Abstract

Trypanosomosis is a major infectious disease affecting cattle in Sudan. In South Darfur, data on cattle trypanosomosis has been limited since the Darfur civil war (2003–2007). This study assessed the prevalence and distribution of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle in the tsetse fly endemic Al Radom National Park, and collected questionnaire data on trypanocide use and apparent efficacy. Blood from 509 cattle across four regions was analysed. Of these, 3.1%, 19.8% and 35.8% tested positive for trypanosomes by microscopy, buffy coat technique and PCR, respectively. At the regional level, prevalence was 50.0%, 42.9%, 27.3% and 22.9% in Al Radom Livestock Market, Kafindibei, Al Radom town and Murayrayah, respectively. Trypanosoma congolense savannah (15.7%), Trypanosoma vivax (9.6%), Trypanosoma brucei (0.8%) and Trypanosoma theileri (13.4%) were identified. Prevalence was significantly correlated with region and age (P < 0.05). Older cattle showed significantly higher prevalence (44.7%) than 1–3 years old (29.7%) and < 1 year old cattle (22.7%). Most cattle (86.8%) had received trypanocides within 30 days before sample collection, mainly diminazene aceturate, either alone or combined with isometamidium chloride and/or quinapyramine. Despite treatment, 30.7% were Trypanosoma-positive by PCR. In conclusion, trypanosomes are prevalent in Al Radom National Park, even in treated cattle, indicating apparent drug inefficacy, which requires further research and control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trypanosomosis is a disease caused by unicellular Trypanosoma parasites found in the blood and other tissues of vertebrates1. In cattle, in order of importance, Trypanosoma congolense, Trypanosoma vivax, Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma evansi are identified as more virulent. However, other species such as Trypanosoma theileri and Trypanosoma simiae, which primarily infects pigs but can also occur in cattle, are considered to have a lower pathogenic impact2. Genotypic characterisation of Trypanosoma species has identified various subspecies. Trypanosoma congolense has been genotyped into four subspecies, including T. congolense “forest type” (west African riverine), T. congolense “savannah type”, T. congolense “Kilifi type” and T. congolense “Tsavo type”3,4,5. Pathogenicity can vary between the subspecies, and experimental infection studies have shown differences in virulence between the T. congolense forest, savannah and Kilifi subspecies in mice and cattle, with T. congolense savannah being the most pathogenic3,4.

Trypanosoma spp. can be transmitted biologically by tsetse flies (genus Glossina), including species such as T. congolense, T. vivax, T. brucei and T. simiae. These species are known as Salivarian trypanosomes, transmitted via the saliva of tsetse flies (Glossina spp.), and are responsible for causing African Animal Trypanosomosis6. However, T. evansi is only transmitted mechanically through the mouthparts of other blood-feeding dipterans such as tabanids, Stomoxys spp., keds, mosquitoes and sand flies7. Trypanosoma theileri uses biological transmission with tabanids as intermediate hosts. In many regions, biological and mechanical transmission of Trypanosoma species co-exist in the same hosts and sometimes even involve the same vectors8.

Trypanosomosis in cattle is characterised by anorexia, weakness, fever, pale mucous membranes, weight loss, neurological symptoms and potentially death2. The resulting economic losses are estimated at $4.5 billion annually9. Subclinically infected livestock (e.g. cattle, sheep and goats) and wildlife serve as reservoirs2. The subclinical nature of symptoms and low parasite levels often complicate diagnosis via clinical observation or routine blood smears. Therefore, PCR has been proposed as a sensitive and accurate diagnostic tool, especially for subclinical cases10. However, the pan-species nested PCR targeting the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region described by Cox, et al.11 has been widely used due to its ability to distinguish all clinically important Trypanosoma species and some subspecies in a nested PCR reaction, reducing both time and cost. This technique has been used for detecting Trypanosoma species in livestock and wildlife in sub-Saharan Africa, including Sudan12,13. For robust species and subspecies identification, the use of species-specific PCRs is also crucial to produce more detailed epidemiology data. Species-specific PCRs are well established for detecting T. congolense forest type, T. congolense savannah, T. vivax, T. brucei sensu lato, T. brucei gambiense, T. evansi, T. simiae and T. theileri5,14,15,16,17,18,19.

Control measures for animal trypanosomosis include vector control, chemotherapy and breeding resistant livestock, yet the disease continues to impact livestock health and rural economies in the region1. However, for over a century, the control has depended largely on chemotherapy, particularly relying on the use of four trypanocide drugs: diminazene aceturate (Berenil), melarsamine hydrochloride (cymelarsan), quinapyramine compounds (Antrycide) and isometamidium chloride (Samorin). Their application, especially in recent years, has been associated with the development of resistance, which is reducing their effectiveness and raising concerns about future treatment options20.

Diminazene aceturate has been widely used to treat animal trypanosomosis for over 60 years. It is known for its rapid excretion and popular due to its high therapeutic index, low resistance incidence and affordability. However, its protective effect is short-lived, typically lasting up to three weeks21. Melarsamine hydrochloride is particularly effective against T. evansi in camels and other livestock. It is useful against Berenil-resistant strains, including T. evansi and T. brucei. This drug also enhances treatment outcomes when combined with other trypanocides22. Quinapyramine, a bis-quaternary ammonium compound introduced in the 1950s, is available as quinapyramine sulphate (Antrycide Sulphate) for therapeutic and quinapyramine chloride (Antrycide Prosalt) for prophylactic use. These compounds are effective against T. congolense, T. vivax and T. brucei in cattle, sheep and goats. Combined, quinapyramine chloride and sulphate offer chemoprophylactic protection for three to four months21,23. Isometamidium chloride, a derivative of homidium and part of the diminazene aceturate molecule, is also used for both preventive and therapeutic purposes24. After intramuscular administration in cattle, its prophylactic effect usually lasts two to three months, but can be extended up to six months, depending on factors like formulation, dosage, Trypanosoma species and the animal’s health23.

In Sudan, trypanosomosis has been identified in domestic ruminants using parasitological methods (such as blood smear staining and the buffy coat technique), serology and molecular approaches25,26,27,28. The pathogenic trypanosomes, T. congolense, T. vivax and T. brucei, have been found in cattle, sheep and goats, particularly near South Sudan, including in Blue Nile, East Darfur and South Darfur states. Trypanosoma evansi and T. vivax have been identified in dromedary camels26. The widespread presence of trypanosome vectors29 continues to challenge livestock farming in Sudan. South Darfur State, with an estimated 2.4 million cattle, is vital for rural livelihoods and the national economy30. However, data on animal trypanosomosis are limited, especially after the Darfur civil war (2003–2007). This study aimed to fill this gap by providing epidemiological data on Trypanosoma spp. infections in cattle at Al Radom National Park using parasitological and molecular techniques. Additionally, a questionnaire survey was conducted on the use of trypanocides in cattle in the park area.

