Abstract

Ocean-onto-land droughts (OTLDs)—i.e., droughts originating over the oceans and migrating onto land—are a recently identified phenomenon with severe natural and human impacts. However, the influence of anthropogenic emissions on past and future changes in OTLDs and their underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Here, using precipitation-minus-evaporation deficits to identify global OTLDs, we find OTLDs have intensified due to anthropogenic climate change during the past 60 years. Under a future high-emissions scenario, the OTLDs would become more frequent (+39.68%), persistent (+54.25%), widespread (+448.92%), and severe (+612.78%) globally. Intensified OTLDs are associated with reduced moisture transport driven by subtropical anticyclones in the northern hemisphere and complex circulation patterns in the southern hemisphere. The reduction in moisture transport during OTLDs is mainly caused by the atmospheric thermodynamic responses to human-induced global warming. Our results underscore the importance of improving understanding of this type of drought and adopting climate mitigation measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Droughts on land have severe impacts on water resources, agriculture, ecosystems, and socio-economic sustanability1,2,3,4. Recently, precipitation‐minus‐evaporation (PME) deficits originating over the ocean and migrating onto land have been identified as an essential contributor to droughts on land5. For instance, PME deficits over the northern Atlantic were found to have led to a significant decrease in terrestrial water storage in the southern Tibetan Plateau and northeastern Asia through diminishing moisture transport6,7. These moisture deficits are responsible for a specific newly identified type of drought termed ocean-onto-land drought (OTLD), which is more extensive and intense than land-only droughts (only originating from and developing over land)5. Specifically, the OTLDs were found 435% larger, 30% more intense, 285% grew and 28% intensified faster than land-only droughts during 1981–2018 a global scale. In comparison with land-only droughts, much less is known about how OTLDs have changed in the past and may change in the future. This knowledge gap is of considerable concern given the severe impacts of OTLDs on continental natural and human systems.

One critical concern with respect to droughts is understanding the impacts of anthropogenic climate change on their spatio-temporal evolution. Recent studies have shown that the anthropogenic signal is clearly detected in changes in drought characteristics, such as frequency, duration, and intensity8,9,10,11,12. Anthropogenic emissions have also resulted in droughts with faster onset and more widespread areas13,14,15. Although there is mounting evidence that human-induced global warming intensifies droughts, the question of whether the anthropogenic climate change signal is detectable in changes in OTLDs is still unknown.

The occurrence of OTLDs is associated with diminished moisture transport (quantified by PME deficits) from the ocean. For instance, OTLDs over western North America (WNA) are associated with PME deficits over the eastern Pacific moving toward WNA5. The PME deficits mainly have two physical drivers, i.e., atmospheric thermodynamic and dynamic processes, related to changes in atmospheric humidity and large-scale circulation16,17,18,19,20. Under global warming, projected thermodynamic changes include increases in moisture transport21,22,23 due to the heightened moisture-holding capacity of saturated air (roughly 7%·°C-1, following the Clausius–Clapeyron relation). Dynamic changes include circulation pattern shifts such as poleward shifts of jet streams and storm tracks24,25 that may modulate directions of moisture transport26,27. Thus, in the case of OTLDs, if a key question is understanding whether there is a detectable signal of anthropogenic climate change, and if so, how the underlying physical factors for OTLD-related moisture transport might be affected.

In this study, we identify all OTLDs in the historical simulations (ALL; “Methods”) from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)28 (Supplementary Table 1), and the Shared Socio-economic Pathway 5–8.5 projections (SSP585) derived from Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP)29 of CMIP6, alongside the fifth generation of the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis (ERA5). We analyze changes in OTLD characteristics (frequency, duration, intensity, and areal extent) in the past and future, and conduct quantitative detection and attribution of these changes to anthropogenic emissions. We then explore changes in OTLD-related moisture transport in response to anthropogenic warming, and we disentangle their underlying thermodynamic and dynamic physical drivers. All acronyms are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Results and discussion

Human-induced changes in past and future OTLDs

During 1961–2020, a total of 4516 OTLDs were identified across the globe from 10 CMIP6 models under ALL, with duration of 10.47 ± 0.49 months (mean ± 1 standard deviation), maximum area of 1.65 ± 0.33 × 106 km2, and intensity of 1.55 ± 0.38 × 105 mm. The state-of-the-art reanalysis dataset (ERA5) was used to correct the simulated bias of PME from CMIP6 compared to ERA5, as well as further assess the ability of bias-corrected CMIP6 models to simulate OTLDs. Results suggest that the spatial patterns of these OTLD characteristics are relatively well captured by CMIP6 multi-model ensemble mean (CMIP6-EM) (spatial correlations between ALL and ERA5: 0.65 < r < 0.69; 0.10 < relative error < 0.18; p < 0.001; Fig. 1). This is also the case for most OTLD characteristics across the CMIP6 individual models. High spatial correlations (>0.5; p < 0.001) are found in 58% of all combinations (29 out of 50 combinations, i.e., 5 characteristics × 10 models; Fig. 1c, f, i, l, o). The variances of each OTLD characteristic with small differences (i.e., the variance of each model is less than 1.5 times that of ERA5) between CMIP6 and ERA5 also validate the ability to simulate spatial patterns of OTLD characteristics. After the selection by total magnitude of OTLDs (“Methods”), the resulting 1000 OTLDs (i.e., 100 events × 10 models) account for the top 22% ± 2% of all (ALL: 452 ± 37 OTLDs for the multi-model mean; historical natural simulations (NAT): 449 ± 31) OTLDs from all CMIP6 models.

