Abstract

Biallelic loss-of-function variants of Seizure Threshold 2 (SZT2) cause neurodevelopmental diseases with developmental delay, epilepsy, and macrocephaly. SZT2 forms the KICSTOR complex, which represses the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) amino acid-sensitive pathway. SZT2 dysfunction is thought to cause abnormal activation of the mTOR pathway, underlying the pathogenesis of SZT2-related diseases. We previously reported constitutive activation of mTORC1 in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from patients with SZT2-related disease. However, the impact of SZT2 dysfunction on human brain development remains unclear. In this study, we examined the effects of SZT2 dysfunction on brain development using human brain organoids. We generated pluripotent stem cell-derived brain organoids and found a significantly greater number of outer radial glial cells (oRGCs) in the subventricular zone-like layer (SVZ) of SZT2 mutant (MT) brain organoids compared to control (WT) brain organoids. The number of upper-layer neurons, which generally originate from oRGCs, was also significantly greater in SZT2 MT brain organoids. Mechanistically, SZT2 MT brain organoids showed higher mTORC1 activity in the SVZ, where neural stem/progenitor cells amplify for cortical expansion in response to mTORC1 activity. Our data suggest that SZT2 dysfunction may cause macrocephaly through dysregulation of mTORC1 in early neural development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seizure threshold 2 (SZT2) is located on chromosome 1p34.2 and contains 71 exons, and is mainly expressed in the parietal lobe, frontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and dorsal root ganglia1. Biallelic mutations in SZT2 were first reported in 2013, with affected individuals presenting with intractable epilepsy and abnormal corpus callosum morphology2. Since then, it has become known that macrocephaly, intractable epilepsy, and severe developmental delay are the core manifestations of SZT2-related disease, or developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 18 (DEE18; OMIM #615476)2,3,4. In 2017, SZT2 was found to be one of the component proteins of the KICSTOR complex, and it regulates mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity by recruiting mTORC1 to lysosomes in an amino acid-sensitive manner5,6. Normally, mTORC1 activity is suppressed under amino acid deficiency. However, dysfunction of SZT2 causes constitutive activation of mTORC1, and mTORC1 activation is associated with cell proliferation, the proliferation of neural stem cells, and the regulation of neuronal differentiation7. Abnormalities in mTOR activity are reported to lead to various disorders, including tumors, macrocephaly, epilepsy, and developmental delays among other neurological diseases8,9.

In 2017, Li et al., demonstrated that PTEN dysfunction leads to the expansion of the ventricular zone-like layer (VZ) and subventricular zone-like layer (SVZ), and the formation of folding structures through the activation of mTORC1. This activation promotes the proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells, ultimately resulting in an increase in the number of neurons10. Notably, mTORC1 activity has also been observed in outer radial glial cells (oRGCs)11. oRGCs are more abundant in humans than in mice, and contribute to the expansion of the human brain by differentiating into upper-layer neurons12,13. Therefore, it is critical to use models that replicate human-specific features to better understand the role of mTORC1 in brain development and its impact on neurodevelopmental disorders like macrocephaly. Brain organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are a model which mimics the early stage of neural development in humans and are a suitable system to understand the role of SZT2 in human brain development14,15.

Previously, we reported that loss of SZT2 function leads to hyperactivation of mTORC1 using patient-derived lymphoblastoid cell lines16. Although there have been reports examining mTORC1 activity in SZT2 function in vitro, it is not clear how SZT2 dysfunction affects neurodevelopment in the human brain. Therefore, we examined the effects of SZT2 dysfunction on mTORC1 activity and early brain development using human brain organoids.

Results

Gene editing of iPSCs by CRISPR/Cas9

To examine how SZT2 affects human brain development, we generated brain organoids using human iPSCs. To assess the role of SZT2, we created sgRNA targeting exon 3 of SZT2 (Fig. 1A). Windy, a well-characterized iPSC line, was utilized to generate frameshift mutations using the CRISPR/Cas9 system17,18,19,20. One day after the CRISPR/Cas9 treatment of iPSCs, using fluorescence-activated cell sorting, 180 cells suspected of having mutations were sorted. Ultimately, one iPSC clone was identified with biallelic variants potentially leading to loss-of-function compound heterozygous mutations through genotyping. We confirmed that the CRISPR-edited clone harbored 13 bp and 110 bp deletions at the exon-intron boundary in a compound heterozygous manner by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1B and C). RT-PCR for the CRISPR-edited iPSC clone revealed that the introduced mutations result in in-frame deletions of 84 bp (28 amino acid residues), corresponding to the distal portion of exon 3 (Fig. 1D and E). It was considered that both deletions involving the exon-intron boundary activated a cryptic splicing donor site in exon 3, and created aberrant splicing products. The CRISPR-edited clone grew normally as compared to control iPSCs (Fig. 1F). Considering the possibility of impaired SZT2 function, we used the edited iPSCs as mutants (MT) and performed the following experiments.

