Abstract

High yield and high nitrogen use efficiency are blocked by various abiotic stress, especially in arid, salinity and irrigation deficiency agricultural production system. While systematic solutions are crucial strategies, the translation of problem-solving approaches into field-scale practical applications remains insufficient. This study aimed at designing a high yield and high efficiency production system by combined enhanced-efficiency fertilizers (EEFs) and best agronomic practices. The effects were examined through a 3-years (from 2020 to 2022) maize field experiment in a typical region, Hangjinhou Banner, inner Mongolia, China. The results show that 15–18 Mg ha−1 yield (80% of yield potential) can be realized under various stress conditions by adopted the new designed system. In this system, nitrogen (N) fertilizer input can be reduced from 380 kg ha−1 (higher yield practice) to 250 kg ha−1 (balance above-ground uptake), fertilization times can be reduced from 3 to 1, and the nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) can be increased to over 57.9%. The key is to reduce nutrient losses, prolong nutrient supply and control nutrient concentration by using enhanced efficiency fertilizer and increase crop yields from 13.5 to 15 Mg ha−1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arid and semi-arid regions, comprising over 30% of Earth’s terrestrial surface area, 42.9% of the world’s arable land, contributing 60% to world food production, and supporting more than 1.2 billion people, or 20% of the world’s population1,2,3. Nevertheless, irrigated agriculture in arid and semi-arid environment often faces major challenges. Among them, water shortage and soil salinization are the main limiting factors for irrigated agricultural production in arid and semi-arid regions4. With the growing population and the increasing demand for food, the application of nitrogen (N) fertilizers has been also increasing5. However, increased input of fertilizer did not bring higher yield, but aggravated the soil degradation, and brought ground water pollution, further lower the sustainability6,7. This issue has become more serious as global climate change has significant impacts on agricultural systems, i.e., frequent occurrence of drought.

Located in arid and semi-arid western Inner Mongolia, the Hetao Irrigation District (HID) is a typical semi-arid saline-alkali soil region. As a major grain and oil seed production region in China in thousands of years, this region is facing severe challenges. There are 18 million ha of farmland, and 7.1 million ha are relying on irrigation from the Yellow River, but the saline land area increased to 2 million ha due to flood irrigation. The annual precipitation is around 160 mm4, water shortages and increasing drought brought great uncertainty for crop yield8. The average maize yield has reached 8,706 kg ha−1 in 2010 s, which is higher than that in other production areas, such as in Northeast and North China9. However, the yield is stagnant in recent 10 years, and only realized 40% of yield potential. For example, Li et al. found that the grain yield potential in the HID reached 18 Mg by Hybrid-Maize model simulation10. How to close the yield gap is a ground challenge.

However, the input is already high, i.e. the N fertilizer input is as high as 300–450 kg N ha−1, exceeding most of the main maize producing areas in China, and the NUE is low at only 16–40%11. The saline-alkali land with higher pH (usually pH ≥ 8) and strong wind which generate great amount of ammonia volatilization, especially when farmer applied fertilizer by broadcasting. And the soil high pH also has high nitrification rate, which means most applied urea or ammonium base nitrogen will convert to nitrite, and then easily runoff with flood irrigation. Existing research show that nutrient loss, such as ammonia volatilization, denitrification, and N leaching losses reach 6.0%, 1.0%, and 22.8%, respectively12. Another statistic data show that in the HID, the amount of N entering ditches with farmland withdrawal water during autumn irrigation reaches 840 t per year, and N loss from farmland has become an important source of pollution in Wuliangsu Lake13. Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and minimizing nitrogen losses are critical not only for environmental conservation, but also for achieving high crop productivity.

Yield and nitrogen use efficiency need to be improved urgently in HID as well as similar regions. Some studies have explored the potential to improve nitrogen use efficiency through the optimization of N fertilizer application rates, application periods, and N fertilizer products14,15,16. those technologies can control N fertilizer inputs to above 300 kg ha−1 thus increasing NUE to 30%−40%17,18,19. However, this NUE is still far from the green development target, i.e. 54–63% based on the planetary boundaries’ framework20,21,22. To realize NUE target, it is need to reduce the N fertilizer input by 20–30%23. However, the grain yield of these efficient treatments was only 11–14 t, i.e. 50–60% of local yield potential. To meet green development target, i.e. realizing yield potential reaches 80%24,25, which need to be increased from 10 Mg to more than 15 Mg. Unfortunately, no report to show how to realize the due higher yield target (80% yield potential) and higher NUE (54–63%) in this region.