Maps and Taylor diagrams show the frequency (a–c), duration (d–f), areal extent (g–i), intensity (j–l), and total magnitude (m–o) of OTLDs over the globe (excluding Antarctic, Greenland, and the Sahara Desert) during 1961–2020. Each column shows corresponding characteristics derived from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, CMIP6 multi-model ensemble mean (CMIP6-EM; b, e, h, k, n), and 10 individual CMIP6 models (e, f, i, l, o). The dots in the bottom-left subplots accompanying the maps b, e, h, k, n represent the characteristics of OTLDs in each grid cell between CMIP6-EM and the ERA5 reanalysis dataset. The symbol “RE” indicates the relative error. Above all correlation is at 0.001 significance level. The figure is done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/).

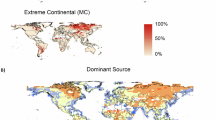

Globally, probability density functions of duration, maximum area, intensity, and total magnitude of OTLDs under ALL show a statistically significant rightward shift relative to NAT (Fig. 2a–d), implying that anthropogenic emissions significantly enhance OTLDs. Spatially, positive anomalies (difference between ALL and NAT divided by ALL during 1961–2020) of OTLD frequency, duration, areal extent, intensity, and total magnitude are found in 70.63%, 64.90%, 67.46%, 73.95%, and 69.52% of the global land surface, respectively (Fig. 2f–j). This indicates that more frequent, persistent, widespread, and severe OTLDs are associated with anthropogenic climate change, especially over the six landfalling OTLD hotspots (i.e., WNA, southern South America (SSA), Europe and northern Africa (EA), southern Africa (SAF), eastern Asia (EAS), and Australia (AU); Fig. 2e). Note that EA is dominated by negative anomalies of these OTLD characteristics when comparing ALL and NAT, which may be attributed to the influence of anthropogenic aerosols (AER) emissions in the historical period (Supplementary Fig. 2). As another site for considerable AER emissions, EAS represents positive anomalies of OTLDs characteristics due to the greater influence of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than that of AER emissions. We find negative (positive) anomalies of OTLD characteristics over 41.99–63.99% (42.47–69.38%) of the EA (EAS) region when comparing the ALL and the GHG simulations, but only over 25.27–44.86% (89.16–98.85%) when comparing the ALL and the AER simulations. This indicates an enhancement effect of GHG on historical OTLDs. As GHG emissions are projected to continuously increase in the future, while AER emissions are likely to decrease, this suggests that there may be a shift from weakening to enhancing OTLDs over EA.

a–d Probability density functions for the duration (a), intensity (b), maximum area (c), and total magnitude (d) of ALL OTLDs (red lines) vs. NAT OTLDs (blue lines); p-values indicate the significance of differences between the distributions based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. e Total frequency of landfalling OTLDs in the ALL scenario (red gradient). f–j Anomalies (difference between ALL and NAT divided by ALL during 1961–2020) in the frequency (f), duration (g), intensity (h), areal extent (i), and total magnitude (j) of OTLDs for the multi-model mean between ALL and NAT. Black dots represent regions with significant differences in OTLD characteristics (p-value < 0.05 based on the student’s t-test). Error bars in the bottom-left subplot (f–j) show the relative anthropogenic index (RAI) estimates and their 90% confidence intervals (CIs; from bootstrapping) of OTLD characteristics for the globe and the six hotspots. The figure is done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/).

We use the relative anthropogenic index (RAI; see “Methods”) to quantify the signal of anthropogenic climate change in the intensification of OTLDs (Fig. 2f, j). Globally, the median (i.e., best estimate) value of RAI for frequency, duration, intensity, areal extent, and total magnitude, and their 90% confidence intervals (CIs) are above zero, suggesting that the signal of anthropogenic climate change is very likely detectable in the global intensification of OTLDs (probability >90%; Fig. 2f–j). This is also the case for most OTLD characteristics across the six hotspots. Specifically, the anthropogenic signal is detectable in 63% of all combinations (19 out of 30 combinations, i.e., 5 characteristics ×6 hotspots).

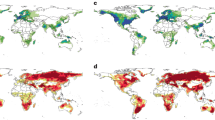

We next assess future changes in OTLDs under SSP585, an extreme emissions scenario (Fig. 3). In comparison with the historical period (1961–2020), the landfall frequency of OTLDs would be projected to increase by 63.13–223.82% in the six hotpots during 2021–2100 (Fig. 3a). The future growth of OTLDs would occur over most (i.e., 64.60–83.36%) of the global land surface (Fig. 3b–f). These findings reveal that an extreme human-induced climate change scenario would result in more frequent (+39.68%), persistent (+54.25%), widespread (+448.92%), and severe (+612.78%) OTLDs. Meanwhile, the best RAI values for frequency, duration, intensity, areal extent, and total magnitude of global OTLDs and their 90% CIs are above zero, suggesting that the signal of anthropogenic climate change is strongly detected in the OTLD projections (Fig. 3b–f). This future anthropogenic signal is also detectable at regional scales, i.e., in 27 (90%) of the combinations for the five characteristics across the six regions (Fig. 3b–f). We find that not only the relative changes but also the temporal trends of OTLD characteristics also show significantly (p < 0.0001) enhanced OTLDs, with a duration of 0.8 months·decade-1; intensity of 9.0 × 104 mm·decade-1; maximum area of 3.9 × 105 km2·decade-1; total magnitude of 1.0 × 102 mm·months·decade-1; by the end of the century, as shown in Fig. 3g–j. We repeat the above analyses under SSP370, a moderate-emissions scenario. These future changes in OTLDs under SSP370 are consistent with those under SSP585 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, we next focus on the SSP585 scenario (where GHG emissions play a primary role in anthropogenic climate change) to investigate the impacts of anthropogenic emissions on OTLDs.

a Change in the total frequency of landfalling OTLDs between SSP585 during 2021–2100 and under ALL during 1961–2020. “SSP585 − ALL” indicates the difference between the future projections and historical all-forcings simulations. b–f The same as a, but for anomalies of frequency, duration, intensity, areal extent, and total magnitude between SSP585 during 2071–2100 and under ALL during 1981–2010, respectively. Black dots represent regions with significant differences in OTLD characteristics (p-value < 0.05 based on the student’s t-test). g–j The red lines show mean duration (g), intensity (h), maximum area (i), and total magnitude (j) of OTLDs within a 21-year moving window under ALL and SSP585. Four-time series show a significant trend (Mann-Kendall test at the 0.01% significance level). Shading represents the standard deviation of OTLD characteristics across the multi-model ensemble. The figure is done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/).

