Abstract

False or unnecessary Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) alerts risk undermining public trust, potentially leading to alert fatigue or disengagement, a critical concern for policymakers. Although false alerts are inherently unpredictable, a rare opportunity to study one arose on October 26, 2024, when a planned military explosion was mistakenly classified as a magnitude 5.2 earthquake by the Israeli EEW system, triggering alerts to over one million people. This was the first-ever public EEW alert in Israel and occurred during wartime, following a year of near-daily missile alerts. A preregistered survey (N = 1,043) was conducted shortly after this event. Because the alert was geographically limited, the incident offered a quasi-experimental opportunity to compare attitudes between those who received the alert and those who did not. Results showed that the public remained largely motivated to follow EEW guidance and had considerable tolerance for false alerts. However, tolerance was significantly lower for false EEW alerts than false missile alerts, indicating different public perceptions of seismic versus security threats. Despite the false alert and prolonged exposure to alerts, public support for receiving warning, even for non-damaging, felt events, remained strong. These findings highlight the resilience of public trust and offer insights for designing effective alert systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perceived usefulness and trust are critical for the effectiveness of public warnings about natural hazards1. If people do not trust the warning system, they may ignore instructions or even disable the alerts entirely2,3. In particular, false or unnecessary alerts can erode public trust in Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) systems4. Due to the inherent limitations of current EEW systems and high uncertainties, policymakers use a magnitude threshold above which alerts are sent, aiming to balance between urgency and necessity5. Prior research suggests that EEW alerts following an earthquake are not perceived as false alerts, and they are often interpreted as precautionary, even when no damage occurs or shaking is not felt6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. A key concern among policymakers is that a low-magnitude alert threshold could lead to frequent over-alerting. This, in turn, may cause alert fatigue or desensitization, sometimes described as the “crying wolf” effect14,15,16,17.

Despite these concerns, a survey conducted in Israel following the February 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes in Türkiye, an event widely felt across Israel but which caused no local damage and fell outside the EEW system’s operational range for issuing alerts, found that the public favored a non-conservative alert strategy (i.e., lower magnitude threshold) and reported high motivation to comply with future EEW instructions, even in cases of precautionary alerts5.

These findings suggest relatively high tolerance for false (when no earthquake occurred) or unnecessary (precautionary, non-damaging ground motions) alerts. However, studying public reactions to false alerts in real-world settings remains a significant challenge due to their unpredictability.

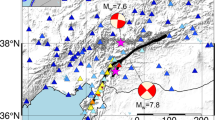

A unique opportunity to study public responses to an unnecessary EEW alert emerged on October 26, 2024. On that date, at 7:02 AM local time (4:02 AM UTC), the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) initiated a controlled detonation of approximately 370 tons of explosives (equivalent to Mw 3.6) to destroy underground military infrastructure in southern Lebanon (latitude 33.243, longitude 35.525), as part of the ongoing conflict18. The resulting seismic signal was mistakenly classified by Israel’s national EEW system, Truaa, as a magnitude 5.2 earthquake, triggering a false EEW alert across northern Israel. More than one million people received the alert via mobile apps and sirens. This event marked the first public activation of Israel’s EEW system, and it occurred amid an ongoing war and following a year of frequent missile alerts in the region.

To leverage this opportunity and examine public reactions to this unprecedented alert, we conducted a preregistered survey (N = 1,043) within days of the event. Importantly, because the alert was only issued in northern Israel, we were able to compare responses between individuals who received the alert and those who did not, creating a rare quasi-experimental setup to assess the real-world impact of a false EEW alert on public trust and compliance, and alert perceptions more broadly. This study offers an unusual opportunity to explore public perceptions of false EEW alerts, especially in a context of elevated alert frequency and high public exposure to missile threats.

Israel: A unique laboratory for alert research

Israel is located along the Dead Sea Fault, a boundary between the African and the Arabian tectonic plates (Fig. 1). The seismic hazard in the region is high despite the relatively low rate of large earthquakes, and historical records and geodynamic calculations reveal that this fault has the potential to produce an M ~ 6 and M ~ 7 earthquake every 102 and 103 years, respectively19.

Due to the seismic hazard imposed by the Dead Sea Fault, the State of Israel established an EEW system, Truaa, which became operational on January 27, 2022, and is composed of 120 seismic stations20. Data are processed in real time by the Geological Survey of Israel (GSI) using the ShakeAlert EPIC algorithm21,22, adapted for local conditions23,24,25. Once an earthquake’s magnitude, location, and origin time are estimated, alerts are disseminated by the IDF Home Front Command (HFC) according to the alert policy, through sirens, media, and a mobile app that also delivers missile attack warnings.

The alert tone for earthquakes is similar to missile alerts, followed by a verbal “Earthquake” message (in Hebrew) repeated three times after five seconds, accompanied by text and response instructions in the app. Alerts are issued when the estimated magnitude exceeds M4.5 and are disseminated to an area where peak ground acceleration is predicted to surpass 5 cm/s² (0.5%g)24.

