Abstract

Understanding population movement during natural disasters is critical for emergency response, resource allocation, and risk mitigation. This study proposes a kernel-based flow extraction framework to infer directional human mobility from aggregated, trajectory-free mobile network data. By integrating kernel density estimation (KDE) and a modified gravity model, the method generates spatiotemporal vector fields that capture flow dynamics without requiring individual tracking. The framework is applied to a case study of the 2025 ML 6.4 (Mwg 5.8) Dapu earthquake in southern Taiwan, using mobile communication data aggregated in 500 m × 500 m grids at 10-minute intervals. The analysis reveals significant mobility changes following the seismic event, with directional shifts transitioning from outward dispersal to inward convergence, especially in densely populated zones. Temporal peaks in anomalous flow patterns were detected within the first hour post-event, with variations across seismic intensity levels and population densities. These findings highlight the spatial heterogeneity of behavioral responses to disasters and underscore the utility of the proposed approach for identifying critical zones of disruption. The framework offers a scalable, privacy-preserving tool for real-time disaster monitoring and supports the development of early warning systems and urban resilience planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human movement is of paramount importance in addressing unforeseen disasters, which often result in devastating casualties. The reasons include evacuation planning, resource allocation, casualty reduction, infrastructure resilience, and post-disaster recovery. Numerous scholarly articles have documented the variations in human mobility patterns during disaster events1,2,3. These studies provide detailed analyses of how pedestrian flows are affected by the onset of crises, revealing both quantitative changes and underlying behavioral responses. In addition, these works offer insights into the broader implications of such dynamics for emergency preparedness and response strategies.

The dynamics of population movement are often disrupted by external incidents such as earthquakes, typhoons, and bombings. These events can lead to sudden changes in human mobility patterns, often resulting in traffic congestion or population displacement away from affected zones4,5,6. Understanding these deviations is critical for hazard response and urban resilience planning, as they reveal behavioral adaptations under stress and help inform emergency logistics and public safety measures.

Various methods and data sources have been applied to study population movement, each offering different temporal and spatial resolutions. Traditional approaches, such as census data, can depict general movement patterns; however, they are often constrained by infrequent updates and limited timeliness, reducing their effectiveness in fast-changing hazard contexts.

To address these limitations, researchers have increasingly turned to alternative data sources. Brockmann et al.7 examined the movement of banknotes across the United States to explore the spatial dynamics of human travel and their implications for the spread of infectious diseases—an issue closely tied to hazard modeling. With the widespread adoption of mobile communication technologies, the large volumes of data generated by these devices have become instrumental in capturing the spatiotemporal patterns of human mobility—commonly referred to as human travel behavior or flow dynamics. Song et al.8 utilized anonymized mobile phone data to investigate the predictability of individual movement, revealing that despite personal variation, human trajectories tend to follow highly regular patterns, allowing for robust forecasting. In a privacy-sensitive approach, Palchykov et al.9 derived mobility patterns from aggregated mobile phone call data, providing insights into collective movement without individual-level tracking. Phithakkitnukoon et al.10 investigates the relationship between human mobility and social networks, using one year of anonymized mobile phone data from over 1.3 million users in Portugal.

The use of mobile data has proven instrumental in understanding human mobility patterns under natural hazard conditions. Such data facilitate the identification of evacuation trajectories, displacement dynamics, and temporal fluctuations in population flow during emergency phases2,11. By capturing anomalies relative to normative mobility baselines—such as rapid outflows, congestion near infrastructure nodes, or altered commuting routes—these systems support the detection of hazard-induced disruptions and emergent behaviors in situ12. These deviations not only provide empirical evidence of adaptive strategies but also serve as proxy indicators for vulnerability hotspots and resource strain.

Complementary to mobile-derived insights, the integration of geotagged social media content has gained prominence as a method for real-time monitoring of population dynamics during hazard events. Platforms such as Twitter and Instagram enable the spatial and temporal tracking of user-generated posts, offering an additional data layer that enhances granularity and situational awareness. Investigations by Tsou13, Han et al.14, and Li et al.15 emphasize the utility of such data in mapping behavioral responses, locating concentration zones, and understanding the evolution of community sentiment in crisis contexts.

Multiple data sources are used to investigate human mobility, including social media activity, GPS logs from vehicles, and location data from mobile devices—either via GPS or cellular tower-based triangulation, the latter of which varies in resolution depending on tower density. These mobility datasets can generally be divided into two categories: individual trajectory data and aggregated non-trajectory data, each offering unique analytical benefits.

Trajectory-based data captures the detailed movement paths of individuals or groups across spatial and temporal dimensions. These are typically visualized using flow lines, arrows, or streaks that represent direction and intensity of movement. While highly informative, such data often require partnerships with telecommunications providers and are subject to stringent privacy restrictions16,17. Moreover, transforming raw location logs into usable trajectories demands significant preprocessing, including data cleaning, interpolation, and modeling.

In contrast, non-trajectory data provides aggregated counts of population distribution across different time intervals and spatial resolutions. Rather than tracking individual entities, these datasets offer snapshots of population density at specific times, making them valuable for monitoring broad trends18. Visualization tools such as sequential heatmaps or choropleth maps are commonly used to examine changes across time frames, helping researchers identify macro-level mobility trends19. However, the lack of individual-level resolution means that these methods cannot capture detailed movement directionality or behavioral nuances.

To address the challenge of inferring directional human movement from aggregated spatiotemporal data, various methodological approaches have been proposed. Kim et al.20 developed a flow extraction method based on the gravity model, which applies adjustable smoothing through neighboring grid selection and estimates directional flow using point-to-point vector computations. While this approach allows for the visual identification of flow patterns before and after specific events, it falls short in providing detailed statistical insights. In particular, it does not support direct quantification of directional changes over time or enable the systematic identification of locations exhibiting significant deviations in movement patterns.

