Abstract

Focusing on the engineering challenge of complex and unpredictable interfacial impact load transfer during the penetration process of a certain type of bomb, this study integrates hammer impact testing and finite element simulation methods to quantitatively analyse the dynamic response characteristics at the nose section/projectile and projectile/base section interfaces. The input and output responses of the interfaces under impact loads were obtained through hammer tests, revealing the variation patterns of peak load and stress during interfacial transfer. Based on Matlab model identification tools, an equivalent transfer model for interfacial loads was established, enabling effective prediction of peak load and pulse width changes during load propagation. The prediction error of the numerical model is less than 15%, meeting engineering accuracy requirements. The research findings provide direct data support and a modeling basis for enhancing the performance of weapon systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the continuous increase in projectile penetration velocity1,2 and the growing structural complexity of targets3 have led to a significant enhancement of mechanical loads experienced by the projectile during penetration. These loads not only exhibit increased amplitude but also notable changes in frequency composition—specifically, a marked rise in the amplitude of high-frequency components. This results in intense transient fluctuations in the time domain and complex spectral characteristics in the frequency domain, featuring a broad bandwidth and multiple peaks. Such loads are typically composed of a strong shock wave generated during the initial collision phase of penetration and the substantial inertial forces arising from projectile deceleration in the mid-to-late stages of penetration. These two components can overlap and couple in the time domain, further complicating load analysis.

During the initial penetration stage, the high-amplitude, short-duration shock wave produced upon impact propagates inward through the projectile structure. This portion of the load, particularly the high-frequency energy during shock wave propagation, is transmitted through mechanical connection interfaces (such as threads, flanges, and bolts) between the projectile body and the fuze system. The interface between the fuze and the projectile is not an ideal rigid connection but a complex boundary exhibiting contact nonlinearity, material nonlinearity, and even geometric nonlinearity4,5,6,7. The properties of this interface significantly alter the propagation of stress waves, manifesting as reflection, transmission, scattering, and energy dissipation of the incident stress wave. Consequently, the waveform, amplitude, and spectral characteristics of the original load signal are modified.

This nonlinear connection interface alters the original load signal transmitted to the interior of the fuze and outputs a mechanical response with distinct characteristics. This transformation process directly affects the actual environment perceived by inertial-sensitive components within the fuze (e.g., accelerometers and spring-mass systems), potentially interfering with the accuracy and reliability of their threshold criteria. This may lead to erroneous judgment of firing conditions by the fuze, ultimately affecting the terminal damage effectiveness of penetrating explosive munitions.

In complex projectile-fuze structures comprising multiple materials and components, stress waves undergo intricate reflection and refraction at interfaces between different materials (such as high-strength steel projectile bodies, aluminum alloy fuze housings, gaskets, and rubber seals). As a result, the transmission behavior of impact loads across these interfaces becomes extremely complex and difficult to describe with simple theoretical models. Similarly, the mapping relationship between the load applied at the projectile surface or connection interface and the mechanical response at critical internal locations (e.g., the firing control module) becomes highly nonlinear and uncertain8,9.

Specifically regarding mechanical connection methods in projectile-fuze systems, bolted connections and their associated gaskets are common and critical. Factors such as bolt preload, contact conditions of threaded engagements, material and thickness of gaskets, and surface roughness of mating faces exhibit considerable diversity and randomness. This leads to complex propagation paths and energy attenuation behavior of stress waves across projectile-fuze interfaces10,11,12. Furthermore, attempting to model threaded connections with detailed three-dimensional geometry in simulation software such as finite element analysis inevitably generates a vast number of elements and nodes, drastically increasing computational scale and significantly reducing numerical simulation efficiency. This poses substantial computational cost challenges for analyzing fuze responses under full-trajectory, multi-condition penetration loads.