Earthquake safety guidelines in Israel differ from the globally common “Drop, Cover, and Hold On” (DCHO) approach. Instead, the prevailing advice is to flee the building when possible. Historically, the “flee outside” instruction was introduced for schools and kindergartens, as many such facilities occupy older buildings constructed before modern seismic standards. The Home Front Command later extended this guidance to the general public, replacing earlier recommendations. In high-rise buildings, individuals are instructed to move into a fortified room (i.e., reinforced room, originally designed for missile protection, but also structurally robust during earthquakes, and a standard feature in homes and apartments since the 1990 s) or a structurally robust stairwell. DCHO is only recommended when no better alternative exists2,26.

During the first three years of Truaa’s operational stage, 32 local and regional earthquakes, with a magnitude range of Mw 2.5–7.8, were reported as felt in Israel (GSI catalog), with no reports of any damage. Note that some of these earthquakes occurred at a distance of 700 km from Israel, thus none of these earthquakes resulted in a public EEW from Truaa, except for the October 26, 2024, unnecessary EEW.

The first public EEW

On October 26, 2024, at 7:02 AM local time (04:02:39.243 UTC), a scheduled detonation of 370 tons of explosives was carried out by the IDF to destroy a 1.5-km underground Hezbollah military installation in southern Lebanon, as part of the ongoing war18,27,28. The blast, equivalent to Mw3.6 and located just 2.2 km from the nearest seismic station (IS.MSAM), produced seismic signals that Truaa initially misinterpreted29. Four seconds after origin time, the system issued a preliminary solution (i.e., the earthquake’s location, origin time, and magnitude), estimating the magnitude at M5.2 and mislocating the event by over 20 km (Fig. 1).

The magnitude and location error resulted from a combination of the algorithm’s optimization for deeper tectonic earthquakes and the proximity of an intense energy release18. Since the estimated magnitude exceeded the M4.5 threshold, HFC issued an alert across northern Israel, affecting approximately one million residents.

In Israel, although earthquake and missile alerting systems are disseminated through similar channels, they differ in frequency, immediacy, tone, and prescribed behavioral responses. Missile alerts are issued frequently, particularly during war time, with a constant lead time between 15 and 90 s before expected impact, depending on location, and instruct the public to take immediate protective action, such as entering a shelter or a fortified room. In contrast, EEW alerts are very rare, provide usually shorter lead times that depend on distance from the epicenter, and are intended to prompt precautionary actions aimed at reducing injury (e.g., fleeing buildings or moving to safer locations). The earthquake alert uses a tone similar to missile alerts sirens, followed by a verbal “Earthquake” message repeated three times after five seconds, and written instructions in the app.

This false earthquake alert occurred during a period of near-daily missile warnings, offering a rare opportunity to examine how the public responds to EEW and false, or unnecessary, alerts. The similarity in the alert tones and delivery mechanisms between EEW and missile alerts in Israel5, combined with the high frequency of missile alerts for over a year during wartime, presents a natural setting for investigating alert fatigue and public tolerance for false alerts. We set out to explore the following key research questions (hereafter, we use the term “false” for both false and unnecessary alerts):

1. Assessing the public’s alert preferences after a false alert: How does experiencing a false EEW alert affect public preferences for when alerts should be issued?

2. Tolerance for false alerts after an incident: Does experiencing a false EEW alert change how tolerant people are to false earthquake alerts, and how does this compare to false missile alerts?

3. Impact of wartime alert exposure: Does prolonged exposure to frequent missile alerts during wartime influence preferences for receiving EEW alerts?

4. Future compliance: Does experiencing a false EEW alert reduce intentions to comply with future alerts?

5. Behavioral response: What protective actions did people take during the EEW alert?

Whereas previous studies examined public perceptions of EEW systems either after true alerts6,13 or prior to system implementation8,30, this study is one of the first to assess public sentiment following a false EEW alert, and to do so in a high-alert environment due to war. We aim to inform policymakers by identifying the public’s tolerance thresholds and alert preferences, critical factors for designing an effective warning-system strategy.

Data collection began within 48 h of the false alert to maximize high recall accuracy while allowing time for public awareness that the EEW alert was false, as widely reported across media outlets [e.g. 27,31]. The study was preregistered at [https://aspredicted.org/6xxv-4ycz.pdf] and conducted in line with the university’s ethical guidelines. All participants gave informed consent. The full survey questionnaire is provided in Appendix A of the Supplementary Materials.

The false alert aftermath and geography. Location map for Truaa’s first alert (red cross) and its last location update (black cross), catalog location (circle), and seismic stations (triangles). The extent of the magnitude-dependent alert zone is marked in pink. The inset map shows the location of the main map (dashed rectangle), with local, active faults along the Dead Sea Transform (DST) marked as red, adapted from32.

The survey

The survey included several key measures designed to assess public attitudes toward earthquake alerts. These included (1) preferred alerting strategy (participants’ preferences regarding when EEW alerts should be issued), (2) tolerance for false alerts (perceived legitimacy and willingness to accept false alerts for both earthquake and missile threats), (3) impact on future compliance with EEW (intentions to follow official guidance after receiving an alert), and (4) behavioral response to the false EEW alert (actions taken during the October 26 alert, among those who received it).

