Abstract

This paper presents the development of an innovative biomarker detection technology based on NV centres. In order to provide initial proofs of concept for the technique, we applied this detection technique to Lateral Flow Assays (LFA) through the use of NV-doped functionalised nanodiamonds (ND) as LFA labels. The remarkable properties of NV centres in diamond enable a sensitive and quantitative detection of biomarkers with an LFA label that is robust to external perturbation, easy to handle and functionalisable for a wide range of targets. The aim of NV-based LFA is to combine the advantages of the most widely used LFA - i.e. high speed, simplicity and low cost – with quantitative and highly sensitive measurements in a large detection range, from pg/mL limit of detection to mg/mL. Such detection could be of great interest in a variety of applications where simple but sensitive detection is required, for e.g. biomedical, agri-food or ecotoxicology diagnostics. NV-doped nanodiamonds have already shown promise as alternative labels in LFA, yet lack quantitative comparison with conventional markers. This study addresses this gap by validating an NV-based LFA setup for cancer antigen detection and providing a first experimental comparison with standard LFA labels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available for reasons of confidentiality related to the KWAN-TEK company but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, Y., Zhan, L., Qin, Z., Sackrison, J. & Bischof, J. C. Ultrasensitive and Highly Specific Lateral Flow Assays for Point-of-Care Diagnosis. ACS Nano 15, 3593. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c10035 (2021).

Grant, B. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Nucleocapsid Antigen-Detecting Half-Strip Lateral Flow Assay Toward the Development of Point of Care Tests Using Commercially Available Reagents Anal. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 11305. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01975 (2020).

Koczula, K. M. & Gallotta, A. Lateral flow assays Essays in Biochemistry 60, 111. https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20150012 (2016).

Bahadır, E. B. & Sezgintürk, M. K. Lateral flow assays: Principles designs and labels. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 82, 286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2016.06.006 (2016).

Solin, K. et al. Immobilized cellulose nanospheres enable rapid antigen detection in lateral flow immunoassays. Cellulose 30, 2353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-022-05038-y (2023).

Choi, J.R. Development of Point-of-Care Biosensors for COVID-19 Front. Chem. (2020), publisher: Frontiershttps://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2020.00517

Feng, W. et al. Molecular Diagnosis of COVID-19: Challenges and Research Needs Anal. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 10196. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02060 (2020).

Udugama, B. et al. Diagnosing COVID-19: The Disease and Tools for Detection ACS Nano. Am. Chem. Soc. 14, 3822. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c02624 (2020).

Loo, J. F. C., Ho, A. H. P., Turner, A. P. F. & Mak, W. C. Integrated Printed Microfluidic Biosensors Trends in Biotechnology. Elsevier 37, 1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.03.009 (2019).

Jiang, T. et al. O157:H7 using Pt–Au Sensitive detection of Escherichia coli bimetal nanoparticles with peroxidase-like amplification. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 77, 687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2015.10.017 (2016).

Cho, I.-H., Das, M., Bhandari, P. & Irudayaraj, J. High performance immunochromatographic assay combined with surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Sensors and Actuators B: Chem. 213, 209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2015.02.091 (2015).

Parolo, C., de la Escosura-Muñiz, A. & Merkoçi, A. Selected Papers from the World Congress on Biosensors Biosensors and Bioelectronics Selected Papers from the World Congress on. Biosensors 40, 412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2012.06.049 (2013).

Sena-Torralba, A., Álvarez Diduk, R., Parolo, C., Piper, A. & Merkoçi, A. Toward Next Generation Lateral Flow Assays: Integration of Nanomaterials. Am. Chem. Rev. Soc. 122, 14881. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c01012 (2022).

Mousseau, F. et al. Luminescent lanthanide nanoparticle-based imaging enables ultra-sensitive, quantitative and multiplexed in vitro lateral flow immunoassays Nanoscale. Royal Soc. Chem. 13, 14814. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NR03358A (2021).

Wang, X., Wu, X., Lu, Z. & Tao, X. Biomolecules 10, Comparative Study of Time-Resolved Fluorescent Nanobeads, Quantum Dot Nanobeads and Quantum Dots as Labels in Fluorescence Immunochromatography for Detection of Aflatoxin B1 in Grains. Multidisciplinary Digital Publ. Institute (MDPI) https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040575 (2020).

