Abstract

This paper presents a numerical meshless approach for solving the two-dimensional Allen-Cahn equation, utilizing a radial basis function-compact finite difference (RBF-CFD) method in combination with the Strang splitting technique. The Allen-Cahn equation is crucial for modeling phase transitions and interface dynamics, making its numerical solution essential for applications in materials science, fluid dynamics, and biology. For spatial discretization, we employ the RBF-CFD method, which provides high-order accuracy. Specifically, the Hermite RBF interpolation technique is used to approximate the model operators over local stencils. For temporal discretization, we apply the Strang splitting method, which improves both accuracy and efficiency by decomposing the equation into simpler components. This approach is particularly effective for handling nonlinear equations and complex systems, ensuring the preservation of physical properties while minimizing numerical errors. To assess the method’s performance, we conduct several numerical simulations to evaluate accuracy, stability, and convergence across different configurations. The results highlight the method’s ability to maintain key qualitative properties, such as energy decay over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Allen-Cahn (AC) equation, which emerged to simulate phase separation phenomena in binary alloys, governs the spatial and temporal evolution of the order parameter \(u(t,\varvec{x})\)1,2,3. This parameter serves as a phase field variable that characterizes different phases in diverse physical systems. This equation is widely used to model phase transitions and the dynamics of interfaces in fluid dynamics, materials science, and biological systems1,2,4,5. In two dimensions, the AC equation is expressed as:

where \(F(u) = 0.25(1 - u^2)^2\) denotes the double well potential, \(u(t, \varvec{x})\) indicates the phase field at \(\varvec{x}\), and \(\Omega \subset \mathbb {R}^2\) represents the two-dimensional spatial domain. The term \(\frac{F'(u)}{\varepsilon ^2}\) captures the phase transition, with \(\varepsilon\) governing the width of the interface between the two stages.

The AC equation is mathematically characterized as a gradient flow within the \(L^2\)-inner product space, corresponding to the minimization of the Ginzburg–Landau free energy functional:

The system’s total energy, represented by the functional \(E(u)\), decreases over time until it reaches a minimum at equilibrium. This is shown by taking the time derivative of \(E(u)\), which reveals that the energy never increases as follows:

To solve the AC equation, we begin by defining the initial condition for the phase field \(u(0, \varvec{x})\), representing the system’s state at the starting time. This condition is typically expressed through a predefined function \(u_0(\varvec{x})\) that specifies the spatial distribution of the phase at \(t = 0\). The initial configuration is formally given by:

where \(u_0(\varvec{x})\) is selected based on the physical problem being modeled.

Despite the significant interest in finding analytical solutions, a general analytical solution for this nonlinear equation remains unavailable. This gap highlights the importance of developing efficient numerical methods in solving the AC equation. In addition, obtaining numerical solutions for the AC equation is challenging. Therefore, advancing numerical techniques for this problem is essential to address theoretical challenges and facilitate practical applications in science and engineering.

In recent studies, many numerical techniques have been proposed by researchers. For instance, Poochinapan and Wongsaijai in6 developed a fourth-order compact difference scheme for one- and two-dimensional Allen–Cahn problems, treating the nonlinearity via a hybrid Crank–Nicolson and Adams–Bashforth framework. Lee et al.7 and Kim et al.8 proposed explicit finite difference methods, with the latter integrating graphics processing unit (GPU) acceleration and convolutional operations to boost computational efficiency. In9, the authors examined numerical solutions that are energy-dissipative and mass-conservative for simulating the evolution of phase separation dynamics, energy decay, and mass preservation. Lan et al.10 addressed the mass-conserving convective Allen–Cahn equation that is central to multiphase fluid modeling, by devising structure-preserving operator-splitting schemes. Additionally, Lee et al.11 formulated a high-order, unconditionally energy-stable method using a nonlocal Lagrange multiplier to enforce mass conservation and energy dissipation simultaneously. These efforts collectively advance the accuracy, stability, and applicability of numerical solutions for the Allen–Cahn equation.

The design of numerical methods that strictly preserve physical principles, such as energy dissipation and structure preservation, remains a central challenge, especially for complex gradient flows and dynamic systems12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Recently, various techniques were proposed to solve the AC equation, including the meshless RBF method19, localized RBF method20, maximum principle-preserving computational algorithms21, explicit numerical methods on cubic surfaces22, high-order Runge-Kutta schemes23, dimension splitting methods for two-phase flows24, third-order accurate schemes25, stability analysis via bifurcation and perturbation26, Crank-Nicolson schemes27, and linear second-order maximum bound principle-preserving schemes28.

Radial basis function-based techniques have been developed over recent decades as flexible computational tools for addressing diverse classes of partial differential equations (PDEs). These methods are recognized as rigorous tools for tackling high-dimensional problems, particularly for approximating scattered data. The growing importance of such meshless approaches in numerical methods for PDEs is due to their intrinsic advantages, including scalability to higher dimensions, adaptability to unstructured data, and the potential for spectral convergence rates. Some recent works employing RBF-based methods include the analysis of nonlinear Sobolev equations29, the investigation of generalized biharmonic equations under Cahn–Hilliard conditions30, introduction of the direct RBF partition of unity method for solving surface PDEs31, and the use of localized RBF approaches for incompressible two-phase fluid flows32. Additionally, meshless RBF-finite difference (RBF-FD) methods have been applied for 3D simulations in selective laser melting33, while inverse Cauchy problems have been solved using RBF techniques34.