Materials and methods

Study area

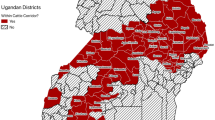

This study was conducted in Al Radom National Park (9.85°N, 24.83°E) in southwestern South Darfur State, Sudan, near the borders with South Sudan and the Central African Republic, where tsetse flies are endemic29 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The park covers about 1,250,970 hectares of high-rainfall wooded savannah. Rainfall occurs from May to November, peaking between July and September, with annual totals of 900 to 1,700 mm. Mean annual humidity ranges from 57% to 65% and temperatures vary from 16 °C to 31 °C. During the dry season (December to April), temperatures are usually below 36 °C, though some precipitation can occur31. Nomadic communities migrate to the area with their livestock during this period and may occasionally move to South Sudan towards the end of the dry season (March to May), depending on rainfall. As the rainy season begins, they migrate northward. The study focused on three different regions: Al Radom town (9.55°N, 24.59°E), Kafindibei (9.85°N, 24.49°E) and Murayrayah (9.87°N, 24.95°E).

Study animals

The study focused on indigenous Baggara cattle, an East African shorthorn zebu breed (Bos taurus indicus).

Study design, sample size and sampling strategies

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from January to February 2020 to evaluate the prevalence of trypanosomosis and to assess the use and apparent efficacy of trypanocidal drugs in cattle. Three regions were selected: Al Radom town, Kafindibei and Murayrayah. The strategy for including the region was based on the watercourse availability, forest density and livestock density. First, we selected a central point (Al Radom town) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thereafter, to avoid the factor of shared pasture shortly before sample collection, and based on nomads’ movement directions, a minimum distance of 25 km between the regions was intended. Therefore, in addition to the central point, two regions in opposite directions from Al Radom were selected: one characterised by low watercourse availability and low forest density (Murayrayah, 36 km northeast of Al Radom), and the other by high watercourse availability and high forest density (Kafindibei, 35 km southwest of Al Radom near the South Sudan border) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Kafindibei’s climate supports a higher abundance of tsetse flies compared to the other two regions29. In Al Radom, samples were collected from local farms and the Al Radom Livestock Market. The Livestock Market samples can provide information on Trypanosoma spp. in cattle from surrounding villages; however, bias in the results can be expected due to the selective nature of nomadic cattle marketing practices (e.g. animal age and health status)32.

The required sample size was calculated using Epitools epidemiological calculators33, with a confidence level of 95%, a desired precision of 0.04 and an estimated true proportion of 0.3.

The Veterinary Research Laboratory at Al Radom assisted with a nomadic guide familiar with the region and local nomadic communities. In each of the four regions, the guide provided directions to the herds, either in Al Radom town and at the Livestock Market, or at the livestock collection points at Murayrayah and Kafindibei, which are locally known as “fariq”. These points typically comprise groups of animals from various species (primarily cattle, sheep and goats) owned by a single individual or nomadic family. In each fariq (herd), cattle were selected using convenience sampling. To better manage unrestrained cattle, samples were collected in the evening (6:00 to 10:00 PM, GMT + 2), with 50% to 100% of the cattle in each fariq (herd) sampled. At the Al Radom Livestock Market, samples were collected around midday from five different herd groups, each representing one of the surrounding villages/fariqs near Al Radom.

Sample collection and processing

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein of female and male cattle. The animals, representing various age groups (< 1 year, 1–3 years and > 3 years, as classified by dentition according to Saini, et al.34, were derived from different herds (fariqs)). The distribution of samples across the study regions was as follows: 33 cattle from Al Radom town (3 herds), 38 from the Al Radom Livestock Market (5 villages/fariqs), 170 from Murayrayah (9 fariqs) and 268 from Kafindibei (10 fariqs). From each animal, 10 ml EDTA/blood was collected for direct parasitological examination and for storage at -20 °C for molecular analysis.

Questionnaire survey

A pretested semi-structured questionnaire was administered to collect data on knowledge of trypanosomosis, tsetse flies, risk factors for Trypanosoma spp. infection and the use of trypanocidal drugs (diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride, melarsamine hydrochloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride). The questionnaire also explored treatment strategies, including the use of these four drugs either alone or in combination. Interviews were conducted with nomads, each owning a distinct herd/fariq, distributed as follows: three from Al Radom town, five from the Al Radom Livestock Market, nine from Murayrayah and 10 from Kafindibei. The chemoprophylactic effectiveness of the four trypanocides is known to range from approximately 3 weeks for diminazene aceturate to 2–4 months for isometamidium chloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride21,22,23. The life cycle of Trypanosoma spp. begins when Glossina spp. inject metacyclic trypomastigotes into the animal, taking one to four weeks to complete, depending on factors such as the animal’s health35. In South Darfur State, nomads usually treat their animals, such as with anthelmintics36, every two weeks or once per month. With these three factors in mind, we used a 30-day period prior to sample collection to obtain information on the last trypanocides administered within this timeframe. This allowed us to collect data on the frequency of trypanocidal drug use and the apparent chemoprophylactic effectiveness, whether the drugs were administered alone or in combination. For diminazene aceturate and melarsamine hydrochloride, when administered alone, the 30-day period provided some information on apparent effectiveness but it can also provide data on the reinfection.

Parasitological examination for Trypanosoma spp.

Blood smears

Thin blood smears were prepared directly in the field and fixed with methanol for 5 min. In the laboratory, the smears were stained with 10% Giemsa solution for 45 min, then washed with distilled water and air-dried. The slides were examined at 1000× total magnification (oil immersion). Each sample was analysed by one of two trained laboratory technicians who meticulously examined the entire smeared area on each slide for the presence of Trypanosoma spp. following standardised protocols37.

Buffy coat technique (BCT)

The packed cell volume (PCV) of blood samples was assessed using centrifugation in glass capillaries in replicates, and then the PCV mean of each sample was calculated. Cattle with a PCV < 24% were classified as anaemic, all others were deemed non-anaemic38. Following PCV measurement, the two capillary tubes from each animal’s blood sample were examined under a light microscope at 400× magnification to identify motile trypanosomes39. Each animal was considered positive for Trypanosoma spp. if motile trypanosomes were detected in either of the two capillary tubes.

Molecular detection of Trypanosoma spp.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted using the G-spin™ Total DNA Extraction Kit, following the protocol provided by the manufacturer (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, South Korea). The DNA was eluted in 50 µl of elution buffer. The concentration and purity of the DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The DNA samples were then stored at -20 °C until further analysis.

Polymerase chain reactions

Genomic DNA samples were screened for Trypanosoma spp. using nested ITS primers as described by Cox, et al.11, using facilities available at the Bioscience Research Institute, Khartoum, Sudan. These primers amplify regions of a partial 18 S, ITS1, 5.8 S, ITS2 and a partial 28 S gene, with respective band sizes detailed in Supplementary Table 1. A nested PCR approach was used, first with outer primers ITS1 and ITS2, followed by inner primers ITS3 and ITS4 (Supplementary Table 1). PCRs were performed in 20 µl volumes containing 2 µl genomic DNA (~ 40 ng), 10 pmol primers in 20 µl of 1× PCR Master Mix (Maxime™ PCR PreMix Kit (i-MAX II), iNtRON Biotechnology) on a Bio-Rad T100 thermal cycler. The thermal profile was: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 7 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 55 °C for 60 s and extension at 72 °C for 120 s. The second PCR used 1 µl of the first-round product with inner primers ITS3 and ITS4 (Supplementary Table 1), applying the same Master Mix and cycling conditions. Second-round PCR products were analysed on 1.5% agarose gels stained with RedSafe™ Nucleic Acid Staining Solution (iNtRON Biotechnology) and visualised under ultraviolet transillumination (NuGenius, Syngene, Cambridge, UK).

