Abstract

An efficient siderophore-producing bacterium, Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7, was isolated from the rhizosphere of an inland rice variety cultivated in the underexplored coastal saline-affected rice fields of Kerala, India. The complete genome of Bmkn7 possessed a single circular chromosome of 8,397,732 bp with an average GC content of 66.5%. Phylogenetic and comparative genome studies identified Bmkn7 as a member of the genus Burkholderia, closely related to the plant-associated Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovar I. The antiSMASH analysis identified a rich repertoire of 20 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) involved in the production of diverse specialized secondary metabolites, including non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) encoding siderophores (pyochelin, ornibactin), a pyrrolnitrin-encoding cluster, and terpenes. Furthermore, the presence of several orphan BGCs suggests the potential genetic ability of Bmkn7 to produce novel bioactive compounds. In addition, Bmkn7 exhibited potential antimicrobial activity against various bacterial and fungal phytopathogens involving metabolites dependent and independent of siderophores, including unidentified bioactive molecules. Additionally, Bmkn7 harbors several plant-associated and plant growth-promoting genes, including those involved in phosphate solubilization, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase production, mitigation of plant-derived oxidative stress, and the utilization of various plant-derived substrates. Notably, the Bmkn7 genome lacks key genes associated with animal-host interactions and virulence, suggesting a plant-associated lifestyle. Combining genomic analyses and phenotypic assays, we provide evidence suggesting Bmkn7 as an ideal candidate for phytopathogen suppression and plant growth promotion, further expanding knowledge on plant-associated Burkholderia strains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are key determinants of plant health and productivity1, enabling nutrient acquisition2,3,4, detoxification5, phytohormone production6, stress tolerance7,8,9, and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens10. These functions are mediated by specific genes, such as nif, pho, and acdS for nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and stress ethylene modulation; kat, sod, and gst for oxidative and osmotic stress tolerance. PGPR also deploy a diverse repertoire of bioactive metabolites that contribute to plant growth promotion and pathogen suppression. Among these, siderophores encoded within specialized biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) such as pvd, ent, and pch mediate high-affinity iron sequestration that limits pathogen proliferation while improving plant iron availability, functioning as both biocontrol agents and growth promoters11,12,13. Additional antagonism arises from competition for nutrients and space, production of antimicrobial metabolites, and the activation of induced systemic resistance (ISR)14. ISR is initiated when microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs)—including flagellin, lipopolysaccharides, and extracellular polysaccharides—are recognized by plant pattern-recognition receptors, triggering jasmonic acid and ethylene dependent signaling pathways that prime plants for broad-spectrum defense15. Together, these mechanisms form the core basis for PGPR-mediated disease suppression and plant growth enhancement.

Despite the promising potential of PGPR, pathogens develop diverse countermeasures, including repression of biosynthetic genes involved in biocontrol, detoxification,antibiotic resistance, and active efflux of antibiotics16. For instance, as part of the pathogen defense mechanism, one of the well-known microbial defense compounds, the siderophore pyochelin17, has been modified to reduce its antifungal activity by Phellinus noxius9. Such dynamic competitive interplay between pathogens and PGPR underscores the need to exploit more effective plant protection strategies for sustainable agriculture, including isolating PGPR strains that produce novel antimicrobial compounds. Consequently, searching for novel or highly potent PGPR strains has led to exploring less-studied environments that may yield such microbes.

Accordingly, in this study, we focused on plant-associated rhizobacteria from locally adapted rice cultivars traditionally grown in the salinity-prone coastal regions of Kerala, a niche that remains largely unexplored. To fill the gap, microbes isolated from rice plants cultivated in these areas were screened for potential siderophilic PGPR capable of exhibiting dual functions of plant growth promotion and antifungal activity18 using a modified Chrome Azurol S (CAS) assay19. Such isolated strains may offer unique bioactive metabolites that confer pathogen resistance and promote plant growth, contributing to sustainable crop protection and development20,21. The promising strain obtained was phylogenetically related to the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) and designated as Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 (Bmkn7).

The Burkholderia genus, comprising over 100 species, has gained increasing recognition as an effective plant PGPR, with scientific interest resurging in 2010 due to its robust antimicrobial properties, diverse siderophore production, and expanding genome data that enabled refined taxonomic classification22. While certain members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) are known opportunistic human pathogens and others are phytopathogenic, most Burkholderia species exhibit neutral or beneficial interactions with plants23. The plant-associated Burkholderia species exhibit diverse plant-beneficial traits, including plant growth promotion, bioremediation, and biological control activities24. Among them, several species, such as B. ambifaria, B. anthina, B. contaminans, B. gladioli, and B. pyrrocinia, are well characterized for their antifungal activity25, underscoring their potential role in sustainable agriculture. Despite being categorized as opportunistic pathogens26, the genomovar I of the Bcc comprises diverse strains with plant growth promotion traits27. Large, multipartite genomes distinguish Burkholderia species and exhibit exceptional ecological and metabolic versatility. Their genomic plasticity supports an extensive array of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), many of which are responsible for producing structurally diverse and bioactive secondary metabolites with therapeutic and agricultural relevance. Unlike classical polyketide synthase (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) systems, many Burkholderia species encode novel biosynthetic pathways with unique structural features28. All these attributes have prompted the exploration of this taxon to discover novel compounds.

In this study, we investigated the potential of Bmkn7 phenotypically and genotypically for its antimicrobial and plant growth-promoting functions, and our findings contribute to the growing interest in identifying underexplored PGPR strains with unique bioactive compounds. Exploring Burkholderia as a reservoir of bioactive compounds enhances our understanding of plant-microbe interactions and highlights its potential for promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Materials and methods

Isolation and screening of siderophore-producing cultures

The strains were isolated from the soil, bulk soil, rhizosphere, and roots of different saline-tolerant rice varieties collected from agricultural fields near the coastal belt of Kerala, India (9°52’06.4"N 76°16’58.3"E, 9°50’25.3"N 76°16’51.5"E, 10°04’42.5"N 76°15’20.9"E, 12°01’36.1"N 75°17’28.9"E,12°09’37.8"N 75°12’54.6"E). Isolation was carried out using the conventional serial dilution technique29 using different media (Table S1). Distinct colonies exhibiting variations in size and morphology were selected from the isolation plates and subsequently streaked onto Nutrient Agar (NA) plates supplemented with an additional 0.5% NaCl to obtain pure strains.

Referring to the method of blue agar CAS assay19, we screened for the siderophore-producing bacterial strains from the isolated pools. Among these, the strain designated as Bmkn7 was shortlisted for further study.

Bmkn7 was isolated from the rhizosphere of the rice variety Aiswarya grown in a saline-affected area using Basal Mineral Media (Hi-Media - M1588) at 0.153% (w/v), supplemented with the following components (g L⁻¹): yeast extract, 0.5; peptone, 0.5; xylose, 1; arabinose, 1; and rhamnose, 1. To maintain the culture at 4 °C and for subculturing, Reasoner’s 2 A (R2A) agar (HiMedia - SMEB962D), supplemented with 0.5% NaCl (R2AN), was used. Bacterial cells were preserved at − 80 °C in 20% (v/v) glycerol suspensions prepared from freshly grown cultures for long-term storage.

DNA extraction and genome sequencing

The high-quality genomic DNA of Bmkn7 was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole genome sequencing was conducted using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform, with paired-end reads, and the Nanopore GridION X5 platform at Genotypic Technology Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru, India. The Illumina raw reads were processed and trimmed based on a quality score of 30 and a minimum read length of 20 using Trim Galore v0.4.0, and adapter sequences were removed from the Nanopore raw reads using Porechop v0.2.4. The hybrid genome assembly was carried out using MaSuRCA v3.3.730 and CheckM analysis (v1.2.3)31 to determine the contamination and completeness of the Bmkn7 genome. The obtained genome sequence was annotated using the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) v.432 and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP)34.

Data Availability

The whole genome sequence of Bmkn7 was deposited in NCBI with accession number JBGCUH000000000.

Genomic characteristics, phylogenetic, and comparative analysis of Bmkn7

Proksee33 was used to visualize genomic features, such as coding sequences, RNA genes, GC content, and GC skew, enabling the construction of a circular genome map of Bmkn7 using PGAP-derived annotations. The RAST-based subsystem feature analysis identified multiple genes and gene clusters within the Bmkn7 genome, which were classified into various functional gene categories. IslandViewer 435 was also used to predict the genomic islands (GIs).