To ensure coverage of both exposed and unexposed individuals, the survey was distributed to residents of northern Israel (where the alert was sent; to capture those likely to have received the alert) as well as to residents of other regions (to capture those who did not receive an alert). Participants’ geographic locations were determined based on panel-provided addresses.

To validate alert receipt, all respondents were asked, “Did you receive an earthquake alert on Saturday, October 26, 2024, at 07:02 AM?”. Response options were: “Yes”, “No”, “No, I didn’t receive an earthquake alert, but someone next to me did”, “I don’t remember”, and “Other”. All 1,043 completed responses were retained in the dataset, though as preregistered, our primary analysis compares those who answered “Yes” (N = 462; 44.3%) to those who answered “No” (N = 490; 47.0%). Responses from the remaining 91 participants (8.7%) who selected the other options are described in Appendix B of the Supplementary Materials.

Participants (N = 1043) ranged in age from 20 to 73 years (M = 46.21, SD = 14.59). Approximately half were women (48.6%), the majority were Hebrew speakers (92.2%) and Israeli-born (86.4%). Most self-identified as secular (60.5%), with 26.5% conservative and 12.8% religious, and 93.0% reported a high-school education or above. Full demographic distributions are provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

A similar survey conducted in 2023 following the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes in Türkiye5 (hereinafter: the 2023 survey) was used as a baseline comparison for some of the questions, particularly regarding alert preferences and compliance intentions.

A detailed description of the survey’s methods and measures is provided in the Section Methods and Measures.

Results

Preferred alerting strategy

We found that among all participants, a significant majority of 70.85% reported a preference for a non-conservative strategy (alerting for felt events, locally or nationally, even without any damage) for earthquake alerts (p < 0.001 on a binomial test compared to 50%). Specifically, 24.35% wanted to receive an alert for any earthquake felt in Israel, and 46.50% wanted an alert for any earthquake felt in their region (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Alert strategy preferences for the full sample. Labels correspond to reply options: No Alert - I do not wish to receive any alerts at all; Severe Damage - Every earthquake that can cause severe damage in my region; Light Damage - Every earthquake that can cause slight damage in my region; Felt Locally - Every earthquake that can be felt in my region; Felt Nationally - Every earthquake that can be felt in Israel.

Effect of receiving the alert

Preferences for earthquake alerts did not differ meaningfully between individuals who received the EEW alert and those who did not.

A chi-square test comparing the categorical distribution of alert preferences across the five response options showed no significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 1.98, p = 0.740). In both groups, the majority favored a non-conservative alerting strategy, that is, receiving alerts for felt events locally or nationally, even when no damage is expected. Specifically, 69.3% of those who received the false alert and 72.0% of those who did not, preferred a non-conservative strategy (p > 0.50; Table 1).

Demographic effects

We examined whether demographic factors (age, gender, language, religiosity, education, and country of birth) predicted preferences for alerting strategy. None of these variables showed significant associations with participants’ alert preferences (all ps > 0.05). Further details are provided in Appendix E in the Supplementary Materials.

Comparison to the 2023 sample

Preferences for issuing earthquake alerts became significantly less conservative from 2023 to the current 2024 survey (χ² = 54.67, p < 0.001). In 2023, 63.1% of participants preferred a non-conservative alert strategy (alerts for felt earthquakes, locally or nationally, even without any damage), compared to 70.9% in 2024, a significant increase (χ² = 12.97, p < 0.001; Table 1).

This change reflects a shift in distribution across categories rather than a uniform change. For example, 32.8% of respondents in 2023 preferred receiving alerts for any felt earthquake in Israel, whereas this dropped to 24.4% in 2024. At the same time, preference for receiving alerts for earthquakes felt specifically in one’s own region increased sharply (from 30.3% to 46.5%). This suggests a move toward more targeted yet proactive alerting, rather than either stricter or broader alerting policies.

Overall, these results show a significant increase in support for non-conservative alert strategies, reflecting the public’s growing preference for receiving EEW alerts even in uncertain situations, with a growing preference for receiving more alerts rather than fewer (Table 1).

Tolerance for false alerts

Participants judged false earthquake alerts to be somewhat less legitimate than false missile alerts (Mean = 5.05, SD = 1.98 vs. Mean = 5.70, SD = 1.74, respectively), t(1042) = 12.70, p < 0.001, d = 0.39 (paired sample t-test). Although both types of alerts were rated relatively high in legitimacy, missile alerts were perceived as moderately more justified overall. A similar but smaller pattern emerged for tolerance ratings, with participants being slightly less tolerant of false EEW alerts (Mean = 5.51, SD = 1.71) than of false missile alerts (Mean = 5.78, SD = 1.69), t(1042) = 6.32, p < 0.001, d = 0.20. These findings indicate a modest yet reliable difference, suggesting that missile alerts are seen as more legitimate and acceptable, even when false.

Effect of receiving the alert

To examine whether experiencing a false EEW alert changes how tolerant people are to false earthquake alerts, and how this compares to false missile alerts, we conducted two mixed-design ANOVAs: a 2 (Alert Receipt: Received vs. Not Received; between-subjects) × 2 (Alert Type: EEW vs. Missile; within-subjects) design, with perceived legitimacy and tolerance as dependent variables.