Several investigations have explored local meshless techniques for solving various problems such as elliptic PDEs subject to multipoint boundary conditions35, Sobolev equations incorporating Burgers-type nonlinearity36, and coupled Klein–Gordon–Schrödinger equations37. Local methods based on the RBFs present distinct advantages over their global counterparts in the context of solving PDEs. By focusing on the local regions, these methods often require fewer computations compared to global methods that need to consider the entire domain. This efficiency is crucial for large-scale problems. Furthermore, local RBF methods allow for adaptive refinement, making them more effective in handling complex geometries and varying solution behaviors38,39.

Furthermore, the RBF-CFD method has proven effective in addressing computational challenges associated with global methods to solve differential equations40, demonstrating their versatility in applications such as solving Sobolev equations related to fluid dynamics41, and reaction-diffusion equations on surfaces42. The compact RBF-based partition of unity method based on the polyharmonic spline kernels is proposed in43.

In this study, the RBF-CFD method is applied to solve two-dimensional AC equations. The RBF-CFD method is employed for spatial discretization of the problem, while the Strang splitting method is utilized for temporal discretization. The Strang splitting strategy is an effective method for solving differential equations, particularly useful for nonlinear equations and complex systems44. This method works by decomposing the equation into simpler components and solving each part separately, enhancing both accuracy and efficiency in simulating the dynamics of systems. Its importance lies in its ability to preserve the physical characteristics of the system and reduce numerical errors, making it especially valuable for long-term and complex simulations45,46,47,48. An overview of recent studies on numerical techniques for the AC equation is presented in Table 1.

Despite the significant advancements, developing highly accurate, efficient, and meshless numerical schemes that effectively handle the stiff nonlinear terms of the 2D Allen-Cahn equation while preserving critical physical properties is essential. The localized RBF-FD methods, while addressing the ill-conditioning of global RBFs, often exhibit some shortcomings in accuracy. Consequently, this study presents an innovative approach by coupling the high-order RBF-CFD method for spatial discretization with the highly efficient and accurate Strang splitting method for temporal discretization. This proposed method offers spectral-like accuracy on scattered nodes, which is a significant improvement over standard second-order local RBF-FD or conventional low-order finite difference methods, while avoiding the matrix density issues of global RBFs. Furthermore, the integration of the Strang splitting method effectively decomposes the AC equation into a linear part and a non-linear part. This approach significantly enhances computational efficiency by allowing implicit handling of the stiff linear term and explicit handling of the nonlinear term, which is crucial for long-term simulations. The proposed scheme rigorously preserves the fundamental energy decay law of the Allen-Cahn equation, a key physical characteristic.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section “RBF-CFD formulas” introduces the RBF-CFD method, focusing on the formulation of the RBF-CFD weights. In “Discrete setting: application of RBF-CFD weights and strang splitting method”, we provide a detailed description of the numerical implementation, in which the spatial domain is discretized using the RBF-CFD method, and the Strang splitting technique is employed to efficiently split and solve the nonlinear and linear components in time. Section “Test examples” presents a series of numerical experiments to evaluate the accuracy, convergence, and robustness of the proposed method. Finally, Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and highlighting the method’s effectiveness in capturing the dynamic behavior of solutions to the Allen–Cahn equation.

RBF-CFD formulas

In this section, we discuss the Hermite-Birkhoff interpolation and the determination of RBF-CFD weights, as presented in the references40,41,42,43.

Lagrange form of conditionally positive definite RBF interpolation

Let \(K: \mathbb {R}^d\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be a conditionally positive definite RBF of order m. This means that it is positive definite with respect to polynomials of degree \(m-1\) in \(\mathbb {R}^d\), which we denote as \(\Pi _{m-1}(\mathbb {R}^d)\). Suppose that \(\mathbb {X}=\{\varvec{x}_1,\varvec{x}_2,...,\varvec{x}_N\}\) is a set of scattered points in an open bounded region \(\Omega\) in \(\mathbb {R}^d\). Suppose that \(\{u(\varvec{x}_1),u(\varvec{x}_2),...,u(\varvec{x}_N)\}\) are the values of the function u that correspond to the points \(\mathbb {X}\). Then the interpolant of u on the points \(\mathbb {X}\) can be written as

where \(\{p_j\}_{j=1}^Q\) are the basis of \(\Pi _{m-1}(\mathbb {R}^d)\) with \(Q=(m-1+d)!/(d!(m-1)!)\). Now, the unknown coefficients \(\varvec{\alpha }=\{\alpha _1,\alpha _2,...,\alpha _N\}\) and \(\varvec{\beta }=\{\beta _1,\beta _2,...,\beta _Q\}\) are identified by imposing the interpolation conditions:

combined with the side conditions:

In the matrix form, we have:

where

Let \(\mathbb {X}\) be a \(\Pi _{m-1}(\mathbb {R}^d)\)-unisolvent set. Then, the system (2.2) has a unique solution49. To obtain the Lagrange form of the interpolant (2.1), we can rewrite (2.1) using (2.2) as follows:

where

Let \(\mathbb {L}\) be a linear operator. By applying \(\mathbb {L}\) to both sides of (2.4), we obtain an approximation of \(\mathbb {L}u(\varvec{x}_0)\) at a specific test point \(\varvec{x}_0\) as

