Abstract

Bananas and plantains, part of the Musa genus, are key global food crops that are threatened by various factors, including hurricanes and microbial infections. The production of phytopathogen-free plants in Temporary Immersion Bioreactors (TIB) has gained attention due to improved yield and health. However, the impact of TIB on Musa spp. microbiomes remains poorly understood. Thus, elucidating the role of in vitro Musa spp. microbiome is crucial for developing healthier plantlets with beneficial microbes, such as plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), which are essential for plant development and might help Musa spp. thrive in abiotic and biotic stresses after in vitro development. To reveal the potential association of PGPB, we aimed to identify and characterize the bacterial communities from in vitro (TIB) Musa spp. varieties (Maiden, Dwarf, and Maricongo) pseudostems using both culture-independent (16S rDNA-metabarcoding) and culture-dependent methods to elucidate their diversity and roles in plant health. Our results identified four bacterial phyla, with Bacillota being the most dominant, followed by Pseudomonadota, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota. Brevibacillus sp. and Xylella sp. were the dominant genera. The isolates included Lysobacteraceae and Terribacillus spp., and the microbiomes metabolic pathways featured cofactors and amino acid biosynthesis. These findings enhance the understanding of bacterial communities in Musa spp. under in vitro conditions, highlighting the potential effects of artificial environments on host microbiomes, and encouraging innovative research into bacterial-plant interactions. This may aid in identifying specific bacteria with potential PGPB traits in Musa spp., offering new ways to enhance production and protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Musa spp. are a widely distributed plant genus around the world, including bananas and plantains, producing around an estimated 114 million tons per year, positioning them among the most essential monocultures1,2. Also, their nutritional richness, commercial value, and economic impact have positioned Asia, Africa, and Latin America as their major producers3. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are responsible for 28% of banana production worldwide, with an estimated local consumption of ~ 20 tons4. In Puerto Rico, plantains (Musa spp. AAB group) are recognized as one of the most consumed fruits on the Island, and their production signifies the sustainability of the overall agricultural sector within the region. The Puerto Rico Census of Agriculture estimated that local banana and plantain production generates an annual income of $56 million, producing around 180 thousand fruit units in Puerto Rico5. Although plantains have an important role in the food chain, several biotic and abiotic factors affect crop development6,7,8. Abiotic factors such as hurricanes are considered a main concern for plantain production in Puerto Rico, which was significantly impacted by Hurricanes Maria and Irma back in 2017 and 2022, respectively9,10. Besides abiotic factors, there are additional agricultural threats that can limit crop yields. Infections by phytopathogens, for example, are the major limitations for banana production in the LAC region11, due to the transmission/interaction of phytopathogens by conventional agricultural methods12. Thus, efforts have been focused on enhancing their productivity7. One of these phytopathogens, the Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 (FOC-TR4), possesses the ability to infect Musa spp. by colonizing the rhizosphere and entering through roots to target the vascular system of the plant, resulting in necrosis8,13,14,15. Additionally, their chlamydospores can remain latent in the soil for decades, and currently, no effective treatment, neither biological nor chemical are available for controlling their infection and dissemination4,8,16. However, plantain microbiome bacteria have been identified to fight some phytopathogens17. Thus, microbiome studies are pivotal to understanding the bacterial communities of plantain and their relationship with plant development, production, and protection against phytopathogens.

Microbiome studies in Musa spp. have been focused on revealing the bacterial communities associated with roots7,15. Notably, besides the roots, pseudostem and corm also gain contact with soil microbiome, including phytopathogens13. Therefore, previous studies have highlighted the importance of studying the endomicrobiome of general plant organs, including the pseudostem18. In this context, beneficial endophytic bacteria have been identified in plantain pseudostem with a capacity to fight phytopathogens and, in some cases, provide complete immunity against infection in the host17. Additionally, several studies have shown that environmental conditions and farming practices shape microbial diversity in the different organs of Musaspp7,19,20. In a recent study conducted by Birt et al.21, the emphasis was placed on elucidating the bacterial core microbiome of Musa spp. of different plant compartments, like corm, pseudostem, leaves, and the soil where they were cultivated. Their results suggested that Musa spp. is composed primarily of bacteria from the class Gammaproteobacteria that are known to be plant-associated, while promoting growth and overall host fitness22. Some studies have shown that Musa spp. genotypes can possess different microbiome compositions according to geographical locations, environmental conditions, and plant compartments4,21,22. However, some researchers argue that Musa spp. microbiome composition remains similar across various genotypes23,24,25. In contrast, recent studies indicate that edaphic conditions can change microbiomes even within the same genotypes21. As a result, microbiome studies of local varieties of Puerto Rico will be beneficial to understanding Musa spp. microbial diversity.

Agriculture conventional methods can transmit phytopathogens between plants and can limit crop yields12. These conventional approaches rely on vegetative reproduction, which increases the risk of acquiring, propagating, and disseminating harmful plant pathogens26. However, approaches for producing free-contaminant plants under in vitro conditions using Temporary Immersion Bioreactors (TIB) have been gaining interest due to the enhanced yield and overall health in plants developed by this method27,28,29. Previous study highlighted the importance of microbiome selection during in vitro plant development, which provides a controlled microenvironment for allowing plant-microbe interaction, favoring plant adaptation and immunity30. These advantages arise from the mutualistic relationship between plants and bacteria, commonly classified as Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB), that in most cases are responsible for improving plant yield, overall health, nutrient acquisition, and immunity against phytopathogens30,31. However, the effect of in vitro microenvironment shaping plantain microbiomes and the potential roles and functionality of bacteria under TIB conditions in plant development are poorly understood. Additionally, there is no publicly available research analyzing the microbiome of Musa spp. varieties cultivated in Puerto Rico, nor under in vitro conditions such as TIB.

For these reasons, this study aimed to characterize the bacterial communities of three Musa spp. varieties cultivated in Puerto Rico (i.e., Maricongo, Maiden, and Dwarf) using a culture-independent approach (i.e., 16 S rDNA metabarcoding) to provide insight into their composition and potential biological significance. However, viable bacteria characterization from in vitro Musa spp. has been mostly based on common bacterial contamination growth under in vitro conditions32, or the effect of adding synthetic communities to the plant33,34,35. Consequently, analyses of viable bacteria in Musa spp. from TIB system also remain unexplored. Thus, this study also characterized and isolated the viable bacteria from in vitro Musa spp. In this way, we provide data that suggest that PGPB are selected and in high abundance under in vitro conditions, which might increase Musa spp. fruit yield and plant immunity to phytopathogens.

