Abstract

Toluidine Blue O is a cationic dye that can irritate human tissues and may accumulate in vital organs after repeated exposure, and its discharge into water bodies reduces light penetration and threatens aquatic life. In this work, B2O3/FeB2O4/AlBO3/Fe3BO6/C and B2O3/Al4B2O9/FeB2O4/Fe2.964O4/C nanohybrids named AFB500 and AFB700 were synthesized by a facile Pechini sol–gel route at 500 and 700 °C, respectively. The synthesized nanohybrids were applied for Toluidine Blue O removal from wastewater. XRD confirmed multiphase borate and iron oxide structures, and the average crystallite size increased from 66.69 nm for AFB500 to 81.74 nm for AFB700 due to stronger thermal treatment. EDX analysis revealed B, C, O, Al, and Fe in both nanohybrids, with higher carbon and lower Al and Fe in AFB500 and more inorganic enrichment in AFB700. FE-SEM showed plate-like and sheet-like aggregates for AFB500 and more compact granular particles for AFB700. HR-TEM images revealed mainly spherical nanoparticles for AFB500 and rod-like and plate-like crystallites for AFB700. Under optimized conditions (pH 10 and 298 K), AFB500 and AFB700 achieved Toluidine Blue O removal efficiencies of 91.62 and 64.16%, respectively. Langmuir analysis shows maximum capacities of 423.73 mg/g for AFB500 and 302.11 mg/g for AFB700. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies showed pseudo-first-order behavior and physical exothermic and spontaneous adsorption. The nanohybrids were effectively regenerated with hydrochloric acid and maintained high performance over several cycles, and they also removed Toluidine Blue O efficiently from real laboratory wastewater, which highlights their practical potential for dye-polluted effluents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colored effluents from textile dyeing, leather processing, paper manufacturing, and many other industries are a major source of water contamination because large volumes of dye solutions are discharged with limited treatment1,2. Also, many dyes are designed to resist fading during use, so they also persist in natural waters. These organic dyes absorb visible light and reduce water transparency, and they can form toxic degradation products that enter food chains and accumulate in organisms3,4,5,6,7.

Organic dyes pose serious risks to ecosystems and to human health. Many aromatic dye molecules are resistant to biodegradation and can remain in rivers and groundwater for long periods, and exposure to them has been linked to irritation of skin and eyes and to disorders of the liver and kidneys and, in some cases, to mutagenic or carcinogenic effects8,9,10,11,12.

Toluidine Blue O is a cationic thiazine dye used as a biological stain, and some diagnostic procedures and accidental releases or improper disposal result in its presence in laboratory and industrial wastewaters. Contact with Toluidine Blue O can cause irritation of skin, eyes, and mucous membranes, and ingestion or prolonged exposure may damage internal organs, while its strong color and photoreactive nature make it harmful to aquatic plants and animals13. Regarding discharge regulations, dye effluent standards are typically expressed in terms of bulk water-quality parameters (e.g., true color, COD/BOD, and aquatic toxicity) rather than dye-specific concentration limits; consequently, a universal permissible limit for Toluidine Blue O itself is generally unspecified. Reported dyehouse effluent regulations and guidelines vary by country and commonly emphasize color control and overall contaminant load as the primary compliance targets. Therefore, removing Toluidine Blue O to very low residual levels is essential to meet color/toxicity-oriented discharge requirements. In addition, Toluidine Blue O was selected as a representative cationic thiazine dye because it is strongly colored and persistent enough to cause visible contamination even at low concentrations, making it a practical model pollutant for evaluating high-capacity adsorbents. Its cationic nature also allows clear assessment of electrostatic and surface-complexation interactions on oxide/borate-based ceramic adsorbents.

Many treatment technologies have been developed to remove organic dyes from water. Conventional approaches include coagulation/flocculation14,15, membrane filtration16,17, electrodialysis18, photocatalytic degradation19,20,21, and bioremediation with bacteria or fungi22,23,24. These methods can be effective, but they often require complex infrastructure, high energy input, or strict operating conditions, and they may generate secondary wastes. Adsorption offers a simpler route because it can operate at ambient temperature and pressure and does not require sophisticated equipment. The adsorbent can often be regenerated and reused, and adsorption can reach high removal efficiencies even at relatively low dye concentrations and in the presence of other dissolved species25,26,27.

Nanotechnology deals with materials and devices that have at least one dimension in the nanometer range, and nanoparticles are central to this field28,29. Metal oxide nanoparticles and metal borate nanoparticles have attracted wide attention as adsorbents because they possess high surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and rich defect structures that provide abundant active sites for dye binding30,31. Composites that combine metal oxides or metal borates with carbonaceous phases, organic polymers, or other inorganic phases can further improve adsorption performance by enhancing stability, dispersion, and surface functionality32,33,34,35,36,37,38. In particular, mixed metal borates and mixed metal oxide borate composites can offer multiple binding environments that interact with dye molecules through electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding, and surface complexation39,40,41,42,43.

Among the many synthesis routes available, the Pechini sol–gel method is especially attractive for the preparation of metal oxide- and metal borate-based nanomaterials36,37,44,45. This method uses a chelating agent and a polymeric network to distribute metal cations uniformly at the molecular level, and after thermal treatment, it yields highly homogeneous powders with controlled stoichiometry. The Pechini route usually requires relatively mild processing conditions and allows easy adjustment of composition by changing the metal salt ratios and the organic precursors, and it is well suited for producing complex multi-component nanohybrids that would be difficult to obtain by conventional solid-state reactions46,47,48.

Several adsorbents have been reported for the removal of Toluidine Blue O from aqueous solutions, yet their performance still leaves room for improvement. Turkish zeolite shows a maximum capacity of about 42 mg/g49, and carboxymethylcellulose magnetic composite reaches 83.70 mg/g13, while gypsum exhibits only 28 mg/g50. Activated carbon/cellulose beads display a capacity of 123.5 mg/g51, NiFe2O4/carbon nanotube composite reaches 120 mg/g52, and magnetic Fe3O4/polydopamine composite gives about 123.50 mg/g53. These systems often suffer from moderate capacities or slow kinetics or difficult regeneration and, in some cases, from high costs of raw materials and synthesis steps, and therefore new adsorbents with higher capacity, faster uptake, and good stability are still required.

The present work introduces two novel nanohybrids, namely B2O3/FeB2O4/AlBO3/Fe3BO6/C and B2O3/Al4B2O9/FeB2O4/Fe2.964O4/C, prepared through a facile Pechini sol–gel route at 500 and 700 °C and denoted AFB500 and AFB700, respectively. In these materials, several borate and iron oxide phases coexist within a single carbon-containing framework, and this multiphase architecture provides a synergistic effect because different crystallographic phases contribute complementary active sites for efficient adsorption of Toluidine Blue O. The expected outcome was the development of high-capacity, fast-acting, and reusable nanohybrids capable of maintaining strong Toluidine Blue O removal even in complex wastewater matrices.

The ceramic framework composed of metal borates and iron oxides offers stable surfaces bearing –OH groups and Lewis acid/base sites, enabling strong interaction with Toluidine Blue O through electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and complexation at surface oxygen/metal centers. Meanwhile, the embedded carbon introduces conjugated domains that interact with the aromatic dye via π–π stacking, and it promotes better dispersion of the ceramic phases and faster mass transport. As a result, the combined borate/oxide–carbon architecture provides complementary binding mechanisms that increase both adsorption kinetics and capacity for cationic dye. Therefore, the main scientific novelty is the Pechini-enabled construction of a temperature-tunable, multiphase ceramic–carbon nanohybrid architecture that provides complementary binding mechanisms, and a synergistic adsorption response compared to previously reported borate-only or iron-oxide-only systems54,55.

In addition to adsorption performance, the scalability and economic feasibility of the proposed nanohybrids were considered in their design. The Pechini sol–gel route employs inexpensive and widely available inorganic salts (iron and aluminum nitrates and boric acid) together with low-cost organic complexing agents (tartaric acid and polyethylene glycol) and does not require high-pressure equipment or sophisticated processing. The synthesis is carried out in aqueous media and uses conventional drying and calcination steps that are compatible with batch or continuous industrial ceramic production. Therefore, the fabrication of AFB500 and AFB700 is inherently scalable and suitable for large-scale preparation.

Beyond its technical performance, the present work directly supports the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG-6), which aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of clean water and sanitation for all56,57,58,59. The efficient removal of hazardous dyes such as Toluidine Blue O from wastewater contributes to improving water quality, reducing aquatic toxicity, and enabling the safe reuse or discharge of treated effluents. The high adsorption capacity, regeneration ability, and effectiveness of AFB500 and AFB700 in real wastewater matrices demonstrate their potential as sustainable materials for practical water purification systems, which is in line with the targets of SDG-6 for pollution reduction, wastewater treatment, and protection of aquatic ecosystems.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tartaric acid (C4H6O6, 99%), aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3.9H2O, 98%), iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3.9H2O, 98%), boric acid (H3BO3, 99.5%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37 wt% aqueous solution), potassium chloride (KCl, 99%), polyethylene glycol 400 (H(OCH2CH2)nOH, 99%), and Toluidine Blue O dye (C15H16ClN3S, 98%), whose IUPAC name is 3-amino-7-(dimethylamino)-2-methylphenothiazin-5-ium chloride, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification. All reagents were of analytical grade, and all aqueous solutions were prepared using distilled water.