Lin and Chan21 adapted an edge-detection algorithm from image processing to detect spatial gradients across three consecutive time frames of mesh-based population data. This technique infers movement direction based on gradient changes, but its application is limited by the lack of kernel customization and its reliance on spatial continuity, reducing its effectiveness for datasets characterized by discrete or unevenly distributed observations.

To address the limitations of existing methods for capturing directional human mobility from aggregated spatiotemporal data, this study introduces a flow extraction framework based on a kernel-driven modeling approach. The proposed method enables efficient and flexible estimation of population flow directions and magnitudes, while also supporting detection of regions with significant temporal changes in flow dynamics through comparative analysis across time intervals. Converting sparse data distributions into continuous surface data provides a robust foundation for capturing directional patterns of human mobility. Kernel parameters within the flow-extraction model can be tested and adjusted according to user requirements. Based on our sensitivity analysis, we provide reference information to guide parameter adjustments when applying this model. As a case study, this framework is applied to examine human mobility patterns in response to a seismic event that struck southern Taiwan on January 21, 2025. The areas identified through this analysis may serve as critical indicators for delineating disaster early warning regions and improving the situational awareness necessary for rapid emergency response.

Data and methods

Study area and seismic event

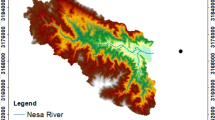

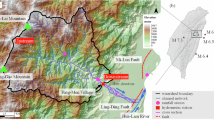

The 2025 Dapu earthquake occurred within the tectonically active region of southwestern Taiwan (Fig. 1), an area shaped by the ongoing convergence between the Eurasian and Philippine Sea plates. This tectonic interaction has long been associated with pronounced crustal deformation and frequent seismic activity22,23.

The earthquake struck on January 21, 2025, at 00:17 local time (UTC + 8), with its epicenter located at 120.55° E, 23.22° N and a focal depth of approximately 15 km. Seismological analyses conducted by the Central Weather Administration (CWA) and the Broadband Array in Taiwan for Seismology (BATS) identified the event as resulting from thrust faulting24. Notably, peak ground acceleration (PGA) exceeded 2 g at Station C102, situated near the epicenter, indicating intense ground shaking in the immediate vicinity (CWA 2025, refer to https://scweb.cwa.gov.tw/en-us/earthquake/data, last accessed on 15 June 2025).

The local magnitude (ML) of the Dapu earthquake was reported as 6.4 on the Richter scale by the CWA. According to the Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT) Project (https://www.globalcmt.org/, accessed 24 December 2025), the seismic scalar moment was estimated at \(\:1.75\times\:{10}^{25}\) dyn cm, corresponding to a moment magnitude (Mw) of 6.1. However, for small to intermediate events, Mw has been shown to exhibit systematic bias and poor consistency with body-wave and surface-wave magnitudes at the global scale25,26. To address these limitations, Das et al. proposed a new magnitude scale, termed the generalized seismic moment magnitude (Mwg). Based on this framework, the Mwg of the Dapu event is inferred to be 5.8, providing a more accurate representation of earthquake size and ensuring broader applicability across diverse tectonic settings.

Su et al.27 reported that buried fault structures significantly amplified ground motion, particularly on hanging-wall sites, highlighting the presence of a focusing effect. Beyond strong-motion records, geodetic and remote sensing data also revealed substantial subsurface fault slip and widespread ground deformation associated with the event28.

Structural damage was most pronounced in the Nansi and Yujing districts of Tainan city in southern Taiwan, both situated in close proximity to the earthquake’s epicenter. Field investigations and preliminary damage assessments confirmed a high concentration of building damage in these areas29,30, as shown in Fig. 1. The figure also includes contours of PGA at thresholds of 250 gal, 440 gal, and 800 gal, providing a spatial representation of ground motion intensity. Additionally, two blue circles indicate the central urban areas of the Nansi and Yujing districts, respectively.

Map of the adjacent region affected by the 2025 Dapu earthquake, including seismic intensity distribution and delineation of the study area. The map was generated using the Python plotting libraries matplotlib and mpl_toolkits (version 3.12.10; python.org). The background layer incorporates a satellite image and administrative boundaries obtained from DATA.GOV.TW, an open-access governmental data repository.

Mobile network data description

This study employs mobile network data, capturing active connections between mobile phones and cellular towers, as a proxy for population density. The methodology for estimating population distribution using such data follows the approach outlined by Yeh et al.12 and comprises three main stages. First, the study area is partitioned into a grid system, with each cell representing a square geographical unit. The locations of mobile users are inferred from Charging Data Records31 or Mobility Management Entity data32. Second, the identified user locations are mapped onto the grid, thereby creating a structured spatial representation of population distribution. Finally, the number of active mobile users within each grid cell is aggregated to estimate population density. The accuracy of these estimates is influenced by the spatial density of cellular towers or routers, as network coverage directly affects the completeness and resolution of the data.

The data utilized in this study is derived from Cellular-based Vehicle Probe (CVP) positioning, a real-time population tracking method provided by a major telecommunications operator in Taiwan. The monitored region, located in southern Taiwan, encompasses Chiayi city, Chiayi county, Tainan city, and Kaohsiung city, and is partitioned into square grids measuring 500 m × 500 m. Usable data are available only for grids exhibiting sufficient mobile network activity, resulting in a spatially discontinuous coverage of the population. The analysis focuses on the period leading up to the Dapu earthquake. Specifically, the dataset spans a 4-h window from 23:00 on January 20 to 03:00 on January 21, 2025 (local time), with population counts recorded at 10-min intervals.