Results

16S rDNA metabarcoding

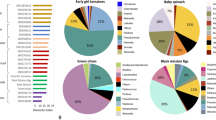

Total gDNA extracted from in vitro Musa spp. pseudostems/corms was sequenced (Fig. 1A), targeting on the 16S rDNA V3-V4 regions. The 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing of in vitro Musa spp. produced forward/reverse raw reads ranging between 111,295 and 217,179 reads (Supplementary Table 1). At the phylum level, most samples were dominated by Bacillota, followed by Pseudomonadota (Fig. 1D). In parallel, taxonomical assignment at the family level indicated a predominance of Xanthomonadaceae in Maricongo variety, followed by Brevibacillaceae in Maiden (Fig. 1B). Likewise, at the genus level, bacterial communities present in Musa spp. pseudostems demonstrated a high overall abundance of Xylella spp., whereas Prevotella spp. were less abundant (Fig. 1C). A high abundance of Xylella sp. was identified in all Maricongo variety replicates, while in Maiden and Dwarf were absent. Nevertheless, in Maiden, the most predominant features were Brevibacillus sp. and Succinivibrionaceae. Overall, the top 3 bacteria genera were Xylella sp., Brevibacillus sp., Faecalibacilum sp. core metrics at genus level showed the diversity, evenness, and richness of the bacterial communities in our samples.

Bacterial community composition associated with in vitro Musa spp. Schematic representation of in vitro Musa spp. pseudostem/corm tissues used for microbiome characterization (created with BioRender.com) (A). Taxonomic profiles at the phylum (B), family (C), and genus (D) levels show the composition and relative abundance patterns of bacterial communities associated with in vitro cultures of Musa spp. varieties.

Subsequently, alpha diversity metrics, applied to assess richness, diversity, and evenness, revealed significant differences in Faith’s Phylogenic Diversity (Faith’s PD), observed only between Maricongo and Dwarf (P = 0.049535) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, Shannon entropy showed no significant differences among samples (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the two additional metrics also indicated significant difference in Observed features (P = 0.043114 and 0.046302) and Pielou’s Evenness (P = 0.049535 and 0.049535) when comparing the bacterial communities of Musa spp. Maricongo with Maiden and Dwarf, respectively (Fig. 2C,D). Therefore, beta diversity two dimensional principal coordinate analysis (2D-PCoA) plots based on unweighted and weighted UniFrac dissimilarity showed no differences among the three varieties of Musa spp. bacterial communities structure (Fig. 2E,F). Although three Maricongo samples exist, only one dot appears in the weighted UniFrac plot because all three cluster at the same coordinate due to low variance. Finally, a comprehensive analysis of microbiome composition (ANCOM) was conducted at both the family and genus levels. This revealed differences in the abundance of Xanthomonadaceae and Pseudomonadaceae at the family level, and Xylella sp. and Pseudomonas sp. at the genus level among the tested Musa species (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Microbiome alpha and beta diversity metrics. Alpha diversity was evaluated using Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (Faith’s PD) (A), Shannon entropy index (B), Observed features (C), and Pielou’s evenness index (D), capturing phylogenetic richness, taxonomic diversity, species richness, and community evenness across samples, respectively. Pairwise Kruskal–Wallis analysis indicated no significant differences only in Shannon entropy (B). All alpha metric P-values are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Beta diversity was assessed using weighted (E) and unweighted (F) UniFrac 2D-PCoA plots, measuring variations in dominant taxa based on relative abundance and capturing presence/absence of rare/low abundant taxa, respectively. Pairwise PERMANOVA indicated no significant difference in both beta diversity metrics (E–F).

Functional analysis

Functional analysis of bacterial communities among in vitro Musa spp. showed the most dominant metabolic pathway. Overall, we identified 27 distinct general ontologies of metabolic pathways across all bacteria in our samples, totaling 288 pathways across all samples. These metabolic types include biosynthesis and degradation pathways (Fig. 3A). Notably, the top 5 most abundant pathways were classified into specific or other pathways. Specific pathway types included Cofactor-Biosynthesis (18.75%), Amino-Acid-Biosynthesis (11.46%), Energy-Metabolism (10.42%), Nucleotide-Biosynthesis (9.72%), and Lipid Biosynthesis (5.90%). Pathways with less than 1.5% of abundance were grouped as other pathways, which accounted for 9.72%. Relative differential enrichment analysis across all pairwise comparisons of general ontology metabolic pathway types (Fig. 3B) revealed that Maiden and Maricongo had 14 significantly different pathways, Dwarf and Maricongo had 7, and Maiden and Dwarf had 1, indicating almost no metabolic divergence. Overall, Maiden and Maricongo exhibited the greatest differences in the general metabolic ontology of bacteria. Differences were evaluated according to adjusted P-value (< 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4).

General Ontology of metabolic pathways. The overall distribution of metabolic pathway types within the microbiome of in vitro Musa spp. shows that the top five categories are Cofactor and Amino Acid Biosynthesis, Energy Metabolism, Nucleotide Biosynthesis, and Lipid Biosynthesis (A). A heatmap of hierarchical clustering of rlog-transformed DESeq2 values highlights 28 pathways with relative differential abundance across Musa spp. microbiomes (B). The Maricongo variety demonstrates more variation in overall metabolic pathways compared to Maiden and Dwarf varieties.

DNA barcoding and Biochemical analysis

Microbial growth was obtained from in vitro Musa spp. pseudostem tissues. A total of six distinctive colonies were described and purified (Supplementary Fig. 2). Microscopic evaluations using Gram stain of the six isolated showed bacilli cell morphology of different sizes in all samples, with the presence of both Gram positive and negative bacteria among the isolates (Supplementary Table 2). Sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene produced an average contig size of 1400 bp for all six isolates. Contigs comparison with NCBI database using BLAST resulted in the identification of all isolates with > 90% query coverage and > 89% identity similarity, with Terribacillus sp. being the most predominant bacteria identified in our samples, followed by Lysobacteraceae bacteria (Table 1). From an evolutionary and speciation perspective, phylogenetic analyses using Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Neighbor-Joining (NJ) revealed the relationship across isolated and references bacteria, while the NJ topology suggested modest phylogenetic proximity between the isolates Terribacillus spp. A1–A3 and certain Bacillus strains recognized for their plant growth-promoting abilities (Fig. 4). Conversely, the most distantly isolated among the phylogeny was Terribacillus sp. D2 and M1. A series of biochemical tests showed that all the isolates tested positive for catalase. Although most Terribacillus spp. could ferment glucose (A/K), the Terribacillus sp. isolated from Maricongo Musa sp. utilized a different carbon source, specifically peptone metabolism (K/K). Regarding motility, all isolates were non-motile (Supplementary Table 2).