Samples showing the characteristic band size for each or more of the six Trypanosoma species/subspecies11 were subjected to another round of PCR with species-specific primers according to the Supplementary Table 1. The species-specific PCRs were performed at the Institute for Parasitology and Tropical Veterinary Medicine, FU Berlin, Germany. In situations where more than one band was detected in a sample using the nested ITS primers, the corresponding Trypanosoma species at the nested ITS primers level were first identified based on the band sizes, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Then, species-specific primers were used for further confirmation of the respective Trypanosoma species. Since the band sizes for T. simiae, T. simiae Tsavo and T. theileri fall between 847 and 998 bp (nested ITS primers), any samples with bands in this range were PCR tested with both T. simiae and T. theileri species-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). Due to extensive genetic similarity between T. brucei and T. evansi40, samples showing band size corresponding to T. brucei when using nested ITS primers (1215 bp, Supplementary Table 1) were further examined by PCR using species-specific primers for T. brucei sensu lato and T. brucei gambiense, and also a species-specific primer for T. evansi (Supplementary Table 1). The PCR reactions were performed in 20 µl volumes containing 2 µl genomic DNA (~ 40 ng), 10 pmol of each primer and 10 µl of 2× GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA) on a Genetouch thermocycler (Bioer Technology, Hangzhou, China) with conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at the primer-specific annealing temperature (Supplementary Table 1) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Positive and negative controls were included in each set of reactions. The laboratory had positive control samples for T. vivax. For other Trypanosoma species (T. congolense forest type (GenBank: S50876), T. congolense savannah (GenBank: M30391), T. brucei sensu lato (GenBank: K00392), T. brucei gambiense (GenBank: FN555990), T. evansi (derived from GenBank: M81594 but slightly changed to reduce complexity and allow synthesis), T. simiae (GenBank: S50874) and T. theileri (GenBank: LC438510)), synthetic DNA fragments were used as positive controls (5 copies per reaction), paired with species-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1) to ensure sensitivity of PCR testing. These synthetic DNA fragments (G blocks) were produced by Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium). PCR products, four samples representing each Trypanosoma species, were purified using the DNA Clean & Concentrator™ kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany) and Sanger sequenced by LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany). Results were analysed using BLASTn41.

Statistical analysis

The data from the questionnaire and the survey on Trypanosoma spp. infections of cattle from four selected regions in Al Radom National Park were analysed using R software version 4.4.1 and RStudio version 2024.04.2. Descriptive statistics were performed using the summarytools package version 1.0.1 to analyse the questionnaire, PCV and prevalence data. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions in the questionnaire data and Trypanosoma spp. prevalence were calculated using Wilson score intervals via the binom.wilson() function from the epitools package version 0.5–10.1. Frequencies of positive samples and frequency of co-infections (compared to theoretical values calculated from the individual species frequencies) were compared using the mid-p exact test (Table 2by2() from epitools). To assess the agreement between the three laboratory techniques used for detecting Trypanosoma spp. infections (microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood smear, buffy coat technique and molecular technique), Cohen’s κ coefficients were calculated with the CohenKappa() function in the DescTools package version 0.99.55, with 95% CI. Interpretation of Cohen’s κ values followed McHugh42: perfect agreement (1), near perfect (0.81–0.99), substantial (0.61–0.80), moderate (0.41–0.60), fair (0.21–0.40), slight (0.0–0.20) and no agreement (< 0.0). To investigate factors affecting the prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle in Al Radom National Park, a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis was applied using the glmmTMB package (version 1.1.10)43. Both bivariable and multivariable models were used, with the exploratory variables being: study region (Murayrayah vs. Al Radom town, Al Radom Livestock Market and Kafindibei), sex (male vs. female), age (young (less than one year) vs. 1–3 years and more than three years old34, PCV (anaemic vs. non-anaemic38, and trypanocidal drug treatments (treated vs. untreated). The unique herd/fariq was included as a random effect. Moreover, factors associated with trypanocidal drug treatments were calculated using GLMM, both bivariable and multivariable models, with the variables being sex (male vs. female), age (young vs. 1–3 years and more than three years old), and PCV (anaemic vs. non-anaemic). Herd/fariq was included as a random effect. Furthermore, factors associated with PCV were also calculated using GLMM, both bivariable and multivariable models, with the variables being study region (Murayrayah vs. Al Radom town, Al Radom Livestock Market and Kafindibei), sex (male vs. female), age (young vs. 1–3 years and more than three years old), trypanocidal drug treatments (treated vs. untreated), and Trypanosoma spp. infection (non-infected vs. infected). Again, herd/fariq was included as a random effect variable. Stepwise elimination of variables was conducted using the drop1 function to minimise the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The estimates were then exponentiated and the tidy() function from the broom.mixed package (version 0.2.9.6) was applied to model coefficients to calculate the odds ratios with 95% CI. The goodness-of-fit was assessed using the conditional R² from the performance package (version 0.12.3), which estimates the proportion of variance in the response variable explained by both fixed and random factors44. Significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The samples were collected by qualified veterinarians using standard sample collection techniques, ensuring no injury or stress to the cattle. Nomads were always informed about the study’s objectives and the nature of the analyses. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Sudanese Animal Welfare Law, approved in 2015, and the study received ethical approval from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Nyala, Sudan (Reference No. UN/FVS/1/20/1). Since many of the nomads were illiterate, informed verbal consent was obtained for their participation in the study. This process was approved by the Ethics Committee. The related methods are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Results

Demographic profile of the study population and key insights from questionnaire findings

The study interviewed 27 nomads, each representing a different herd or fariq, with 5 to 53 cattle (median: 13), across four regions in Al Radom National Park: three from Al Radom town, five from the Al Radom Livestock Market, nine from Murayrayah and 10 from Kafindibei. The nomadic system was the most common husbandry practice (24/27 respondents (88.9%)) while sedentary farming was rarely used (3/27 (11.1%)) (Supplementary Table 2). The majority of respondents (24/27 (88.9%)) reported encounters between their livestock and wildlife, primarily in grazing areas. All nomads were familiar with tsetse flies (27/27 (100%)), and 51.9% had seen the fly within the six months before the interview. All 27 interviewed nomads were familiar with trypanosomosis and aware that tsetse flies are the primary vectors. The results indicated that 100% of respondents practised self-diagnosis for trypanosomosis and all of them mentioned more than two symptoms from the list provided, as explained in the Supplementary Table 2. Moreover, 100% of the respondents were aware that the use of trypanocidal drugs and the control of tsetse flies, through methods such as changing the pasture, cleaning shelters and burning dung, using smoke from wood or burning dung, and/or applying pour-on insecticides, are the main treatment and control methods for trypanosomosis (Supplementary Table 2).

The study involved 509 cattle, 6.5% in Al Radom town, 7.5% in the Al Radom Livestock Market, 33.4% in Murayrayah and 52.7% in Kafindibei. Of these animals, 55.4% were over three years old and females represented 73.1% (Table 1).

Prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. infections

The overall infection rate was 35.8% (95% CI: 31.7–40.0%) (Table 1). Cattle were considered positive for Trypanosoma spp. if they tested positive by any of the three diagnostic techniques: microscopic examination, buffy coat and molecular techniques. The infection rate among females (35.5%, 132/372) was slightly lower than in the few included males (36.5%, 50/137). Among the animal ages, cattle over three years old had the highest prevalence (44.7%), while those aged 1–3 years and younger than one year had lower rates of 29.7% and 22.7%, respectively. Prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle in Al Radom Livestock Market was 50.0% and higher compared to other regions, where prevalence ranged from 22.9% to 42.9% (Table 1). Bivariable and multivariable generalized linear mixed logistic regression models were calculated with herd/fariq included as a random effect (Table 2). The study region and age group of the animals had significant effects (P < 0.05) in both types of models on the odds of cattle being positive for Trypanosoma spp. In contrast, the variables sex, PCV and trypanocidal drug treatments were not significant (Table 2). Cattle from Al Radom Livestock Market (odds ratio: 3.500 and 3.714 for bivariable and multivariable models, respectively) and Kafindibei (odds ratio: 2.841 and 2.659 for bivariable and multivariable models, respectively) had significantly higher infection rates with Trypanosoma spp. compared to those from Murayrayah (P < 0.05). Infections were significantly more frequent in animals older than three years compared to those aged less than one year (odds ratio: 2.697 and 3.266 for bivariable and multivariable models, respectively, P < 0.001). However, the middle-aged group (1–3 years) showed non-significant P-values of 0.448 and 0.329 for bivariable and multivariable models, respectively (Table 2).

PCR, using pan-Trypanosoma primers identified a significantly (P < 0.05, mid-p exact test) higher proportion of positive samples (35.8%; 95% CI: 31.7–40.0%) compared to the buffy coat technique (19.8%; 95% CI: 16.6–23.5%) and the microscopic examination (3.1%; 95% CI: 1.9–5.1%) (Table 1). Among the three techniques, PCR and the buffy coat technique showed substantial agreement (Cohen’s κ value: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.55–0.67). In contrast, the agreement between the microscopic examination and the other two techniques was only fair to slight (Table 3).

Identification of Trypanosoma species and their prevalence based on PCR

Although the amplicon size differs between different Trypanosoma spp. in the initial ITS pan-Trypanosoma PCR (Supplementary Table 1), species assignment purely based on amplicon size was considered to be not reliable enough since the large number of potentially occurring Trypanosoma spp. made it difficult to assign a fragment unequivocally to a species. Therefore, all samples positive in the pan-Trypanosoma PCR were further analysed using species-specific primers. Additionally, selected PCR products (n = 4 for each same amplicon size) were sequenced. In total, four Trypanosoma species were identified in cattle at Al Radom National Park: T. congolense, T. vivax, T. brucei and T. theileri. The obtained sequences were 100% identical to T. vivax (GenBank HE573027), 98.0% identical to T. congolense savannah (GenBank M30391) and 100% identical to T. theileri (GenBank AB930155). However, for T. brucei, a nested pan-Trypanosoma PCR detected four bands at the expected size (1215 bp), but none of the three species-specific T. brucei primers, as well as the species-specific T. evansi primer (Supplementary Table 1), produced results. Thus, the nested pan-Trypanosoma PCR was the only method to detect T. brucei. The samples were considered positive in the following, but the results should be considered with care. Additional investigations were unfortunately not possible since the sample material was too limited.

The total prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. infections was reported at 35.8% (95% CI: 31.7–40.0%), with T. congolense savannah being the most frequent species (15.7%; 95% CI: 12.8–19.1%), followed by T. theileri at 13.4% (95% CI: 10.7–16.6%). Trypanosoma vivax was detected in 9.6% of the cattle, while T. brucei had the lowest prevalence, being detected in only four animals (Table 4). Coinfections with two Trypanosoma species, but not more, did occur in 3.7% (95% CI: 2.4–5.8%) of the animals, with coinfections of T. vivax and T. theileri being the most frequent at 2.8% (95% CI: 1.7–4.6%) (Table 4). A similar prevalence of T. congolense savannah was detected in males (15.3%) and in females (15.9%). However, female cattle showed a higher prevalence of 13.4% for T. theileri compared to 3.5% in males. Cattle over three years old exhibited 24.8% (95% CI: 20.1–30.2%) T. congolense savannah as the highest prevalence among different Trypanosoma species, compared to 5.5% and 1.6% for younger animals and 1–3 years old, respectively. Additionally, female and older cattle showed more positive cases of coinfections (Table 4). Among the four study regions, the prevalence of the four Trypanosoma species was higher in Al Radom Livestock Market compared to the other three regions, while a higher coinfection rate was found in Murayrayah (4.7%) (Table 5). For coinfections of T. vivax and T. theileri, the highest prevalence was reported in Murayrayah at 4.1% (Table 5). None of these coinfections were significantly more or less frequently found than expected from the individual prevalences of the species (mid-p exact test and correction for multiple testing using the Holm method, P > 0.05).

Insights into trypanocidal drug usage based on questionnaire data

The questionnaire analysis showed that 86.8% (95% CI: 83.6–89.5%) of the screened cattle (n = 509) had received trypanocidal drugs within the 30 days before sampling. The treatments included one or more of the following trypanocides: diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride. Melarsamine hydrochloride was not reported (Tables 1 and 6). A higher percentage of females (88.4%; 95% CI: 84.8–91.3%) received trypanocidal drugs in the 30 days before sample collection compared to males (82.5%; 95% CI: 75.3–87.9%). Within the three different age categories, the frequency of trypanocidal drug treatments practised by nomads was higher in older cattle than in younger ones, with 89.7% of cattle over three years old being treated in the last 30 days before sample collection. Among the study regions, nomads in Kafindibei treated the highest number of animals, with 268 (100%) receiving treatment during the 30 days before sample collection (Table 1). The questionnaire data also showed that 39.5% (95% CI: 35.3–43.8%) of cattle received a single trypanocidal drug, with diminazene aceturate being the most frequently administered trypanocide, used in 29.7% (95% CI: 25.9–33.8%) of all animals (n = 509), as detailed in Table 6. Nomads also practised combination trypanocidal drug treatments, using two or all three of the trypanocides. In total, 47.4% (95% CI: 43.1–51.7%) of all cattle (n = 509) received combination treatments in the 30 days before sample collection, with the diminazene aceturate-isometamidium chloride combination being the most frequently used (24.8%; 95% CI: 21.2–28.7%) (Table 6). Factors influencing trypanocidal drug treatments in the 30 days before sample collection, including sex and age of the animals, were analysed using a generalized linear mixed model with herd/fariq included as a random effect. No significant correlations were found between these factors at a P-value of < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 3).