Synthesis of B2O3/FeB2O4/AlBO3/Fe3BO6/C and B2O3/Al4B2O9/FeB2O4/Fe2.964O4/C nanohybrids

The nanohybrids were obtained by a Pechini sol–gel route as outlined in Fig. 1. 21 g of tartaric acid were dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water. In a separate vessel, 12 g of Al(NO3)3.9H2O, 12 g of Fe(NO3)3.9H2O, and 12 g of boric acid were dissolved in 125 mL of distilled water. Then, the tartaric acid solution was added to the previous solution, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. Polyethylene glycol 400 with a volume of 10 mL was introduced, and the system was heated at 200 °C until complete evaporation produced a dry resin. The resulting precursor was gently ground and calcined in a programmable muffle furnace (Nabertherm LHT 08/18, Germany) for 3 h at 500 °C to yield the B2O3/FeB2O4/AlBO3/Fe3BO6/C nanohybrid labeled AFB500 and at 700 °C to obtain the B2O3/Al4B2O9/FeB2O4/Fe2.964O4/C nanohybrid labeled AFB700.

Polyethylene glycol 400 was added as a polyhydroxy polymeric agent within the Pechini route to promote the formation of a homogeneous organic network and to improve molecular-level mixing of the metal–borate precursors. During heating, polyethylene glycol 400 participates in the polymeric matrix formation and increases the viscosity of the sol, which suppresses premature segregation and favors a more uniform distribution of cations before calcination. Upon thermal treatment, the organic network decomposes, leaving residual carbonaceous domains and/or porosity that help disperse the ceramic phases and provide additional adsorption domains in the final ceramic–carbon nanohybrid42,60.

The selection of 500 and 700 °C as calcination temperatures was guided by the typical thermal evolution of Pechini-derived, borate-containing polymeric gels. As commonly reported in the literature for Pechini sol–gel precursors, dehydration and decomposition of the organic network occur at lower temperatures, and the solid obtained below ~ 500 °C is usually predominantly amorphous due to incomplete crystallization of the inorganic matrix. In contrast, the onset of crystallization and the development of well-defined borate/oxide crystalline phases generally occur at temperatures around 500 °C and above. Accordingly, calcination at 500 °C was employed as the minimum temperature to obtain crystalline phases while retaining a carbon-containing porous framework, whereas 700 °C was used to promote further crystallization and phase evolution61,62. Temperatures higher than 700 °C were deliberately avoided because, as widely documented for borate-rich compositions, excessive thermal treatment can induce softening/vitrification and glass formation, which may reduce porosity and block accessible adsorption sites63.

Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using an X-ray diffraction diffractometer (D8 Discover Bruker USA) to identify the crystalline phases of the synthesized samples. Surface morphology as well as elemental composition were examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (FE-SEM/EDX, Quanta 250 FEG, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The nanoscale structure was investigated using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM, JEM 2100Plus, JEOL Ltd, Japan). The concentration of Toluidine Blue O dye in aqueous solutions was measured with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Cintra 3030 GBC, Australia). The surface textures of AFB500 and AFB700 samples were measured at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 surface area and porosity analyzer. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy of AFB500 nanohybrid before and after adsorption of dye was performed using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 spectrometer.

Uptake of Toluidine Blue O dye pollutant from aqueous media

Batch adsorption tests were carried out in the dark to evaluate the removal of Toluidine Blue O dye from aqueous solutions using the prepared nanohybrids under the operating conditions described in Table 1, with all dye dispersions kept under constant magnetic stirring. At the end of each run, the nanohybrid was separated from the solution by centrifugation, and the residual dye concentration in the supernatant was measured at 630 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. All batch adsorption experiments were performed in duplicate, and the reported values represent the mean of duplicate runs. Error bars were added to the corresponding plots to demonstrate data reproducibility.

The dye removal efficiency, denoted as % R, was calculated according to Eq. (1), and the adsorption capacity, denoted as Q in mg/g, of the nanohybrid was determined using Eq. (2)64,65,66,67.

In these expressions, Co and Ce denote the initial and equilibrium dye concentrations in mg/L, respectively. V is the volume of the solution in liters, and W is the mass of the adsorbent in grams.

Regeneration of the Toluidine Blue O-loaded adsorbent was carried out by treating the spent nanohybrid with 100 mL of hydrochloric acid solutions at concentrations of 1, 1.5, and 2 M for 60 min, after which the solid phase was separated and the dye concentration in the recovered solution was measured spectrophotometrically. The desorption percentage of Toluidine Blue O, denoted as % D, was then evaluated using Eq. (3)68,69.

In this expression, Cd represents the dye concentration in the desorption solution in mg/L, and Vd corresponds to the volume of the desorption solution in liters.

The reusability of the synthesized nanohybrids was evaluated through five consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles in which 0.1 g of adsorbent was contacted with 150 mL of Toluidine Blue O solution at an initial concentration of 300 mg/L at 298 K as well as pH 10 for 60 min for AFB500 and 80 min for AFB700 under continuous stirring. Then, the dye-loaded solid was separated, regenerated with 100 mL of 2 M hydrochloric acid, rinsed with distilled water, dried at 60 °C, reused under the same conditions, and after each cycle the remaining Toluidine Blue O concentration was determined to monitor the retention of adsorption performance.

Binary adsorption tests were performed to investigate how coexisting ions influence the uptake of Toluidine Blue O onto AFB500 and AFB700 nanohybrids. All tests were implemented at pH 10 as well as 298 K with a preliminary Toluidine Blue O concentration of 300 mg/L, keeping the molar ratio of Toluidine Blue O to each competing ion equal to 1:1. The competing species comprised K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, NO3−, Cl−, humic acid, crystal violet, and methylene blue, which are typical cationic and anionic components present in aqueous systems. Batch adsorption tests were carried out by introducing 0.1 g of each adsorbent into 150 mL of Toluidine Blue O solution comprising the respective coexisting ion. The suspensions were agitated for 60 min concerning AFB500 as well as 80 min concerning AFB700 to ensure equilibrium conditions. After contact, the residual Toluidine Blue O concentration was estimated employing a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, then the uptake capabilities were calculated from mass balance considerations.

Evaluation of the pHPZC of the constructed adsorbent materials

The point of zero charge (pHPZC) of AFB500 and AFB700 nanohybrids was determined using a batch method in which 0.1 g of nanohybrid was introduced into 50 mL of 0.01 M KCl solution whose initial pH, denoted as pHI, had been adjusted with dilute HCl or NaOH. The suspensions were stirred at room temperature for 24 h to ensure equilibrium, and the final pH, denoted as pHF, was measured for each system. The pH change, denoted as ΔpH, was calculated according to Eq. 4, and pHPZC for each nanocomposite was taken from the plot of ΔpH versus pHI as the pH at which ΔpH equals zero70,71.

The pH values (pHI and pHF) were measured using a calibrated digital pH meter equipped with a combined glass electrode. Prior to measurements, the pH meter was calibrated using standard buffer solutions (pH 4.00, 7.00, and 10.00) at room temperature, and the electrode was rinsed with distilled water between readings.