The SZT2 mutant iPSCs generated by CRISPR/Cas9 harbor an in-frame deletion in exon 3. (A) Schematic representation of the designed sequence of single guide RNA (sgRNA) adjacent to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) targeting exon 3 of the human SZT2 locus. Sanger sequencing data of control (WT) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is shown. (B) Electrophoretic analysis of PCR products from the CRISPR/Cas9-targeted region of genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from WT and edited SZT2 mutant (MT) iPSCs. The original gel is presented in Figure S1. (C) Sanger sequencing of the PCR products derived from gDNA of SZT2 MT iPSCs. The SZT2 MT iPSCs contain 13 bp and 110 bp deletions at the exon-intron boundary. (D) RT-PCR of total RNA extracted from WT iPSCs and SZT2 MT iPSCs, with or without reverse transcriptase (RT). The arrowhead and arrow indicate the RT-PCR product bands of WT and MT iPSCs, respectively. The original gel is presented in Figure S2. These bands were analyzed by Sanger sequencing, revealing that the sequence from SZT2 MT iPSCs showed an in-frame 84 bp deletion at the distal portion of exon 3. (E) Schematic representation of the SZT2 gene and SZT2 protein, showing that SZT2 MT iPSCs exhibited an 84 bp skipping event in exon 3. Arrows indicate the primer binding sites used for RT-PCR. The dotted box indicates the skipped region of exon 3. (F) Bright-field images of WT iPSCs and SZT2 MT iPSCs. Scale bar, 100 μm.

SZT2 MT organoids have an increased SVZ to VZ ratio

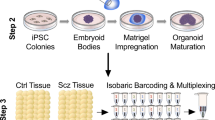

To elucidate the effects of SZT2 on brain development, we created SZT2 MT brain organoids derived from SZT2 MT iPSCs and control (WT) brain organoids from WT iPSCs (Fig. 2A)17. Both of SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids showed embryoid bodies in 6 days, and typical multiple ventricle-like structures in 4 weeks and 8 weeks (Fig. 2B). To confirm that the organoids reproducibly acquired a dorsal forebrain identity, immunostaining demonstrated that both SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids expressed the forebrain marker FOXG1, while lacking expression of the ventral marker NKX2.1 (Fig. 2C). The number of FOXG1+ cells showed no significant difference between SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids across the VZ, SVZ and cortical plate-like layer (CP) (Fig. 2D and E). These data indicate that both SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids have dorsal forebrain identity.

SZT2 mutant brain organoids showing a relative expansion of the SVZ compared to control brain organoids. (A) Schematic illustration of the generation of brain organoids from SZT2 MT and WT iPSCs. (B) Bright-field microscopy images of embryoid bodies at day 6 and brain organoids at 4 and 8 weeks of culture. Scale bars, 200 μm (day 6) and 500 μm (4 and 8 weeks). (C) Immunofluorescence images of WT brain organoids and SZT2 MT brain organoids at 8 weeks of culture using the antibodies against FOXG1 (green, forebrain marker), NKX2.1 (red, ventral marker). Yellow dotted lines delineate the boundaries of ventricular zone-like layer (VZ) and subventricular zone-like layer (SVZ). Scale bar, 200 μm (top), 100 μm (middle and bottom). (D, E) Quantification of the ratios of FOXG1+ cells to DAPI+ nuclei in the VZ (D), SVZ and CP (E). Mean ± SD from two independent experiments (at least four organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 11); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 9). ns, not significant. (F) Immunofluorescence images of WT brain organoids and SZT2 MT brain organoids at 8 weeks of culture. The VZ are marked by dense SOX2 (red) labelling, while the SVZ are indicated by sparse TBR2 (green) labelling adjacent to the VZ. DAPI (blue) labels nuclei. Yellow dotted lines delineate the boundaries of VZ and SVZ. Scale bars, 200 μm. (G) Schematic illustration of the VZ and SVZ, with boundaries defined by the distribution of SOX2+ cells (red) and TBR2+ cells (green). (H, I) Quantification of the surface area (H) and thickness (I) of the VZ and SVZ at 8 weeks of culture. Mean ± SD from four independent experiments (at least three organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 13); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 12). The thickness was calculated by averaging values from three measurements, as shown in the schematic illustration of the VZ and SVZ. * P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Next, we performed immunofluorescence to visualize the VZ, which contains abundant SOX2+ apical radial glial cells (aRGCs), and the SVZ, which consists of sparsely distributed SOX2+ cells corresponding to neural progenitor cells and TBR2+ cells corresponding to intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs; Fig. 2F and G)14,15,17,21,22. To investigate how changes in these regions affect cortical expansion, we compared the area and thickness of the SVZ and VZ in the SZT2 MT brain organoids with those in WT brain organoids. Due to the variations in the size of individual brain organoids, we analyzed the ratio of SVZ to VZ. At 8 weeks, the relative areas of the SVZ compared to the VZ were significantly larger in the SZT2 MT brain organoids than in WT brain organoids (Fig. 2H). The ratio of SVZ to VZ thickness was also significantly greater in the SZT2 MT brain organoids than in WT brain organoids (Fig. 2I). These results suggest that the increased number of cells in the SVZ of SZT2 MT organoids may contribute to the expansion of the SVZ in SZT2 MT brain organoids.