Participants who received the false EEW alert did not differ meaningfully from those who did not receive it in their ratings of legitimacy or tolerance for either alert type.

Legitimacy. There was a significant main effect of Alert Type (F(1, 950) = 157.15, p < 0.001, η² = 0.142), indicating that participants rated false missile alerts as moderately more legitimate (Mean = 5.70, SD = 1.74) than false earthquake alerts (Mean = 5.05, SD = 1.98). Neither the main effect of Alert Receipt (F(1, 950) = 0.63, p = 0.429, η² = 0.001), nor the interaction between Alert Type and Alert Receipt (F(1, 950) = 2.36, p = 0.125, η² = 0.002) was significant. Mean legitimacy ratings were nearly identical between participants who received the false EEW (EEW: Mean = 5.05, SD = 1.99; Missile: Mean = 5.79, SD = 1.59) and those who did not (EEW: Mean = 5.04, SD = 2.01; Missile: Mean = 5.63, SD = 1.85).

Tolerance. A similar but smaller pattern emerged, with higher tolerance for false missile alerts (Mean = 5.80, SD = 1.67) than for false earthquake alerts (Mean = 5.51, SD = 1.71), yielding a significant main effect of Alert Type (F(1, 950) = 43.16, p < 0.001, η² = 0.043). Neither the main effect of Alert Receipt (F(1, 950) = 0.02, p = 0.893, η² < 0.001), nor the interaction between Alert Type and Alert Receipt (F(1, 950) = 0.58, p = 0.448, η² = 0.001) was significant. Mean tolerance ratings were very similar between those who received the false EEW (EEW: Mean = 5.50, SD = 1.69; Missile: Mean = 5.83, SD = 1.61) and those who did not (EEW: Mean = 5.52, SD = 1.72; Missile: Mean = 5.78, SD = 1.72).

Together, these results suggest that receiving a false EEW alert did not reduce trust or tolerance, for either earthquake alerts or missile alerts. Although false missile alerts are viewed as somewhat more justified than false earthquake alerts, exposure to the false alert itself had no measurable effect on these perceptions.

Demographic effects

We examined whether demographic factors (age, gender, language, religiosity, education, and country of birth) predicted perceptions of alert legitimacy and tolerance. Age was the only consistent predictor, with older participants expressing greater legitimacy and tolerance toward both earthquake and missile alerts (ps < 0.001). No other demographic factors, nor their interactions with alert receipt, were significant (ps > 0.17). Further details are provided in Appendix E in the Supplementary Materials.

Comparison to the 2023 sample

The 2023 survey did not include these measures, and therefore no comparison is available.

Impact on future compliance with EEW

A large majority of participants (91.5%) reported that they would continue following public guidance in response to future EEW alerts, even if they experienced false alerts and/or non-damaging ones. Specifically, 61.9% reported that they would “definitely” follow instructions, and 29.5% would “probably” follow them. This proportion was significantly above a 50% baseline (binomial test, p < 0.001), indicating high tolerance for over-alerting. However, further research is needed to determine if this tolerance persists in reality.

Effect of receiving the alert

To robustly assess whether receiving the false EEW alert affected future compliance intentions, we conducted several complementary analyses, treating the compliance item both as a continuous variable and as a categorical outcome. Receiving the false EEW alert did not significantly impact participants’ intentions to comply with future alerts. Using the 5-point scale (1 = “definitely not”, 5 = “definitely yes”; Table 2), mean compliance ratings were statistically similar for participants who received the alert (Mean = 4.47, SD = 0.82) and those who did not (Mean = 4.54, SD = 0.07), t(950) = 1.31, p = 0.190, d = 0.09. A categorical comparison yielded consistent results, with no significant distributional difference between the groups (χ2 = 5.56, p = 0.234; chi-square test). Taken together, these results suggest that a single false alert did not undermine willingness to comply with future EEW guidance.

Demographic effects

To examine whether demographic characteristics predicted compliance intentions, we regressed compliance on age, gender, language, religiosity, education, and country of birth. Age was the only significant predictor, with older participants reporting higher intentions to comply with future EEW alerts (β = 0.13, p < 0.001), whereas no other demographic factors significantly predicted compliance (all ps > 0.15). Further details are provided in Appendix E in the Supplementary Materials.

Comparison to the 2023 sample

Though the 2023 and 2024 surveys differed slightly in wording (i.e., using a hypothetical scenario in 2023 and a real event in 2024), the response format was identical, allowing for a meaningful comparison. Compliance intentions (i.e., definitely or probably continue following guidance) increased significantly from 80.1% in 2023 to 91.5% in 2024 (χ2 = 51.29, p < 0.001, chi-square test). This shift was also evident on the continuous scale: Mean2023 = 4.05 (SD = 0.86) vs. Mean2024 = 4.50 (SD = 0.77), t(1908) = 11.97, p < 0.001, d = 0.55 (t-test).