Luo, K., Hu, L., Guo, Q., Wu, C., Wu, S., Liu, D., Xiong, Y., Lai, W. Journal of Dairy Science 100, 5176 ( 2017), https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-12554,publisher: Elsevier

Hu, L.-M., Luo, K., Xia, J., Xu, G.-M., Wu, C.-H., Han, J.-J., Zhang, G.-G., Liu, M., Lai, W.-H. Advantages of time-resolved fluorescent nanobeads compared with fluorescent submicrospheres, quantum dots, and colloidal gold as label in lateral flow assays for detection of ractopamine Biosensors and Bioelectronics 91, 95 ( 2017)https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2016.12.030

Zhao, S., Zhao, S., Guo, Y. Time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay for detection of CEA in salivain Advances in Food Safety and Environmental Engineering ( CRC Press, 2022) num Pages: 9

Jin, B., Du, Z., Zhang, C., Yu, Z., Wang, X., Hu, J., Li, Z. Eu-Chelate Polystyrene Microsphere-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay Platform for hs-CRP Detection Biosensors 12, 977 ( 2022), number: 11 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institutehttps://doi.org/10.3390/bios12110977

Chen, K. et al. A Rapid and Sensitive Europium Nanoparticle-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay Combined with Recombinase Polymerase Amplification for Simultaneous Detection of Three Food-Borne Pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18, 4574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094574 (2021).

Liang, R.-L. et al. Europium (III) chelate microparticle-based lateral flow immunoassay strips for rapid and quantitative detection of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. Sci Rep. 7(1), 14093. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14427-4 (2017).

Zhou, S. et al. Ultrasensitive Point-of-Care Test for Tumor Marker in Human Saliva Based on Luminescence-Amplification Strategy of Lanthanide Nanoprobes. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 8, 2002657. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202002657 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Europium chelate-labeled lateral flow assay for rapid and multiple detection of \(\beta\)-lactam antibiotics by the penicillin-binding protein. Anal. Methods 12, 3645. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0AY01140A (2020).

Song, Z. et al. NIR-II fluorescent nanoprobe-labeled lateral flow biosensing platform: A high-performance point-of-care testing for carcinoembryonic antigen. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 224, 115063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2023.115063 (2023).

Thomas DeCruz, A. et al. Quantum-enhanced nanodiamond rapid test advances early SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection in clinical diagnostics. Nat Commun 16, 8778. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63066-1 (2025).

Huang, D. et al. Towards ultra-sensitive and rapid near-source wastewater-based epidemiology. Nat. Commun. 16, 8158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63192-w (2025).

Angela, S., Hsiao, W.W.-W., Fadhilah, G., Le, T.-N. & Chiang, W.-H. Detection of avian influenza virus utilizing fluorescent nanodiamonds for lateral flow immunoassay enhanced by magnetic modulation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 169, 105945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2024.105945 (2025).

Hsiao, W.W.-W. et al. Diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease using fluorescent nanodiamond-based spin-enhanced lateral flow immunoassay. Microchem. J. 205, 111315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2024.111315 (2024).

Le, T.-N., Chen, H.-Y., Lam, X. M., Wang, C.-C. & Chang, H.-C. Antibody-Conjugated Nanodiamonds as Dual-Functional Immunosensors for In Vitro Diagnostics. Anal. Chem. 95, 12080. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c02112 (2023).

Wei-Wen Hsiao, W. et al. Fluorescent nanodiamond-based spin-enhanced lateral flow immunoassay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and spike protein from different variants Analytica. Chimica. Acta 1230, 340389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2022.340389 (2022).

Le, T.-N. et al. Spin-Enhanced Lateral Flow Immunoassay for High-Sensitivity Detection of Nonstructural Protein NS1 Serotypes of the Dengue Virus Anal. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 17819. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c03521 (2022).

Hui, Y. Y. et al. Magnetically Modulated Fluorescence of Nitrogen-Vacancy Centers in Nanodiamonds for Ultrasensitive Biomedical Analysis. Am. Anal. Chem. Soc. 93, 7140. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01224 (2021).

Miller, B. S. et al. Spin-enhanced nanodiamond biosensing for ultrasensitive diagnostics. Nature 587(7835), 588–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2917-1 (2020).

Rondin, L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 056503. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/77/5/056503 (2014).

Doherty, M. W., Manson, N. B., Delaney, P. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. The negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond: the electronic solution New. J. Phys. 13, 025019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/13/2/025019 (2011).

Childress, L. & Hanson, R. Diamond NV centers for quantum computing and quantum networks. MRS Bulletin 38, 134. https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs.2013.20 (2013).

Rovny, J. et al. Nanoscale diamond quantum sensors for many-body physics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-024-00775-4 (2024).