To address the engineering challenge of complex impact load transmission and unpredictable responses at connection interfaces (e.g., between the projectile body, forward compartment, and aft compartment) during the penetration of multi-layer hard targets by a certain type of bomb, a systematic research approach combining experimental measurement and numerical simulation is necessary. Establishing a theoretical transfer function model for the projectile and conducting finite element numerical simulations can reveal how interface structures affect stress wave attenuation, reflection, and frequency response characteristics. This will clarify load transmission paths and response behavior, thereby providing reliable theoretical support and design guidance for optimizing fuze system design and achieving accurate firing control in complex penetration environments.

A modified split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) setup was used to perform forward loading tests on projectiles, examining load transfer characteristics under impact. An impact module replaced the traditional striker bar to avoid high-frequency noise from direct metal-on-metal contact. The module consists of a steel block, an aluminum pad, and a high-resilience polyurethane cushion. The steel and aluminum components provide the required kinetic energy, while the polyurethane layer allows tuning of the incident waveform through material selection and thickness adjustment, thereby reducing stress wave interference from the launcher. By varying the air pressure, the impact velocity can be controlled to produce different loading conditions.

The test projectile has a segmented design. A manganin pressure gauge mounted at the impact end records the actual input load. Accelerometers and strain gauges are installed internally and on the surface to capture acceleration overloads at different locations. Ideally, the impact module diameter should match the diameter of the projectile’s conical head section. This approach isolates the projectile’s structural response from complex projectile-target interactions, enabling clearer study of how segmented projectiles behave under impact.

To complement experimental data, numerical simulations were conducted. The model simplifies the projectile into a segmented structure impacted by the same module, ignoring fine internal details. By assigning different initial velocities to the impact module, structural responses under various loading conditions could be simulated. Overload signals extracted from both tests and simulations at the projectile head served as input conditions to validate a previously developed axial vibration-based dynamic response model and to analyze key controlling parameters.

The transfer function analysis of the projectile-fuze system is a common fundamental technology in fuze design, encompassing issues such as the complexity of specific projectile and fuze structures and assembly, and the diversity of various projectile-fuze structural materials. Both theory and experiments have proven that the overload experienced by the fuze during launch, flight, and target impact is not equivalent to the projectile overload. Their relationship is shown in the following equation:

This equation is mathematically called a convolution integral, or simply convolution. Its simplified representation is:

where \(\:{a}_{1}\left(t\right)\) is the overload experienced by the projectile, \(\:{m}_{1}\) is the projectile mass, \(\:{m}_{2}\) is the fuze mass, \(\:{a}_{2}\left(t\right)\) is the overload experienced by the fuze, \(\:F\left(t\right)\) is the bottom pressure of the projectile, and \(\:h\left(t\right)\) is the response generated by the projectile-fuze system when the excitation is an impulse function, i.e., the impulse response.

The impulse response of the projectile-fuze system and the system’s frequency-domain transfer function form a Fourier transform pair, i.e., \(\:h\left(t\right)\leftrightarrow\:H\left(f\right)\). In the complex frequency domain:

where \(\:{A}_{2}\left(f\right)\) is the Fourier transform of the fuze overload \(\:{a}_{2}\left(t\right)\), \(\:H\left(f\right)\) is the frequency-domain transfer function of the projectile-fuze system, and \(\:F\left(f\right)\) is the Fourier transform of the projectile bottom pressure \(\:F\left(t\right)\). The acceleration response \(\:{a}_{2}\left(t\right)\) at the fuze location in the projectile to the base pressure is the inverse Fourier transform of \(\:{A}_{2}\left(f\right)\).

Currently, there are two main methods13 for calculating the transfer function of the projectile-fuze system: one combines hammer impact test with theoretical analysis, and the other uses finite element analysis software ANSYS for computer-based solutions14,15. The system identification method for the projectile-fuze system transfer function through hammer impact test is a method that measures input excitation and output response to perform system identification and obtain the frequency-domain transfer function. This is achieved by setting up a hammer impact test system. The hammer impact test platform is similar in principle to the improved SHPB apparatus. An impact hammer is used to replace the impact module, and the incident waveform can also be adjusted based on material and thickness.

