Abstract

Recently, nitrate (NO3–) levels in winter pollution in eastern China have been increasing yearly and have become the main component of PM2.5. The factors contributing to this rise in surface NO3– concentrations remain unclear, complicating the development of targeted pollution control measures. This study utilizes observational data from Shanghai during the winter 2019, alongside box model simulations, to recreate the NO3− pollution event and identify the key factors in the growth process. The analysis demonstrated that a rise in winter ozone levels significantly promotes NO3– production by facilitating NOx conversion via gas-phase and heterogeneous reactions. These findings could explain the correlation between the synchronous increase of surface ozone and NO3− in recent years. Furthermore, simulation of control strategies for NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) identified an approach centered on ozone reduction as notably effective in mitigating winter NO3– pollution in the Yangtze River Delta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Chinese government has implemented stringent air pollution control policies since 2013. However, the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) is characterized by severe air pollution1,2, evident from the frequent exceedance of the Chinese air quality second-level standard for 24-h average PM2.5 concentration, which is ≤75 μg m−3. During these high pollution episodes, PM2.5 concentrations are often compounded by increased levels of water-soluble inorganic salts, including sulfate (SO42−) and nitrate (NO3−)3. While the reduction in sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions has successfully decreased SO42− concentrations4,5, a similar reduction strategy for nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions has not effectively reduced NO3− levels6,7. Instead, there has been a significant increase in the nitrogen-to-sulfur ratio in PM2.5, highlighting a growing proportion of NO3− in PM2.5 during the winter season8,9. Consequently, NO3− pollution has emerged as a primary target for air quality management in the YRD3,10.

Nitrate formation involves complex multiphase chemical reactions. During the daytime, NO2 reacts with the hydroxyl radical (OH) to produce gaseous nitric acid (HNO3). Subsequently, under ammonia-rich conditions, this reaction can proceed quickly and produce high concentrations of ammonium nitrate11,12. At nighttime, NO3− mainly originates from the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 on wet particles, contributing to 56–97% of nocturnal nitrate formation13,14. While numerous studies have explored these formation mechanisms concerning local NO3− and PM2.5 pollution, the correlation between nitrate and O3 pollution has not been adequately addressed, particularly in China15. Nitrate formation is influenced by the concentration of NOx precursors and the levels of O3 produced through NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) interaction16. Elevated O3 levels during the daytime promote HNO3 formation (reactions 1-2)17, while nighttime nitrate production predominantly occurs through N2O5 hydrolysis (reaction 3) initiated by NO3 (reaction 4), which itself is produced from O3 reacting with NO2 (reaction 5). This suggests that nighttime O3 concentration has a significant effect on nitrate production18. The relationship between NO3− and NOx emissions is nonlinear, with variations depending on O3 sensitivity, highlighting the complex interaction between nitrate and O3 levels19,20. Understanding this relationship is crucial for devising strategies that simultaneously address O3 and PM2.5 pollution21.

In this study, we focus on elucidating the critical processes and variables influencing winter nitrate enhancement in the YRD, emphasizing the role of O3 as a photochemical oxidant. Unlike prior studies by Zhou et al.7 and Zang et al.22, which respectively addressed N2O5 hydrolysis and atmospheric oxidation capacity, our work conducts a thorough analysis of the impact of O3 on nitrate pollution through direct measurements and the observation-based model (OBM) simulations. Advancing the discussion initiated by Fu et al.17 regarding photochemical oxidants, our research offers a detailed examination of the factors driving nitrate formation and suggests potential for coordinated O3 and PM2.5 mitigation strategies. The observation data provide a regional picture of winter nitrate pollution in the YRD and a specific dataset to evaluate the model capacity for simulating the nitrate pollution. Our results indicate surface O3 levels have a crucial role in shaping and regulating nitrate pollution in the YRD region during winter.

Results and discussion

Enhanced winter nitrate pollution amid increasing ozone levels

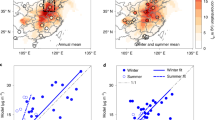

Since the implementation of stringent air quality measures in 2013, the YRD region has seen notable improvements in air quality, as evidenced by the decline in PM2.5 and NO2 levels, especially in densely populated areas like Shanghai and its surroundings (Fig. 1A, B and Supplementary Fig. 1). However, O3 pollution has shown a contrary trend, increasing over time, which is depicted in Fig. 1C. The average MDA8 O3 level in winter 2020 exceeded that of 2014 across most of the YRD, partly due to the uncoordinated NOx and VOC reductions that favorable for O3 photochemical production23.