We also estimate the response of future OTLD characteristics to different level warmings (Supplementary Fig. 4). OTLDs over the global land surface are expected to become more frequent (+48.15%), persistent (+63.94%), widespread (+401.52%), and severe (+499.71%) at a 3 °C warming. The best RAI of OTLD characteristics over the global and regional scales at the 3 °C warming and their 90% CIs are consistent (90% combinations above zero) with those during 2071–2100, implying the robust anthropogenic signals in OTLD characteristics.

OTLD-linked moisture transport in responses to anthropogenic emissions

To understand the growth of OTLDs based on PME deficits over the six hotspots due to anthropogenic emissions, we investigate moisture transport during OTLDs over these regions (Fig. 4). In comparison with the climatological period, the reduction in moisture transport toward land during the post-landfall periods of OTLDs explains the occurrence and persistence of OTLDs across the three hotspots (WNA, EA, and EAS) in the northern hemisphere. The landward movements of moisture divergence are related to anticyclonic atmospheric patterns over the adjacent oceans (northern Pacific and northern Atlantic) (Fig. 4a–f). For these three hotspots in the northern hemisphere, during OTLDs (including the periods pre- and post-landfall), these movements of moisture divergence away from the oceans lead to a migration of moisture deficit (also see the accumulation of OTLD intensity). This can be seen in the case of the migration of moisture deficit onto WNA from the equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), onto northern EA from the low-latitude Atlantic (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), and onto southeastern EAS from the northwestern Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Previous studies also identified these migrations of moisture deficits (e.g., WNA and EA)5,6, driven by anticyclones originating from the subtropical high-pressure system30,31. In contrast, the weakening OTLDs over EA under AER are associated with cyclone anomalies (weaker anticyclones under AER compared to ALL) reaching EA and the northern Atlantic (Supplementary Fig. 8). The cyclones-related moisture convergence is beneficial for moisture transport to EA, resulting in fewer and weaker OTLDs making landfall in EA (Supplementary Fig. 2). The aerosols in EA through the wind-evaporation-SST (sea surface temperature) feedback32,33, cause the local Atlantic warming. The higher SST leads to a poleward shift in the branch of the Hadley Cell that reduces westerlies34, inhibiting the development of anticyclones over the northern Atlantic. Over EAS, under the aerosol-cloud-monsoon interactions35, aerosols might lead to continental cooling36, thereby reducing the land-ocean contrast. This decreased thermal contrast weakens the East Asian summer monsoon37,38, which could be detrimental to conveying moisture from the Pacific to the Asian hinterland39 (Supplementary Fig. 8), leading to exacerbated moisture deficits.

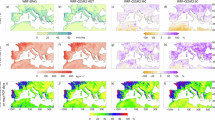

Maps show multi-model mean anomalies of vertically integrated moisture divergence (red areas with negative values indicate moisture divergence) and water vapor flux (black arrows) over WNA (a, b), EA (c, d), EAS (e, f), SSA (g, h), SAF (i, j) and AU (k, l) between ALL during the lifetime of OTLDs (pre-landfall: left column; post-landfall: right column) and ALL-climatology (the climatological mean without considering OTLDs). ALL: 1961–2020; climatological mean: 1981–2010; the pre-landfall period indicates a period from origination to landfalling of each OTLD event; the post-landfall period indicates a period from landfall to extinction of each OTLD event. The figure is done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/).

These above-mentioned atmospheric circulation patterns driving OTLDs over the three hotspots in the northern hemisphere are projected to strengthen under anthropogenic warming40,41,42 (Fig. 5), resulting in stronger OTLDs in the future. Specifically, the ~tenfold strengthening of anticyclones (units of water vapor flux in Fig. 5 vs. those in Fig. 4) over the northern Pacific and northern Atlantic would intensify moisture deficits and their transport landward43. Future migratory trajectories of moisture deficits are the same as the historical ones, but landfalling regions are located further southward (Supplementary Figs. 5–7c–f).

Maps show multi-model mean anomalies of vertically integrated moisture divergence (red areas with negative values indicate moisture divergence) and water vapor flux (black arrows) over WNA (a, b), EA (c, d), EAS (e, f), SSA (g, h), SAF (i, j) and AU (k, l) between SSP585 and ALL during the lifetime of OTLDs (pre-landfall: left column; post-landfall: right column). SSP585: 2021–2100; ALL: 1961–2020. The figure is done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/).

Compared to the northern hemisphere, the moisture transport processes driving OTLDs are more complex for the three hotspots (SSA, SAF, and AU) in the southern hemisphere, and are associated with various circulation patterns (e.g., anticyclones and cyclones) over adjacent oceans (southern Pacific, southern Atlantic, and Indian Ocean) (Fig. 4g–l). Over SSA, there are two pathways for OTLD occurrences (Fig. 4g, h and Supplementary Figs. 9a, b): (i) moisture deficits expanding onto southwestern SSA from the equatorial Pacific due to the moisture divergence associated with northwestward winds; or (ii) moisture deficits migrating onto eastern SSA from the southwestern Atlantic due to the seaward movement of moisture convergence associated with contracting cyclones over the Atlantic. In the future projections, we find the first pathway from the equatorial Pacific would be significantly enhanced, but these intensified OTLDs would be unable to spread inland due to the blocking effect of the Andes on the transport of moisture deficits44,45 (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Figs. 9c–f). For the second pathway from the southwestern Atlantic, we find an emerging anticyclone over the Atlantic (Fig. 5h) that would result in the expansion of moisture deficits northward onto the north of SSA (e.g., stronger OTLDs in northeastern South America; Supplementary Fig. 9c–f).