Xu, Y., Zhang, W., Tian, C. Recent advances on applications of NV magnetometry in condensed matter physics Photon. Res., PRJ 11, 393 ( 2023), publisher: Optica Publishing Grouphttps://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.471266

Belser, S., Hart, J., Gu, Q., Shanahan, L. & Knowles, H. S. Opportunities for diamond quantum metrology in biological systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 020501. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0147469 (2023).

Wu, Y. & Weil, T. Recent Developments of Nanodiamond Quantum Sensors for Biological Applications. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200059. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202200059 (2022).

Qureshi, S. A. et al. Recent Development of Fluorescent Nanodiamonds for Optical Biosensing and Disease Diagnosis. Biosensors 12(12), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12121181 (2022).

Nie, L. et al. Quantum monitoring of cellular metabolic activities in single mitochondria. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf0573. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abf0573 (2021).

Tetienne, J.-P. et al. Magnetic-field-dependent photodynamics of single NV defects in diamond: an application to qualitative all-optical magnetic imaging New. J. Phys. 14, 103033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/10/103033 (2012).

Zhao, L. et al. A fluorescent biosensor based on molybdenum disulfide nanosheets and protein aptamer for sensitive detection of carcinoembryonic antigen. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 273, 185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.06.004 (2018).

Gu, X., She, Z., Ma, T., Tian, S. & Kraatz, H.-B. Electrochemical detection of carcinoembryonic antigen. Biosensors Bioelectron. 102, 610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2017.12.014 (2018).

Grunnet, M., Sorensen, J. B. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer Lung Cancer 76, 138 ( 2012)https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.012

Cavalera, S. et al. Investigation of the Antigen Hook Effect in Lateral Flow Sandwich Immunoassay: The Case of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Detection. Biosensors 12, 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12090739 (2022).

He, G., Dong, T., Yang, Z. & Jiang, Z. Mitigating hook effect in one-step quantitative sandwich lateral flow assay by timed conjugate release. Talanta 240, 123157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123157 (2022).

Ross, G. M. S., Filippini, D., Nielen, M. W. F. & Salentijn, G. I. Unraveling the Hook Effect: A Comprehensive Study of High Antigen Concentration Effects in Sandwich Lateral Flow Immunoassays. Anal. Chem. 92, 15587. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c03740 (2020).

Rey, E. G., O’Dell, D., Mehta, S. & Erickson, D. Mitigating the Hook Effect in Lateral Flow Sandwich Immunoassays Using Real-Time Reaction Kinetics. Anal. Chem. 89, 5095. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00638 (2017).

Cumberland, W. N. et al. Nonlinear Calibration Model Choice between the Four and Five-Parameter Logistic Models. J. Biopharm. Stat. 25, 972. https://doi.org/10.1080/10543406.2014.920345 (2015).

BioDot AirJet™ Dispensing, https://www.biodot.com/news-resources/biodot-airjet-tm-dispensing https://www.biodot.com/news-resources/biodot-airjet-tm-dispensing

Melo, L. L. L. S., Castro, G. P. J., Navarro, M., Gonçalves, S. M. C. & Simas, A. M. Unmasking the UV Photobleaching of \(\beta\)-Diketonate [Eu(BTFA)4]? Complexes as an Energy-Driven Photoreduction Process. Inorg. Chem. 64, 3842. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c05014 (2025).

Danthanarayana, A. N., Brgoch, J. & Willson, R. C. Photoluminescent Molecules and Materials as Diagnostic Reporters in Lateral Flow Assays ACS. Appl. Bio Mater. 5, 82. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.1c01051 (2022).

Hötzer, B., Medintz, I. L. & Hildebrandt, N. Fluorescence in Nanobiotechnology: Sophisticated Fluorophores for Novel Applications. Small 8, 2297. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201200109 (2012).

Tallaire, A., Achard, J., Silva, F., Brinza, O. & Gicquel, A. Crystal growth / Croissance cristalline Comptes Rendus Physique Crystal growth / Croissance cristalline 14, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crhy.2012.10.008 (2013).

Wang, Q. et al. Stable and Highly Fluorescent Europium(III) Chelates for Time-Resolved Immunoassays. Inorg. Chem. 52, 8461. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic400384f (2013).

Bünzli, J.-C.G. Lanthanide Luminescence for Biomedical Analyses and Imaging. Chem. Rev. 110, 2729. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900362e (2010).

Juntunen, E., Myyryläinen, T., Salminen, T., Soukka, T. & Pettersson, K. Performance of fluorescent europium(III) nanoparticles and colloidal gold reporters in lateral flow bioaffinity assay. Anal. Biochem. 428, 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2012.06.005 (2012).