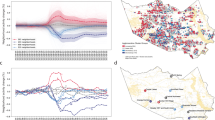

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the population data within individual grid cells surrounding the Nansi and Yujing urban areas exhibit notable changes between 23:00 on January 20 and 03:00 on January 21 (local time). Prior to the Dapu earthquake, population levels within these grids remained relatively stable. However, following the seismic event, a temporal shift in population distribution becomes evident. Some areas experienced an increase in population relative to pre-earthquake conditions, while others showed a marked decrease. This spatial heterogeneity indicates a redistribution of population within the urban region, likely as a direct response to the earthquake.

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of population at 00:10 local time on January 21, 2025, shortly before the occurrence of the Dapu earthquake within the study area. The colored squares represent 500 m × 500 m grid cells, which serve as the statistical units for aggregating population data derived from mobile network signals. The discontinuous distribution of grid cells is attributable to the heterogeneous characteristics of the study area, which encompasses urban, rural, and mountainous regions. The total number of grid cell is 835 across the study area. Warm colors indicate areas of high population density, whereas cool colors represent areas of low density. Notably, the western portion of the study area contains a higher concentration of grid cells, indicating a denser and more centralized population. In contrast, the eastern region exhibits a sparser grid distribution, reflecting lower population density and a more heterogeneous spatial pattern.

Analytical framework

The data used in this study capture population variations as discrete events occurring at specific geographic locations over time. At each time step, the spatial distribution of these events can be effectively modeled using functions that integrate two key dimensions: spatial location and temporal progression. Visualization techniques are employed to address this spatiotemporal modeling challenge. For instant, 3-dimensional icons rendered with colors are placed on geo-maps representing the dependency on temporal data33. Space-time-cube visualizations provide understanding patterns in event data that has both spatial and temporal components for the datasets34,35. Nakaya and Yano36 demonstrated the effectiveness of combining space-time kernel density estimation with volume rendering to explore patterns in spatiotemporal event data. Nevertheless, pinpointing the temporal and spatial specifics of individual events remains challenging within the above-mentioned frameworks. This complexity is amplified when analyzing datasets with dense event occurrences and intricate temporal structures.

An alternative approach involves applying flow analysis to infer spatiotemporal movement patterns from statistical datasets lacking explicit trajectory information. The resulting population dynamics are represented as a vector field, which delineates directional movement. The analysis pipeline comprises two key steps designed to extract this vector field. The first step is converting the spatial discrete data into a continuous distribution over the study area. In general, the method leverages kernel density estimation (KDE) to create a continuous representation of population. KDE-generated density surfaces can be employed as input layers for spatial analysis through map algebra operations37. The second one is to utilize a gravity-like model to estimate potential flows in terms of divergence and convergence within spatiotemporal data. This approach enables us to extract diverging (spreading) and converging (gathering) flow trends, offering insights into patterns like migration shifts. The analytical steps implemented are detailed in the following sections.

Continuous representation of data

Spatiotemporal events are commonly represented using kernel density estimation (KDE), which transforms discrete observations into a continuous probability surface, facilitating the identification of spatial patterns38,39. The KDE is defined as:

where \(\:\widehat{f}\left(x,y\right)\) denotes the estimated density at coordinate \(\:\left(x,y\right)\), \(\:M\) is the number of observations, \(\:{h}_{i}\) is the adaptive bandwidth for each observation, and \(\:K(\cdot\:)\) is the smoothing kernel.

The selection of the kernel function plays a pivotal role in determining both the smoothing characteristics and the structural integrity of the resulting density surface. Gaussian kernels, characterized by their infinite support, promote gradual transitions and globally smooth contours across the spatial domain. This behavior is advantageous for modeling continuous phenomena but may inadvertently suppress fine-scale spatial heterogeneity, leading to potential over-smoothing of localized features38. Conversely, kernels with compact support, such as the Epanechnikov kernel, limit the influence of each observation to a bounded region, thereby preserving sharp spatial boundaries and enhancing interpretability in contexts where delineation of localized clusters is essential. Moreover, compact-support kernels often confer computational benefits due to their reduced processing demands, making them particularly attractive for large-scale or real-time applications40. The Epanechnikov kernel, given by

strikes a balance between smoothness and local sensitivity. The indicator function \(\:\mathbb{I}(\cdot\:)\) ensures the kernel operates within the range \(\:\left|u\right|\le\:1\).

The density estimation is designed to highlight regions with a high concentration of events as areas of influence. Considering that each grid cell represents a statistical unit of 500 m × 500 m, the bandwidth parameter \(\:h\) is set to 1500 m, corresponding to three times the grid side length. The study area is divided into 41 and 39 intervals along the longitudinal and latitudinal axes, respectively, resulting in a total of 1599 nodes. This configuration achieves a balanced level of smoothing in the generated density surface, while preserving sufficient spatial resolution to capture the original distribution patterns at the grid level.

Modified gravity model for spatiotemporal data

Building on the concept of spatial interaction from classical geography, a modified gravity model is used to infer movement tendencies from spatial density distributions41,42. This approach posits that regions with higher event density exert stronger attractive forces on surrounding areas, influencing movement trends.

The interaction between two spatial points \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1}\right)\) and \(\:\left({x}_{2},{y}_{2}\right)\) is modeled as:

where \(\:f\left(x,y\right)\) is the estimated density at a location, \(\:d(\cdot\:)\)is the Euclidean distance between two locations, and \(\:\alpha\:\), \(\:\beta\:\), and \(\:\gamma\:\) are tunable parameters influencing the flow dynamics. In this study, the parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are both set to 1 to assign equal weighting to origin and destination densities, while \(\:\gamma\:\) is set to 2, consistent with the standard formulation of the gravity model. This approach mirrors the classical spatial gravity model but incorporates empirically derived densities from KDE, enabling a dynamic representation of potential movement influenced by spatial heterogeneity.