Further, phylogenetic analysis of the Bmkn7 genome was conducted using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach using the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS)36. Intergenomic distances were calculated using the GBDP distance formula d5 with the “Greedy-with-Trimming” algorithm, and branch support values were inferred from 100 pseudo-bootstrap replicates. The tree was constructed with FastME v2.1.6.1 under the balanced minimum evolution criterion. For a comprehensive comparison of the Bmkn7 genome with related Burkholderia strains (Burkholderia cepacia BRDJ, Burkholderia reimsis BE51, Burkholderia sp. AU4i, Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416, and Burkholderiacepacia ATCC 25416 strain UCB 717), measures of similarity based on average amino acid identity (AAI), average nucleotide identity (ANI), and digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) values were calculated using JSpeciesWS37, Kostas lab38, and Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator 4.0 (GGDC)39, respectively.

The orthologous cluster analysis and protein similarity comparisons were also performed using the OrthoVenn3 web server40 based on conserved coding sequences (CDSs). Default parameters were applied, with an e-value cut-off of 1e-5 for protein similarity and an inflation value of 1.5 for orthologous cluster generation.

PLaBAse (https://plabase.cs.uni-tuebingen.de/pb/plabase.php) was used to predict genes in Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 that are potentially involved in plant growth promotion41. Further, all the predicted gene functions were validated through BLASTp analysis (protein-protein comparison using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool).

Prediction of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes

Antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSMASH) v7.1.0 platform42, combined with its other provided features, including KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, MIBiG cluster comparison, ActiveSiteFinder, RREFinder, Cluster Pfam analysis, Pfam-based GO term annotation, TIGRFam analysis, TFBS analysis, and NCBI genomic context links, were used to predict the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGCs) present in the Bmkn7 genome associated with secondary metabolites43.

Furthermore, protein sequences were locally analyzed using InterProScan (version 4.7)44 to predict functional domains and provide additional annotation support for the biosynthetic gene clusters.

Additionally, to further understand, BAGEL4 - RiPPs miner45 and NaPDoS46, were used to mine BGCs for bacteriocin and determine the presence of keto synthase (KS) and condensation (C) domain, respectively.

Plant growth-promoting and antimicrobial properties of Bmkn7

In vitro plant growth-promoting (PGP) assays

Germination and effect of Bmkn7 on Pokkali seeds

The effect of Bmkn7 on rice seedlings was analyzed using VTL9 Pokkali rice seeds. Briefly, dehulled seeds were surface-sterilized using 7% sodium dichloroisocyanurate dihydrate, thoroughly rinsed with sterile distilled water, and allowed to sprout in double-sterilized distilled water for 24 h under dark conditions. The germinated seeds were then transferred to sterile CleriGel plates for continued growth. Five-day-old, uniformly germinated sterile seedlings were aseptically transferred to phytajars containing nitrogen-free half-strength Hoagland’s solution under hydroponic conditions. A 30 µL Bmkn7 suspension (OD600 = 0.3) was added to each phytajar, while phytajars without Bmkn7 served as controls. A total of 25 Pokkali seedlings were used for each treatment group (control and Bmkn7-inoculated), with each seedling considered a biological replicate (n = 25). After 11 days of growth, both Bmkn7-treated and control plants were uprooted, and various growth parameters, including germination, root length, and shoot length, were measured. Plant growth parameters were recorded individually, and mean ± standard deviation (SD) values were calculated. Comparative bar graphs were generated to illustrate differences between untreated control plants and Bmkn7-treated plants. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. Additionally, the recovery of Bmkn7 from seedling roots was performed by serial dilution of seedlings at 12 days post inoculation (dpi) using R2AN medium as the base medium.

Other phenotypic assays conducted to determine the plant growth-promoting traits of Bmkn7, involves:

-

(i)

Phosphate solubilization assay - The ability of Bmkn7 for phosphate solubilization was tested using the selective medium Pikovskaya’s (PVK) agar (Hi-Media - M520), used for the screening of microorganisms that can solubilize inorganic phosphate from tri-calcium phosphate47. The procedure includes inoculating 10 µL of the overnight-grown culture of Bmkn7 suspension (OD600 = 0.8) at the center of the prepared PVK agar plates and incubating at 30 °C for 2 days. The formation of a clear halo zone around the colony indicates inorganic and organic phosphate solubilization.

-

(ii)

Production of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase – ACC utilization ability was checked by growing Bmkn7 on a minimal salts medium (MM) (in gL− 1): K2HPO4, 0.8; KH2PO4, 0.2; MgSO4.7H2O, 0.2; CaCl2.2H2O, 0.2; NaCl, 5; NH4Cl, 1; that contained 5 g/L of glucose and 3mM ACC as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, respectively. ACC deaminase activity was quantified using cells grown for 24 h on MM agar plates supplemented with ACC. Briefly, bacterial cells were scraped from the agar surface, washed twice with 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), and resuspended in 200 µL of 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.5). 10 µL of toluene was added to 200 µL of the cell suspension to permeabilize the cells, followed by vortexing for 30 s. A reaction mixture was prepared by adding 5 µL of 0.5 M ACC to 50 µL of the toluenized cells and incubating at 30 °C for 30 min. A negative control was prepared using 50 µL of the toluenized cell suspension without ACC. ACC deaminase activity was determined by measuring the production of α-ketobutyrate, following the method described by48. Protein concentration in the cell extracts was estimated using the Bradford assay49.

Siderophore production

Siderophore production was performed using the Chrome Azurol S (CAS) assay50 with slight modification using Potato dextrose (PDA) as the basal medium. The procedure involves spotting 20 µL of Bmkn7 culture (OD600 = 0.9) at the center on CAS-added PDA medium and incubating at 30 °C for 3 to 7 days. A color change from blue to orange/yellow or a halo zone around the isolate indicates a positive for siderophore production. The extent of zone formation around the colony was determined as an indicator of the efficiency of siderophore production on the plate, and the siderophore production in broth was quantified using the microplate method51.

Effect of iron concentration on siderophore production

To evaluate the siderophore production under varying iron concentrations, Bmkn7 was grown under iron-starved conditions by adding the medium with 75 µM of 2,2’dipyridyl (an iron chelator) and under iron-abundant conditions with 100 µM of ferric chloride using the standard protocol as described in the above section.

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity of Bmkn7 against various phytopathogenic fungi and bacteria was determined using a dual culture plate assay52 and cross-streak method53, respectively.

Fungal strains used in the study included Macrophomina phaseolina, Alternaria alternata, Rhizoctonia solani obtained from Tstanes Biofertilizer Company Pvt. Ltd., Coimbatore, India, and Fusarium oxysporum (NFCCI 745) from the National Fungal Culture Collection of India (NFCCI), Pune, India. The inhibitory activity was assessed by determining the growth inhibition of pathogenic fungi. The method involves smearing a straight line (1.5 cm thickness) of 25 µl of Bmkn7 culture (106 CFU/mL) onto a PDA medium and incubating at 30 °C for 48 h. After 48 h of incubation, 1 cm² fungal mycelial discs were cut from actively growing fungal plates using a sterile cork borer and placed on opposite sides of the smeared plates (4 cm away from thesmeared Bmkn7 strain). The fungal plug (devoid of Bmkn7 smear) was used as a control. These plates were then incubated at room temperature until the control plate showed complete coverage of the fungal mycelia. The radial mycelial growth of the fungus was determined, and the mycelial inhibition was calculated by measuring the inhibition distance between the confronted microbes (distance of the fungal mycelium to the Bmkn7 strain).

Antibacterial studies were also performed using the same confrontation method. Briefly, the bacterial pathogens were streaked perpendicularly across the 2-day-grown Bmkn7 smeared on NA plates, followed by incubation for 4 days at 37 °C. The inhibition distance was calculated by measuring the distance between the confronted strains. Bacterial strains tested for this study include the Environmental strain of the taxa, Mycobacterium sp. P3A86, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus.

The same protocol was employed to assess the antimicrobial activity of Bmkn7 under the iron conditions outlined in the above section, with a slight modification wherein the CAS dye was excluded.

The antifungal activity of the cell-free crude extracts (˷0.1 g/mL) of Bmkn7 was also assessed against the fungus M. phaseolina using the diffusion method54.

Extraction and antagonistic effect of secondary metabolites

The cell-free culture filtrate of Bmkn7 was obtained from third-day post-inoculation broth grown in PDA by centrifugation. This filtrate was extracted using ethyl acetate in a 1:1 ratio for 2 h. The obtained organic and aqueous phases were separated using a separating funnel. The solvent phase, containing the metabolite, was subsequently concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator, and the obtained dry residue was resuspended in ethyl acetate (EtoAc).