Synergistic high grain yields and higher nitrogen use efficiency rely on integrated technologies, such as right variety, rational planting density, and rational water and fertilization22,26. More importantly, the introduction of innovative technologies, while controlling ammonia volatilization, leaching, runoff, and multiple losses of N, is particularly important in this kind of high pH soils and high-water flooding conditions to mitigate the constraints from salt and alkali content7. Enhanced-efficiency fertilizers (EEFs), including controlled-release fertilizers, nitrification inhibitors, and urease inhibitors, can regulate nutrient loss and nutrient transformation, which are extremally important for higher NUE. Ammonium N may be beneficial for seedling emergence and the formation of strong plants under low-temperature and salt-stress conditions27,28. Mousavi Shalmani et al. even found that the 3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP) application promoted ammonium N assimilation and transfer to the shoots, which has created relative resistance to drought stress conditions29. However, The EEFs application method in the arid and semi-arid regions is still lacking, and only few studies have explored the role of single measures. For example, Sanz-Cobena et al. studied the ammonia volatilization reduction effect of urease inhibitors but did not achieve yields and NUE target30. To establish EEFs application techniques according to soil and climate conditions in arid and semi-arid regions, and to meet green development objectives, are important research topics.

In this study, focus on a high-yield, higher NUE and low-environmental impact target of maize in the HID (80% yield potential and 54–63% NUE), we designed a best nutrient management practices box by in cooperating with DMPP application mode basing on the unique soil, climatic, and production conditions in the HID. And tested the technologies efficiency through multi-year experiments.

Materials and methods

Study site

In this study, the fourth community of Lianzeng Village, Hangjinhou Banner, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (40°42′28″N, 107°2′8″E) was selected as the experimental site, which is located in the HID with a temperate continental arid climate. The annual precipitation in Hangjinhou Banner in 2020, 2021, and 2022 were 219.3, 125.6, and 68.3 mm, respectively. There was extremely low precipitation occurred in 2022, and seasonal drought occurred in June during the corn jointing period. The meteorological conditions from April to September during the 2020–2022 maize planting season are shown in Fig. 1.

The local soil is mainly cumulated irrigated soils with severe salinization, which are irrigated with water from the Yellow River, with three irrigations coinciding with fertilizer application during the maize-growing season. With the following basic characteristics: soil total nitrogen 1.12 g kg−1, Soil organic matter 15.3 g kg−1, Available phosphorus 10.06 mg kg−1, Available potassium 172 mg kg−1, pH 8.27.

Experimental design and treatments

The experimental treatments are shown in Table 1, control (CK, no N fertilization), high-yield practice (HP), high-yield and high-efficiency practice (HE, HP with 34% N reduction), high-yield and stress-tolerant practice (HS, HE with nitrification inhibitors). The plots were 11 m × 6 m, with 40 cm wide and 30 cm high ridges between the plots to prevent water and fertilizer from escaping. Each treatment had three replications arranged in randomized blocks, and the experiment was conducted over three years from 2020 to 2022, with a total of four treatments.

Two optimized treatments (HE and HS) were used to make the N input consistent with the aboveground uptake of the crop at the target yield31. Based on the N uptake of maize at 1.55 kg in 100 kg of kernels32 and the target yield, the optimized N application rate for maize in the HID was calculated to be 250 kg ha−1. This means that the nitrogen input is in balance with the amount taken away by the aboveground biomass.

Experimental material

The corn variety used was M751. which was bred by Monsanto Technology LLC and purchased from China Seed International Seed Co., Ltd. Nitrification inhibitor - DMPP (3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate), produced by Wuwei Jincang Bioscience Co., Ltd., were added to the urea and compound fertilizer before applied in to soil. The amount of DMPP added was 7‰ of total N (in-kind). During 2020–2022, the base fertilizer consisted of N fertilizer, phosphate fertilizer, and potash fertilizer. Phosphorus fertilizer was used as triple superphosphate (containing 42% P2O5) in the CK, diammonium phosphate (18–46–0) in the HP treatment, and monoammonium phosphate (12–61–0) in the remaining treatments. The potassium fertilizer used was uniform potassium chloride (59% K2O).

Based on the hybrid maize model, the density required to reach the target yield of 15–18 Mg ha−1 is more than 80,000 plants ha−133. In this study, to further explore the biological potential of variety, a newly introduced local high-yielding variety of maize (M751) was sown at a density of 90,000 plants ha−1 from 2020 to 2022. Tillage and plant protection measures were implemented according to the local high-yield and high-efficiency technical regulations.