The Hermite-Birkhoff interpolation

Let \(\varvec{\eta } = \{\eta _1, \eta _2, \dots , \eta _N \} \subset \mathbb {N}_0^d\) be a set of multi-indices such that \(|\eta _i| \le n_0\), where \(n_0\) is a predetermined integer in \(\mathbb {N}_0\). The Hermite-Birkhoff interpolation of a function \(u\) can then be expressed as50:

The subscript 2 on a differential operator \(\mathbb {D}^{\eta _i}\) indicates that the operator is applied to the kernel K with respect to its second argument. The unknown coefficients in the expression above can be determined by the following conditions:

It should be noted that the conditions must be distinct, at least at the points or with respect to the differential operators. The matrix formulation of this interpolation system can be expressed as:

where

The subscripts 1 and 2 denote that the differential operator is applied to the kernel K with respect to its first and second arguments, respectively. Similar to (2.1), the interpolant (2.7) can be enhanced by adding polynomial terms as follows:

with the conditions in (2.8) in conjunction with the following conditions

Therefore, the matrix system would be as follows:

where

It can be proven that for an m-order conditionally positive definite function K and linearly independent operators \(\mathbb {D}^{\eta _i}\) for \(i=1,2,...,N\), if \(\mathbb {D}^{\eta _i} p = 0\) for all \(i=1,2,\ldots ,N\) and \(p \in \Pi _{m-1}(\mathbb {R}^d)\), implies that \(p = 0\), then the system (2.12) has a unique solution39.

Let \(\eta\) be a multi-index such that \(|\eta |\le n_0\). To approximate \(\mathbb {D}^\eta u(\varvec{x}_0)\) using the values of \(\mathbb {D}^{\eta _i} u(\varvec{x}_i)\) for \(i = 1, 2, \dots , N\), we can write:

To obtain the coefficients \(\gamma _1, \gamma _2, \dots , \gamma _N\), we operate \(\mathbb {D}^\eta\) on both sides of (2.11), and we have:

and then, utilizing (2.12), we can get:

where

Determination of RBF-CFD weights

Let’s consider the partial differential equation \(\mathbb {L}u = g\) defined on a domain \(\Omega\), where \(\mathbb {L}\) is a linear operator with constant coefficients and g is a given function. Let \(\mathbb {X}=\{\varvec{x}_1,\varvec{x}_2,...,\varvec{x}_N\}\) be a set of discrete trial points within the domain \(\Omega\) and \(\mathbb {X}_0=\{\varvec{x}_1, \varvec{x}_2, \ldots , \varvec{x}_n\}\) be a stencil for a specific test point \(\varvec{x}_0\). Let \(\mathbb {I}=\{1,2,...,n\}\), \(\bar{\mathbb {I}}\) be an index set of size \(\bar{n}\) such that \(\bar{\mathbb {I}}\subseteq \mathbb {I}\), and \(\bar{\mathbb {X}}_0=\{\varvec{x}_j:j\in \bar{\mathbb {I}}\}\subseteq \mathbb {X}_0\). The RBF-CFD approximation of \(\mathbb {L}u(\varvec{x}_0)\) can be expressed as follows:

where \(\varrho _i\) and \(\bar{\varrho }_i\) are the Lagrange functions on sets \(\mathbb {X}_0\) and \(\bar{\mathbb {X}}_0\). The Lagrange functions are obtained using the following system

where \(\varvec{B}_{K,\varvec{\eta }}=\left( \begin{array}{ll} \varvec{B} & \varvec{B}_{\mathbb {L}}^1 \\ \varvec{B}_{\mathbb {L}}^2 & \varvec{B}_{\mathbb {L}\mathbb {L}}\\ \end{array}\right)\) and \(\varvec{P}_{\varvec{\eta }}= \left( \begin{array}{l} \varvec{P} \\ \varvec{P}_{\mathbb {L}}\\ \end{array}\right)\) such that

and the right hand side vectors are

To construct a discrete version of \(\mathbb {L}u\) using the RBF-CFD method, we consider a set of test points \(\mathbb {Y} = \{y_1, y_2, ..., y_m\}\), which may differ from the trial set \(\mathbb {X}\) within the domain \(\Omega\). For each test point \(y_k\), we create its corresponding stencil \(\mathbb {X}_k \subset \mathbb {X}\) and replace \(\varvec{x}_0\) in the previous formulation with \(y_k\) to obtain the weight vectors \(\varvec{\gamma }_k\) and \(\bar{\varvec{\gamma }}_k\) by solving the local system (2.17) associated with the stencil \(\mathbb {X}_k\). These vectors contain the non-zero coefficients needed to approximate \(\mathbb {L}u(y_k)\) using the function values \(u(\textbf{x}_i)\) and the \(\mathbb {L}u(\textbf{x}_i)\) values at the stencil points. To assemble the global matrix operators, we map these local weight vectors into rows corresponding to \(y_k\). Specifically, the k-th row of the \(m \times N\) matrix \(\mathbb {M}^{(\mathbb {L})}\) is constructed by placing the n elements of \(\varvec{\gamma }_k\) into the columns corresponding to their respective indices in the global trial set \(\mathbb {X}\), and setting all other \(N-n\) entries in that row to zero. A similar procedure is followed for the matrix \(\widehat{\mathbb {M}}^{({\mathbb {L}})}\) using \(\bar{\varvec{\gamma }}_k\).