Relationship between trypanocidal drug treatments and the occurrence of Trypanosoma spp. infections

Questionnaire data revealed that 86.8% of the 509 screened cattle had received either single or combination trypanocidal drugs within the 30 days before sample collection at Al Radom National Park. However, PCR detected that 35.8% (95% CI: 31.7–40.0%) of the tested cattle were infected with Trypanosoma spp. (Tables 1 and 6). Comparing the two results showed that 30.7% (95% CI: 26.8–34.8%) of the screened cattle were both infected with Trypanosoma spp. and had received trypanocidal drugs, while only 5.1% of Trypanosoma-positive cattle had not received trypanocides (Table 6). Unfortunately, Trypanosoma spp. were detected not only in animals that had received the curative trypanocide diminazene aceturate alone, but also in most animals treated with isometamidium chloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride, either alone or in combination, despite their known curative efficacy and long-lasting prophylactic effect (2–4 months). However, 39.3% (95% CI: 32.8–46.2%) of 201 cattle that received a single trypanocidal drug were positive for Trypanosoma spp., and 32.0% (95% CI: 26.4–38.1%) of 241 cattle that received a combination of two or all three trypanocidal drugs were also positive. Diminazene aceturate alone was administered to 151 (29.7% of the total animals), and 39.7% of these were positive for Trypanosoma spp., including single infections with T. brucei, T. congolense savannah and T. theileri, as well as coinfection with most of them. The combination treatment of diminazene aceturate and isometamidium chloride was the most frequent (24.8%, 126/509), followed by a combination of diminazene aceturate and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride (20.6%, 105/509). However, 44.4% out of the cattle that received the first combination and 20.0% of the cattle treated with the second combination were positive for Trypanosoma spp. (Table 6). Of the nine cattle that had received all three trypanocides, none tested positive for Trypanosoma spp. At the species level, T. congolense savannah and T. theileri were the most frequent Trypanosoma species, apparently surviving trypanocidal drug treatments (Table 6). A generalized linear mixed model analysis further supported the apparent trypanocidal drug treatment failure, as no significant correlation was found between treatments and Trypanosoma spp. infections (P-value > 0.05) (Table 2).

Effect of Trypanosoma spp. infections and trypanocidal drug treatments on packed cell volume

The mean PCV of all included animals was 28.8% (± 5.9% SD), classifying the animals on average as non-anaemic. Infected cattle showed a slight increase, with a mean PCV of 29.3% (± 5.9% SD) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). Across the three age groups, the PCV values were similar, with the highest mean in infected cattle aged 1 to 3 years, averaging 32.1% (± 7.0% SD). Infected cattle from Al Radom town had the highest mean PCV with 35.4% (± 7.0% SD), compared to the other three study regions (mean PCV range: 28.3–29.8%) (Table 1). The two cattle positives for T. brucei only showed the lowest mean PCV of 21.5% (± 2.1% SD), followed by a cow coinfected with T. congolense savannah and T. vivax with a PCV of 24.0% (± 0.0 SD), and then two cattle coinfected with T. brucei and T. theileri, with a PCV of 26.5% (± 9.2% SD) (Supplementary Table 4). In total, 85.7% of the animals had a normal PCV, while the rest were anaemic (PCV < 24%). The effect of trypanocidal drug treatments on the odds of having a normal PCV was also analysed using logistic regression. While animals older than three years had significantly lower odds (Odds ratio: 0.430 and 0.417 for bivariable and multivariable models, respectively) of having a normal PCV than animals below one year, a recent treatment with a trypanocide increased the odds to find a normal PCV by 5.59-fold in a multivariable model (Table 7).

Discussion

Trypanosomosis remains an economically important disease of cattle in sub-Saharan Africa, including Sudan, with the most significant impact due to infections with T. congolense, T. vivax and T. brucei2,12,25. In South Darfur State, trypanosomosis remains a frequently reported disease in cattle in veterinary clinics in tsetse fly zones and beyond, principally in the rainy season (June – October) when animals move north29,45. Nevertheless, after Darfur civil war (2003–2007), little is known about the prevalence and distribution of trypanosomosis, particularly in the tsetse fly zone such as Al Radom National Park, and data based on molecular techniques is lacking in particular.

Screening cattle for Trypanosoma spp. in Al Radom National Park revealed a prevalence of 35.8%, including single and coinfections. This is higher than previous reports in South Darfur State based on microscopic examination and/or BCT, such as 4.2%46 and 7.1%47, but lower than recent findings from other parts of Sudan that used more sensitive techniques (e.g. PCR), including Blue Nile State (56.7% and 100%) and West Kordofan (92.3%)12,25. However, the 35.8% prevalence is similar to Uganda’s 41.4%, based on ITS-PCR48, and higher than the 3.0% in Nigeria using nested ITS-PCR49 and 23.8% in Somalia using ITS-PCR50. The increase in Trypanosoma spp. prevalence over time may be due to improved detection techniques; herein, PCR identified 35.8%, compared to 19.8% with BCT and 3.1% with microscopic examination. Still, the 19.8% BCT prevalence in the present study is higher than the 4.2% reported by Hall, et al.46 using the same technique. A second factor contributing to the change in prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle in Al Radom National Park could be the Darfur civil war, which affected vector control programs. As a result, the use of trypanocidal drugs often became the only prophylactic option available, a point raised by nomads during our survey. Moreover, the independence of South Sudan in 2011 had a significant impact, as 40.7% of the interviewed nomads used to migrate to South Sudan during the dry season (March – May). Since the two regions were now in different countries, a concerted and well-managed control strategy for the whole region was no longer available. Additional factors influencing prevalence include ecological differences between the study regions, which significantly affect tsetse fly distribution and habitats29, variations in livestock husbandry51, the chances for mechanical transmission, particularly due to the abundance of tabanids7, the expansion of veterinary services21 and the use of trypanocidal/insecticidal drugs as well as the emergence of drug resistance20,52. Environmental shifts from rich to poor savannah decrease tsetse habitats, leading to an increase in the mechanical transmission of Trypanosoma species over biological transmission. This shift impacts infection types and prevalence, with poorer savannahs having lower prevalence rates29. A previous study from a semi-desert zone in Sudan, Khartoum, reported a 4.8% prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. using BCT53. This is lower than the 19.8% reported in the present study using the same technique, which indicates the impact of different environments.

PCRs identified T. congolense savannah, T. vivax, T. brucei and T. theileri in the screened cattle, with T. congolense savannah showing the highest prevalence (15.7%). This is consistent with many previous studies in South Darfur State and beyond, where T. congolense was most prevalent12,25,27,46. Coinfections, including two species, were detected in 3.7% of the animals, with the highest being T. vivax and T. theileri (2.8%). Coinfections were also detected in cattle in previous studies in Blue Nile and West Kordofan states12,25.

Risk factor analysis showed a significant correlation related to the study regions and animal age. Cattle at Al Radom Livestock Market and Kafindibei were significantly more frequently infected than those from Murayrayah. The environment in Kafindibei is rich in watercourses and forests compared to Murayrayah, supporting a favourable habitat for tsetse flies; see the atlas of tsetse flies and bovine trypanosomosis in Sudan29. The 50.0% prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle from Al Radom Livestock Market may highlight the impact of the selective nature of nomadic cattle marketing practices. Nomads usually sell adult animals rather than young ones (less than one year old) for better returns or herd replacement. Moreover, they also sell cattle with lower production values, or those that have shown frequent infection or do not respond to treatment54. The impact of human activity, particularly the Livestock Market, has been identified as a strong risk factor associated with Trypanosoma spp. infection in cattle in Tanzania (P = 0.0001)32. In the present study, cattle older than three years had significantly (P < 0.001) higher Trypanosoma spp. infections than those less than one year old. This finding aligns with many previous studies55,56,57. Previous studies indicated that calves showed higher resistance to Trypanosoma spp. infections compared to adults, as they exhibited a bone marrow response that resulted in increased erythropoiesis58,59. Additionally, calves are kept around the homestead, allowing for better care and closer monitoring for health problems. Finally, with increasing age, the animals have a higher cumulatively chance to be bitten by an infected tsetse fly and, since the infection is not cleared by the immune system, also a higher chance to be positive in the PCR.