Measurement and methods

Grain yield was measured at harvest, and yield components were determined. Aboveground plants of maize at maturity were taken during the growing season and divided into stem sheaths, leaves, spike stalk, and grains, and dry matter mass. For each part, total N content was measured. The total phosphorus content of aboveground plants was measured in 2022.

N use efficiency and other indexes were calculated as recommend by Zhang et al.34:

The N surplus from fertilizer N application was calculated for each crop as the difference between applied fertilizer N (NF) and N removed from the field in the harvested grain (NG), using a simple balance calculation, the gaseous loss as well as the atmospheric deposition of N were not included in these calculations in order to reduce the degree of error35:

The N balance for each crop was calculated as the difference between N inputs (In) and N outputs (Out):

where NR IN is N contained in the residues of previous crop and NR OUT is N contained in the harvested crop’s residues.

Statistical analysis

The comparisons among different treatments were based on Duncan’s test at the 0.05 probability level (p < 0.05). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for grain yield, yields components, dry matter weight, N and P uptake, mineral N contents and N efficiency using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Institute Inc.).

Results

Dry matter accumulation and N uptake

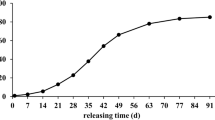

Although the soil accumulated great amount of nitrogen (1.12 g kg−1), stop nitrogen input significantly decreased yield. The biomass of CK was only 10–17 Mg ha−1during 2020–2022. However, N input significantly increased biomass, the HP and two optimized treatments reached 22.7–29.4 Mg ha−1. Meanwhile, the difference was relatively significant between 3 years. In particular, biomass is lower under extreme drought conditions in 2022 than in both 2020 and 2021. Relative to higher yield practice (HP 380 kg ha−1), high-yield and stress-tolerant practice (HS) that reduced the rate N fertilizer to 250 kg ha−1 could achieve biomass consistent with HP. Whereas the high-yield and high-efficiency practice (HE) was able to maintain biomass in normal rainfall years 2020 and 2021, but under drought conditions in 2022 (with precipitation reduced 48.3–68.8%), the biomass was significantly lower than HP and HS (Fig. 2d), the losses of biomass was mainly in the grains (Fig. 2c).

Effects of different treatments on dry matter accumulation during maturation stage. CK (no N fertilization), HP (high-yield practice), HE (high-yield and high-efficiency practice), HS (high-yield and stress-tolerant practice). The vertical bars indicate standard deviations, and the different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

With the depletion of soil fertility, aboveground N uptake decreased annually, and the overall performance of N uptake of CK during 2020–2022 was significantly lower than that of all the N treatments (Fig. 3). However, the two optimized treatments (HE and HS) appeared to be significantly lower, primarily in grain nitrogen uptake, even though the EEFs did not exhibit a significant promoting effect in 2021 (Fig. 3b). In 2022, N uptake in the grain and aboveground part of HE was significantly lower than that of the HP treatment (Fig. 3c, d), whereas the application of EEFs (HS) did not differ from the HP. Overall, reducing N application from 380 to 250 kg ha−1 had no significant effect on nitrogen allocation.

Effects of different treatments on N uptake during maturation stage. CK (no N fertilization), HP (high-yield practice), HE (high-yield and high-efficiency practice), HS (high-yield and stress-tolerant practice). The vertical bars indicate standard deviations, and the different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Grain yields and yield components

During 2020 to 2022, the yield of the CK rarely exceeded 10 Mg ha−1, and with the continuous depletion of land productivity, the yield showed a continuous decline (Fig. 4a). The yield in 2022 was 5,384 kg ha−1, which was only 1/3 of that from the HP treatment, indicating that the N supply capacity of the local soil was very low. The optimal yields in the N application treatments reached the high-yield target of 15–18 Mg ha−1, which shows that N fertilizer application is an important guarantee for high yield in the HID. On reducing the amount of N fertilizer used by higher yield practice (380 kg ha−1) to aboveground uptake (250 kg) and by not applying any EEFs (HE), the yield level during 2020–2021 was in line with that of the HP treatment. However, the yield level in 2022 significantly decreased by 12.82% owing to seasonal drought at the maize jointing stage, high-yield and stress-tolerant practice (HS) insignificantly reduced yield. Conversely, one-time nitrification inhibitors basal application significantly increased yield by 15.06% compared with the HE.

In the three years, reducing the N application to 250 kg ha−1 had no significant effect on the number of spikes and kernel per ear, and the differences were mainly in the 100-kernel weight (Fig. 4). In terms of 100-kernel weight (Fig. 4d), N reduction (HE) was significantly reduced by 2.26% compared with that of the HP treatment in 2020, and there was no difference between the HS or HP treatments. However, the 100-kernel weight of nitrification inhibitors (HS) was 2.32% significantly higher than that of HP and 2.03% higher than that of HE in 2022.