Similarly, to extract the active compounds from the agar, the bacterial culture was smeared on one side (half part) of a PDA plate and incubated for 5 days at 30 °C. After incubation, the agar from the opposite side (devoid of bacterial cells) was sliced into small pieces (1 × 1 cm). The agar pieces were extracted in two conditions with ethyl acetate and methanol for 2 h. The obtained extracts were concentrated using the rotary vacuum evaporator and re-dissolved in ethyl acetate and distilled water, respectively.

The extracted samples were analyzed using advanced analytical techniques, including High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS), following the method described by55 with slight modifications. Briefly, all the extracted samples were re-dissolved in methanol and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter and injected into an LC-MS 8045 system (Shimadzu, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of 70% solvent A (methanol with 0.1% formic acid) and 30% solvent B (water with 0.1% formic acid), delivered at a 1 mL/min flow rate. Separation was carried out on a C18 column with ultraviolet (UV) detection using a diode array detector, followed by mass analysis via electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative scanning modes. For high-resolution analysis, a Thermo Scientific Exactive Orbitrap LC-MS system was used in ESI mode, and the HRMS data were reported as mass-to-charge ratios (m/z).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in biological triplicates (n = 3), and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 8. Depending on the type of experiment, different tests were applied: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD for siderophore production under varying iron conditions, Dunnett’s test for siderophore production, paired t-tests for antifungal inhibition assays, one-sample t-tests for antibacterial inhibition relative to baseline, and Pearson correlation for growth pattern analysis.

Results and discussion

Isolation and general genome features of Bmkn7

A potential strain, Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 was identified among twenty-five diverse siderophore-producing rhizobacteria shortlisted from a collection of 200 bacterial isolates obtained from rice varieties cultivated in the underexplored saline-affected coastal regions of Kerala, India. The partial 16 S rRNA gene sequencing analysis revealed that these isolates belonged to various taxonomic genera, including Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Pantoea, and Burkholderia (Supplementary Table S1). Based on its relatively higher siderophore production compared to other isolates, Bmkn7 was selected for further studies (Supplementary Fig. S1).

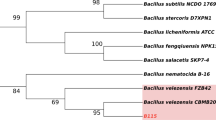

In order to gain insights into the genes related to plant growth-promoting traits and the biocontrol-related secondary metabolites, the whole genome sequencing of Bmkn7 was performed using a hybrid approach combining Illumina and Nanopore platforms. The analysis resulted in a complete genome of 8,397,732 bp with ~ 147× Illumina coverage and ~ 53× Nanopore coverage, which together provided sufficient depth for accurate hybrid assembly. Furthermore, the CheckM analysis (v1.2.3) of the genome assembled using MaSuRCA v. 3.3.7 exhibited 100% genome completeness without contamination, confirming its high-quality assembly. A detailed summary of the genome assembly metrics is provided in Supplementary Table S2. The assembled genome (Fig. 1), comprising three contigs, was scaffolded into a single circular sequence with a G + C content of 66.5%. The NCBI annotation of Bmkn7 (accession number JBGCUH000000000) revealed a total of 7,739 genes, including 7,646 protein-coding sequences (CDSs) and 93 RNA genes. NCBI results also identified Bmkn7 as belonging to the Burkholderia genus, showing 98.52% Average Nucleotide Identity (ANIm%) with B. reimsis BE51 (not validly published), a strain isolated from the maize rhizosphere. The phylogenetic analysis, performed with the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach, further confirmed the placement of Bmkn7 within the B. cepacia complex (Bcc) (Fig. 2), confirming closest to the B. reimsis BE51, which was recently claimed to be within the B. cepacia group56. The GenBank accession numbers of all strains used in this analysis are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Phylogenetic tree of Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 and reference strains of established Burkholderia species. The tree was generated using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) method implemented in the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) based on whole-genome sequences, illustrating the evolutionary relationships of Bmkn7 within the genus.

Genes, gene clusters, and antimicrobial compounds associated with biological control of Bmkn7

Burkholderia is well known for producing diverse secondary metabolites, including antimicrobial compounds with biocontrol potential57. Accordingly, the secondary metabolite biosynthetic potential of Bmkn7 was investigated using antiSMASH analysis. The analysis predicted 20 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) (Fig. 3), including those encoding non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), type I polyketide synthases(T1PKS), NRPS-like systems, terpenes, and other metabolite classes. Among these, three clusters, Region 1.2, Region 2.8, and Region 3.2, showed 100% similarity to known clusters responsible for the synthesis of pyrrolnitrin (MIBiG BGC0000924), pyochelin (MIBiG BGC0002678), and ornibactin (MIBiG BGC0002569), respectively. In addition, several clusters, such as Region 1.5 (bolagladin, 19%, MIBiG BGC0002327), Region 2.4 (dehydrofosmidomycin, 15%, MIBiG BGC0001859), and Region 2.5 (N-acyloxyacyl glutamine, 50%, MIBiG BGC0001684), shared partial similarity with known biosynthetic gene clusters. In contrast, others, including clusters related to terpenes, hydrogen cyanide, CDPS, RiPP-like, and T1PKS, showed no similarity to any known clusters, as illustrated in the antiSMASH gene cluster maps (Supplementary Fig. S2). These diverse arrays of BGCs underscore the biosynthetic versatility of Bmkn7 and suggest the ability of Bmkn7 to synthesize a wide range of complex bioactive compound clusters.

Based on the biosynthetic potential, Bmkn7 was further screened using the confrontation method to detect the antimicrobial activity, which revealed broad-spectrum antagonistic effects against several phytopathogenic fungi and bacterial strains (Supplementary Fig. S3). The dual plate assay results showed potential antifungal activity against M. phaseolina, F. oxysporum, and A. alternata, evidenced by substantial inhibition of fungal mycelial growth, with inhibition zones exceeding 15 mm (Supplementary Table S4), with the highest inhibition towards M. phaseolina. Similarly, the cross-streak method demonstrated notable antibacterial activity of Bmkn7 against E. coli, S. aureus, and Mycobacterium sp. P3A86.

Among the predicted biosynthetic gene clusters, the identified three clusters (regions: 1.2, 2.8, and 3.2) that showed 100% similarity to known biosynthetic clusters responsible for the production of Pyrrolnitrin, Pyochelin, and Ornibactin, respectively, have been further confirmed via BLASTp analysis (Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Table S6). Pyrrolnitrin (Cluster 2: 302,952 − 344,037) is a well-established antibiotic and biocontrol compound58,59. Similarly, Pyochelin (Cluster 13: 3,083,339–3,137,229) and Ornibactin (Cluster 17: 2,003,183–2,068,257) are well-known siderophores involved in iron scavenging in Burkholderia strains. Previous studies have also identified these siderophores as effective biocontrol compounds28. As siderophores are known to be associated with antimicrobial activity, we conducted in vitro assays under laboratory conditions to investigate their potential role in the antimicrobial effects of Bmkn7.

Siderophore-dependent antimicrobial activity of Bmkn7

The siderophilic bacteria60 act as biocontrol agents by suppressing phytopathogens through competitive iron sequestration11,61,62. Under low-iron conditions, microorganisms that produce siderophores form ferric-siderophore complexes, making iron unavailable to other organisms. However, the producing strain can access this complex through a specific outer membrane receptor, thus potentially limiting pathogen growth63. To investigate the role of siderophore in the antimicrobial activity of Bmkn7, we initially examined the siderophore production under three defined conditions: iron-abundant (medium with iron, [Fe³⁺]), iron-starved (medium with an iron chelator), and control (medium alone) using the CAS agar plate assay. Here, 100 µM iron and 75 µM 2,2’ dipyridyl were chosen as the appropriate concentrations that did not affect the microbial growth (Supplementary Fig. S4) to establish iron-abundant and iron-starved conditions, respectively.

Siderophore release was most pronounced under iron-starved conditions (14–15 mm), followed by the control (5–6 mm). In contrast, no siderophore production was detected under iron-abundant conditions (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. S5), confirming the suppression of siderophore synthesis of Bmkn7 in the presence of iron. The above findings align with earlier studies showing that siderophore production decreases progressively with increasing exogenous iron levels, indicating iron-dependent regulation of siderophore synthesis64.