A–C Reductions of winter Yangtze River Delta (YRD) mean PM2.5, NO2 and MDA8 O3 concentrations between 2014 and 2020 (negative values). D Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on O3 maximum production rates. The pre-lockdown (Pre-lock.) case and the Lockdown (Lock.) case scenarios represent cases without and with COVID lockdown emission reduction, respectively. NOx scenario represents the impact of reducing only NOx emissions during the lockdown, while VOCs scenario represent the impact of reducing only VOCs emissions. Other scenario refers to the additional effects caused by other pollutants and meteorological factors. E Temporal trends in winter NO3− and SO42− concentrations and contribution to PM2.5 in Shanghai from 2013 to 2020. Note that the data for 2016 is taken from the PM1.

Our prior research21, leveraging COVID-19 lockdown data and chemical modeling, confirmed that the increase in surface O3 in YRD is primarily due to human activities rather than meteorological conditions. During the lockdown, emission reductions led to an increase in the maximum rate of O3 production in the YRD by 0.73 ppb h−1 (Fig. 1D). Specifically, a 60% reduction in NOx emissions resulted in a 4 ppb h−1 increase in the maximum O3 production rate, a 22% reduction in VOCs emissions led to a 3.3 ppb h−1 decrease in this rate. Thus, the significant rise in surface O3 (89%) is largely due to the increased O3 production caused by NOx abatement exceeding the decrease in O3 production triggered by VOCs abatement. Meanwhile, the nitrate levels in the YRD have also increased, indicating a complex challenge in managing air quality24.

Figure 1E presents an analysis of the variations in winter concentrations of NO3− and SO42− in the YRD from 2013 to 202017,25,26,27,28,29. In winter 2020, SO42− concentration significantly fell from 13.0 μg/m3 to 5.7 μg/m3, reducing its contribution to PM2.5 from 20% to 15%. This decline is mainly due to a substantial decrease in SO2 emission in the YRD30. In contrast, the NO3− concentration saw a slight increase from 13.2 μg/m3 to 15.5 μg/m3 during the same period, raising its contribution to PM2.5 from 20% to 33%. This marks NO3− as an increasingly predominant pollutant in PM2.5, likely due to a rise in N2O5 hydrolysis, encouraged by higher surface O3 levels18. Other studies have also indicated that surface O3 has been steadily increasing21. It is crucial to explore the relationship between O3 growth and NO3− pollution to fully understand and mitigate the PM2.5 and O3 combined pollution problem in the YRD.

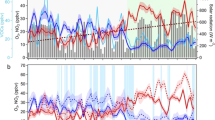

Figure 2A–E shows a series of data on temperature (TEMP), relative humidity (RH), and air pollutants, including NO3−, in Shanghai from January 1 to February 29, 2019. To effectively investigate the characteristics of NO3− pollution, we classified days with average NO3− levels of 20 μg/m3 or higher as NO3− pollution (NP) days, and those below this threshold as non-NO3− pollution (NNP) days. Five NP events were recorded during this period, totaling 12 days, all featuring pronounced increases in NO3−, NOx, and VOCs levels (Fig. 2B). Notably, NO3− concentrations were 270% higher during NP days (32 μg m−3) compared to NNP days (8.4 μg m−3), with a similar upward trend observed for HNO3, which increased by 177% (Fig. 2F). The rapid growth of TNO3 ( = NO3− + HNO3) during NP days may have been a consequence of an increase in its precursors, namely HONO, NOx, and VOCs, which were increased by 110%, 106%, and 87%, respectively. Temperature also played a role, enhancing the chemical reactions that form TNO3. Our analysis indicates a strong correlation between NO3–, HNO3, and their precursors, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.4 to 0.55 (Supplementary Fig. 2). This pattern is consistent with findings from Nanjing18, where high NO2 and VOCs levels accelerated nocturnal NO3 formation. Additionally, we found HNO3 is inversely related to RH, with high humidity slowing photochemical reactions and reducing HNO3 formation31. The contribution of NO3− to PM2.5 also increased from 24% during NNP days to 34% during NP days, highlighting that secondary oxidation processes in the YRD region are more severe25,32.

The figure shows the time series of meteorological parameters and chemical species measured in shanghai on Jan 1–Feb 28, 2019. UTC + 8 denotes Coordinated Universal Time +8 h and represents local solar time in hours. A Surface temperature (TEMP) and relative humidity (RH); B NO2 and VOCs concentrations; C NO and HONO concentrations; D NO3− and HNO3 concentrations; E O3 and PM2.5 concentrations. Here, we define daily average NO3− concentration ≥20 μg m−3 as nitrate pollution (NP) and its <20 μg m−3 as non-nitrate pollution (NNP). The gray area in subfigures A-E is the NP. F The distribution of the above 10 meteorological parameters and chemical species in NNP and NP. The box plot provides the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of the source sample data, and the red pentagrams represent the average.