Therefore, to meet the requirements of efficient computation and accurately reproduce the load transfer mechanism of connection structures, this section establishes model-based test methods and numerical simulations for typical connection structures. Specific typical structures containing connection interfaces (such as projectile-fuze interface) are used as test objects, and the load transfer characteristics during the test process are obtained by combining the hammer impact test platform.

Test

Test principle and apparatus

A strain gage is a sensor that measures the strain of an object by calculating stress from small deformations on the material surface. Its basic principle is to measure strain using the resistance change of the strain gage as it deforms. When the material deforms, the strain gage also deforms, causing its resistance to change.

where ΔR is the resistance change, R is the initial resistance, G is the gage factor of the strain gage, and ε is the strain. By measuring the resistance change, the strain can be calculated, and the stress in the direction of the strain gage can be derived using the following equation:

where \(\:\sigma\:\) is the stress, and \(\:E\) is the elasticity modulus of the material.

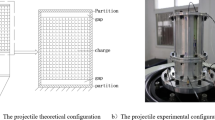

The main equipment used includes the DEWE Soft data acquisition and analysis system, SIRIUS series acquisition modules, sensors, impact hammer, computer, and other hardware. Photos of the main instruments are shown in Fig. 1, and the test schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 2. The scaled-down projectile consists of a nose section, projectile body, and base section, all connected by eight M2 screws, forming two interfaces: nose section/projectile body and projectile body/base section. To study the load transfer mechanism at these two interfaces, strain gages were bonded at three locations (1, 2, 3) on the nose section/projectile body interface and two locations (4, 5) on the projectile body/base section interface to collect stress data. The impact hammer was used to apply impulsive force to the structure, the force sensor measured the impulsive force, and the strain gages measured the strain response of the structure. After obtaining the strain curves of the structure, the stress curves could be derived based on the test principle and the known elasticity modulus of the material.

Test results

Interface stress distribution mechanism

Three independent tests were conducted on the scaled-down projectile using the hammer impact test platform. The input excitations from the impact hammer are shown in Fig. 3. The figure shows that the peak values of the impact hammer’s input excitation increased progressively across the three tests, while the pulse width remained roughly the same at 0.25ms.

To investigate the stress transfer mechanism at the interfaces, channels 1 and 3 were selected to analyze the nose section/projectile body interface, and channels 4 and 5 were selected to analyze the projectile body/base section interface. Channel 2 was excluded because the second strain gage was bonded to the ogive of the projectile body, and the stress direction obtained was along the tangent of that location rather than the axial direction of the scaled-down projectile, making it unsuitable for subsequent analysis. Figure 4 shows the stress-time curves from channels 1, 3, 4, and 5 in the three tests. The figure shows that in all four channels across the three tests, the pulse width of the first compression wave in the stress curves was consistent. The reflected wave pulse width and trends in the first and second tests were basically the same, while the reflected wave pulse width in the third test increased slightly, though the trends remained consistent. Figure 5 shows the relationship between the peak stress and input excitation from the four channels in the three tests. The figure shows a linear relationship between peak stress and input excitation, indicating uniformity in the system.

Figure 6 shows the stress transfer mechanism at the two interfaces in the first test. The figure shows that as the load passed through the nose section/projectile body interface, the stress wave pulse width did not change significantly and gradually increased over time until it disappeared. Similarly, as the load passed through the projectile body/base section interface, the stress wave pulse width did not change significantly and gradually increased over time until it disappeared. It should be noted that the differences in peak stress values among the four channels in the figure are not representative, as the bonding locations of the strain gages in Fig. 2 were somewhat random. If a strain gage happened to be located in a stress concentration area, the measured stress amplitude would increase.