In 2023, 31.8% of participants said they would “definitely” comply and 48.3% would “probably” comply. In 2024, the share of those saying “definitely” rose substantially to 61.9%. This suggests that recent real-life exposure to alert systems, both missile and EEW, may have reinforced public trust and compliance, rather than weakened it. Table 2 shows the distribution of future compliance intentions.

Behavioral response to the alert

Among participants who reported receiving the EEW alert (N = 462), 79.1% took some form of action, while 20.1% did not take any action. The most common protective behavior was entering a fortified room (36.4%), followed by fleeing outdoors (18.6%) and going to a staircase (2.8%). A smaller number moved away from potential hazards (1.9%), while none reported taking cover under heavy furniture, the standard response in many other countries. Some participants indicated that they were already in a safe place (7.1%) or mentally prepared without taking physical action (5.0%). A few engaged in less typical actions such as standing under a doorframe, lying on the ground, protecting others (e.g., children), or stopping their vehicle (each about 0.4%). Additionally, 6.3% provided open-text responses, further demonstrating the diversity of actions taken (e.g., “I was confused”, “I thought it was a mistake”, “I thought it was a cyber-attack”, “It woke me up in the middle of the night”, or “I waited and went back to sleep”). These findings suggest that while the intent to follow EEW guidance is high, the actual responses vary widely. They point to a need for research and clearer public education on how to respond effectively to earthquake alerts, especially in a context where multiple alert types (e.g., missile and earthquake) coexist and may create ambiguity or confusion.

Demographic effects

We next examined whether demographic characteristics predicted behavioral responses among participants who received the false alert. A binary logistic regression predicting whether participants took action versus not revealed that gender was the only significant predictor (B = 0.56, SE = 0.24, p = 0.020, Exp(B) = 1.74), indicating that women were more likely than men to act. The overall model was not significant, χ²(6) = 8.36, p = 0.213, Nagelkerke R² = 0.028, and no other demographic variables were related to action likelihood (all ps > 0.25). Further details are reported in Appendix E of the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

This study leverages a rare real-world event to examine how an unnecessary (false) Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) alert influences public perceptions of earthquake alert systems. Uniquely, because the alert was issued only in northern Israel, we were able to compare attitudes between individuals who received the alert and those who did not, creating a quasi-experimental design in a natural setting. Moreover, the study was conducted during an active wartime period marked by frequent missile alerts, allowing us to assess whether prolonged exposure to life-saving security alerts shaped public attitudes toward EEW. By comparing responses to a similar 2023 survey conducted before the war, we also explored whether preferences for earthquake alerts changed over time in the context of sustained alert saturation.

The selection of alert thresholds is a strategic decision5. Our findings suggest that Israeli decision-makers’ concern about alert fatigue, which led them to set a relatively high alert threshold for EEW, may be overstated. In both the 2023 and 2024 surveys, participants expressed strong preferences for a non-conservative alert policy, one that includes alerts for felt but non-damaging earthquakes. These preferences remained stable even after a full year of near-daily missile alerts and despite exposure to a false EEW. This implies robust public support for precautionary alerting, even under conditions of high alert saturation.

Importantly, exposure to the false EEW did not diminish trust in the system or reduce willingness to follow future alert behavioral guidelines. Participants who received the alert were just as likely as those who did not to endorse future compliance. In fact, overall intentions to comply with EEW guidance increased significantly from 2023 to 2024, with more than 91% indicating they would continue to follow instructions, even after receiving multiple non-damaging alerts. Notably, age emerged as a consistent predictor across outcomes: older participants judged false alerts as more legitimate and more tolerable, and expressed higher willingness to comply with future EEW alerts. This pattern is consistent with findings from other countries, albeit in different contexts, showing that older individuals tend to view EEW systems as more useful and reliable33. These findings offer encouraging evidence that one false alert, especially in a highly alert-exposed population, does not immediately undermine system credibility or behavioral intent.

An important and related question concerns the trade-off between rapidity and accuracy in early warning systems. While this trade-off is not examined directly in the present study, it is addressed in depth in a previous work5 to which interested readers are referred.

Behavioral responses during the false alert were also relatively encouraging. Among participants who reported receiving an alert, 79.1% took some form of protective action, well above compliance rates reported in previous studies conducted in Japan6,34 or the USA13. Gender also played a role in behavioral response: women were significantly more likely than men to take protective action during the alert, consistent with patterns reported in prior EEW and disaster-preparedness research2,35,36. This high compliance rate was likely shaped by the fact that, at the time, residents were experiencing frequent missile alerts. It may also reflect broad trust in the IDF’s well-established missile-alert system rather than specific familiarity with EEW protocols. While 71.2% of participants recognized the alert was for an earthquake, 28.8% did not, and 29.7% did not immediately distinguish the EEW signal from a missile alert. These gaps point to the need for clearer public education and alert distinction.