Results and discussion

Characterization results

XRD

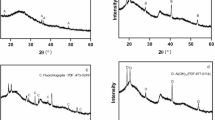

The XRD pattern of the AFB500 nanohybrid in Fig. 2A reveals the presence of B2O3 (numerical label 1), FeB2O4 (numerical label 2), AlBO3 (numerical label 3), and Fe3BO6 (numerical label 4). Boron trioxide (B2O3) corresponds to card JCPDS-00–013-0570, whose crystal system is not specified, and this phase exhibits diffraction peaks at 2θ = 14.75°, 27.99°, 30.48°, and 43.19°. The monoclinic iron(II) metaborate phase (FeB2O4), assigned to card JCPDS-01–078-9021, shows characteristic reflections at 2θ = 31.32°, 33.93°, 44.29°, 50.23°, 52.15°, 57.82°, 60.98°, 61.68°, 63.33°, 64.43°, and 66.23° with the corresponding Miller indices (020), (310), (-1 1 2), (112), (420), (330), (600), (421), (312), (511), and (040), respectively. The rhombohedral aluminum borate (AlBO3), identified by card JCPDS-00–026-007, displays peaks at 2θ = 34.91°, 39.05°, 40.29°, and 48.98° with indices (104), (006), (110), and (202), respectively. The orthorhombic iron(III) borate (Fe3BO6), matched to card JCPDS-00–018-0636, gives reflections at 2θ = 23.99°, 35.60°, 42.07°, 54.23°, 56.15°, 59.06°, and 68.45° with indices (111), (400), (231), (521), (412), (332), and (260), respectively. For the AFB700 nanohybrid, Fig. 2B confirms the coexistence of B2O3 (numerical label 1), Al4B2O9 (numerical label 2), FeB2O4 (numerical label 3), and Fe2.964O4 (numerical label 4). Boron trioxide (B2O3) again indexed to card JCPDS-00–013-0570 with an unspecified crystal system and showing peaks at 2θ = 14.61°, 27.99°, and 30.62°. Orthorhombic aluminum borate (Al4B2O9), corresponding to card JCPDS-00–029-0010, exhibits reflections at 2θ = 16.83°, 18.06°, 24.42°, 26.77°, 33.66°, and 37.66° with Miller indices (220), (111), (311), (231), (341), and (312), respectively. Monoclinic iron(II) metaborate (FeB2O4) referenced by card JCPDS-01–077-4307, whose diffraction peaks appear at 2θ = 21.93°, 36.70°, 39.17°, 40.15°, 42.07°, 43.46°, 45.95°, 48.70°, 49.80°, 56.02°, 57.82°, 59.47°, 60.72°, 66.78°, 67.75°, 69.41°, 70.65°, 72.30°, 75.06°, and 76.99° with the associated Miller indices (002), (113), (− 1 3 1), (131), (032), (− 1 3 2), (-2 2 3), (− 3 2 2), (024), (− 2 4 1), (323), (− 1 2 5), (242), (510), (− 3 3 4), (− 3 2 5), (− 5 2 1), (334), (441), and (530), respectively. Cubic iron oxide phase (Fe2.964O4), assigned to card JCPDS-01–087-0244, shows characteristic reflections at 2θ = 35.46°, 62.23°, and 65.27° with Miller indices (311), (440), and (531), respectively. The average crystallite size, which was determined using Debye–Scherrer equation72, increases from 66.69 nm for AFB500 to 81.74 nm for AFB700, which can be attributed to the higher treatment temperature used for AFB700 that enhances crystallite growth and promotes coarsening of the borate and iron oxide phases.

Hence, the change in crystalline phase assemblage between 500 and 700 °C reflects the thermally driven evolution of the Pechini-derived ceramic framework. At 500 °C (AFB500), the system is dominated by mixed metal borates (AlBO3 and Fe3BO6) together with FeB2O4 and B2O3, which are characteristic of an incompletely crystallized, borate-rich network. Upon increasing the calcination temperature to 700 °C (AFB700), these metastable borate phases undergo phase transformation and reorganization, leading to the formation of more thermodynamically stable aluminum borate (Al4B2O9) and iron oxide (Fe2.964O4), while FeB2O4 and B2O3 remain as persistent borate phases. This evolution indicates that higher thermal treatment promotes partial decomposition of complex iron borates into iron oxide and drives condensation of aluminum borates into higher-order Al4B2O9, thereby shifting the relative phase composition from borate-rich toward more oxide-enriched and highly crystalline ceramic domains.

The semi-quantitative XRD phase analysis summarized in Table 2 clearly reveals a pronounced temperature-dependent evolution of the crystalline phase assemblage. At 500 °C (AFB500), the structure is dominated by borate phases, with B2O3 (33 wt%), Fe3BO6 (25 wt%), FeB2O4 (24 wt%), and AlBO3 (18 wt%), indicating a borate-rich ceramic framework. Upon increasing the calcination temperature to 700 °C (AFB700), significant phase transformation occurs, as AlBO3 and Fe3BO6 convert into the thermodynamically more stable Al4B2O9 (27 wt%) and spinel-type iron oxide Fe2.964O4 (6 wt%), while FeB2O4 remains a persistent phase (22 wt%). The concurrent increase of B2O3 to 45 wt% reflects enhanced borate condensation and phase reorganization at higher temperature. This temperature-driven phase evolution confirms that the Pechini sol–gel route enables controlled tuning of the multiphase ceramic architecture, which directly influences the surface chemistry and adsorption performance of the nanohybrids.

EDX

Figure 3 together with Table 3 shows that both AFB500 (Fig. 3A) and AFB700 (Fig. 3B) contain B, C, O, Al, and Fe, which agrees with the formation of mixed borate and iron oxide phases. The signal of C in both samples originates from residual organic species from tartaric acid and polyethylene glycol 400 used in the Pechini sol–gel method, and this residue is more pronounced at the lower calcination temperature of AFB500. At 700 °C, the organic network is more completely decomposed, which reduces the C content and promotes crystallization and growth of Al- and Fe-rich borate and oxide domains. As a result, the relative atomic fractions of B, Al, and Fe differ between AFB500 and AFB700, while the overall oxygen level remains essentially comparable.

Although EDX confirms the presence of carbon in both AFB500 and AFB700, no distinct diffraction peaks attributable to carbon are observed in the XRD patterns. This is because the carbon generated from tartaric acid and polyethylene glycol during the Pechini sol–gel process is predominantly amorphous or poorly ordered, lacking the long-range crystallinity required to produce sharp XRD reflections. Amorphous carbon typically gives only a very broad and weak halo, which is often masked by the intense diffraction peaks of the crystalline borate and iron oxide phases. Therefore, the absence of carbon peaks in XRD is fully consistent with its disordered nature, while its presence is reliably confirmed by EDX analysis.

Increasing the calcination temperature in Pechini-derived systems can modify the apparent elemental (and thus molar) ratios of the resulting nanohybrids through two coupled effects: (i) temperature-dependent removal of the organic precursor and (ii) temperature-driven phase maturation and surface compositional evolution. At lower calcination temperature (e.g., 500 °C), a larger fraction of the polymeric network (originating from tartaric acid and polyethylene glycol 400) remains as residual carbonaceous matter, which contributes to a higher detected C content and effectively “dilutes” the relative fraction of the inorganic elements in surface-sensitive analyses. Upon calcination at higher temperature (e.g., 700 °C), the organic residue is more completely decomposed/oxidized, leading to a pronounced decrease in carbon content; because EDX data are reported as normalized atomic percentages, this decrease in C inherently increases the relative fractions of the remaining inorganic elements (B, Al, and Fe), even when the initial reagent stoichiometry is unchanged. In parallel, higher thermal treatment enhances diffusion-controlled crystallization, grain growth, and densification, which can redistribute borate/oxide domains and alter the surface composition probed by EDX, producing measurable differences in the detected B:Al:Fe ratios between samples calcined at different temperatures. Consequently, the temperature dependence of the measured “molar ratio” primarily reflects carbon burn-off, phase development, and surface compositional changes rather than a loss of boron from the system61,62.

The elemental distribution within the AFB500 nanohybrid, as an illustrative example, was further examined by EDS mapping analysis, and Fig. 4 presents the corresponding elemental maps. The obtained maps demonstrate a uniform and homogeneous dispersion of oxygen (O), carbon (C), iron (Fe), aluminum (Al), and boron (B) across the analyzed region, confirming the successful formation of the targeted nanohybrid structure. The absence of noticeable elemental agglomeration suggests an effective integration and interaction among the different components during the synthesis process. Such homogeneous distribution is essential for ensuring consistent physicochemical properties and reliable performance of the material in subsequent applications. Therefore, the mapping results provide strong evidence for the compositional uniformity and structural integrity of the AFB500 nanohybrid.

FE-SEM

Figure 5A shows the FE-SEM image of the AFB500 nanohybrid and reveals large plate-like and sheet-like agglomerates with stacked flake-like particles that form an open layered texture. Figure 5B presents the FE-SEM image of the AFB700 nanohybrid and displays more compact aggregates composed of smaller irregular block-like and nearly equiaxed grains that cover the surface uniformly. These morphologies indicate that AFB500 retains a lamellar structure inherited from the polymeric Pechini gel, whereas AFB700 is dominated by granular particles produced by more advanced crystallization and densification at higher calcination temperature. The transition from plate-like sheets in AFB500 to granular agglomerates in AFB700 is attributed to the stronger thermal treatment at 700 °C, which enhances grain growth, promotes sintering, and induces the formation of new borate and iron oxide phases with more isotropic crystal habits. As a result, AFB700 nanohybrid shows a more compact morphology and a higher degree of crystallinity than AFB500, as indicated by the finer equiaxed grains and the reduced stacking of lamellar particles in Fig. 5B.

HR-TEM

Figure 6A shows the HR-TEM image of the AFB500 nanohybrid in which the material consists of loosely packed, nearly spherical, and irregularly shaped nanoparticles that form open branched agglomerates with relatively low contrast, suggesting small crystallite domains. Figure 6B displays the HR-TEM image of the AFB700 nanohybrid, where the morphology changes to elongated rod-like and bar-like nanocrystals together with some plate-like particles that are more densely packed and exhibit higher contrast, consistent with larger and more ordered crystallites. This evolution from predominantly spherical nanoparticles in AFB500 to rod-like and plate-like crystallites in AFB700 indicates that increasing the calcination temperature during the Pechini sol–gel process enhances crystallization and promotes anisotropic growth along preferred crystallographic directions, while simultaneous sintering and coalescence of the primary particles lead to the formation of larger and more compact aggregates.