Philip, J. & Carlsson, K. Theoretical investigation of the signal-to-noise ratio in fluorescence lifetime imaging. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A JOSAA 20, 368. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.20.000368 (2003).

Härmä, H., Soukka, T. & Lövgren, T. Europium Nanoparticles and Time-resolved Fluorescence for Ultrasensitive Detection of Prostate-specific Antigen. Clinical Chem. 47, 561. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/47.3.561 (2001).

Adámas Nano, https://www.adamasnano.com/ Official website of adámas nano, https://www.adamasnano.com/

Gupta, A., Hacquebard, L. & Childress, L. Efficient signal processing for time-resolved fluorescence detection of nitrogen-vacancy spins in diamond. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B JOSAB 33, 28. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.33.000B28 (2016).

Rondin, L. Réalisation d’un magnétomètre à centre coloré NV du diamant, Réalisation d’un magnétomètre à centre coloré NV du diamant These de doctorat, Cachan, Ecole normale supérieure ( 2012)https://www.theses.fr/2012DENS0065

Yang, Q. et al. Quantitative determination of major capsaicinoids in serum by ELISA and time-resolved fluorescent immunoassay based on monoclonal antibodies. Biosens Bioelectron. 81, 229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2016.02.074 (2016).

Zhang, F. et al. Lanthanide-labeled immunochromatographic strips for the rapid detection of Pantoea stewartii subsp. Stewartii Biosens Bioelectron 51, 29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2013.06.065 (2014).

Poly-Dtech, https://poly-dtech.com/ Officialwebsite of poly-dtech

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Emmanuel Pépin and Maël Raude for scientific insights to this project, Bénédicte Shevchenko, Morgane Le Guevello and Etienne Ebabe Elle for participation in the search for use cases for NV-based LFA, and Guillaume Payet for his contribution to the prototype design. We thank Loïc Charbonnière for the fruitful discussions on the use of europium nanoparticles for LFA and Huan-Cheng Chang and his team for the preliminary discussions. The authors would also like to thank the BPI France Deeptech project ‘EVADIA-FND’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BV wrote the main text of the manuscript, prepared the figures and wrote the appendices. BV, FS and SC carried out the experiments on CEA biomarker detection. BV and AP carried out the experiments on VHS/G57 detection for the comparative study. FG provided scientific advice, particularly for the LFA aspect of the various experiments. DR, TH, AB-N, and RG supervised the experiments and participated in the search for use cases and funding for the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Appendices

Appendices

A. Functionalisation protocol of nanodiamonds

The ND, used to detect CEA and VHS/G57 protein, were provided by Adámas Nanotechnologies62 and have a diameter of 100 and 300 nm respectively, with a doping in NV centres of 3 ppm. Before the bioconjugation of DAb on the ND surface, the ND surface must be prepared to activate the carboxyl (COOH) groups, allowing them to react with the amine (NH2) groups of the antibodies or of the linker molecule. To this end, 1.0 mg of ND, 2.2 mg of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 2.5 mg of sulfo-NHS (N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide) were added in MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) buffer (0.01M, pH5.0). The mixture was sonicated for 1 min in sonication bath and kept under magnetic stirring at 650 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant discarded and replaced by KPB (potassium phosphate buffer) (0.01M, pH8.0). We use bio-compatible PEG (polyethylene glycol) polymers as linker molecule grafted to the ND surface, to improve stability and reduce ND aggregation. To do so, 4.0 mg of NH2-PEG10-COOH was added to the suspension and kept it under magnetic stirring at 700 rpm overnight and room temperature. At the end, the suspension is washed with MES buffer (0.01M, pH5.0) three times. The NH2 terminated PEG polymers were linked with the activated COOH groups of the ND via an amide bond to form the ND-PEG-COOH complex. The zeta potential of the ND surface is measured (Malvern zetasizerNano ZSP instrument) at -30.7 mV after PEG functionalisation (pH \(\approx 5.5\)). The negative surface charge of ND confirms the presence of a significant amount of COOH groups at the ND-PEG surface.

Then, 0.9 mL of previously prepared ND-PEG-COOH suspension, 1.8 mg EDC and 2.2 mg sulfo-NHS were added for PEG carboxyl activation step. The suspension was kept under 650 rpm magnetic stirring for 1 h at room temperature. The suspension was washed with KPB buffer (0.01M, pH8.0) three times and then the right amount of Ab was added to get a conjugation ratio of 1:0.2 (ND:Ab). After 4 h of magnetic stirring at room temperature, BSA (bovine serum albumin) was added to the mixture in order to reach 1.5 wt% final weight percentage and kept under 650 rpm of magnetic stirring for 2h30 at room temperature. The NH2 group of the DAb will bind to the activated COOH groups of the ND-PEG-COOH complex. The final suspension was washed with KPB (0.01M, pH7.4) and 0.5wt% BSA, to finally obtain the ND-DAb complex.

