aspects of clinical practice but could not be analyzed in this study. Fourth, although serum bicarbonate levels were probably mostly from venous blood, we could not distinguish between arterial and venous blood samples in the dataset. As previous meta-analyses have shown a correlation between venous and arterial bicarbonate concentrations34, we believe that the potential mixing of measurement methods likely had little impact on the results. Fifth, MA was assessed by serum bicarbonate levels alone, without consideration of pH or anion gap, which may be important markers of acid–base balance. Moreover, the treatment of MA was assessed solely based on the prescription of sodium bicarbonate, because data on sodium citrate/potassium citrate and dietary interventions were not available in the database. It is possible that other alkali therapies, such as sodium citrate/potassium citrate, or dietary interventions involving increased consumption of vegetables and fruits may have been utilized but were not accounted for in the treatment rate. These factors may have resulted in misclassification of MA status and underestimation of its treatment rate. Sixth, the use of ICD-10 codes may underestimate the diagnosis rate, as MA is often undercoded in clinical practice. Finally, we did not assess the effect of medications such as diuretics or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, which can affect acid–base homeostasis.

In conclusion, this study suggests that MA may be inadequately assessed and undertreated in Japanese patients with CKD, as indicated by low rates of serum bicarbonate measurement, diagnosis, and treatment of MA, based on nationwide real-world data from Asia. These findings support the importance of improving clinical management, including serum bicarbonate measurement and diagnosis, to enhance the treatment of MA through dietary and oral alkaline therapies, which may potentially benefit patients with CKD.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This was a cross-sectional study using the J-CKD-DB-Ex, a longitudinal CKD database extended from the J-CKD-DB database (UMIN trial number, UMIN000026272), with data collected from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 202135. This nationwide registry includes clinical data from 21 university hospitals across Japan, including outpatient and inpatient records, prescriptions, diagnostic codes, and laboratory results. The J-CKD-DB-Ex inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older with proteinuria of 1 + or higher (dipstick test) or eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m². Cases meeting these criteria were extracted from the J-CKD-DB-Ex database35. For this analysis, only patients with an eGFR between 15 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m² were included, regardless of proteinuria status. Data collection is standardized using the Standardized Structured Medical Information Exchange 2 (SS-MIX2) storage format integrated with an electronic medical record system. The SS-MIX2 system was developed to enable the structured exchange of medical information, ensuring compatibility across healthcare facilities. It incorporates internationally recognized standards such as Health Level Seven (HL7) Version 2.5 (ISO 27931) for patient profile data, Hospital Standardized Order Coding (HOT) reference codes for prescriptions, Japanese Laboratory Code Version 10 (JLAC10) for laboratory test results, and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) for diagnostic codes36,37,38. Using the SS-MIX2 storage system, data were automatically transferred to the J-CKD-DB-Ex data center for analysis. All patient information was de-identified, and informed consent was obtained through an opt-out process available on each hospital’s website. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Niigata University (approval number: 2023 − 0302) and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study definition

Patients were categorized into three stages based on their eGFR values: stage 3a (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m²), stage 3b (eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m²), and stage 4 (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m²)15. eGFR was calculated using the eGFR equation for Japanese adults: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × serum creatinine value − 1.094 × age− 0.287 (× 0.739 [for women])39. MA was defined according to the 2023 Japanese CKD guidelines, which recommend sodium bicarbonate treatment for serum bicarbonate levels below 22 mEq/L14. The prevalence of MA was determined based on a serum bicarbonate concentration below 22 mEq/L or a prescription for sodium bicarbonate. The diagnosis of MA was identified by ICD-10 code E87.2, linked to Japanese insurance claims records for each patient. Treatment of MA was estimated based on the prescription of sodium bicarbonate.

Annual assessment of metabolic acidosis in CKD

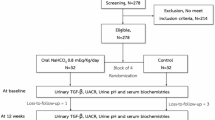

For patients in each year from 2014 to 2021, the index date was defined as the date of the eGFR measurement within the range 15–60 mL/min/1.73 m² during each year, with the lowest value used when multiple values were available for the same patient, as performed in a previous study32,33. The flowchart of patients included in this analysis is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 (A). Serum bicarbonate measurement rate was estimated from at least one measurement during each year. The annual evaluation assessed the prevalence of MA using the serum bicarbonate value closest to the index date or the presence of a sodium bicarbonate prescription, while the diagnosis and treatment were determined from at least one record in each year. These estimates were calculated for the entire annual population, including patients without serum bicarbonate measurement.