Figures 7 and 8 show the stress transfer mechanism at the two interfaces in the second and third tests, respectively. The figures show that, similar to Fig. 6, as the load passed through the nose section/projectile body interface, the stress wave pulse width did not change significantly and gradually increased over time until it disappeared. Similarly, as the load passed through the projectile body/base section interface, the stress wave pulse width did not change significantly and gradually increased over time until it disappeared.

As can be observed in Figs. 6 and 7, and 8: First, the peaks of the two curves appear at nearly the same position. This is because the propagation speed of stress waves in solids is very high, resulting in almost no noticeable delay. Second, the amplitude decreases, which is attributed to the following reasons: (1) The collision between threaded teeth at the connection interface leads to mutual cancellation of energy during stress wave transmission. (2) Although the energy of the stress wave is conserved during interface transmission, amplitude attenuation occurs due to the reflection of stress waves at the interface. Third, the pulse width changes only slightly. This is because the stress wave excited by the impact hammer contains components of different frequencies. When passing through the threaded connection interface, the interface introduces nearly identical phase delays to each frequency component. As a result, the superposition of these components causes almost no change in the overall pulse width of the stress wave.

It should be noted that the differences in peak stress values among the four channels in the figures are also not representative, as the bonding locations of the strain gages in Fig. 2 were somewhat random. If a strain gage happened to be located in a stress concentration area, the measured stress amplitude would increase.

Interface stress equivalent transfer model

Let the input function of the projectile-fuze system, i.e., the projectile overload, be \(\:u\left(t\right)\), and the output function, i.e., the fuze overload, be \(\:y\left(t\right)\). The transfer function of this system is the quotient of the Laplace transform of \(\:y\left(t\right)\), i.e., \(\:Y\left(s\right)\), and the Laplace transform of \(\:u\left(t\right)\), i.e., \(\:U\left(s\right)\):

The transfer function of different projectiles is uniquely determined and corresponds to the system’s differential equation. It is an inherent property of the system itself, independent of the magnitude and nature of the input.

A typical projectile-fuze system can be simplified into the equivalent system model shown in Fig. 916. Here, \(\:{m}_{1}\), \(\:{m}_{2}\), and \(\:{m}_{3}\) represent the masses of the fuze, fuzing explosive charge, and base cover, respectively; \(\:{k}_{1}\), \(\:{k}_{2}\), \(\:{k}_{3}\), \(\:{k}_{4}\), and \(\:{k}_{5}\) represent the equivalent stiffness coefficients between the projectile body and fuze, fuze and fuzing explosive charge, fuze and base cover, projectile body and fuzing explosive charge, and projectile body and base cover, respectively; \(\:{c}_{1}\), \(\:{c}_{2}\), \(\:{c}_{3}\), \(\:{c}_{4}\), and \(\:{c}_{5}\) represent the equivalent damping coefficients between the projectile body and fuze, fuze and fuzing explosive charge, fuze and base cover, projectile body and fuzing explosive charge, and projectile body and base cover, respectively.

The vibration equation for a multi-degree-of-freedom system is:

The system transfer function is unaffected by external forces. Let \(\:F=0\), substitute the parameters, and obtain:

Perform Laplace transform on the above equation and organize it to obtain:

where \(\:{G}_{1},\:\dots\:,\:{G}_{7}\) are functions of the equivalent masses \(\:{m}_{i}\), equivalent stiffness coefficients \(\:{k}_{i}\), and equivalent damping coefficients \(\:{c}_{i}\). The above equation can be equivalent to a closed-loop transfer function:

Convert the above equation to standard form:

where \(\:{a}_{1},\:\dots\:,\:{a}_{6},\:{b}_{1},\:\dots\:,\:{b}_{6}\) are functions of the equivalent masses \(\:{m}_{i}\), equivalent stiffness coefficients \(\:{k}_{i}\), and equivalent damping coefficients \(\:{c}_{i}\). The numerator of \(\:G\left(s\right)\) is a 5th-order polynomial of \(\:s\), and the denominator is a 6 polynomial of \(\:s\), indicating that the established equivalent model of the projectile-fuze system contains 5 zeros and 6 poles.

