Abstract

Wintertime meteorological conditions are usually unfavorable for ozone (O3) formation due to weak solar irradiation and low temperature. Here, we observed a prominent wintertime O3 pollution event in Shijiazhuang (SJZ) during the Chinese New Year (CNY) in 2021. Meteorological results found that the sudden change in the air pressure field, leading to the wind changing from northwest before CNY to southwest during CNY, promotes the accumulation of air pollutants from southwest neighbor areas of SJZ and greatly inhibits the diffusion and dilution of local pollutants. The photochemical regime of O3 formation is limited by volatile organic compounds (VOCs), suggesting that VOCs play an important role in O3 formation. With the developed O3 formation path tracing (OFPT) approach for O3 source apportionment, it has been found that highly reactive species, such as ethene, propene, toluene, and xylene, are key contributors to O3 production, resulting in the mean O3 production rate (PO3) during CNY being 3.7 times higher than that before and after CNY. Industrial combustion has been identified as the largest source of the PO3 (2.6 ± 2.2 ppbv h−1), with the biggest increment (4.8 times) during CNY compared to the periods before and after CNY. Strict control measures in the industry should be implemented for O3 pollution control in SJZ. Our results also demonstrate that the OFPT approach, which accounts for the dynamic variations of atmospheric composition and meteorological conditions, is effective for O3 source apportionment and can also well capture the O3 production capacity of different sources compared with the maximum incremental reactivity (MIR) method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution has caused widespread concern due to human health risks and economic losses1,2. Over the past few years, the Chinese government has made great efforts to improve air quality, especially by reducing fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations. From 2013 to 2017, PM2.5 concentrations decreased by more than 30% across the country3. However, ozone (O3) concentrations show an increasing trend (around 2.9 ppbv yr−1) in many regions over the period 2013–20194.

Tropospheric O3 is produced via the photochemical cycle of nitrogen monoxide (NO)-O3-nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which is sped up in the presence of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), resulting in an accelerated O3 production rate in the environment5. Xiong et al.6 investigated the VOCs pollution characteristics in Chengdu and found that combustion sources contributed more to VOCs in winter (23.9%) than that in summer (12.1%), and the main sources of VOCs were natural gas (NG)/liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) usage and industry. Seco et al.7 conducted seasonal (winter and summer) measurements at a forest site and found that biogenic emissions of isoprene and monoterpenes occurred only during the warmest summer months. Recent studies have found that wintertime VOC concentrations in Heibei province are 1.5 to 2 times higher than those in summer8,9. Therefore, the potential source of O3 in winter should be different from that in summer because O3 pollution in most Chinese cities is located in a VOC-limited regime and the emission sources and components of VOCs vary greatly10,11. In addition, photochemical reactions greatly depend on solar radiation and temperature12. Highly reactive VOCs (kOH > 10−11 cm3 molecule−1 s−1, photochemical age assumed to be 12 h) may lose ~80% before being sampled due to photochemical loss in summer13. Previous studies investigated photochemical losses of VOCs in summer and found that total VOCs were underestimated by about 18.4–23.3% due to photochemical loss, while highly reactive species (isoprene, ethene, propene) were underestimated by about 30.0–61.9%14,15. Thus, the importance of these highly reactive VOCs to O3 formation might be overlooked in summer due to the photochemical losses based on observation-based modeling (OBM)16,17. The specific atmospheric conditions such as weak solar radiation and low temperature in winter should provide us a good opportunity to characterize the highly reactive VOCs, in particular, their roles in O3 production. However, most of the previous studies have mainly focused on summertime O3 pollution, while wintertime O3 pollution has attracted insufficient attention12,18.

Shijiazhuang (SJZ), the provincial capital of Hebei, is an important industrial base with 10 million residents. It is also an important site in the southwest transport channel of air pollutants in the North China Plain (NCP)19. Guan et al.20 investigated the characteristics and sources of summertime VOCs in Shijiazhuang using an offline sampling method. They found that oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) accounted for 37.9% of the total VOCs, followed by alkanes (33.9%), unlike the results in Beijing21,22, Chengdu6, etc., where alkanes had the highest contribution (42.6–44.5%) to total VOCs. Meanwhile, petrochemical (24.2%) and other industrial sources (15.2%) were the main emission sources of VOCs in SJZ20. However, less attention has been paid to O3 pollution in SJZ at present although it is an urgent issue from the perspective of both regional transport of air pollutants and local photochemistry.

When we implement O3 pollution control, it is crucial to determine the main regional and sectoral sources of O323. The trajectories analysis of air masses can identify the regional sources of surface O3, but not account for the chemical processes24,25, thus limiting its application in quantifying O3 sources. Emission-based model (EBM), which predicts the transport and photochemical reactions of O3 as well as its precursors utilizing air quality models with a known emissions inventory, is a powerful tool and has been widely used for O3 source apportionment26,27. The OBM, which simulates O3 formation processes constrained by measurements of the concentrations of O3, oxides of nitrogen (NOx), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrous acid (HONO), VOCs, the photolysis rate constant (J), temperature (T), pressure (P), and relative humidity (RH), can avoid the uncertainties caused by emission inventories and the simulated dynamics of the boundary layer when compared with the EBM28. Thus, it has attracted much attention in China, in particular, due to the relatively insufficient research on emission inventories25. It has been well recognized that VOC species have different reactivities, resulting in different O3 production rates (PO3). However, previous studies have rarely quantified the contribution of different VOC sources to O3 production rates29,30. At present, a propylene-equivalent concentration method and a maximum incremental reactivity (MIR) method are usually used to calculate the reactivity of VOCs and the contributions of chemical species and sources to the ozone formation potential (OFP)31,32, because the production of O3 is VOCs-limited in the most of urban areas of China33,34. These two methods estimate the amount of O3 formed under optimum or ideal conditions, which may differ from the amount formed in the actual atmosphere. Ling et al.35 proposed an O3 source apportionment method combining positive matrix factorization (PMF) and OBM simulations, in which the OBM simulation was driven by the PMF extracted concentrations to calculate the relative O3 reduction efficiency (RORE) or relative incremental reactivity (RIR) of a single given VOC source. However, using a given VOC source as OBM input may result in differences in both the concentrations of free radicals and PO3 in the model from that in the actual situation. Therefore, there is a need to develop a more reliable method to apportion O3 sources and understand wintertime ozone pollution.

In this study, we propose an ozone formation path tracing (OFPT) approach for PO3 in the OBM under real observational conditions and combine it with the VOCs-PMF to quantify the sources of the O3 production rate. Based on an observation campaign in SJZ during the Chinese New Year (CNY) in 2021, we investigated the O3 pollution in SJZ from the perspective of both regional transport of air pollutants and local photochemistry. The contributions of anthropogenic VOCs, especially aromatics and alkenes with high reactivity, to O3 production and formation sensitivity regime were discussed. The OFPT method was used to identify the O3 sources from the perspective of O3 production. Meanwhile, the OFPT method was compared with the traditional one based on the MIR method. To the best knowledge, this is the first time report about the wintertime O3 pollution in SJZ and source apportionment in light of the PO3 based on the OFPT method. Our results highlight the role of highly reactive VOCs from industrial emissions in O3 pollution in SJZ.

Results

Air quality and meteorological conditions during the observation

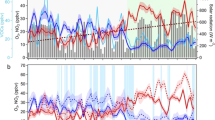

Figure 1 shows the time series of meteorological parameters, including RH, T, solar radiation (SR), wind speed (WS), and wind direction (WD), and air pollutants (VOCs, NOx, O3, SO2, PM2.5) during our observations. The RH was 45.0 ± 10.8% during the Spring Festival period, which was higher than that before and after CNY (22.8 ± 14.7% and 28.0 ± 18.2%, respectively). The concentration of PM2.5 showed a similar trend to the RH, i.e., higher (187.3 ± 54.7 µg m−3) during CNY than that before and after CNY (46.7 ± 22.2 and 41.6 ± 25.3 µg m−3, respectively). The temperature ranged from 0 to 26.9 °C, with a mean value of 8.3 ± 6.3 °C during the observation period. The maximum daily 8-hour average (MDA8) O3 concentration increased significantly (P < 0.05) during CNY (48.8 ± 3.7 ppbv) when compared with that before (40.3 ± 3.2 ppbv) and after CNY (38.4 ± 2.7 ppbv), respectively. The maximal hourly O3 concentration even reached 75.5 ppbv during CNY, which is close to the Chinese second-order air quality standard (160 µg m−3, corresponding to 77.3 ppbv at 281 K and 1008 hPa). The WS was 1.5 ± 0.7 m s−1 during CNY, which was slightly lower than 1.7 ± 0.7 m s−1 before and 2.2 ± 0.9 m s−1 after CNY. Small wind speed is favorable for the accumulation of pollutants. Previous studies found that local emissions and chemistry significantly contribute to the accumulation of air pollutants when wind speeds were below 2 m s−1 36,37. This implies that local emissions and chemistry may be the important contributors to O3 pollution during CNY. In addition, O3 pollution usually occurs in warm seasons under conditions of intense solar radiation and high ambient temperature38. The increased O3 concentration during CNY implies vigorous photochemistry although the meteorological conditions (e.g., lower T and SR) are not in favor of the occurrence of O3 pollution in winter.

As can be seen in Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 1, the concentrations of alkanes, alkenes, alkyne, and aromatics increased significantly (P < 0.05) during CNY, with mean values of 23.3 ± 7.3, 7.3 ± 3.6, 5.2 ± 1.5, and 3.5 ± 1.7 ppbv, respectively, when compared with those before and after CNY period. The NOx concentrations showed a slightly decreasing trend with the mean values of 21.7 ± 11.3, 20.9 ± 9.9, and 17.5 ± 12.3 ppbv before, during, and after CNY, respectively. The NO concentration was lower during CNY than that before and after CNY. This may be attributed to the enhanced generation rates of alkyl peroxide radicals (RO2) and hydrogen peroxide radicals (HO2) from VOCs during CNY, which subsequently will promote the conversion of NO to NO2. This is generally consistent with the slightly higher NO2 concentrations during CNY than that before and after CNY. It should be noted that the NOx concentration is slightly higher during CNY compared to that (17.2 ± 7.3 ppbv) in the previous 4 days (Fig. 1e). This highlights the important role of VOCs in O3 pollution during CNY. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, CO concentrations increased significantly during CNY when compared with those before and after CNY, which implies the intensive combustion emissions from industry and/or residents in Shijiazhuang39.

Regional transport vs local photochemistry

Although the mean wind speed on the surface was lower than 2 m s−1 during our observations, regional transportation of air pollutants (O3 and VOCs) might still be important. Figure 2 shows the potential source contribution of VOCs and O3 in different periods. VOCs and O3 have similar patterns of geographical sources regardless of the observation period although a slight difference is observable. If O3 mainly results from transport, it should show a different distribution pattern from that of VOCs, which are mainly from local emissions. Thus, the observed O3 pollution event at our observation site should be highly related to the photochemistry of VOCs besides the transport of O340. Figure 2c, f and i show the fields of geopotential height and wind at a pressure of 925 hPa before, during, and after CNY, respectively. It can be seen that the pressure system in the NCP was influenced by the abnormal weakening of the West Pacific subtropical high-pressure system in the southern regions (Supplementary Fig. 2) and the temporary appearance of a low-pressure system in the northern regions of the observation site (dash box in Fig. 2f). Subsequently, the clean air masses from the northwest monsoon in the observation area are weakened, resulting in unfavorable dilution of local pollutants. Meanwhile, the area between the trough of low pressure and the ridge of high pressure is not conducive to local pollutants diffusion. This unfavorable meteorological condition can be further analyzed using the results of air mass trajectory.

The PSCF analysis of VOCs (a), O3 (b), and the field of geopotential height and wind (c) before CNY. d–f The PSCF analysis of VOCs (d), O3 (e), and the field of geopotential height and wind (f) during CNY, respectively. g–i The PSCF analysis of VOCs (g), O3 (h), and the field of geopotential height and wind (i) after CNY, respectively. The color bar in the left (a, d, g) and middle (b, e, h) columns indicates the possibility of the source, ranging from 0 to 1. The geopotential height in the right column (c, f, i) is at 925 hPa.

Supplementary Fig. 3a, d and g show the 24-h backward trajectories of air mass at a height of 0.5 km before, during, and after CNY, respectively. The air mass was clustered to 3 trajectories in these three periods, according to the variation of the total variation of spatial (TVS) to a possible number of clusters (Supplementary Fig. 3b, e, h). Before and after CNY, long-distance trajectories from north-related directions (routes 1 and 1, 2, respectively) contributed 63.5–74.5% to the air masses (Supplementary Fig. 3a, g), while south and east directions (routes 2 and 3) with short-range trajectories dominated the air masses during CNY (69.1%, Supplementary Fig. 3d). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3f, clusters 2 and 3 were near the ground surface with short-range trajectories during CNY. Meanwhile, cluster 1 and clusters 1&2 were transmitted at a high height during the periods before and after CNY, respectively. Long-range transport generally has higher wind speeds and a stronger dilution ability to air pollutants than short-range transport41. It should be noted that the southward ground surface winds only accounted for 24.0% during CNY (Fig. 1b), while the southward trajectories account for 45.8% during the same period (Supplementary Fig. 3d). This should be ascribed to their different heights, i.e., the start point of the air mass trajectory is 500 m from the ground (much less susceptible to topographic influence), while the wind direction is measured at 25 m at the observation station.

Interestingly, both the concentrations of O3 and VOCs well correlated with the relative contribution of short-range air masses (Supplementary Fig. 4). The highest contributions of the short-range air masses to VOCs and O3 were observed during CNY. In addition, high O3 concentrations generally come from the south direction, which coincided with the pollution distribution in SJZ (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). These results illustrate that the O3 pollution event during CNY should be mainly affected by the low-speed air mass intrusion from the southern regions of SJZ, leading to the accumulation of air pollutants. This can be ascribed to the fact that (1) the sudden changes in the meteorological system altered the pressure and wind fields at the observation site, which provides favorable conditions for the accumulation and reaction of pollutants during CNY; (2) the local primary emission sources of VOCs were located in the south of SJZ (Supplementary Fig. 6); (3) the urban areas of SJZ are semi-surrounded by the Taihang Mountains, and when east or south winds prevail (during CNY), local pollutants are blocked by the mountains, resulting in a constant accumulation of pollutants42; (4) the crowded industries with high emission rates of air pollutants in the neighboring areas43. Large-scale changes in meteorological conditions can affect local air quality. Therefore, unfavorable meteorological and topographic conditions lead to the occurrence of wintertime O3 pollution, which provides favorable conditions for the photochemistry of VOCs.

Ozone formation sensitivity and contribution of reactive VOCs to O3 formation

The empirical kinetic modeling approach (EKMA) curves are widely used to reveal the dependence of O3 formation on its precursors after the local pollution levels and meteorological parameters have been accounted for. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, the model well-predicted O3 concentrations with an R2 of 0.97 during the observations. Meanwhile, the simulated OH and HO2 concentrations are also at reasonable levels44. Figure 3a shows the O3 formation sensitivity during our observations. O3 formation was located in a VOC-limited regime as expected during our observations (Fig. 3a), while the ratio of VOCs/NOx during CNY was significantly higher than those before and after CNY. During CNY overlapping the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, it was also found that an emission reduction of NOx led to an increase in O3 concentrations with a constant emission of VOCs in the North China Plain18. This means that O3 pollution during CNY in this study should be mainly ascribed to the enhanced VOC emissions. Furthermore, the emitted highly reactive species may also react with nitrate radicals (NO3) in the afternoon when NO concentrations are low, which reduces the atmospheric NOx concentration and leads to a weak titration capability (Supplementary Fig. 8)45.

Figure 3b–d shows the mean diurnal variations of the PO3 and the DO3 during the three periods. The mean O3 production rates (PO3) were 2.2 ± 1.6, 6.4 ± 5.3, and 1.4 ± 1.2 ppbv h−1 before, during, and after CNY, respectively. The O3 production rates before and after CNY (Fig. 3b, d) were comparable with that in Beijing in winter (~3 ppbv h−1)44, while they were lower than that in Beijing in summer (10.7 ppbv h−1)40. During the observation, alkenes were the dominant contributors (53.5 ± 14.5%) to the PO3, followed by oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs, 20.1 ± 11.8%), aromatics (14.1 ± 4.7%) and alkanes (11.3 ± 3.7%). Similarly, alkenes accounted for 64.7 ± 8.7% of the total PO3 during CNY, followed by alkanes (12.5 ± 3.5%), aromatics (11.4 ± 2.6%), and OVOCs (10.1 ± 2.9%). The relative contribution of alkenes and aromatics to O3 formation increased around 4.9 and 3.1 times, respectively, during CNY when compared with before and after CNY periods. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, alkenes had the highest RIR value (0.43) during CNY, followed by aromatics (0.10), and OVOCs (0.08). A previous study found that OVOCs play an important role in ROx (ROx = OH + HO2 + RO2) formation (22–44%), subsequently, affecting the O3 production rate46. Thus, the RIR value of OVOCs was lower than that of alkenes and aromatics, but higher than that of alkanes (0.06) during CNY, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9a. In terms of a single VOC compound, ethene, propene, toluene, and xylene showed high RIR values (Supplementary Fig. 9b–d). These four compounds accounted for 46.6 ± 7.1% of PO3 during CNY and 38.7 ± 10.1% of PO3 during the whole observation period. Thus, the O3 pollution event during CNY should be related to the increase in highly reactive VOCs. It should be noted that the peak values of PO3 usually appeared at around 11:00 a.m. This can be explained by the promotion effect of HONO on O3 formation because the photolysis of HONO is an important source of OH radicals in winter47. This is also supported by the maximal photolysis rate of HONO that appeared at 10:00 a.m. as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

The reaction between NO2 and OH was the major contributor to O3 destruction, which contributed 66.2% of the total DO3 during the whole observation period, followed by the photolysis of O3 (27.8%). These values are different from those summertime values reported in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Chengdu, and Lanzhou, e.g., photolysis of O3 and the reaction between NO2 and OH contributing 45.0–72.4% and 11.8–19.2% to the DO3, respectively48. This can be ascribed to different emission patterns of NOx and solar irradiation in different seasons. These results also suggest that the reduction of NOx concentrations during CNY (Fig. 1d) should also indirectly promote the accumulation of O3 by reducing the destruction of O3.

Source apportionment of VOCs and O3 production

To identify the sources of anthropogenic VOCs connecting with O3 pollution during CNY, source apportionment of the observed VOCs was performed using the PMF model. The source profiles are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11a, and the details about source identification are described in Supplementary Discussion 1. Briefly, six types of VOC sources were identified, including biomass burning mixed with fireworks, industrial combustion, cooking, vehicle exhaust, solvent use, and pharmaceutical process exhaust. Figure 4a shows the time series of each source’s contribution to VOCs. As shown in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 11, the order of importance for the sources was industrial combustion (29.4–41.2%), solvent use (13.8–25.4%), biomass burning/fireworks (14.2–16.7%), cooking (13.3–19.5%), vehicle exhaust (8.8–10.8%), and pharmaceutical exhaust (1.7–6.3%).

For comparison, summertime VOC observations were also performed at the same observation site from June 24 to July 27, 2021 (Supplementary Fig. 12). Besides these six sources of VOCs in winter, a biogenic source characterized by high loading of isoprene was also identified in summer. The relative contributions of these sources in summer are in the following order, vehicle exhaust (26.2%) > industrial combustion (24.0%) > cooking (21.7%) > solvent use (9.2%) > biomass burning (9.0%) > biogenic emissions (8.1%) > pharmaceutical exhaust (1.2%). Thus, the contribution of industrial combustion to the observed VOCs (37.8%, 8.9 ± 5.6 ppbv) was higher in winter than that in the summer, i.e., 24.0% (Supplementary Fig. 12c, 2.3 ± 0.9 ppbv). In addition, it can be seen from Supplementary Table 1 that the contributions of OVOCs and aromatics to the total VOCs in summer (25.6% and 11.1%, respectively) are higher than those in winter (17.9% and 7.3%, respectively), while the contributions of alkenes and alkyne to the total VOCs are lower in summer (6.3% and 4.4%, respectively) than those in winter (13.9% and 9.1%, respectively). These results indicate that the role of highly reactive species such as alkenes and alkyne in O3 formation is visible due to the weak irradiation in winter, while it might be underestimated in summer.

To assess the effect of different sources on O3 production capacity, we calculated PO3 and OFP using the OFPT method and MIR method, respectively. The latest MIR values are used to calculate the OFP49. Figure 4e, f shows the contribution of each VOC source to the O3 production rate according to the OFPT method. The largest source of the O3 production rate was industrial combustion (2.6 ± 2.2 ppbv h−1, 39.9 ± 3.7%) during CNY, followed by vehicle exhaust (1.3 ± 1.3 ppbv h−1, 20.6 ± 3.6%), biomass burning/fireworks (0.9 ± 0.8 ppbv h−1, 14.7 ± 0.6%), solvent use (0.9 ± 0.8 ppbv h−1, 14.3 ± 1.0%), cooking (0.6 ± 0.5 ppbv h−1, 8.6 ± 1.6%), and pharmaceutical exhaust (0.1 ± 0.1 ppbv h−1, 1.9 ± 1.0%). For the MIR method, as shown in Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 11c, industrial combustion contributed to 33.0 ± 14.3 ppbv (40.5 ± 3.7%) of the OFP during CNY, and the second important source contributing to the OFP was vehicle exhaust (14.5 ± 8.8 ppbv, 17.3 ± 2.9%), followed by solvent use (13.6 ± 5.5 ppbv, 17.1 ± 1.1%), biomass burning/fireworks (11.2 ± 5.1 ppbv, 13.7 ± 0.5%), cooking (7.0 ± 3.0 ppbv, 8.8 ± 1.3%), and pharmaceutical exhaust (2.1 ± 1.2 ppbv, 2.6 ± 1.0%). As shown in Fig. 4b, f, VOCs and OFPs had similar daily variation patterns, e.g., low values presenting at noon, because the OFPs were obtained by multiplying the VOC concentration and the MIR coefficient, which is a constant value under the specific condition being most sensitive to VOCs49,50,51. Thus, the OFP calculated with the MIR coefficient cannot reflect the actual atmospheric O3 production in terms of diurnal variations, although the order of the source contribution to O3 formation is similar to that of PO3 (Supplementary Figs. 11c, d or Supplementary Table 2). Meanwhile, the PO3 showed a similar diurnal pattern with O3 concentration in the daytime, but different from that of VOCs or OFP, as shown in Fig. 4d. The source apportionment based on the O3 production rate should be more accurate than that based on the MIR method due to the following reasons. (1) The O3 production rates are calculated based on the observed chemicals and meteorological parameters with a high-time resolution rather than that at fixed values of MIR because the formation of O3 is highly correlated with free radicals in the daytime44,52,53. (2) The mean change rate of measured O3 (dcO3, Measured/dt) and net PO3 (have considered the O3 loss) are comparable during the observation period with the peak values of 4.3 and 5.1 ppbv h−1 at 10 a.m., respectively, and the OFP is obviously different from the actual situation (Supplementary Fig. 13). (3) The PO3 is better to indicate the O3 pollution than the OFP during the whole observation period. For example, similar to the O3 concentrations, high PO3 values only occurred during CNY, while high OFP values appeared in all three periods (Figs. 1 and 4). (4) The PO3 generally shows similar diurnal variation patterns with O3 during the observation period, while the OFP shows opposite variation patterns with O3 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, the PO3 is able to correctly reflect the actual diurnal variations of each source to O3 formation.

It should be noted that the total PO3 during CNY was 3.7 times higher than before and after CNY. Besides being the largest source of the PO3 (2.6 ± 2.2 ppbv h−1) during CNY, industrial combustion showed the biggest increment (4.8 times) regarding the PO3 during CNY when compared with the mean value before and after CNY. This is consistent with the fact that the air masses during CNY were dominantly from the southern and eastern regions in the local and neighboring areas (Fig. 2), featured by intensive industrial emissions. In addition, the RIR values of high reactive species (ethene, propene, toluene, benzene, and xylene) from industrial combustion accounted for 36.5% of the total RIR value during CNY (Supplementary Fig. 14). These results highlight the importance of industrial emissions in O3 formation in Shijiazhuang, and highly reactive species play an important role under the conditions of weak irradiation and low temperature in winter. The different emission reduction scenarios of industrial sources were also further studied as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. It can be seen that an 80-100% reduction of industrial emissions during CNY is needed to return to the O3 levels before CNY, which highlights the importance of industry in the observed O3 pollution event. Meanwhile, the PO3 attributed to vehicle exhaust and biomass burning/fireworks with large absolute values (1.3 and 0.9 ppbv h−1) also showed obvious increases (3.7–3.8 times) during CNY. Thus, attention should also be paid to these local sources of O3 pollution.

Although the VOC concentrations in summer (Supplementary Fig. 12d) were lower than that in winter, the O3 production rates in summer (13.1 ± 10.0 ppbv h−1) were larger than that in winter (2.9 ± 3.8 ppbv h−1) due to the stronger solar radiation. Meanwhile, the emission sources of VOCs varied obviously between winter and summer. Thus, the dominant source of O3 also changed obviously. For example, the summertime sources of O3 follows the order of: vehicle exhaust (3.3 ± 2.7 ppbv h−1, 25.0 ± 7.7%) > biogenic (2.7 ± 2.7 ppbv h−1, 20.4 ± 18.6%) > industrial combustion (2.4 ± 1.9 ppbv h−1, 18.4 ± 3.7%) > cooking (1.6 ± 1.3 ppbv h−1, 11.9 ± 3.6%) > solvent use (1.5 ± 1.4 ppbv h−1, 11.8 ± 8.2%) > biomass burning (1.3 ± 1.1 ppbv h−1, 10.3 ± 3.6%) > pharmaceutical exhaust (0.3 ± 0.3 ppbv h−1, 2.3 ± 1.3%). In particular, biogenic VOCs only contributed 8.1% to the total VOCs in summer, while it was the second largest source of the PO3. Industrial combustion, as the observed largest O3 source in winter, became the third source of O3 in summer. In addition, to understand the influence of the components of VOCs on O3 production, a cross-simulation of meteorological conditions was performed. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, the PO3 of industrial combustion increased from 2.6 to 4.1 ppbv h−1 when using summer meteorological conditions during CNY. The virtual PO3 (4.1 ± 3.6 ppbv h−1) is even higher than the PO3 in summer (2.4 ± 1.9 ppbv h−1). The relative contribution of alkenes to PO3 in winter (52.8%) was also higher than that in summer (43.1%) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. These results highlight the highly reactive VOCs from industrial combustion in wintertime O3 photochemistry, while they might be overlooked in summer due to chemical loss.

Discussion

Although the solar radiation was much weaker in wintertime compared to that in summer, wintertime O3 pollution events still occurred in SJZ during our observations. The weak solar radiation facilitates the measurement of highly reactive VOCs. The high RIRs and concentrations of alkenes highlight their importance to O3 formation in winter. In summer, the contribution of these highly reactive species might be underestimated due to photochemical loss. The potential source contribution function (PSCF) results showed the vital role of photochemistry in the observed O3 pollution event. What’s more, O3 pollution during CNY was strongly affected by the changes in weather systems, e.g., the abnormal weakening of the West Pacific subtropical high-pressure system in the southern regions and the temporary appearance of the cut-off low-pressure system in the northern regions of the observation site, which provided favorable conditions for the accumulation and reaction of pollution during CNY. Further analysis in combination with the trajectories of air masses reveals that the levels of VOCs and O3 were well correlated with the ratio of short-ranged trajectories from the southern and eastern regions, implying that local and neighboring emissions contributed to the occurrence of O3 pollution events during CNY. Highly reactive species such as ethylene, propene, toluene, and xylene with high RIR values positively correlated with O3 production during CNY.

To accurately quantify the contribution of different VOC species to ozone production, the OPFT method was developed by tracing the O3 production rate in different generations of VOC oxidation in the OBM, which paves the way for source apportionment of the O3 production rate. The OPFT method reflects the dynamic O3 production under atmospheric conditions at an observational site unlike the O3 source apportionment method based on the MIR values at a fixed atmospheric scenario. In addition, the OPFT method does not interrupt the ratio of VOCs to NOx, which is a problem for the O3 production rate source apportionment based on the RORE or RIR method35, during box model simulations. Thus, the OPFT provides more refined and accurate information on O3 sources when compared with these previous studies. Our results also confirmed that the sequence of O3 source contribution based on the OFPT method is credible when compared with that based on the MIR method if O3 production is in a VOC-limited regime. Moreover, the source apportionment of the PO3 based on the OFPT method could capture not only the diurnal variations of O3 formation but also the long-term time series of O3 pollution in the ambient environment.

With the aid of the developed OFPT approach, the wintertime O3 pollution event was analyzed in detail. The OFPT results found that the increased O3 concentrations during CNY could be ascribed to enhanced O3 production related to industrial combustion, vehicle exhaust, and biomass burning/fireworks, from which highly reactive VOCs were emitted during the CNY. A comparison with the summer results further confirms that highly reactive VOCs were visible in winter due to the lower radiation. It should be pointed out that the OFPT method in this study does not account for vertical or horizontal transport because it is based on a box model. A combination with a 3D air quality model should provide a more comprehensive understanding of O3 pollution in the future.

Methods

Field measurements

The sampling site (Hebei Atmospheric Super Station, 38.03°N, 114.61°N) is located on the rooftop of the main building of Shijiazhuang University, around 25 meters from the ground and around 250 m from Zhujiang Road in SJZ. The observations were carried out from February 2 to 24, 2021, covering before (February 2, 2021, to February 9, 2021), during (February 10, 2021, to February 14, 2021), after CNY (February 15, 2021, to February 24, 2021), and from June 24 to July 27, 2021. The instruments used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. Briefly, the concentrations of VOCs (82 species) were measured with a Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Flame Ionization Detection (GC-MS/FID, EXPEC2000-MS). Trace gases, including NOx, SO2, CO, and O3, were measured with the corresponding analyzer (Thermo Scientific, 42i, 43i, 48i, and 49i). HONO was measured with a Monitoring AeRrosols and Gases in Ambient Air (MARGA, ADI 2080). PM2.5 was measured with a Beta Attenuation Mass Monitor (BAM-1020, Met One Instruments). Meanwhile, meteorological conditions, including temperature, pressure, relative humidity, wind speed, and direction, were monitored using a weather station (WXT 520, Vaisala). More information about the instruments and data quality can be seen in Supplementary Note 1.

Ozone formation path tracing approach (OFPT)

O3 formation was calculated using the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM, v3.3.1, http://mcm.leeds.ac.uk/MCM/). Simulations were performed with the Framework for 0-D version Atmosphere Modeling (F0AM) software package54,55, and constrained by meteorological parameters (T, RH, P), air pollutants (VOCs, NOx, CO, CH4, HONO, SO2), photolysis frequencies (J values). The J values were calculated by the National Center for Atmospheric Research tropospheric ultraviolet and visible (TUV) transfer model (http://www.acd.ucar.edu/TUV), which considers the influence of aerosols and O3, and further corrected according to Eq. 1 to account for the effect of clouds.

Where Jcorrected and JTUV represent the corrected and calculated values of photolysis rate, respectively; SRcloud and SRclear represent the downward solar radiation under cloudy and clear conditions, respectively.

Seventy-two VOC species were selected as OBM inputs (Supplementary Table 5), which accounted for 96.3 ± 2.5% of the total VOC concentrations during the observation period. The PO3 attributed to each species was extracted during OBM simulations using the model’s built-in ExtractRates function. Each step of the simulation is set to link. The PO3 was calculated according to Eq. 2, in terms of the oxidation rate of NO to NO2 by peroxyl radicals (RO2 and HO2). The branching reaction to form RONO2 does not affect the PO3 calculations because it is not traced in the OBM. The destruction rate of O3 (DO3) was calculated according to Eq. 3, in which photolysis of O3 (represented by O1D loss to H2O) and the reactions of O3 with OH, HO2, and alkenes are accounted for40,56. In addition, the reaction between NO2 and OH leads to a net loss of O3 in the daytime, thus it is also considered in Eq. 356.

where ki means the corresponding reaction rate; [i] is the concentration of the species i.

Figure 5 shows the workflow of the OFPT method to obtain the PO3 of each VOC. Briefly, for a VOCj, RO2, and HO2 are searched in all the first-generation products after the reactions are initialized by oxidants (OH, NO3, and O3). If RO2 or HO2 is found, the corresponding reaction rates of HO2/RO2 with NO are recorded. Subsequently, all the first-generation products will further react with oxidants. RO2 and HO2 will be searched in all second-generation products again. If RO2 or HO2 is present, a constraint factor needs to be determined by performing a source-sink analysis of its precursors. The cause is that the traced RO2 or HO2 can be generated from both the first-generation products of the VOCj and other VOCs as well as their products. Then, the factor is used to constrain the reaction rate of the searched RO2 or HO2 with NO. The third-generation reactions are treated in the same way. The reaction rates for the fourth-generation products are close to zero, thus we only account for three generations of RO2 or HO2. In addition, considering that not all RO2 and HO2 radicals eventually generate O3 due to homogeneous or non-homogeneous losses57, the PO3, HO2 and PO3, RO2 obtained from the source-sink equilibrium of O3 are used to constrain the PO3, HO2 and PO3, RO2 from the VOCj, respectively. Moreover, besides oxidants, photolysis is also considered in the OFTP method.

The flow of the OFPT approach explains the calculation process of the contribution of different VOCs to O3 production. The steps in the blue box are calculated using OBM, the steps in the orange box are calculated using PMF, and the step in the green box is calculated using Eq. 4.

VOC source apportionments were calculated by the PMF model (US EPA 5.0). In this study, forty-two species were selected for PMF analysis according to the principles as shown in Supplementary Note 2. The selected VOCs accounted for 94.3 ± 6.9% of the total observed VOC concentrations with an R2 of 0.7, and 82.7 ± 11.9% of the total PO3 during the observation period. More information about PMF model setup and validation can be seen in Supplementary Note 2. A six-factor solution for wintertime VOCs was identified in this study. The contribution of each VOC source to the PO3 at a given time was further calculated by multiplying the fraction of the VOC attributed to a source and its corresponding PO3 traced in the OBM, i.e.,

where SPO3,i is the source contribution of the ith VOC source including n VOC species to O3 production rate at a given time (ppbv h−1); FVOCj,i is the relative contribution of a VOCj to the ith VOC source (%), and PO3, VOCj is the O3 production rate of a VOCj at a given time (ppbv h−1) according to the corresponding product rate of RO2 and HO2 produced from the VOCj.

Empirical kinetic modeling approach and RIR calculation

The EKMA is used to describe the nonlinear relationship between O3 and its precursors NOx and VOCs44. To assess the O3 formation regime, we adopted the OBM to simulate O3 concentration isodepth by varying VOCs and NOx concentrations from 10% to 200% of their mean values during the observation period, while taking the mean values of all other inputs. O3 isopleths were plotted using the averaged MDA8 O3 concentrations. According to a previous study, O3 formation is promoted by HONO, which is an important source of OH radicals58. Thus, HONO was accounted for in the model simulations in our study.

To identify highly reactive species, the RIR method was used to evaluate the sensitivity of different precursors to O3 production59. Briefly, we changed the model input for a target precursor to a certain extent and obtained the correspondingly relative changes of PO3 compared to that of the target species, i.e.,

where c(X) and Δc(X) are the measured concentration and the concentration changes of a precursor X (ppbv), respectively; PO3 and ΔPO3 represent the simulated PO3 in the base scenario and the changes of PO3 resulting from the concentration changes of the precursor. In this study, a relative change of 20% was used as the same as that in a previous study52. The O3 concentrations were calculated in the daytime (8:00–18:00 local time).

Potential source contribution function analysis

The PSCF analysis was performed to understand the possible spatial distribution of the emission sources, by which the air mass transport trajectories at the observed site are calculated60. The 24 h backward trajectories of air mass were calculated with a 1-h temporal resolution from a global database using MeteoInfo software61. The area was divided into 0.5° × 0.5° grid to study VOCs and O3 potential sources. Furthermore, a cluster analysis method was also performed to study the variation of the air mass trajectories during the observation period.

Data availability

The data of air mass backward trajectories are available at ftp://arlftp.arlhq.noaa.gov/. The data of geopotential height and the wind is available at http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/. Solar radiation (SR) was obtained from Copernicus Services (www.copernicus.eu/en). All additional data to perform the analyses are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (liuyc@buct.edu.cn).

Code availability

All additional codes needed to perform the analyses are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (liuyc@buct.edu.cn).

References

Chossière, G. P. et al. Air pollution impacts of COVID-19 related containment measures. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe1178 (2021).

Nair, M., Bherwani, H., Mirza, S., Anjum, S. & Kumar, R. Valuing burden of premature mortality attributable to air pollution in major million-plus non-attainment cities of India. Sci. Rep. 11, 22771 (2021).

Zhang, N.-N., Ma, F., Qin, C.-B. & Li, Y.-F. Spatiotemporal trends in PM2.5 levels from 2013 to 2017 and regional demarcations for joint prevention and control of atmospheric pollution in China. Chemosphere 210, 1176–1184 (2018).

Dai, H. et al. Co-occurrence of ozone and PM2.5 pollution in the Yangtze River Delta over 2013–2019: Spatiotemporal distribution and meteorological conditions. Atmos. Res. 249, 105363 (2021).

Monks, P. S. et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 8889–8973 (2015).

Xiong, C. et al. Component characteristics and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds during summer and winter in downtown Chengdu, southwest China. Atmos. Environ. 258, 118485 (2021).

Seco, R. et al. Contrasting winter and summer VOC mixing ratios at a forest site in the Western Mediterranean Basin: the effect of local biogenic emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 13161–13179 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Characteristics and source apportionment of VOCs in a city with complex pollution in China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 2196–2210 (2020).

Wu, S. et al. Vertical evolution of boundary layer volatile organic compounds in summer over the North China Plain and the differences with winter. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1165–1176 (2021).

Edwards, P. M. et al. High winter ozone pollution from carbonyl photolysis in an oil and gas basin. Nature 514, 351–354 (2014).

Ivatt, P. D., Evans, M. J. & Lewis, A. C. Suppression of surface ozone by an aerosol-inhibited photochemical ozone regime. Nat. Geosci. 15, 536–540 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Ozone pollution in China: a review of concentrations, meteorological influences, chemical precursors, and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 575, 1582–1596 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Composition and reactivity of volatile organic compounds in the South Coast Air Basin and San Joaquin Valley of California. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 10937–10954 (2022).

Zou, Y. et al. Characterization and ozone formation potential (OFP) of non-methane hydrocarbons under the condition of chemical loss in Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. 262, 118630 (2021).

Zhan, J. et al. Ozone and SOA formation potential based on photochemical loss of VOCs during the Beijing summer. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117444 (2021).

Min, S., Bin, W., Sihua, L., Bin, Y. & Ming, W. Effects of Beijing Olympics control measures on reducing reactive hydrocarbon species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 514–519 (2011).

Wang, Z. et al. Implications for ozone control by understanding the survivor bias in observed ozone-volatile organic compounds system. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 39 (2022).

Li, K. et al. Ozone pollution in the North China Plain spreading into the late-winter haze season. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2015797118 (2021).

Huang, R.-J. et al. Primary emissions versus secondary formation of fine particulate matter in the most polluted city (Shijiazhuang) in North China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 2283–2298 (2019).

Guan, Y. et al. Temporal variations and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds at an urban site in Shijiazhuang, China. J. Environ. Sci. 97, 25–34 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Heavy ozone pollution episodes in urban Beijing during the early summertime from 2014 to 2017: implications for control strategy. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117162 (2021).

Zhan, J. et al. Ozone formation sensitivity study using machine learning coupled with the reactivity of volatile organic compound species. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 1511–1520 (2022).

Liu, H., Zhang, M. & Han, X. A review of surface ozone source apportionment in China. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 13, 470–484 (2020).

Zheng, J., Zhong, L., Wang, T., Louie, P. K. K. & Li, Z. Ground-level ozone in the Pearl River Delta region: analysis of data from a recently established regional air quality monitoring network. Atmos. Environ. 44, 814–823 (2010).

Liu, H. et al. A paradox for air pollution controlling in China revealed by “APEC Blue” and “Parade Blue”. Sci. Rep. 6, 34408 (2016).

Song, S.-K. et al. Source apportionment of VOCs and their impact on air quality and health in the megacity of Seoul. Environ. Pollut. 247, 763–774 (2019).

Wang, P., Chen, Y., Hu, J., Zhang, H. & Ying, Q. Source apportionment of summertime ozone in China using a source-oriented chemical transport model. Atmos. Environ. 211, 79–90 (2019).

Russell, A. & Dennis, R. NARSTO critical review of photochemical models and modeling. Atmos. Environ. 34, 2283–2324 (2000).

Vestenius, M. et al. Assessing volatile organic compound sources in a boreal forest using positive matrix factorization (PMF). Atmos. Environ. 259, 118503 (2021).

Jain, V. et al. Seasonal variability and source apportionment of non-methane VOCs using PTR-TOF-MS measurements in Delhi, India. Atmos. Environ. 283, 119163 (2022).

Zheng, H. et al. Monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from an oil and gas station in northwest China for 1 year. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 4567–4595 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Characteristics of one-year observation of VOCs, NOx, and O3 at an urban site in Wuhan, China. J. Environ. Sci. 79, 297–310 (2019).

Shen, H. et al. Novel method for ozone isopleth construction and diagnosis for the ozone control strategy of Chinese cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15625–15636 (2021).

Wang, W., van der, A. R., Ding, J., van Weele, M. & Cheng, T. Spatial and temporal changes of the ozone sensitivity in China based on satellite and ground-based observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 7253–7269 (2021).

Ling, Z. H. & Guo, H. Contribution of VOC sources to photochemical ozone formation and its control policy implication in Hong Kong. Environ. Sci. Policy 38, 180–191 (2014).

Cao, J.-J. et al. Black carbon relationships with emissions and meteorology in Xi’an, China. Atmos. Res. 94, 194–202 (2009).

Wang, B. et al. Variation of ambient non-methane hydrocarbons in Beijing city in summer 2008. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 5911–5923 (2010).

Lu, X. et al. Exploring 2016–2017 surface ozone pollution over China: source contributions and meteorological influences. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 8339–8361 (2019).

Yue, T. et al. Emission characteristics of NOx, CO, NH3 and VOCs from gas-fired industrial boilers based on field measurements in Beijing city, China. Atmos. Environ. 184, 1–8 (2018).

Ma, W. et al. Influence of photochemical loss of volatile organic compounds on understanding ozone formation mechanism. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 4841–4851 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Yang, H., Li, R. & Yu, Q. Seasonal variation and potential source regions of PM2.5-bound PAHs in the megacity Beijing, China: Impact of regional transport. Environ. Pollut. 231, 329–338 (2017).

Zhao, W. et al. Evolution of boundary layer ozone in Shijiazhuang, a suburban site on the North China Plain. J. Environ. Sci. 83, 152–160 (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Quantitation study on VOC emissions and their reduction potential for coking industry in China: based on in-situ measurements on treated and untreated plants. Sci. Total Environ. 836, 155466 (2022).

Tan, Z. et al. Wintertime photochemistry in Beijing: observations of ROx radical concentrations in the North China Plain during the BEST-ONE campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 12391–12411 (2018).

Hamilton, J. F. et al. Key role of NO3 radicals in the production of isoprene nitrates and nitrooxyorganosulfates in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 842–853 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Direct observations indicate photodegradable oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) as larger contributors to radicals and ozone production in the atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 4117–4128 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. The promotion effect of nitrous acid on aerosol formation in wintertime in Beijing: the possible contribution of traffic-related emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 13023–13040 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Photochemical ozone pollution in five Chinese megacities in summer 2018. Sci. Total Environ. 801, 149603 (2021).

Venecek, M. A., Carter, W. P. L. & Kleeman, M. J. Updating the SAPRC Maximum Incremental Reactivity (MIR) scale for the United States from 1988 to 2010. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 68, 1301–1316 (2018).

Carter, W. P. L. Development of ozone reactivity scales for volatile organic compounds. Air Waste 44, 881–899 (1994).

Carter, W. P. L. Computer modeling of environmental chamber measurements of maximum incremental reactivities of volatile organic compounds. Atmos. Environ. 29, 2513–2527 (1995).

Tan, Z. et al. Exploring ozone pollution in Chengdu, southwestern China: a case study from radical chemistry to O3-VOC-NOx sensitivity. Sci. Total Environ. 636, 775–786 (2018).

Ma, X. et al. Winter photochemistry in Beijing: observation and model simulation of OH and HO2 radicals at an urban site. Sci. Total Environ. 685, 85–95 (2019).

Saunders, S. M., Jenkin, M. E., Derwent, R. G. & Pilling, M. J. Protocol for the development of the Master Chemical Mechanism, MCM v3 (Part A): tropospheric degradation of non-aromatic volatile organic compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 3, 161–180 (2003).

Wolfe, G. M., Marvin, M. R., Roberts, S. J., Travis, K. R. & Liao, J. The framework for 0-D atmospheric modeling (F0AM) v3.1. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3309–3319 (2016).

Tan, Z. et al. Daytime atmospheric oxidation capacity in four Chinese megacities during the photochemically polluted season: a case study based on box model simulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 3493–3513 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Potential factors contributing to ozone production in AQUAS–Kyoto campaign in summer 2020: natural source-related missing OH reactivity and heterogeneous HO2/RO2 loss. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 12926–12936 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Amplified role of potential HONO sources in O3 formation in North China Plain during autumn haze aggravating processes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3275–3302 (2022).

Cardelino, C. A. & Chameides, W. L. An observation-based model for analyzing ozone precursor relationships in the urban atmosphere. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 45, 161–180 (1995).

Liu, Y. et al. Evolution and variations of atmospheric VOCs and O3 photochemistry during a summer O3 event in a county-level city, Southern China. Atmos. Environ. 272, 118942 (2022).

Wang, Y. Q., Zhang, X. Y. & Draxler, R. R. TrajStat: GIS-based software that uses various trajectory statistical analysis methods to identify potential sources from long-term air pollution measurement data. Environ. Model. Softw. 24, 938–939 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the specific research fund of The Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (YSPTZX202205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92044301), the Hebei Technological Innovation Center for Volatile Organic Compounds Detection and Treatment in Chemical Industry (ZXJJ20210403), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (8232041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. contributed to the methodology, data curation, software, analysis and writing of the original draft; W.M. contributed to the methodology; Y.L. and X.B. contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, data curation, reviewing and editing the text, supervision, and funding acquisition; B.S., Z.W., H.X., B.C., H.H., and T.J. provided useful advice and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41612_2023_366_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information for The contribution of industrial emissions to ozone pollution: Identified using ozone formation path tracing approach

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, J., Ma, W., Song, B. et al. The contribution of industrial emissions to ozone pollution: identified using ozone formation path tracing approach. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00366-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00366-7

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing solvent extraction methods for activated carbon-based passive samplers in atmospheric volatile organic compound analysis: minimizing analytical interferences from pretreatment solvents and ensuring quantitative reliability

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2025)

-

Assessing Spatiotemporal Characteristics, Health Impacts and Related Economic Losses of PM2.5, PM10 and O3 in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region from 2015 to 2020

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)

-

Effects of ozone pollution on crops and human health: evidence from the “2 + 36” cities of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and surrounding regions, China

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2025)

-

Population exposure to multiple air pollutants and its compound episodes in Europe

Nature Communications (2024)