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rDNA region of isolated bacteria form in vitro Musa spp. and comparison with previously known PGPB Bacillus spp. The proportion (%) of replicate trees where the related taxa grouped during the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is indicated next to the branches (A). The initial tree for the heuristic search was automatically generated by utilizing the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and BioNJ algorithms on a matrix of pairwise distances calculated using the Tamura-Nei model, subsequently choosing the topology with the highest log likelihood value (B).

Discussion

Gaining insights into the microbial communities of in vitro Musa spp. is essential for comprehending their potential biological roles and agricultural uses. This is vital for developing sustainable methods to increase crop yields and improve host immune health. Our research revealed the bacterial composition of Musa spp. during in vitro culture, as well as the overall functional metabolic pathway profile of the microbiome associated with Musa spp. pseudostem/corm. Uncovering pseudostem bacteria diversity is essential to understanding their potential role in plants, since pseudostem is a vital organ for nutrients and water movement through the plants, and is suggested to possess higher bacterial diversity in this microenvironment in comparison to other plants22. Hence, our study provides an insight into the diversity and richness of pseudostem-associated bacterial communities under in vitro TIB conditions, a system for which bacterial diversity and potential host benefits have been poorly understood.

In terms of diversity, a significant difference in alpha diversity was observed (Fig. 2), and overall bacterial community diversity among the tested cultivars. After filtering chloroplasts and mitochondria, the number of features was significantly reduced, which led to skipping rarefaction to avoid losing microbiome data, as suggested by McMurdie et al.36. 16S rDNA amplicon sequences identified four bacterial phyla across all tested cultivars, including Pseudomonadota, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, and Bacillota, consistent with previous reports in Musa spp. microbiome21,37. The most predominant phylum was Bacillota, followed by Pseudomonata, both previously referred to as Firmicutes and Proteobacteria respectively38; these findings align with earlier reports on Musa spp. microbiomes7,13,21,22. Thus, these results suggest that the TIB in vitro system might be offering optimal conditions, which include the bioavailability of plant and media carbohydrates for Bacillota to be in higher abundance, as a previous report indicated that Bacillota have a metabolic advantage that allows them to compete and dominate a niche with many sources of carbon39. Although this study primarily focuses on a biological context, using TIB offers an alternative method for simulating environmental conditions (air supply and enhanced gas exchange) to develop resilient Musa spp. plantlets. A recent study by Sambolín et al.28 highlighted increased plant size, higher multiplication rates, and enhanced transcripts related to photosynthesis, and thus, the current research offers insights into the potential beneficial bacteria that could be selected under the TIB microenvironment.

Notably, the presence of Brevibacillus was identified in the absence of Xylella sp. and vice-versa. These results suggest a potential antagonistic effect between these species. According to Liu et al.40 Brevibacillus sp. is considered a plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) and protects plants against potential phytopathogenic fungi, including the harmful banana fungus Fusarium spp. For example, bacteria in the genus Brevibacillus provide various advantages to plants, including nitrogen fixation, the production of phytohormones like Indole Acetic Acid (IAA), ammonia, and the release of antifungal substances41. These features may also activate plant immunity and induce systemic resistance (ISR). This protection mechanism is achieved by targeting pathogens with antimicrobial compounds, promoting niche competition, and depleting nutrients by the host’s beneficial microbiome42. Subsequently, ISR can be induced by antagonistic bacterial species against fungal phytopathogens, triggering various biochemical and molecular reactions, including alterations in pathogen related transcripts, tissue structural changes, and changes in protein conformation43. Therefore, ISR triggered by PGPB activates the plant immune system by producing Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), and stomatal closure44. In contrast, Xylella sp. is considered an agricultural threat due to its virulence factors45. Among the samples, we also detected a robust pattern of Xylella infection in all Maricongo varieties, suggesting a potential affinity with the host as past study suggested45. Although Xylella sp. was identified in all Maricongo varieties, Pseudomonas sp. was also present in all Maricongo varieties, suggesting a co-occurrence pattern that may contribute to the suppression of Xylella sp. via ISR in the host. Therefore, Pseudomonas spp. possess essential traits that enable plant protection by suppressing infections and combating diseases through the production of antimicrobial compounds, lytic enzymes, and organic substances46,47,48,49. This observation aligns with previous studies concerning biocontrol of Fusarium and many other phytopathogens by Pseudomonassp4,50,51.

Preventive research is crucial to providing a clear view of the potential protective capability of Musa spp. microbiome against potential phytopathogens such as FOC-TR452. Past studies using comparative microbiome approaches have shown that gammaproteobacterial microbiome shifts among healthy and infected Banana plants with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense race 14. In our study, data showed a pattern of low abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in Maiden and Dwarf when compared with Maricongo, which exhibited a high abundance of Xylella sp., a member of the Gammaproteobacteria. Hence, this might provide insight into potential molecular recognition patterns of innate immune system receptors that trigger a microbiome shift against specific bacterial families23. Additionally, a study by Köbert et al.4 reported that members of Gammaproteobacteria can serve as a health indicator in banana plants since this phylum was strictly found in healthy bananas when compared to diseased bananas with Fusarium. The study showed a shift in abundance by potential PGPB such as Stenotrophomonas and Pseudomonas in healthy plants, while diseased plants showed more affinity towards the Enterobacteriaceae family, commonly known to be detrimental to plant development. Despite this, the bacterial phylum (Pseudomonadota) is representative of healthy Musa spp. could also harbor phytopathogenic members known to cause disease, such as Xanthomonas campestris, the causal agent of Xanthomonas wilt21,53,54. However, these communities could be present in a latent stage55, while plants demonstrated asymptomatic phenotypes, supporting our findings. Although past reports suggest Gammaproteobacteria as a health indicator, here we demonstrated that a beneficial bacterial genus, such as Brevibacillus, a member of the phylum Bacillota, was the most abundant PGPB candidate. Importantly, the Bacillota phylum is thought to be crucial in fostering sustainable agriculture, as they can modulate plant growth and enhance protection56,57.