Over SAF, in the historical simulations, moisture deficits tend to expand onto land from the Atlantic and Indian Oceans (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b) due to moisture divergence linked to anticyclones over the southern Atlantic and Madagascar, respectively (Fig. 4i, j). In the projections, northwestward winds induced by emerging anticyclones over the Atlantic and enhanced anticyclones over Madagascar (Fig. 5i, j) bring moisture deficits onto SAF and maintain the same migratory trajectories as the historical period (Supplementary Fig. 10c–f).

For AU, the interaction between anticyclones over the Indian Ocean and cyclones over the southwestern Pacific lead to northward winds in ALL, causing moisture divergence over the ocean areas around AU (Fig. 4k, l). This moisture divergence leads to moisture deficit expansion onto AU from the Indian Ocean and southwestern Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). In the projections, these circulation patterns over the oceans become more complex (Fig. 5k, l). Moisture from the southern Indian Ocean would be transported to the northern hemisphere by cross-equatorial air flows, forming a widespread region over the southern Indian Ocean with moisture divergence. This widespread moisture divergence region leads to the expansion of moisture deficits onto western AU (Supplementary Fig. 11c–f). In contrast, circulation patterns for the projected weakening OTLDs over northeastern AU are unclear, possibly due to interaction effects among multiple climate modes46,47,48 (e.g., El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Indian Ocean dipole49,50) on moisture transport in this region.

Physical drivers and future risk assessment of OTLDs

Here, we summarize the key mechanisms by which anthropogenic emissions intensify OTLDs from the perspective of moisture transport (Fig. 6a). Due to anticyclone-induced moisture divergence, landward migration and/or expansion of moisture deficits drive the occurrence of OTLDs. These anticyclones-associated atmospheric patterns are likely to strengthen under anthropogenic warming, and hence the landward migration/expansion of moisture deficits also be enhanced, resulting in intensified OTLDs in a high-emissions future.

a Risk levels of OTLDs according to the SOM classification under ALL during 1981–2010 and under SSP585 during 2071–2100 (colors represent increasing hazard). b Contributions of physical factors to the change in integrated moisture divergence (≈PME) between SSP585 and ALL during the post-landfall periods of OTLDs. SSP585: 2021–2100; ALL: 1961–2020. Error bars show the standard deviation across the multi-model ensemble. c Different risk levels for each OTLD characteristic. The subfigures are done in the software R 4.1.2 (https://cran.rproject.org/bin/windows/) and then are merged by using the PowerPoint software of Microsoft 365 (https://www.microsoft.com).

Human-induced intensification of PME-based OTLDs can be explained by both dynamic and thermodynamic drivers16,23,51. Thermodynamically, moisture transport would be enhanced by the warming-driven changes in specific humidity and the land-ocean warming contrast52,53,54, which increases PME in the tropics and high latitudes but decreases PME in the subtropics51,55. Dynamically, atmospheric circulation processes (e.g., shifts in the strength of Walker and Hadley circulations23,56,57,58) driven by anthropogenic warming could lead to complex spatial changes in PME patterns. For instance, the expansion of the Hadley circulations makes the downward branch move toward the poles, leading to reduced PME in the subtropics59,60,61. These thermodynamic and dynamic drivers can be further decomposed into the advection dynamic component, advection thermodynamic component, convergence dynamic component, and convergence thermodynamic component16,62.

We quantified the contributions of all dynamic and thermodynamic components to the changes in integrated moisture divergence (≈PME) between SSP585 and ALL during the post-landfall periods of OTLDs (Fig. 6b). For the six hotspots, the thermodynamic component is an essential driver of OTLDs (contribution: 30% ~ 55%; the range across the six hotspots) to enhance OTLDs, and can be further attributed to the advection thermodynamic component (contribution to the thermodynamic component: 54%–97%) (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Figs. 12–17). Previous findings also found that PME deficits over land (especially at low-mid latitudes) were dominated by the thermodynamic component16,51,63. The thermodynamic responses to anthropogenic warming are expected to lead to global circulation slowdown22,23 (e.g., a reduction of temperature gradients due to enhanced upper-tropospheric warming64,65,66) and greater land-ocean warming contrast53 (i.e., slower increase in humidity over the ocean than over land). As a result, moisture transport from the ocean to land would be weakened54,67,68,69, and hence PME deficits would intensify landward23,52, particularly in the tropics and subtropics.

Finally, we assess past and future risks (i.e., from low-level I to high-level IV) of OTLDs in the past and in future projections by using self-organizing maps (SOM) with unsupervised learning (Fig. 6c). Areas with higher risk levels in the future would experience more frequent, persistent, widespread, and severe OTLDs. Globally, only 15% of land areas show high-level risk in the historical period under ALL, while this percentage is projected to reach 51.2% in the future under SSP585. The regions with the largest expansion of high-level risk are found in the six hotspots (areas with high-level risk account for 37–100% of total areas in the future land surface) (Fig. 6a). The spatial patterns of risk assessments in the historical and future periods are consistent with the patterns in the total magnitude of OTLDs (Supplementary Fig. 18).

In summary, we demonstrate that the historical growth of OTLDs can be attributed to anthropogenic emissions, and this enhancement is likely to grow further under future increasing GHG emissions. Under a high-emissions scenario, about 50.9% of the global population (based on the projected amount of population during 2071–2100) is expected to experience the highest risk of OTLDs in the future. Notably, we find the most populous regions worldwide (e.g., North America, East Asia, and Europe) are exposed to the highest OTLD-induced risks under a warmer climate. These findings underscore the importance of developing adaptation measures to mitigate the future risk of OTLDs in natural ecosystems and human-managed environments.