Effects of different treatments on grain yield and yield components. CK (no N fertilization), HP (high-yield practice), HE (high-yield and high-efficiency practice), HS (high-yield and stress-tolerant practice). The vertical bars indicate standard deviations, and the different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Phosphorus uptake

Figure 5 shows the phosphorus absorption of maize at different growth stages under different treatments in 2022. Before the jointing stage, there were no significant differences among the nitrogen treatments, but in the maturity period, adding nitrification inhibitors (HS) increased phosphorus absorption by 22.3% compared with HE, and there was no significant difference from the HP.

Effects of different treatments on P uptake. CK (no N fertilization), HP (high-yield practice), HE (high-yield and high-efficiency practice), HS (high-yield and stress-tolerant practice). JS (Jointing stage), TS (Tasselling stage), FS (Filling stage), MS (Maturity stage). The vertical bars indicate standard deviations, and the different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Nitrogen use efficiency

The N use efficiency of the different treatments for three years 2020–2022 are shown in Table 2. There was a significant on PFPN, AEN and REN, but not on PEN in three years. The PFPN and AEN did not differ among the optimized treatments (HE and HS) in 2020–2021, all of which were significantly higher than that in the HP treatment. However, the treatment of nitrification inhibitors (HS) was significantly higher than that of the HE treatment in 2022. In terms of REN, HE and HS were significantly higher than HP during 2020 to 2021, of which the EEFs treatments had achieve the green development goal (60%). In 2022, The REN had made variation under the extreme drought climate, was lower than 60% for all treatments. However, under the high-yield and stress-tolerant practice (HS), the use of nitrification inhibitors significantly enhanced REN.

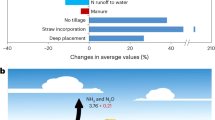

N surplus and balance

The highest total nitrogen input (NF + NR) was observed in 2021, with up to 453 kg N ha−1 (HP) applied to the field (Fig. 6). Nitrogen inputs for HE and HS treatments peaked in 2021 at 313 and 320 kg N ha−1, respectively. N content in harvested grain was similar across all fertilization treatments, reflecting grain yields obtained throughout the experiment (Fig. 4). The maximum yield of 284 kg N ha−1 was achieved under HP in 2020. The minimum yield of 229 kg N ha−1 occurred in 2022 due to extreme drought conditions.

Optimizing nitrogen fertilizer management can significantly reduce N surplus and N balance. From 2020 to 2022, the HP treatment exhibited the highest positive nitrogen surplus (NF-NG) and nitrogen balance (Input-Output), showing significant differences compared to HE and HS. The maximum nitrogen surplus of 203 kg N ha−1 and maximum nitrogen balance of 217 kg N ha−1 were observed in 2022. Throughout the trial period, nitrogen surplus and nitrogen balance were comparable between HE and HS treatments, with HS yielding lower calculated values than HE. No significant differences were observed between treatments. In 2022, HE exhibited the highest post-harvest nitrogen surplus (93 kg N ha−1) and nitrogen balance (102 kg N ha−1). In 2020, the HS treatment exhibited the lowest nitrogen surplus at 51 kg N ha−1, with the lowest calculated nitrogen balance value of −19 kg N ha−1. For the control treatment, both nitrogen surplus and nitrogen balance calculations yielded negative values.

Analysis of N balance under different N treatments. CK (no N fertilization), HP (high-yield practice), HE (high-yield and high-efficiency practice), HS (high-yield and stress-tolerant practice). NR (N contained in plant residues), NG (N contained in grain), NF (fertilized N in kg ha−1). The vertical bars indicate standard deviations, and the different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Discussion

How the application of EEFs can ensure high crop yield and efficiency in the HID has been underreported. This study shows that it is a significant challenge to achieve high yield and high efficiency of maize under the unique soil and climate conditions of high pH, high salinity, flood irrigation, and drought in the HID. Reducing N fertilizer input can achieve high yields, but there is a risk of yield reduction under extreme arid climate conditions. Nevertheless, the combined application of EEFs can alleviate this risk.