Although some researchers suggested that microbiomes are similar across genotypes in some plants23,24,25, Rochefort et al.58 have also shown that stem microbiota is not influenced by genotypes, strongly supporting our beta diversity results. Therefore, weighted and unweighted UniFrac analyses revealed no significant differences in bacterial community structure across samples, indicating that both dominant and rare taxa were broadly conserved among Musa spp. varieties. Consistently, PERMANOVA, showed no significant pairwise differences for either metric (Supplementary Table 3). Hence, our data reveal that taxa profiles were significantly different according to alpha diversity among the three cultivars tested. Notably, two of these cultivars were obtained from the Tropical Agricultural Research Station (TARS) of the USDA, at Mayagüez, P.R., and Maricongo was obtained from the Center of Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture, at the Inter American University of P.R. Barranquitas, P.R., and is very likely that the origin of the samples explants may vary in geographical location, thus supporting prior studies7,22 in which is suggested that geographical locations might play a crucial role in shaping the host microbiome. Our findings indicate that bacterial diversity, richness, and evenness across the tested cultivars under these conditions differ in species counts and overall distribution. Musa spp. Maricongo showed a significant difference in the evolutionary composition of its associated bacterial communities compared with Dwarf (Faith’s PD, P = 0.049535) and exhibited higher species richness than Maiden and Dwarf (Observed features, P = 0.043114 and 0.046302). The same pattern was observed in the evenness of the identified species across samples (Pielou evenness, P = 0.049535 and 0.049535), which could provide insights into how in vitro environments influence the microbiome. These findings support the fact suggested by Birt et al.21, which reported that the field growth of Musa spp. showed the absence of 11 Musa spp. core taxa candidates when compared with young Musa spp. in pots. Similarly, our results showed a total of 14 taxa, with only one (Pseudomonas sp.) previously identified as part of the core taxa of pot-grown Musa spp. in earlier research21. Additionally, just one (Pseudomonas sp.) matched with a Musa spp. microbiome meta-analysis across 22 prior studies across the world21. Although Cregger et al.25 and Birt et al.21 showed that overall microbiome varied primarily according to microhabitats regardless of genotypes, our evidence demonstrates that alpha diversity across microbiomes is strongly related to several factors, including environment, growth conditions, and variety. In addition, plant development also plays a crucial role in microbiome shifts according to their vegetative stage, due to changes in host metabolism, which impact bacterial communities among many plant compartments59. Specifically, in bananas has been evidenced that mother plants bacterial diversity can differ from its own suckers37, thus, showing the complexity of microbial diversity among several factors, including plant phenological stages.

Culture-dependent techniques exhibit inherent limitations concerning media composition and the viability of prokaryotic organisms60. Nevertheless, a total of six bacterial isolates were successfully characterized by employing culture-dependent methodologies in this study (Table 1). Interestingly, despite performing the amplicon sequencing, none of them were identified through 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing. Specifically, isolates Terribacillus spp. and Lysobacteraceae sp., were not detected by 16S rDNA metabarcoding. However, Terribacillus spp. are endospore-forming bacteria61. Thus, it is possible that these isolates were in their latent stage (endospore) within Musa spp. tissues under in vitro conditions, maintaining them undetectable by sequencing. This aligns with previous suggestions62, which indicates that spores can resist various DNA isolation protocols. As a result, approaches based on culture enabled these spores to germinate. Notably, some species of Terribacillus halophilus and Terribacillus saccharophilus have been isolated from soil63,64. In addition, Terribacillus goriensis was originally isolated from marine environments65,66, while Terribacillus aidingensis has been isolated from kimchi67, and sediments61, with Cryptomeria fortunei being the only reported source of isolation from plants68. Interestingly, contrary to ML phylogenetic tree, in NJ these isolates grouped within the Bacillus clade composed of known PGPB69. Despite clustering within the same clade, the NJ branch length value (0.3171) suggest considerable genetic divergence among Terribacillus spp. and Bacillus spp. This observation provides an insight into the potential PGPB species relationship that might be present in the tested Musa spp. paving the way for further research.

It is well established that bacteria can affect their hosts through their metabolites, interacting in both beneficial and harmful ways70. Predictions generated using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2 (PICRUSt2) revealed several significant metabolic pathways within the overall microbiome, predominantly characterized by anabolic and catabolic pathways, aligning with prior findings by Comeau et al.71. Although the predicted pathways are collectively identified among all the identified bacteria, some pathways may be associated with the identified bacteria through culture-dependent and independent approaches. For instance, the nucleotide biosynthesis pathway emerged as one of the top five, supporting the observation that Pseudomonas produces phospholipases that break down environmental phospholipids, thereby releasing phosphorus, an essential element for nucleotide biosynthesis71. Also, plants require amino acids for their physiological development as well as to manage stress72, which led our analysis to highlight amino acid-biosynthesis pathways among the top three in the overall microbial metabolic profile. This biosynthesis might also be connected to Brevibacillus sp. and Pseudomonas sp., which previous studies have documented as capable of synthesizing indole acetic acid (IAA), a plant hormone derived from the amino acid tryptophan, and has been previously associated with improvements in rice plants73,74. Additionally, cofactor biosynthesis is vital for plant growth; for instance, zinc serves as a crucial cofactor in about 300 plant enzymes. Evidence shows that Pseudomonas sp. can modify them for further molecular processes, classifying it as a zinc-solubilizing bacterium (ZSB)75. Furthermore, antifungal metabolites secreted by bacteria can originate from lipid precursors, aligning with our findings on lipid biosynthesis pathways. Notably, we identified aromatic compound degradation, potentially linked to Terribacillus spp., which Kim et al.66 noted for its potential in plastic degradation capabilities. These results are consistent with earlier studies70,75, highlighting the essential role of plant microbiome metabolism in enhancing hosts. Thus, the bacteria identified from in vitro Musa spp. and their characteristics align with previous findings, reinforcing their classification as plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB)40,73,74,75.

In summary, our research described the microbiome of three Musa spp. varieties and emphasizes the potential role of an in vitro culture system in shaping bacterial communities. This study enhances our comprehension of the microbiome’s response to artificial conditions, encouraging further investigation. Additionally, our results offer new perspectives on functional plant-microbe interactions within controlled environments, thus improving agricultural sustainability by identifying microbes that can enhance and protect plants. We strongly contend that various abiotic and biotic factors, including growth and environmental conditions, influence the microbiome composition in Musa spp. pseudostems. By revealing the bacterial composition of in vitro Musa spp., we observed a trend indicating a higher abundance of Brevibacillus sp., a potential plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) in Musa sp. Dwarf. This suggests that this variety, under the tested conditions, harbors beneficial bacteria, potentially making it less susceptible to stress from abiotic or biotic factors. Importantly, to our knowledge, this study identifies several Terribacillus spp. isolated for the first time from Musa spp. Consequently, our research opens an opportunity to investigate these microbes to characterize their plant-growth-promoting properties during in vitro and field conditions, aiding in clarifying their effectiveness in enhancing crop yield and protection. Hence, this study highlights the significance of integrating both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, as they complement one another in providing a robust and accurate understanding of the bacterial communities present within a host under specific conditions. Therefore, although the study was limited to the pseudostem of in vitro Musa spp., these findings advocate the application of both approaches in future research on other Musa spp. compartments.