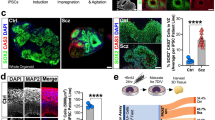

SZT2 MT organoids show an increased number of oRGCs in the SVZ and upper-layer neurons in the CP

To investigate the cell types contributing to the increased SVZ, we analyzed the number of oRGCs. Previous studies have shown that oRGCs can be identified as SOX2+ TBR2− cells and IPCs can be identified as SOX2− TBR2+ in the SVZ23,24. We labelled and quantified the number of SOX2+ TBR2− oRGCs and SOX2− TBR2+ IPCs in the SVZ of brain organoids. Importantly, the number of SOX2+ TBR2− oRGCs was significantly greater in the SVZ of SZT2 MT brain organoids compared to WT brain organoids (Fig. 3A and B). The number of SOX2− TBR2+ IPCs did not differ between the SVZ of SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids (Fig. 3A and C). Since the number of neurons serves as an indicator of cortical expansion10,25, we analyzed the number of neurons in the CP of brain organoids. The number of CTIP2+ lower-layer neurons in the CP was similar between the SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids (Fig. 3D and E). Importantly, the number of SATB2+ upper-layer neurons was significantly greater in the CP of SZT2 MT brain organoids compared to WT brain organoids (Fig. 3D and F). Since upper-layer neurons in the CP are derived from oRGCs in the SVZ12,26,27, our findings support the current hypothesis that an increased number of oRGCs contributes to the expansion of upper-layer neurons in SZT2 MT brain organoids. To evaluate whether mitotic activity was altered, we quantified the number of phosphorylated histone H3 - positive (pH3+) mitotic cells. The proportion of dividing cells lining the apical surface, representing aRGCs divisions28, did not differ significantly between SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids (Fig. 3G and H). In addition, the number of dividing oRGCs and IPCs in the SVZ showed no significant difference between SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids (Fig. 3I and J). These data indicated that the mitotic difference is not the cause of the increased number of oRGCs and upper-layer neurons in SZT2 MT brain organoids.

SZT2 mutant organoids exhibiting an increased proportion of oRGCs in the SVZ and upper-layer neurons in the CP. (A-C) Immunofluorescence images of SOX2+ outer radial glial cells (oRGCs) and TBR2+ intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs) in the SVZ of brain organoids (A). Yellow dotted lines delineate the boundaries of VZ and SVZ. Scale bars, 100 μm. Quantification of the ratios of SOX2+ TBR2− cells to DAPI+ nuclei (B) and SOX2− TBR2+ cells to DAPI+ nuclei (C) in the SVZ. Mean ± SD from three independent experiments (at least three organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 10 (B), 9 (C)); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 11); **P < 0.01; ns, not significant. (D-F) Immunofluorescence images of SATB2+ upper-layer neurons and CTIP2+ lower-layer neurons in the cortical plate-like layer (CP) of WT brain organoids and SZT2 MT brain organoids at 8 weeks (D). Yellow dotted lines delineate the boundaries of SVZ and CP. Scale bars, 200 μm (top) and 100 μm (middle, bottom). Quantification of the ratio of the number of CTIP2+ cells to DAPI+ nuclei (E) and number of SATB2+ cells to DAPI+ nuclei (F) in the CP. Mean ± SD from three independent experiments (at least three organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 12); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 11). *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. (G-J) Immunofluorescence images of pH3+ mitotic cells, SOX2+ cells and TBR2+ cells of WT brain organoids and SZT2 MT brain organoids at 8 weeks. Quantification of the number of pH3⁺ cells to apical surface length (µm) (H), the ratio of the number of pH3+ SOX2+ cells to SOX2+ cells in the SVZ (I) and the number of pH3+ TBR2+ cells to TBR2+ cells in the SVZ (J). Mean ± SD from three independent experiments (at least three organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 11); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 12). ns, not significant.