Surface textures

Figure 7 and Table 4 reveal clear differences in the textural properties of AFB500 and AFB700 nanohybrids. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (Fig. 7A) display a typical type-IV profile with a sharp increase at high relative pressures, confirming the predominance of mesoporous structures. Compared with AFB500, AFB700 shows a much steeper uptake at P/Po ≈ 1, indicating the development of larger pores. This is consistent with the BJH pore size distribution (Fig. 7B), where AFB500 is dominated by small mesopores (~ 18–35 nm), while AFB700 exhibits broader pores centered around ~ 60–100 nm. As summarized in Table 4, increasing the carbonization temperature from 500 to 700 °C decreases the BET surface area but increases the total pore volume and the mean pore diameter.

These textural changes imply that calcination at 700 °C reduces the number of accessible surface adsorption sites per gram (lower BET surface area), mainly due to sintering/coalescence and partial collapse or merging of smaller mesopores into wider voids. Although AFB700 develops a larger mean pore diameter and higher pore volume, the enlargement of pores does not necessarily increase the density of active surface functional sites (e.g., surface –OH/oxygenated groups and defect-related sites) available for dye binding; instead, it can decrease the total interfacial area in contact with solution. Consequently, AFB500 provides a higher population of accessible adsorption sites and shorter diffusion pathways within finer mesopores, whereas AFB700 presents fewer surface sites despite having larger pores, which rationalizes the lower uptake performance of AFB700 under identical operating conditions.

Optimization

Impact of pH variation on removal performance

Figure 8 shows that Toluidine Blue O removal by both nanohybrids is very low at pH 2 and much higher at pH 10. At pH 2, the uptake of the dye by AFB500 and AFB700 is almost negligible, which reflects weak interaction between the positively charged adsorbent surface and the cationic dye. At pH 10, AFB500 removes most of the dye (91.62%), while AFB700 still shows a lower yet significant removal (64.16%), which indicates a stronger affinity of AFB500 under alkaline conditions.

Adsorption mechanism

Figure 9 reveals pHPZC values of 6.79 for AFB500 and 7.22 for AFB700, so at pH 2 the surface of each nanohybrid is positively charged, and Fig. 10 illustrates that electrostatic repulsion then dominates and limits adsorption. At pH 10, the solution pH is higher than pHPZC for both materials, and the surface becomes negatively charged, so electrostatic attraction toward the cationic Toluidine Blue O prevails as shown in Fig. 10. Hence, this effect is stronger for AFB500, which explains its higher removal efficiency compared with AFB700 at this pH.

In addition to electrostatic attraction at pH > pHPZC, Toluidine Blue O uptake is supported by complementary interactions provided by the multiphase ceramic/carbon framework. Surface hydroxyl/oxygenated groups on borate and iron-oxide domains can participate in hydrogen bonding with the dye heteroatoms and may also contribute to surface complexation with the cationic chromophore. Meanwhile, the embedded carbon phase provides domains that can interact with the phenothiazine ring of Toluidine Blue O via π–π stacking, further stabilizing adsorption. Therefore, the overall mechanism involves electrostatic attraction as the primary driving force under alkaline conditions, assisted by hydrogen bonding, complexation, and π–π interactions.

Figure 11 confirms the successful adsorption of Toluidine Blue O onto AFB500, as an illustrative example, through clear changes in the EDX atomic percentages. Before adsorption, AFB500 is composed of B (7.5%), C (9.8%), O (65.4%), Al (7.0%), and Fe (10.3%). After adsorption, the surface composition shifts to B (6.0%), C (13.6%), O (68.0%), Al (3.5%), Fe (7.1%), with the appearance of S (1.5%) and N (0.3%), which are diagnostic elements of the Toluidine Blue O structure. The increase in C and O indicates the accumulation of dye-related organic/oxygenated species on the surface, while the decrease in Al and Fe suggests partial masking/coverage of the inorganic active sites by the adsorbed dye layer. The emergence of S and N provides direct elemental evidence that Toluidine Blue O molecules are anchored on AFB500 after the adsorption.

A comparison between Figs. 12 and 5A clearly reveals the morphological impact of Toluidine Blue O adsorption on the AFB500 surface as an illustrative example. Figure 5A shows that the pristine nanohybrid is characterized by well-defined plate-like and sheet-like agglomerates with an open layered texture and clearly visible surface features. After adsorption, Fig. 12 displays a noticeably different appearance in which these sharp structural details become partially obscured by a thin irregular coating attributed to the deposited dye molecules. The post-adsorption surface appears smoother, less porous, and more compact than that observed in Fig. 5A, indicating that Toluidine Blue O occupies external sites and fills accessible surface cavities. In addition, slight particle agglomeration can be observed in Fig. 12, likely resulting from intermolecular interactions between adsorbed dye species, a feature absent in the pristine morphology of Fig. 5A. These visual differences between the two figures strongly corroborate the adsorption process and are fully consistent with the elemental modifications detected by EDX analysis.

Figure 13 demonstrates in detail the molecular changes that occur on the AFB500 surface, as an illustrative example, after adsorption of Toluidine Blue O and confirms that the dye is anchored without destroying the inorganic borate framework. In the spectrum before adsorption, the bands at 550 and 640 cm−1 correspond to Fe–O and Al–O lattice stretching vibrations of the iron and aluminum borate domains, while the signals at 709 and 888 cm−1 arise from B–O–B bending and stretching modes within the borate network, indicating the integrity of the ceramic skeleton. The intense band at 1193 cm−1 is assigned to B–O stretching in BO4 units, and the peak at 1413 cm−1 represents the asymmetric B–O stretching of BO3 groups in the trigonal borate environment. The broad absorption at 3200 cm−1 reflects O–H stretching of surface hydroxyl groups and adsorbed water, which are potential active sites for dye binding. After adsorption, these structural bands remain present with slight shifts to 544, 633, and 882 cm−1, showing that the framework is preserved but its local environment is modified by surface interaction. The 1413 cm−1 band shifts to 1440 cm−1, which indicates direct involvement of BO3 oxygen atoms in coordination with the dye and alteration of the borate bonding environment. New features appear exclusively in the post-adsorption spectrum, including 447 cm−1 attributed to O–Fe–O lattice deformation, 1344 cm−1 assigned to C–N stretching of the dye amine group, 1393 cm−1 related to –CH3 symmetric deformation of the dimethylamino substituent, and 1593 cm−1 corresponding to aromatic C = C stretching of the Toluidine Blue O ring system. Moreover, the band at 2103 cm−1 is interpreted as a charge-transfer/C = N+ related vibration of the protonated thiazinium chromophore, generated through strong electronic interaction between the cationic dye and surface oxygen sites42,43,73. The coexistence of unchanged borate vibrations with these newly formed organic bands clearly proves that adsorption occurs via surface complexation and electrostatic interaction rather than structural decomposition of AFB500.

Influence of time variation on adsorption performance

Figure 14 indicates that Toluidine Blue O removal rises quickly at the beginning and then levels off as equilibrium is reached. After 10 min, AFB500 removes 43.36% of the dye, while AFB700 removes 25.27%, which shows that AFB500 adsorbs the dye more rapidly in the initial stage. For AFB500, the removal continues to increase until 60 min, where it reaches 91.45% and remains almost unchanged at longer times, confirming that the surface is saturated, and equilibrium is established. For AFB700, the adsorption is slower and less efficient, and the removal reaches 64.04% at 80 min and then becomes nearly constant, which indicates that this time is sufficient to attain equilibrium.

Figure 15A–B shows the kinetic plots for Toluidine Blue O adsorption on AFB500 and AFB700 fitted with the pseudo first order model given in Eq. (5) and the pseudo second order model given in Eq. (6)74,75,76. The extracted kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 5.

In these equations, Qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, and Qt is the adsorption capacity at time t. K1 is the rate constant of the pseudo first-order model, and K2 is the rate constant of the pseudo second-order model.

Analysis of Fig. 15 together with the kinetic parameters in Table 5 indicates that Toluidine Blue O adsorption on AFB500 and AFB700 is better described by the pseudo-first-order model. The Qe values obtained from this model are very close to the experimental capacity (QExp) and the associated R2 values reach 0.9999, which is higher than those obtained from the pseudo second-order model.

In Table 5, the “ ± ” values represent the standard errors of Qe, K1, and K2, calculated by propagating the regression uncertainties of the intercept and slope from the linearized kinetic plots. The much smaller ± values for the pseudo-first-order parameters indicate higher precision in their estimation, while the larger ± values in the pseudo-second-order model (especially for Qe) reflect greater uncertainty from that linear fitting.

Root-mean-square error (RMSE) and the chi-square test (χ2) were used to evaluate the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second order models using Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively77,78.

As shown in Table 6, the pseudo-first-order model provides a much better fit for both AFB500 and AFB700, giving very low RMSE (≈1.4) and χ2 (≤ 0.0067) values. In contrast, the pseudo-second-order model shows substantially higher errors (RMSE = 79.48–117.56 and χ2 = 17.18–26.12), indicating poorer agreement between experimental and calculated adsorption capacities.

The intra-particle diffusion model was described by Eq. (9) 79.

where, KId is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant, and C reflects the boundary-layer thickness.

The Elovich model was described by Eq. (10) 79.

where, α is the initial adsorption rate and β is the desorption/coverage parameter.