Effect of iron availability on siderophore production and fungal inhibition by Bmkn7. A: The CAS agar plate assay shows siderophore production by Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7: (a) control plate (medium alone); (b) iron-starved condition, and (c) iron-abundant condition. Siderophore production was higher in (b) compared to (a) [(b)> (a)], while no siderophore production was observed in (c). B: Inhibition of fungal growth by Bmkn7 on PDA plates under varying iron conditions. (a) Control and iron-abundant plates showed a similar inhibitory effect against Macrophomina phaseolina. (b) Graphical representation of fungal growth in control and iron-abundant conditions, without and with Bmkn7. No significant difference was observed between the treatments (p > 0.05).

Further, we analyzed the inhibitory activity under iron-abundant conditions to determine whether the antimicrobial activity was solely attributable to the siderophore production. The result (Supplementary Fig. S6) revealed that the antibacterial activity against E. coli was abolished entirely, indicating a siderophore-dependent mechanism; however, partial inhibition of Mycobacterium sp. P3A86 and S. aureus persisted, suggesting a possible synergistic effect between siderophores and other antimicrobial compounds contributing to the antagonistic activity of Bmkn7.

Further, LC-MS analysis of the crude extract of Bmkn7 obtained via ethyl acetate extraction under these three conditions supported the observation that siderophore production is suppressed in the presence of iron. Specifically, no mass corresponding to pyochelin was detected under iron-abundant conditions, where pyochelin has a theoretical mass of 324 Da, and its ionized form appears at m/z 325 [M + H] + in positive mode and m/z 323 [M − H]⁻ in negative mode, eluting at a retention time of 19–22 min. In contrast, pyochelin was present under normal control conditions, and a notably increased relative abundance was detected under iron-starved conditions. Despite these differences in siderophore production, antifungal activity of the extracts against Macrophomina phaseolina remained comparable across all conditions (Fig. 5A).

Antifungal activity and chromatographic/mass spectrometric analysis of Bmkn7 extracts. (A) Agar-plate bioassays showing inhibition of Macrophomina phaseolina by three extracts: (a) ½PDA (control), (b) ½PDA + Fe chelator (iron-starved), and (c) ½PDA + Fe (iron-abundant), each accompanied by the corresponding HPLC chromatogram (PDA detection at 254 nm; retention time: 0–30 min). LC–MS spectra of the extracts are shown below: (I) positive ionization mode and (II) negative ionization mode. The peak corresponding to pyochelin (theoretical mass324 Da; detected at m/z 325 [M + H] + in positive mode and m/z 323 [M–H]– in negative mode) is indicated by a red arrow. (B) HPLC–UV chromatograms of Bmkn7 culture filtrates extracted from (a) agar and (b) broth.

Siderophore-independent antimicrobial activity of Bmkn7

Bmkn7 retained its antifungal activity against M. phaseolina even under iron-abundant conditions (Figs. 4B and 5A), suggesting a siderophore-independent mechanism. This observation aligns with previous studies where several isolates are known to produce antagonistic secondary metabolites alongside siderophores65,66.

Metabolite extraction was performed to identify the compound responsible for the antagonistic activity against M. phaseolina. Moreover, considering the rising demand for large-scale microbial production of antifungal metabolites as a safer alternative to chemical pesticides and fungicides67, evaluating the extraction efficiency of such bioactive compounds from Bmkn7 was essential. Accordingly, organic solvent extraction was carried out on the cell-free culture filtrate of Bmkn7. Agar well diffusion assays with crude extracts of Bmkn7 from broth and agar demonstrated a significant difference in the inhibitory effects on the growth of M. phaseolina. While the ethyl acetate extract from the cell-free broth produced a 10 mm inhibition zone, no inhibition was observed with the agar extract. However, methanol extraction from the agar completely inhibited fungal growth (Fig. 6). Notably, this variation in fungal growth suppression, observed under these conditions, along with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis, suggests the presence of distinct antimicrobial compounds in each extract (Fig. 5B). Additionally, while analyzing the antifungal compound, cross-referencing the obtained masses from LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry-Triple quadrupole) and HRMS (High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry) with reported secondary metabolites in the literature revealed no matching masses corresponding to known antimicrobial metabolites, indicating the presence of a unique bioactive compound.

Antifungal activity of culture filtrates of Bmkn7 against Macrophomina phaseolina using the sterile filter disc diffusion method. (a) Control (methanol), (b) Ethyl acetate extract of culture filtrate obtained from broth culture, (c) Ethyl acetate extract of culture filtrate obtained from agar plate culture, (d) Methanol extract of culture filtrate obtained from agar plate culture.

Other gene clusters encoding secondary metabolites in Bmkn7

Though the genome of Bmkn7 possesses the pyrrolnitrin biosynthetic gene cluster, pyrrolnitrin was not detected in culture filtrates based on its mass through HRMS and LC-MS/MS analysis. Additionally, Bmkn7 did not exhibit any antagonistic effect against Rhizoctonia solani (Supplementary Fig. S3), a pathogenic microbe known to be inhibited by pyrrolnitrin based on earlier studies68,69. This discrepancy between the presence of the gene and its compound detection suggests that factors such as regulatory mechanisms or the provided environmental conditions may limit pyrrolnitrin production or activity in this strain. Consequently, further genomic analysis was conducted to investigate the novel compound responsible for the antifungal activity against M. phaseolina.

In addition to the known clusters, antiSMASH analysis predicted twelve orphan biosynthetic gene clusters in the Bmkn7 genome, including a CDPS, a RiPP-like, and a T1PKS cluster. While these clusters could be categorized based on their biosynthetic domain types, they showed no similarity to characterized gene clusters in the reference database, suggesting that they may encode novel or understudied bioactive metabolites (Fig. 3).

The three orphan clusters- CDPS, RiPP-like, and T1PKS- clusters, spanning the 472,127–492,837 bp region of contig-3, the 918,600–929,415 bp region of contig-3, and the 969,980–1,017,614 bp region of contig-2, corresponding to Cluster 3, Cluster 4, and Cluster 16, respectively, were selected for further investigation. Although the exact function of these clusters in Bmkn7 remains to be elucidated, previous studies have reported significant bioactivities for compounds derived from CDPS clusters, including antifungal properties70,71,72. Similarly, there were studies on T1PKS clusters that could encode diverse functions, including putative antifungal compounds73,74. These findings lead us to hypothesize that the uncharacterized clusters may contribute to the antifungal activity observed in Bmkn7.

Further analysis of these three clusters was carried out based on the presence of key protein domains using Pfam (Supplementary Fig. S7) and functional interpretation via InterProScan, which suggested their potential to encode bioactive secondary metabolites. Cluster 3 may encode a siderophore-like compound, as this cluster mainly features TonB, ExbD, SBP_bac_3, and 2OG-Fe (II)_Oxy_3 domains, which are typically associated with iron acquisition, along with an MFS_1 transporter, indicating a potential role in iron chelation. Cluster 4 contains domains such as Linocin_M18 and HTH_1, which may indicate antimicrobial potential, and a Dyp_perox domain, possibly related to oxidative metabolism. Cluster 16 is predicted to encode a complex secondary metabolite, as it contains domains such as Ketoacyl-synt, Ketoacyl-synt_C, KAsynt_C_assoc, Acyl_transf_1, PS-DH, Methyltransf_23, and the HTH_18 transcription factor, all of which suggest the production of a polyketide-derived compound. Furthermore, the presence of Capsule_synth, Glycos_transf, and fatty acid desaturase domains hints at the incorporation of sugar and lipid moieties, underscoring the chemical complexity of the metabolite encoded.

Although Pfam-based prediction provides broad insight into genomic region prediction75, additional validation was performed using BAGEL4, a tool specialized in detecting RiPP bacteriocin, and NaPDoS, a phylogeny-based tool that classifies ketosynthase (KS) and condensation (C) domains from PKS and NRPS pathways and links them to known biosynthetic lineages. The BAGEL4 analysis was consistent with Pfam observations, identifying one cluster associated with a putative bacteriocin (Linocin_M18) (Supplementary Fig. S8A), suggesting its potential antimicrobial activity. Notably, this region was not identified as similar to known clusters in antiSMASH, likely due to variations in biosynthetic organization.

Likewise, NaPDoS analysis identified four KS domains in Bmkn7 (Supplementary Fig. S8B), including WP_369466096.1_5_430, which aligns with cis-AT polyketide synthases related to pellasoren biosynthesis, located within Region 3.1. Although pellasoren is known for its cytotoxic activity76, a previous study reported a biosynthetic gene cluster with 33% similarity that was predicted to encode an antifungal metabolite with a hybrid NRPS-PKS structure77. Thus, it further suggests that structural modifications in the gene cluster encoding pellasoren may give rise to a bioactive compound with altered or novel functional properties. Moreover, the T1PKS domain identified in Cluster 16 (Supplementary Fig. S8C) reinforces the potential of this region to produce a polyketide-related secondary metabolite. Additionally, InterProScan analysis classified the biosynthetic gene in Cluster 16 as a member of the “Polyketide and Non-ribosomal Peptide Biosynthesis Enzymes” protein family (IPR050091), further implicating its role in complex secondary metabolite production.