In this study, a comprehensive source and sink of NO3− were added to the OBM model (Fig. 3A and Methods), and this model was often used to simulate NO3− pollution events (Fig. 3B)18,22,33,34,35,36,37. To minimize model uncertainty, we conducted simulations in three distinct parts: the first simulation covered January 3 to January 16, addressing the first two NO3− pollution events; the second simulation spanned from January 8 to January 27, capturing the third and fourth events; and the third simulation ran from February 13 to February 27, 2020, encompassing the fifth event. The results, depicted in Fig. 3C–E, indicated that the improved OBM model effectively simulated the NO3− concentration during the pollution events (R2 = 0.71–0.85). Previous studies have shown that this model can also reproduce O3 photochemical production and atmospheric free radical chemistry38. Consequently, the OBM model serves as a valuable tool for dissecting the causes of NO3− pollution in the YRD during winter, particularly in relation to ozone and free radical chemistry.

Key processes and factors driving the winter nitrate formation

To better understand the common features of NO3− pollution events during winter and to investigate the variations in pollutants and chemical reactions, we analyzed five complete pollution events as outlined in Fig. 4, with the specific dates detailed in Supplementary Table 1. A complete pollution event encompasses the episode and the two days before and after, totaling 120 hours, which helps delineate the meteorological and chemical transitions distinctly39. These transitions are divided into three periods: an increasing period of NO3− (first 48 h), a stable high concentration period (48 to 72 h), and a decreasing period (72–120 h), as illustrated in Fig. 4A. During the first period, we observed a consistent increase in NO3−, peaking at about 31 μg/m3 with a growth rate of 0.26 μg/m3 per hour (R2 = 0.65). PM2.5 concentration also increased from 26.5 μg m−3 to 85 μg m−3. There was a notable increase in both NOx and VOCs, with rates of 0.24 ppb h−1 (R2 = 0.32) and 0.31 ppb h−1 (R2 = 0.48), respectively. Notably, O3 levels stayed elevated during this period (Figure S5A, B). The parallel increases in NO3− with NOx, VOCs, and O3 implies that the build-up of NO3− could be due to a boost in atmospheric chemical reactions22.

Figure 4B offers further evidence of the amplification of NO3− chemical production during the initial 48 hours, characterized by accelerated N2O5 hydrolysis at night (19:00–7:00) and stronger NO2 + OH reactions during the daytime (8:00-18:00). During the initial stage (0–24 h), the O3 concentration was higher at night (with a maximum of 31 ppb), and with a gradual increase in NO2 levels, N2O5 was hydrolyzed via a chain reaction7 with a maximum hydrolysis rate of 4.3 μg m−3 h−1. However, during the later stage (24–48 h), a reduction in nocturnal O3 led to decreased N2O5 hydrolysis rates, while daytime NO2 + OH reactions increased, pushing the average NO3− formation rate from 1.1 μg m−3 h−1 to 1.5 μg m−3 h−1. This increase likely stems from elevated daytime O3 and OH, enhancing the atmospheric oxidizing capacity (AOC)40. In ammonia-rich conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3C), the gas-phase HNO3 synthesized from the NO2 + OH reaction was rapidly converted to particle-phase6. During this period, the NO3− production rate was rapid; however, due to elevated wind speeds (Supplementary Fig. 3B), this resulted in a reduced accumulation of NO3− in the atmosphere. Furthermore, a notable increase in the net O3 production rate occurred (Supplementary Fig. 4), likely due to reduced humidity (Supplementary Fig. 3D) and increased NOx and VOC levels31,41. The calculation of the net O3 production rate here refers to the study by Chen et al.38. Previous studies have confirmed a marked positive correlation between daytime O3 levels and AOC42, implying that the increase in O3 concentration might reflect the enhanced daytime NO3− chemical production. Generally, our analysis indicates that favorable weather conditions and rising surface O3 levels support varied NO3− formation pathways, which aligns with the gradual NO3− concentration growth and its contribution to PM2.5 in the YRD region, amidst increasing O3 concentrations.

