Abstract

Events of high dust loading are extreme meteorological phenomena with important climate and health implications. Therefore, early forecasting is critical for mitigating their adverse effects. Dust modeling is a long-standing challenge due to the multiscale nature of the governing meteorological dynamics and the complex coupling between atmospheric particles and the underlying atmospheric flow patterns. While physics-based numerical modeling is commonly being used, we propose a meteorological-based deep multi-task learning approach for forecasting dust events. Our approach consists of forecasting the local PM10 (primary task) measured in situ, and simultaneously to predict the satellite-based regional PM10 (auxiliary task); thus, leveraging valuable information from a correlated task. We use 18 years of regional meteorological data to train a neural forecast model for dust events in Israel. Twenty-four hours before the dust event, the model can detect 76% of the events with even higher predictability of winter and spring events. Further analysis shows that local dynamics drive most misclassified events, meaning that the coherent driving meteorology in the region holds a predictive skill. Further, we use machine-learning interpretability methods to reveal the meteorological patterns the model has learned, thus highlighting the important features that govern dust events in the Middle East, being primarily lower-tropospheric winds, and Aerosol Optical Depth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High dust events are extreme meteorological phenomena that often initiate in arid and semi-arid regions but can extend to remote areas. Studies have shown that dust events significantly impact both the physical and human environments due to the dust particles’ properties1,2. The associations between high dust loading and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases have been documented in a large body of literature3. As climate change and droughts have caused this phenomenon to endanger the lives of many people worldwide, studying dust events formation and forecasting is of ever-growing importance.

High dust events are particularly frequent in the Middle East and specifically in Israel, located at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, on the margin of the global dust belt. This region has a diverse geography and is influenced by various synoptic systems associated with dust events4,5, hence attracting substantial research interest.

Modeling and predicting high dust events is a long-standing challenge due to the multiscale nature of the governing meteorological dynamics and the complex coupling between the atmospheric particles and the underlying wind patterns. The latter necessitates numerical coupling of model dynamics and physics to other processes involving aerosol processes. There are still significant uncertainties about the underlying coupled processes governing dust emission, transport", and deposition, especially given that they occur on scales that current models do not resolve.

Detailed physics-based numerical modeling is typically used for dust forecasting6,7. These models are based on assumptions regarding the emission and transport of dust storms; these predictions are thus highly model-dependent and often suffer from low skill8. Data-driven machine-learning algorithms have become a popular alternative to theory-driven models due to their ability to handle highly complex dynamic systems without being explicitly programmed9,10. In particular, deep learning, a family of machine-learning methods that have shown phenomenal successes in computer vision, natural language processing, and other fields, is increasingly adopted in the Earth and climate sciences, achieving notable success11.

Recent studies successfully implemented machine learning in dust modeling and forecasting12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. For example, Shi et al.15 and Jiang et al.14 performed pixel-wise dust detection in typical dust regions of Asia using Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), respectively. Other studies concentrated on forecasting particulate matter with a diameter equal or smaller than 10 μm (PM10), a metric often used to define hazardous dust events13. Kang et al.16, Kowalski et al.21, and Nidzgorska-Lencewicz22 forecasted PM10 one or several hours ahead based on historical measurements from those monitoring stations where forecasting is made, using deep-learning approaches. Chae et al.12 spatially interpolated similar stationary measurements and then transferred them into a CNN for real-time spatial PM10 prediction. In the Middle East region, Shtein et al.17 spatially predicted intra-daily PM10 levels in Israel using satellite Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) and regression models; Harba et al.18 used CNN to predict the direction of a dust storm using a small set of satellite images from Iraq; Boroughani et al.20 used different machine-learning models and satellite images to identify dust sources in north-eastern Iran.

These models either detect dust using real-time data (nowcasting) or forecast dust with only a few hours of lead time from historical ground stationary measurements. None of these models use large-scale meteorological history as an input. Furthermore, in some studies, dust event definition depends on methods of questionable accuracy23. In other studies, it is difficult to generalize the results to longer spatial or temporal ranges because the training data contains only a few esoteric cases. To the best of our knowledge, a large-scale meteorology-based deep neural model for forecasting dust levels at lead times longer than 24 h has not been studied. In particular, a model that can be reliably validated using ground in situ observation.

We hypothesize that the lack of such studies mainly stems from three unique challenges that the combination of meteorology, dust, and deep-learning poses: (i) meteorological training samples are highly correlated; (ii) dust events are relatively rare; (iii) meteorological fields are not shift-invariant. More precisely, (i) and (ii) imply redundancy and the low entropy of the already scarce training samples; this appears to attenuate the performance of deep-learning models, which largely depend on the quantity and the diversity of the training data24. Moreover, (iii) invalidates common data augmentation techniques for extracting more information from small datasets. This issue is further discussed in “Discussion”.

In this study, we developed a meteorology-based deep neural model, which forecasts local dust events in Israel from 12 to 72 h in advance. We use in situ PM10 measurements for the years 2003–2020 to define high dust events. We propose a multi-task learning25 model to overcome the abovementioned challenges. This model simultaneously predicts regional PM10 levels (regional task) and PM10 levels in Israel (local task). For the regional task supervision, we use satellite-based PM10 retrievals. As discussed in “Discussion”, the multi-task framework improves local dust event forecasting by utilizing regional-scale information in the regional task’s meteorological signals. The model consists of two neural networks trained simultaneously: An autoencoder network learns to compress multivariate meteorological samples into concise codes that keep both local and regional features; a fully connected (FC) network learns to forecast local PM10 levels using sequences of these codes.

The model can skillfully detect about 76% of dust events 24 h ahead, with even higher predictability of winter and spring events. Our analysis shows that most misclassified events are driven by local dynamics. Furthermore, we reveal the spatiotemporal importance that the neural networks attribute to the meteorological variables and thus conclude the essential meteorological features that govern dust events in the region.

Results

\({\Phi}_{loc}\) and \({\Phi}_{reg}\) are deep neural networks that predict the local and the regional PM10 concentration, respectively, as detailed in “Model”.

Multi-task validation

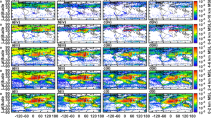

Figure 1a presents selected examples of regional PM10 original maps, and their predictions, obtained by \({\Phi}_{reg}\). The examples were sampled from the validation set. As can be seen, the decoder can reconstruct the regional PM10 fields with high precision from the encoder’s 512-length codes. Although the outputs of \({\Phi}_{reg}\) are usually smoother than the original, the fact that the leading regional dust regions are detected is well noticeable. Our analysis suggests that the accuracy of \({\Phi}_{reg}\) is relatively stable over time (not shown). In addition, we find that \({\Phi}_{reg}\)’s errors are systematically smaller in the north of the Sahara and the southwestern Arabian Peninsula in relation to other regions (Supplementary Fig. 1). A potential explanation for this is that the network focuses on predicting PM10 in the regions of the sources and the atmospheric pathways of the local PM10. This finding may indicate that the network has learned to discriminate between regions in order to improve the local prediction, thus reinforcing the efficiency of our solution.

a The code’s regional task representation: Selected examples from the validation set of original and predicted regional PM10 fields. Prediction was performed using the model’s autoencoder, \({\Phi}_{reg}\). b Code’s local task representation: Boxplots of the first PCA component of the encoder codes over eight time points in 12 h intervals. Sequences that are followed by dust events in 24 h after the last time points (orange), and those that do not (blue) are compared.

We use principal component analysis (PCA) to visually illustrate the ability of the encoder codes to capture local-scale features, in addition to the regional-scale features. The PCA was computed over all validation set’s encoder codes. Note that PCA’s first component is the direction that best explains the variability between codes. Figure 1b presents the distribution of the codes’ first principal component over eight successive time points; we compare sequences that are followed by a dust event (orange) and those that are not (blue). The first principal component can statistically discriminate between the two groups already 108 h before a dust event. These results indicate that the encoder codes preserve local-scale dust-related features. They also demonstrate the high compressibility of the model; i.e., it reduces 194,040 floating-point numbers (pixels in the 40 × 49 × 99 input tensor) to a single value with significant discriminative power.

Dust event forecasting

Figure 2 presents the recall and precision (defined in “Model”) of \({\Phi}_{loc}\) for increasing forecast lead time over the validation set. We also report these metrics for a subset of samples taken in the winter–spring months (December to April), when most of the events occur. For comparison, we report the performance of a Naive classifier, which always returns the last observed state (persistence), and a Shallow classifier (i.e., non-deep machine learning), which is a state-of-the-art gradient boosting algorithm (XGBoost) operated on the entire (flattened) input data.

Presented are the recall and precision of \({\Phi}_{loc}\) over all months of the year (solid blue and orange lines) and between December to April only (dashed blue and orange lines); the precision–recall average of a Shallow classifier composed of an extreme gradient boosting algorithm (XGBoost) operated on the entire flattened input data (dash-dotted red line); the recall and precision (which are almost identical) of a Naive classifier (persistence) which essentially returns the last observed PM10 level (dash-dotted green line); and the event rate (dotted black line), represents the precision of a classifier that constantly forecasts a dust event.

As expected, \({\Phi}_{loc}\)’s performance decreases with forecast lead time. The increase in recall (e.g., from 12 to 24 h) is traded for a sharp precision decline. Twenty-four hours ahead, \({\Phi}_{loc}\) can detect about 76% of the events (recall) or even 83% of winter–spring events, with 67% precision. For the same task, the shallow classifier achieves 67% recall and 47% precision, and the naive classifier achieves both recall and precision of about 51%. The shallow classifier is only slightly better than the naive classifier (for 24-h or longer lead time), indicating the difficulty of performing statistical learning from high-dimensional small sample-sized data. Note that the performance gap between \({\Phi}_{loc}\) and the naive/shallow classifiers increases with forecast lead time, indicating our model’s ability to generalize large-scale processes.

We evaluate the model’s forecasts by analyzing the evolution of regional PM10 fields. Figure 3 shows the average field during and before events while comparing well- and misclassified events at 24-h lead time. Well-classified events are characterized by high PM10 concentration in the northern coastal areas of Africa and the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, advancing towards Israel, as well as in local areas. These areas show much lower PM10 concentrations in the misclassified events. In misclassified events, there is no significant change in the average regional PM10 between 72 and 24 h before the dust event. A particular local change occurs less than 24 h before, indicating that the events occur on small spatiotemporal scales. In terms of ground measurements, misclassified events also show lower PM10 concentration on average (108.1 μgm−3), compared to well-classified events (145.5 μgm−3). These events are challenging to forecast more than a day in advance since they are often formed by dust emissions from local sources (e.g., the Negev or Sinai deserts) and have short-range transport; hence, large-scale meteorology holds no skill for their accurate forecasting. The findings indicate that events driven by local dynamics are the primary source of the model’s misclassification.

Comparison of the composite averages of regional PM10 fields between dust event samples that were correctly (left column), and incorrectly (right column) classified in the 24-h forecast. The first three rows represent periods in which the meteorological input is available for training. The bottom row represents the time of the event itself, which is unavailable for training.

Estimating the performance of \({\Phi}_{loc}\) based on a binary PM10 definition of dust event could be misleading. Since \({\Phi}_{loc}\) is trained to classify samples into multiple PM10 levels (see a discussion in “Discussion”), we can estimate its performance more continuously. Figure 4 shows a confusion matrix that represents the number of observed (rows) and predicted (columns) validation samples, and is ordered according to the local PM10 levels for the 24-h forecast.

The number of observed (rows) and predicted (columns) validation 3-hourly samples are presented. The rows and columns are ordered according to the local PM10 levels. Axes tick labels indicate the threshold bins that define these levels. Note that the two uppermost bins are above the threshold for dust events in this study.

As can be seen, most of the samples lie close to the confusion matrix diagonal, indicating errors of small magnitude. This suggests that the network has learned the physical phenomenon quite well. Figure 4 also illustrates the model’s improved ability to forecast extremes compared to more average levels.

Model interpretability

Model interpretability is key to gaining a better understanding of the meteorological and atmospheric conditions that favor dust events. We use the integrated gradients26 approach for attributing the contribution of the model’s input to the prediction. Here, we compute the gradients of the local PM10 level’s probability with respect to the input tensor, which inform the magnitude of the pixels’ effect on the model’s forecast. The integrated gradients of an input sample x (a meteorological tensor; see “Model”) are obtained by integrating over the gradients along a linear path from the sample to a baseline \({x}^{{\prime} }\). We compute the numerical integrated gradient approximation of pixel i (\(I{G}_{i}^{approx}\)) by accumulating the gradients over a series of 32 tensors created from interpolations between x and \({x}^{{\prime} }\):

where xi indicate the value of pixel i in tensor x. We set the baseline to be a zero tensor, representing an 18-year pixel-wise average. Analyzing the integrated gradients allows for inferring the importance of different explanatory variables to dust prediction. The approach returns attribution output at the input dimension; we can thus study how this importance is distributed over space and time for each input variable.

Figure 5a presents selected variables from the average integrated gradients field of the model 24-h forecast. The composite average is over the historical meteorology sequences of all the independent dust events (defined in “Data”); this ensures that we infer the patterns the network is “looking for” when forecasting dust events before they arrive rather than during their occurrence. The results suggest that the network has learned to scan mostly for meteorological signals that emerge in the northern regions of Africa about 3 days before the event occurs in Israel.

a Twenty-four hours forecast model’s integrated gradients with respect to each input pixel, averaged over 356 dust events preceded by a dust-free period of 96 h (independent dust events). Red and blue values represent pixel’s positive and negative attribution to model’s dust event forecasting. The sign corresponds to the anomaly sign (difference from the pixel-wise 18-year average in the physical space). The colors are scaled per explanatory variable (rows). Time frames (columns) include 72 to 24 h before the event. Variables include (top to bottom): specific humidity at 900 hPa; air temperature at 250 hPa; zonal 10-m wind; meridional 10-m wind; sea-level pressure; dust aerosol optical depth at 550 nm. b Spatiotemporal-independent importance index: The index is obtained by summing the absolute integrated gradients of model’s local PM10 forecasting with respect to the meteorological input over time and space; colors differentiate between physical measurements and the five pressure levels for the relevant variables (W, PV, Z, V, U, T, and Q) from 900 (leftmost) to 250 (rightmost) hPa. The numerical values are comparable but cannot be interpreted directly.

To obtain a comparable measure for the relative importance of different variables, such as wind speed, sea-level pressure, potential vorticity, and others, we sum the absolute integrated gradients values of independent dust events over time and space; this results in a global, time-invariant variable importance index. Figure 5b compares this importance index across the explanatory variables.

“Discussion” discusses the meteorological and atmospheric insights from our integrated gradients analysis in more detail. For completeness, we implemented other machine-learning interpretability methods, including Gradient SHAP27, DeepLIFT28, and Occlusion techniques29. The results were qualitatively similar (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study proposes a meteorology-based Deep Neural Network model for dust events forecasting in 12–72 h lead time. The model’s multi-task framework is designed to overcome unique statistical learning challenges that the data poses, by predicting regional PM10 fields (auxiliary task), in addition to the Local in situ measured PM10 forecasting (primary task). Twenty-four hours ahead, the model detects 76% of the dust events (83% of winter–spring events) at 67% precision.

Meteorological and atmospheric insights

The Middle East is subjected to dust storms that originate in several sources, with the Sahara desert being the largest. In Israel in particular, North African dust contributes 60–80% of the eolian material30, while arid and semi-arid regions to the east of Israel (e.g., the Syrian and Arabian deserts), and local dust sources (e.g., the Negev desert) contribute the rest. The atmospheric mechanisms occur on different scales; from the large scale (1000s of km) to the mesoscale (down to 1 km) and even smaller. Although a large case-to-case variability exists, certain structures of the subtropical, Mediterranean, and mid-latitude weather systems are typically organized in concert to provide the necessary dust emission and transport environments. We harness the proposed data-driven neural model to relate weather patterns and atmospheric dust levels unbiasedly and quantitatively. Specifically, we search for the meteorological conditions that indicate an increased probability of an approaching dust event.

At 24-h forecast lead time, most of the network’s attention is devoted to identifying events that originate in areas west of Israel, as demonstrated in Fig. 5a. Although the spatial and temporal focus slightly differs across variables, eastward-moving patterns of low-tropospheric cyclonic activity, relatively high temperatures, low humidity, and high AOD concentration activate the network. These findings are consistent with previous studies31.

A closer look at Fig. 5a reveals a more complex picture that is masked by averaging different types of events. For example, it can be seen that high levels of 10 m zonal wind (u10) increase dust event probability when they occur in two different regions: (i) large areas in Libya (signal starts about 48 h before the event), and (ii) smaller areas in the eastern Mediterranean, including Israel (signal starts about 24 h before the event); the reason is that the network distinguishes between strong u10 signals in the Libyan deserts that indicate an approaching large-scale dust storm, and around Israel that indicate a local event in time-space scales (sometimes during the event itself). Moreover, the meridional 10-m wind (v10) is highlighted only to the west of Israel, suggesting that both wind components are important for Saharan dust sources, compared to the dominance of the zonal near-surface winds for other sources in providing the forecast skill.

Interestingly, the network associates an increased dust event probability with high SLP levels advancing eastward along the Mediterranean Sea. We would rather expect to see an inverse correlation, as previous studies linked high dust loading in the region with a cyclone situated over the eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus Low), which is expressed in low SLP anomalies31. Since the network does not ignore the phenomena but assigns it an opposite effect, and as SLP is strongly correlated with other variables with strong explanatory power for PM10 levels (e.g., u10, v10, Z), we speculate that the network associates eastward approaching low SLP cyclones with a latent feature that reduces dust event probability (e.g., a feature correlated with seasonality, or a particular cluster of dust events). A possible interpretation is that cyclones, in general, are statistically rather correlated with precipitation in Israel32,33,34. However, a deeper understanding requires further research.

Figure 5a may be somewhat misleading about the network’s attention to events governed by dust transport towards Israel from the east. The network did learn to associate high AOD concentrations in the Red Sea coastal areas of Saudi Arabia with dust events in Israel. It is less noticeable in Fig. 5a for two reasons: first, because events originating east of Israel are relatively rare30; second, compared to the AOD signals of dust events that originated west of Israel, the eastern signals are still quite weak more than 24 h before the events itself, and usually rise later.

Figure 5b summarizes the overall importance of different variables in predicting dust events. For 24-h forecast lead time, lower-tropospheric winds, AOD, and SLP are of relatively high importance, while air temperature and specific humidity are of low importance. In geopotential height, zonal wind, meridional wind, and specific humidity, the importance usually increase in the lower-tropospheric levels. In contrast, in vertical velocity and potential vorticity it seems to peak at the mid-troposphere, suggesting that these features may provide forcing for dust emission and/or transport at lower levels by destabilization and/or downward momentum transfer. Our analysis shows that the relationship between the importance of the different variables that appears in Fig. 5b is quite stable over lead time.

The high importance of AOD and lower-tropospheric winds indicates that the network associates high probability of dust events with dynamical processes. The fact that SLP also shows high importance may suggest that the network also considers the organization of the weather system. Moreover, the low importance of temperature and specific humidity indicates that thermodynamics processes have no significant contribution to the network’s decision regarding dust events.

Implications of the dust event definition

There is no consistent definition for dust events, and studies have shown that different definitions may lead to different conclusions regarding their impact35,36,37. Numerous studies have reported high PM10 concentrations during dust events13, and there is a broad consensus on the use of PM10 concentration to approximate dust mass. A common practice is to categorize time samples based on a single PM10 threshold, sometimes in combination with weather records to define dust events30,38,39.

We could use such a definition to train the network for a binary dust event classification; instead, we train the network to model PM10 itself, i.e., to discriminate even between PM10 levels that are not considered dust events. In our understanding, learning the phenomenon of dust accumulation, a continuous atmospheric process in nature, is scientifically superior to learning arbitrary definitions. A regression setup is optimally suited for this task; however, its long-tailed distribution makes PM10 numerical value forecasting very challenging. Hence, we propose an ordinal regression setup, where the network is trained to forecast 13 equally distributed levels of PM10.

Once trained, we evaluate the network performance based on the distinct definition detailed in “Data”, which results in 11 dust-free and 2 dust event classes. Further, we discuss the statistical learning challenges that this skewed class proportions pose.

Middle Eastern dust event sequences vary significantly in duration and magnitude39. While in some sequences PM10 concentrations increase and then decrease monotonically, a significant portion is characterized by unstable duration of PM10 records, during which the measured PM levels cross the threshold value several times in a short period (sometimes less than 24 h). Skillful forecasts with 24 h or longer lead times at 3-h resolution are challenging during such events. Some studies define dust event sequences by referring to the dust-free points between dust-flagged sequences as dust events when they are close in time39. Since we do not want the network to depend on a closeness definition, we choose not to train it this way (although we use such as definition for validation only).

Challenges of deep learning with meteorological and dust data

Meteorological fields may be intuitively treated as digital images (with more than three channels) and their sequences as videos. This intuition is only partially true; Racah et al.40 mention several unique machine-learning challenges arising from the difference between climate and computer vision data. We identified three main challenges which may explain the relative paucity of research on dust forecasting using regional-scale meteorology and deep learning. We then discuss how multi-task learning might overcome these challenges.

The first challenge is that samples of meteorological fields exhibit high temporal correlations. This is because a 3-hourly sampling rate is quite fast relative to the more slowly-evolving atmospheric dynamics. This implies redundancy in the training data. Even though our dataset is supposedly large (52,560 3-hourly samples), it may not provide enough discriminative information to train an efficient neural network. For comparison, modern computer vision neural networks are trained on visual databases such as ImageNet41, which contains more than 14 million labeled images.

Second, the size and richness of the training data are effectively even smaller due to the imbalanced proportion of dust and dust-free classes. This is even clearer when considering independent dust events (defined in “Data”), consisting of only 356 autocorrelated sequences during 18 years. The redundancy and the low entropy of scarce training dust events lead to insufficient coverage of the true meteorological-dust mutual distribution. Our analysis suggests that resampling techniques for class imbalances are not helpful.

Third, unlike computer vision images, meteorological fields are geo-located, hence are shift-variant. Put differently, the fields do not retain their context after manipulations. For example, unlike cat images, axis flipping, or color jittering, will completely change the context of the meteorological fields. This characteristic implies that the input data can hardly be augmented; as further discussed, this makes learning very challenging.

The machine-learning literature offers some remedies for the problem of insufficient or small training data. One is transfer learning42, specifically, using pre-trained models. A pre-trained network is trained on an extensive visual database in computer vision before fine-tuning a specific dataset. As the statistical properties of climate data and natural images are very different, using available pre-trained networks is usually unsuccessful40; our analysis confirms this hypothesis. Another possible remedy is data augmentation43, where input data is slightly modified, or synthetically created from real samples, to increase the training data. Common techniques for computer vision include position augmentation (e.g., cropping, scaling, rotation) and color augmentation (e.g., brightness, contrast, or saturation adjustment). Meteorological fields’ shift variance makes these techniques inefficient.

Multi-task learning

Multi-task learning is a machine-learning paradigm that aims to solve multiple related learning tasks simultaneously. Here, we train a CNN encoder to learn a representation of the meteorological time frame inputs. This representation is then shared between the local task, which ultimately interests us, and the regional tasks, which serves as an auxiliary task44.

We suggest a multi-task setting to overcome the scarcity of independent real-world dust events and the difficulty of generating informative meteorological augmentations, as discussed above. To explain why multi-task learning is beneficial, we follow the lines of Ruder45, who reviews its underlying mechanisms45. First, since local and regional tasks introduce different noise patterns, our setting contains an implicit data augmentation. That is, it causes learning a representation that ignores the data-dependent noise of two tasks rather than one. Second, when training with high-dimensional small sample-sized input, attention focusing is essential; multi-task learning helps the model focus on regional-scale meteorological features that matter. Third, multi-task learning leverages valuable information from correlated tasks to improve generalization capability. Here, the encoder network can be considered as a feature extractor that introduces an inductive bias46 toward a regional-scale and more general view; i.e., it learns representations that also consider the regional dynamics of dust. This may help the model generalize dust events with meteorological patterns that are locally rare but globally more common. Fourth, multi-task learning acts as a regularization mechanism that makes the model less prone to overfitting.

Model architecture

Despite the differences pointed out between the model’s input and classical videos, we found that video classification architectures are most suitable for our problem. Therefore, we implemented a typical separable architecture (CNN for spatial frames, FC for time sequence). We found that an FC network, which operates on the entire sequence, outperforms other architectures, including Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, which exhibit temporal dynamic behavior.

Along with the model architecture, we examined different lengths and frequencies of the time series input. We found that a 96-h history of 12-h time intervals, i.e., eight frames per sample, is optimal in terms of local dust forecasting performance. This structure compromises between long sequences of correlated frames that flood the network, and short or too-sparse sequences that prevent generalization.

The autoencoder network, which is composed of convolutional (encoder) and deconvolutional (decoder) layers, is an instance of a U-Net architecture47, initially proposed for image pixel-wise segmentation. While a low compression ratio (i.e., larger code size) improves the regional task performance, the effect on the local task is bidirectional: it enriches the frame’s representation but increases the risk of overfitting. We found that a code size of 512 elements is optimal for the local task performance.

The rationale for adding auxiliary tasks is discussed above. The regional task seems a natural choice since it requires learning relevant regional-scale spatial features. Yet, other tasks may be helpful. For instance, we examined assigning the autoencoder a self-supervision task, where it is requested to reconstruct the original input. In another attempt, we examined auxiliary tasks that process whole sequences to learn inherent spatiotemporal representations from dynamic inputs. For example, predicting the future t + k regional PM10 field or sorting the shuffled input sequences. None of these proved better than the proposed architecture.

Methods

Data

Half-hourly PM10 measurements from 30 ground air quality monitoring stations for 18 years, from January 2003 through 31 December 2020, were retrieved from the Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection (MOEP) database (https://www.svivaaqm.net). The stations are scattered over an area of about 200 km by 50 km, covering its Mediterranean coastline and central mountains’ western slopes. Stations’ spatial distribution tends towards the populated coastal areas and the central cities (Fig. 6a). PM10 measurements were conducted using Tapered-Element Oscillating Microbalance (TEOM) instruments operated according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA) guidelines48. Recent years show a certain decrease in PM10 concentrations, mainly in the frequency of extremes (Fig. 6b), measured primarily during winter and spring (Fig. 6c).

a The spatial distribution of the ground PM10 monitoring stations, and the median measurement over station’s operation period (colorbar). b One-year moving averages of selected PM10 quantiles (95th, 75th, 50th, 25th, 5th), each measured on 3-hourly basis. c Monthly averages of the same PM10 quantiles appears in (b). The 65.2 μgm−3 threshold defining dust events is marked (red horizontal line).

In consistency with previous studies49, we define a dust event when the local PM10 exceeds 2 standard deviations above the background concentration (average local PM10 at the summer season), which results in a threshold of 65.2 μgm−3. “Discussion” discusses the model implications of this definition.

Considering 3-hourly averages, there are 7019 events, roughly 13% of the studied period. Out of these, the average PM10 concentration is 142.2 μgm−3, the median is 93.1 μgm−3, and the standard deviation is 159.8 μgm−3. As can be seen in Fig. 6c, most of the events occur in the winter and spring months (33.7% and 36.5%, respectively), less in the fall (25.5%), and only a few in the summer (4.1%).

For model interpretability (see “Model interpretability”), we define independent dust events as sequences of 3-hourly dust events preceded by a dust-free period of at least 96 h. This definition allows focusing on new, rather than mixed, events by examination of the atmospheric conditions during the 96 h prior to the onset of the events. During the studied period, we observed 356 independent dust events.

Regional atmospheric data are extracted for the region covering the Mediterranean, the Saharan desert, and the Arabian Peninsula (19-43N, 2-51E), essentially encompassing all sources of dust potentially transported to Israel. Variables and pressure ranges selection is based on prior scientific knowledge of the quantities that may be potentially relevant to dust events in the region4,5. They were retrieved from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis 5th Generation (ERA5) database50 and include geopotential height (Z); zonal wind (U); meridional wind (V); vertical velocity (W); potential vorticity (PV); specific humidity (Q); and air temperature (T), all taken at the five pressure levels of 250, 500, 700, 850, and 900 hPa; along with sea-level pressure (SLP). Additional 2-dimensional variables over the same domain were extracted from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) reanalysis database51 and include zonal and meridional wind at 10 m (u10, v10); Total Column Water Vapour (TCWV); Dust Aerosol Optical Depth at 550 nm (AOD); and PM10 (regional PM10).

For the local task, 3-hourly averages from the 30 stations were computed (local PM10). Samples were omitted if 50% of the averaged data (stations or time points) were missing. Overall, 52,245 3-hourly samples remained.

For the regional task, both ERA5 and CAMS regional data were interpolated to 0.5-degree horizontal resolution, resulting in 49 × 99 gridded fields. As CAMS data are taken 6-hourly, we temporally interpolated it linearly to match the 3-hourly resolution of the ERA5 and the local PM10 data. Missing spatial data (less than 0.5% of the pixels), e.g., due to surface intersection, was imputed using cubic splines interpolation.

All gridded fields are standardized (mean removed and divided by standard deviation) at the pixel level before being transferred to the neural model. Means and standard deviations were computed over the entire period; data can therefore be interpreted in terms of anomalies from the 18-year average.

Model

Figure 7 illustrates the network’s architecture. Let \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}\) denote the space of the meteorological input tensors (for readability, we sometimes omit the atmospheric adjective of the input). \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}\) contains tensors of size 40 × 49 × 99, which consist of all gridded fields except regional PM10. Also, let \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) denote the space of regional PM10 fields; \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) the set of possible time features (month, day of week, and hour); and \({{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\) the set of local PM10 levels, where \(| {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}| =13\). Measurements are taken at 3-hourly timestamp t. We denote the state of t by st = (xt, ft, yt), where \({x}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{X}}}}\), \({f}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\), and \({y}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\).

For every timestamp t, meteorological input tensor xt, time feature ft, and in situ PM10 level yt are passed to an encoder network which returns a code ct. The encoder is composed of stacked CNN layers which consist of batch-norms (BN), convolutions (Conv) with ReLU activations; and transformers + residual blocks (ResBlock) which consist of (spatial) positional encoding, a multi-head attention network, and a feed-forward network; lastly fully connected (FC) layers transform the output into a 512-element vector, ct. The decoder network receives ct and returns a regional PM10 prediction \({\hat{z}}_{t}\). The decoder is composed of stacked CNN layers and deconvolutional (deConv) layers. A sequence of codes ct−N, . . . , ct are transferred to the classifier network which returns a single local PM10 forecast \({\hat{y}}_{t+k}\). The classifier is composed of a concatenation (Concat) of N codes, dropout (Drop) with rate 0.5, BN, FC, and ReLU activation, which follows an additional FC layer with a softmax activation. The local and regional tasks are solved simultaneously through optimizing a weighted loss.

Our interest is in learning a mapping \({{{\Phi }}}_{loc}:{[{{{\mathcal{X}}}}\times {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\times {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}]}^{N}\to {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\), which given an input sequence of N states outputs the k-hour forecast of local PM10 level, \({\hat{y}}_{t+k}\in {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\), where k ∈ {12, 24, . . . , 72}. For reasons discussed in “Discussion”, we do not learn \({\Phi}_{loc}\) directly, but simultaneously with \({{{\Phi }}}_{reg}:{{{\mathcal{X}}}}\times {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\times {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\to {{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\). Namely, \({\Phi}_{reg}\) receives a state st, and outputs the predicted corresponding regional PM10 field, \({\hat{z}}_{t}\in {{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\); it is thus invariant to time sequences.

\({\Phi}_{reg}\) is constructed by stacking an encoder and a decoder in an autoencoder architecture. The encoder network consists of a CNN with transformer encoder layer52, made up of self-attention and feed-forward networks, and residual blocks53. It learns the spatial features of the meteorological input. Additionally, it includes two functions that map the discrete values of ft and yt into vectors of continuous numbers, thus embed timestamp and current local PM10 information. These embeddings are concatenated to the CNN output. The encoder receives a state, st, and returns its code, namely, a vector of 512 elements we denote by ct. The decoder network learns to decode ct into zt. It is composed of learnable transposed convolutional layers, also known as deconvolutions54 which up-sample the code back to a field of similar spatial dimensions as the meteorological tensors.

\({\Phi}_{loc}\) consists of two parts: an encoder and a classifier network. The encoder described above is common to \({\Phi}_{reg}\) and \({\Phi}_{loc}\); for each t, it transforms the sequence \({\{{s}_{i}\}}_{i = t-N}^{t}\), which encapsulates t’s N-length meteorological history, into a sequence of codes \({\{{c}_{i}\}}_{i = t-N}^{t}\). For simplicity, we denote these sequences by \({s}_{t}^{N}\) and \({c}_{t}^{N}\), respectively. The classifier network concatenates the code sequence to a single vector, then passes it through two FC layers, followed by ReLU and sigmoid activations, respectively. Eventually, for each t, the classifier network returns a vector of probabilities attributed to each local PM10 level at timestamps t + k and outputs the level with the highest probability.

The above architecture uses the encoder codes \({c}_{t}^{N}\), to forecast the future local PM10 level yt+k, and to predict the current regional PM10 maps \({z}_{t}^{N}={\{{z}_{i}\}}_{i = t-N}^{t}\). As follows, the encoder learns a meteorological compression that preserves two information types. For the local task, it saves local-scale dynamics features necessary to forecast the future local PM10. For the regional task, it saves regional-scale features necessary for reconstructing the regional PM10.

To take advantage of the ordinal behavior of yt, \({\Phi}_{loc}\) is trained by minimizing a soft ordinal regression55 (SORD) loss function, which penalizes for the distance of the error in terms of \({{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\) levels. It is formulated as a cross-entropy loss, only replacing the one-hot representation with an operator δ(y), that encodes the distance (in terms of probability) of every PM10 level \(i\in \{1,...,| {{{\mathcal{Y}}}}| \}\) from the true level y:

where \({{{\Phi }}}_{loc}{({s}_{t}^{N})}_{i}\) is the predicted probability for level i, and δ(y)i is the corresponding element in the distance-based SORD encoding vector55.

\({\Phi}_{reg}\) is trained by minimizing the pixel-wise mean squared error of the decoder’s prediction from the regional PM10 field:

Finally, the multi-task model is trained end-to-end by minimizing:

where λ is a constant hyperparameter representing the regional task weight.

A training batch consists of 32 random sampled sets of tensors \({s}_{t}^{N},{z}_{t}^{N}\) and scalars yt+k. For each batch, the encoder computes 32*N codes, regardless of their sequences, and in parallel passes them to the decoder and the classifier networks. The decoder outputs 32*N regional PM10 fields. Thus \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{MSE}\) is computed 32*N times. The classifier combines the codes back into sequences, and outputs 32 forecasts; thus \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{SORD}\) is computed 32 times. Optimization is performed using the Adam Optimizer56. A grid search provided λ = 0.05.

Local PM10 values vary only in time (not in space) and have short-range temporal dependence. In order to keep the sets independent, performance evaluation was performed based on long non-overlapping series. Specifically, we split the data into training and validation sets by randomly sampling a third of the calendar years for validation, while omitting overlapping timestamps.

Although \({\Phi}_{loc}\) classifies PM10 levels, we are primarily interested in the highest levels. The small proportion of dust events makes accuracy a misleading metric; instead, we measure performance in terms of recall and precision:

where TP is the number of dust events samples that were correctly classified as events, FN is the number of dust events samples that were mistakenly classified as dust-free, and FP is the number of dust-free samples that were mistakenly classified as dust events. Note that recall and precision have an inverse relationship.

Data availability

All data that support the findings in this study is freely available. CAMS data can be downloaded from Atmosphere Data Store at https://atmosphere.copernicus.eu/data. ERA5 data can be downloaded at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era5. In situ PM10 measurements can be downloaded at https://www.svivaaqm.net.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Ginoux, P., Prospero, J. M., Gill, T. E., Hsu, N. C. & Zhao, M. Global-scale attribution of anthropogenic and natural dust sources and their emission rates based on modis deep blue aerosol products. Rev. Geophys. 50 (2012).

Middleton, N. J. Desert dust hazards: a global review. Aeolian Res. 24, 53–63 (2017).

Goudie, A. S. Desert dust and human health disorders. Environ. Int. 63, 101–113 (2014).

Alpert, P., Osetinsky, I., Ziv, B. & Shafir, H. Semi-objective classification for daily synoptic systems: application to the eastern Mediterranean climate change. Int. J. Climatol.: J. Royal Meteorol. Soc. 24, 1001–1011 (2004).

Dayan, U., Ziv, B., Shoob, T. & Enzel, Y. Suspended dust over southeastern Mediterranean and its relation to atmospheric circulations. Int. J. Climatol.: J. Royal Meteorol. Soc. 28, 915–924 (2008).

Basart, S., Pérez, C., Nickovic, S., Cuevas, E. & Baldasano, J. Development and evaluation of the BSC-DREAM8b dust regional model over northern Africa, the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 64, 18539 (2012).

Kukkonen, J. et al. A review of operational, regional-scale, chemical weather forecasting models in Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 1–87 (2012).

Knippertz, P. & Todd, M. C. Mineral dust aerosols over the Sahara: meteorological controls on emission and transport and implications for modeling. Rev. Geophys. 50 (2012).

Zhong, S. et al. Machine learning: new ideas and tools in environmental science and engineering. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12741–12754 (2021).

Rolnick, D. et al. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 55, 1–96 (2022).

Reichstein, M. et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven earth system science. Nature 566, 195–204 (2019).

Chae, S. et al. Pm10 and pm2. 5 real-time prediction models using an interpolated convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–9 (2021).

Krasnov, H., Katra, I., Koutrakis, P. & Friger, M. D. Contribution of dust storms to pm10 levels in an urban arid environment. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 64, 89–94 (2014).

Jiang, H. et al. Dust storm detection of a convolutional neural network and a physical algorithm based on fy-4a satellite data. Adv. Space Res. 69, 4288–4306 (2022).

Shi, L., Zhang, J., Zhang, D., Igbawua, T. & Liu, Y. Developing a dust storm detection method combining support vector machine and satellite data in typical dust regions of Asia. Adv. Space Res. 65, 1263–1278 (2020).

Kang, S., Kim, N. & Lee, B.-D. Fine dust forecast based on recurrent neural networks. in 2019 21st International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), 456–459 (IEEE, 2019).

Shtein, A. et al. Estimating daily and intra-daily pm10 and pm2. 5 in Israel using a spatio-temporal hybrid modeling approach. Atmos. Environ. 191, 142–152 (2018).

Harba, H. S., Harba, E. & Farttoos, M. Prediction of dust storm direction from satellite images by utilized deep learning neural network. in 2020 6th International Engineering Conference “Sustainable Technology and Development"(IEC), 179–184 (IEEE, 2020).

Ebrahimi-Khusfi, Z., Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R. & Mirakbari, M. Evaluation of machine learning models for predicting the temporal variations of dust storm index in arid regions of Iran. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 12, 134–147 (2021).

Boroughani, M. et al. Application of remote sensing techniques and machine learning algorithms in dust source detection and dust source susceptibility mapping. Ecol. Inform. 56, 101059 (2020).

Kowalski, P. A., Sapala, K. & Warchalowski, W. Pm10 forecasting through applying convolution neural network techniques. Air Pollut. Stud. 47, 31–43 (2020).

Nidzgorska-Lencewicz, J. Application of artificial neural networks in the prediction of pm10 levels in the winter months: a case study in the Tricity agglomeration, Poland. Atmosphere 9, 203 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Machine learning based algorithms for global dust aerosol detection from satellite images: inter-comparisons and evaluation. Remote Sens. 13, 456 (2021).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Machine learning 28, 41–75 (1997).

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A. & Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. in International Conference on Machine Learning, 3319–3328 (PMLR, 2017).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4765–4774 (2017).

Shrikumar, A., Greenside, P. & Kundaje, A. Learning important features through propagating activation differences. in International Conference on Machine Learning, 3145–3153 (PMLR, 2017).

Kumar Singh, K. & Jae Lee, Y. Hide-and-seek: forcing a network to be meticulous for weakly-supervised object and action localization. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 3524–3533 (IEEE, 2017).

Krasnov, H., Katra, I. & Friger, M. Increase in dust storm related pm10 concentrations: a time series analysis of 2001–2015. Environ. Pollut. 213, 36–42 (2016).

Kalkstein, A. J., Rudich, Y., Raveh-Rubin, S., Kloog, I. & Novack, V. A closer look at the role of the cyprus low on dust events in the negev desert. Atmosphere 11, 1020 (2020).

Saaroni, H., Halfon, N., Ziv, B., Alpert, P. & Kutiel, H. Links between the rainfall regime in Israel and location and intensity of Cyprus lows. Int. J. Climatol.: J. Royal Meteorol. Soc. 30, 1014–1025 (2010).

Raveh-Rubin, S. & Wernli, H. Large-scale wind and precipitation extremes in the Mediterranean: a climatological analysis for 1979–2012. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 2404–2417 (2015).

Raveh-Rubin, S. & Wernli, H. Large-scale wind and precipitation extremes in the Mediterranean: dynamical aspects of five selected cyclone events. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 142, 3097–3114 (2016).

Kushta, J., Pozzer, A. & Lelieveld, J. Uncertainties in estimates of mortality attributable to ambient pm2. 5 in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 064029 (2018).

Tong, D. Q. et al. Dust storms, valley fever, and public awareness. GeoHealth 6, e2022GH000642 (2022).

Sarafian, R., Kloog, I. & Rosenblatt, J. D. Optimal-design domain-adaptation for exposure prediction in two-stage epidemiological studies. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 1–8 (2022).

Achilleos, S. et al. Spatio-temporal variability of desert dust storms in eastern Mediterranean (Crete, Cyprus, Israel) between 2006 and 2017 using a uniform methodology. Sci. Total Environ. 714, 136693 (2020).

Sorek-Hamer, M., Stupp, A., Alpert, P. & Broday, D. M. et al. Characteristics of the east Mediterranean dust variability on small spatial and temporal scales. Atmos. Environ. 120, 51–60 (2015).

Racah, E. et al. Extremeweather: a large-scale climate dataset for semi-supervised detection, localization, and understanding of extreme weather events. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 3402–3413 (2017).

Russakovsky, O. et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Computer Vision 115, 211–252 (2015).

Zhuang, F. et al. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc. IEEE 109, 43–76 (2020).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 6, 1–48 (2019).

Liebel, L. & Körner, M. Auxiliary tasks in multi-task learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.06334 (2018).

Ruder, S. An overview of multi-task learning in deep neural networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.05098 (2017).

Mitchell, T. M. The Need for Biases in Learning Generalizations (Department of Computer Science, Laboratory for Computer Science Research, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, 1980).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-assisted Intervention, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

EPA. Quality Assurance Handbook for Air Pollution Measurement Systems: “volume II: Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Program" (United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), RTP, NC, 2017).

Vodonos, A. et al. The impact of desert dust exposures on hospitalizations due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Air Quality Atmos. Health 7, 433–439 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The era5 global reanalysis. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Inness, A. et al. The cams reanalysis of atmospheric composition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 3515–3556 (2019).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Zeiler, M. D., Krishnan, D., Taylor, G. W. & Fergus, R. Deconvolutional networks. in 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2528–2535 (IEEE, 2010).

Roy, S. et al. Deep learning for classification and localization of covid-19 markers in point-of-care lung ultrasound. IEEE Transact. Medical Imaging 39, 2676–2687 (2020).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Shai Bagon for his comments and ideas and Vered Silverman for extracting and preparing the reanalysis data. The European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts and Israeli Meteorological Service are acknowledged for providing access to ERA5. The research was partially supported by a research grant from the Maggie Kaplan Research Fund, by the Israeli Council for Higher Education (CHE) via the Weizmann Data Science Research Center, and by the Helen Kimmel Center for Planetary Science at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. and D.N. conceived of the presented idea; R.S. developed the theory with support from D.N. and performed the computations; D.N. built and processed the data; S.R.R. and Y.R. verified the analytical methods, the scientific insights, and supervised the findings of this study; R.S. wrote the manuscript with support from D.N., S.R.R., and Y.R.; V.A. programmed the visualization and explanation tools. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarafian, R., Nissenbaum, D., Raveh-Rubin, S. et al. Deep multi-task learning for early warnings of dust events implemented for the Middle East. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 23 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00348-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00348-9

This article is cited by

-

Deriving ozone and PM pollution vertical profiles using lightweight, cost-effective sensors and deep learning

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)