Therefore, by expanding both \(\varvec{\gamma }_k\) and \(\bar{\varvec{\gamma }}_k\) by adding zeros and organizing them into the rows of the global matrices \(\mathbb {M}^{(\mathbb {L})}\) and \(\hat{\mathbb {M}}^{({\mathbb {L}})}\), we derive the RBF-CFD approximation:

where \(\mathbb {L} \, \varvec{u}_e=\left( \mathbb {L} u(x_1), \mathbb {L} u(x_2),...,\mathbb {L} u(x_N) \right) ^T=\left( g(x_1), g(x_2),...,g(x_N) \right) ^T\) and \(\varvec{u}_e\) is defined as before.

In the RBF-based methods, the selection of the RBF shape parameter is of significant importance, as its proper choice crucially impacts the method’s effectiveness and accuracy51,52. This sensitivity can pose a major challenge in practical implementation. In this work, we utilize the polyharmonic radial kernel in our local approximation. This choice is advantageous because polyharmonic kernels are generally parameter-free, meaning they yield efficient interpolation results for scattered data without the need to select or tune a shape parameter53. This strategy eliminates the stability and accuracy complexities associated with shape parameter optimization.

Discrete setting: application of RBF-CFD weights and strang splitting method

Let the set \(\mathbb {X}=\{ \varvec{x}_k \mid k=1, 2, \ldots , N \}\) represent a set of scattered points within the domain \(\Omega\). For a fixed point \(\varvec{x}\in \Omega\), we have:

where

From (3.1), we derive:

As a result, we can express it as:

where

Thus, the approach for solving (1.1)-(1.3) can be expressed as follows:

with the following initialization:

where \(\mathbb {A}^{(\Delta )} := \mathbb {I} - \mathbb {M}^{(\Delta )}\).

We now apply the Strang splitting method to (3.4). For a PDE of the form \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} = (A + B) u\), the Strang splitting method advances the solution from \(u^n\) to \(u^{n+1}\) over a time step \(\Delta t\) as follows44,54:

where \(A^{\Delta t/2}\) and \(B^{\Delta t}\) are the evolution operators for \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} = A u\) and \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} = B u\), respectively.

For solving (3.4)-(3.5), the time interval \([0, t_F]\) is divided into \(N_t\) subintervals of step size \(\delta t\), where \(t_n = n\delta t\). The Strang splitting procedure for (3.4) consists of the following three steps:

-

1.

First step: Solve the following equation for \(\varvec{v}(t)\) over the time interval \((t_n, t_{n+1}]\):

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \dfrac{d}{dt}\varvec{v}(t) = -\dfrac{1}{2\varepsilon ^2}\, F'(\varvec{v}(t)), & t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}], \\[2ex] \varvec{v}(t_n) = \varvec{u}_{spl}(t_n). \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(3.6) -

2.

Second step: Solve the following equation for \(\varvec{w}(t)\) over the same time interval:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \dfrac{d}{dt}\varvec{w}(t) = (\mathbb {A}^{(\Delta )})^{-1} \mathbb {M}^{(\Delta )}\, \varvec{w}(t), & t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}], \\[2ex] \varvec{w}(t_n) = \varvec{v}(t_{n+1}). \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(3.7) -

3.

Third step: Solve the following equation for \(\varvec{u}(t)\):

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \dfrac{d}{dt}\varvec{u}(t) = -\dfrac{1}{2\varepsilon ^2}\, F'(\varvec{u}(t)), & t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}], \\[2ex] \varvec{u}(t_n) = \varvec{w}(t_{n+1}), \\[2ex] \varvec{u}_{spl}(t_{n+1}):= \varvec{u}(t_{n+1}). \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(3.8)

Here, \(n=0:N_t-1\), and \(\varvec{u}_{spl}(t_{n+1})= \varvec{u}(t_{n+1})\) represents the solution at time \(t_{n+1}\).

To solve equation (3.7), we employ a finite difference method based on the \(\theta\)-rule55. Further, we leverage the known solutions of equations (3.6) and (3.8) to develop a thre-step algorithm:

-

1.

First step: In this step, the updated value of \(\varvec{u}^{n*}\) is calculated using the previous value \(\varvec{u}^n\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varvec{u}^{n*} = \dfrac{\varvec{u}^{n}}{\sqrt{\exp \left( -\dfrac{\delta t}{\varepsilon ^2}\right) + (\varvec{u}^{n})^2 \left( 1 - \exp \left( -\dfrac{\delta t}{\varepsilon ^2}\right) \right) }}. \end{aligned}$$ -

2.

Second step: At this stage, we solve the following system for \(\varvec{u}^{n**}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varvec{u}^{n**} - \theta \, \delta t \, (\mathbb {A}^{(\Delta )})^{-1} \mathbb {M}^{(\Delta )} \varvec{u}^{n**} = \varvec{u}^{n*} + (1-\theta ) \, \delta t \, (\mathbb {A}^{(\Delta )})^{-1} \mathbb {M}^{(\Delta )} \varvec{u}^{n*}. \end{aligned}$$ -

3.