The second period of NO3− pollution is marked by a stabilization period, where the hourly average concentration of NO3− levels off at 30.7 μg/m3, observed during times of low wind speeds and coinciding with high PM2.5 concentrations (hourly average: 91.8 μg/m3). Despite still high NOx and VOCs concentrations, nighttime N2O5 hydrolysis slows down, probably due to decreased levels of O3 and AOC levels (Fig. 4). Conversely, the daytime NO2 + OH reaction reached its maximum value (3.8 μg m−3 h−1) during this period, maintaining high NO3− concentrations in reaction with adequate TNH3. As the TEMP rises and RH drops (Supplementary Fig. 3D), we observed peak daytime AOC levels (9.4 × 106 mole cm−3 s−1) and O3 production rates (2.7 ppb h−1), with O3 reaching up to 40 ppb, the highest during entire pollution events. These findings also imply a significant correlation between O3 levels and NO3− production. With the gradual decrease in the overall levels of precursor pollutants such as NOx, VOCs, and TNH3, coupled with an increase in wind speed, the pollution event enters a period of decline (Supplementary Fig. 3). This period shows a decrease in N2O5 hydrolysis and NO2 + OH reaction rates, although AOC and O3 production remain steady. Notably, nighttime VOC concentrations might briefly rise because of local emissions, leading to a significant increase in AOC41. The high levels of O3 at night throughout the entire pollution event could be due to intense vertical and horizontal transportation in the YRD. It should be noted that N2O5 hydrolysis is the main source of nighttime NO3−, while NO2 + OH is the main daytime source during each period of NO3− pollution. Obviously, our findings show the high concentration of O3 exacerbates the production of NO3− during both nighttime and daytime. This indicates that reducing NOx and VOCs emissions could synergistically control O3 and NO3–, addressing the combined O3 and PM2.5 pollution issue.

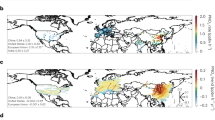

Response of winter NO3 − to emissions reductions

We studied nitrate pollution in the YRD and found that NO3– levels also increased in other Chinese areas where clean air policies were gradually implemented, especially the North China Plain (NCP) and Pearl River Delta (PRD). PM2.5, O3 and NO2 concentrations monitored by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment were used to investigate the formation process of nitrate pollution in Chinese cities, due to the lack of different regional NO3− concentrations and its strong positive correlation with PM2.5 (R2 = 0.93 in this study, Fig. S4). In this study, nitrate pollution is described as having a daily mean PM2.5 concentration exceeding 75 μg m−3 consistent with the Chinese Ambient Air Quality Standards. During the pollution period, the nation’s PM2.5 average concentration peaked at 111 μg m−3, surpassing both pre-pollution levels (53 μg m−3) and post-pollution levels (51 μg m−3) (Fig. 5A–C and Methods). The countrywide trend of PM2.5 concentration changes reveals a gradual increase over the 48 hours before pollution onset (Fig. 5D). This may be due to rising NO2 levels and stable high O3 concentration, which promotes the secondary formation of nitrate (Supplementary Fig. 5A, E). The PRD region exhibited the most significant PM2.5 and NO2 increases during this period, suggesting a more pronounced contribution of nitrate to PM2.5 compared to NCP and YRD (Fig. 4E–G and Supplementary Fig. 5B–D). Notably, the peak O3 concentrations on the day of pollution occurred in the YRD and PRD regions, in contrast to the NCP with the lowest levels (Supplementary Fig. 5F–H), which may be attributable to the higher PM2.5 concentration in the NCP impeding the photochemical synthesis of O3 (Fig. 5E)43. The simultaneous increase of PM2.5 and NO2 emphasizes the significance of limiting NO3− accumulation as a strategy to mitigate PM2.5 pollution effectively in both national and urban areas.

A The spatial distribution of PM2.5 before the episodes. B The spatial distribution of PM2.5 during the episodes. C The spatial distribution of PM2.5 after the episodes. D–G are the temporal variations of PM2.5 before and after the pollution episode for the Nation, NCP, PRD, and YRD, respectively. The yellow line represents the 2021 variations in the corresponding regions. H Responses of NO3− concentrations and aerosol pH to the different TNH3 reduction scenarios. (I) Average daily NO3− concentrations and O3 max production rate for pollution episodes at an annual VOCs/NOx reduction ratio of 9%/4.5%.