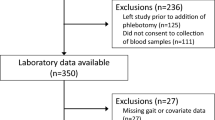

Analysis based on serum bicarbonate measurements from 2014 to 2021

For patients with at least one measurement of serum bicarbonate during the study period (2014–2021), the index date was defined as the date of the lowest recorded serum bicarbonate concentration. The flowchart of patients included in this analysis is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 (B). We evaluated the serum bicarbonate value and proportion of patients with MA among those with measurements. Additionally, among patients with MA, we assessed the MA diagnosis and treatment rates. For patients without serum bicarbonate measurements, the index date was based on the lowest recorded eGFR within the range 15–60 mL/min/1.73 m² within the study period.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient characteristics, laboratory values, and comorbidities were presented as means ± standard deviation or frequencies and percentages. To account for potential discrepancies, relevant laboratory values within ± 1 month of each patient’s index date were included, as not all laboratory measurements were available on the index date. The proportion of patients with measurement of serum bicarbonate, the prevalence of MA, and the rates of MA diagnosis and treatment were calculated by dividing the number of eligible patients meeting each criterion by the total number of eligible patients. We compared characteristics between patients with and without measured serum bicarbonate levels using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the two-sample t-test for continuous variables. Furthermore, these were analyzed, with stratification by CKD stage and serum bicarbonate level (< 22 mEq/L and ≥ 22 mEq/L groups). All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft SQL Server 2017 (ver. 14.0.2070.1; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and SAS (ver. 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Chen, W. & Abramowitz, M. K. Metabolic acidosis and the progression of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 15, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-15-55 (2014).

Kraut, J. A. & Madias, N. E. Consequences and therapy of the metabolic acidosis of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 26, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1564-4 (2011).

Tangri, N. et al. Increasing serum bicarbonate is associated with reduced risk of adverse kidney outcomes in patients with CKD and metabolic acidosis. Kidney Int. Rep. 8, 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2023.01.029 (2023).

Collister, D. et al. Metabolic acidosis and cardiovascular disease in CKD. Kidney Med. 3, 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xkme.2021.04.011 (2021). e751.

Navaneethan, S. D. et al. Serum bicarbonate and mortality in stage 3 and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 2395–2402. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.03730411 (2011).

Kovesdy, C. P., Anderson, J. E. & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Association of serum bicarbonate levels with mortality in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Nephrol. Dialysis Transplantation. 24, 1232–1237. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfn633 (2008).

Dobre, M. et al. Association of serum bicarbonate with risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD: a report from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 62, 670–678. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.017 (2013).

Raphael, K. L., Zhang, Y., Ying, J. & Greene, T. Prevalence of and risk factors for reduced serum bicarbonate in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. (Carlton). 19, 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.12315 (2014).

Eustace, J. A., Astor, B., Muntner, P. M., Ikizler, T. A. & Coresh, J. Prevalence of acidosis and inflammation and their association with low serum albumin in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 65, 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00481.x (2004).

Alva, S., Divyashree, M., Kamath, J., Prakash, P. S. & Prakash, K. S. A study on effect of bicarbonate supplementation on the progression of chronic kidney disease. Indian J. Nephrol. 30, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijn.IJN_93_19 (2020).

Phisitkul, S. et al. Amelioration of metabolic acidosis in patients with low GFR reduced kidney endothelin production and kidney injury, and better preserved GFR. Kidney Int. 77, 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.519 (2010).

Navaneethan, S. D., Shao, J., Buysse, J. & Bushinsky, D. A. Effects of treatment of metabolic acidosis in CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14 (2019).

K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 42, S1–201 (2003).

Essential points from evidence-based clinical practice guideline for chronic kidney disease 2023. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 28, 473–495 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-024-02497-4 (2024).

, K. D. I. G. O. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 105, S117-s314 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018 (2024).

Whitlock, R. H. et al. Metabolic acidosis is undertreated and underdiagnosed: a retrospective cohort study. Nephrol. Dialysis Transplantat. 38, 1477–1486. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfac299 (2023).

Dobre, M. et al. Serum bicarbonate concentration and cognitive function in hypertensive adults. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 596–603. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.07050717 (2018).