Methods

Plant material

In vitro plantains (Musa spp. AAB group) were used for experimental procedures. Plantlets of three different varieties found in Puerto Rico were propagated in vitro using TIB following the protocol from Sambolín et al.28, and Aragon et al.27. In brief, plant materials were selected according to desired traits by farmers (i.e., fruit quality, productivity, organoleptic characteristics). Plant materials were obtained from two plant tissue culture facilities in Puerto Rico. Musa spp. Maricongo variety was acquired from the Center of Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico at Barranquitas, P.R., while Maiden (TARS 16511) and Dwarf super plantain (TARS 16507) varieties were acquired from the U.S. Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Services - Tropical Agriculture Research Station (USDA-ARS-TARS) at Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. Two independent groups of in vitro clones cultures were used for culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, due to the small amount of tissue that is produced and needed for downstream applications. Briefly, plant material for metabarcoding consisted of growing triplicates of each Musa spp. (i.e., Maiden, Dwarf, Maricongo) with size of < 42 mm in the multiplication phase, which were subcultured for ~ 3 growth cycles in regeneration media. Growth room parameters were set to mimic a summer with a photoperiod of 16:8 h, temperature varying from 29 °C ± 1 °C, light intensity ranging from 5513 to 5370 lux (Phillips F32T8/TL965 light bulb, Andover, USA), and immersion times of 3 min every 4 h. Moreover, for culture-dependent approach, the same conditions were applied with minor changes; triplicates of all varieties consistent with a size of < 40 mm and light intensity ranging from 4945–5048 lux. All plant materials were established and cultured until vigorous and healthy growth (i.e., shoot formation and stem elongation) was perceived before applying any laboratory procedure.

DNA isolation and sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) isolation was carried out according to previous studies for plant microbiome analysis21,76, with minor modifications. In brief, fresh in vitro Musa spp. plantlets were excised, and only the pseudostem/corm section was processed. Tissues were macerated and homogenized using a micro-pestle and vortexing at full speed for 2 min inside a power bead tube (Qiagen ©). gDNA was isolated using DNeasy Power Soil Kit (Qiagen ©). All genomic DNA isolations were made in triplicate for each variety (n = 9). Qualitative and quantitative analyses were applied to all the gDNA samples using a Bio-Spec nanophotometer (Shimadzu ©). DNA integrity was verified through gel electrophoresis with 1% agarose using TBE 1X buffer. Gel was stained using 2 µl of ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml) per 25 ml of 1% agarose and visualized in ChemiDoc (BioRad). High-throughput sequencing was carried out by Novogene (Beijing, China) with the NovaSeq X6000 sequencing platform, generating paired-end reads of 250 bp of the V3-V4 region of the 16S rDNA using 341 F-806R primers.

Bioinformatics

Musa spp. pseudostem/corm microbiome raw data analysis was performed following previously published pipelines21,77,78 with minor modifications, such as skipping rarefaction. Briefly, raw FASTQ files were processed and analyzed using QIIME2 v2024.277, with the Casava18 format for generating the contigs. Metabarcoding libraries were demultiplexed, and both reads were trimmed to 224 bp (forward) and 219 bp (reverse) achieving a median Phred quality score of Q37. Denoising was employed using DADA279 to correct sequences, remove chimeras, and merge sequences. As a result, Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) of 443 bp in length were produced and used for further analyses. Taxonomical profile and classification were generated using SILVA-release-138-nr99-SSU. A filtering step was applied to remove detected chloroplasts and mitochondria from all samples. Since in vitro plants possess very low richness and microbial communities compared to field conditions, rarefaction was skipped to avoid losing data in our samples. Subsequently, a Kruskal-Wallis pairwise test was conducted on several alpha diversity metrics, including Shannon entropy80, Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity81 (Faith’s PD), Pielou Index82, and Observed Features83. The significance of beta diversity was assessed using unweighted and weighted UniFrac84 analyses along with pairwise PERMANOVA. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was used to illustrate potential dispersion and clustering of Musa spp. samples based on the dissimilarity matrix of microbiomes. Lastly, Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes (ANCOM)85 was employed to identify bacteria that were differentially abundant among the samples tested. The predicted functional profile of general metabolic pathways across all bacterial communities was based on PICRUSt286 and analyzed using DESeq2 (1.38.1)87,88, with pseudo-counts added and integer coercion, conducted at a 95% confidence level. The size factor estimation was performed using post-counts methods, and the log2 Fold Change (log2FC) were moderated using apeglm shrinkage (1.28.0). A heatmap and hierarchical cluster were generated using ggplot2 (4.0.1) and pheatmap (1.0.13) libraries on RStudio (4.4.1). All graphs were visualized using GraphPad Prism (10.4.2).

Isolation of viable bacteria and phenotypic characterization

Conventional culture methods were applied to isolate viable bacteria from in vitro Musa spp. according to Li et al.89, adapted to our conditions. In short, all varieties of Musa spp. were cultured in vitro for a growth cycle of ~ 30 days. Laboratory conditions during in vitro culture of Musa spp. were 16:8 photoperiod, light intensity of 4945–5048 lux, and temperatures of 29 °C ± 2 °C. In brief, ~ 100 mg of each pseudostem/corm tissue was homogenized in a 1.5 ml microtube with a micro-pestle previously disinfected. Following homogenization, a serial dilution (10− 1–10− 3) was performed in 0.85% saline solution. The spread plate technique was employed to inoculate serial dilution homogenate on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates in triplicate for each variety. To mimic the tissue culture growth room, TSA plates were incubated for 72 h at 29 °C ± 2 °C. Lastly, bacterial colonies were described based on their macro/microscopical characteristics. Finally, the most different and abundant colonies were identified and selected for purification by streak plate in TSA.