Third step: Finally, in this step, we compute \(\varvec{u}^{n+1}\) using the previous value \(\varvec{u}^{n**}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varvec{u}^{n+1} = \dfrac{\varvec{u}^{n**}}{\sqrt{\exp \left( -\dfrac{\delta t}{\varepsilon ^2}\right) + (\varvec{u}^{n**})^2 \left( 1 - \exp \left( -\dfrac{\delta t}{\varepsilon ^2}\right) \right) }}, \end{aligned}$$

where \(n=0:N_t-1\); \(\varvec{u}^n\) represents the approximate value of \(\varvec{u}(t_n)\), and \(\varvec{u}^{n*}\) and \(\varvec{u}^{n**}\) are the intermediate solutions.

For the second step, singular value decomposition (SVD) can be considered for solving the system, which is described as follows:

We rewrite it in the matrix form:

where

and

To solve for \(\varvec{u}^{n**}\) using SVD, we proceed as follows:

-

1.

First step: Calculate the SVD of \(\mathbb {W}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb {W} = \mathbb {U} \, \mathbb {S} \, \mathbb {V}^T, \end{aligned}$$where

-

\(\mathbb {U}\) and \(\mathbb {V}\) denote orthogonal matrices.

-

\(\mathbb {S}\) is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values.

-

-

2.

Second step: Compute the inverse of \(\mathbb {S}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb {S}^{-1} = \text {diag} \left( \frac{1}{\sigma _i} \right) , \end{aligned}$$where \(\sigma _i\) are the nonzero singular values of \(\mathbb {S}\).

-

3.

Third step: Compute the pseudoinverse of \(\mathbb {W}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb {W}^{-1} = \mathbb {V}\, \mathbb {S}^{-1} \, \mathbb {U}^T. \end{aligned}$$ -

4.

Fourth step: Solve for \(\varvec{u}^{n**}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varvec{u}^{n**} = \mathbb {W}^{-1} \, \varvec{b}. \end{aligned}$$

Test examples

In this section, we present several numerical experiments to evaluate the performance, accuracy, and stability of the proposed method when applied to the two-dimensional Allen-Cahn equation. We examine the convergence behavior with respect to spatial and temporal discretization parameters and investigate the capability of the method to preserve qualitative properties of the solution, such as energy decay over time. In the numerical examples, we employed polyharmonic splines of degree 5, augmented by polynomials of degree 5, collectively denoted as \(PHS5+P5\).

Convergence and accuracy tests

Example 1

For \(\varepsilon =1\) and \(\Omega =[0,1]^2\), the 2D AC equation (1.1) is considered with the following initial condition:

together with Dirichlet boundary conditions. The exact solution to this equation is represented as follows.

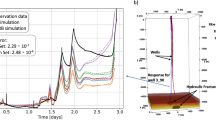

In Fig. 1, we present the root mean square error (RMSE) and maximum absolute error (MaxError) for \(t_F = 1\) with \(\delta t = 0.0005\) as functions of \(h\) on the domain \(\Omega\), using \(\text {PHS5+P5}\). The error decreases as \(h\) decreases, which confirms the accuracy of the proposed framework. Table 2 presents the MaxError and RMSE for different values of \(\delta t\) and h at the final time \(t_F=1\). The results show that as \(\delta t\) decreases, the errors decrease as well, indicating improved accuracy with smaller time step sizes.

The MaxError and RMSE values as a function of \(h\) at \(t_F = 1\) with \(\delta t = 0.0005\) in Example 1.

Example 2

For \(\varepsilon =1\) and \(\Omega = [0,1]^2\), the 2D AC equation (1.1) is considered with the following initial condition:

together with Dirichlet boundary conditions. The exact solution to this equation is:

Figure 2 illustrates the MaxError and RMSE for \(t_F = 1\) with \(\delta t = 0.0005\) as functions of \(h\), using \(\text {PHS5+P5}\). The results show that the error decreases as \(h\) is refined, validating the accuracy of the proposed method. Table 3 displays the MaxError and RMSE at the final time \(t_F=1\) for different values of \(\delta t\) and \(h\). Table 4 shows the MaxError, RMSE, and temporal convergence rate at the final time \(t_F=5\) for various values of \(\delta t\) and \(h=0.08\).

The MaxError and RMSE values as a function of \(h\) for \(t_F = 1\) with \(\delta t = 0.0005\) in Example 2.

Example 3

For \(\varepsilon >0\) and \(\Omega =[0,1]^2\), the 2D AC equation (1.1) is considered with the following initial condition:

together with Dirichlet boundary conditions. The exact solution to this equation is represented as follows

We first set \(\varepsilon = 1\). Table 5 presents the \(L^2\)-norm error and CPU time at final times \(t_F = 1\) and \(t_F = 2\) for different values of \(h\). The results are compared for different time step sizes \(\delta t = 4h^2\). The table also includes the \(L^2\)-norm error values from the reference56 and the RBF-FD method for comparison. Table 6 presents the \(L^2\)-norm error and CPU time at final time \(t_F = 1\) for different values of \(\varepsilon = 0.2, 0.3, 0.6\). The table shows how the \(L^2\)-norm error and computational time vary with different values of \(h\) and the corresponding time step sizes \(\delta t = 4h^2\).