The dry matter accumulation of the maize is a prerequisite for high yields, and improving the distribution of dry matter to the spike is key to high yields36. Only reducing N fertilizer application tends to reduce biomass. Srivastava et al. found that reducing N fertilizer significantly reduced the aboveground biomass, which is consistent with the results of our study37. The mechanism of securing the biomass in basal fertilizer applied with nitrification inhibitors may be that both the N form and the total amount of N at the earlier stage promote the development of the root system, which increases the root system’s water and nutrient uptake capacity in the later stage of the drought38,39. Ultimately, the 100-kernel weights increased. In 2020, the results showed that the reduction in N treatment was significantly lower than the HP treatment, while the aboveground N uptake could be maintained using the EEFs. Reasonable N fertilizer management can increase N uptake, promote N transfer to seeds, and improve NUE40,41. In the present study, we found that nitrification inhibitors and controlled-release fertilizers had desirable effects on N uptake and distribution, improved N uptake in the early stages, and promoted N transfer from nutrient organs to seeds in the late stages.

N reduction resulted in a significant reduction in the number of grains in 2022, and multiple years of research showed that 38% N reduction had no significant effect on the ear grain number of maize17. However, the results of our study differed from this because of the drought climate that led to a reduction in the number of grains per spike. A one-time application of nitrification inhibitors in 2022 significantly increased the 100-kernel weight, because the nitrification rate is fast in the local high pH soil. Nitrification inhibitors inhibit the conversion of ammonium N to nitrate N in the soil42, increasing the content of ammonium N, which then enhances N supply capacity at the late stage of maize growth, promotes the uptake of ammonium N in the maize and N accumulation in the kernels, and simultaneously improves 100-kernel weight.

In 2020–2021, the yield of the N reduction treatment was not significantly different from that of higher yield practice, and 34% N reduction could reach the high-yield target of 15–18 Mg (80% of the yield potential) in normal years, which fully demonstrated that the current constraints to high yields for farmers were not N fertilizer rate but the cooperation of other agronomic measures. However, the yield was significantly reduced by 12.82% compared with the HP in 2022 because of an extreme drought, as water deficit affects crop growth and kernel formation leading to yield reduction43,44,45. In contrast, the adoption of EEFs significantly increased grain yield in 2022. Numerous studies have shown that the use of EEFs can increase yield46,47,48. The results suggest that the optimized N application rate (250 kg ha−1) based on crop demand without changing irrigation and fertilizer products can support high yield in normal years but there is still a risk of yield reduction under abnormal climatic conditions. whereas the use of EEFs applications can reduce the risk of yield reduction due to arid climates, especially nitrification inhibitors. NH4+–N application can reduce the effects of drought stress on plant growth49, while NO3−–N has the opposite effect50. Therefore, the application of nitrification inhibitors inhibits soil nitrification, increases soil ammonium N content, and improves crop resistance under drought conditions.

In the 2022, it was found that the application of nitrification inhibitors could enhance the crop’s absorption of phosphorus, mainly due to inhibition of nitrification, which led to higher content of ammonium nitrogen in the soil51.Therefore, these results reaffirm that the decrease of the pH due to release of H by plants during ammonium uptake can have a strong influence on the solubilization of insoluble phosphates in soil52, improving the crop’s absorption of phosphorus and increasing crop yield53,54.

Achieving both high yield and nitrogen use efficiency has become a major challenge. The multi-year yields showed that the yields of the HP treatment could reach up to 15–18 Mg, but the REN was less than 50%. However, decreased N input can have higher REN, The REN of N reduction treatments were higher to the green development goal (60%). This suggested that technical and management measures to reduce N fertilizer application while maintaining crop yields could improve NUE21,55. Additionally, the application of nitrification inhibitors can significantly increase REN in the 2022. Three published meta-analysis showed that combination with EEFs can improve crop yields and NUE43,48,56.

The research presented here shows that the adaptation of N application rates to crop demand, as described Ladha et al. can reduce both N surplus and balance without affecting the yield level of the cropping system57. The N surplus of the optimized treatments was reduced to less than 93 kg N ha−1, while N application according to higher yield practice (HP) resulted in N surpluses of above 169 kg N ha−1 for each of the three years observed in this experiment. As documented in several pieces of research58,59, nitrogen applied in quantities exceeding crop demand is susceptible to loss via multiple pathways without influencing the yield of crops. In this experiment, we could not determine a clear advantage of nitrification inhibitors (HS) in comparison to 34% N reduction (HE) with regards to N balance and surplus calculations.

In this study, to further utilize the potential of density and varieties in the HID, the newly introduced high-yielding local varieties were used to increase the planting density to 90,000 plants ha−1 and further increase the yield to 18 Mg, which has already reached the local high-yield level. Therefore, it is difficult to improve yield by considering only varieties and planting densities. From the perspective of water and fertilizer management, precise water and fertilizer management can improve NUE and reduce environmental damage60,61. In addition, 34% N reduction can guarantee 80% of the local yield potential, while under an extreme drought climate, yield will be reduced. Combined with EEFs, which can alleviate the risk of yield reduction, the use of nitrification inhibitors in the HID has a better effect.