DNA barcoding and biochemical characterization

To get high biomass for gDNA isolation, a fresh culture (72 h) of the 6 unknown isolated bacteria was used. The gDNA isolation was carried out using the Zymo Research Bacterial/Fungal DNA extraction Kit (Zymo). The integrity of gDNA was validated by gel electrophoresis in 1% TBE 1X agarose (85 V, 1 amp, ~ 50 min); ethidium bromide was used as a detection dye for nucleic acids in samples and visualized using ChemiDoc (BioRad). Subsequently, the majority of the 16S rDNA region was amplified using a PCR reaction with primers 27 F and 1492R90,91, yielding an expected product of approximately 1500 bp. PCR reaction of 15 µl consisted of 1X of Q5 Hot-Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (NEB Biolabs), 1 µl of genomic DNA (24–163ng/µl), 0.5 µM of each oligonucleotide (27 F and 1492R), and molecular grade H2O up to 15 µl. Thermocycler conditions were set to an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min and an infinite hold of 4 °C. PCR amplicons were sent to Azenta Life Science (South Plainfield, NJ, USA), for sequencing the 16S rDNA region using the Sanger sequencing platform. FASTA files were obtained, and both amplified strands were merged using CodonCode Aligner 11.0.2 (CodonCode Corp., Centerville, MA ,USA). Generated contigs were then examined using the NCBI tool Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Multiple sequence alignments were done using Muscle on MEGA71 (10.1.8) for the phylogenetic tree construction using Maximum Likelihood (1000 bootstraps69 and Neighbor-Joining along with BioNJ following Tamura model92 for analyzing evolution and speciation events. Lastly, conventional methods were employed to gain insight into the metabolic characteristics of isolated bacteria. Fresh bacterial cultures were growth and inoculate in different media to evaluate their metabolic profile. Biochemical assays included the Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) test, which uses color changes to indicate changes in pH and sugar fermentation. Catalase test: A positive result is indicated by the release of oxygen, and SIM motility demonstrates bacterial movement through observed turbidity after inoculation. All tests were performed following previous recommendations93,94,95.

Data availability

The 16S rDNA amplicon sequences were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the Bio-Project accession number PRJNA1226154. Individual Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers were provided in the supplementary Table 1. Isolated bacterial complete 16 S barcode accession numbers are also provided in Table 1.

References

FAO. The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2018: Agricultural Trade, Climate Change and Food Security (Rome, Italy 2018). https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/69ad8e6b-d722-4592-a29d-68c035cc0c50.

FAO. Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets (FAO, 2022). https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9427en

Leonel, S. et al. Achievements of banana (Musa sp.)-based intercropping systems in improving crop sustainability. Horticulturae 10, 956 (2024).

Köberl, M., Dita, M., Martinuz, A., Staver, C. & Berg, G. Members of Gammaproteobacteria as indicator species of healthy banana plants on fusarium wilt-infested fields in central America. Sci Rep 7, 45318 (2017).

USDA. USDA releases 2022 Puerto Rico Census of Agriculture (2022). https://www.nass.usda.gov/Newsroom/2024/07-18-2024.php

Ploetz, R. C. Fusarium wilt of banana. Phytopathology® 105, 1512–1521 (2015).

Kaushal, M. et al. Subterranean microbiome affiliations of plantain (Musa spp.) under diverse agroecologies of Western and central Africa. Microb. Ecol. 84, 580–593 (2022).

Dale, J. et al. Transgenic Cavendish bananas with resistance to fusarium wilt tropical race 4. Nat Commun 8, 1496 (2017).

Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A. & Niles, M. T. (PDF) Hurricane Maria’s impacts on Puerto Rican farmers: Experience, challenges, and perceptions. ResearchGate (2018). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333204111_Hurricane_Maria’s_Impacts_on_Puerto_Rican_Farmers_Experience_Challenges_and_Perceptions

Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A., Álvarez-Berríos, N. & Niles, M. T. Social-ecological interactions in a disaster context: Puerto Rican farmer households’ food security after hurricane Maria. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 044057 (2022).

Dita, M. A., Garming, H., Van den Bergh, I., Staver, C. & Lescot, T. Banana in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current state, challenges and perspectives. Acta Hortic. 986, 365–380 (2013).

Roels, S. et al. Optimization of plantain (Musa AAB) micropropagation by temporary immersion system. Plant. Cell. Tissue Organ. Cult. 82, 57–66 (2005).

Kaushal, M., Mahuku, G. & Swennen, R. Metagenomic insights of the root colonizing microbiome associated with symptomatic and non-symptomatic bananas in fusarium wilt infected fields. Plants 9, 263 (2020).

Pegg, K. G., Coates, L. M., O’Neill, W. T. & Turner, D. W. The epidemiology of fusarium wilt of banana. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 1395 (2019).

Tharanath, A. C., Upendra, R. S. & Rajendra, K. Soil symphony: A comprehensive overview of plant–microbe interactions in agricultural systems. Appl. Microbiol. 4, 1549–1567 (2024).

Garcia, R. O., Rivera-Vargas, L. I., Ploetz, R., Correll, J. C. & Irish, B. M. Characterization of fusarium spp. Isolates recovered from bananas (Musa spp.) affected by fusarium wilt in Puerto Rico. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 152, 599–611 (2018).

Suhaimi, N. S. M. et al. Diversity of microbiota associated with symptomatic and non-symptomatic bacterial wilt-diseased banana plants determined using 16S rRNA metagenome sequencing. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 168 (2017).

Vimal, S. R., Singh, J. S., Kumar, A. & Prasad, S. M. The plant endomicrobiome: structure and strategies to produce stress resilient future crop. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 6, 100236 (2024).

Peiffer, J. et al. (ed, A.) Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere Microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110 6548–6553 (2013).

Shakya, M. et al. A multifactor analysis of fungal and bacterial community structure in the root Microbiome of mature Populus deltoides trees. PLoS One. 8, e76382 (2013).

Birt, H. W. G. et al. The core bacterial microbiome of banana (Musa spp). Environ. Microbiome. 17, 46 (2022).

Köberl, M. et al. The banana microbiome: Stability and potential health indicators. Acta Hortic. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2018.1196.1 (2018).

Bulgarelli, D. et al. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe 17, 392–403 (2015).

Edwards, J. et al. Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112, E911–E920 (2015).

Cregger, M. A. et al. The Populus holobiont: Dissecting the effects of plant niches and genotype on the microbiome. Microbiome 6, 31 (2018).

Aviles-Noriega, A., Serrato-Diaz, L. M., Giraldo-Zapata, M. C. & Cuevas, H. E. Rivera-Vargas, L. I. The Sigatoka disease complex caused by Pseudocercospora spp. and other fungal pathogens associated with Musa spp. in Puerto Rico. Plant. Dis. 108, 1320–1330 (2024).