Finally, the functionalised ND-DAb solution is characterised. Fourier transform InfraRed (FTIR) spectra (IRSpirit-T, Shimadzu) proves DAb grafting though the presence of two characteristic band of amide groups at 1500 and 1600 cm−1 wavenumber. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements (Zetasizer Pro, Malvern Panalytical) show an increase in the hydrodynamic size of ND of about 10 nm and 140 nm after PEG and DAb functionalisation respectively. For DAb quantification, a calibration curve was established using the colorimetric bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA). The BCA assay quantifies the proteins in solution by measuring the absorbance at 562 nm of a complex, formed by the reduction of Cu2+ ions to Cu+ by proteins (the DAb in this case). The absorbance is quantified by UV-Visible spectroscopy (FLUOstar Omega, BMG LABTECH). The quantification of DAb in the solutions, both before and after its conjugation onto the ND surface, allows for the estimation of the grafting rate, i.e. the amount of DAb linked to the ND surface. Based on these measurements, we estimate a grafting rate of around 600 Ab/ND for the 100 nm diameter ND used for the CEA detection, and 450 Ab/ND for the 300 nm ND used for the VHS/G57 detection.

B. Migration buffers

KPB (potassium phosphate buffer) or PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) maintain a buffered environment with a stable pH and ionic concentration, robust to external disturbance. The pH of these buffers corresponds to the physiological pH of 7.4. This is important to ensure that biomolecular interactions, such as antigen-antibody binding, are and remain effective throughout the assay, minimising the impact of external chemical variations that could compromise these reactions. The proteins BSA (bovine serum albumin) or casein is added to these buffers. These proteins saturates the non-specific sites on the ND surface and on the nitrocellulose membrane to avoid aspecific binding between them, thus reducing the aspecific signal (the background noise) and maximising the specific signal (as more ND will be able to bind to the TL and CL). In our case, we also added Tween20 surfactant to the buffer to disperse the assay reagents (ND, proteins, antigens etc.) and minimize non-specific interactions by reducing adhesion between functionalised ND with the nitrocellulose membrane, as well as sucrose to maintain the biological activity of the antibodies by maintaining their three-dimensional structure.

C. Methodology for LFA parameters optimisation

The underlying experimental principle of this optimisation step is to perform the migration of a liquid sample along the strip after depositing a fixed concentration of the target biomarker. In the optimisation experiments presented here, the CEA cancer antigen was detected at a concentration of 100 ng/mL. It is important to note that the optimised LFA parameters obtained in this study are therefore specific to CEA detection and would need to be re-optimised for other biomarkers. Nonetheless, this optimisation protocol provides a useful framework and an initial reference point for selecting parameters when targeting different biomarkers.

The optimal LFA parameters are those that meet the following objectives:

Maximise the specific signal. The specific signal corresponds to the fluorescence signal from the ND in the TL.

Minimise the aspecific signal. The aspecific signal corresponds to the fluorescence from ND distributed across the nitrocellulose membrane outside the TL and CL. This signal reflects the loss of ND during migration, which reduces the amount of specific signal.

The parameters evaluated in this study are listed below. For each parameter, the range of tested values is indicated, and the optimal value is highlighted in bold.

Three types of Millipore nitrocellulose membranes: HF90+, HF120+ and HF180+ (high flow). And one type of Cytiva membrane: FF120HP+.

Two types of Ahlstrom-Munksjö conjugate pad: grade 6614 and 8980.

The mass of CAb deposited in the TL in the range 1-2 \(\upmu\)g \(\rightarrow\) 2 \(\upmu\)g chosen.

Different combinations of clone numbers for the DAb/CAb Anti-CEA pair: DAb [5909], DAb [5010], CAb , CAb .

The size of ND in the range 70-300 nm \(\rightarrow\) 100 nm chosen.

The mass of ND deposited in the range 10–1000 ng \(\rightarrow\) 350 ng chosen.

The grafting rate of DAb on ND in the range 100-1000 DAb per ND \(\rightarrow\) 600 DAb per ND chosen.

The composition and volume of the migration buffer \(\rightarrow\) 50 \(\upmu\)L of buffer composed of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and Tween 20 (appendix B).