We have detected robust anthropogenic signals from OTLDs characteristics, but it is unclear whether internal climate variability has an impact on OTLDs. Therefore, understanding whether and how OTLD interacts with other climate modes (e.g., El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Indian Ocean dipole) can provide a more holistic view of its evolution and impacts. In addition, our studies focus on the spatially direct and temporally continuous impacts of oceanic moisture deficits on continents. However, the role of teleconnections in the occurrence and propagation of terrestrial droughts is also not negligible. Terrestrial droughts are not only induced by teleconnections of land-based sources70, but also are likely to be associated with teleconnections of marine sources. Hence, future studies that droughts in global land areas are synchronized or lagged by moisture deficits in marine areas through teleconnection effects, will provide important insights for addressing terrestrial droughts indirectly caused by oceanic moisture deficits.

Methods

CMIP6 outputs—historical simulations and future scenario

We used the CMIP6 model simulations (Supplementary Table 1) covering the historical period (1960–2014; “historical” of CMIP, ALL) and future high-emissions scenario (2015–2100; “ssp585” of ScenarioMIP, SSP585). The corresponding historical and future simulations were merged for each model to obtain a time series over the period 1961–210071. The ALL simulations represent that climate models are forced by both anthropogenic (GHG and AER emissions) and natural external forcings. To distinguish the impact of individual external forcings on OTLDs, we used several external forcing experiments derived from the Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP) of CMIP6, e.g., historical natural (“hist-nat”, NAT), historical greenhouse-gas (“hist-GHG”, GHG), and historical anthropogenic-aerosol (“hist-aer”, AER) forcings72. We also used projections under a moderate-emissions scenario (“ssp370” of ScenarioMIP, SSP370), validating the robustness of projected OTLDs under SSP585. We selected the 10 CMIP6 models that output monthly precipitation (“pr”, mm), evaporation (“evspsbl”, mm), near-surface temperature (“tas”, K), specific humidity (“hus”, kg·kg-1; 19 layers), surface air pressure (“ps”, Pa), meridional winds (“va”, m·s-1; 19 layers), and zonal winds (“ua”, m·s-1; 19 layers) in the above five scenarios. The first ensemble member ‘r1i1p1f1’ was used for each model to avoid considering the variability within each climate model ensemble. All the model outputs were interpolated to 1°× 1° resolution.

Reanalysis data and bias correction algorithm

We identified historical OTLDs using precipitation and evaporation from the state-of-the-art reanalysis dataset, to assess the OTLD simulations by the CMIP6 Global Circulation Models. The reanalysis dataset used is the fifth generation of the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis (ERA5)73. The raw precipitation and evaporation data were also interpolated to 1° × 1° resolution.

Due to the systematic biases of CMIP6 simulations in simulating meteorological variables (precipitation and evaporation) compared with the reanalysis dataset, we applied a bias correction algorithm (i.e., quantile delta mapping (QDM)74) to reduce these biases. We employed the QDM to correct the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of ALL simulations to the CDFs of ERA5. Given the shared similar biases from a specific model under different external forcings75, the difference of CDFs between ALL simulations and ERA5 were applied to adjust CDFs from the simulations under different forcings (NAT, AER, and GHG) and the projections under different scenario (SSP585)76. The bias correction was conducted for each model independently.

Identification of OTLDs

We used a three-dimensional clustering approach to track the spatio-temporal evolution of OTLDs during 1961–2020 in the CMIP6 simulations and ERA5 reanalysis dataset (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for an example). As in previous studies5, we tracked OTLDs in space and time based on a 12-month accumulation of PME anomalies (PMEA). We employed PMEA to calculate the drought index, i.e., the standardized precipitation-evapotranspiration index (SPMEI), using a non-parametric standardization approach9,77,78. SPMEI at the calendar month t is estimated as

where \({\hat{f}}_{i}\left(x\right)\) represents the probability density function at the grid cell i. Given a monthly sequence of values \({{\rm{PMEA}}}_{i,1}\), \({{\rm{PMEA}}}_{i,2}\),…, \({{\rm{PMEA}}}_{i,n}\), the kernel density estimates at a given value x can be obtained by

where \(K\left(x\right)\) represents the Gaussian kernel with bandwidth h and sampling size n. We used a median filter for the SPMEI spatial pattern5,79,80,81,82 to improve the robustness of the identification of drought clusters and selected 0.2 as the drought threshold5,9,77. Spatiotemporally contiguous drought clusters (STCDCs) are tracked based on SPMEI using a drought clustering algorithm5,9,12,83,84,85. This algorithm finds drought cells and merges adjacent cells to identify spatially contiguous drought clusters (SCDC; at least 10,000 km2). SCDCs that share an overlapping area over consecutive timesteps are consolidated into a single STCDC. Finally, STCDCs that originate entirely (i.e., 100%) over the ocean and then spread over land over an area of at least 100,000 km2 are identified as OTLDs5.

Characteristics of OTLDs

The following drought characteristics are extracted from all identified OTLDs: (1) the duration (unit: month), defined as the lifetime of each OTLD during the post-landfall period; (2) the maximum area (km2), the spatial extent of all land grid cells of an OTLD; (3) the intensity (mm), the sum PMEA of all land grid cells of an OTLD; and (4) the total magnitude (mm·month), a synthetic index describing the duration, area, and intensity86,87, defined as

where i is a grid cell of SCDC in time t for the duration with grid area Ai. A larger total magnitude indicates stronger OTLDs. In this study, only the top 100 OTLD events based on total magnitude are selected from each CMIP6 model under the ALL and NAT scenarios during 1961–2020, because we focus on the impacts of persistent, widespread, and intense OTLDs. We also mapped these characteristics at each grid cell to assess the spatial patterns of OTLDs5. The accumulated intensity of OTLDs is calculated by mapping the PMEA of all OTLDs during the post/pre-landfall periods.