Aragón, C. E. et al. Comparison of plantain plantlets propagated in temporary immersion bioreactors and gelled medium during in vitro growth and acclimatization. Biol. Plant. 58, 29–38 (2014).

Sambolín, C. A. et al. Biochemical and molecular characterization of Musa sp. Cultured in temporary immersion bioreactor. Plants 12, 3770 (2023).

Uma, S., Karthic, R., Kalpana, S., Backiyarani, S. & Saraswathi, M. S. A novel temporary immersion bioreactor system for large scale multiplication of banana (Rasthali AAB-Silk). Sci. Rep. 11, 20371 (2021).

Guardiola-Márquez, C. E. et al. Identification and characterization of beneficial soil microbial strains for the formulation of biofertilizers based on native plant growth-promoting microorganisms isolated from northern Mexico. Plants 12, 3262 (2023).

Hakim, S. et al. Rhizosphere engineering with plant growth-promoting microorganisms for agriculture and ecological sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 617157 (2021).

El-Banna, A. N. et al. Endophytic bacteria in banana in vitro cultures: molecular identification, antibiotic susceptibility, and plant survival. Horticulturae 7, 526 (2021).

Kavino, M. et al. Rhizosphere and endophytic bacteria for induction of systemic resistance of banana plantlets against bunchy top virus. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 39, 1087–1098 (2007).

Kavino, M. et al. Enhancement of growth and panama wilt resistance in banana by in vitro co-culturing of banana plantlets with PGPR and endophytes. Acta Hortic. 1024, 277–282 (2014).

Kavino, M. & Manoranjitham, S. K. In vitro bacterization of banana (Musa spp.) with native endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial isolates: Novel ways to combat fusarium wilt. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 151, 371–387 (2018).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Waste not, want not: Why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003531 (2014).

Gómez-Lama Cabanás, C. et al. The banana root endophytome: differences between mother plants and suckers and evaluation of selected bacteria to control Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. Cubense. J. Fungi (Basel). 7, 194 (2021).

Oren, A. On validly published names, correct names, and changes in the nomenclature of phyla and genera of prokaryotes: A guide for the perplexed. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 20 (2024).

Sharmin, F., Wakelin, S., Huygens, F. & Hargreaves, M. Firmicutes dominate the bacterial taxa within sugar-cane processing plants. Sci. Rep. 3, 3107 (2013).

Liu, Y., Zai, X., Weng, G., Ma, X. & Deng, D. Brevibacillus laterosporus: A probiotic with important applications in crop and animal production. Microorganisms 12, 564 (2024).

Nehra, V., Saharan, B. S. & Choudhary, M. Evaluation of Brevibacillus brevis as a potential plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) crop. SpringerPlus 5, 948 (2016).

Vlot, A. C. et al. Systemic propagation of immunity in plants. New Phytol. 229, 1234–1250 (2021).

Pandin, C. et al. Biofilm formation and synthesis of antimicrobial compounds by the biocontrol agent Bacillus velezensis QST713 in an Agaricus bisporus compost micromodel. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 85, e00327-19 (2019).

Aziz, A. et al. Effectiveness of beneficial bacteria to promote systemic resistance of grapevine to gray mold as related to phytoalexin production in vineyards. Plant. Soil. 405, 141–153 (2016).

Castro, C., DiSalvo, B. & Roper, M. C. Xylella fastidiosa: A reemerging plant pathogen that threatens crops globally. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009813 (2021).

Hernández-León, R. et al. Characterization of the antifungal and plant growth-promoting effects of diffusible and volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains. Biol. Control. 81, 83–92 (2015).

Lahlali, R. et al. Biological control of plant pathogens: A global perspective. Microorganisms 10, 596 (2022).

Validov, S. et al. Antagonistic activity among 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescentPseudomonasspp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 242, 249–256 (2005).

Vivekananthan, R., Ravi, M., Ramanathan, A. & Samiyappan, R. Lytic enzymes induced by Pseudomonas fluorescens and other biocontrol organisms mediate defence against the anthracnose pathogen in mango. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 235–244 (2004).

Xue, C. et al. Manipulating the banana rhizosphere Microbiome for biological control of Panama disease. Sci. Rep. 5, 11124 (2015).

Gaete, A. et al. Bioprospecting of plant growth-promoting traits of Pseudomonas sp. Strain C3 isolated from the Atacama desert: Molecular and culture-based analysis. Diversity 14, 388 (2022).

Were, E., Viljoen, A. & Rasche, F. Back to the roots: Understanding banana below-ground interactions is crucial for effective management of fusarium wilt. Plant. Pathol. 72, 19–38 (2023).

Blomme, G. et al. Bacterial diseases of bananas and enset: Current state of knowledge and integrated approaches toward sustainable management. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1290 (2017).

Jamil, F. N., Hashim, A. M., Yusof, M. T. & Saidi, N. B. Analysis of soil bacterial communities and physicochemical properties associated with Fusarium wilt disease of banana in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 12, 999 (2022).

Ehrlich, G. D., Hiller, N. L. & Hu, F. Z. What makes pathogens pathogenic. Genome Biol. 9, 225 (2008).

Aguilar-Paredes, A. et al. Microbial community in the composting process and its positive impact on the soil biota in sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 13, 542 (2023).

Hashmi, I., Bindschedler, S. & Junier, P. Chapter 18—Firmicutes. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology (eds Amaresan, N., Kumar, S., Annapurna, M., Kumar, K. & Sankaranarayanan, A.K.) 363–396 (Academic, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823414-3.00018-6

Rochefort, A. et al. Transmission of seed and soil microbiota to seedling. mSystems 6, 10–1128 (2021).

Doherty, J. R., Crouch, J. A. & Roberts, J. A. Plant age influences microbiome communities more than plant compartment in greenhouse-grown creeping bentgrass. Phytobiomes J. 5, 373–381 (2021).

Bonnet, M., Lagier, J. C., Raoult, D. & Khelaifia, S. Bacterial culture through selective and non-selective conditions: The evolution of culture media in clinical microbiology. New. Microbes New. Infections. 34, 100622 (2020).

Liu, W., Jiang, L., Guo, C. & Yang, S. S. Terribacillus aidingensis sp. nov., a moderately halophilic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. MicroBiol. 60, 2940–2945 (2010).

Filippidou, S. et al. Under-detection of endospore-forming Firmicutes in metagenomic data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 299–306 (2015).