Flow map extraction model

Flow maps are widely recognized as an effective means of visualizing spatial interactions, particularly when working with large-scale datasets that capture extensive movement or connectivity patterns across geographic regions43,44. They offer an intuitive and interpretable approach to exploring complex spatial dynamics. By condensing vast amounts of interaction data into visually accessible formats, flow maps are especially valuable for analyzing temporal trends and revealing underlying patterns in spatiotemporal processes.

To analyze spatiotemporal flow dynamics, a three-dimensional gravity-based kernel is applied across spatial and temporal dimensions. This flow-extraction model of enables the estimation of flow direction and magnitude by detecting gradients in density across consecutive time steps. The model is computed as:

where \(\:W\) and \(\:T\) define the kernel sizes in the spatial and temporal dimensions, respectively. In the above equation, \(\:G(\cdot\:)\) denotes the gravitational influence between the location \(\:(x,\:y)\) across the time frames—past, present, and future—and its neighboring grids, with the direction and magnitude determined by local density and spatial distance. The summation evaluates gravitational interactions over a local spatiotemporal neighborhood to derive vector fields that reflect movement tendencies. The tuple \(\:(m,n,\tau\:)\) serves as an index referencing the values used in the computation that produces the directional vector, which characterizes the flow orientation in the resulting flow map. As show in Fig. 4, the example demonstrates flow extraction using a kernel with a spatial extent of 2 and a temporal extent of 1. In the middle panel, a red arrow glyph denotes the inferred flow direction extracted from the spatial density changes across time.

To assess the performance of the proposed extraction model, simulated examples of spatial kernel density estimation (KDE) values with bandwidth parameters \(\:{h}_{i}=2,\:3,\) and \(\:4\), derived from population distributions across different timeframes, are presented in Fig. 5. In this context, \(\:{h}_{i}\) is defined as the grid size, corresponding to the unit length in the simulation data.

For \(\:{h}_{i}=2\), the KDE values at timeframes \(\:\tau\:-1\), \(\:\tau\:\), and \(\:\tau\:+1\) are shown in Fig. 5a,c. The corresponding vector field, obtained through the flow extraction kernel, is displayed in Fig. 5d, where arrow glyphs represent both the direction and magnitude of the inferred flow. Results for \(\:{h}_{i}=3\) are presented in Fig. 5e,h, while those for \(\:{h}_{i}=4\) are shown in Fig. 5i,l.

Visual inspection reveals notable changes in color gradients across designated zones. In Zone I, the color intensity increases progressively from Fig. 5a,c, indicating population convergence over time. In contrast, Zones II and III exhibit fading color patterns, suggesting population divergence. These directional trends are effectively captured in the flow map shown in Fig. 5d.

It is also important to note that Zones IV and V are not readily distinguishable through visual inspection alone. Nevertheless, the proposed extraction model successfully identifies subtle variations in population dynamics, thereby enhancing the detection of flow patterns. This capability is particularly valuable for applications in disaster monitoring and emergency response, where timely recognition of population movement is critical.

Furthermore, the distribution of kernel density becomes progressively smoother as the bandwidth parameter \(\:{h}_{i}\) increases. This smoothing effect directly influences the extraction of directional patterns. When \(\:{h}_{i}=2\), directional flow within high-density regions appears relatively consistent; however, at the transition boundaries between high- and low-density areas, substantial variations in density lead to more divergent directional patterns. By contrast, when \(\:{h}_{i}=3\) or higher (e.g., \(\:{h}_{i}=4\)), the density distribution exhibits greater smoothness, yielding more uniform directional results. Such parameter settings are particularly critical for capturing large-scale flow trends.

To investigate the influence of model parameters on the directional outcomes of population flow, we examined three key parameters of the gravity model: \(\:\alpha\:\), \(\:\beta\:\), and \(\:\gamma\:\). Using the input data shown in Fig. 5e,g, a series of experiments were conducted to evaluate how variations in these parameters affect the flow extraction results.

Figure 6a,b compare three parameter settings: (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\:\beta\:=1,\:\gamma\:=2\), represented by blue directional glyphs), (\(\:\alpha\:=3,\:\beta\:=1,\:\gamma\:=2\), represented by orange glyphs), and (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\:\beta\:=3,\:\gamma\:=2\), represented by red glyphs). The baseline configuration (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\:\beta\:=1,\:\gamma\:=2\)) indicates that the central grid and its neighboring grids exert equal gravitational influence. Increasing the weight of the central grid produces only minor directional changes, whereas increasing the weight of neighboring grids results in pronounced differences, particularly around the periphery of high-density clusters where directional shifts are most evident.

Figure 6c,d illustrate the impact of varying \(\:\gamma\:\). Blue glyphs represent (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\beta\:=1,\gamma\:=1\)), orange glyphs represent (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\beta\:=1,\gamma\:=2\)), and red glyphs represent (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\beta\:=1,\gamma\:=3\)). The results reveal only minor differences between \(\:\gamma\:=1\)and \(\:\gamma\:=2\); however, when \(\:\gamma\:=3\), the directional variations become considerably more pronounced.

Finally, Fig. 6e,f present tests with three different kernel sizes: \(\:W=1\) (blue glyphs), \(\:W=2\) (orange glyphs), and \(\:W=3\) (red glyphs). Larger \(\:W\) values reduce the number of grids available for computation while simultaneously incorporating more grid data, thereby altering directional outcomes. This effect is most apparent in regions with low density variation, whereas high-density regions exhibit only minor changes.

Figure 7 illustrates the analytic framework, which provides a structured basis for assessing parameter sensitivity and extracting flow patterns. By integrating theoretical assumptions with computational procedures, the framework clarifies how variations in kernel and gravity model parameters influence directional outcomes.