The composition and volume of the diluent conjugate buffer \(\rightarrow\) 2 \(\upmu\)L of conjugate buffer diluent composed of potassium phosphate buffer (KPB), bovine serum albumin (BSA), sucrose and Tween 20 (appendix B).

The antibodies Anti-CEA used were obtained from Medix Biochemica under the following references: Anti-h CEA 5909 SP-5 (Cat. Number: 100428) and Anti-h CEA 5910 SPTN-5 (Cat. Number: 100047). Both antibodies are mouse monoclonal IgG1 specific for human CEA. Anti-h CEA 5909 SP-5 (clone number ) has an affinity constant of \(3 \times 10^{10}~\textrm{M}^{-1}\) and is mapped to epitope group C, whereas Anti-h CEA 5910 SPTN-5 (clone number ) has a higher affinity constant of \(1 \times 10^{11}~\textrm{M}^{-1}\), with its epitope not disclosed.

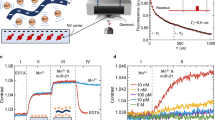

D. NV-based LFA reader prototype

The Fig. 4 shows a photograph of a first overview of our NV-based LFA reader prototype. Once integrated, the reader should contain the laser, the photodetector and the optics for exciting the NV centres and collecting their fluorescence, the electromagnet for optical modulation of the fluorescence, a motor for automatic scanning of the strip, and the associated electronic cards. By inserting the cassette containing the LFA strip, after having done the migration, the reader will automatically read the quantity of biomarkers along the strip point by point. The prototype shown in the Fig. 4 is not functional; it contains the various sub-systems, confirming the prototype’s dimensions, but the electronic boards still need to be developed. We eventually aim for these results to support the future commercialisation of the NV-based LFA for concrete diagnostic applications. Accordingly, preliminary selling prices were estimated. Current projections suggest pricing comparable to existing quantitative LFA: €500-€1,000 for the reader after scaling and from one to a few euros for the LFA strip, depending on the biomarker and the number of tests. Indeed, none of the components of either the NV-based LFA reader or the strip represent major cost drivers or have significant supply constraints.

a Photograph of the plastic cassette containing the LFA strip. ND functionalised against the targeted biomarker are first deposited on the conjugate pad of the strip. The liquid sample to be tested is deposited at the beginning of the strip (sample pad), indicated by the black arrow. b Photograph of a first overview of an NV-based LFA reader prototype, with an aluminium casing.

E. Photophysic calculations for NV centres and europium molecules

We present here a simplified model to estimate the order of magnitude of optical signals emitted by diamond NV centers and europium molecules, based on their respective photophysical properties and under the most comparable conditions possible. The aim of this model is to compare their optical detection limits on a relative scale. To this end, we evaluate the noise-equivalent power (NEP). The NEP, in W\(/\sqrt{\textrm{Hz}}\), is defined as the optical power required to achieve a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) equal to one over a bandwidth of one hertz. In other words, the NEP represents the minimum optical power that can be detected above the background optical noise.

The NEP of NV centres can first be estimated and is defined by:

where \(P_{\textrm{NV, useful}}\) is the power of the useful optical signal emitted by the NV centres, and \(\delta P_{\textrm{NV}}\) the noise of this signal (both in W).

\(P_{\textrm{NV, useful}}\) represents the portion of the signal that contributes to biomarker detection. It corresponds to the amount of the quenching optical signal collected by the photodetector, through the optical setup. It is indeed this quenching signal, blinking at 120 Hz and represented on Fig. 1d of the main text, that enables the optical detection of biomarkers. \(P_{\textrm{NV}}\) is the total optical power measured by the photodetector, including the optical signal from the NV centres plus from the background noise, and q is the percentage of quench of this signal. According to the literature, it is possible to quench the fluorescence of the NV centre by a value of \(q = 54 \%\) of the fluorescence without quenching43,63. Thus:

with \(T_{\textrm{NV}}\) the total transmission of the optical setup, from the ND to the photodetector. As the NEP is defined as the optical signal \(P_{\textrm{NV}}\) leading to SNR\(_{\textrm{NV}} = 1\), and by replacing (3) in (2), it can therefore be expressed as :

The noise \(\delta P_{\textrm{NV}}\) of the NV centres optical signal, in W\(/\sqrt{\textrm{Hz}}\), is measured by performing the Power Spectral Density (PSD, in dBV2/Hz) of this signal using Welch’s method:

The resulting PSD is presented in Fig. 5a. The noise limit PSD\(_{\textrm{NV}}\) = − 90 dBV2/Hz corresponds to the floor of the PSD. The ND optical measurement is therefore limited by the fundamental shot noise, due to the discrete nature of photons. This noise, in dBV2/Hz, is defined by:

with \(\delta V\) the noise of the electrical signal collected by the photodetector from the NV fluorescence (in V), G the photodetector gain (in V/W) and \(\delta P\) the noise of the corresponding optical signal before photoelectric conversion of the photodetector (in W). The value of the optical shot noise can be expressed as a function of the PL collected, leading to:

with h the Planck constant (in J.s), c the speed of light (m/s), \(\lambda\) the wavelength of the PL collected (m) and P its optical power (W). The optical signal detected by the photodetector in our ND-based LFA set-up, whose PSD is plotted on Fig. 5a, is of 2.2 nW, leading to PSD(\(S_{\textrm{NV}}\)) \(\approx\) -90 dBV2/Hz. From (5), we have:

Substituting (8) into (4), we obtain:

a Power Spectral Density (PSD) of NV-doped ND fluorescence (in blue) and of the MPPC photodetector, without optical input signal (in green). The PSD, in dBV2/Hz, represents how the power of an optical signal, collected by the photodetector, is distributed across different frequency components. The flat spectral floor sets the fundamental noise limit on the measurement. The PSD in blue was obtained on ND bound in the TL after the migration and under magnetic modulation. We observe the NV fluorescence blinking at 120 Hz, as well as the first 3 harmonics (240, 360 and 480 Hz), and the shot noise limit at PSD\(_{\textrm{NV}}\) \(\approx\) − 90 dBV2/Hz. The PSD measured from the MPPC signal (in green) indicates the noise limit of the photodetector at PSD\(_{\textrm{MPPC}}\) \(\approx\) − 122 dBV2/Hz. b Evolution of the normalised fluorescence emitted by an europium molecule after its optical excitation. We consider a long fluorescence time of \(\tau _{\textrm{Eu}}~=~1~\textrm{ms}\), with a measurement of time \(\Delta t = 400~\mathrm {\mu s}\) performed at \(T_0 = 200~\mathrm {\mu s}\).

In the measurements carried out on our experimental bench, the excitation laser power, of few mW before the focusing lens on the strip (Fig. 1 of the main text), is sufficient to saturate the NV centres64. An NV centre therefore emits a photon of energy \(E_{\textrm{NV}} = \frac{hc}{\lambda _{\textrm{NV}}}\), with \(\lambda _{\textrm{NV}}=680\) nm, on average every \(\tau _{\textrm{NV}}=12\) ns34 at optical saturation. We can thus write:

In order to be able to compare the NEP obtained with NV centres and with europium molecules, these NEP are expressed in units of LFA labels. In the case of NEP\(_{\textrm{NV}}\), the LFA labels are the NV-doped ND. Thus:

with \(N_\textrm{NV}\) the number of NV centres per ND.

Similarly to (2), NEP\(_\textrm{Eu}\) is defined, in \(W/ \sqrt{Hz}\), as the optical power needed to obtain:

To estimate NEP\(_\textrm{Eu}\), certain assumptions about europium are made in order to fully exploit the properties of europium molecules and to make a relevant comparison with the NEP\(_\textrm{NV}\) estimation. It is assumed that the optical detection of europium luminescence is carried out under the best possible conditions, taking advantage of the long fluorescence time of europium molecules \(\tau _\textrm{Eu}\) of one to few ms15,60. To do this, the europium luminescent is detected by time-resolved fluorescence15,16,17,18,19,20,21,57,65,66. The principle of this measurement is to wait for a delay \(T_0\) before taking the measurement of an acquisition time \(\Delta t\). The parasitic signal from the background decreases rapidly over time, while europium have a longer fluorescence time, during which they continue to emit luminescence in a decreasing trend, as shown in Fig. 5b. A time-resolved measurement can therefore be used to detect the useful signal with a very good SNR, once the background interference signal has diminished rapidly over time. We can therefore deduce:

with \(T_{\textrm{Eu}}\) the total transmission of the optical setup, from the Eu molecules to the photodetector. We assume that the same optical setup is used to detect NV centres and Eu molecules, thus \(T_{\textrm{Eu}} = T_{\textrm{NV}} = T\). The parameter \(\eta\) corresponds to the percentage of europium luminescence, represented on Fig. 5b, collected after a waiting time \(T_0\) and during an acquisition time \(\Delta t\). The numerical value of \(\eta\) depends on the parameters \(\tau _{\textrm{Eu}}\), \(T_{0}\) and \(\Delta t\).