Thus,integrating all these findings, we hypothesize that all identified orphan gene clusters may contribute to the differential antimicrobial activity observed in Bmkn7, positioning this strain as a promising candidate for novel compound discovery. However, experimental validation and compound isolation are necessary to establish definitive links between these genomic predictions and the antifungal activity against M. phaseolina.

Genes and gene clusters associated with plant growth promotion

To investigate the genomic composition of Bmkn7 and to determine its plant-associated potential and environmental adaptability, we examined the SEED subsystem features accessible through the RAST server. The analysis indicated that many protein-coding genes were classified under the amino acids and derivatives category (568), followed by those associated with carbohydrates (384), suggesting a strong metabolic capacity for utilizing diverse nutrient sources. Additionally, many genes were involved in protein metabolism (233) and respiration (158), which may indicate an active energy metabolism supporting cellular functions. Conversely, the comparatively lower number of genes associated with protein metabolism than carbohydrates suggests that the Bmkn7 strain may be more adapted to utilizing plant-derived carbohydrate substrates78. Furthermore, the metabolism of aromatic compounds (132) suggests a potential role in the degradation of complex organic molecules. In contrast, iron acquisition and metabolism (84) may be crucial for survival in iron-limited environments. Moreover, the presence of membrane transport genes (128) highlights the ability of Bmkn7 to interact with its surroundings, possibly aiding in nutrient uptake and environmental stress adaptation. Notably, 112 genes were annotated under the stress response category, further supporting the adaptability of Bmkn7 to challenging environments (Fig. 7). These features, including genes for nutrient utilization, membrane transport, stress responses, and iron acquisition, suggest that Bmkn7 harbors multiple genomic traits that may contribute to its role as a plant growth-promoting bacterium.

Plant growth-promoting traits

We observed multiple plant growth-promoting traits in Bmkn7, as represented in Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Table S8.

The genome analysis of Bmkn7 revealed genes associated with phosphate solubilization, including the entire cluster of PQQ-dependent glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) complex (pqqA-E)79, along with GntR family transcriptional regulator and a GntP family permease, which play a significant role in regulating and transporting gluconate, contributing to the solubilization of inorganic phosphate. It also possessed the citrate synthase gene, gltA, along with the CitMHS family transporter genes, which have distinct significance in microbial phosphate solubilization80. This genome analysis was further confirmed by a phenotypic assay performed using Pikovskaya’s (PVK) agar medium (Fig. 8A). Additionally, Bmkn7 also possesses pyrophosphate kinase 1 (ppk1) and exopolyphosphatase (ppx) genes, which play a significant role in phosphate homeostasis, and also the genes associated with the ABC transporter complex (pstS, pstC, pstA, pstB) and the Pho regulon (phoU, phoB, phoR, phoH) for phosphate signaling81. Along with the genes for phosphate transport, it also possesses genes for sn-glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) transport, phosphonate metabolism (phnY, phnA, phnV, phnT, phnS), and organic phosphate solubilization genes, such as alkaline phosphatases, which are crucial for accessing phosphate from soil in various forms.

In addition to phosphate solubilization, Bmkn7 exhibits other plant growth-promoting mechanisms, such as ACC deaminase production, crucial for stress adaptation by lowering plant ethylene levels and boosting plant growth under challenging conditions, such as salinity stress82. Bmkn7 possesses the gene encoding 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (WP_059587145.1), required for ACC deaminase activity. Additionally, functional analysis confirmed that, when cultured in defined mineral salts media, Bmkn7 can utilize ACC as the sole nitrogen source (Fig. 8B) and could exhibit an ACC deaminase activity of 3.1415 ± 0.04 µmol of α-ketobutyrate per hour per milligram of protein. Notably, the Bmkn7 genome also contains genes related to chemotactic responses and polyamine production, such as spermidine (WP_369464441.1, WP_042973815.1, WP_021158551.1), which regulates ethylene production and contribute to cellular growth, development, and stress responses83,84.

Phytohormone production

Besides its role in nutrient metabolism, the Bmkn7 genome encodes several plant growth-promoting genes, including those responsible for indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production and salicylic acid (SA) production.

Although Bmkn7 does not encode the key enzymes typically involved in IAA biosynthesis, it contains genes associated with tryptophan biosynthesis, a precursor to IAA. Additionally, genes like iaaH encoding indoleacetamide hydrolase (WP_369464462.1), indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (WP_369465928.1; WP_369466839.1), and nitrilase-related carbon-nitrogen hydrolase (WP_369466402.1) assist in the conversion of intermediate compounds in the IAA biosynthetic pathway, contributing indirectly to IAA production85.

Similarly, salicylic acid (SA) production genes, including isochorismate synthase (WP_369465665.1) and isochorismate lyase (WP_021163799.1), were identified, crucial for plant-microbe interactions and defense mechanisms86.

Additionally, Bmkn7 can produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as isoprene and 2,3-butanediol, which not only promote plant growth and stress mitigation but also modulate plant physiological responses and enhance plant resistance to stress factors87.

Plant-colonization traits in Bmkn7

Rhizosphere bacteria exhibit several traits required to establish their association with plants, which are necessary for survival and colonization88.

The genome of Bmkn7 possesses diguanylate cyclase (DGC) proteins and phosphodiesterase (PDE) proteins characterized by the presence of a GGDEF domain (WP_021163392.1) and an EAL domain (WP_027790583.1), respectively. These play an essential role in controlling the second messenger c-di-GMP (bis-(3’−5’)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate), one of the predominant factors to be a proficient plant colonizer, as it governs the bacterial lifestyles to switch between the sessile (biofilm-forming) and motile states89.

Since motility is a major factor in bacterial colonization, and Burkholderia strains are known for this trait, we analyzed the associated genes90. In addition to the presence of all flagellar coding genes (flgA-N, flhA-D, F, fliD-T, fleN, mot A, B), Bmkn7 also harbors chemotaxis (cheA-D, R, W-Z) and 21 methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) genes, including PAS domain-containing MCP (Supplementary Table S9), enabling the bacterium to sense and respond to environmental and chemical cues91.

Furthermore, the genome harbors almost all genes for Type IV pili and fimbriae (Supplementary Table S10), essential for effective root colonization92. The presence of curli-related genes (Supplementary Table S11), which facilitate cell-cell adhesion via interactions with proteins like fibronectin, further supports the role of Bmkn7 in plant colonization. Additionally, the BCS gene cluster (Supplementary Table S12) for cellulose production indicates that Bmkn7 can form biofilms, which are crucial for stable attachment and persistent colonization of plant surfaces93. Bacterial cellulose further contributes to biofilm integrity by promoting flocculation, supporting aerobic microenvironments, and strengthening attachment to plant surfaces94, underscoring the potential of Bmkn7 to establish robust plant-associated biofilms and enhance colonization. The genome also contains cellulase genes (WP_369465308.1) belonging to the glycosyl hydrolase family, which may facilitate plant cell wall degradation and host colonization95, and a chitinase gene (WP_060230667.1), which may degrade fungal cell walls, contributing to biocontrol activity96. Altogether, all these features underline the strong colonization capability and adaptability of Bmkn7 towards plant-associated environments.

Iron acquisition

In addition to the above-identified biosynthetic gene clusters for siderophores such as pyochelin and ornibactin, genome analysis also revealed the presence of several complementary genes encoding specialized iron transport and storage systems, which facilitate efficient uptake, utilization, and regulation of iron under variable environmental conditions. Bmkn7 harbors specialized transport systems, such as ferrochelatase (hemH), and hemin uptake proteins (hemP), siderophore-interacting proteins, TonB-dependent siderophore receptor proteins, ferric hydroxamate ABC transport permease (fhuB), and siderophore-iron reductase (fhuF) for capturing and importing external iron. The genome also encodes iron storage proteins, including bacterioferritin (bfr) and five copies of ferritin-like domain-containing proteins (Supplementary Table S13). All these genes collectively facilitate efficient iron acquisition by ensuring sufficient iron uptake under iron-limited conditions, as typically found in saline soils, while enabling the bacterium to regulate internal iron to prevent toxicity from excess iron, thereby supporting plant growth. These genes also play a significant role in chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis, where iron is critical97. Additionally, Bmkn7 can colonize various ecological niches due to these diverse iron uptake systems, further supporting its significant environmental and physiological roles98.