Relative anthropogenic index

The relative anthropogenic index (RAI) is used to detect the signal of anthropogenic climate change quantificationally88,89 as:

where Ii is the characteristic of OTLDs for grid cell i in area S. A positive (negative) RAI indicates increased (decreased) characteristics of OTLDs due to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change. To quantify the RAI uncertainty, we use a bootstrapping approach to resample RAI 10,000 times from CMIP6 models to generate 90% CIs. If the 90% CIs are both positive (negative), the median RAI is considered statistically significant, and then the signal of anthropogenic climate change is considered detectable88,89.

Moisture transport and physical drivers

The atmospheric moisture budget principle asserts that the difference between precipitation and evaporation (i.e., PME) equals the negative divergence of vertically integrated water flux17,18,19.

where Q is the vertically integrated moisture transport, ∇∙ is the divergence operator, ρ is the density of water, g is the gravitational acceleration, pt is the pressure at the top of the atmosphere, ps is the near-surface pressure, q is the specific humidity, and V is the mean wind field (meridional wind v and zonal wind u). As OTLDs are the result of long-term PME deficits, moisture divergence is approximately estimated as

The changes in moisture divergence between future and historical periods can be decomposed as17,90

where the subscript f and h, respectively, indicate the future period of 2015–2100 under SSP585 and historical ALL simulations during 1961–2014. The dynamic component represents changes in horizontal wind, the thermodynamic component represents changes in specific humidity, and the nonlinear component represents the product of changes in specific humidity and wind16,17,18,19,62,91. In addition, moisture transport can be composed of advection transport and convergence transport19,92,93

Further, the changes in moisture divergence can be decomposed into multiple terms as follows:

The contributions of the thermodynamic and dynamic components to PME are normalized to within –100% and 100%.

Synthetic risk assessment

The SOM algorithm94 is a practical classification framework for drought95,96,97,98. Here, we select the frequency, duration, intensity, and areal extent of OTLDs under historical and future 30-year climatological periods, namely the historical ALL simulations during 1981–2010 and the SSP585 projections during 2071–2100. We produce a matrix (43,956 grid cells × 4 metrics) as input data. After data standardization, we determine the best SOM dimension (i.e., 3 × 2 = 6 nodes in this study) by calculating the quantization error, which evaluates the ability of the neural network to differentiate input data95,99.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available online. The CMIP6 model simulations are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/; the ERA-5 data are available at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era5; the global population data from Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project are available at https://data.isimip.org.

Code availability

The Python (version 3.9) and R (version 4.1.2) codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author (X.G.) upon reasonable request.

References

Sternberg, T. Regional drought has a global impact. Nature 472, 169–169 (2011).

McNutt, M. The drought you can’t see. Science 345, 1543–1543 (2014).

Mishra, A. K. & Singh, V. P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 391, 202–216 (2010).

Peterson, T. J., Saft, M., Peel, M. C. & John, A. Watersheds may not recover from drought. Science 372, 745–749 (2021).

Herrera‐Estrada, J. E. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Landfalling droughts: global tracking of moisture deficits from the oceans onto land. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026877 (2020).

Shen, Z. et al. Drying in the low-latitude Atlantic Ocean contributed to terrestrial water storage depletion across Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 13, 1849 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Oceanic climate changes threaten the sustainability of Asia’s water tower. Nature 615, 87–93 (2023).

Yuan, X. et al. Anthropogenic shift towards higher risk of flash drought over China. Nat. Commun. 10, 4661 (2019).

Samaniego, L. et al. Anthropogenic warming exacerbates European soil moisture droughts. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 421–426 (2018).

Chiang, F., Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity. Nat. Commun. 12, 2754 (2021).

Pokhrel, Y. et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 226–233 (2021).

Rakovec, O. et al. The 2018–2020 multi‐year drought sets a new benchmark in Europe. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002394 (2022).

Yuan, X. et al. A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science 380, 187–191 (2023).

Feng, S. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions drive global dryland expansion but not spatial patterns of change in aridification. J. Clim. 35, 6501–6517 (2022).

Wang, Y. & Yuan, X. Anthropogenic speeding up of South China flash droughts as exemplified by the 2019 summer-autumn transition season. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091901 (2021).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

Zhou, S. et al. Diminishing seasonality of subtropical water availability in a warmer world dominated by soil moisture–atmosphere feedbacks. Nat. Commun. 13, 5756 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere feedbacks mitigate declining water availability in drylands. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 38–44 (2021).

Guan, Y. et al. Tracing anomalies in moisture recycling and transport to two record-breaking droughts over the Mid-to-Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Hydrol. 609, 127787 (2022).

Bony, S. et al. Robust direct effect of carbon dioxide on tropical circulation and regional precipitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 447–451 (2013).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 228–232 (2002).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Zaitchik, B. F., Rodell, M., Biasutti, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Wetting and drying trends under climate change. Nat. Water 1, 502–513 (2023).

Barnes, E. A. & Polvani, L. Response of the midlatitude jets, and of their variability, to increased greenhouse gases in the CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 26, 7117–7135 (2013).

Yin, J. H. A consistent poleward shift of the storm tracks in simulations of 21st century climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L18701 (2005).

Gao, Y., Lu, J. & Leung, L. R. Uncertainties in projecting future changes in atmospheric rivers and their impacts on heavy precipitation over Europe. J. Clim. 29, 6711–6726 (2016).

Zavadoff, B. L. & Kirtman, B. P. Dynamic and thermodynamic modulators of European atmospheric rivers. J. Clim. 33, 4167–4185 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Swain, D. L. et al. Remote linkages to anomalous winter atmospheric ridging over the northeastern Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 122, 12,194–12,209 (2017).

Swain, D. L., Horton, D. E., Singh, D. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Trends in atmospheric patterns conducive to seasonal precipitation and temperature extremes in California. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501344 (2016).

Chang, P., Ji, L. & Li, H. A decadal climate variation in the tropical atlantic ocean from thermodynamic air-sea interactions. Nature 385, 516–518 (1997).