While the questionnaire survey primarily focused on the use of trypanocidal drugs, particularly reporting the last trypanocidal drug administered within 30 days before the interview, it also highlighted nomads’ awareness of tsetse flies and trypanosomosis and its symptoms and knowledge of trypanocidal drugs. The high level of awareness underscores the significant economic impact of trypanosomosis as one of the major infectious diseases in cattle in the region. Similar findings were documented in The Gambia, Tanzania and Nigeria, where cattle breeders were aware of tsetse flies, trypanosomosis and drugs60,61,62. Nomads in Al Radom National Park reported using diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride, either alone or in combination, to treat and prevent trypanosomosis. In The Gambia, breeders mainly used diminazene aceturate and isometamidium chloride60, while those in northern Côte d’Ivoire reported using diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride and homidium bromide63.

The emergence of resistance to trypanocidal drugs poses significant challenges in controlling animal trypanosomosis. This is primarily due to various related factors, starting from inappropriate diagnosis and continuing with incorrect dosing, the use of inappropriate administration routes and issues related to drug quality from manufacturing to storage. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective management and control strategies20. In the present study, 86.8% of the cattle had received trypanocidal drugs within 30 days before the interview, highlighting the significant impact of trypanosomosis in Al Radom National Park and the need for improved control strategies. This administration rate was higher than the 50.0% reported in the same region in 198346. Increased drug affordability, awareness of trypanosomosis, changes in infection rates and increasing occurrence of drug resistance may explain this rise. A similar high usage (80.1%) of trypanocidal drugs was found in southwestern Uganda, where cattle received diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride or homidium bromide64. In Al Radom National Park, 39.5% of cattle received single-drug treatments, with diminazene aceturate being the most common (29.7%), while 47.4% received combination treatments, particularly diminazene aceturate-isometamidium chloride (24.8%). The percentage of single trypanocidal drug treatments was lower than in the Ugandan study by Kasozi, et al.64, but diminazene aceturate was similarly popular: 77.2% of surveyed farms in southwestern Uganda treated cattle with a single trypanocidal drug, particularly diminazene aceturate, in the last 30 days before questionnaire survey, and 17.0% of farms used combination trypanocidal drugs, mainly diminazene aceturate-isometamidium chloride. The high use of diminazene aceturate can be attributed to its affordability, availability, anti-inflammatory benefits and a low toxicity risk at the injection site23. The high rate of combination use in Al Radom National Park reflects nomads’ lack of confidence in single-drug efficacy, primarily due to the suspected emergence of trypanocidal drug resistance.

Data showed that 30.7% of screened cattle were treated and infected, with T. congolense savannah being the most common parasite species. This suggests apparent trypanocidal drug treatment failure, particularly the presence of drug resistance, presumably due to the high frequency of drug usage20. However, treatment failures can also have other causes than resistance, in particular underdosing, wrong application or poor quality of the drugs. Substandard veterinary drugs have been reported in sub-Saharan Africa, including Sudan36,65. Nomads often obtain veterinary drugs without a prescription or professional supervision, increasing the risk of resistance36,66. Diminazene aceturate can protect from infection for up to three weeks21. Therefore, Trypanosoma spp. positive cattle in the present study that received a diminazene aceturate treatment likely indicate a treatment failure, presumably due to a change in efficacy, although reinfection cannot be ruled out67. However, when diminazene aceturate was used in combination with isometamidium chloride and/or quinapyramine sulphate and chloride, which have a known prophylactic effect lasting 2 to 4 months23,24, the efficacy of these combinations is obviously changed in South Darfur State. The non-significant association between drug treatment and Trypanosoma spp. infections further suggest the treatment failure, and presumably the presence of resistance. A previous study in South Darfur State has reported multi-resistant trypanosomes. However, cattle receiving combination treatments including isometamidium chloride showed no Trypanosoma spp.27, supporting the use of combination therapy to extend the range of trypanocidal drug efficacy and combat resistance52. Similarly, in Kenya, combination therapy was more effective than single trypanocidal treatments68.

Anaemia remains one of the key indicators of Trypanosoma spp. infection in cattle, typically measured by PCV69. The PCV cut-off value for cattle, as defined by Mamoudou, et al.38, was used to classify screened cattle as anaemic (PCV < 24%) and non-anaemic (PCV ≥ 24%). In the present study, the mean PCV of infected and non-infected cattle was not significantly different. Remarkably, no correlation was found between infection and PCV. This was consistent with a previous study in the same region by Hall, et al.46, who did not find a correlation between the infection and the PCV. The lack of correlation was often attributed to a degree of trypanosome tolerance in Baggara cattle. In the present study, recent trypanocidal treatments resulted in a significantly lower chance of animals being anaemic. Presumably, the trypanocides were still effective enough to suppress the trypanosome density to a level that did not cause anaemia, but not enough to lead to a negative PCR result. Coinfection with other pathogens, such as Babesia spp. and Theileria spp., as well as helminth infections, in particular Haemonchus spp., cannot be ruled out as factors influencing the PCV. However, the improper diagnosis and subsequent treatment of the diseased animal relying on trypanocidal drugs only in this situation cannot achieve full curative results, and therefore, the expected health improvement, including an increase in the PCV, does not occur70.

Conclusions

In this study, we used microscopic examination, BCT and PCR to demonstrate that cattle in Al Radom National Park were generally infected with both single and coinfections of Trypanosoma species (T. congolense savannah, T. vivax, T. brucei and T. theileri), with T. congolense savannah being the most prevalent trypanosome. A questionnaire survey highlighted nomads’ awareness of tsetse flies, trypanosomosis and the drugs used for control, which are available in the local markets. The nomads recognised the association between tsetse flies and trypanosomosis, had good knowledge of the clinical signs of trypanosomosis, and practised both single and combination trypanocidal drug treatments using three drugs: diminazene aceturate, isometamidium chloride and quinapyramine sulphate and chloride. National control strategies should be activated for sustainable control of trypanosomosis and its vectors across the endemic regions in Sudan. Moreover, given that nomads migrate with their animals to South Sudan, where tsetse intensity is high, there is an obvious need for a coordinated and well-managed control strategy between both countries. Further studies are needed to confirm the presence of T. brucei, as well as studies directly investigating the efficacy of the three trypanocidal drugs and their combinations.

Data availability

The relevant information has been included in the manuscript. Data analysed for this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BCT:

-

Buffy coat technique

- ITS:

-

Ribosomal internal transcribed spacer

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCV:

-

Packed cell volume

References

Onyam, I. et al. A narrative review on trypanosomiasis and its effect on food production. Available SSRN 4831532. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4831532 (2024).

Morrison, L. J., Steketee, P. C., Tettey, M. D. & Matthews, K. R. Pathogenicity and virulence of African trypanosomes: from laboratory models to clinically relevant hosts. Virulence 14, 2150445. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2022.2150445 (2023).

Bengaly, Z., Sidibe, I., Boly, H., Sawadogo, L. & Desquesnes, M. Comparative pathogenicity of three genetically distinct Trypanosoma congolense-types in inbred Balb/c mice. Vet. Parasitol. 105, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00609-4 (2002).

Bengaly, Z. et al. Comparative pathogenicity of three genetically distinct types of Trypanosoma congolense in cattle: clinical observations and haematological changes. Vet. Parasitol. 108, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00164-4 (2002).

Masiga, D. K., Smyth, A. J., Hayes, P., Bromidge, T. J. & Gibson, W. C. Sensitive detection of trypanosomes in Tsetse flies by DNA amplification. Int. J. Parasitol. 22, 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(92)90047-O (1992).

AAT. African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT). Center for Food Security, Public Health and Institute for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, World Organisation for Animal Health & United States Department of Agriculture, 2003–2018. (2018). https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/trypanosomiasis_african.pdf. Accessed Sept 2024.

Brotánková, A., Fialová, M., Čepička, I., Brzoňová, J. & Svobodová, M. Trypanosomes of the Trypanosoma Theileri group: phylogeny and new potential vectors. Microorganisms 10, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020294 (2022).

Moloo, S. K., Kabata, J. M. & Gitire, N. M. Study on the mechanical transmission by Tsetse fly Glossina morsitans centralis of Trypanosoma vivax, T. congolense or T. brucei brucei to goats. Acta Trop. 74, 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-706X(99)00056-X (2000).

Shaw, A. P. M. et al. Mapping the benefit-cost ratios of interventions against bovine trypanosomosis in Eastern Africa. Prev. Vet. Med. 122, 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.06.013 (2015).

Ferreira, A. V. F. et al. Methods applied to the diagnosis of cattle Trypanosoma Vivax infection: an overview of the current state of the Art. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 24, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389201024666221108101446 (2023).

Cox, A. et al. A PCR based assay for detection and differentiation of African trypanosome species in blood. Exp. Parasitol. 111, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2005.03.014 (2005).

Salim, B. et al. An outbreak of bovine trypanosomiasis in the blue nile State, Sudan. Parasit. Vectors. 4, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-4-74 (2011).

Auty, H. et al. Trypanosome diversity in wildlife species from the Serengeti and Luangwa Valley ecosystems. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001828 (2012).

Majiwa, P. A. et al. Detection of trypanosome infections in the saliva of Tsetse flies and buffy-coat samples from antigenaemic but aparasitaemic cattle. Parasitol 108 (Pt 3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0031182000076150 (1994).

Nimpaye, H. et al. Trypanosoma vivax, T. congolense forest type and T. simiae: prevalence in domestic animals of sleeping sickness foci of Cameroon. Parasite 18, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2011182171 (2011).

Moser, D. R. et al. Detection of Trypanosoma congolense and Trypanosoma brucei subspecies by DNA amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol 99, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000061023 (1989).

Radwanska, M. et al. Novel primer sequences for polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Trypanosoma brucei Gambiense. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.289 (2002).

Rodrigues, A. C. et al. Cysteine proteases of Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) theileri: cathepsin L-like gene sequences as targets for phylogenetic analysis, genotyping diagnosis. Parasitol. Int. 59, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2010.03.002 (2010).

Artama, W. T., Agey, M. W. & Donelson, J. E. DNA comparisons of Trypanosoma evansi (Indonesia) and Trypanosoma brucei spp. Parasitol 104 (Pt 1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0031182000060819 (1992).

Ungogo, M. A. & de Koning, H. P. Drug resistance in animal trypanosomiases: epidemiology, mechanisms and control strategies. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 25, 100533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpddr.2024.100533 (2024).

Uilenberg, G. A field guide for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of African animal trypanosomosis. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. (1998). https://www.fao.org/4/x0413e/X0413E05.htm. Accessed 01 Oct 2024.

Berger, B. J. & Fairlamb, A. H. Properties of melarsamine hydrochloride (Cymelarsan) in aqueous solution. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38, 1298–1302. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.38.6.1298 (1994).

Giordani, F., Morrison, L. J., Rowan, T. G., De Koning, H. P. & Barrett, M. P. The animal trypanosomiases and their chemotherapy: a review. Parasitol 143, 1862–1889. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182016001268 (2016).

de Koning, H. P. Transporters in African trypanosomes: role in drug action and resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00167-9 (2001).

Mossaad, E. et al. Prevalence of different trypanosomes in livestock in blue nile and West Kordofan States, Sudan. Acta Trop. 203, 105302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105302 (2020).

Mossaad, E. et al. Trypanosoma Vivax is the second leading cause of camel trypanosomosis in Sudan after Trypanosoma evansi. Parasit. Vectors. 10, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2117-5 (2017).

Mohamed-Ahmed, M. & Rahman, A. Abdel Karim, E. Multiple drug-resistant bovine trypanosomes in South Darfur Province, Sudan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 24, 179–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02359614 (1992).

Elata, A. et al. Serological and molecular detection of selected Hemoprotozoan parasites in donkeys in West Omdurman, Khartoum State, Sudan. J. Vet. Sci. 82, 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.19-0534 (2020).

Ahmed, S. K. et al. An atlas of Tsetse and bovine trypanosomosis in Sudan. Parasit. Vectors. 9, 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1485-6 (2016).

SBAR. Statistical Bulletin for Animal Resources (SBAR) 27th edn. Ministry of Animal Resources and Fisheries, Sudan. Pages 4-14 (2018).

MAW. Meteorological authority weather – climate data. Nyala Airport Meteorological Station, Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Physical Development, Sudan. Annual report. (2019).

Nhamitambo, N. L., Kimera, S. & Gwakisa, P. Molecular identification of trypanosome species in cattle of the Mikumi human/livestock/wildlife interface areas. J. Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 3, 029. https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-3658/1510029 (2017).

Sergeant, E. Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. Ausvet. (2018). Available at: http://epitools.ausvet.com.au

Saini, A., Singh, B. & Gill, R. S. Estimate of age from teeth in dairy animals. Indian Dairym. 45, 143–145 (1992).

Krafsur, E. S. & Maudlin, I. Tsetse fly evolution, genetics and the trypanosomiases - a review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 64, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2018.05.033 (2018).

Mohammedsalih, K. M. et al. Epidemiology of Strongyle nematode infections and first report of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus in goats in South Darfur State, Sudan. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-1937-2 (2019).

Desquesnes, M. Compendium of standard diagnostic protocols for animal trypanosomosis of African origin. In OIE Reference Laboratory for Animal Trypanosomosis of African Origin. OIE/CIRAD/CIRNES (2017).

Mamoudou, A., Payne, V. K. & Sevidzem, S. L. Hematocrit alterations and its effects in naturally infected Indigenous cattle breeds due to Trypanosoma spp. On the Adamawa Plateau - Cameroon. Vet. World. 8, 813–818. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2015.813-818 (2015).

Chagas, C. R. F., Binkienė, R., Ilgūnas, M., Iezhova, T. & Valkiūnas, G. The Buffy coat method: a tool for detection of blood parasites without staining procedures. Parasit. Vectors. 13, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-3984-8 (2020).

Carnes, J. et al. Genome and phylogenetic analyses of Trypanosoma evansi reveal extensive similarity to T. brucei and multiple independent origins for dyskinetoplasty. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e3404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003404 (2015).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 22, 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031 (2012).

Brooks, M. E. et al. GlmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378–400 (2017).

Nakagawa, S. & Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x (2013).

Mohamed-Ahmed, M. M., Ahmed, A. I. & Ishag, A. Trypanosome infection rate of Glossina morsitans submorsitans in Bahr El Arab, South Darfur Province, Sudan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 21, 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02261101 (1989).

Hall, M. J. R., Kheir, S. M., Rahman, A. H. A. & Noga, S. Tsetse and trypanosomiasis survey of Southern Darfur Province, Sudan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 15, 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02242056 (1983).

Abdalla, H. S., Abdel-Gadir, F. A. & lsmail, A. A. Incidence of Bovine Trypanosomiasis in Southern Darfur (Veterinary Research Administration Report, 1977).

Angwech, H. et al. Heterogeneity in the prevalence and intensity of bovine trypanosomiasis in the districts of Amuru and Nwoya, Northern Uganda. BMC Vet. Res. 11, 255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0567-6 (2015).

Habeeb, I. F., Chechet, G. D. & Kwaga, J. K. P. Molecular identification and prevalence of trypanosomes in cattle distributed within the Jebba axis of the river Niger, Kwara State, Nigeria. Parasit. Vectors. 14, 560. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-05054-0 (2021).

Hassan-Kadle, A. A., Ibrahim, A. M., Nyingilili, H. S., Yusuf, A. A. & Vieira, R. F. C. Parasitological and molecular detection of Trypanosoma spp. In cattle, goats and sheep In Somalia. Parasitol 147, 1786–1791. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202000178X (2020).

Majekodunmi, A. O. et al. Social factors affecting seasonal variation in bovine trypanosomiasis on the Jos Plateau, Nigeria. Parasit. Vectors. 6, 293. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-293 (2013).

Morrison, L. J. et al. What is needed to achieve effective and sustainable control of African animal trypanosomosis? Trends Parasitol. 40, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2024.06.013 (2024).

Elmahi, S. M. E. O., Mahmoud, M. A. M., Yousof, A. I. A. & Elfadil, A. A. M. Prevalence and risk factors of bovine trypanosomiasis in Khartoum State, Sudan, April-July 2012. Glob J. Med. Res. 19, 25–31 (2019).

Marin, A. Between cash cows and golden calves: adaptations of Mongolian pastoralism in the age of the market. Nomadic Peoples. 12, 75–101. https://doi.org/10.3167/np.2008.12020 (2012).

Ekra, J. Y. et al. Molecular epidemiological survey of pathogenic trypanosomes in naturally infected cattle in Northern Côte d’ivoire. Parasites Hosts Dis. 61, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.3347/phd.22170 (2023).

Fesseha, H., Eshetu, E., Mathewos, M. & Tilante, T. Study on bovine trypanosomiasis and associated risk factors in Benatsemay District, Southern Ethiopia. Environ. Health Insights. 16, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786302221101833 (2022).

Tegegn, T., Tekle, O., Dikaso, U. & Belete, J. Prevalence and associated risk factors of bovine trypanosomosis in Tsetse suppression and non-suppression areas of South Omo Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. Prev. Vet. Med. 192, 105340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2021.105340 (2021).

Andrianarivo, A. G., Muiya, P. & Logan-Henfrey, L. L. Trypanosoma congolense: high erythropoietic potential in infected yearling cattle during the acute phase of the anemia. Exp. Parasitol. 82, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1006/expr.1996.0014 (1996).

Fall, A., Diack, A., Diaité, A., Seye, M. & d’Ieteren, G. D. M. Tsetse challenge, trypanosome and helminth infection in relation to productivity of village Ndama cattle in Senegal. Vet. Parasitol. 81, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00213-1 (1999).

Kargbo, A. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of livestock owners and livestock assistants towards African trypanosomiasis control in the Gambia. J. Parasitol. Res. 2022 (3379804). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3379804 (2022).

Magwisha, H. et al. Knowledge, attitude and control practices of Tsetse flies and trypanosomiasis among agro-pastoralists in Rufiji Valley, Tanzania. Commonw. Vet. Assoc. 29, 5–11 (2013).

Oluwafemi, R. Cattle ownership status, size and management systems in Lafia local government areas of Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Niger Agric. J. 39, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.4314/naj.v39i1.3277 (2008).

Ekra, J. Y. et al. Trypanocide use and molecular characterization of trypanosomes resistant to diminazene aceturate in cattle in Northern Côte d’ivoire. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 9, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9090192 (2024).

Kasozi, K. I., MacLeod, E. T., Sones, K. R. & Welburn, S. C. Trypanocide usage in the cattle belt of Southwestern Uganda. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1296522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1296522 (2023).

Mamoudou, A., Njanloga, A., Hayatou, A., Suh, P. F. & Achukwi, M. D. Animal trypanosomosis in clinically healthy cattle of North cameroon: epidemiological implications. Parasit. Vectors. 9, 206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1498-1 (2016).

Melaku, A. & Birasa, B. Drugs and drug resistance in African animal trypanosomosis: a review. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. 5, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.ejas.2013.5.3.75164 (2013).

Kasozi, K. I., MacLeod, E. T. & Welburn, S. C. African animal Trypanocide resistance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 950248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.950248 (2023).

Okello, I. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of African animal trypanosomiasis in cattle in Lambwe, Kenya. J. Parasitol. Res. 2022 (5984376). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5984376 (2022).

Marcotty, T. et al. Evaluating the use of packed cell volume as an indicator of Trypanosomal infections in cattle in Eastern Zambia. Prev. Vet. Med. 87, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2008.05.002 (2008).

Van Wyk, I. C. et al. The impact of co-infections on the haematological profile of East African Short-horn Zebu calves. Parasitol 141, 374–388. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182013001625 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the nomads in Al Radom National Park for allowing us to work on their farms (herds/fariqs) with their animals. We also thank the Veterinary Research Laboratory Office at Al Radom and Ibrahim Elsadig, the nomadic guide they provided. Our gratitude extends to the administrative staff at the University of Nyala, Sudan, as well as the dean and staff members of the Faculty of Veterinary Science for their kindness and support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded as part of Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa – Sudan (TIBA-Sudan). TIBA is an Africa-led, multidisciplinary research program commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Programme (16/136/33), utilising UK aid from the UK Government. The recipient was Prof. Maowia M. Mukhtar, the Principal Investigator. The funding supported data collection, including sustenance, transportation and the payment of research assistants. Additional support was provided by Bash Pharma, a Sudanese pharmaceutical manufacturing company (South Darfur office) and internal funds from FU Berlin. Dr. Khalid M. Mohammedsalih’s stay in Germany is funded by a scholarship co-sponsored by the Institute of International Education’s Scholar Rescue Fund (IIE-SRF) and FU Berlin. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: KMM, MMM and AB. Field trials in Sudan: KMM, AIYI, IMIM, FJ and AAA. Laboratory work: KMM, MMM, EME and JK. Data analysis: JK and KMM. Manuscript writing: KMM, GvSH and JK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammedsalih, K.M., Mukhtar, M.M., Ibrahim, A.I.Y. et al. High prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. and apparent trypanocidal drugs inefficacy in cattle in Al Radom National Park, Sudan. Sci Rep 16, 3472 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37097-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37097-7