Figures 1 and 2 show that the error decreases when the spatial step size \(h\) is refined. From the slope of the error curves, it can be seen that the method reaches spatial convergence order 2 or higher. It confirms the effectiveness of the utilized spatial discretization. Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the temporal integration convergence rates (Rate) for RMSE. It can be observed that the temporal convergence rate is around 1. This linear convergence over time can be observed in different examples. It shows that the time-stepping scheme keeps stable first-order accuracy even for the nonlinear dynamics of the Allen-Cahn equation. Table 5 compares the proposed approach with the RBF-FD method and also the results reported in56. At \(t_F = 1\) with \(h=1/32\), our method give an \(L^2\)-norm error of \(1.8898 \times 10^{-4}\), which is lower than the \(3.9658 \times 10^{-4}\) from RBF-FD and the \(1.24 \times 10^{-3}\) reported in56. Although CPU times are almost similar, this comparisons show that the proposed method achieves better accuracy. Table 6 demonstrates the robustness of the method for various values of the parameter \(\varepsilon\). As mentioned in equation (1.1), \(\varepsilon\) controls the width of the interface between phases. When \(\varepsilon\) is decreased, the gradients become sharper and the interface thinner, which naturally increases the stiffness of the problem. This makes the numerical approximation more challenging. The reported results in Table 6 show this physical behavior of the problem, as \(\varepsilon\) decreases from 0.6 to 0.2, the errors increase because of the steep transitions in the solution profile. Even for small values of \(\varepsilon\), the method stays stable and gives suitable results, showing its ability to handle the sharp interface dynamics of the Allen-Cahn equation.

Dumbbell shaped

Example 4

For \(\varepsilon >0\) and \(\Omega = [-1,1]^2\), we consider the 2D AC equation (1.1) with the initial condition:

Snapshots at different times with \(h=0.06\) and \(\delta t=0.0005\) in Example 4.

Energy as a function of time for \(h=0.06\) and \(\delta t=0.0005\) in Example 4.

We take \(\varepsilon =0.05\). The initial condition describes a dumbbell-shaped interface that is divided into three distinct regions. The evolution of the solution over time is shown in Fig. 3, with snapshots taken at different times for \(h = 0.06\) and \(\delta t = 0.0005\). Figure 4 illustrates the steady decrease in total energy over time, indicating dissipation or energy loss.

Merging of bubbles

Example 5

For \(\varepsilon >0\) and \(\Omega = [-1,1]^2\), we consider the 2D AC equation (1.1) with the initial condition:

Snapshots at different times with \(h=0.06\) and \(\delta t=0.0006\) in Example 5.

Energy as a function of time with \(h=0.06\) and \(\delta t=0.0006\) in Example 5.

We take \(\varepsilon =0.06\). Simulations are then carried out to observe the evolution of the solution over time. Figure 5 illustrates the results of these simulations, where snapshots of bubble dynamics are shown at different times. In this simulation, a time step size of \(\delta t = 0.0006\), and a spatial step size of \(h = 0.06\) are used. As illustrated in the snapshots, the bubbles merge and undergo shape changes over time. Figure 6 shows the steady decrease in total energy over time, indicating dissipation or energy loss.

Star-like shaped

Example 6

For \(\Omega = [0,1]^2\), the 2D AC equation (1.1) is considered with the following initial condition:

Snapshots at different times with \(h=0.03\) and \(\delta t=0.0002\) in Example 6.

Energy as a function of time with \(h=0.03\) and \(\delta t=0.0002\) in Example 6.

We take \(\varepsilon = 0.05\) in this example. The evolution of the solution is displayed in Fig. 7, showing snapshots of the solution at different times. The results demonstrate the dynamics of the solution over time with \(h=0.03\) and \(\delta t=0.0002\). Figure 8 shows the steady decrease in total energy over time, indicating dissipation or energy loss.

Double axe shaped

Example 7

For \(\Omega = [-2,2]^2\), the 2D AC equation (1.1) is considered with the following initial condition:

where \(d(x_1,x_2)=\max \{-d_1(x_1,x_2),d_2(x_1,x_2),-d_3(x_1,x_2)\}\)

Snapshots at different times with \(h=0.1\) and \(\delta t=0.001\) in Example 7.

Energy as a function of time with \(h=0.1\) and \(\delta t=0.001\) in Example 7.

In this example, we set \(\varepsilon = 0.15\). Figure 9 displays the evolution of the solution, showing snapshots at different times. The results demonstrate the dynamics of the solution over time with \(h=0.1\) and \(\delta t=0.001\). Figure 10 depicts a consistent decrease in total energy over time, indicating dissipation or energy loss.

Conclusion

This study presents a robust and accurate local meshless method for solving the two-dimensional Allen-Cahn equation, employing the RBF-CFD approach in combination with the Strang splitting technique. The Allen-Cahn equation is critical for modeling phase transitions and interface dynamics, and its numerical solution is essential for applications spanning materials science, fluid dynamics, and biology. By combining the RBF-CFD method with the Strang splitting technique, we have significantly enhanced both the accuracy and computational efficiency of the solution process. The proposed method achieves high-order spatial accuracy through the use of the Hermite RBF interpolation technique, which efficiently approximates the model operators on local stencils. This approach has proven to be especially effective in addressing nonlinear equations and complex systems, ensuring that key physical properties, such as energy decay, are preserved over time. Furthermore, the Strang splitting technique contributes to improved efficiency by decomposing the equation into simpler components, all while maintaining high accuracy. Extensive numerical simulations have been conducted to assess the performance of the method, evaluating its accuracy, stability, and convergence across different configurations. The results confirm the method’s capability to preserve crucial qualitative features, making it a powerful tool for solving complex problems related to phase transitions and pattern formation in various physical systems. In conclusion, the demonstrated effectiveness and flexibility of this approach point to its significant potential for broad practical applications in scientific computing and engineering.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allen, S. M. & Cahn, J. W. A microscopic theory for antiphase boundary motion and its application to antiphase domain coarsening. Acta Metall. 27(6), 1085–1095 (1979).