Xie, S.-P. A dynamic ocean–atmosphere model of the tropical atlantic decadal variability. J. Clim. 12, 64–70 (1999).

Murakami, H. Substantial global influence of anthropogenic aerosols on tropical cyclones over the past 40 years. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9493 (2022).

Tsai, I., Wang, W., Hsu, H. & Lee, W. Aerosol effects on summer monsoon over asia during 1980s and 1990s. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 121, 761–11,776 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Aerosol and monsoon climate interactions over Asia. Rev. Geophys. 54, 866–929 (2016).

Mu, J. & Wang, Z. Responses of the East Asian summer monsoon to aerosol forcing in CMIP5 models: The role of upper-tropospheric temperature change. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 1555–1570 (2021).

Song, F., Zhou, T. & Qian, Y. Responses of east asian summer monsoon to natural and anthropogenic forcings in the 17 latest CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 596–603 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Attribution of the record‐breaking extreme precipitation events in july 2021 over central and eastern China to anthropogenic climate change. Earth’s Future 11, e2023EF003613 (2023).

He, C., Wu, B., Zou, L. & Zhou, T. Responses of the summertime subtropical anticyclones to global warming. J. Clim. 30, 6465–6479 (2017).

He, C. & Zhou, T. Distinct responses of north Pacific and north Atlantic SUmmertime Subtropical Anticyclones to Global Warming. J. Clim. 35, 8117–8132 (2022).

Huang, Y., Li, X. & Wang, H. Will the western Pacific subtropical high constantly intensify in the future? Clim. Dyn. 47, 567–577 (2016).

Zahn, M. & Allan, R. P. Quantifying present and projected future atmospheric moisture transports onto land: landward atmospheric moisture transports. Water Resour. Res. 49, 7266–7277 (2013).

Insel, N., Poulsen, C. J. & Ehlers, T. A. Influence of the Andes Mountains on South American moisture transport, convection, and precipitation. Clim. Dyn. 35, 1477–1492 (2010).

Minvielle, M. & Garreaud, R. D. Projecting rainfall changes over the South American Altiplano. J. Clim. 24, 4577–4583 (2011).

Bauer-Marschallinger, B., Dorigo, W. A., Wagner, W. & Van Dijk, A. I. J. M. How oceanic oscillation drives soil moisture variations over mainland Australia: an analysis of 32 years of satellite observations. J. Clim. 26, 10159–10173 (2013).

Ummenhofer, C. C. et al. What causes southeast Australia’s worst droughts? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L04706 (2009).

Holgate, C., Evans, J. P., Taschetto, A. S., Gupta, A. S. & Santoso, A. The impact of interacting climate modes on East Australian precipitation moisture sources. J. Clim. 35, 3147–3159 (2022).

Le, T. & Bae, D.-H. Response of global evaporation to major climate modes in historical and future coupled model intercomparison project phase 5 simulations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 1131–1143 (2020).

Le, T. & Bae, D. Causal impacts of el niño–southern oscillation on global soil moisture over the period 2015–2100. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002522 (2022).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. The response of precipitation minus evapotranspiration to climate warming: why the “Wet-Get-Wetter, Dry-Get-Drier” scaling does not hold over land. J. Clim. 28, 8078–8092 (2015).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Land–ocean warming contrast over a wide range of climates: convective quasi-equilibrium theory and idealized simulations. J. Clim. 26, 4000–4016 (2013).

Joshi, M. M., Gregory, J. M., Webb, M. J., Sexton, D. M. H. & Johns, T. C. Mechanisms for the land/sea warming contrast exhibited by simulations of climate change. Clim. Dyn. 30, 455–465 (2008).

Fasullo, J. T. Robust land–ocean contrasts in energy and water cycle feedbacks. J. Clim. 23, 4677–4693 (2010).

Chou, C., Neelin, J. D., Chen, C.-A. & Tu, J.-Y. Evaluating the “Rich-Get-Richer” mechanism in tropical precipitation change under global warming. J. Clim. 22, 1982–2005 (2009).

Karnauskas, K. B. & Ummenhofer, C. C. On the dynamics of the Hadley circulation and subtropical drying. Clim. Dyn. 42, 2259–2269 (2014).

Tokinaga, H., Xie, S.-P., Deser, C., Kosaka, Y. & Okumura, Y. M. Slowdown of the Walker circulation driven by tropical Indo-Pacific warming. Nature 491, 439–443 (2012).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing. Nature 441, 73–76 (2006).

Lau, W. K. M. & Kim, K.-M. Robust Hadley Circulation changes and increasing global dryness due to CO2 warming from CMIP5 model projections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 3630–3635 (2015).

Kang, S. M. & Lu, J. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming: winter versus summer. J. Clim. 25, 8387–8393 (2012).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007).

Li, L., Li, W. & Barros, A. P. Atmospheric moisture budget and its regulation of the summer precipitation variability over the Southeastern United States. Clim. Dyn. 41, 613–631 (2013).

Elbaum, E. et al. Uncertainty in projected changes in precipitation minus evaporation: dominant role of dynamic circulation changes and weak role for thermodynamic changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097725 (2022).

Qu, X. & Huang, G. The Global warming–induced south asian high change and its uncertainty. J. Clim. 29, 2259–2273 (2016).

Ma, J. & Yu, J.-Y. Paradox in South Asian summer monsoon circulation change: lower tropospheric strengthening and upper tropospheric weakening: Ma and Yu: SASM change: lower increase/upper reduce. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2934–2940 (2014).

Ma, J., Xie, S.-P. & Kosaka, Y. Mechanisms for tropical tropospheric circulation change in response to global warming. J. Clim. 25, 2979–2994 (2012).

Simmons, A. J., Willett, K. M., Jones, P. D., Thorne, P. W. & Dee, D. P. Low-frequency variations in surface atmospheric humidity, temperature, and precipitation: Inferences from reanalyses and monthly gridded observational data sets. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D01110 (2010).