mTORC1 is activated in the SVZ of SZT2 MT organoids

SZT2 is part of the KICSTOR complex and regulates the mTOR signaling pathway5,6,16. Notably, mTORC1 activity has also been observed in oRGCs11. Given the increased number of oRGCs in SZT2 MT brain organoids, we sought to examine mTORC1 activity in the SVZ. We performed immunolabelling for pS6, a marker of mTORC1 activity. The number of pS6+ cells was significantly greater in the SVZ of SZT2 MT brain organoids than WT brain organoids (Fig. 4A and C). Interestingly, the number of pS6+ cells was significantly increased in the VZ and CP in SZT2 MT brain organoids compared to WT brain organoids (Fig. 4A, B and D). Our results suggest that the CRISPR-mediated mutations in SZT2 dysregulated its function, leading to upregulated mTORC1 activity in SZT2 MT brain organoids. Interestingly, this increase was observed not only in the SVZ but also extended to the VZ and CP of SZT2 MT brain organoids.

mTORC1 activity was significantly elevated in the SVZ of SZT2 mutant brain organoids. (A-D) Immunofluorescence images of pS6+ cells in the SVZ. Yellow dotted lines indicate the boundaries of VZ, SVZ and CP. Scale bars, 200 μm (top), 200 μm (middle), and 100 μm (bottom). Quantification of the ratio of pS6+ cells to DAPI+ nuclei in the VZ (B), SVZ (C), CP (D). Mean ± SD from three independent experiments (at least three organoids per experiment) are plotted: WT brain organoids (n = 10 in the VZ and CP, n = 9 in the SVZ); SZT2 MT brain organoids (n = 9). ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

One of the clinical features of SZT2-related diseases is macrocephaly3,4,29, but the pathomechanism is yet to be elucidated. In this study, we investigated how SZT2 affects brain development in SZT2-related diseases using human brain organoids. SZT2 MT brain organoids showed an increase in oRGCs in the SVZ. oRGCs are particularly abundant in the human brain and are considered as a critical factor contributing to cortical expansion in humans12,30. oRGCs produce upper-layer neurons, which are fundamental to cortical expansion and gyrification in humans27. Consequently, we showed that SATB2+ upper-layer neurons were significantly greater in the CP of SZT2 MT brain organoids, while the number of CTIP2+ lower-layer neurons remained unchanged. Therefore, these data suggest that the increase in oRGCs in the SVZ during brain development may contribute to macrocephaly in SZT2-related diseases.

SZT2 dysfunction has been reported to enhance mTORC1 activity in other cell types3,31. To investigate the mechanism of the increase in oRGCs, we examined mTORC1 activity in SZT2 MT brain organoids. mTORC1 activity, shown by an increase in pS6 signals, was significantly greater in the SVZ of SZT2 MT brain organoids, compared to WT brain organoids. Our study extends previous findings, and shows that SZT2 dysfunction leads to mTORC1 upregulation during early brain development. mTOR is highly expressed in oRGCs in neural stem cells11,32, and a recent study showed that hypoactivity of the mTOR pathway in the SVZ of the developing brain contributed to lissencephaly33. Therefore, it is plausible that mTOR activity in oRGCs is a major determinant of subsequent cortical expansion. We considered that SZT2 dysfunction upregulates mTORC1 activity resulting in an increase of oRGCs in the SVZ, which subsequently induces a significant increase in SATB2+ upper-layer neurons in the CP underlying the cortical expansion. Because no significant difference was observed in the proportion of pH3-positive mitotic stem cells and progenitors between SZT2 MT and WT brain organoids, the increased number of upper-layer neurons in SZT2 MT brain organoids is unlikely to be explained by increased mitotic activity and may instead reflect changes in progenitor fate specification and/or neurogenic differentiation. Therefore, our observations of increased oRGCs in the SVZ and increased upper-layer neurons in the CP may be explained, at least in part, by altered oRGCs dynamics induced by mTORC1 hyperactivation. Moreover, mTORC1 hyperactivation was also present in the CP of SZT2 MT brain organoids. Because neuronal mTORC1 activity is known to regulate synaptogenesis and axonal development34,35,36, such alterations may influence cortical circuit formation. Although our data do not directly assess neural-network function, these observations suggest a potential mechanistic link through which SZT2 dysfunction could contribute to the neural abnormalities underlying epilepsy in SZT2-related diseases. Taken together, when hyperactivity of mTORC1 underlies the pathogenesis of SZT2-related diseases, it is reasonable to consider mTOR inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents.