Despite the overall tolerance for false alerts, false EEW alerts were rated as less legitimate and less tolerable than false missile alerts. This was true for both those who received the EEW alert and those who did not. One possible explanation is that missile threats are more tangible, with visible and frequent consequences during wartime, whereas earthquakes are rarer and less salient. Another explanation is institutional trust: Israel’s military alert systems have long-standing credibility, whereas the EEW system is relatively new and still earning public confidence. Open-ended responses reinforced these themes. Participants expressed a mix of appreciation for the alert, recognition of its importance, and calls for greater public awareness and education. Some emphasized the benefit of the false alert, while others voiced confusion or stress stemming from the unfamiliar signal. For example: “How can you not be tolerant? It is obviously very stressful, but mistakes happen, and it is better to have these kinds of mistakes than not to have alerts when needed”; “This is a very important system, especially when statistics show there should be an earthquake in the next years”; “The false alert is stressful, but raises the awareness of how to react to one”; “It is very good there is such a system, I was not aware of it”; “This was a good practice”; “I wish someone would tell us that there is such a system!”; “I think it is important to teach the public the relative instructions, especially after a year of war, where people are automated to react to missile alerts, and might react incorrectly”. These comments highlight the importance of ongoing communication, transparency, and public training as the EEW system matures.

It is necessary to note that this study has its limitations. All measures in this study were self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. Participants were recruited from an online panel based on geographic location, which does not constitute a nationally representative sample. Therefore, generalizations from these findings should be made cautiously. Additionally, while our findings offer an encouraging indication of public acceptance and tolerance of EEW alerts, further longitudinal research is needed to understand how repeated exposure to false alerts or alerts for non-damaging events may affect long-term compliance and trust. High self-reported intentions to follow guidelines may not always translate into consistent real-world behavior, particularly over time or with repeated unnecessary alerts, where “alert fatigue” may become a concern. Another limitation concerns the uniqueness of the situation: while it enabled the collection of rare and valuable real-world data, the exceptional wartime context limits the generalizability of the findings and highlights the need for longitudinal research.

Taken together, this work makes several important contributions to the literature on warning systems and risk communication. First, we demonstrate that public trust and willingness to comply with EEW guidance remain resilient even after experiencing a false alert, providing a critical finding for policymakers concerned about the “cry wolf” effect. Second, we show that prolonged exposure to life-saving missile alerts does not reduce public support for precautionary earthquake warnings, addressing a gap in understanding how multiple overlapping alert systems interact in shaping public attitudes. Third, we document real-time public behavioral responses during the false alert, revealing both high rates of protective action and notable ambiguity or misinterpretation, highlighting the need for clearer education on EEW protocols. Finally, by comparing preferences and compliance intentions to data collected a year earlier, we show stability, and even increased support, for non-conservative alerting strategies despite a highly alert-saturated environment.

Overall, this study highlights the resilience of public trust in emergency alerts, even after a false alert, while also calling attention to the need for improved system communication and public education. Researchers should continue to monitor long-term trends in trust and behavior as the EEW system evolves and future alerts are issued.

Methods and measures

This section is part of the main manuscript and describes all methodological details of the survey.

As preregistered, we initially collected data from 500 participants, aiming for at least 200 respondents who reported receiving the false EEW alert and 200 who did not. We continued data collection in increments of 50 until we reached a minimum of 200 participants per condition. Given the unique opportunity presented by this event, we eventually aimed to extend our sample to 1,000 participants (analysis of the first 500 is detailed in Appendix C of the Supplementary Materials). In total, 1,068 individuals were recruited through an online panel across Israel. Of these, 25 did not complete the survey, resulting in a final sample of 1,043 respondents (mean age = 46.21; SD = 14.6; 48.6% female). The experiment was approved by the Review Board Committee of the Arison School of Business, Reichman University. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

To better understand the impact of false EEW alert on participants’ preferences and compliance, we leveraged a unique opportunity to compare these preferences to those measured in a separate survey5 (referred to as: the 2023 survey), conducted immediately after the February 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes, which were felt in the region (N = 867; mean age = 42.27, SD = 14.58; 44.4% female; 236 individuals (27.2%) reported feeling the earthquakes)5. This comparison offered two key advantages: (1) it allowed us to contrast a hypothetical scenario (e.g., “If you received several earthquake alerts and no damage”) with a real scenario (i.e., an actual EEW alert with no damage), and (2) it enabled us to compare current EEW perceptions with those before the war; during the war, hundreds of missile alerts were issued.

After providing informed consent, participants were told that the study focused on earthquake alerts. They then answered a series of questions related to their experiences, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as demographic information, including geographic location. Our goal was to assess four key domains: (1) preferred alert strategies (e.g., conservative vs. non-conservative earthquake alerting), (2) tolerance for false EEW alerts, (3) intentions to comply with future EEW alerts, and (4) behavioral responses to the alert. Because the alert was issued only in northern Israel, the sample allowed for a quasi-experimental comparison between participants who reported receiving the alert and those who did not. This distinction served as the basis for our primary analyses. Additional survey items, such as demographic questions and open-ended responses, are documented in full in the questionnaire provided in Appendix A, and analyses of these items are reported in Appendices D-E of the Supplementary Materials.