Allen, S. M. & Cahn, J. W. Ground state structures in ordered binary alloys with second neighbor interactions. Acta Metall. 20(3), 423–433 (1972).

Cahn, J. W. & Novick-Cohen, A. Evolution equations for phase separation and ordering in binary alloys. J. Stat. Phys. 76(3), 877–909 (1994).

Tourret, D., Liu, H. & LLorca, J.,. Phase-field modeling of microstructure evolution: Recent applications, perspectives and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 123, 100810 (2022).

Bray, A. J. Theory of phase-ordering kinetics. Adv. Phys. 43(3), 357–459 (1994).

Poochinapan, K. & Wongsaijai, B. Numerical analysis for solving Allen-Cahn equation in 1D and 2D based on higher-order compact structure-preserving difference scheme. Appl. Math. Comput. 434, 127374 (2022).

Lee, C., Choi, Y. & Kim, J. An explicit stable finite difference method for the Allen-Cahn equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 182, 87–99 (2022).

Kim, Y., Ryu, G. & Choi, Y. Fast and accurate numerical solution of Allen-Cahn equation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 5263989 (2021).

Lee, D. The numerical solutions for the energy-dissipative and mass-conservative Allen-Cahn equation. Comput. Math. Appl. 80(1), 263–284 (2020).

Lan, R., Li, J., Cai, Y. & Ju, L. Operator splitting based structure-preserving numerical schemes for the mass-conserving convective Allen-Cahn equation. J. Comput. Phys. 472, 111695 (2023).

Lee, H. G., Shin, J. & Lee, J. Y. A high-order and unconditionally energy stable scheme for the conservative Allen-Cahn equation with a nonlocal Lagrange multiplier. J. Sci. Comput. 90, 51 (2022).

Xu, M. et al. Symmetry-breaking dynamics of a flexible hub-beam system rotating around an eccentric axis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 222, 111757 (2025).

Hu, W. et al. Coupling dynamic problem of a completely free weightless thick plate in geostationary orbit. Appl. Math. Model. 137, 115628 (2025).

Xi, X., Hu, W., Yan, J., Wu, F. & Zhang, C. Structure-preserving analysis on hub-cracked beam with hollow tapered cross-section. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 240, 113374 (2025).

Hu, W., Han, Z., Wu, F., Yan, J. & Deng, Z. Coupling dynamic behaviors of flexible thin-walled tapered hub-beam with a tip mass. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 13, 447 (2025).

Zhu, H., Han, Z. & Hu, W. Generalized Multi-Symplectic Analysis for Lateral Vibration of Vehicle-Bridge System Subjected to Wind Excitation. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 13, 460 (2025).

Hu, W., Xi, X., Song, Z., Zhang, C. & Deng, Z. Coupling dynamic behaviors of axially moving cracked cantilevered beam subjected to transverse harmonic load. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 204, 110757 (2023).

Kormann, K., Nazarov, M. & Wen, J. A structure-preserving finite element framework for the Vlasov-Maxwell system. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 446, 118290 (2025).

Mohammadi, V., Mirzaei, D. & Dehghan, M. Numerical simulation and error estimation of the time-dependent Allen-Cahn equation on surfaces with radial basis functions. J. Sci. Comput. 79(1), 493–516 (2019).

Emamjomeh, M., Nabati, M. & Dinmohammadi, A. Numerical study of two operator splitting localized radial basis function method for Allen-Cahn problem. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 163, 126–137 (2024).

Kim, J. & Hwang, Y. Maximum Principle-Preserving Computational Algorithm for the 3D High-Order Allen-Cahn Equation. Mathematics 13(7), 1085 (2025).

Hwang, Y., Kwak, S., Kim, H. & Kim, J. An explicit numerical method for the conservative Allen-Cahn equation on a cubic surface. AIMS Math. 9(12), 34447–34465 (2024).

Zhang, H., Yan, J., Qian, X. & Song, S. Numerical analysis and applications of explicit high order maximum principle preserving integrating factor Runge-Kutta schemes for Allen-Cahn equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 161, 372–390 (2021).

Wang, Y., Xiao, X. & Feng, X. Numerical simulation for the conserved Allen-Cahn phase field model of two-phase incompressible flows by an efficient dimension splitting method. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 131, 107874 (2024).

Zhang, H., Qian, X. & Song, S. Third-order accurate, large time-stepping and maximum-principle-preserving schemes for the Allen-Cahn equation. Num. Algorithms 95(3), 1213–1250 (2024).

Hao, W., Lee, S., Xu, X. & Xu, Z. Stability and robustness of time-discretization schemes for the Allen-Cahn equation via bifurcation and perturbation analysis. J. Comput. Phys. 521, 113565 (2025).

Hou, Y., Li, J., Qiao, Y. & Feng, X. An efficient Crank-Nicolson scheme with preservation of the maximum bound principle for the high-dimensional Allen-Cahn equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 465, 116586 (2025).

Hou, D., Zhang, T. & Zhu, H. A linear second order unconditionally maximum bound principle-preserving scheme for the Allen-Cahn equation with general mobility. Appl. Numer. Math. 207, 222–243 (2025).