As summarized in Table 7 and illustrated in Fig. 16A–B, AFB500 shows higher KId and C values than AFB700, suggesting faster intra-particle diffusion and a stronger boundary-layer contribution for AFB500. The Elovich parameters also indicate a higher initial adsorption rate (α) for AFB500, while AFB700 exhibits a larger β, and the high R2 values (≥ 0.983) confirm that the Elovich model describes both datasets very well.

Also, the external diffusion (film diffusion) kinetic model for the elimination of Toluidine Blue O dye utilizing AFB500 and AFB700 nanoproducts was studied using Eq. (11). The external diffusion model describes the rate-limiting step as the transfer of adsorbate molecules from the bulk solution through a boundary layer (film) to the surface of the adsorbent.

Kext (1/min) is external diffusion constant whereas F is fraction attainment of equilibrium or extent of conversion, and it was calculated using Eq. (12).

Also, the pore diffusion kinetic model for the elimination of Toluidine Blue O dye utilizing AFB500 and AFB700 nanoproducts was studied using Eq. (13). The pore diffusion kinetic model describes the adsorption process controlled by the diffusion of adsorbate molecules into the internal pores of the adsorbent, where the rate of adsorption depends on both time and pore structure.

where, R is the adsorption ratio and can be calculated using Eq. (14), Ko is the initial adsorption rate constant, m is the adsorbent mass, V is the solution volume, γ is the time exponent indicating the diffusion mechanism, and t is the contact time.

As presented in Table 8 and illustrated in Fig. 17A, the external diffusion plots exhibit excellent linearity with very high coefficients for both samples, confirming that external mass transfer contributes strongly to the overall uptake. The higher Kext value for AFB500 compared with AFB700 indicates a faster boundary-layer diffusion step for AFB500. In contrast, the pore diffusion model in Fig. 17B shows slightly lower but still good fitting for AFB500 and AFB700, with comparable γ values, while AFB700 displays a larger Ko than AFB500, suggesting a relatively stronger pore-diffusion contribution for AFB700 under the studied conditions.

Influence of temperature variation on adsorption performance

Figure 18 shows that Toluidine Blue O removal decreases as the temperature increases for both adsorbents. At 298 K, AFB500 removes 91.45% of the dye, while AFB700 removes 64.04%, so AFB500 is more efficient at this temperature. At 328 K, the removal drops to 85.72% for AFB500 and 57.45% for AFB700, which indicates that higher temperature reduces the affinity of both nanohybrids for the dye and points to an exothermic adsorption process.

Figure 19 and the thermodynamic data in Table 9 indicate that Toluidine Blue O adsorption on AFB500 and AFB700 was analyzed using the Van’t Hoff approach and the associated thermodynamic relations, and the relevant parameters were calculated from Eqs. (15), (16) and (17) 80,81.

In these equations, △S° is the standard entropy change, △H° is the standard enthalpy change, R is the universal gas constant, △G° is the standard Gibbs free energy change, Kd is the distribution coefficient, and T is the absolute temperature in kelvin.

Table 9 shows that ΔH° values are negative and lower than 40 kJ/mol and that ΔG° values are also negative while ΔS° values are positive. These trends indicate that Toluidine Blue O adsorption on AFB500 and AFB700 proceeds via a physical mechanism and that the process is exothermic, spontaneous, and thermodynamically favorable.

The positive values of ΔS° observed for both AFB500 and AFB700, despite the exothermic nature of adsorption (negative ΔH°), can be attributed to an increase in interfacial disorder during Toluidine Blue O uptake. When the cationic dye molecules adsorb onto the borate/iron-oxide/carbon surfaces, structured water molecules that previously hydrated both the dye and the surface functional groups (–OH and oxygenated sites) are released into the bulk solution. This desolvation process increases the degrees of freedom of water molecules, leading to a net gain in entropy. In addition, partial surface restructuring and redistribution of surface-bound species during adsorption may further contribute to the positive entropy change. Therefore, the positive ΔS° reflects an overall increase in randomness at the solid–liquid interface, even though the adsorption itself is energetically favorable and exothermic.

Influence of amount of adsorbent variation on adsorption performance

As shown in Fig. 20, the removal efficiency of Toluidine Blue O strongly depends on the adsorbent dose. At a low dose of 0.025 g, AFB500 and AFB700 achieved removal efficiencies of 46.91 and 17.19%, respectively, indicating limited availability of active adsorption sites. Increasing the adsorbent amount to 0.10 g markedly enhanced the dye removal to 91.45% for AFB500 and 64.04% for AFB700, reflecting improved utilization of surface functional groups and adsorption domains. A further increase in the dose to 0.40 g resulted in slightly lower efficiencies of 83.19 and 57.35% for AFB500 and AFB700, respectively, which can be attributed to particle aggregation and partial overlap of active sites at higher solid loadings.

Influence of concentration variation on adsorption performance

Figure 21 shows that Toluidine Blue O removal decreases as the initial dye concentration increases for both nanohybrids. At 100 mg/L, AFB500 removes 98.15% of the dye, and AFB700 removes 93.21%, so both adsorbents are highly effective at low concentrations. At 400 mg/L, the removal drops to 68.92% for AFB500 and 48.82% for AFB700, which reflects partial saturation of the available sites at high dye loading. Over this range, AFB500 always achieves higher removal than AFB700, although both materials follow the same trend of lower percentage removal at higher initial dye concentration.

Equilibrium adsorption of Toluidine Blue O on AFB500 and AFB700 was evaluated using the Langmuir isotherm presented in Eq. (18). The same data were also interpreted with the Freundlich model as expressed in Eq. (19)82,83,84.

In these equations, Qmax is the maximum monolayer capacity, Qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity, K3 is the Langmuir affinity constant, n is the Freundlich heterogeneity factor, and K4 is the Freundlich constant.

The linear plots in Fig. 22A and B, together with the isotherm constants in Table 10, indicate that the Langmuir model fits the equilibrium data better than the Freundlich model. The higher R2 values obtained from the Langmuir plots show that Toluidine Blue O adsorption on both nanohybrids follows Langmuir-type behavior.

In Table 10, the “ ± ” values denote the standard errors of the isotherm constants, obtained by propagating the regression uncertainties of the fitted slope and intercept into Qmax, K3, 1/n, and K4. Thus, smaller ± values reflect more precise parameter estimation from the linear plots, while larger ± values indicate greater uncertainty in the fitted constants.

Root-mean-square error (RMSE) and the chi-square test (χ2) were used to evaluate the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms using Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively. Also, the model-predicted capacity (Qe,cal) from Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were calculated using Eqs. (20) and (21), respectively77.

As presented in Table 11, the Langmuir isotherm fits the experimental data better than the Freundlich model for both AFB500 and AFB700, as confirmed by the lower RMSE and χ2 values. This improvement is particularly clear for AFB700, indicating that monolayer adsorption on a more homogeneous surface is more consistent with the observed equilibrium behavior.

To further assess the favorability of the adsorption process, the dimensionless Langmuir separation factor (RL) was calculated using Eq. (22) 85.

As shown in Fig. 23, the Langmuir separation factor (RL) for both AFB500 and AFB700 remains between 0 and 1 across the studied Co range, confirming that the adsorption process is favorable. Moreover, RL decreases as Co increases and is consistently lower for AFB500 than AFB700, indicating stronger Langmuir affinity for AFB500 at all initial dye concentrations.

Table 12 summarizes the maximum adsorption capacities (Qmax) for Toluidine Blue O on different adsorbents in mg/g. Most conventional materials, such as zeolite, gypsum, chitosan hydrogel, and calcium oxide, show relatively low Qmax values, while modified or magnetic composites reach higher capacities, up to about 362 mg/g. In this work AFB500 and AFB700 display Qmax values of 423.73 and 302.11 mg/g, respectively, which are higher than those of the other reported adsorbents in Table 12. This improvement is attributed to a synergistic effect between the multiple phases present in each nanohybrid, which provides more active sites and stronger overall interaction with Toluidine Blue O.

The synthesized materials are multiphase ceramic/carbon nanohybrids produced by the Pechini method, where borate and iron-oxide phases are generated simultaneously and remain integrated within the carbon matrix. Despite several trials, phase-pure single components could not be obtained under the same synthesis route; hence, separate adsorption experiments for individual constituents were not performed. Although a rigorous quantitative ‘synergy factor’ (based on single-phase or binary controls) cannot be calculated within the present study, the synergistic role of the multiphase ceramic/carbon architecture can be supported indirectly by quantitative performance metrics. In particular, AFB500 and AFB700 exhibit high Langmuir capacities (423.73 and 302.11 mg/g, respectively) that exceed the majority of previously reported Toluidine Blue O adsorbents summarized in Table 12. Moreover, the Langmuir separation factor (RL) remains within 0–1 for both materials and is consistently lower for AFB500 than AFB700 over the investigated concentration range, indicating stronger adsorption affinity associated with the multiphase framework. These quantitative comparisons, together with the complementary interaction domains contributed by borate/oxide surfaces (electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and complexation) and carbon domains (π–π interaction and improved mass transfer), collectively support the proposed synergistic effect42,85.

In addition, the Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) isotherm model was also applied using Eq. (23) to further understand the adsorption mechanism42,86.