Illustration of flow extraction using a kernel with spatial extent 2 and temporal extent 1. Grayscale intensity represents temporal density variations, with darker shades indicating higher density. Each grid cell displays a tuple indicating the direction along the \(\:m\), \(\:n\), and \(\:\tau\:\) axes. The red arrow glyph denotes the inferred flow direction.

Simulated examples of KDE values across time slots: (a) \(\:\tau\:-1\), (b) \(\:\tau\:\), and (c) \(\:\tau\:+1\) with the bandwidth parameter set to \(\:{h}_{i}=2\). Panel (d) displays the resulting vector field obtained through the flow extraction kernel, where arrow glyphs represent the direction and magnitude of the inferred flow. Panels (e)–(h) depict results obtained with \(\:{h}_{i}=3\), while panels (i)–(l) show those generated with \(\:{h}_{i}=4\).

Illustration of sensitivity analyses of gravity model parameters. Panels (a,b) compare directional outcomes under varying \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) values. Panels (c,d) highlight the effect of parameter \(\:\gamma\:\), where differences become more evident at \(\:\gamma\:=3\). Panels (e,f) examine different kernel sizes \(\:W\).

Results

Pre-disaster baseline movement patterns

The selection of an appropriate kernel scale must be carefully considered based on the type and resolution of information required for analysis. Utilizing a small kernel bandwidth enables the extraction of detailed or early-stage flow patterns; however, when applied across broad spatial or temporal extents, such fine-scale representations may produce fragmented results that hinder the identification of dominant movement trends. Conversely, employing larger spatial and temporal kernels can effectively highlight general patterns but may obscure localized variations and finer features21. Accordingly, the determination of suitable spatial and temporal kernel parameters is a crucial methodological consideration in flow pattern analysis.

In this study, the KDE method is employed to smooth discrete spatial data. The smoothing parameter ℎ is set to three times the grid cell size to convert irregular, point-based observations into a continuous density surface. This approach moderates abrupt variations between adjacent grid cells, enhancing the interpretability of flow structures. To maintain fine-scale fluid dynamic features while ensuring computational tractability, the spatial kernel width and temporal kernel length were configured to their minimum allowable values. This parameterization achieves an optimal balance between localized sensitivity and the stability of the resulting model estimations.

Flow maps are generated based on mobile network data segmented into 10-minute intervals. In total, 22 flow maps were generated, representing the time span between 23:10 on January 20 and 02:50 on January 21, 2025 (local time), capturing detailed spatiotemporal patterns of population movement during the Dapu earthquake response. To capture flow patterns with fine granularity, the kernel sizes for flow extraction are set to \(\:W=1\) and \(\:T=1\), corresponding to the spatial and temporal dimensions, respectively. The decision to retain the initial movement pattern serves to facilitate systematic temporal comparisons. By establishing a consistent baseline, it becomes possible to monitor and assess deviations in population movement over successive intervals. Analyzing flow changes at 10-minute intervals enables the detection of short-term dynamics and transitional behaviors, which are essential for understanding responses to abrupt events or gradual spatiotemporal developments. This methodological approach improves the temporal resolution of the analysis and supports more nuanced interpretations of mobility patterns and their potential drivers.

As shown in Fig. 8, the flow maps illustrate population movement pattern at 00:10 on January 21, 2025 before the occurrence of the Dapu earthquake. The moving direction utilizes the arrow glyphs, in which the blue color represents the flow at 00:10 on January 21 (local time). The length of arrow presents the level of population moving. The high-population density is centralized around the Chiayi city (Fig. 3), resulting in more varied moving directions and amplitudes compared with the those in rural areas (eastern parts of the study area).

Flow changes in response to earthquake

Figure 9 presents the spatial context of two regions located near zones of intense ground shaking, along with the building outlines45 and officially designated shelters46,47,48. Panel (a) highlights the area that experienced severe structural damage, covering the Nansi and Yujing districts. Panel (b) depicts the vicinity of the earthquake epicenter, including the urban core of Dapu township and the surrounding Zengwen Reservoir region.

Noticeable shifts in population movement were observed following the earthquake, indicating an immediate behavioral response to the seismic event. Prior to the earthquake, mobility patterns were characterized by outward divergence from both urban centers, forming centrifugal flow structures as shown by the blue arrow glyphs. After the event, this trend reversed, with flows converging toward central locations—such as areas of high building density and officially designated shelters— suggesting a behavioral transition associated with homeward movement or emergency coordination. A similar convergence pattern was evident in the urban area of Dapu township (Fig. 9b), whereas peripheral and sparsely populated regions exhibited minimal changes. This contrast indicates that the influence of the earthquake on human mobility was spatially uneven, with more pronounced disruptions in densely populated or structurally impacted areas. In this case, numerous buildings in urban areas were damaged by the earthquake27, leading to changes in human mobility behavior. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings reported by Yeh et al.12.

These findings highlight the spatial heterogeneity of mobility responses to seismic events, emphasizing the importance of distinguishing between urban and rural areas when evaluating post-disaster population dynamics. Urban regions, characterized by higher population densities and complex infrastructure, often exhibit different movement patterns compared to rural areas with dispersed settlements and limited access. As such, spatially differentiated approaches are essential for accurately assessing impacts and informing effective disaster response and recovery strategies.

To quantitatively assess these changes, a grid-based analysis was performed using the KDE method in conjunction with the flow extraction model. The study area was partitioned into 1433 spatial grids across 22 temporal frames, with the earliest time frame designated as the baseline for detecting deviations in population flow. By comparing the directional vectors of each subsequent frame to this reference, the magnitude and spatial extent of movement changes over time were systematically quantified.