Preferred alerting strategy

To assess participants’ preferences regarding earthquake-alert thresholds, they were asked: “In case of an earthquake, when would you like an earthquake early warning system to alert you?” Participants selected from five response options, which reflected a scale from more conservative to more non-conservative alert strategies. A conservative strategy prioritizes necessity by issuing warnings only when severe damage is likely. In contrast, a non-conservative strategy prioritizes urgency and public awareness, issuing alerts even for minor or merely felt events. The response options were: “I do not wish to receive alerts at all”, “For every earthquake that might cause severe damage in my region”, “For every earthquake that can cause slight damage in my region”, “For every earthquake that can be felt in my region”, and “For every earthquake that can be felt in Israel”.

The same question and coding scheme were used in the 2023 survey, allowing for direct comparisons across years.

Tolerance of false alerts

To assess tolerance of false alerts, participants evaluated the legitimacy and their willingness to tolerate false alerts for both earthquakes (EEW) and security-threat alerts (e.g., missile, rocket, or unmanned aerial vehicle alerts). For each domain, participants responded to a legitimacy scale: “How legitimate and reasonable is it for a false alert of this type to occur?” (1 = “not legitimate and unreasonable to occur” to 7 = “legitimate and reasonable to occur”); and a tolerance scale: “To what extent are you willing to tolerate false alerts of this type?” (1 = “zero tolerance” to 7 = “full tolerance”).

Each participant thus responded to four items in total: two related to EEW alerts and two to security-threat alerts. These items were not included in the 2023 survey.

Impact on future compliance with EEW

To examine the effect of experiencing a false EEW on future compliance, participants were asked, “In light of the false earthquake warning issued on Saturday, 26.10, will you continue to follow public behavioral guidelines every time there is an earthquake warning?” Response options were “Definitely not”, “Most likely not”, “Either yes or no”, “Most likely yes”, and “Definitely yes”.

The 2023 survey included a similar item, though it was phrased as a hypothetical question given that no EEW alerts were disseminated at the time: “If you received several earthquake alerts and no damage ultimately occurred as a result of these earthquakes, would you continue to follow public guidelines every time there is an earthquake warning?” The response options were identical.

Behavioral response to the false EEW

Participants who reported receiving the alert were also asked how they reacted during the event. Response options included: “I did not react”; “I did not react – I was already in a safe place”; “I did not react, but I braced myself mentally”; “I moved away from potential hazards such as windows, unstable objects, or block walls”; “I fled the building”; “I entered a sheltered room”; “I entered a stairwell”; “I ducked under furniture”; “I stood in a door jamb”; “I ducked and took cover”; “I protected the people around me (e.g., children, special needs)”; “I stopped the car”. An open-text option was provided for other responses.

Demographics

Participants provided demographic information, including their place of residence over the past year, age, gender, mother-tongue language, country of birth, religion, and education. Upon completion of the survey, participants were debriefed, provided with the Israeli EEW instructions, and thanked for their participation.

Data availability

The dataset collected and analyzed during the current study is available in the following link: [https://osf.io/c2hwf/?view_only=95f6cb0cc7cf4152a921872c22ec9802].

References

Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C. & Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception Paradox—Implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Anal. 33, 1049–1065 (2013).

McBride, S. K. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for protective actions and earthquake early warning systems. GEOPHYSICS 87, WA77–WA102 (2022).

Tan, M. L., Vinnell, L. J., Valentin, A. P. M., Prasanna, R. & Becker, J. S. The public’s perception of an earthquake early warning system: A study on factors influencing continuance intention. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 97, 104032 (2023).

McBride, S. K. et al. Developing post-alert messaging for ShakeAlert, the earthquake early warning system for the West Coast of the united States of America. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 101713 (2020).

Nof, R. N., Yagoda-Biran, G. & Zwebner, Y. The urgency-necessity earthquake alert trade-off: considering the public response factor. Nat. Hazards. 121, 8951–8973 (2025).

Nakayachi, K., Becker, J. S., Potter, S. H. & Dixon, M. Residents’ reactions to earthquake early warnings in Japan. Risk Anal. 39, 1723–1740 (2019).

Fallou, L., Finazzi, F. & Bossu, R. Efficacy and usefulness of an independent public earthquake early warning system: A case Study—The earthquake network initiative in Peru. Seismol. Res. Lett. 93, 827–839 (2022).

Becker, J. S. et al. Earthquake early warning in Aotearoa new zealand: a survey of public perspectives to guide warning system development. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 7, 138 (2020).

Bossu, R., Finazzi, F., Steed, R., Fallou, L. & Bondár, I. Shaking in 5 Seconds!—Performance and user appreciation assessment of the earthquake network Smartphone-Based public earthquake early warning system. Seismol. Res. Lett. 93, 137–148 (2021).

Bostrom, A. et al. Great expectations for earthquake early warnings on the united States West Coast. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 82, 103296 (2022).

Dallo, I. et al. Earthquake early warning in countries where damaging earthquakes only occur every 50 to 150 years – The societal perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 83, 103441 (2022).

Allen, R., Cochran, E., Huggins, T., Miles, S. & Otegui, D. Lessons from Mexico’s Earthquake Early Warning System. Eos 99, (2018).

Goltz, J. D. et al. The Ojai California earthquake of 20 August 2023: earthquake early warning performance and alert recipient response in the Mw 5.1 event. Seismol. Res. Lett. 95, 2745–2760 (2024).