When the input and output quantities are known, the transfer function can be obtained using relevant tools. Alternatively, if the transfer function is known, the input quantity can be determined based on the required output quantity. Based on the above properties of the transfer function and the typical projectile-fuze system equivalent model, system identification tools can be used to input the number of zeros and poles and perform parameter identification on the system transfer function to obtain the projectile-fuze system transfer function. This section borrows the concept of transfer function to establish an equivalent transfer model for interface loads. Based on the interface stress distribution, system identification tools are used to obtain the equivalent transfer model17,18,19,20,21,22. Specifically, the stress curves from the four channels of the scaled-down projectile obtained in the hammer impact test are used with the MATLAB system identification tool to perform parameter identification on the 12 parameters of the system transfer function in Eq. (11), obtaining the transfer function for each interface:

Equivalent transfer function for the nose section/projectile body interface (channels 1 and 3) in the first test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.81\right)\):

Equivalent transfer function for the projectile body/base section interface (channels 4 and 5) in the first test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.75\right)\):

Equivalent transfer function for the nose section/projectile body interface (channels 1 and 3) in the second test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.88\right)\):

Equivalent transfer function for the projectile body/base section interface (channels 4 and 5) in the second test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.83\right)\):

Equivalent transfer function for the nose section/projectile body interface (channels 1 and 3) in the third test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.72\right)\):

Equivalent transfer function for the projectile body/base section interface (channels 4 and 5) in the third test \(\:\left({R}^{2}=0.92\right)\):

Figure 10 shows the comparison between the stress curves calculated from the transfer functions in Eqs. (12)-(17) and the hammer impact test curves for channels 3 and 5. The figure shows that the stress curves for the first interface (channel 3) and second interface (channel 5) in all three tests matched well, indicating that the transfer function can accurately reflect the actual response characteristics of the projectile-fuze system under penetration impact.

Comparison between stress curves from transfer function calculation and hammer impact test: (a) first interface (channel 3) in first test, (b) second interface (channel 5) in first test, (c) first interface (channel 3) in second test, (d) second interface (channel 5) in second test, (e) first interface (channel 3) in third test, (f) second interface (channel 5) in third test.

To further analyze the predictive capability of the equivalent transfer model, the coefficient of multiple determination was used to evaluate the agreement between the model predictions and test results. The coefficient of multiple determination is a statistical measure of the fit between the model-predicted curve and the measured curve, reflecting the proportion of the dependent variable \(\:y\)‘s variation that can be explained by the model-predicted curve. It is commonly used to evaluate the goodness of fit of a model. Its expression is:

where \(\:SSE\) is the sum of squared errors, and \(\:SST\) is the total sum of squares, expressed as:

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the measured value, \(\:{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{i}\) is the mean of the measured values, and \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the model-predicted value.

Based on Eq. (18), the coefficient of multiple determination for the equivalent transfer models at each interface in the three tests was calculated, as shown in Table 1. The table shows that the stress curves for the first interface (channel 3) in the second test and the second interface (channel 5) in the third test matched well, indicating that the transfer function can more accurately reflect the actual response characteristics of the projectile-fuze system under penetration impact.