However, an important limitation of this study is that all organoid experiments were conducted using a single iPSC line, preventing validation across multiple independent lines. Nevertheless, given the known role of SZT2 as a regulator of the mTOR pathway, our findings represent, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of mTORC1 hyperactivation in human brain organoids with SZT2 dysfunction.

SZT2-related diseases have been reported to be associated with callosal dysmorphogenesis, particularly in the formation of a thick corpus callosum3,4,37. During brain development, upper-layer neurons project to the corpus callosum38,39. Therefore, our results suggest that SZT2 dysfunction may enhance the projection of upper-layer neurons to the corpus callosum, which underlies callosal dysmorphogenesis.

SZT2 is localized to the lysosomal membrane and forms the KICSTOR complex consisting of four proteins, which interacts with GATOR1 to regulate mTORC1 activity5,6. However, to date, the functional domains of SZT2, other than the binding site for GATOR1, have not been identified5,16. We have demonstrated that a truncated form of mutant SZT2 lacking 28 amino acid results in enhanced mTORC1 activity and recapitulates SZT2-related diseases. Therefore, it would be interesting to perform a biochemical analysis of the functional domains of SZT2 and elucidate its role in the KICSTOR complex in future studies.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that SZT2 dysfunction upregulates mTORC1 activity in the SVZ and increases the number of oRGCs during brain development, which may underlie the cortical expansion leading to macrocephaly in patients with SZT2-related diseases. Furthermore, these findings may support the future development of therapeutic agents, such as mTOR inhibitors, to target SZT2-related diseases.

Materials and methods

Generation of SZT2 mutant human iPSCs

Gene editing of iPSCs was performed using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. To prepare ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, 3 µL of 100 µM crRNA and 3 µL of 100 µM tracrRNA labeled with Atto550 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Cat#1075928) were mixed with 4 µL of buffer, followed by incubation at 95 °C for 5 min, and then at room temperature (RT) for 30 min to create gRNA. Next, 1 µL of 62 µM Cas9 protein (Alt-R™ S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3, Integrated DNA Technologies, Cat#1081060) was added to the gRNA complex and incubated at RT for 30 min to form the RNP complex. Subsequently, 1 × 106 iPSCs were mixed with 5 µL of the RNP complex and 95 µL of Opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco, Cat#31985062), and were electroporated with Nucleofector® 2b (Lonza, Germany). The cells were immediately seeded into iPSC medium. The next day, cell sorting (FACSAria III, BD Biosciences, USA) was performed, and single cells labeled with atto550 were seeded into 96-well plates. Genotyping of the expanded clones was performed. Since electrophoresis revealed two bands differing from the expected size in a single clone, the bands were separated by gel electrophoresis and extracted with a gel extraction kit (QIAquick® Gel Extraction Kit 50, Qiagen, Cat#28704) and subjected to Sanger sequencing. The oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: The crRNA used for CRISPR editing was TTGGACCTTAGCCCATCTAC (Design ID: Hs.Cas9.SZT2.1.AB; Integrated DNA Technologies). The primers used for genotyping were AGAGAGTGAGAGGAAGAG (forward), TGGGATTGTAGGCATGAG (reverse), and GGCTGGGACCATTTTTCA (reverse).

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from WT and SZT2 MT iPSCs using the RNeasy® plus mini kit (250) (Qiagen, Cat#74136). PCR was then performed with the primers located in SZT2 exons 2 and 5 listed below. After electrophoresis was conducted for 30 min with 3% agarose gel (UltraPure Agarose, Invitrogen, Cat#16500-500), the bands which were photographed by gel imager were excised from the gel. RT-PCR products were extracted using the gel extraction kit, and Sanger sequencing was performed. Subsequently, reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Cat#18091050) to create cDNA. The primers used for the PCR step were CTCAGTCATCTGCACCAA (forward, targeting exon 2) and GGCCACCTTATCCTCAAA (reverse, targeting exon 5).