Atwood, L. E. & Major, A. M. Exploring the cry Wolf hypothesis. Int. J. Mass. Emergencies Disasters. 16, 279–302 (1998).

Reddy, E. Crying ‘Crying wolf’: how misfires and Mexican engineering expertise are made meaningful. Ethnos 85, 335–350 (2020).

Saunders, J. K., Minson, S. E. & Baltay, A. S. How low should we alert? Quantifying intensity threshold alerting strategies for earthquake early warning in the united States. Earth’s Future. 10, 1–20 (2022).

Vinnell, L. J., Tan, M. L., Prasanna, R. & Becker, J. S. Knowledge, perceptions, and behavioral responses to earthquake early warning in Aotearoa new Zealand. Front. Commun. 8, 1229247 (2023).

Schardong, L. et al. Earthquake Early Warning alert in Israel due to a 370 T explosion in southern Lebanon, October 26, Poster at CTBT Science & Technology Conference (SnT2025) (Vienna, Austria, 2025) (2024). https://conferences.ctbto.org/event/30/contributions/5650/attachments/2872/6017/P2.2-338_Schardong_lightning.pdf

Hamiel, Y. et al. The seismicity along the dead sea fault during the last 60,000 years. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 99, 2020–2026 (2009).

Kurzon, I. et al. The TRUAA seismic network: upgrading the Israel seismic Network—Toward National earthquake early warning system. Seismol. Res. Lett. 91, 3236–3255 (2020).

Given, D. D. et al. Revised technical implementation plan for the shakealert system—An earthquake early warning system for the West Coast of the united States. Open-File Rep. 54 https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181155 (2018). https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20181155

Kohler, M. D. et al. Earthquake early warning shakealert 2.0: public rollout. Seismol. Res. Lett. 91, 1763–1775 (2020).

Nof, R. N. & Allen, R. M. Implementing the ElarmS earthquake early warning algorithm on the Israeli seismic network. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 106, 2332–2344 (2016).

Nof, R. N., Lior, I. & Kurzon, I. Earthquake early warning system in Israel — Towards an operational stage. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 1–12 (2021).

Nof, R. N. & Kurzon, I. TRUAA—Earthquake early warning system for israel: implementation and current status. Seismol. Res. Lett. 92, 325–341 (2021).

Rapaport, C. & Ashkenazi, I. Drop down or flee out? New official earthquake recommended instructions for schools and kindergartens in Israel. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 10, 52–64 (2019).

Fabian, E. Footage shows IDF massive explosion which triggered earthquake alerts across Northern Israel this morning. Times Israel (2024). https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/footage-shows-massive-idf-explosion-which-triggered-earthquake-alerts-across-northern-israel-this-morning/

IDF. IDF forces located and destroyed a strategic underground Hezbollah facility: Footage. (2024). https://www.idf.il/אתרי-יחידות/יומן-המלחמה/כל-הכתבות/הפצות/כוחות-צה-ל-איתרו-והשמידו-מתקן-אסטרטגי-תת-קרקעי-של-חיזבאללה-תיעוד/?90. [Hebrew].

Geological Survey of Israel. Official announcement regarding seismic event on October 26. [Hebrew] (2024). https://www.gov.il/he/pages/news-false-alarm-eq. (2024).

Clinton, J., Zollo, A., Marmureanu, A., Zulfikar, C. & Parolai, S. State-of-the Art and future of earthquake early warning in the European region. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 14, 2441–2458 (2016).

Baaklini, S. Why large Israeli explosions in Odaisseh Raised fears of a potential earthquake. L’Orient-Le Jour (2024). https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1433133/why-large-israeli-explosions-in-odaisseh-raised-fears-of-a-potential-earthquake.html

Sharon, M., Sagy, A., Kurzon, I., Marco, S. & Rosensaft, M. Assessment of seismic sources and capable faults through hierarchic tectonic criteria: implications for seismic hazard in the levant. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 125–148 (2020).

Santos-Reyes, J. Influencing factors on the usefulness of an earthquake early warning system during the 2017 Mexico City earthquakes. Sustainability 13, 11499 (2021).

Nakayachi, K., Yokoi, R. & Goltz, J. Human behavioral response to earthquake early warnings (EEW): are alerts received on mobile phones inhibiting protective actions? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 105, 104401 (2024).

Goltz, J. D. & Bourque, L. B. Earthquakes and human behavior: A sociological perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 21, 251–265 (2017).

Santos-Reyes, J. & Gouzeva, T. Adolescents’ responses to the 2017 Puebla earthquake in Mexico City. JDR 18, 771–782 (2023).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Steering Committee for Earthquake Preparedness through GSI project number 40889.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the main manuscript text. Y.Z. and G.Y-B. prepared the survey. Y.Z. conducted the survey. R.N.N. created the figures. All authors analyzed the survey results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yagoda-Biran, G., Nof, R.N. & Zwebner, Y. Monitoring public reaction to an unnecessary earthquake early warning alert. Sci Rep 16, 4715 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37958-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37958-1