Other plant-associated traits

The Bmkn7 genome also encodes several other genes related to plant interactions, supporting its metabolic versatility. These include genes involved in nitrogen assimilation, including nitrate/nitrite transport, denitrification, and nitrite reductase (nirB, nirD), supporting its role in nitrogen cycling and the degradation of nitroaromatic pollutants. It also encodes genes for urea metabolism (urease operon, urtEDCBA). The genes encoding sulfur assimilation (cysT, cysW, cysD, cysN, cysC), along with sulfonate metabolism (TauD dioxygenases, sulfatases), allow it to thrive in sulfur-rich environments and efficiently metabolize diverse sulfur compounds99.

Additionally, Bmkn7 harbors genes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidases, thioredoxin (trxA, trxB), OsmC family protein, hydroperoxide reductase, and glutaredoxin, which encode oxidative stress resistance mechanisms that help to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), essential for plant-microbe interactions and promoting plant growth100,101. The Kdp system genes (kdpA, kdpB, kdpC, kdpE, kdpF), which aid in potassium uptake, particularly under saline conditions, help in osmotic homeostasis102. Bmkn7 also possesses proline, glycine betaine, and trehalose genes to regulate osmotic stress.

Furthermore, Bmkn7 is also capable of anaerobic respiration, utilizing fumarate and formate as electron acceptors, providing a metabolic advantage in oxygen-limited environments. It also contains genes for the degradation of aromatic compounds (3-oxoadipate, anthranilate, and phenylacetate pathways), enabling it to metabolize plant-derived aromatic compounds and contribute to pollutant bioremediation in the rhizosphere.

All these traits, detailed in Supplementary Tables S14–S19, emphasize the ecological adaptability of Bmkn7 as a plant-associated rhizobacterium.

Comparative genomic analysis of Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 and plant-associated beneficial strains within the Bcc Genomovar I

A comparative analysis was conducted to assess the relatedness of Bmkn7 to plant-associated beneficial strains of Burkholderia within the Bcc genomovar I. For this, plant/animal pathogenic strains such as B. cepacia ATCC 25416 and B. cepacia ATCC 25416 UCB 717 (represented as B. cepacia UCB 717) and representative plant-associated strains: B. reimsis BE51, B. cepacia BRDJ, and Burkholderia sp. AU4i were selected. The details of the genomes compared here are shown in Supplementary Table S20. The analysis revealed that measures of similarity based on the AAI value, ANI value, and dDDH analyses between Bmkn7 and the other compared strains exceeded the threshold of species delineation (> 95% ANI and AAI, and > 70% dDDH)103, confirming the placement of Bmkn7 within the Bcc genomovar 1 (Table 1). However, none of the comparisons exceeded the 99.5% ANI threshold, indicating that Bmkn7 belongs to the same species as the selected reference strains, but likely represents a distinct subspecies or lineage104. This divergence may reflect underlying functional or ecological differentiation, as Bmkn7 was isolated from a salinity-prone rice field.

Further, a deeper comparative analysis was performed using OrthoVenn3 to identify conserved and unique protein-coding sequences. The study identified 7,205 orthologous clusters across all strains, of which 6,168 were shared. Notably, Bmkn7 possessed 272 unique clusters (singletons), highlighting its distinct genomic features. Additionally, Bmkn7 shared most clusters with B. reimsis BE51 and Burkholderia sp. AU4i while sharing the fewest with B. cepacia ATCC 25416 and B. cepacia UCB 717 (9a). Furthermore, when comparing Bmkn7 with plant-associated and pathogenic strains, it was found that Bmkn7 shared a more significant number of homology-predicted proteins with B. reimsis BE51 (72), Burkholderia sp. AU4i (133), and B. cepacia BRDJ (44). In contrast, it displayed no specific homology-predicted proteins with the pathogenic strains B. cepacia ATCC 25416 (0) and B. cepacia UCB 717 (0) (9b). Moreover, the maximum likelihood tree constructed based on homologous proteins grouped into orthogroups suggested that Bmkn7 is indeed related to the plant-associated strains, as Bmkn7, Burkholderia sp. AU4i and B. reimsis BE51 clustered together (9c). All these outcomes indicate that Bmkn7 is closely associated with plant-associated strains of B. cepacia.(Fig. 9 a-c)

Comparative genomic analysis of Burkholderia sp. Bmkn7 with selected Burkholderia cepacia strains. (a) Comparative analysis of orthologous gene clusters; (b) Venn diagram of the B. cepacia strains showing the number of Bmkn7 protein-coding sequences with that of (i) plant-associated B. cepacia strains and (ii) pathogenic B. cepacia strains; and (c) Phylogenetic relationship of Bmkn7 and selected B. cepacia strains based on marker proteins using maximum likelihood, highlighting the functional and evolutionary relationships of Bmkn7 in comparison with the selected strains.

Since Bmkn7 clustered with plant-associated Burkholderia strains, we further analyzed its genome for traits supporting this lifestyle using PLaBAse, a platform specialized in identifying genes linked to plant–bacterium interactions. The analysis confirmed the presence of genes linked to colonization (25%), competitiveness for adhesion and nutrients (21%), stress tolerance and biocontrol (18%), biofertilization (16%), bioremediation (9%), and stimulation of plant immunity (1%), thereby reinforcing its beneficial and plant-associated lifestyle of Bmkn7. Additionally, the Bmkn7 strain harbored genes encoding enzymes such as nitrile hydratase (WP_048023132.1, WP_059853627.1), phenylacetaldoxime dehydratase (WP_059853629.1), and feruloyl-esterase (WP_059495232.1), which enable catabolism of plant-derived compounds105, suggesting plant-associated adaptation of Bmkn7.

Since Burkholderia strains are known for their metabolic flexibility, the potential pathogenicity of Bmkn7 was further examined. Genome analysis revealed the absence of virulence genes encoding phytotoxins, such as toxoflavin, tropolone, and rhizoxin, suggesting a non-pathogenic interaction with plants. Notably, polygalacturonase, an extracellular enzyme involved in the degradation of pectin and typically present in pathogenic Bcc strains that cause soft rot, was absent in Bmkn7. The complete type III secretion system (T3SS) was also not detected, providing further evidence that Bmkn7 lacks key plant-pathogenicity mechanisms. Accordingly, the effect of Bmkn7 on rice seedlings was assessed to investigate its plant interaction further. The results indicated that Bmkn7 exhibited a non-pathogenic profile, as evidenced by the neutral effect on seed germination, root length, and shoot length (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Previous studies indicate that some environmentally adapted Burkholderia strains, which include opportunistic pathogens, may retain certain virulence-associated genes that help them survive in diverse ecological niches. However, these strains typically possess fewer key pathogenicity determinants compared to those infecting cystic fibrosis (CF) patients106. In contrast, Bmkn7 lacks several critical genomic features known to be associated with pathogenicity in clinical Burkholderia isolates. These features include the type III secretion system (T3SS) and the Burkholderia cepacia epidemic strain marker (BCESM), both of which are strongly linked to transmissibility and increased disease severity during CF outbreaks. Additionally, Bmkn7 does not have the vgrG-5 gene107 or the cable pili-associated 22-kDa adhesion gene105, both of which play a role in host colonization and airway infection.

The absence of these major pathogenicity determinants suggests that Bmkn7 does not carry the genomic traits typically associated with infections in humans or animals and is more aligned with a plant-associated environmental lifestyle. This interpretation is further supported by our preliminary plant interaction assays, which showed no harmful effects on the plant host. Coupled with its plant growth-promoting traits and demonstrated antimicrobial activity against plant pathogens, these characteristics highlight the potential of Bmkn7 as a promising biocontrol agent while also emphasizing the need for comprehensive biosafety assessments before its agricultural application.