O’Gorman, P. A. & Muller, C. J. How closely do changes in surface and column water vapor follow Clausius–Clapeyron scaling in climate change simulations? Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 025207 (2010).

Rowell, D. P. & Jones, R. G. Causes and uncertainty of future summer drying over Europe. Clim. Dyn. 27, 281–299 (2006).

Mondal, S. K., Mishra, A., Leung, R. & Cook, B. Global droughts connected by linkages between drought hubs. Nat. Commun. 14, 144 (2023).

Donat, M. G., Lowry, A. L., Alexander, L. V., O’Gorman, P. A. & Maher, N. More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 508–513 (2016).

Gillett, N. P. et al. The Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP v1.0) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3685–3697 (2016).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Cannon, A. J., Sobie, S. R. & Murdock, T. Q. Bias correction of GCM precipitation by quantile mapping: How well do methods preserve changes in quantiles and extremes? J. Clim. 28, 6938–6959 (2015).

Yuan, X., Jiao, Y., Yang, D. & Lei, H. Reconciling the attribution of changes in streamflow extremes from a hydroclimate perspective. Water Resour. Res. 54, 3886–3895 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Detection and attribution of human influence on the global diurnal temperature range decline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097155 (2022).

Samaniego, L., Kumar, R. & Zink, M. Implications of parameter uncertainty on soil moisture drought analysis in Germany. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 47–68 (2013).

Sheffield, J. A simulated soil moisture based drought analysis for the United States. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D24108 (2004).

Andreadis, K. M., Clark, E. A., Wood, A. W., Hamlet, A. F. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Twentieth-century drought in the conterminous United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 6, 985–1001 (2005).

Herrera-Estrada, J. E. & Sheffield, J. Uncertainties in future projections of summer droughts and heat waves over the contiguous United States. J. Clim. 30, 6225–6246 (2017).

Vernieuwe, H., De Baets, B. & Verhoest, N. E. C. A mathematical morphology approach for a qualitative exploration of drought events in space and time. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 530–543 (2020).

Sheffield, J., Andreadis, K. M., Wood, E. F. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Global and continental drought in the second half of the twentieth century: severity–area–duration analysis and temporal variability of large-scale events. J. Clim. 22, 1962–1981 (2009).

Herrera‐Estrada, J. E. et al. Reduced moisture transport linked to drought propagation across North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5243–5253 (2019).

Herrera‐Estrada, J. E., Satoh, Y. & Sheffield, J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of global drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2254–2263 (2017).

Diaz, V., Corzo Perez, G. A., Van Lanen, H. A. J., Solomatine, D. & Varouchakis, E. A. An approach to characterise spatio-temporal drought dynamics. Adv. Water Resour. 137, 103512 (2020).

Lo, S.-H., Chen, C.-T., Russo, S., Huang, W.-R. & Shih, M.-F. Tracking heatwave extremes from an event perspective. Weather Clim. Extrem. 34, 100371 (2021).

Wang, J. & Yan, Z. Rapid rises in the magnitude and risk of extreme regional heat wave events in China. Weather Clim. Extrem. 34, 100379 (2021).

Duan, W. et al. Changes in temporal inequality of precipitation extremes over China due to anthropogenic forcings. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 33 (2022).

Konapala, G., Mishra, A. & Leung, L. R. Changes in temporal variability of precipitation over land due to anthropogenic forcings. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 024009 (2017).

Baek, S. H. & Lora, J. M. Counterbalancing influences of aerosols and greenhouse gases on atmospheric rivers. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 958–965 (2021).

Zhang, C. Moisture sources for precipitation in Southwest China in summer and the changes during the extreme droughts of 2006 and 2011. J. Hydrol. 591, 125333 (2020).

Roxy, M. K. et al. A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India. Nat. Commun. 8, 708 (2017).

Yin, J. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389 (2018).

Kohonen, T. Essentials of the self-organizing map. Neural Netw. 37, 52–65 (2013).

Zeng, P. et al. Mapping future droughts under global warming across China: A combined multi-timescale meteorological drought index and SOM-Kmeans approach. Weather Clim. Extrem. 31, 100304 (2021).

Markonis, Y. et al. The rise of compound warm-season droughts in Europe. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb9668 (2021).

Harrington, L. J. et al. Investigating event‐specific drought attribution using self‐organizing maps. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 12,766–12,780 (2016).

Parsons, L. A. & Coats, S. Ocean‐atmosphere trajectories of extended drought in southwestern North. Am. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 8953–8971 (2019).

Rousi, E., Kornhuber, K., Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Luo, F. & Coumou, D. Accelerated western European heatwave trends linked to more-persistent double jets over Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 13, 3851 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFE0103900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371041 and 41901041), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (2023AFB566), Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan-Shuguang (2023020201020333), the Belt and Road Special Foundation of the National Key Laboratory of Water Disaster Prevention (2022nkms03), the CRSRI Open Research Program (CKWV20231194/KY), and the open funding from the Institute of Arid Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration, Lanzhou (IAM202214). L.J.S. is supported by UKRI (MR/V022008/1) and NERC (NE/S015728/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G. designed this study. Y.G. conducted the calculations and analyses. X.G. and Y.G. wrote the first draft. All the authors contributed to the discussion, editing, and improving the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guan, Y., Gu, X., Slater, L.J. et al. Increase in ocean-onto-land droughts and their drivers under anthropogenic climate change. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00523-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00523-y

This article is cited by

-

Anthropogenic enhancement of subsurface soil moisture droughts

Nature Climate Change (2025)

-

Spatial and temporal patterns of precipitation concentration and their associated risks

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Frequent land-ocean transboundary migration of tropical heatwaves under climate change

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Assessment of winter three-dimensional extreme cold events over the Northern Hemisphere during 1959–2020 based on CMIP6 models

Climate Dynamics (2025)

-

Droughts are blowing in the wind

Nature Water (2024)