Conclusion

This study reveals that in saline and semi-arid regions, a combination of measures can achieve high yields and efficiency, with nitrification inhibitors mitigating the negative effects of arid climates on maize. Overall, an N fertilizer input of 250 kg ha−1 can support the N demand of spring maize with a yield of 15–18 Mg ha−1. N reduction in a normal year can guarantee high yields. However, seasonal droughts lead to lower yields. The combination of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers can mitigate the risk of yield reduction, especially the application of nitrification inhibitors to improve dry matter allocation, N uptake, and 100-kernel weight, thus achieving higher yields. In the saline and arid regions of Northwest China, the N reduction alone may have a risk, and a combination of new products must be considered. The application of nitrification inhibitors in the HID can achieve one-time fertilization and ensures the supply of ammonium N under arid climate, which probably helps the root system of seedlings to grow and improves resilience. Therefore, the nitrification inhibitors can mitigate the risk of yield reduction under extreme drought conditions in the semi-arid and saline-alkali area.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wickens, G. E. Ecophysiology of Economic Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands, 5–15 (eds Wickens, G. E.) (Springer, 1998).

Prăvălie, R. Drylands extent and environmental issues. A global approach. Earth Sci. Rev. 161, 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.08.003 (2016).

Liu, W. D. & Chen, Y. C. Regulation of agro-ecosystems in semi-arid (dry) areas. Inner Mongolia Agricultural Sci. Technol. 04, 1–7 (1991).

Cao, Z. D., Zhu, T. J. & Cai, X. M. Hydro-agro-economic optimization for irrigated farming in an arid region: the Hetao irrigation District, inner Mongolia. Agric. Water Manage. 277, 108095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.108095 (2023).

Beek, C. L., Meerburg, B. G., Schils, R. L. M., Verhagen, J. & Kuikman, P. J. Feeding the world’s increasing population while limiting climate change impacts: linking N2O and CH4 emissions from agriculture to population growth. Environ. Sci. Policy. 13, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2009.11.001 (2010).

Guo, J. H. et al. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327, 1008–1010. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182570 (2010).

Zhang, X. A plan for efficient use of nitrogen fertilizers. Nature 543, 322–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/543322a (2017).

Liu, J., Sun, S. K., Wu, P. T., Wang, Y. B. & Zhao, X. N. Evaluation of crop production, trade, and consumption from the perspective of water resources: A case study of the Hetao irrigation district, China, for 1960–2010. Sci. Total Environ. 505, 1174–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.088 (2015).

Li, W. B. et al. Study on index system of optimal fertilizer recommendation for spring corn in Hetao irrigation area of inner Mongolia. Scientia Agricultura Sinica. 45, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2012.01.011 (2012).

Li, J. Y. et al. Understanding yield gap and production potential based on networked variety-density tests and hybrid-maize model in maize production areas of Inner Mongolia. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. https://doi.org/10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.16015 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. Determination of input threshold of nitrogen fertilizer based on environment-friendly agriculture and maize yield. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 32, 8. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2016.12.020 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Effects of three types of soil amendments on yield and soil nitrogen balance of maize-wheat rotation system in the Hetao irrigation Area, China. J. Arid Land. 11, 904–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-019-0005-x (2019).

Du, J. et al. Nitrogen balance in the farmland system based on water balance in Hetao irrigation district. Acta Ecol. Sin. 31, 11 (2011).

Li, Y. Q., Liu, G., Hong, M., Wu, Y. & Chang, F. Effect of optimized nitrogen application on nitrous oxide emission and ammonia volatilization in Hetao irrigation area. Acta Sci. Circum. 39, 7. https://doi.org/10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2018.0321 (2019).

Zhao, N. et al. Effects of the different stage of nitrogen fertilizer application on maize yield in cultural pattern of one hole double plants. J. North. Agric. 048, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.12190/j.issn.2096-1197.2020.01.05 (2020).

Zheng, J. et al. Wheat straw mulching with nitrification inhibitor application improves grain yield and economic benefit while mitigating gaseous emissions from a dryland maize field in Northwest China. Field Crops Res. 265, 108125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108125 (2021).

Jin, L. B. et al. Effects of integrated agronomic management practices on yield and nitrogen efficiency of summer maize in North China. Field Crops Res. 134, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.04.008 (2012).