KDR is a constant related to the mean free energy of adsorption (mol2/kJ2), and ε is the Polanyi potential calculated using Eq. (24)42,86.

The mean free energy (E) of adsorption is estimated by Eq. (25) 42,86.

Also, Temkin isotherm was also applied using Eq. (26) to further understand the adsorption mechanism42,86.

where, B represents Temkin constant related to the heat of adsorption whereas KT (L/g) represents Temkin constant related to equilibrium bonding.

As summarized in Table 13 and illustrated in Fig. 24A–B, the D–R model shows weak fitting (low R2) compared with the Temkin model, which exhibits moderate agreement for both samples (R2≈0.81–0.83). The “ ± ” values represent the standard errors propagated from the linear regression of the D–R and Temkin plots, so larger uncertainties (notably in KT and some D–R parameters) indicate less precise parameter estimation. Additionally, the mean adsorption energy E (≈ 9.39–11.10 kJ/mol) suggests adsorption behavior stronger than simple physisorption for both AFB500 and AFB700.

Regeneration/reuse studies

Figure 25 shows that Toluidine Blue O desorption increases as the concentration of hydrochloric acid rises for both nanohybrids. At 1 M HCl, the desorption is 88.58% for AFB500 and 86.21% for AFB700. When the acid concentration is raised to 1.5 M, the desorbed fractions reach 97.27 and 93.86% for AFB500 and AFB700, respectively. At 2 M HCl, almost complete dye release is achieved with values of 99.86% for AFB500 and 99.17% for AFB700. This high efficiency is attributed to strong protonation of surface sites by HCl, which weakens the electrostatic attraction between the cationic dye and the adsorbent and allows Toluidine Blue O molecules to be displaced into the solution.

Figure 26 shows that both AFB500 and AFB700 retain good removal efficiency for Toluidine Blue O over repeated cycles, but their performance decreases slightly with each reuse. In the fresh state, AFB500 removes 91.45% of the dye, while AFB700 removes 64.04%, and after five adsorption–desorption cycles, the removal remains 86.44% for AFB500 and 55.12% for AFB700. This gradual loss is most likely due to partial blocking or loss of active sites during regeneration, but the relatively high efficiencies after several cycles indicate that both nanohybrids and especially AFB500 possess promising stability and recyclability.

To further verify the structural stability of the regenerated nanohybrids, XRD patterns were recorded after the regeneration cycle (after the fifth cycle), and no noticeable peak shift, phase disappearance, or formation of new crystalline phases was observed compared with the fresh samples, confirming that the crystalline ceramic framework remains essentially unchanged (Figures omitted for brevity). In addition, the filtrates collected after each regeneration step were analyzed by ICP, and no detectable leaching of B, Fe, or Al ions was observed, indicating excellent chemical stability of the borate/iron oxide phases under the applied acidic regeneration conditions.

Effect of interference

The influence of common coexisting ions on Toluidine Blue O uptake by AFB500 and AFB700 nanohybrids was evaluated in binary systems, and the results are listed in Table 14. In the control experiment without any competing species, AFB500 and AFB700 show capacities of 423.73 and 302.11 mg/g, respectively, and these values were taken as the reference. The presence of Na+ and K+ causes only slight losses in capacity for both adsorbents, which indicates that monovalent cations exert weak competition with Toluidine Blue O at pH 10. Mg2+ and Ca2+ lead to a more noticeable decrease in Q for AFB500 and AFB700, which suggests that divalent cations interact more strongly with the negatively charged surface sites. Cl− and NO3− have only small effects on the removal performance, and this behavior shows that these anions do not significantly hinder the adsorption of the cationic dye. In contrast, methylene blue and crystal violet cause a marked drop in Toluidine Blue O uptake for both nanohybrids, which confirms strong competition between cationic dyes for the same active sites. Under all conditions, AFB500 retains higher adsorption capacity than AFB700, which reflects its larger number of effective sites and stronger affinity toward Toluidine Blue O even in the presence of interfering species.

Effect of ionic strength

Figure 27 clearly illustrates the influence of ionic strength on the adsorption performance of AFB500 and AFB700 toward Toluidine Blue O dye. As the NaCl concentration increases, a noticeable decline in the removal efficiency is observed for both nanohybrids, indicating that the presence of electrolyte adversely affects the adsorption process. This behavior can be attributed to the shielding of electrostatic attractions between the negatively charged functional groups on the nanohybrids and the cationic dye molecules, as well as the competitive interaction of Na+ ions with active adsorption sites. Despite this reduction, AFB500 consistently exhibits higher removal efficiency than AFB700 across the investigated ionic strength range, suggesting a greater density of accessible functional groups and stronger electrostatic interactions. These results demonstrate that although ionic strength influences dye uptake, both materials, particularly AFB500, maintain appreciable adsorption capability under saline conditions, highlighting their potential applicability in real wastewater systems.

Evaluation of Toluidine Blue O sequestration from wastewater

To further evaluate the practical utility of the synthesized nanohybrids, separation experiments were carried out utilizing a real effluent wastewater sample taken from the students’ chemistry laboratories at the College of Science, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Before use, this wastewater was spiked with Toluidine Blue O to adjust its initial dye concentration to 300 mg/L so that it matched the conditions employed in the synthetic single-solute experiments while preserving the original ionic composition of the real matrix. Chemical analysis of the spiked wastewater showed the presence of several common inorganic ions originating from routine student experiments, including Na+ (58.4 mg/L), K+ (12.7 mg/L), Mg2+ (7.9 mg/L), Ca2+ (24.3 mg/L), Cl− (71.5 mg/L), NO3− (21.6 mg/L), SO42− (46.2 mg/L), HCO3− (118.0 mg/L), and PO43− (4.6 mg/L), together with low levels of trace metals such as Fe (0.23 mg/L), Cu (0.06 mg/L), and Zn (0.11 mg/L), whereas no additional organic dyes other than the intentionally added Toluidine Blue O were detected within the analytical limits. Under the previously optimized operating conditions, the adsorption capacity of AFB500 toward Toluidine Blue O in this real wastewater matrix reached 380.46 mg/g, whereas AFB700 exhibited an adsorption capacity of 268.92 mg/g, which are slightly lower than the corresponding values obtained in distilled water at the same initial dye concentration (423.73 mg/g concerning AFB500 as well as 302.11 mg/g concerning AFB700). This decrease can be attributed to competitive adsorption between Toluidine Blue O and the background inorganic ions, as well as possible partial blocking of active sites by dissolved components present in the real effluent; nevertheless, both nanohybrids maintained high removal performance, and AFB500 consistently outperformed AFB700, confirming that the material with the higher specific surface area as well as more developed porous structure retains superior adsorption efficiency even in a complex real-wastewater environment and demonstrating the suitability of these nanocomposites for treating student laboratory effluents contaminated with Toluidine Blue O.

Conclusions

The study shows that B2O3/FeB2O4/AlBO3/Fe3BO6/C and B2O3/Al4B2O9/FeB2O4/Fe2.964O4/C nanohybrids can be prepared easily by the Pechini sol–gel method and used as adsorbents for Toluidine Blue O dye. Structural and microscopic analyses confirm multiphase borate and iron oxide frameworks with carbon and reveal that AFB500 has finer particles, while AFB700 is more crystalline and compact. AFB500 and AFB700 display high maximum adsorption capacities, and their uptake of Toluidine Blue O follows the pseudo-first-order kinetic model and fits the Langmuir isotherm. Thermodynamic evaluation indicates that the adsorption process is physical, exothermic, and spontaneous over the studied temperature range. Both nanohybrids can be regenerated efficiently and maintain strong performance in real wastewater, which highlights their promise for practical treatment of Toluidine Blue O-contaminated effluents. From a practical and economic perspective, the developed nanohybrids are attractive because they are synthesized from low-cost raw materials using a simple Pechini sol–gel route and standard thermal processing, without the need for expensive templates, surfactants, or high-pressure reactors. Moreover, the high regeneration efficiency and stability over repeated adsorption–desorption cycles significantly reduce the operational cost per unit of treated water. These factors, combined with the high adsorption capacity and good performance in real wastewater, indicate that the proposed multiphase borate/iron-oxide/carbon nanohybrids are not only effective but also technically and economically viable for scalable wastewater treatment applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the article.

References

Emmanuel, S. S. et al. A Critical Review of Low-Cost Biosorbents Derived from Animal Dung for Effective Adsorption of Dye Pollutants. Clean. Water 5, 100191 (2025).

Ahmed, E. Geopolymer composite for water decontamination, United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12274996B1 (2025).

Usama, M. et al. Eco-friendly magnetic activated carbon modified with green tea extract for efficient adsorption of thiazine and azo dye contaminants from water. RSC Adv. 15, 46553–46569 (2025).

El Meziani, S. et al. Sustainable adsorption technologies for textile dye removal: Advances in biomass-derived and magnetically modified activated carbons. Clean. Chem. Eng. 12, 100210 (2025).

Ding, Y., Ji, L., Liu, Y. & Cui, Y. Preparation of copper acetate/chitosan gel material and its adsorption performance and mechanism analysis for methyl orange dye wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 324, 101510 (2025).