Toba, K. et al. Higher estimated net endogenous acid production with lower intake of fruits and vegetables based on a dietary survey is associated with the progression of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1591-8 (2019).

Hirai, K. et al. Approximation of bicarbonate concentration using serum total carbon dioxide concentration in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 38, 326–335. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.19.027 (2019).

Hirai, K. et al. Relationship between serum total carbon dioxide concentration and bicarbonate concentration in patients undergoing Hemodialysis. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 39, 441–450. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.19.126 (2020).

Kajimoto, S., Sakaguchi, Y., Asahina, Y., Kaimori, J. Y. & Isaka, Y. Modulation of the association of hypobicarbonatemia and incident kidney failure with replacement therapy by venous pH: A cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 77, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.06.019 (2021).

Zijlstra, H. W. & Stegeman, C. A. The elevation of the anion gap in steady state chronic kidney disease May be less prominent than generally accepted. Clin. Kidney J. 16, 1684–1690. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfad100 (2023).

Asahina, Y. et al. Association of Time-Updated anion gap with risk of kidney failure in advanced CKD: A cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 79, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.05.022 (2022).

Vincent-Johnson, A. & Scialla, J. J. Importance of metabolic acidosis as a health risk in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 29, 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2022.05.002 (2022).

Inaguma, D. et al. Risk factors for CKD progression in Japanese patients: findings from the chronic kidney disease Japan cohort (CKD-JAC) study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 21, 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-016-1309-1 (2017).

Shah, S. N., Abramowitz, M., Hostetter, T. H. & Melamed, M. L. Serum bicarbonate levels and the progression of kidney disease: A cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 54, 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.02.014 (2009).

Raphael, K. L. et al. Serum bicarbonate and mortality in adults in NHANES III. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 28, 1207–1213. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs609 (2013).

Wesson, D. E. The continuum of acid stress. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16 (2021).

Goraya, N. & Wesson, D. E. Pathophysiology of Diet-Induced acid stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042336 (2024).

Ikizler, T. A. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, S1–s107. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.006 (2020).

Mahboobi, S. et al. Effects of dietary interventions for metabolic acidosis in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol. Dialy. Transplantat. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfae200 (2024).

Shimamoto, S. et al. Association between proteinuria and mineral metabolism disorders in chronic kidney disease: the Japan chronic kidney disease database extension (J-CKD-DB-Ex). Sci. Rep. 14, 27481. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79291-5 (2024).

Sofue, T. et al. Prevalence of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease in japan: A nationwide, cross-sectional cohort study using data from the Japan chronic kidney disease database (J-CKD-DB). PLoS One. 15, e0236132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236132 (2020).

Bloom, B. M., Grundlingh, J., Bestwick, J. P. & Harris, T. The role of venous blood gas in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 21, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32836437cf (2014).

Nakagawa, N. et al. J-CKD-DB: a nationwide multicentre electronic health record-based chronic kidney disease database in Japan. Sci. Rep. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64123-z (2020).

Rajeev, D. et al. Development of an electronic public health case report using HL7 v2.5 to Meet public health needs. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 17, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M3299 (2010).

Kume, N., Suzuki, K., Kobayashi, S., Araki, K. & Yoshihara, H. Development of unified lab test result master for multiple facilities. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 216, 1050 (2015).

Kawazoe, Y., Imai, T. & Ohe, K. A querying method over RDF-ized health level seven v2.5 messages using life science knowledge resources. JMIR Med. Inf. 4, e12. https://doi.org/10.2196/medinform.5275 (2016).

Matsuo, S. et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 53, 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034 (2009). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kaori Ikemoto of the Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, Kawasaki Medical School, and Maiko Daisaka of the Department of Clinical Nutrition Science, Kidney Research Center, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan) Research on Medical ICT and Artificial Intelligence Program Grant Number JPMH19AC1002, Research on Renal Diseases Program Grant Number JPMH24FD1001, and AMED (Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development) under Grant Number JP20ek0210135, and a grant from the Tanuma Green House Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research idea and study design: MT, MH, HK, SI, SK, HN; data acquisition and analysis: SI, SK, HN; interpretation of the data: MT, MH, HK, SI, SK, HN; statistical analysis: SI, SK, HN; supervision or mentorship: SG, SY. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, M., Hosojima, M., Kabasawa, H. et al. Assessment and treatment of metabolic acidosis in CKD: a registry-based study. Sci Rep 16, 5104 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35335-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35335-6