By replacing (13) in (12), and by definition of \(\textrm{NEP}_{\textrm{Eu}}\), it can therefore be expressed as:

In the absence of further information regarding europium luminescence detection, it is assumed that the signal is collected using one of the most sensitive photodetectors available on the market, the same type employed for NV center detection (i.e. Multi-Pixel Photon Counter, MPPC). We therefore assumed that the low MPPC measurement noise is the limiting noise for europium detection. The europium detection noise can therefore be written as \(\textrm{PSD}(\delta V_\textrm{Eu}) = \textrm{PSD}(\textrm{MPPC}) \approx -122~\textrm{dBV}^2/\textrm{Hz}\), with the MPPC used in the experiments presented here (Fig. 5a). With this assumption, we therefore assume a lower detection noise, in favour of europium, than the one measured experimentally on the NV centres: PSD\(_{\textrm{NV}}\) \(\approx\) − 90 dBV2/Hz. As for (8), the optical noise on europium detection is expressed as:

in W/\(\sqrt{(}Hz)\). We replace \(\delta P_\textrm{Eu}\) in (14):

As mentioned above for the estimation of \(NEP_\textrm{NV}\), both NEP should be expressed in units of LFA labels in order to compare them. An europium molecule emits a photon of energy \(E_{\textrm{Eu}} = \frac{hc}{\lambda _\textrm{Eu}}\), with \(\lambda _\textrm{Eu} \approx 615\) nm16,17,18,57,65,66, every \(\Delta T_{\textrm{acq}}\). \(\Delta T_{\textrm{acq}}\) represents the minimum time between two excitations of an europium molecule, and therefore between the successive emission of two europium photons. In practice, this is limited by the excitation rate of the flash lamp used to excite the europium molecules. We consider \(\Delta T_{\textrm{acq}} \approx 5~\textrm{ms}\) using realistic excitation rates67. In the case of NEP\(_\textrm{Eu}\), the LFA labels are the nanoparticles carrying europium molecules. We denote \(N_\textrm{Eu}\) as the number of luminescent europium molecules per nanoparticle. Thus:

As the NEP\(_\textrm{NV}\) and NEP\(_\textrm{Eu}\) are both expressed in units of LFA labels in the equations 11 and 17, their ratio can be written as:

with \(\gamma = \frac{N_\textrm{Eu}}{N_\textrm{NV}}\). To numerically assess this ratio, we consider the parameter values listed in Table 2. The parameter \(\eta = 27~\mathrm {\%}\) is calculated from the equation of the curve shown in Fig. 5b, considering \(\tau _{\textrm{EU}} = 1~\textrm{ms}\), \(\Delta t = 400~\mathrm {\mu s}\) and \(T_0 = 200~\mathrm {\mu s}\)16,17.

The numerical value of \(\gamma\) has still to be estimated. The ND used in the experiments presented here are doped with \(\delta _\textrm{NV} = 3~\textrm{ppm}\) NV centres (1 ppm corresponds to one NV centre for \(10^6\) C atoms). The volume of one ND is \(V_{\textrm{ND}}=\frac{4}{3}.\pi .(\frac{D}{2})^3\), with D the ND diameter. Considering the crystalline structure of diamond, each cubic lattice comprises eight C atoms with a lattice side \(a = 3.57\) Å. The ration \(r = 80 \%\) of the NV centres is assumed to be in the charge state necessary for their use as fluorophores (i.e. the negatively charged state34). We therefore deduce:

Numerical values of \(N_\textrm{NV}\) for different ND diameters are shown in the Table 3.

According to the literature and following discussions with companies marketing europium-based LFA, an other important advantage of europium is the very large number of molecules that can be attached per LFA markers, i.e. per nanoparticles. The Table 3 lists examples of the number of europium molecules or NV centres per LFA markers (respectively nanoparticles or nanodiamonds) of the same size, and the resulting \(\gamma\) parameter.

The numerical value for the NEP ratio can finally be evaluated by injecting the values of the different variables, from Tables 2 and 3, into the equation (18):

Considering the assumptions detailed previously in this section, which are based on literature and discussions with suppliers of europium-based LFA, we therefore obtain an optical measurement equal to \(10^3\) more sensitive with NV centres than with europium molecules. Considering only the photophysical aspects of LFA labels, and with these assumptions, NV centres could provide detection limits similar to \(10^3\) times better than those obtained with LFA based on europium molecules, already used as quantitative LFA test.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vindolet, B., Sallem, F., Perré, A. et al. Sensitive and quantitative biosensing technique based on NV centres-doped nanodiamonds applied to lateral flow assays. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37454-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37454-6