Bristow, R. M. D., Bossmann, S. H., Foot, P. J. S., Beadham, I. G. & Perera, A. S. Adsorption-based removal of organic dyes via a sustainably produced few-layered graphene: A potential method for industrial wastewater treatment. FlatChem 53, 100923 (2025).

Al-Kadhi, N. S., Abdelrahman, E. A., Alamro, F. S., Saad, F. A. & Al-Raimi, D. S. Innovative nanocomposite comprising of ZrO2, MnCO3, and CdCO3 for superior crystal violet dye adsorption: synthesis, characterization, and regeneration insights. Sci. Rep. 15, 5525 (2025).

Aboelnga, M. M., Seliem, M. M., El-Bayoumy, E. & El-Tahawy, M. DFT investigation of dye adsorption on pristine and doped graphdiyne: toward efficient removal of disperse yellow 3 from wastewater. Nanoscale Adv. 7, 7363–7381 (2025).

Bhargava, M. & Agarwal, J. Recyclable triptycene-based oligomers for selective cationic dye adsorption. React. Funct. Polym. 217, 106467 (2025).

Waisi, B. I., Al-Musawy, WKh., Ahmed, S. B. & Al-Furaiji, M. H. Design of porous activated carbon beads: Controlling size and structure for optimal dye adsorption. Desalination Water Treat. 324, 101533 (2025).

Brahma, D. & Saikia, H. Surfactants assisted synthesis of CuAl-sodium dodecyl sulfate layered double hydroxide and its adsorptive removal of methyl red dye from aqueous solution. Inorganic Nano-Metal Chem. 53, 605–620 (2023).

Brahma, D., Nath, K. P., Patgiri, M. & Saikia, H. Synthesis of ternary CaNiAl-layered double hydroxide as potential adsorbent for Congo red dye removal in aqueous solution. Asian J. Chem. 34, 3215–3223 (2022).

Brandão, W. Q. et al. Carboxymethylcellulose magnetic composite for adsorptive removal of cationic toluidine blue dye. Mater. Chem. Phys. 303, 127782 (2023).

Iloamaeke, I. M., Atune, S. I., Onyeije, U. C. & Onuegbu, T. U. Optimization of coagulation-flocculation process for colour removal in purification of paint industry effluent using novel seed of Spondias mombin Linn. Desalination Water Treat. 323, 101284 (2025).

Chebbi, M. et al. Single and combined treatment processes for rhodamine B removal by coagulation–flocculation and adsorption. RSC Adv. 14, 37833–37845 (2024).

Kouzi, Y. et al. Tailored rGO-TiO2-pPD low-cost ceramic membrane for dye wastewater filtration: A synergistic strategy of GO reduction, intercalation and crosslinking. Sep. Purif. Technol. 378, 134643 (2025).

Lima, A. M. et al. Filtration membranes of reduced graphene oxide for dye removal – production and characterization. Desalination Water Treat. 278, 217–225 (2022).

Leng, Q. et al. Electrochemical removal of synthetic methyl orange dyeing wastewater by reverse electrodialysis reactor: Experiment and mineralizing model. Environ. Res. 214, 114064 (2022).

Shishir, Md. K. H. et al. Photocatalytic removal of textile dyes: Analytical strategies for post-degradation evaluation. Desalination 617, 119437 (2026).

Selvi, M., Balasubramaniyan, S. & Jagatheesan, R. Sphere-like Nb2O5 nanoparticles by waste Brassica oleracea leaf extract for lead removal and photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 101, 101377 (2024).

Zheng, X., Sun, J., Yang, M. & Li, Z. Facile construction of HOF@ZnO/TiO2 ternary composite for efficient photocatalytic degradation of dyes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 718, 164829 (2026).

Periyasamy, A. P. A review of bioremediation of textile dye containing wastewater. Cleaner Water 4, 100092 (2025).

Rajamanickam, R. & Selvasembian, R. Biotransformation pathway, growth inhibition, and biochemical response of Scenedesmus obliquus to brilliant green dye: Implications for bioremediation. Biochem. Eng. J. 225, 109927 (2026).

Mburu, A. W. et al. Bioremediation of reactive black 5 textile dye wastewater using bacterial exopolysaccharides. Res. J. Text. Appar. 29, 536–549 (2025).

Das, N. et al. Dye removal from wastewater using ferrihydrite-modified sugarcane bagasse and biochar: Adsorption performance and modeling analysis. Environmental Challenges 22, 101390 (2026).

Wang, Y. et al. Defective MOFs doped with cerium (III) for enhanced phosphate removal and dye adsorption. J. Water Process Eng. 78, 108766 (2025).

Rahmanivahid, B., Nayebzadeh, H., Meybodi, F. S. & Salehi, R. Optimized synthesis and adsorption efficiency of magnetic spinel CuFe2O4 for dye removal from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 222, 57–72 (2025).

Ahmed, E. PbTiO3/TiO2/Zn2Ti3O8 nanocomposite material and method of preparation thereof. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12357979B1 (2025).

Ahmed, E. Synthesis of cobalt oxide nanoparticles using L-valine as a fuel. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12325643B1 (2025).

Ahmad, M. et al. DFT and comparative adsorption study of NiO, MnO, and Mn2NiO4 nanomaterials for the removal of amaranth dye from synthetic water. RSC Adv. 14, 28285–28297 (2024).

Wu, R., Qu, J., He, H. & Yu, Y. Removal of azo-dye Acid Red B (ARB) by adsorption and catalytic combustion using magnetic CuFe2O4 powder. Appl. Catal. B 48, 49–56 (2004).

Hashemian, S., Rahimi, M. & Kerdegari, A. A. CuFe2O4@graphene nanocomposite as a sorbent for removal of alizarine yellow azo dye from aqueous solutions. Desalination Water Treat. 57, 14696–14707 (2016).

Katowah, D. F. & Al-zahrani, H. K. A new ternary nanocomposites-based cellulose derivatives-CuFe2O4-zeolite with ultra-high adsorption capacity for Brilliant Green dye treatment and removal from the aquatic environment. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27, 101764 (2023).

Barooah, P., Mushahary, N., Das, B. & Basumatary, S. Waste biomass-based graphene oxide decorated with ternary metal oxide (MnO-NiO-ZnO) composite for adsorption of methylene blue dye. Cleaner Water 2, 100049 (2024).

Ahmed, E. Method of producing a mesoporous chitosan/NaFeSi2O6 based nanocomposite. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12330137B1 (2025).

Ahmed, E. Nanocomposite for the immobilization or degradation of pollutants. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12453951B1 (2025).

Ahmed, E. & Abdulkhair, B. Nanocomposite for wastewater treatment. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12459834B1 (2025).

Ahmed, E. A.-K. M. A. A. Nanocomposite for the immobilization or degradation of pollutants. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12453952B1 (2025).

Rubab, R., Ali, S., Rehman, A. U., Khan, S. A. & Khan, A. M. Templated synthesis of NiO/SiO2 nanocomposite for dye removal applications: Adsorption kinetics and thermodynamic properties. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 615, 126253 (2021).

Wang, M., Jiao, Y., Li, N. & Su, Y. Synthesis of a SiO2-MgO composite material derived from yellow phosphorus slag with excellent malachite green adsorption activity. J. Alloys Compd. 969, 172344 (2023).

Saini, J., Garg, V. K. & Gupta, R. K. Removal of Methylene Blue from aqueous solution by Fe3O4@Ag/SiO2 nanospheres: Synthesis, characterization and adsorption performance. J. Mol. Liq. 250, 413–422 (2018).

Abdelrahman, E. A. Efficient adsorption of basic fuchsin dye using thermally engineered novel smart nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 15, 26232 (2025).

Abdelrahman, E. A. Simple Fabrication of SrCrO4/MgO-Derived Hybrid Nanocomposites for Effective Crystal Violet Dye Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 35, 8963–8975 (2025).

Ahmed, E. Mesoporous nanocomposite. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12281048B1 (2025).

Ahmed, E. Method of forming zinc oxide/borate nanocomposite. United States Patent and Trademark Office, US12275651B1 (2025).

Jamdar, M. et al. Synthesis of SmMnO3/Sm2O3 nanocomposites as efficient photocatalysts for organic dye degradation by sol gel pechini method. Res. Eng. 21, 101650 (2024).

Ranjeh, M., Beshkar, F., Amiri, O., Salavati-Niasari, M. & Moayedi, H. Pechini sol-gel synthesis of Cu2O/Li3BO3 and CuO/Li3BO3 nanocomposites for visible light-driven photocatalytic degradation of dye pollutant. J. Alloys Compd. 815, 152451 (2020).

Del Toro, R., Hernández, P., Díaz, Y. & Brito, J. L. Synthesis of La0.8Sr0.2FeO3 perovskites nanocrystals by Pechini sol–gel method. Mater. Lett. 107, 231–234 (2013).

Alpat, S. K., Özbayrak, Ö., Alpat, Ş & Akçay, H. The adsorption kinetics and removal of cationic dye, Toluidine Blue O, from aqueous solution with Turkish zeolite. J. Hazard. Mater. 151, 213–220 (2008).