Further, to explore the adaptive traits of Bmkn7, IslandViewer 4 was used to determine the Genomic Islands (GIs), the DNA regions acquired through horizontal gene transfer108. Results of GI prediction indicate that Bmkn7 possesses the highest number of GIs in Contig 1, followed by Contig 2 and Contig 3. The whole genome analysis of Bmkn7 revealed that approximately 30% of the genes within GIs encode hypothetical proteins, meaning their function is unknown109. From the GI prediction of each contig, it is clear that Contig 3 and Contig 2 contain a higher proportion of GI clusters encoding hypothetical proteins (35.3% and 34.7%, respectively), compared to Contig 1 (28%), suggesting that Contig 2 and Contig 3 could be rich reservoirs of these uncharacterized genes. In contrast, the entire Bmkn7 genome encodes only around 3% transposases, strongly suggesting more excellent genome stability of the strain, reflecting its adaptation110 (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Conclusion

The complete genome sequence analysis and phenotypic studies provided insight into the antimicrobial activities and plant growth-promoting properties of Burkholderia strain Bmkn7. Phylogenetic and genome comparisons confirmed Bmkn7 as one of the members of the plant-associated strains of B. cepacia. Detailedgenome characterization revealed the multifaceted beneficial properties of Bmkn7 with an array of genetic traits adapted to the plant-associated lifestyle, including siderophore production, phosphate solubilization, and ACC deaminase production, underscoring its potential for enhancing plant growth. Its oxidation resistance, biofilm formation, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) production, and stress tolerance traits also contribute to its ecological adaptability. More importantly, Bmkn7 exhibits a wide range of antagonistic activity against phytopathogens through siderophore production and the release of antimicrobial compounds. Additional experimental analysis revealed that the antimicrobial activity extends beyond the known compounds, suggesting the involvement of unidentified molecules. Further, genomic analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding diverse secondary metabolites confirmed the presence of 3 orphan clusters that may encode novel bioactive compounds. Data presented in this study position Bmkn7 as a valuable resource for discovering new antimicrobial substances. Future research will focus on identifying and characterizing these orphan BGC-derived compounds and evaluating the efficacy of Bmkn7 in planta for sustainable agriculture. Though Burkholderia strains are known for biocontrol and plant growth promotion, these findings are significant as they highlight the importance of exploring less-studied areas that may harbor such organisms capable of producing novel bioactive compounds with plant growth-promoting potential. This work contributes to the search for effective and environmentally friendly alternatives to chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

Altogether, this study identifies Bmkn7 as a potential addition to the plant-associated beneficial strains within environmental B. cepacia genomovar I, thus contributing to the expanding knowledge of this group.

Data availability

The whole genome sequence of Bmkn7 was deposited in NCBI with accession number JBGCUH000000000.

References

Bukhat, S. et al. Communication of plants with microbial world: exploring the regulatory networks for PGPR mediated defense signaling. Microbiol. Res. 238, 126486 (2020).

Mahmud, K., Makaju, S., Ibrahim, R. & Missaoui, A. Current progress in nitrogen fixing plants and Microbiome research. Plants 9, 97 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Screening of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and their abilities of phosphorus solubilization and wheat growth promotion. BMC Microbiol. 22, 296 (2022).

Timofeeva, A., Galyamova, M. & Sedykh, S. Prospects for using phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms as natural fertilizers in agriculture. Plants 11, 2119 (2022).

Ma, Y., Oliveira, R. S., Freitas, H. & Zhang, C. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of plant-microbe-metal interactions: relevance for phytoremediation. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 918 (2016).

Zahir, Z. A., Shah, M. K., Naveed, M. & Akhter, M. J. Substrate-dependent auxin production by Rhizobium phaseoli improves the growth and yield of Vigna radiata L. under salt stress conditions. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 1288–1294 (2010).

Singh, R. P., Shelke, G. M., Kumar, A. & Jha, P. N. Corrigendum: Biochemistry and genetics of ACC deaminase: a weapon to stress ethylene produced in plants. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1255 (2015).

Mansour, E. et al. Enhancement of drought tolerance in diverse Vicia Faba cultivars by inoculation with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria under newly reclaimed soil conditions. Sci. Rep. 11, 24142 (2021).

Ho, Y. N. et al. Specific inactivation of an antifungal bacterial siderophore by a fungal plant pathogen. ISME J. 15, 1858–1861. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00871-0 (2021).

Hosseini, A., Hosseini, M. & Schausberger, P. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance defense of strawberry plants against spider mites. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 783578 (2022).

Ghazy, N. & El-Nahrawy, S. Siderophore production by Bacillus subtilis MF497446 and Pseudomonas Koreensis MG209738 and their efficacy in controlling Cephalosporium Maydis in maize plant. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 1195–1209 (2021).

Timofeeva, A. M., Galyamova, M. R. & Sedykh, S. E. Bacterial siderophores: Classification, biosynthesis, perspectives of use in agriculture. Plants 11, 3065 (2022).

Karuppiah, V. et al. Development of siderophore-based rhizobacterial consortium for the mitigation of biotic and abiotic environmental stresses in tomatoes: an in vitro and in planta approach. J. Appl. Microbiol. 133, 3276–3287 (2022).

Lahlali, R. et al. Biological control of plant pathogens: A global perspective. Microorganisms 10, 596 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Insights into the biocontrol function of a Burkholderia gladioli strain against Botrytis cinerea. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0480522 (2023).

Antagonism, C. M. PATHOGEN SELF-DEFENSE: mechanisms to. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41, 501–538 (2003).

Buysens, S., Heungens, K., Poppe, J. & Hofte, M. Involvement of Pyochelin and pyoverdin in suppression of Pythium-induced damping-off of tomato by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 865–871 (1996).

Scavino, A. F. & Pedraza, R. O. The role of siderophores in plant growth-promoting bacteria. Bact Agrobiol Crop Product. Springer; pp. 265–285. (2013).

Louden, B. C., Haarmann, D. & Lynne, A. M. Use of blue agar CAS assay for siderophore detection. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 12, 51–53 (2011).

Sharma, P. & Thakur, D. Antimicrobial biosynthetic potential and diversity of culturable soil actinobacteria from forest ecosystems of Northeast India. Sci. Rep. 10, 4104 (2020).

Wahab, A. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria biochemical pathways and their environmental impact: a review of sustainable farming practices. Plant. Growth Regul. 104, 637–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-024-01218-x (2024).

Depoorter, E. et al. Burkholderia: an update on taxonomy and biotechnological potential as antibiotic producers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 5215–5229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7520-x (2016).

Compant, S., Nowak, J., Coenye, T., Clement, C. & Ait Barka, E. Diversity and occurrence of Burkholderia spp. in the natural environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 607–626 (2008).

Caballero-Mellado, J., Onofre-Lemus, J., Estrada-de Los Santos, P. & Martínez-Aguilar, L. The tomato rhizosphere, an environment rich in nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species with capabilities of interest for agriculture and bioremediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5308–5319 (2007).

Pal, G. et al. Endophytic Burkholderia: multifunctional roles in plant growth promotion and stress tolerance. Microbiol. Res. 265, 127201 (2022).

Mahenthiralingam, E., Baldwin, A. & Dowson, C. G. Burkholderia Cepacia complex bacteria: opportunistic pathogens with important natural biology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104, 1539–1551 (2008).

Vial, L., Chapalain, A., Groleau, M. & Déziel, E. The various lifestyles of the Burkholderia Cepacia complex species: a tribute to adaptation. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1–12 (2011).

Foxfire, A., Buhrow, A. R., Orugunty, R. S. & Smith, L. Drug discovery through the isolation of natural products from Burkholderia. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 16, 807–822.https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2021.1877655 (2021).

Krishnan, R., Lang, E., Midha, S., Patil, P. B. & Rameshkumar, N. Isolation and characterization of a novel 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase producing plant growth promoting marine Gammaproteobacteria from crops grown in brackish environments. Proposal for Pokkaliibacter plantistimulans gen. nov., sp. n. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 41, 570–580 (2018).

Zimin, A. V. et al. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics 29, 2669–2677 (2013).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 9, 75 (2008).

Grant, J. R. et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51,, W484–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad326 (2023).

Tatusova, T. et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624 (2016).

Bertelli, C. et al. IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic Islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W30–35 (2017).

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P. & Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2182 (2019).

Richter, M., Rosselló-Móra, R., Oliver Glöckner, F. & Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 32, 929–931 (2016).

Rodriguez-R, L. M. & Konstantinidis, K. T. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ Preprints ; (2016).

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Auch, A. F., Klenk, H. P. & Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 14, 1–14 (2013).

Sun, J. et al. OrthoVenn3: an integrated platform for exploring and visualizing orthologous data across genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W397–403 (2023).

Patz, S. et al. PLaBAse: A comprehensive web resource for analyzing the plant growth-promoting potential of plant-associated bacteria. BioRxiv ;2012–2021. (2021).

Medema, M. H. et al. AntiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W339–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr466 (2011).

Alam, K. et al. Isolation, complete genome sequencing and in Silico genome mining of Burkholderia for secondary metabolites. BMC Microbiol. 22, 323 (2022).