Abbasbandy, S., Shivanian, E. & AL-Jizani, K. H.,. On the analysis of a kind of nonlinear Sobolev equation through locally applied pseudo?spectral meshfree radial point interpolation. Num. Methods Partial Diff. Equ. 37(1), 462–478 (2021).

Shivanian, E. & Abbasbandy, S. Pseudospectral meshless radial point interpolation for generalized biharmonic equation in the presence of Cahn-Hilliard conditions. Comput. Appl. Math. 39, 148 (2020).

Mir, R. & Mirzaei, D. The D-RBF-PU method for solving surface PDEs. J. Comput. Phys. 479, 112001 (2023).

Mohammadi, V., Dehghan, M. & Mesgarani, H. The localized RBF interpolation with its modifications for solving the incompressible two-phase fluid flows: A conservative Allen–Cahn–Navier–Stokes system. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 168, 105908 (2024).

Chen, C. L., Wu, C. H. & Chen, C. O. K. A Meshless Method of Radial Basis Function-Finite Difference Approach to 3-Dimensional Numerical Simulation on Selective Laser Melting Process. Appl. Sci. 14(15), 6850 (2024).

Safari, F. & Duan, Y. Inverse Cauchy problem in the framework of an RBF-based meshless technique and trigonometric basis functions. Eng. Comput. 40, 4067–4080 (2024).

Ahmad, M., Khan, M. N. & Ahmad, I. Local meshless methods for elliptic PDEs with multipoint boundary conditions: investigating efficiency and accuracy of various RBFs. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 234, 2525–2542 (2024).

Fardi, M. & Azarnavid, B. A study on the numerical solution of the Sobolev equation with a Burgers-type nonlinearity on two-dimensional irregular domains using the local RBF partition of unity method. Comput. Appl. Math. 44, 17 (2025).

Azarnavid, B., Fardi, M. & Mohammadi, S. Numerical simulation of coupled Klein–Gordon–Schrödinger equations: RBF partition of unity. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 163, 562–575 (2024).

Yao, G., Sarler, B. & Chen, C. S. A comparison of three explicit local meshless methods using radial basis functions. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 35(3), 600–609 (2011).

Wendland, H. Scattered data approximation (Vol. 17). Cambridge University Press (2004).

Wright, G. B. & Fornberg, B. Scattered node compact finite difference-type formulas generated from radial basis functions. J. Comput. Phys. 212(1), 99–123 (2006).

Ilati, M. A local radial basis function-compact finite difference method for Sobolev equation arising from fluid dynamics. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 169, 106020 (2024).

Lehto, E., Shankar, V. & Wright, G. B. A radial basis function (RBF) compact finite difference (FD) scheme for reaction-diffusion equations on surfaces. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 39(5), A2129–A2151 (2017).

Arefian, S. & Mirzaei, D. A compact radial basis function partition of unity method. Comput. Math. Appl. 127, 1–11 (2022).

Strang, G. On the construction and comparison of difference schemes. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 5(3), 506–517 (1968).

Hundsdorfer, W., & Verwer, J. G. Numerical solution of time-dependent advection-diffusion-reaction equations (Vol. 33). Springer Science & Business Media (2013).

Li, D., Quan, C., & Xu, J. Stability and convergence of Strang splitting. Part I: scalar Allen-Cahn equation. J. Comput. Phys. 458, 111087 (2022).

Blanes, S., Casas, F. & Murua, A. Splitting methods for differential equations. Acta Numer. 33, 1–161 (2024).

Bertoli, G. & Vilmart, G. Strang splitting method for semilinear parabolic problems with inhomogeneous boundary conditions: a correction based on the flow of the nonlinearity. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 42(3), A1913–A1934 (2020).

Wendland, H. Piecewise polynomial, positive definite and compactly supported radial functions of minimal degree. Adv. Comput. Math. 4, 389–396 (1995).

Zongmin, W. Hermite-Birkhoff interpolation of scattered data by radial basis functions. Approx. Theory Appl. 8(2), 1–10 (1992).

Zhang, X., Song, K. Z., Lu, M. W. & Liu, X. Meshless methods based on collocation with radial basis functions. Comput. Mech. 26, 333–343 (2000).

N., Mai-Duy, & Tran-Cong, T.,. Mesh-free radial basis function network methods with domain decomposition for approximation of functions and numerical solution of Poisson’s equations. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elements 26(2), 133–156 (2002).

Iske, A. On the approximation order and numerical stability of local Lagrange interpolation by polyharmonic splines. In Modern Developments in Multivariate Approximation: 5th International Conference, Witten-Bommerholz (Germany), 153-165. (2003)

He, D., Pan, K. & Hu, H. A spatial fourth-order maximum principle preserving operator splitting scheme for the multi-dimensional fractional Allen-Cahn equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 151, 44–63 (2020).

LeVeque, R. J. Finite difference methods for ordinary and partial differential equations: steady-state and time-dependent problems. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. (2007).

Li, J., Zeng, J. & Li, R. An adaptive discontinuous finite volume element method for the Allen-Cahn equation. Adv. Comput. Math. 49(4), 55 (2023).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A. and H.E. developed the theoretical framework and proposed the core methodology. M.F. conducted the numerical simulations, analyzed the results, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fardi, M., Azarnavid, B. & Emami, H. An innovative meshless approach for solving 2D Allen-Cahn equations using the RBF-compact finite difference method. Sci Rep 16, 6459 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35569-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35569-4