Numerical simulation

Finite element model

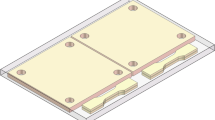

The principle of model simplification is to ensure the accuracy of the simplified model’s calculation results while saving computational resources and improving efficiency. Therefore, some small components (small bolts, pins, spring washers used for connections between components, small holes on components, etc.) can be deleted. Some detailed geometric features (mounting bases, main bodies, etc.) can be appropriately simplified (removing some small local parts, edges, corners, etc., and modifying local topological relationships) while maintaining the overall shape. The main geometric features of the components should be retained to ensure calculation accuracy while reducing the difficulty and quantity of mesh generation and improving computational efficiency. Following these simplification principles, the components were reassembled in the finite element software according to their original connection relationships. The simplified geometric model of the scaled-down projectile is shown in Fig. 11. The figure shows that the penetrating guided bomb consists of a nose section, projectile, and base section. The projectile casing is made of 35CrMnSi, and the other parts are made of aluminum alloy. Using Hypermesh software, all components were divided into mappable states suitable for hexahedral meshing through reasonable topological relationship selection and geometric partitioning. All components were then meshed with hexahedral elements to ensure calculation accuracy (hexahedral meshes are more accurate than tetrahedral meshes). For components that may undergo large plastic deformations, such as the projectile head, finer meshing was applied. For components that undergo elastic deformations and primarily serve as elastic load transfer paths, such as potting glue and main bodies, relatively coarse meshing was used. The specific mesh generation for the overall structure and key typical components is shown in Fig. 12. The nose section, projectile body, and base section all used the strain-rate-dependent Johnson-Cook constitutive model. Bolt connections, which play an important role in load transfer, were modeled using the Elastic model for precise simulation of their load transfer function. In this study, the connections between the nose section and projectile body, as well as between the projectile body and base section, were all fixed connections, defined using the TIE keyword.

Simulation results

Model verification

The numerical simulation model was verified based on the interface load equivalent transfer model established in Sect. 2.2.2. f 12 shows the stress propagation mechanism at different parts of the scaled-down projectile during impact at 50 m/s. Figure 12(a) corresponds to the interface locations selected during the test, Fig. 12(b) axial stress-time at nose section/projectile body interface, and Fig. 12(c) axial stress-time at projectile body/base section interface. The figures show that, similar to the test results, when the load passed through the nose section/projectile body interface and the projectile body/base section interface, the stress wave pulse width did not change significantly and did not gradually increase over time until disappearing. To verify the accuracy of the numerical model, the stress curves for the nose section/projectile body interface (channel 3) and projectile body/base section interface (channel 5) calculated using transfer functions Eqs. (14) and (17) were compared with the numerical results, as shown in Fig. 13. Additionally, the coefficient of multiple determination for each interface equivalent transfer model was calculated using Eq. (18), yielding results of 53.63% and 60%, respectively, indicating poor agreement when using the full curve for calculation.

To further analyze the agreement between the transfer function predictions and numerical results, the peaks and pulse widths of the first compression wave and first tensile wave in the stress curves were selected for comparison. This is because, for structural components, the first compression wave and first tensile wave in the stress curves typically have higher peaks and wider pulse widths, making them more critical. Therefore, from a stringent assessment perspective, selecting the first compression and tensile waves is more meaningful. The corresponding calculation results in time domain are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and results in frequency domain are shown in Table 4. The Tables 2 and 3 show that the errors for both interfaces were less than 15%, meeting the assessment requirement of “the accuracy of the refined numerical model of the bomb based on elastoplastic response is better than 85%” in technical indicator (2).

The frequency-domain curves in Fig. 14 are derived from the time-domain curves in Fig. 13. From Fig. 14, it can be observed that the first three peaks in each graph exhibit high amplitude. The overall trends of the two curves in Figs. 13(a) and (b) are generally consistent, indicating good agreement between the theoretical model and the numerical model. In Table 4, a comparison is made between the maximum values of the first three peaks from the theoretical model and those from the numerical model, corresponding to Figs. 13(a) and (b). The errors associated with the respective peaks are within 15%, which meets engineering requirements.