Rauf, M. A., Qadri, S. M., Ashraf, S. & Al-Mansoori, K. M. Adsorption studies of Toluidine Blue from aqueous solutions onto gypsum. Chem. Eng. J. 150, 90–95 (2009).

Harada, N., Nakamura, J. & Uyama, H. Single-step fabrication and environmental applications of activated carbon-containing porous cellulose beads. React. Funct. Polym. 160, 104830 (2021).

Bahgat, M., Farghali, A. A., El Rouby, W. M. A. & Khedr, M. H. Efficiency, Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Toluidine Blue Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution Using MWCNTs Decorated with NiFe2O4. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 22, 454–470 (2014).

Zolgharnein, J., Feshki, S., Rastgordani, M. & Ravansalar, S. Simultaneous removal of Basic blue and Toluidine blue O dyes by Magnetic Fe3O4@polydopamine nanoparticle as an efficient adsorbent using derivative spectrophotometric determination and central composite design optimization. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 146, 110203 (2022).

Şentürk, İ & Pekgözlü, İ. Preparation, characterization and adsorption properties of Ba2Mg(BO3)2 adsorbent for anionic dye Acid Violet 17. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 102, 102231 (2025).

Divya, V., Anbarasu, K., Vickram, A. S. & Saravanan, A. Iron-Based Nanohybrids for Sustainable Dye Removal from Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review on Adsorption Mechanisms and Environmental Implications. Hybrid Advances 12, 100607 (2026).

Mukherjee, A., Mahanty, E. & Dhak, D. Chemisorption of Emerging Contaminants (F−, AsIII/V, Pb2+) Using MOF for Sustainable Water Treatment: A Critical Review. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 35, 6147–6175 (2025).

Mukherjee, A. & Dhak, D. Biorefinery waste-based nanocomposites for industrial effluents treatment using physicochemical techniques. Biorefinery of Industrial Effluents for a Sustainable Circular Economy 235–2025, 235–254 (2025).

Mukherjee, A., Dhak, P., Mandal, D. & Dhak, D. Solvothermal synthesis of 3D rod-shaped Ti/Al/Cr nano-oxide for photodegradation of wastewater micropollutants under sunlight: a green way to achieve SDG:6. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 56901–56916 (2023).

Mukherjee, A., Dhak, P., Hazra, V., Goswami, N. & Dhak, D. Synthesis of mesoporous Fe/Al/La trimetallic oxide for photodegradation of various water-soluble dyes: Kinetic, mechanistic, and pH studies. Environ. Res. 217, 114862 (2023).

Ghaani, M. R., Mohtasebi, A. M., Tajeri, R. & Marashi, P. A comparison of the role of the chelating agent on the structure of lithium conducting solid electrolyte Li1.4Al0.4Ti1.6(PO4)3: Pechini vs modified pechini-type methods. Batteries 6, 48 (2020).

Al-Wasidi, A. S., El-Feky, H. H., Shah, R. K., Saad, F. A. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Simplified synthesis and identification of novel nanostructures consisting of cobalt borate and cobalt oxide for crystal violet dye removal from aquatic environments. Sci. Rep. 14, 21631 (2024).

Alghanmi, R. M. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Simple production and characterization of ZnO/MgO nanocomposite as a highly effective adsorbent for eliminating congo red dye from water-based solutions. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 161, 112137 (2024).

Aleksandrov, L., Iordanova, R. & Dimitriev, Y. Glass formation in the MoO3–Nd2O3–La2O3–B2O3 system. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 355, 2023–2026 (2009).

Alhalili, Z. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Efficient removal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous media using a facilely synthesized nanocomposite based on chitosan Schiff base. Sci. Rep. 14, 17598 (2024).

Abdelrahman, E. A., Goda, M. N., Khedr, A. M., Saad, F. A. & Shah, R. K. Thermal tuning of nanocomposites for superior cadmium ion adsorption. Sci. Rep. 15, 24003 (2025).

Verma, A., Dhiman, P., García-Peñas, A. & Sharma, G. Activated carbon/polyacrylamide-cl-xanthan gum nanocomposite for adsorption of methylene blue dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 321, 146186 (2025).

Rind, I. K., Lanjwani, M. F., Sarı, A., Tuzen, M. & Saleh, T. A. Adsorption of Sudan II dye onto fly ash/polyacrylic acid/melamine composite: Factorial design optimization, reusability performance and removal mechanism. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 39, 101283 (2024).

Abdelrahman, E. A., Shah, R. K., Abou-Krisha, M. M., Saad, F. A. & Munshi, A. M. Facile synthesis and characterization of novel Fe0.65Mg0.35Cr2O4@C nanocomposite for efficient removal of Cd(II) Ions from Aqueous Media. Inorganics (Basel) 13, 82 (2025).

Kenawy, I. M. M., Abou El-Reash, Y. G., Hassanien, M. M., Alnagar, N. R. & Mortada, W. I. Use of microwave irradiation for modification of mesoporous silica nanoparticles by thioglycolic acid for removal of cadmium and mercury. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 258, 217–227 (2018).

Hashem, Md. A. et al. Dye adsorption on fish scale biosorbent from tannery wastewater. Next Sustain. 6, 100112 (2025).

Gupta, S., Prajapati, A., Kumar, A. & Acharya, S. Synthesis of silica aerogel and its application for removal of crystal violet dye by adsorption. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 5, 241–254 (2023).

Uysal, Y. & Doğaroğlu, Z. G. Citrus Peel-Mediated ZnO Nanoparticles: Green synthesis, plant responses, and antibacterial activity. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 70, 103854 (2025).

Abdelrahman, E. A., Alhamzani, A. G., Abou-Krisha, M. M., Shah, R. K. & Alamri, H. M. Advanced multiphase nanocomposites for effective malachite green dye removal. Sci. Rep. 15, 26101 (2025).

Kishore, K. et al. Efficient removal of toxic dyes from water using Mn3O4 nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and adsorption mechanisms. J. Mol. Struct. 1333, 141756 (2025).

Hui, Y., Liu, R., Lan, J., Sun, T. & Xu, A. Recyclable chitosan adsorbent: Facile functionalization strategy, excellent removal capacity of dyes and adsorption mechanism. Chemosphere 359, 142291 (2024).

Rajesh, Y. et al. Synthesis, characterization and adsorption studies on activated carbon adsorbent synthesized from Kigelia africana for removal of acid blue 113 dye from synthetic solution. Mater. Today Proc. 111, 69–77 (2024).

Ncibi, M. C. Applicability of some statistical tools to predict optimum adsorption isotherm after linear and non-linear regression analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 153, 207–212 (2008).

Abdelrahman, E. A., Elamin, M. R., Al-Kadhi, N. S., Shah, R. K. & Alashqar, S. Engineering Novel Nanocomposites Containing Multiphase Metal Borates and Carbon for Basic Blue 41 Sequestration from Wastewater. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 11, 101103 (2026).

Al-Kadhi, N. S., Abdelrahman, E. A. & Shah, R. K. Innovative synthesis of hybrid nanocomposites based on strontium chromate for malachite green dye removal from aqueous media. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 23, 34 (2026).

Umar, A. et al. Synthesis of trimetallic; CuNiZn-BTC MOF for the removal of patent blue VF dye from aqueous solutions. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 180, 114942 (2025).

Dalmaz, A. & Özak, S. S. Methylene blue dye efficient removal using activated carbon developed from waste cigarette butts: Adsorption, thermodynamic and kinetics. Fuel 372, 132151 (2024).

Moatamed Sabzevar, A., Ahmadpour, A., Ghahramaninezhad, M. & Arami-Niya, A. Improving structural properties and adsorption performance of kraft lignin-based microspheres for anionic dye removal. Ind. Crops Prod. 234, 121640 (2025).

Praipipat, P. et al. Synthesis and characterization of metal oxide dopped beaded sugarcane bagasse fly ash for direct red 28 dye removal. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 128, 495–514 (2023).

Al-Wasidi, A. S., Abdelrahman, E. A., Shah, R. K., Abdelhakim, N. A. & Saad, F. A. Facile synthesis of novel nanocomposite composed of Co3O4, MgO, and Mg3B2O6 for malachite green dye decontamination from aqueous media. Sci. Rep. 14, 30570 (2024).

Al-Wasidi, A. S. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Efficient remediation of malachite green dye utilizing novel and straightforwardly constructed nanocomposite. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 102, 101994 (2025).

Abdelrahman, E. A., Abou El-Reash, Y. G., Youssef, H. M., Kotp, Y. H. & Hegazey, R. M. Utilization of rice husk and waste aluminum cans for the synthesis of some nanosized zeolite, zeolite/zeolite, and geopolymer/zeolite products for the efficient removal of Co(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) ions from aqueous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123813 (2021).

Das, T. & Patel, D. K. Efficient removal of cationic dyes using lemon peel-chitosan hydrogel composite: RSM-CCD optimization and adsorption studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 275, 133561 (2024).

Ofudje, E. A. et al. Eggshell derived calcium oxide nanoparticles for Toluidine blue removal. Desalination Water Treat. 247, 294–308 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2602).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2602).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions