Abstract

Conventionally, the threat of tropical cyclones (TCs) is often described by TC intensity. However, the damage caused by TCs is also strongly related to our forecasting ability, which is usually low for TCs with high intensification rates. Here, we challenge this intensity-only criterion and propose a concept of TC potential threat (PT) for the western North Pacific TCs by jointly clustering the TC lifetime maximum intensity and intensification rate. We show that TCs can be separated via an objective algorithm, and approximately 10% of all TCs pose a great PT and feature high forecast errors. Furthermore, the annual number of TCs with high PT has increased by 22% per decade over the past 41 years, and this trend is attributed to the rise in subsurface ocean temperatures. Our study provides a perspective on the TC threat and reveals its increase due to global warming and internal climate variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nearly one-third of global tropical cyclones (TCs) originate in the western North Pacific (WNP) basin1, resulting in some of the most destructive natural disasters for the densely populated coastal regions of East Asia2,3,4. Although in many circumstances, several metrics are considered to describe the threat posed by a TC, including its precipitation5, minimum sea-level pressure6, outer size7,8, and storm surge9, its intensity, measured as the maximum sustained surface wind, is possibly the most widely used metric. However, the damage and destruction caused by TCs are not only influenced by their intensity and other metrics but also by early warning and prevention systems related to the prediction and forecasting of TCs. Therefore, improving the forecasting of TCs is essential for minimizing TC-related damage. Although the prediction of TC tracks has steadily improved over the past decades, the forecasting of TC intensity has only shown slow progress10,11,12. This delay is essential because current forecast models struggle to capture the synoptic and internal processes of TCs with high intensification rates (IRs)10,13,14. Thus, to investigate and measure the potential threat (PT) of TCs, it is necessary to consider both TC intensity and IR.

While the concept of PT can be proposed based on both the intensity and IR of a TC, one may reasonably ask how to quantify the combination of both characteristics. Within this context, we first separated the TCs by jointly clustering TC intensity and IR, allowing for the objective categorization of different levels of PT. Similar to Li et al.15, we used an objective clustering method based on the K-means algorithm. Similar algorithms have been used widely in TC research. For instance, joint clustering analysis has been utilized to group western North Pacific and North Atlantic TC tracks based on their locations of genesis and subsequent tracks16,17.

Following the selection of TCs based on clustering, we analyzed long-term fluctuation in the PT of TCs and related environmental conditions. Recently, an increase in the number of major TCs has been observed and projected globally18,19. In addition, recorded increases in TC activity and IRs in coastal regions indicate a further increase in TC-related damage20,21,22,23. The possible slowing down in the decay of TCs in some basins might also cause additional hazards24,25,26. Favorable ambient atmospheric and oceanic conditions, including high mid-level humidity, low deep VWS, and high ocean temperature, are typically required for TC development14,27,28,29. Although long-term variations in these variables and their impact on WNP TC activity have been reported and investigated22,30,31,32,33, their influence on the PT of TCs remains unclear. Against this background, we used composite analysis to investigate the environmental factors associated with various PT levels.

In this study, the WNP TCs were clustered based on the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) dataset34 from 1980 to 2020, as the TC measurements obtained during this period are reliable owing to the wide use of satellite observations and post-season analysis35,36. The subsequent analyses were mainly based on the data measured by the Joint Typhoon Warming Center (JTWC), while observations from the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), Hong Kong Observatory (HKO), and Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) were used for comparison. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) prediction error was analyzed using the THORPEX Interactive Grand Global Ensemble (TIGGE) dataset. In addition, we examined the trends in PT and the impact of related environmental factors. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the concept of potential TC threats and to identify related dominant environmental conditions.

Results

Concept and features of PT

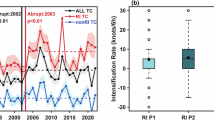

We defined the concept of TC PT using clustering. A total of 1073 TCs were clustered into four groups with cluster sizes of 114 (Group A), 250 (Group B), 284 (Group C), and 425 (Group D) (Fig. 1). The clustering configuration is described in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Two groups (Groups A and B, hereafter severe TCs) were clearly separated from the remaining TCs. These severe TCs had an LMI of 85 kt or greater (Fig. 1a) and thus were at least Category 2 TCs according to the Saffir-Simpson scale (\(\ge\)83 kt). However, although the TCs had similar average LMI values (131.1 and 125.0 kt for Groups A and B, respectively), TCs in Group A were more difficult to predict owing to their higher intensity change (7.5 and 4.7 kt/24 h for A and B, respectively, p < 0.01; Fig. 1b). In addition, all TCs in Group A intensified by at least 30 kt within 24 h before reaching LMI, while only 24% (59/250) of Group B TCs underwent rapid intensification (RI) before reaching LMI (Fig. 1c). As the prediction of RI is arguably the most challenging obstacle in TC intensity forecasts, TCs in Group A are likely to pose a greater threat than those in Group B. The lifetime maximum IR (LMIR) is another metric for investigating TC intensification37. Notably, our results indicate a significant difference in the LMIR between the two groups (60.0 and 41.3 kt/24 h for A and B, respectively, p < 0.01; Fig. 1d), although this metric was not explicitly included in the clustering.

These features include the distribution of a lifetime maximum intensity (LMI, kt), b average intensity change within 24 h (\(\bar{\triangle {\rm{V}}}\), kt/24 h), c intensification change within 24 h before LMI (\(\triangle {\rm{V}}\)24, kt/24 h), and d lifetime maximum intensification rate (LMIR, kt/24 h). The results are based on best-track data from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).

The locations of Group A and B TCs were then compared (Supplementary Fig. 2). Generally, Group A tends to occur at lower latitudes and further to the west than Group B. The average genesis location was 10.8°N, 145.2°E and 12.1°N, 156.0°E for Groups A and B (p = 0.02 for latitude; p < 0.01 for longitude), respectively. While the LMI location was 17.8°N, 132.6°E and 18.9°N, 135.9°E (p = 0.02 for latitude; p = 0.06 for longitude). It is also noteworthy that Group A TCs developed closer to the coast. For instance, 12 out of the 114 TCs in Group A were generated within 400 km of the coast, while only 8 of the 250 TCs in Group B originated in this offshore region. With a higher prediction error associated with the Group-A TCs, as shown below, their enhanced activity in the coastal offshore regions indicates a lower forecast skill and more hazards.

We further examined the robustness of the results by analyzing the best-tract data from other agencies. As done above, the TCs observed by CMA, JMA, and HKO were clustered, resulting in the optimal clustering of 6, 4, and 7 groups, respectively, according to the optimal clustering criteria for each dataset. The LMI and IR were clearly separated for each dataset (Supplementary Figure 3). Consistent with JTWC, TCs in Groups A and B had similar LMI in these datasets, while those in Group A intensified more rapidly, especially for CMA and JMA. Therefore the clustering results are robust among different measurements. However, it should be noted that the intensity was measured differently by each agency, and thus, the values varied substantially.

Our comparison of the short-term forecast further confirmed a significantly higher error for the TCs in Group A (Table 1). The numerical-model-based 24-h forecast error was 23.3 kt for TCs in Group A, which is higher by 3.2 kt than that of the TCs in Group B (p < 0.01). We found similar results for 48-h wind speed and minimum pressure forecasts. In contrast, when only intensity was considered, a similar forecast error was recorded across the different categories. For example, the 48-h error in maximum wind speed was approximately 30 kt for both Category 3 (LMI ≥ 96 kt) and 4 (LMI ≥ 113 kt) TCs. It should also be noted that the TCs in Group A, which were only stronger than Category 2, had a higher prediction error than the Categories 3 and 4 TCs (48-h error in Vmax and 24- and 48-h error in Pmin). These results demonstrate a higher prediction error and threat related to Group A cyclones. Similar results were also found for TC intensity measured by other agencies (Supplementary Tables 1–3).

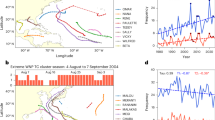

The life cycle of a TC is typically described in terms of several factors, including duration of intensification38 and path length22. Although we did not explicitly consider these factors in clustering, it is evident that path length and intensification duration differed significantly between the TCs in Groups A and B (Fig. 2a, b). Notably, the average intensification time to reach LMI from 20 kt was 105 h for Group A TCs, while the average intensification duration for TCs of Group B was 152 h (p < 0.01). The path length of Group A TCs was also substantially shorter (32%) than that of Group B TCs (1685 km vs. 2460 km, p < 0.01). A shorter path length indicates shorter notice and usually lower predictability. However, when only TC intensity or IR was considered, the differences in duration and path length cannot be observed between intense and weak TCs. For instance, we recorded mean path lengths of 2473 and 2607 km for Category 3 and 4 TCs, respectively.

This includes boxplots of a the intensification duration (h), b path length (103 km), c translation speed (m/s), and d counts of rapid intensification (RI) events for TCs of Groups A and B. The lower and upper ends of the box show the 25th and 75th quartiles, the middle line shows the median and the horizontal bars below and above the box show the 10th and 90th quartiles, respectively.

Intense TCs are typically associated with higher translation speeds39. This is true when only TC intensity is considered. We also found that TCs with an LMI over 96 kt (Category 3) had an average translation speed of 4.5 m/s, while TCs with intensities in Categories 1 and 2 had a translation speed of 4.0 m/s. In contrast, the translation speeds of Group A and B TCs did not differ significantly from the global value (4.2 m/s, Fig. 2c), indicating that translation speed does not significantly affect the PT of TCs when intensity and IR are both considered.

As previously described, RI is a factor of great concern in the forecasting of TCs. In general, TCs undergo an average of 2.1 RI events40, while most weak TCs do not experience any RI events during their life cycle41. Our results indicate that only a few TCs in Groups C and D experienced RI events. In contrast, all TCs in Group A and 235 of 250 TCs in Group B underwent RI. The average number of RI events in Groups A and B were 6.2 and 4.2, respectively. When other thresholds of RI (25, 30, 35, 40 kt/24 h) were selected, significantly more RI events were also detected among Group A than Group B (Supplementary Fig. 4). It should also be noted that all TCs in Group A experienced RI 24 h before reaching LMI, making these TCs even more challenging to predict. In contrast, 60% (151/250) of TCs in Group B underwent RI 24 h prior to LMI (Fig. 2d). When TC intensity estimated by other agencies was used, more RI events were also detected in Group A (Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, TCs in Group A pose a greater threat to the coastal regions of East Asia in terms of operational forecasting.

The potential influence of environmental factors

Environmental conditions, including both atmospheric and oceanic factors, affect the LMI and IR of TCs and can be used as precursors in both weather and seasonal prediction systems27,42,43. In this study, we compared the environmental factors between TCs in Groups A and B based on high-resolution reanalysis data. Only TC events from 1994 to 2020 were analyzed as daily ocean reanalysis data is only available from 1993 onwards when satellite altimetry began to be utilized. For each of the 686 TCs recorded from 1994 to 2020, we averaged atmospheric variables along TC tracks prior to LMI. In contrast, oceanic variables, including sea surface temperature (SST) and TC heat potential (TCHP), which is defined by the ocean heat potential integrated from the depth of the 26 °C isotherm to the surface, were obtained two days before the approach of the TC. A total of 1364 and 3264 maps were obtained for TCs in Groups A and B, respectively. Therefore, through our analysis, we could characterize the influence of environmental factors on TCs.

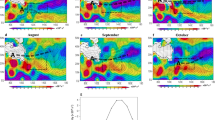

Composite analyses show that the atmospheric environment slightly favors the development of Group A TCs, including a slightly higher mid-level relative humidity (RH) and a lower deep vertical wind shear (VWS) to the north along with a higher VWS to the south of the TC center (Fig. 3a, b). However, these differences were statistically insignificant over most of the 20° by 20° box. In addition, the vorticity and divergence were similar among the groups (Fig. 3c, d). Therefore these atmospheric conditions were not the critical environment underlying the different intensification activity between the two types.

The environmental factors include a 600-hPa relative humidity (RH, %), b 200- and 850-hPa vertical wind shear (VWS, m/s), c 850-hPa relative vorticity (Vort, 10−5 s−1), d 200-hPa divergence (Div, 10−5 s−1), e sea surface temperature (SST, °C), and f tropical cyclone heat potential (TCHP, 107 J m−2) between Groups A and B. Data were obtained from the ERA5 and GLORYS reanalyses for atmospheric and oceanic variables, respectively. The atmospheric factors were averaged 1 day to 0 h prior to TC passage, while the oceanic factors were averaged 5 to 2 days before TC approaching. The unit for the x- and y-axes is degrees. Black dots indicate statistically significant differences at the 99% confidence level based on Student’s t-test. The three circles are placed at radii of 2°, 5°, and 10° from the TC center.

In contrast, oceanic variables, especially subsurface temperature, differed significantly between the two groups (Fig. 3e, f). The pre-storm SST for Group A was 0.3 °C higher than that of Group B (29.3 °C vs. 29.0 °C, respectively). The meridional gradient of SST was also weaker for the TCs of Group A, with differences as high as 0.5 °C in the northern part of the square domain. However, these differences were statistically insignificant over most of the 20° by 20° box. In contrast, the two groups showed significant differences in the subsurface temperature. Specifically, TCs in Group A had a TCHP that was approximately higher by 15 × 107 J m−2 than those in Group B (81.6 vs. 66.6 × 107 J m−2). These differences were significant over the majority of the domain. Notably, the difference in TCHP is in the order of its annual anomalies44. In addition, TCHP was significantly higher in Group B than in Groups C and D over the entire domain (figure not shown). Therefore, the subsurface thermal structure is likely the dominant factor driving the intensification of these severe TCs. Typically, TCs cool the ocean surface by strengthening turbulent mixing and upwelling, which in turn weakens the overlying TCs45. Therefore, a warmer subsurface is more favorable for TC development. Our results correspond to the findings from previous studies, which suggest that subsurface temperature is related to TC intensification in both short-term14 and long-term TC prediction46.

The long-term trend of severe TCs

Long-term variations of different groups of TCs are worth investigating as they pose diverse PT. Consistent with the results of previous studies47, our findings indicate a decrease in the total number of TCs over the past four decades at a rate of 0.9 per decade (p = 0.1), while the number of major TCs (LMI > Category 3) and TCs undergoing RI (RI TCs) remained constant (Fig. 4a). In addition, based on clustering, it is evident that this declining trend is primarily a characteristic of TCs in Groups B, C, and D (Fig. 4b, c), although the trend was only statistically significant for Group D (0.9 per decade, p < 0.05). In contrast, the number of TCs in Group A increased by 0.8 per decade (p < 0.01, Fig. 4b), and the portion of TCs in this group increased by 3.2%/decade (p < 0.01). In addition, a decreasing trend in the average life cycle of major TCs has recently been reported38. Our results indicate that this shortening of the life cycle can be attributed to the increase in Group A TCs and the decrease in Group B TCs, as the life cycle of the former group is significantly shorter than that of the latter. The measurements from other agencies also showed that the annual count of TCs with high PT raised by 0.4–0.6/dec among different datasets, and the trends were statistically significant, indicating a robust increase in the severe TCs (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 6).

We further investigated long-term TCHP trends for the primary TC basin (5–20°N, 120–180°E), as the composite analyses indicated that it had a dominant role. The TCHP has increased by 6.3 × 107 J m−2 per decade over the past four decades (7.3% per decade, p < 0.01, Fig. 4d). Considering the concurrent increase in Group A and decrease in other groups, the crucial role of ocean subsurface temperature in driving long-term variation of the most destructive TCs is evident. Additionally, when only LMI or IR was considered, the annual number of TCs declined or only increased slightly. Therefore, TCs in Group A were in better agreement with the long-term variation in oceanic environmental factors, which are found to be dominant factors influencing TC variation.

TCHP over two other regions was also compared, as suggested by Mei et al.22 (12–30°N, 130–152°E) and Song et al.48 (10–20°N, 120–150°E). The average TCHP generally increased over all three regions, with the two regions to the west of 150°E experiencing a slight decrease after approximately 2005 (Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, TCHP over the primary TC basin defined here (5–20°N, 120–180°E) kept increasing and explains the variations in the TC activity of Group A better.

Both global warming and climate internal variability, including El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), could potentially affect TC activity48,49,50. The influences of these phenomena were also investigated, using Niño3, PDO, AMO indices, and global mean SST between 60°S and 75°N. Here we show that the annual count of TCs in Group A and seasonal-mean TCHP were more closely related to the global SST warming than to the PDO and AMO (Supplementary Fig. 8). The effects of global warming and climate variabilities were further isolated via linear regression30,51. After removing the signal of global SST, the trend of the residual count of TCs in Group A was no longer statistically significant (trend = 0.14/dec, p = 0.58, Supplementary Fig. 9). In contrast, the remaining TC count still increased significantly after removing PDO (trend = 0.77/dec, p < 0.01), Niño3 (trend = 0.76/dec, p < 0.01) or AMO signals (trend = 0.46/dec, p = 0.08). Therefore the increases in TCHP and TC activity are more likely caused by global warming.

Discussion

Improving the forecasting of TC intensity is crucial for reducing TC-related damage. A high IR is usually associated with low prediction skills, which leads to less preparation time and more damage. We, therefore, proposed the new concept of a PT using joint clustering. The TCs with high PT were featured with high intensity, RI, and low forecast skills. We further show that the annual count and ratio of TCs with high PT have increased significantly over the past four decades, which is more consistent with the rise in tropical warming. However, only considering TC intensity or IR does not detect such a rapid increase.

Further, we analyzed environmental factors related to TC intensification by comparing the composites of RH, VWS, vorticity, divergence, and pre-storm oceanic temperatures between the two groups of severe TCs (A and B). Our results showed that the most significant differences existed in TCHP. Therefore, TCHP is closely related to the intensification of TCs and their resulting destruction. In addition, because the depth of the 26 °C isotherm is approximately 80 to 120 m in WNP, monitoring ocean temperature at these levels is of great importance for the prediction of the most destructive TCs. Moreover, we show that significant differences exist in the ocean temperature anomalies (Supplementary Figure 10), but we can not entirely exclude the impact of spatial and seasonal distributions, and more case studies and numerical simulations are required to better understand the underlying mechanism.

Previous studies have indicated that the WNP offers a more favorable oceanic environment for the development of intense TCs22,31,52, but the increase in the number of intense TCs was much slower than predicted47. In contrast, based on the clustering method, our results indicate that TCs with both high intensity and RI increased significantly faster than those with only a high IR. We further attribute this increase to global warming and highlight the importance of subsurface ocean temperature in the tropical western Pacific. This result corresponds with the warming trend in ocean temperatures and highlights the increased risk of TC-related hazards in a warmer climate. However, a period of 41 years could be insufficient to clearly demonstrate long-term trends or provide evidence of global warming53. In addition, a climate regime shift has been reported as occurring around 200054, and the slow-down of global warming from around 2005 to 2015 is also possibly linked with internal climate variability55. The contributions of such events are difficult to quantify based on the statistical analyses in this study. The analyses were limited to this period due to the lack of quality of earlier best-track data. Many studies focused on the period after 1980 when satellite observations became widely available30,38. A bootstrap experiment was further performed, in which the increases in the annual counts of TCs in Group A were calculated using 35, 30, or 25 years randomly sampled from this 41-year period. Substantial increases in annual TC counts within Group A were detected (Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating that the trend was robust. Nevertheless, conducting further investigations using reliable high-resolution numerical simulations or downscaling techniques56 is necessary.

We only considered TC intensity in this study, mainly because its measurements and forecasts were widely available. However, TC destruction was also caused by other metrics, including size, precipitation, and storm surge5,7,8,9. The variations of these metrics are usually independent of intensity7,9,57,58, and further studies are thus warranted. In addition, more clustering models can be examined, and a systematic comparison is required to validate the actual destruction and prediction error of TCs with high PT. Nevertheless, the novel concept of PT can be an important complement to the conventional destruction categories. Finally, within the context of increasing ocean temperatures and the related increase in the PT of TCs, there is a definite need for improved TC forecasting and greater mitigation efforts.

Methods

TC data

TC best-track observations were obtained from the IBTrACS, v4r0034, in which the data for WNP were provided by JTWC. For comparison, the intensity data measured by the CMA, HKO, and JMA were also used. TC intensity was measured as the 1-minute sustained surface wind by JTWC, while it was defined as the 2-, 10-, and 10-min sustained wind by CMA, JMA, and HKO, respectively. To facilitate the comparison of TC intensity estimated by the four agencies, the 2- and 10-minute sustained winds were divided by conversion factors of 0.93 and 0.9659 to convert to the 1-min sustained wind.

We only considered tropical storms (LMI ≥ 34 kt) over the period 1980–2020. In addition, to eliminate the influence of topographic effects and extra-tropical transition, we chose only TC tracks over the ocean and within the range of 0° and 40°N. We only took the records at the standard observational times: 00, 06, 12, and 18 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). A total of 1073 TCs, reaching the tropical storm intensity, were extracted from the JTWC measurement. The mean LMI, average IR, and IR24 were 82.3 kt, 4.2 kt/24 h, and 23.7 kt/24 h, respectively. These values are similar to previous studies60,61. CMA, JMA, and HKO recorded 956, 736, and 903 TCs, respectively.

The IR was calculated as the change in the maximum surface wind speed (Vmax) in 24 h. RI is commonly defined as an increase in the surface maximum wind speed (Vmax) of at least a threshold within 24 h62. The threshold of 30 kt (15.4 m/s), as recommended by Kaplan and DeMaria62, was used as the definition of RI. Other thresholds of 25, 35, 40, and 45 kt were used for comparison.

Environmental variables

We used the atmospheric reanalysis from the ERA5 dataset (the fifth generation of ECMWF reanalysis63) with a resolution of 0.25°. The VWS was calculated as the amplitude of the wind vector difference between the 200- and 850-hPa pressure levels. The mid-level RH, low-level relative vorticity, and upper-level divergence were obtained at 600, 850, and 200 hPa, respectively. The GLORYS daily ocean reanalysis with a resolution of 0.083° provided by the Copernicus Marine Service was used for the case-by-case analysis between 1994 and 2020. The NCEP Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) monthly mean ocean temperature with a resolution of 1° was used for the trend analysis from 1980 to 2020. The influences of global warming and internal climate variability were analyzed using global SST data, PDO, and AMO indices obtained from the Met Office Hadley Centre and National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NCEI, NOAA), respectively. Global ocean warming was estimated using global mean SST between 60°S and 75°N51.

Forecast data

The numerical model forecast by ECMWF was retrieved from TIGGE. We used the 24-h and 48-h forecasts over the period of 2007 to 2020.

Clustering method

We clustered the WNP TCs using the K-means algorithm. This algorithm partitions the samples into subsets while minimizing the variance within each cluster. The input variables were the LMI, average intensity change (\(\bar{\triangle {\rm{V}}}\)) and \(\triangle {\rm{V}}\) within 24 h before reaching LMI (\(\triangle {\rm{V}}\)24). The silhouette and Davies–Bouldin indices were used to estimate the optimal choice of clustering numbers (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Statistical information

In this study, we calculated the trend via linear regression. For the composite and trend analyses, a two-tailed t-test with a p-value of 0.01 was used to test significance, with a null hypothesis of zero correlation.

Removal of the global SST trend and climate indices

Following Dai et al.51 and Kossin et al.30, the influence of a certain index on the long-term trend could be removed via linear regression from the time series T. Let T(n, i) be the number of Group A TCs for year n and X(n) be the climate index X for year n, where n = 1, 2,…, 41 for 1980–2020. The climate indices considered in this study were the global annual mean SST, ENSO, PDO and AMO. Using a linear regression method, we estimated the trend caused by individual or combination of factors X, Tx(n) = bxX(n), where bx is the slope in T(n) = bxX(n) + ε(residual). The residual ε was then analyzed.

Bootstrap experiment

In the bootstrap experiment, 1000 repetitions were performed. In each repetition, we randomly selected 35-, 30-, or 25-year samples from the dataset during the period of 1980–2020 and calculated the trend within the subsample.

Data availability

IBTrACS data were downloaded from the NCEI website (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/international-best-track-archive-for-climate-stewardship-ibtracs/v04r00/access/csv/ibtracs.ALL.list.v04r00.csv), ERA5 data were downloaded from the Climate Data Store (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6), GLORYS and GODAS ocean reanalysis were downloaded from the Copernicus Marine Service (https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/product-detail/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/INFORMATION) and Climate Prediction Center (https://cfs.ncep.noaa.gov/cfs/godas/monthly/), and TIGGE forecast data were downloaded from the Research Data Archive (https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds330.3/#!description). The global SST data with a resolution of 1° were obtained from the Met Office Hadley Centre (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadsst2/), and the PDO index data were downloaded from NCEI, NOAA (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/cmb/ersst/v5/index/ersst.v5.pdo.dat).

Code availability

The source codes for the analysis of this study are available from Yi Li (yli.ouc@gmail.com) upon reasonable request.

References

Balaguru, K., Foltz, G. R., Leung, L. R. & Emanuel, K. A. Global warming-induced upper-ocean freshening and the intensification of super typhoons. Nat. Commun. 7, 13670 (2016).

CMA. Member report. in (ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee 16th Integrated Workshop, 2021).

Elliott, R. J. R., Eric, S. & Sun, P. The local impact of typhoons on economic activity in China: a view from outer space. J. Urban Econ 88, 50–66 (2015).

Peduzzi, P. et al. Global trends in tropical cyclone risk. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 289–294 (2012).

Chen, P., Yu, H., Cheung, K. K. W., Xin, J. & Lu, Y. A potential risk index dataset for landfalling tropical cyclones over the Chinese Mainland (PRITC dataset V1.0). Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1791–1802 (2021).

Klotzbach, P. J. et al. Surface pressure a more skillful predictor of normalized hurricane damage than maximum sustained wind. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E830–E846 (2020).

Li, Y., Tang, Y. & Wang, S. Rapid growth of outer size of tropical cyclones: a new perspective on their destructive potential. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099230 (2022).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. On the relationship between hurricane cost and the integrated wind profile. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 114005 (2016).

Resio, D. T. & Irish, J. L. Tropical cyclone storm surge risk. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 74–84 (2015).

Cangialosi, J. P. et al. Recent progress in tropical cyclone intensity forecasting at the National Hurricane Center. Weather Forecast. 35, 1913–1922 (2020).

Emanuel, K. Will global warming make hurricane forecasting more difficult? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 495–501 (2017).

Landsea, C. W. & Cangialosi, J. P. Have we reached the limits of predictability for tropical cyclone track forecasting? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 2237–2243 (2018).

Courtney, J. B. et al. Operational perspectives on tropical cyclone intensity change part 1: recent advances in intensity guidance. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 8, 123–133 (2019).

Kaplan, J. et al. Evaluating environmental impacts on tropical cyclone rapid intensification predictability utilizing statistical models. Weather Forecast. 30, 1374–1396 (2015).

Li, Y., Tang, Y., Toumi, R. & Wang, S. Revisiting the definition of rapid intensification of tropical cyclones by clustering the initial intensity and inner-core size. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD036870 (2022).

Camargo, S. J., Robertson, A. W., Gaffney, S. J., Smyth, P. & Ghil, M. Cluster analysis of typhoon tracks. Part I: general properties. J. Clim. 20, 3635–3653 (2007).

Guo, X. & Tan, Z.-M. Tropical cyclone fullness: a new concept for interpreting storm intensity: tropical cyclone fullness. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 4324–4331 (2017).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: part I: detection and attribution. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 1987–2007 (2019).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: part II: projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E303–E322 (2020).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514–517 (2021).

Zhao, H., Duan, X., Raga, G. B. & Klotzbach, P. J. Changes in characteristics of rapidly intensifying Western North Pacific tropical cyclones related to climate regime shifts. J. Clim. 31, 8163–8179 (2018).

Mei, W., Xie, S.-P., Primeau, F., McWilliams, J. C. & Pasquero, C. Northwestern Pacific typhoon intensity controlled by changes in ocean temperatures. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500014 (2015).

Zhao, J., Zhan, R. & Wang, Y. Global warming hiatus contributed to the increased occurrence of intense tropical cyclones in the coastal regions along East Asia. Sci. Rep. 8, 6023 (2018).

Li, L. & Chakraborty, P. Slower decay of landfalling hurricanes in a warming world. Nature 587, 230–234 (2020).

Chan, K. T. F., Chan, J. C. L., Zhang, K. & Wu, Y. Uncertainties in tropical cyclone landfall decay. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 93 (2022).

Chan, K. T. F., Zhang, K., Wu, Y. & Chan, J. C. L. Landfalling hurricane track modes and decay. Nature 606, E7–E11 (2022).

Chan, K. T. F., Dong, Z. & Zheng, M. Statistical seasonal forecasting of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 074027 (2021).

Guo, Y.-P. & Tan, Z.-M. Westward migration of tropical cyclone rapid-intensification over the Northwestern Pacific during short duration El Niño. Nat. Commun. 9, 1507 (2018).

Shay, L. K., Goni, G. J. & Black, P. G. Effects of a warm oceanic feature on Hurricane Opal. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1366–1383 (2000).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Camargo, S. J. Past and projected changes in western North Pacific tropical cyclone exposure. J. Clim. 29, 5725–5739 (2016).

Sasaki, H. & Motoi, T. Accelerated Increase in tropical cyclone heat potential in the typhoon rapidly intensifying zone during 1955-2020. SOLA 18, 65–70 (2022).

Lin, I.-I., Wu, C.-C., Pun, I.-F. & Ko, D.-S. Upper-ocean thermal structure and the Western North Pacific Category 5 Typhoons. Part I: Ocean Features and the Category 5 Typhoons’ Intensification. Mon. Weather Rev. 136, 3288–3306 (2008).

Lin, I.-I. & Chan, J. C. L. Recent decrease in typhoon destructive potential and global warming implications. Nat. Commun. 6, 7182 (2015).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): unifying tropical cyclone data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Vecchi, G. A. The poleward migration of the location of tropical cyclone maximum intensity. Nature 509, 349–352 (2014).

Landsea, C. W. & Franklin, J. L. Atlantic hurricane database uncertainty and presentation of a new database format. Mon. Weather Rev. 141, 3576–3592 (2013).

Wu, X. et al. Climatic variation of maximum intensification rate for major tropical cyclones over the Western North Pacific. Atmosphere 12, 494 (2021).

Wang, S., Rashid, T., Throp, H. & Toumi, R. A shortening of the life cycle of major tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088589 (2020).

Mei, W., Pasquero, C. & Primeau, F. The effect of translation speed upon the intensity of tropical cyclones over the tropical ocean: TC translation speed affects intensity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L07801 (2012).

Song, J., Klotzbach, P. J. & Duan, Y. Increasing lifetime maximum intensity of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034002 (2021).

Lee, C.-Y., Tippett, M. K., Sobel, A. H. & Camargo, S. J. Rapid intensification and the bimodal distribution of tropical cyclone intensity. Nat. Commun. 7, 10625 (2016).

DeMaria, M. A simplified dynamical system for tropical cyclone intensity prediction. Mon. Weather Rev. 137, 68–82 (2009).

DeMaria, M. & Kaplan, J. A Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction Scheme (SHIPS) for the Atlantic Basin. Weather Forecast. 9, 209–220 (1994).

Guo, Y. & Tan, Z. Influence of track change on the inconsistent poleward migration of typhoon activity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD036640 (2022).

Schade, L. R. & Emanuel, K. A. The ocean’s effect on the intensity of tropical cyclones: results from a simple coupled atmosphere–ocean model. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 642–651 (1999).

Balaguru, K., Foltz, G. R. & Leung, L. R. Increasing magnitude of hurricane rapid intensification in the Central and Eastern Tropical Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4238–4247 (2018).

Kang, N.-Y. & Elsner, J. B. Influence of global warming on the rapid intensification of western North Pacific tropical cyclones. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 044027 (2019).

Song, J., Duan, Y. & Klotzbach, P. J. Increasing trend in rapid intensification magnitude of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 084043 (2020).

Sun, C. et al. Western tropical Pacific multidecadal variability forced by the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Nat. Commun. 8, 15998 (2017).

Zhao, H. & Wang, C. Interdecadal modulation on the relationship between ENSO and typhoon activity during the late season in the western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 47, 315–328 (2016).

Dai, A., Fyfe, J. C., Xie, S.-P. & Dai, X. Decadal modulation of global surface temperature by internal climate variability. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 555–559 (2015).

Lin, I.-I., Chen, C.-H., Pun, I.-F., Liu, W. T. & Wu, C.-C. Warm ocean anomaly, air sea fluxes, and the rapid intensification of tropical cyclone Nargis (2008): Warm Ocean Anomaly And Cyclone Nargis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L03817 (2009).

Chand, S. S. Declining tropical cyclone frequency under global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 655–661 (2022).

Rodionov, S. N. A sequential algorithm for testing climate regime shifts: algorithm for testing regime shifts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L09204 (2004).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Camargo, S. J. & Wing, A. A. Tropical cyclones in climate models. WIREs Clim. Change 7, 211–237 (2016).

Chavas, D. R. & Lin, N. A model for the complete radial structure of the Tropical Cyclone wind field. Part II: wind field variability. J. Atmos. Sci. 73, 3093–3113 (2016).

Chen, P., Yu, H., Xu, M., Lei, X. & Zeng, F. A simplified index to assess the combined impact of tropical cyclone precipitation and wind on China. Front. Earth Sci. 13, 672–681 (2019).

Lee, T., Leung, C. Y., Kok, M. & Chan, H. The long term variations of tropical cyclone activity in the South China Sea and the vicinity of Hong Kong. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev 1, 277–292 (2012).

Emanuel, K. A statistical analysis of tropical cyclone intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1139–1152 (2000).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. A historical analysis of the mature stage of tropical cyclones: tropical cyclone mature stage. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 2490–2505 (2018).

Kaplan, J. & DeMaria, M. Large-scale characteristics of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic basin. Weather Forecast. 18, 1093–1108 (2003).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 42130409 and 42006036) and Hohai University (grant No. 522020512).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and T.Y. conceived the study. Y.L. analyzed the initial results, and all authors discussed the results. Y.L. completed the draft. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Tang, Y., Li, X. et al. Recent increase in the potential threat of western North Pacific tropical cyclones. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 53 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00379-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00379-2

This article is cited by

-

Sharp Increase in rapid intensification of Arabian Sea tropical cyclones over the past decade

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)