Figure 10 displays the number of grids exhibiting directional shifts exceeding angular thresholds of 10°, 30°, 60°, and 90°, referred to as anomalous grids, indicating that population flow deviates from its previous direction. These represent significant deviations in flow direction indicative of behavioral disruption. The earthquake occurrence time is marked by a vertical dashed line. Before the event, the number of anomalous grids remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 300 and 400. Following the earthquake, however, a sharp increase was recorded, with nearly 500 anomalous grids at 00:20 and a peak at 00:30. The number of anomalies gradually declined thereafter, returning to baseline levels by approximately 02:00. This temporal trend suggests short-term but intense disturbances in mobility, followed by a stabilization period.

A substantial rise in grid cells exhibiting minor angular deviations (less than 30°) was observed following the earthquake, as evidenced by the divergence between the \(\:\varphi\:>10^\circ\:\) (blue) and \(\:\varphi\:>30^\circ\:\) (orange) curves in Fig. 10. This deviation pattern indicates that post-seismic movement was not only frequent but also marked by abrupt directional changes. Such behavior may reflect spontaneous, short-range decisions made by individuals navigating disrupted environments—likely including return trips to safe zones, reorientation away from hazards, and mobility within familiar localities where the impact may have been uneven. These findings suggest a spatially heterogeneous response shaped by individual perceptions and contextual adaptations in the immediate aftermath of the seismic event.

To further explore the relationship between ground shaking and mobility responses, we examined the temporal variation of anomalous grids (\(\:\varphi\:>10^\circ\:\)) across different seismic intensity zones, as defined in Fig. 1. The study area was stratified into three Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) categories: PGA ≥ 800 gal, 800 > PGA ≥ 440 gal, and 440 > PGA ≥ 250 gal. To account for the different spatial extents of each zone, the proportion of anomalous grids was calculated relative to the total number of grids within each intensity class.

Figure 11 illustrates the time series of anomalous grid proportions across these seismic intensity zones. A marked post-earthquake increase in anomalies was observed in all zones, with the most significant rise occurring in the 440 > PGA ≥ 250 gal category. This area predominantly includes densely populated urban regions, suggesting that population density plays a critical role in the scale of mobility disruptions. In contrast, the highest intensity zone (PGA ≥ 800 gal), which encompasses more remote and rural areas, exhibited a delayed peak—approximately one time frame later than the other zones. This lag may reflect a more cautious response in rural populations, who may delay movement until additional information becomes available or conditions stabilize.

These results highlight the heterogeneous spatiotemporal dynamics of human mobility in the aftermath of seismic events, revealing distinct behavioral responses that vary across both geographic regions and temporal phases. Such variability reflects the complex interplay between perceived risk, infrastructure disruption, and local context in shaping population movements. Angular deviation thresholds are intended as heuristic measures to quantify directional changes in mobility rather than as definitive evidence of behavioral disruption. Further validation with behavioral data will be necessary to substantiate such interpretations in the future. Nonetheless, the findings also underscore the value of directional flow analysis as a diagnostic tool for detecting critical zones of behavioral change. This approach offers meaningful insights that can inform emergency planning, optimize resource deployment, and enhance real-time decision-making in disaster management and response operations.

Discussion

This study presents a flow extraction framework grounded in the gravity model and applied to mobile communication data to characterize the spatiotemporal dynamics of population movement and assess their responsiveness to seismic disturbances. The mobile data are spatially aggregated using a uniform grid of 500 m × 500 m, with temporal granularity at 10-minute intervals. Each grid records the number of active mobile users connected to cellular towers. Nevertheless, due to the non-uniform distribution of cellular towers—particularly for remote areas—certain grid cells lack consistent data coverage.

To address this limitation and ensure spatial continuity, KDE is employed to transform the discrete and unevenly distributed mobile data into a continuous population surface. When combined across multiple time intervals, this smoothed dataset enables the extraction of dynamic flow fields that reflect changes in human mobility over space and time.

Directional changes in population flows are indicative of human–environment interactions and are particularly sensitive to disruptive events such as earthquakes. Under such conditions, established mobility patterns may be disrupted, resulting in either the dispersal of populations from affected areas or their convergence toward locations perceived as safe or resource-rich. The results of this study reveal that seismic activity significantly influences human movement patterns, with the most pronounced deviations observed in areas experiencing high ground motion intensity. These effects are most acute within the first hour following the earthquake, corroborating previous findings on short-term behavioral responses to disasters2,4,12. The ability to detect such rapid and localized disturbances in near real time offers critical value for emergency response and situational awareness, particularly in identifying zones of acute directional change or intense aggregation and divergence.

The reliability of flow extraction is closely linked to the selection of appropriate spatial and temporal kernel parameters. Smaller kernel sizes enable high-resolution detection of subtle variations in movement but may introduce visual noise and obscure broader trends. Conversely, larger kernels provide a clearer view of macroscopic flow structures but risk masking localized deviations. For instance, a large temporal kernel may conflate repeated presence within a location across time steps as stationary behavior, thereby misrepresenting actual flow dynamics20. As such, the kernel configuration should be aligned with the intended analytical resolution and the scale of the phenomenon being studied.

Beyond characterizing flow direction and magnitude, flow estimation also enables the detection of spatiotemporal patterns of population concentration and dispersal, offering deeper insights into collective human behavior in response to external stimuli. Such patterns are particularly relevant for identifying areas of convergence that may indicate gathering points, or zones of divergence that signal evacuation or avoidance. Looking forward, the flow vectors derived from this method using fine-grained data—for example, a grid size of 50 m × 50 m or smaller—can be further enhanced by projecting them onto road network geometries, thereby generating movement trajectories that more closely align with the constraints and structure of real-world transportation systems. This integration allows for a more realistic representation of mobility behavior, especially in urban environments where road infrastructure governs movement possibilities. When coupled with advanced visualization techniques—such as streamlines or vector fields—this approach improves the interpretability of complex mobility dynamics. It also offers practical value for real-time monitoring, planning, and decision-making in both routine urban management and emergency response scenarios, where understanding how and where people move is essential for effective intervention.