Culture of human iPSCs

Previously established iPSCs (Windy) were used in the current study17. iPSCs were cultured in StemFit® AK02N (Ajinomoto, Cat#AK02N) which contained 10 µM Y27632 dihydrochloride (Chemscene, Cat#CS-0878) and 0.2 µg/cm2 iMatrix-511 silk (Takara Bio, Cat#892021) on day 0. The next day, the media was replaced to remove Y27632 dihydrochloride. The culture media was changed every 1–3 days, and iPSCs were passaged at 5–7 days. Mycoplasma contamination was tested for using the VenorGeM qOneStep kit (Minerva biolabs, Cat#11-91010) and confirmed to be absent in the passaged iPSCs. The human iPSC line Windy was derived from a human embryonic lung fibroblast cell line (MRC-5) and obtained by Dr. Umezawa. Nagoya City University Institutional Review Board approved the protocol (No.70-20-0008).

Generation of brain organoids from human iPSCs

To create brain organoids, we employed a dual SMAD inhibitor protocol with slight modification40,41,42. For embryoid body (EB) formation, a total of 188,000 iPSCs were seeded into an EZsphere 24-well plate (Iwaki, Cat# 4820-900SP) with ‘EB formation media’ and 50 µM Y27632 dihydrochloride. The media was replaced with ‘induction media’ on days 2 and 4, changing half of the media each time. On day 6, the media was removed, and 200 µL of Matrigel Matrix (Corning, Cat#354234) was added and EB spheroids were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, 1 mL of ‘Organoid 1 media’ was added. On the 10th day, the brain organoids were transferred to poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#P3932-10G)-coated six-well plates. On the 14th day, the media was replaced with ‘Organoid 2 media’. Organoid 2 media was changed every 1–3 days. After 1 month, the organoids were cut into 2–3 pieces with a scalpel under a stereo microscope to prevent cell death in the central positions43. The organoids were cultured for up to 8 weeks. The following reagents were used for the culture of organoids in this study. The ‘EB formation media’ consisted of DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Cat#11330-032) supplemented with 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#10828010), 1 mM MEM Nonessential Amino Acids Solution (Nacalai Tesque, Cat#06344-56), 2 mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#25030081), and 4 ng/mL FGF-244. The ‘induction media’ consisted of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement, 1 mM MEM Nonessential Amino Acids Solution, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 µM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Wako, Cat#137-06862), 100 nM LDN-193,189 (Cayman Chemical, Cat#19396), 10 µM SB-431,542 (Cayman Chemical, Cat#13031), and 2 µM XAV939 (Cayman Chemical, Cat#13596). The ‘organoid 1 media’ consisted of 50% DMEM/F12 and 50% MACS Neuro Medium (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat#130-093-570) supplemented with 1 mM MEM Nonessential Amino Acids Solution, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 400 nM insulin (Nacalai Tesque, Cat#12878-86), 0.5×N-2 MAX Media Supplement (RSD, Cat#AR009), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution, Wako, Cat#168-23191), and 0.5×MACS NeuroBrew-21 w/o vitamin A (Miltenyi, Cat#130-097-263). The ‘organoid 2 media’ consisted of 50% DMEM/F12 and 50% MACS Neuro Medium supplemented with 1 mM MEM non-essential Amino Acids Solution, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 400 nM insulin, 0.5×N-2 MAX Media Supplement, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.5×MACS NeuroBrew-21 (Miltenyi, Cat#130-093-566), and 200 µM L-Ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#A92902-25G).

Immunofluorescence

Organoids were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako, Cat#162-16065) overnight at 4 °C on a rotator. The next day, the paraformaldehyde was aspirated and replaced with 30% sucrose (Wako, Cat#198-13525), then rotated again at 4 °C. The following day, the solution was aspirated, and the tissue was embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek Japan, Cat#4583) and stored at − 80 °C. Sections of 16 μm thickness were cut using a Leica CM3050 cryostat and stored at − 25 °C. The tissue was washed three times with D-PBS(-) (Wako, Cat#045-29795) to remove the O.C.T. compound, and permeabilized by immersion in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#T9284) for 5 min. Afterwards, blocking was performed at RT for one hour using Blocking One Histo (Nacalai Tesque, Cat#06349-64). The tissue was then incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the samples were washed three times with D-PBS(-) (10 min each), followed by incubation with a secondary antibody containing DAPI (Roche, Cat#68732320) for one hour at room temperature. After another wash with D-PBS(-), VECTASHIELD Vibrance Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Cat#H-1700) was applied, and a glass cover slip placed on top. The samples were left at RT for 2–3 h and then stored at − 20 °C. The samples were observed using a confocal microscope (Nikon A1RS+). The primary antibodies used were; anti-SOX2 (Santa Cruz, Cat#sc-365964; 1:400), anti-TBR2 (abcam, Cat#ab275960; 1:400), anti-CTIP2 (abcam, Cat#ab18465; 1:400), anti-SATB2 (Santa Cruz, Cat#sc-81376; 1:400), anti-phospho-S6 (CST, Cat#5364S; 1:400), anti- FOXG1 (abcam, Cat# ab18259; 1:500), anti-TTF-1 (Thyroid Transcription Factor-1; NKX2.1) (Diagnostic bio, Cat#8G7G3/1 1:500), anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (Santa Cruz, Cat#sc-374669; 1:400) .