Zhou, L. F. et al. Drip irrigation lateral spacing and mulching affects the wetting pattern, shoot-root regulation, and yield of maize in a sand-layered soil. Agric. Water Manage. 184, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2017.01.008 (2017).

Ren, B. Z., Huang, Z. Y., Liu, P., Zhao, B. & Zhang, J. W. Urea ammonium nitrate solution combined with urease and nitrification inhibitors jointly mitigate NH3 and N2O emissions and improves nitrogen efficiency of summer maize under fertigation. Field Crops Res. 296, 108909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2023.108909 (2023).

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Managing nitrogen for sustainable development. Nature 528, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15743 (2015).

Li, T. Y. et al. Exploring optimal nitrogen management practices within site-specific ecological and socioeconomic conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 241, 118295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118295 (2019).

Gao, Y., Wu, P. T., Zhao, X. N. & Wang, Z. K. Growth, yield, and nitrogen use in the wheat/maize intercropping system in an arid region of Northwestern China. Field Crops Res. 167, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2014.07.003 (2014).

Lobell, D. B., Cassman, K. G. & Field, C. B. Crop yield gaps: their Importance, Magnitudes, and causes. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.environ.041008.093740 (2009).

van Ittersum, M. K. & Cassman, K. G. Yield gap analysis—Rationale, methods and applications—Introduction to the special issue. Field Crops Res. 143, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.12.012 (2013).

Assefa, Y. et al. Analysis of long term study indicates both agronomic optimal plant density and increase maize yield per plant contributed to yield gain. Sci. Rep. 8, 4937. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23362-x (2018).

Fernández-Crespo, E., Camañes, G. & García-Agustín, P. Ammonium enhances resistance to salinity stress in citrus plants. J. Plant. Physiol. 169, 1183–1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2012.04.011 (2012).

Hessini, K. et al. Interactive effects of salinity and nitrogen forms on plant growth, photosynthesis and osmotic adjustment in maize. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 139, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.03.005 (2019).

Mousavi Shalmani, M. A. et al. Nitrification inhibitor application at stem elongation stage increases soil nitrogen availability and wheat nitrogen use efficiency under drought stress. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 69, 2020–2037. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2022.2132387 (2023).

Sanz-Cobena, A., Sánchez-Martín, L., García-Torres, L. & Vallejo, A. Gaseous emissions of N2O and NO and NO3 – leaching from Urea applied with Urease and nitrification inhibitors to a maize (Zea mays) crop. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 149, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.12.016 (2012).

Ju, X. T. & Christie, P. Calculation of theoretical nitrogen rate for simple nitrogen recommendations in intensive cropping systems: A case study on the North China plain. Field Crops Res. 124, 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2011.08.002 (2011).

Yue, S. C. et al. Validation of a critical nitrogen curve for summer maize in the North China Plain. Pedosphere 24, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(13)60082-X (2014).

Guo, J. M. Optimizing nitrogen management for high-yielding maize (Zea maysl.) in Northwest China by using controlled-release fertilizer (2016).

Zhang, F. S. et al. Nutrient use efficiencies of major cereal crops in China and measures for improvement. Acta Pedol. Sin. 045, 915–924 (2008).

Hartmann, T. E. et al. Nitrogen dynamics, apparent mineralization and balance calculations in a maize – wheat double cropping system of the North China plain. Field Crops Res. 160, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2014.02.014 (2014).

Shang, Y. P. et al. Effects of green manure application methods on dry matter accumulation, distribution, and yield of maize in Oasis irrigation area. Acta Agron. Sinica. 50, 686–694 (2024).

Srivastava, R. K., Panda, R. K., Chakraborty, A. & Halder, D. Enhancing grain yield, biomass and nitrogen use efficiency of maize by varying sowing dates and nitrogen rate under rainfed and irrigated conditions. Field Crops Res. 221, 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2017.06.019 (2018).

Xu, L. et al. Nitrogen transformation and plant growth in response to different urea-application methods and the addition of DMPP. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Sci. 177, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201100390 (2014).

Zhu, J. J., Dou, F. F., Phillip, F. O., Liu, G. & Liu, H. F. Effect of nitrification inhibitors on photosynthesis and nitrogen metabolism in ‘Sweet sapphire’ (V. vinifera L.) grape seedlings. Sustainability 15 (2023).

Xia, L. L. et al. Can knowledge-based N management produce more staple grain with lower greenhouse gas emission and reactive nitrogen pollution? A meta-analysis. Global Change Biol. 23, 1917–1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13455 (2017).