Interface stress transfer mechanism

Figure 15 shows the stress propagation cloud diagram during the impact of the bomb by the mass block at 50 m/s. Figure 15(a) shows a stress pulse was generated at the head of the nose section at the initial impact moment. Figure 15(b) shows the stress wave propagating to the connection between the nose section and projectile body, where stress concentration occurred at the tail of the nose section due to the interface. Figure 15(c) shows the stress wave propagating to the base section, and Fig. 15(d) shows the stress wave propagating to the projectile body, generating uniformly propagating stress waves inside the projectile body. Figure 16 shows the stress propagation mechanism at different parts of the bomb. Figure 16(a) shows the selected bomb locations, Fig. 16(b) shows the axial stress variation at the head and tail of the nose section over time, Fig. 16(c) shows the axial stress variation at the head and tail of the projectile body over time, and Fig. 16(d) shows the axial stress variation at the head and tail of the base section over time. Figure 16 shows that during the initial impact, the mass block generated an instantaneous stress pulse wave with a peak of 350 MPa and a pulse width of 50 \(\:\mu\:s\) at the head of the nose section, and a sinusoidal stress wave with an amplitude of 100 MPa and a period of 200 \(\:\mu\:s\) at the tail of the nose section. The amplitude of this wave gradually decreased over time. A sinusoidal stress wave with an amplitude of 100 MPa and a period of 200 was also generated at the head of the projectile body, and its amplitude significantly decreased when propagating to the tail of the projectile body. A sinusoidal stress wave with an amplitude of 2 MPa and a period of 200 was generated at the head of the base section, and its amplitude essentially dropped to zero when propagating to the tail of the base section. Additionally, calculations showed that the time for the stress wave to propagate from the head (point C) to the tail (point D) of the projectile body was \(\:t=l/v=\left(23.38cm\right)/0.6(cm/\mu\:s)=38.97\mu\:s\), with a 2.6% error compared to the simulation result of 40 . Figure 17 shows the stress transfer mechanism at the nose section/projectile body interface and projectile body/base section interface. The figure shows that the sinusoidal stress wave at the tail of the nose section (point B) propagated to the head of the projectile body (point C) through the nose section/projectile body interface with almost no attenuation. When propagating to the tail of the projectile body (point D), the stress amplitude decreased to 4 MPa, and further decreased to 2 MPa when propagating to the head of the base section (point E). Additionally, the time-domain curve of the stress wave at the tail of the projectile body shows obvious stress oscillation when the stress wave propagated to this location.

Figure 18 shows the peak stress curves at points B and C of the nose section/projectile body interface and points D and E of the projectile body/base section interface during impact at different velocities (30 m/s, 40 m/s, 50 m/s). The figure shows that as the impact velocity increased, the peak stresses at these four locations generally followed a linear increasing trend, indicating uniformity in the system. More detailed stress variation trends over time at points B and D under different impact velocities are shown in Fig. 19. The figure shows that the stress wave trends under different impact velocities were basically the same, with only differences in peak stresses, further confirming the uniformity of the system.

Conclusion

This report conducted experimental tests and simulation calculations on the interface impact load transfer mechanism of a certain type of bomb. Using the hammer impact test platform and numerical simulation methods, the interface impact load transfer mechanism of the bomb was studied, and an equivalent transfer model for interface loads was established, and the dynamic response mechanism of interfaces during bomb penetration was resolved, which providing technical support for the performance improvement of weapon equipment.

Data availability

The Data is available under permission from Science and Technology on Electromechanical Dynamic Control Laboratory. You can also submit a request for data to the corresponding author.

References

Deng, Z., Chen, Y. & Yu, D. Research on the aerodynamic characteristics of ramjet extended range projectile [J]. Autom. Application. 64 (18), 183–185 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. Overview of developments of precision strike weapons in foreign countries in 2024 [J]. Tactical Missile Technol. 229(01), 33–41 (2025).

Sun, X. et al. Anti-Penetration performance of composite structures with metal-packaged ceramic interlayer and UHMWPE laminate [J]. Materials 16 (6), 2469 (2023).