Statistical analysis

In all statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, USA) was used to perform the Mann-Whitney U test. Data are presented as mean ± SD. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

We have used ChatGPT, DeepL and Grammarly to correct English grammar of the current manuscript. After using the service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The datasets of DNA sequencing from the SZT2 MT iPSCs are available in DDBJ repository (an INSDC member) under the accession numbers LC890385 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/LC890385) and LC890386 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/LC890386). The data are publicly accessible.

References

Toutzaris, D. et al. A novel giant peroxisomal superoxide dismutase motif-containing protein. Free Radic Biol. Med. 48, 811–820 (2010).

Basel-Vanagaite, L. et al. Biallelic SZT2 mutations cause infantile encephalopathy with epilepsy and dysmorphic corpus callosum. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 524–529 (2013).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Biallelic mutations in SZT2 cause a discernible clinical entity with epilepsy, developmental delay, macrocephaly and a dysmorphic corpus callosum. Brain Dev. 40, 134–139 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Clinical phenotype and genetic characteristics of SZT2 related diseases: A case report and literature review. Seizure 114, 111–120 (2024).

Peng, M., Yin, N. & Li, M. O. SZT2 dictates GATOR control of mTORC1 signalling. Nature 543, 433–437 (2017).

Wolfson, R. L. et al. KICSTOR recruits GATOR1 to the lysosome and is necessary for nutrients to regulate mTORC1. Nature 543, 438–442 (2017).

Lee, D. Y. Roles of mTOR signaling in brain development. Exp. Neurobiol. 24, 177–185 (2015).

Levitin, M. O. et al. Models of KPTN-related disorder implicate mTOR signalling in cognitive and overgrowth phenotypes. Brain 146, 4766–4783 (2023).

Saxton, R. A. & Sabatini, D. M. mTOR signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and disease. Cell 168, 960–976 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Induction of expansion and folding in human cerebral organoids. Cell. Stem Cell. 20, 385–396e3 (2017).

Andrews, M. G., Subramanian, L. & Kriegstein, A. R. mTOR signaling regulates the morphology and migration of outer radial glia in developing human cortex. Elife 9, e58737 (2020).

Hansen, D. V., Lui, J. H., Parker, P. R. L. & Kriegstein, A. R. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature 464, 554–561 (2010).

Lui, J. H., Hansen, D. V. & Kriegstein, A. R. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell 146, 18–36 (2011).

Lancaster, M. A. et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373–379 (2013).

Di Lullo, E. & Kriegstein, A. R. The use of brain organoids to investigate neural development and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 573–584 (2017).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Constitutive activation of mTORC1 signaling induced by biallelic loss-of-function mutations in SZT2 underlies a discernible neurodevelopmental disease. PLoS One. 14, e0221482 (2019).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Biallelic null variants in PNPLA8 cause microcephaly by reducing the number of basal radial glia. Brain 147, 3949–3967 (2024).

Nishino, K. et al. Defining hypo-methylated regions of stem cell-specific promoters in human iPS cells derived from extra-embryonic Amnions and lung fibroblasts. PLoS One. 5, e13017 (2010).

Iwao, T. et al. Differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into functional enterocyte-like cells using a simple method. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 29, 44–51 (2014).

Kondo, Y. et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid promotes the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells. PLoS One. 9, e104010 (2014).

Pollen, A. A. et al. Molecular identity of human outer radial glia during cortical development. Cell 163, 55–67 (2015).

Rosebrock, D. et al. Enhanced cortical neural stem cell identity through short SMAD and WNT Inhibition in human cerebral organoids facilitates emergence of outer radial glial cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 24, 981–995 (2022).

Bershteyn, M. et al. Human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids model cellular features of lissencephaly and reveal prolonged mitosis of outer radial glia. Cell. Stem Cell. 20, 435–449e4 (2017).