Lastly, the limitations and applications of the proposed method are discussed. The flow-extraction technique is applied to human mobility data without trajectory information, utilizing continuous temporal records to capture large-scale population movements. A key limitation is that mobile network activity is uneven, particularly in rural or mountainous areas. To mitigate this issue, we emphasize that our analysis reflects relative patterns rather than absolute counts, and results should be interpreted with caution in regions where network coverage is sparse. This uneven distribution may introduce bias toward urban centers while underrepresenting peripheral regions. Such variations can be further analyzed across different disaster categories to investigate mobility characteristics.

The dataset spans only a 4-hour window (23:00–03:00), which allows us to focus on immediate mobility dynamics following the earthquake. However, it may not capture medium- or long-term mobility responses such as delayed evacuations or returns. Future work incorporating longer observation periods would be valuable for understanding extended behavioral responses.

The method is applicable to data from various time periods, including intervals following disaster events (e.g., floods, typhoons). As the approach is data-driven, the availability of reliable data is critically important. In severe disasters where base stations are damaged and unable to operate, such data may be unavailable. These missing data, however, convey additional information, as they manifest as noticeable changes in population density within affected areas. Through flow-extraction techniques, computational results can reveal directional variations, which in turn provide early warning signals and serve as valuable reference information for emergency response decision-makers.

Conclusion

This study presents a flow extraction framework that effectively infers directional human mobility from aggregated, trajectory-free mobile network data. By integrating kernel density estimation with a modified gravity model, the proposed method enables the construction of dynamic vector fields that capture spatial and temporal variations in population movement. Applied to the 2025 Dapu earthquake in southern Taiwan, the framework reveals clear and immediate mobility responses to seismic activity, particularly in urban areas experiencing moderate to strong ground shaking.

The results demonstrate that directional flow patterns—especially anomalous shifts in movement—serve as reliable indicators of population behavior during disasters. The framework’s capacity to detect these patterns without relying on individual-level tracking offers both privacy protection and computational efficiency. Furthermore, the ability to localize changes in flow direction provides critical insights for real-time emergency response and post-disaster assessment.

Overall, this research underscores the potential of combining mobile network data with kernel-based flow modeling to enhance disaster monitoring and urban resilience strategies. Future work may expand upon this framework by incorporating road network constraints, real-time data streams, and visual analytics to further support operational decision-making during hazard events.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, Q. & Taylor, J. E. Quantifying human mobility perturbation and resilience in hurricane sandy. PLoS One. 9 (11), e112608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112608 (2014).

Han, S. Y., Tsou, M. H., Knaap, E., Rey, S. & Cao, G. How do cities flow in an emergency? Tracing human mobility patterns during a natural disaster with big data and geospatial data. Sci. Urban Sci. 3, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020051( (2019).

Yabe, T., Sekimoto, Y., Tsubouchi, K. & Ikemoto, S. Cross-comparative analysis of evacuation behavior after earthquakes using mobile phone data. PLoS One. 14 (2), e0211375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211375 (2019).

Bagrow, J. P., Wang, D. & Barabási, A. L. Collective response of human populations to Large-Scale emergencies. PLoS One. 6 (3), e17680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017680 (2011).

Chen, Z., Gong, Z., Yang, S., Ma, Q. & Kan, C. Impact of extreme weather events on urban human flow: A perspective from location-based service data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2020.101520 (2020).

Wei, B., Nie, G., Su, G. & Guo, X. Risk assessment of people trapped in earthquake disasters based on a single building: A case study in Xichang City, Sichuan Province, China. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 13 (1), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2021.2017358 (2022).

Brockmann, D., Hufnagel, L. & Geisel, T. The scaling law of human travel. Nature. 439 (7075), 462–465 (2006).

Song, C., Qu, Z., Blumm, N. & Barabási, A. Limits of predictability in human mobility. Sci. 327(5968), 1018–1021 (2010).

Palchykov, V., Mitrović, M., Jo, H. H., Saramäki, J. & Pan, R. K. Inferring human mobility using communication patterns: implications for disaster management. Sci. Rep. 4, 6174. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06174 (2014).

Phithakkitnukoon, S., Smoreda, Z. & Olivier, P. Socio-geography of human mobility: A study using longitudinal mobile phone data. PLoS One. 6, e39253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039253 (2012).

Giardini, F. et al. Using mobile phone data to map evacuation and displacement: a case study of the central Italy earthquake. Sci. Rep. 13, 22228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48130-4 (2023).

Yeh, E. H., Lin, P. & Huang, M. W. Anomaly detection for population distribution in geo-space using mobile networks data. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2022.3184072 (2022).

Tsou, M. H. Research challenges and opportunities in mapping social media and big data. Cartogr. Geogr. Inform. Sci. 42(sup1), 70–74 (2015).

Han, S. Y., Tsou, M. H. & Clarke, K. C. Do global cities enable global views? Using Twitter to quantify the level of geographical awareness of US cities. PLoS One. 10 (7), e0132464 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Measuring global multi-scale place connectivity using geotagged social media data. Sci. Rep. 11, 14694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94300-7 (2021).

Pappalardo, L. et al. Returners and explorers dichotomy in human mobility. Nat. Commun. 6, 8166. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9166 (2015).

Zhao, C., Zeng, A. & Yeung, C. H. Characteristics of human mobility patterns revealed by high-frequency cell-phone position data. EPJ Data Sci. 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-021-00261-2 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Fine-grained prediction of urban population using mobile phone location data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 32, 9, 1770–1786 (2018).