Xiao, H. Nonlinear Vibration Mechanisms and Energy Dissipation of Contact Interfaces [D] (China; Chongqing University, 2012).

Rigaud, E. & Perret-Liaudet, J. Experiments and numerical results on non-linear vibrations of an impacting Hertzian contact. Part 1: harmonic excitation [J]. J. Sound Vib. 265 (2), 289–307 (2003).

Burlayenko, V. N. & Sadowski, T. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of harmonically excited debonded sandwich plates using finite element modelling [J]. Compos. Struct. 108, 354–366 (2014).

Zheng, Z. et al. Nonlinear dynamic model and response characteristics of penetration Projectile-fuze system [J]. Acta Armamentarii 46(4), 240097 (2025).

Guo, Y. C. et al. Nonlinearity of interfaces and force transmission of bolted flange joints under impact loading [J]. Int. J. Impact Eng. 109, 214–223 (2017).

Liu, Z. Detonation Control Techniques for Penetration Based on the Dynamic Response of projectile-fuze System [D] (China; Beijing Institute of Technology, 2016).

Bretl, J. L. & Cook, R. D. Modelling the load transfer in threaded connections by the finite element method [J]. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 14 (9), 1359–1377 (1979).

Yu, D. et al. Dynamic transfer model and applications of a penetrating projectile-fuze multibody system [J]. Int. J. Mech. Syst. Dynamics. 3 (4), 360–372 (2023).

Zhang, D. M. et al. Study on collision of threaded connection during impact [J]. Int. J. Impact Eng. 106, 133–145 (2017).

Saarakkala, S. E. & Hinkkanen, M. Identification of Two-Mass mechanical systems using torque excitation: design and experimental evaluation [J]. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 51 (5), 4180–4189 (2015).

Nwade, I. S. Obtaining the Transfer Function of a Camera Mount Using ANSYS and MATLAB [D] (United States; University of North Dakota, 2023).

Khot, S. M. & Yelve, N. P. Modeling and response analysis of dynamic systems by using ANSYS© and MATLAB© [J]. J. Vib. Control. 17 (6), 953–958 (2011).

Xu, F., Li, L. & Li, C. Penetration fuze overload equivalent scaled test method [J]. J. Detect. Control. 46 (02), 74–79 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Identification method for transfer function of steam generator level control system of Lingao phase Ⅱ NPP [J]. Nuclear Power Eng. 32 (5), 29–32 (2011).

Chen, S. Model Predictive Control of the HVAC System in Industrial Cleanrooms for Energy Saving [D] (United States; University of Liverpool, 2017).

Arda Ozdemir, A. & Gumussoy, S. Transfer function Estimation in system identification toolbox via vector fitting [J]. Arxiv 50 (1), 6232–6237 (2020).

Chodnicki, M. et al. The mathematical model of UAV vertical take-off and landing [J]. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 91 (2), 249–256 (2019).

Nimawat, D. & Nagar, N. Self-Tuning fuzzy Pid controllers application on industrial hydraulic actuator using unique system identification approach. J 22, 1–6 (2019).

Dokuz, M. E., Gök, K. & Çaşka, S. First steps towards structural utilisation of the Lattice-Structured cantilever beam: system Identification, modal and static structural analysis [J]. Bayburt Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi. 7 (1), 35–46 (2024).

Funding

The authors are thankful for the support from Science and Technology on Electromechanical Dynamic Control Laboratory, China, No. 6142601022303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jia-Chen Hao, Shao-Kang Cui wrote the main manuscript text and prepared experiment. Guang-Song Ma and Yong-Pan Duan gave a support for the experiment.Sen Wang and Peng-Zhao Xu gave a help to prepare figures of this manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, JC., Cui, SK., Ma, GS. et al. Experimental and numerical study on interfacial impact load transfer mechanism. Sci Rep 16, 5282 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36273-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36273-z