Gertz, C. C., Lui, J. H., LaMonica, B. E., Wang, X. & Kriegstein, A. R. Diverse behaviors of outer radial glia in developing ferret and human cortex. J. Neurosci. 34, 2559–2570 (2014).

Sun, T. & Hevner, R. F. Growth and folding of the mammalian cerebral cortex: from molecules to malformations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 217–232 (2014).

Kalebic, N. et al. Neocortical expansion due to increased proliferation of basal progenitors is linked to changes in their morphology. Cell. Stem Cell. 24, 535–550e9 (2019).

Nowakowski, T. J., Pollen, A. A., Sandoval-Espinosa, C. & Kriegstein, A. R. Transformation of the radial glia scaffold demarcates two stages of human cerebral cortex development. Neuron 91, 1219–1227 (2016).

Uzquiano, A. et al. Cortical progenitor biology: key features mediating proliferation versus differentiation. J. Neurochem. 146, 500–525 (2018).

Domingues, F. S. et al. Compound heterozygous SZT2 mutations in two siblings with early-onset epilepsy, intellectual disability and macrocephaly. Seizure 66, 81–85 (2019).

Fietz, S. A. et al. OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 690–699 (2010).

Calhoun, J. D. et al. mTORC1 functional assay reveals SZT2 loss-of-function variants and a founder in-frame deletion. Brain 145, 1939–1948 (2022).

Pollen, A. A. et al. Establishing cerebral organoids as models of Human-Specific brain evolution. Cell 176, 743–756e17 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Dysregulation of mTOR signalling is a converging mechanism in lissencephaly. Nature 638, 172–181 (2025).

Proietti Onori, M. et al. RHEB/mTOR hyperactivity causes cortical malformations and epileptic seizures through increased axonal connectivity. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001279 (2021).

Nguyen, L. H., Mahadeo, T. & Bordey, A. MTOR hyperactivity levels influence the severity of epilepsy and associated neuropathology in an experimental model of tuberous sclerosis complex and focal cortical dysplasia. J. Neurosci. 39, 2762–2773 (2019).

Lafourcade, C. A. et al. Rheb activation in subventricular zone progenitors leads to heterotopia, ectopic neuronal differentiation, and rapamycin-sensitive olfactory micronodules and dendrite hypertrophy of newborn neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 2419–2431 (2013).

Falcone, M. et al. An amino acid deletion inSZT2 in a family with non-syndromic intellectual disability. PLoS One. 8, e82810 (2013).

Ku, R. Y. & Torii, M. New molecular players in the development of callosal projections. Cells 10, 29 (2020).

Leone, D. P. et al. Satb2 regulates the differentiation of both callosal and subcerebral projection neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 25, 3406–3419 (2015).

Xiang, Y. et al. HESC-derived thalamic organoids form reciprocal projections when fused with cortical organoids. Cell. Stem Cell. 24, 487–497e7 (2019).

Sloan, S. A., Andersen, J., Pașca, A. M., Birey, F. & Pașca, S. P. Generation and assembly of human brain region-specific three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Protoc. 13, 2062–2085 (2018).

Lancaster, M. A. & Knoblich, J. A. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2329–2340 (2014).

Sakaguchi, H. et al. Generation of functional hippocampal neurons from self-organizing human embryonic stem cell-derived dorsomedial telencephalic tissue. Nat. Commun. 6, 8896 (2015).

Shimada, I. S., LeComte, M. D., Granger, J. C., Quinlan, N. J. & Spees, J. L. Self-renewal and differentiation of reactive astrocyte-derived neural stem/progenitor cells isolated from the cortical peri-infarct area after stroke. J. Neurosci. 32, 7926–7940 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The human iPSC line Windy was derived from a human embryonic lung fibroblast cell line (MRC-5) and obtained by Dr. Umezawa. Nagoya City University Institutional Review Board approved the protocol (No.70-20-0008).

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20H03646, 24K02424 and 24K02425 for SS and ISS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S., Y.N., M.F., I.S.S., Y.K., and S.S. designed the study, E.S. and Y.N. conducted the investigation, E.S. and S.S. wrote the original draft, Y.N., M.F., I.S.S., T.I., D.I., Y.N., A.H., and Y.K. reviewed and edited the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, E., Nakamura, Y., Fujimoto, M. et al. Brain organoid models of SZT2-related disease reveal an overproduction of outer radial glial cells through mTORC1 activation. Sci Rep 16, 5193 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35733-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35733-w