Shekhar, S., Evans, M. R., Kang, J. M. & Mohan, P. Identifying patterns in spatial information: A survey of methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1(3), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.25 (2011).

Kim, S. et al. Data flow analysis and visualization for spatiotemporal statistical data without trajectory information. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 24(3), 1287–1300. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2017.2666146 (2018).

Lin, B. C. & Chan, T. C. Visualizing population mobility from spatiotemporally aggregated mobile phone data via a 3D gradient approach. Trans. GIS. 00 (0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/tgis.13008 (2022).

Hsu, Y. J., Simons, M., Yu, S. B., Kuo, L. C. & Chen, H. Y. A two-dimensional dislocation model for interseismic deformation of the Taiwan mountain belt. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 211 (3–4), 287–294 (2003).

Yu, S. B., Chen, H. Y. & Kuo, L. C. Velocity field of GPS stations in the Taiwan area. Tectonophysics 274 (1–3), 41–59 (1997).

Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. Broadband array in Taiwan for seismology. Other/Seismic Netw. https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/TW (1996).

Das, R., Sharma, M. L., Wason, H. R., Choudhury, D. & Gonzalez, G. A seismic moment magnitude scale. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 109 (4), 1542–1555. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120180338 (2019).

Das, R. & Das, A. Limitations of Mw and M scales: compelling evidence advocating for the Das magnitude scale (Mwg)—A critical review and analysis. Indian Geotech. J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40098-024-01147-6 (2025).

Su, C. M., Wen, Y. Y. & Chen, C. T. Fast report: strong-motion characteristics of 2025 ML 6.4 Dapu earthquake, Taiwan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 36, 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44195-025-00094-w (2025).

Lu, C. H. et al. Fast report: the 2025 M6.4 Dapu earthquake: preliminary field observation and surface deformation analysis. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 36, 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44195-025-00099-5 (2025).

Wu, Y. M. et al. Performance of the P-alert real-time shakemaps system and onsite warning during the 2025 ML6.4 Dapu earthquake. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 36, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44195-025-00086-w (2025).

GSSMA. https://www.gsmma.gov.tw/uploads/1740358010170OpEOa8lc.pdf (2025). (accessed 17 June 2025).

Telecommunication management. Charging management; Charging architecture and principles, 3GPP TS 32.240, Rev. 16.1.0, [Online]. (2019). https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=1896

General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) enhancements for Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access. Network (E UTRAN) access, 3GPP TS 23.401, Rev. 17.1.0, [Online]. (2021). https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=849

Tominski, C., Schulze-Wollgast, P. & Schumann, H. 3D information visualization for time dependent data on maps. Proc. Int. Conf. Inf. Vis. 175–181 (2005).

Kraak, M. J. & Madzudzo, P. F. Space time visualization for epidemiological research. In ICC : Proceedings of the 23nd International Cartographic Conference ICC: Cartography for Everyone and for You International Cartographic Association (2007).

Bach, B., Dragicevic, P., Archambault, D., Hurter, C. & Carpendale, S. A review of temporal data visualizations based on space-time cube operations. In Eurographics Conference on Visualization (EuroVis)-STAR: State of the Art Report (eds. Borgo, R., Maciejewski, R. & Viola, I.) (The Eurographics Association, 2014).

Nakaya, T. & Yano, K. Visualising crime clusters in a spacetime cube: an exploratory data-analysis approach using spacetime kernel density estimation and scan statistics. Trans. GIS. 14 (3), 223–239 (2010).

Tsou, M. H. et al. Mapping social activities and concepts with social media (Twitter) and web search engines (Yahoo and Bing): a case study in 2012 US presidential election. Cartography Geographic Inform. Sci. 40 (4), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2013.799738 (2013).

Silverman, B. W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. (Chapman Hall, 1986).

Gatrell, A. C. & Bailey, T. C. Interactive spatial data analysis in medical geography. Soc. Sci. Med. 42(6), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00183-2 (1996).

Chacón, J. E. & Duong, T. Multivariate Kernel Smoothing and Its Applications (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018).

Erlander, S. & Stewart, N. F. The gravity model in transportation analysis: Theory and Extensions. VSP (1990).

Martinez, O., Garcia, J. M. & Kumar, N. The gravity model as a tool for decision making. Some highlights for Indian roads. Transp. Res. Proc. 58, 333–339 (2021).

Guo, D. Flow mapping and multivariate visualization of large spatial interaction data. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 15 (6), 1041–1048 (2009).

Andrienko, G. et al. Space, time and visual analytics. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24 (10), 1577–1600 (2010).

Building outlines. refer to (2025). https://3dmaps.nlsc.gov.tw/ (accessed 1 Dec 2025).

Officially designated shelters in Yujing District. Tainan city (2025). https://www.yujing.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=20778&s=8756480 (accessed 1 Dec 2025).

Officially designated shelters in Nansi District. Tainan city (2025). https://nansi.tainan.gov.tw/News.aspx?n=7652&sms=11170 (accessed 1 Dec 2025).

Officially designated shelters in Dapu Township & County, C. https://dapu.cyhg.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=9804&s=1234446 (2025). (accessed 1 Dec 2025).

Funding

This work was supported by National Science and Technology Council (Grant No. NSTC 114-3114-Y-865-001). The financial contributions are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W.H.: Writing draft, calculations, visualization; C.Y.L., M.C.K.: Data pre-processing; W.S.L., T.Y.C.: review, editing; all authors participated in discussions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, MW., Lin, CY., Ke, MC. et al. Analysis of human flow during a natural disaster utilizing trajectory-free mobile network data: a case study of earthquake. Sci Rep 16, 5275 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36255-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36255-1