Hauser, T. et al. Genome-based reclassification of Terribacillus goriensis (Kim et al. 2007) Krishnamurthi and Chakrabarti 2009 as a later heterotypic synonym of Terribacillus saccharophilus An et al. 2007. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 75, 006794 (2025).

An, S. Y., Asahara, M., Goto, K., Kasai, H. & Yokota, A. Terribacillus saccharophilus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Terribacillus halophilus sp. nov., spore-forming bacteria isolated from field soil in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. MicroBiol. 57, 51–55 (2007).

Su, Z. et al. Complete genome sequences of one salt-tolerant and petroleum hydrocarbon-emulsifying Terribacillus saccharophilus Strain ZY-1. Front. Microbiol. 13, 932269 (2022).

Kim, S. H. et al. Acceleration of polybutylene succinate biodegradation by Terribacillus sp. JY49 isolated from a marine environment. Polymers 14, 3978 (2022).

Na, H. E., Heo, S., Lee, G., Kim, T. & Jeong, D. W. Complete genome sequence of Terribacillus aidingensis DMT04 isolated from the Korean traditional fermented vegetables, Kimchi. Korean J. Microbiol. 58, 49–52 (2022).

Lu, P., Lei, M., Xiao, F., Zhang, L. & Wang, Y. Complete genome sequence of Terribacillus aidingensis strain MP602, a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from cryptomeria Fortunei in Tianmu mountain in China. Genome Announc. 3, e00126–e00115 (2015).

Ikeda, A. C. et al. Bioprospecting of elite plant growth-promoting bacteria for the maize crop. Acta Sci. Agron. 42, e44364 (2020).

Chen, Q., Song, Y., An, Y., Lu, Y. & Zhong, G. Mechanisms and impact of rhizosphere microbial metabolites on crop health, traits, functional components: A comprehensive review. Molecules 29, 5922 (2024).

Comeau, D. et al. Interactions between Bacillus Spp., Pseudomonas Spp. and Cannabis sativa promote plant growth. Front. Microbiol. 12, 715758 (2021).

da Fonseca-Pereira, P., Monteiro-Batista, R., de Araújo, C., Nunes-Nesi, A. & W. L. & Harnessing enzyme cofactors and plant metabolism: An essential partnership. Plant. J. 114, 1014–1036 (2023).

Sultana, R., Jashim, A. I. I., Islam, S. M. N., Rahman, M. H. & Haque, M. M. Bacterial endophyte Pseudomonas mosselii PR5 improves growth, nutrient accumulation, and yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) through various application methods. BMC Plant. Biol. 24, 1030 (2024).

Naik, P. R., Sahoo, N., Goswami, D., Ayyadurai, N. & Sakthivel, N. Genetic and functional diversity among fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from the rhizosphere of banana. Microb. Ecol. 56, 492–504 (2008).

Sethi, G. et al. Enhancing soil health and crop productivity: The role of zinc-solubilizing bacteria in sustainable agriculture. Plant. Growth Regul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-025-01294-7 (2025).

Aliche, E. B., Talsma, W., Munnik, T. & Bouwmeester, H. J. Characterization of maize root microbiome in two different soils by minimizing plant DNA contamination in metabarcoding analysis. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 57, 731–737 (2021).

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Estaki, M. et al. QIIME 2 enables comprehensive end-to-end analysis of diverse microbiome data and comparative studies with publicly available data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 70, e100 (2020).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 61, 1–10 (1992).

Pielou, E. C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 13, 131–144 (1966).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Mandal, S., van Treuren, W., White, R. A., Eggesbø, M., Knight, R. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 26, 27663 (2015).

Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685–688 (2020).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Schultz, C. R. et al. Effects of inbreeding on microbial community diversity of Zea mays. Microorganisms 11, 879 (2023).

Li, A. Z. et al. Culture-dependent and -independent analyses reveal the diversity, structure, and assembly mechanism of benthic bacterial community in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2523 (2019).

Heuer, H., Krsek, M., Baker, P., Smalla, K. & Wellington, E. M. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3233–3241 (1997).

dos Santos, H. R. M., Argolo, C. S., Argôlo-Filho, R. C. & Loguercio, L. L. A 16S rDNA PCR-based theoretical to actual delta approach on culturable mock communities revealed severe losses of diversity information. BMC Microbiol. 19, 74 (2019).

Tamura, K. & Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 512–526 (1993).

Reiner, K. Catalase Test Protocol. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Available at: https://asm.org/getattachment/72a871fc-ba92-4128-a194-6f1bab5c3ab7/catalase-test-protocol.pdf (2010).

Shields, P. & Cathcart, L. Motility Test Medium Protocol. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Available at: https://asm.org/asm/media/protocol-images/motility-test-medium-protocol.pdf?ext=.pdf (2011).

Lehman, D. Triple Sugar Iron Agar Protocols. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Available at: https://asm.org/asm/media/protocol-images/triple-sugar-iron-agar-protocols.pdf?ext=.pdf (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted at the Institute of Sustainable Biotechnology at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico, Barranquitas (IAUPR-BR), in collaboration with the Microbial Biotechnology and Bioprospecting Laboratory, Biology Department at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, P.R. We extend our sincere appreciation to all collaborators on this project, and special thanks to the Tropical Agricultural Research Station (TARS) of the USDA in Mayagüez, P.R., for providing the requested plant material. We also acknowledge the support from the U.S. Department of Education, DHSI TITLE V, Award No. P031S220125, for funding part of this project and involving undergraduate students.

Funding

The research and open access were supported by the Department of Science and Technology at the IAUPR-BR, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Education, DHSI TITLE V, Award No. P031S220125.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design, microbiome DNA isolation, bacterial isolation, bioinformatics analysis, and initial manuscript draft were carried out by C.A.S.P. Bacterial DNA isolation was performed by H.M.M.J., S.M.M.J., and Y.R.M. Furthermore, C.A.S.P., H.M.M.J., S.M.M.J., and Y.R.M. meticulously analyzed the results. R.A.B provided experimental support and laboratory materials. Revision, proofreading, and editing of the manuscript were carried out by A.R.N.M., C.R.V., and R.E.R.V. General advice regarding the study was provided by C.R.V., R.E.R.V., and J.A.N.B. Funding acquisition A.R.N.M. It is noted that all authors are aware of this study, and the respective authors reviewed the manuscript comprehensively.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sambolín-Pérez, C.A., Montes-Jiménez, S.M., Montes-Jiménez, H.M. et al. Revealing and characterizing bacterial communities of in vitro Musa species through 16S rDNA metabarcoding and culture dependent approaches. Sci Rep 16, 5214 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35510-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35510-9