Lu, J. S. et al. Nitrogen fertilizer management effects on soil nitrate leaching, grain yield and economic benefit of summer maize in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manage. 247, 106739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106739 (2021).

Akiyama, H., Yan, X. & Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: meta-analysis. Global Change Biol. 16, 1837–1846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02031.x (2010).

Gu, B. J. et al. Cost-effective mitigation of nitrogen pollution from global croplands. Nature 613, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05481-8 (2023).

Liu, C. R. et al. Nitrogen stabilizers mitigate nitrous oxide emissions across maize production areas of china: A multi-agroecosystems evaluation. Eur. J. Agron. 143, 126692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2022.126692 (2023).

You, L. C. et al. Global mean nitrogen recovery efficiency in croplands can be enhanced by optimal nutrient, crop and soil management practices. Nat. Commun. 14, 5747. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41504-2 (2023).

Qiao, C. L. et al. How inhibiting nitrification affects nitrogen cycle and reduces environmental impacts of anthropogenic nitrogen input. Global Change Biol. 21, 1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12802 (2015).

Yang, X. L., Lu, Y. L., Tong, Y. A. & Yin, X. F. A 5-year lysimeter monitoring of nitrate leaching from wheat–maize rotation system: comparison between optimum N fertilization and conventional farmer N fertilization. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 199, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.08.019 (2015).

Li, T. Y. et al. Enhanced-efficiency fertilizers are not a panacea for resolving the nitrogen problem. Global Change Biol (2018).

Gao, Y. X. et al. Ammonium nutrition increases water absorption in rice seedlings (Oryza sativa L.) under water stress. Plant. Soil. 331, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0245-1 (2010).

Ye, J. Y., Tian, W. H. & Jin, C. W. Nitrogen in plants: from nutrition to the modulation of abiotic stress adaptation. Stress Biol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44154-021-00030-1 (2022).

Barth, G. et al. Performance of nitrification inhibitors with different nitrogen fertilizers and soil textures. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Sci. 182, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201800594 (2019).

Vogel, C. et al. Effects of a nitrification inhibitor on nitrogen species in the soil and the yield and phosphorus uptake of maize. Sci. Total Environ. 715, 136895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136895 (2020).

Jing, J., Zhang, F., Rengel, Z. & Shen, J. Localized fertilization with P plus N elicits an ammonium-dependent enhancement of maize root growth and nutrient uptake. Field Crops Res. 133, 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.04.009 (2012).

Li, S., Liu, Y., Sha, Z., Li, S. & Yang, Q. Adding nitrification inhibitors to N fertilisers induces rhizosphere acidification and enhances P acquisition: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 151, 126967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2023.126967 (2023).

Yang, X. L. et al. Optimising nitrogen fertilisation: A key to improving nitrogen-use efficiency and minimising nitrate leaching losses in an intensive wheat/maize rotation (2008–2014). Field Crops Res. 206, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2017.02.016 (2017).

Sha, Z. P. et al. Effect of N stabilizers on fertilizer-N fate in the soil-crop system: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 290, 106763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106763 (2020).

Ladha, J. K., Pathak, H., Krupnik, J., Six, T. & van Kessel, C. J. Adv. Agron. Vol. 87, 85–156 (Academic Press, 2005).

Ju, X. T. et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 3041–3046. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0813417106 (2009).

Ding, W. et al. Estimating regional N application rates for rice in China based on target yield, Indigenous N supply, and N loss. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114408 (2020).

Liu, H. J. et al. Evaluation on the responses of maize (Zea Mays L.) growth, yield and water use efficiency to drip irrigation water under mulch condition in the Hetao irrigation district of China. Agric. Water Manage. 179, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2016.05.031 (2017).

Zhang, T. B., Zou, Y. F., Kisekka, I., Biswas, A. & Cai, H. J. Comparison of different irrigation methods to synergistically improve maize’s yield, water productivity and economic benefits in an arid irrigation area. Agric. Water Manage. 243, 106497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106497 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Research Project on Synergist Formulations Based on Different Application Scenarios.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Research Project on Synergist Formulations Based on Different Application Scenarios.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Zeng wrote the main manuscript text, collected and analyzed the data and built the figures and tables; L. Wu involved in the experiment design and collected the data; J. Liu, Z. Li, B. Li and Z. Duan wrote the manuscript; W. Zhang: Writing – wrote the manuscript and his project has funded the publication fee of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Z., Wu, L., Liu, J. et al. Synergistic nitrification inhibitors with best management practices can achieve higher yield and nitrogen use efficiency in semi-arid saline-alkali soils. Sci Rep 16, 5287 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36007-1