Blum, M. et al. InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025 mode longmeta? Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D444–D456 (2025).

van Heel, A. J. et al. BAGEL4: a user-friendly web server to thoroughly mine RiPPs and bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W278–W281 (2018).

Ziemert, N. et al. The natural product domain seeker napdos: a phylogeny based bioinformatic tool to classify secondary metabolite gene diversity. PLoS One. 7, e34064 (2012).

Sundararao, W. V. B. Phosphate dissolving organisms in the soil and rhizosphere. Ind. Jour Agr Sci. 33, 272–278 (1963).

Penrose, D. M. & Glick, B. R. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth‐promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol. Plant. 118, 10–15 (2003).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Schwyn, B. & Neilands, J. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160, 47–56 (1987).

Arora, N. K. & Verma, M. Modified microplate method for rapid and efficient Estimation of siderophore produced by bacteria. 3 Biotech. 7, 381 (2017).

Oldenburg, K. R., Vo, K. T., Ruhland, B., Schatz, P. J. & Yuan, Z. A dual culture assay for detection of antimicrobial activity. J. Biomol. Screen. 1, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705719600100305 (1996).

Kamat, N. & Velho-Pereira, S. Screening of actinobacteria for antimicrobial activities by a modified Cross-Streak method. Nat. Preced. https://doi.org/10.1038/npre.2012.6765.1 (2012).

Magaldi, S. et al. Well diffusion for antifungal susceptibility testing. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 8, 39–45 (2004). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971203000067

Chevrette, M. G. et al. The antimicrobial potential of Streptomyces from insect microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 10, 516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08438-0 (2019).

Bach, E., Volpiano, C. G., Sant’anna, F. H. & Passaglia, L. M. P. Genome-based taxonomy of Burkholderia sensu lato: distinguishing closely related species. Genet. Mol. Biol. 46, 1–13 (2023).

Kunakom, S. & Eustáquio, A. S. Burkholderia as a source of natural products. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 2018–2037 (2019).

El-Banna & Winkelmann Pyrrolnitrin from Burkholderia cepacia: antibiotic activity against fungi and novel activities against streptomycetes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00473.x (1998).

Pawar, S., Chaudhari, A., Prabha, R., Shukla, R. & Singh, D. P. Microbial pyrrolnitrin: natural metabolite with immense practical utility. Biomolecules (2019).

Ellermann, M. & Arthur, J. C. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition and modulation of host-bacterial interactions. Free Radic Biol. Med. 105, 68–78 (2017).

Kloepper, J. W., Leong, J., Teintze, M. & Schroth, M. N. Enhanced plant growth by siderophores produced by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Nature 286, 885–886 (1980).

Ahmed, E. & Holmström, S. J. M. Siderophores in environmental research: roles and applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 196–208 (2014).

Miethke, M. & Marahiel, M. A. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 413–451. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00012-07 (2007).

Sandy, M. & Butler, A. Microbial iron acquisition: marine and terrestrial siderophores. Chem. Rev. 109, 4580–4595. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9002787 (2009).

Neiendam, N. M., Jan, S., Johannes, F. & Christian, P. H. Secondary metabolite- and endochitinase-dependent antagonism toward plant-pathogenic microfungi of Pseudomonas fluorescens isolatesfrom sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3563–3569. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.64.10.3563-3569.1998 (1998).

Nagarajkumar, M., Bhaskaran, R. & Velazhahan, R. Involvement of secondary metabolites and extracellular lytic enzymes produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens in Inhibition of Rhizoctonia solani, the rice sheath blight pathogen. Microbiol. Res. 159, 73–81 (2004). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0944501304000072

Hu, J., Wang, Z. & Xu, W. Production-optimized fermentation of antifungal compounds by Bacillus velezensis LZN01 and transcriptome analysis. Microb. Biotechnol. 17, e70026. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.70026 (2024).

Hill, D. S. et al. Cloning of genes involved in the synthesis of Pyrrolnitrin from Pseudomonas fluorescens and role of Pyrrolnitrin synthesis in biological control of plant disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 78–85 (1994).

Hwang, J., Chilton, W. S. & Benson, D. M. Pyrrolnitrin production by Burkholderia Cepacia and biocontrol of Rhizoctonia stem rot of poinsettia. Biol. Control. 25, 56–63 (2002). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1049964402000440

Gondry, M. et al. Cyclodipeptide synthases are a family of tRNA-dependent peptide bond–forming enzymes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 414–420 (2009).

Kumar, N., Mohandas, C., Nambisan, B., Kumar, D. R. S. & Lankalapalli, R. S. Isolation of proline-based cyclic dipeptides from Bacillus sp. N strain associated with rhabitid entomopathogenic nematode and its antimicrobial properties. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 355–364 (2013).

Canu, N., Moutiez, M., Belin, P. & Gondry, M. Cyclodipeptide synthases: a promising biotechnological tool for the synthesis of diverse 2, 5-diketopiperazines. Nat. Prod. Rep. 37, 312–321 (2020).

Maiti, P. K. & Mandal, S. Comprehensive genome analysis of Lentzea reveals repertoire of polymer-degrading enzymes and bioactive compounds with clinical relevance. Sci. Rep. 12, 8409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12427-7 (2022).

Yan, D. et al. Discovering type I cis-AT polyketides through computational mass spectrometry and genome mining with Seq2PKS. Nat. Commun. 15, 5356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49587-1 (2024).

Paysan-Lafosse, T. et al. The Pfam protein families database: embracing AI/ML. Nucleic Acids Res. 53,, D523–534. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae997 (2025).

Jahns, C. et al. Pellasoren: structure elucidation, biosynthesis, and total synthesis of a cytotoxic secondary metabolite from Sorangium cellulosum. Angew Chemie Int. Ed. 51, 5239–5243. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201200327 (2012).

Zhou, L., Song, C., Li, Z. & Kuipers, O. P. Antimicrobial activity screening of rhizosphere soil bacteria from tomato and genome-based analysis of their antimicrobial biosynthetic potential. BMC Genom. 22, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-07346-8 (2021).

Sunithakumari, V. S., Menon, R. R., Suresh, G. G., Krishnan, R. & Rameshkumar, N. Characterization of a novel root-associated diazotrophic rare PGPR taxa, Aquabacter pokkalii sp. nov, isolated from pokkali rice: new insights into the plant-associated lifestyle and brackish adaptation. BMC Genom. 25, 424 (2024).

Babu-Khan, S. et al. Cloning of a mineral phosphate-solubilizing gene from Pseudomonas Cepacia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 972–978. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.61.3.972-978.1995 (1995).

Buch, A. D., Archana, G. & Kumar, G. N. Enhanced citric acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 by overexpression of the Escherichia coli citrate synthase gene. Microbiology 155, 2620–2629 (2009).

Gardner, S. G., Johns, K. D., Tanner, R. & McCleary, W. R. The PhoU protein from Escherichia coli interacts with PhoR, PstB, and metals to form a phosphate-signaling complex at the membrane. J. Bacteriol. 196, 1741–1752. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00029-14 (2014).

Gupta, S. & Pandey, S. ACC deaminase producing bacteria with multifarious plant growth promoting traits alleviates salinity stress in French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) plants. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01506 (2019). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/

Li, B. et al. Exogenous spermidine inhibits ethylene production in leaves of cucumber seedlings under NaCl stress. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. J. Amer Soc. Hort Sci. 138, 108–113 (2013).https://journals.ashs.org/jashs/view/journals/jashs/138/2/article-p108.xml

Xie, S. S. et al. Plant growth promotion by spermidine-producing Bacillus subtilis OKB105. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 27, 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-01-14-0010-R (2014).

Tang, J. et al. Biosynthetic pathways and functions of indole-3-acetic acid in microorganisms. Microorganisms (2023).

Klessig, D. F., Choi, H. W. & Dempsey, D. A. Systemic acquired resistance and Salicylic acid: past, present, and future. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 31, 871–888. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-03-18-0067-CR (2018).

Ryu, C. M. et al. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 4927–4932. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0730845100 (2003).

Ramos, J. L. et al. Responses of Gram-negative bacteria to certain environmental stressors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4, 166–171 (2001). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1369527400001831

Jenal, U., Reinders, A. & Lori, C. Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.190 (2017).

Dekkers, L. C. et al. Role of the O-Antigen of lipopolysaccharide, and possible roles of growth rate and of NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (nuo) in competitive tomato root-tip colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.8.763 (1998).