Two primary strategies are currently employed to mitigate NO3− formation: (1) reducing emissions of ammonia (TNH3) to influence the thermodynamic balance between NO3− and HNO3, thus controlling NO3− levels44; and (2) decreasing emissions of NOx and VOCs to restrict the chemical synthesis of NO3− and HNO3. To assess the effect of TNH3 emission reduction on NO3– levels, we initially employed a thermodynamic model (ISORROPIA II). A more comprehensive sensitivity analysis was carried out by inputting hourly mean ion concentrations and meteorological factors during All Sampling Time (AST), NP and NNP into ISORROPIA II (Supplementary Table 2). Figure 5H illustrates the aerosol NO3− concentration and pH variations under diverse TNH3 reduction conditions. According to Fig. 5H, reducing TNH3 emissions from 0% to 40% minimally decreased NO3– concentrations during NP days (2 μg m−3) and maximally during NNP days (10 μg m−3). However, this reduction in NO3– was accompanied by a substantial decrease in aerosol pH during all days, indicating an increase in acidity and potential for acid rain development. This outcome supports Liu et al.‘s findings that while ammonia emission control has mitigated haze and nitrogen deposition in China, it could also worsen acid rain problems44. When TNH3 emissions were continuously reduced by 80%, we observed that the NO3– concentration dropped to approximately 0 μg/m3 in all three scenarios, with the pH levels reaching strongly acidic conditions. Notably, when TNH3 reduction reached 70%, a transient increase in pH was observed during NP days before it quickly declined.

The findings elucidated herein reveal that diminishing TNH3 emissions notably heightens aerosol acidity, potentially leading to adverse environmental impacts. Moreover, NO3− and O3 production are highly correlated. Thus, a box model was employed to assess the effectiveness of concurrently reducing NOx and VOCs in mitigating both ozone and nitrate pollution, as demonstrated in Fig. 5I. Our earlier study revealed that a 9% annual decrease in VOCs (annual ΔVOCs = 9%) can effectively control the rise of O3 and OH/HO2 under the current NOx reduction (annual ΔNOx = 4.5%) in the YRD21. Figure 5I displays the average daily concentration of NO3− and the maximum O3 net production rate during pollution days from 2020 to 2030 when annual ΔVOCs/ΔNOx = 9%/4.5%. The results show a reduction of up to 30% in NO3− concentration and a 48% decrease in the maximum O3 net production rate in 2030 compared to 2020. These findings illustrate that the O3-targeting scheme could decrease both O3 and NO3− simultaneously.

In summary, this study explores the inherent relationship between the increase in nitrate NO3− and the elevation of surface O3 witnessed in winter in the YRD. Our analysis reveals that elevated nocturnal O3 levels catalyze N2O5 hydrolysis via chain reactions, subsequently enhancing the production of fine particulate NO3−. Moreover, the increasing levels of O3 and OH also accelerate NO2 + OH reaction (producing gas-phase HNO3). Under the environment rich in ammonia within the study area (Supplementary Fig. 3C), the produced gas-phase HNO3 is rapidly neutralized to NO3−. These results indicate that the effectiveness of prior NOx emission reduction strategies in diminishing winter NO3– pollution is compromised by increased O3 levels, stemming from complex nonlinear photochemical processes. Consequently, addressing the dual challenge of O3 and PM2.5 pollution in eastern China necessitates a synergistic approach to managing NOx and VOCs emissions, with an emphasis on VOC reduction. Our findings provide critical insights for designing effective strategies to mitigate O3 and PM2.5 pollution in comparable regions.

Methods

Observations

The monitoring station for this study was located in Xinjiangwancheng Street, Yangpu District, Shanghai (Supplementary Fig. 1). This area is surrounded by residential, commercial, educational, and health facilities, making it a representative location of the heavily populated urban center of Shanghai. The site is significantly affected by anthropogenic emissions of pollutants. The monitoring period for this study was from January 1, 2019, to February 28, 2019, with an hourly resolution. The concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 were measured using the Thermo Scientific FH62C14 series continuous particulate monitors, while the concentrations of SO2, NOx, CO, and O3 were measured using Thermo Scientific i-series SO2 analyzers, NO-NO2-NOx analyzers, CO analyzers, and O3 analyzers respectively. Temperature and relative humidity were measured using online monitoring equipment, while hourly wind speed and boundary layer height (BLH) data were obtained from ERA5 reanalysis products (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu).

The hourly concentrations of water-soluble inorganic ions (SO42−, NO3−, Cl−, NH4+, Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+) and the corresponding gas precursors (HCl, HNO3, and NH3) in the ambient air were determined by a model ADI 2080 online analyzer for Monitoring of AeRosols and GAses (MARGA, ApplikonAnalytical B.V. Corp., the Netherlands) with a PM2.5 cyclone. The hourly concentrations of 40 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were also monitored using an online gas chromatography analyzer (Focused Photonics, GC 955-615). Other gaseous Pollutants and VOC species are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2.

The data of routine air pollutants (PM2.5, NO2, O3) at ground level in the YRD were obtained from the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC). Monitoring data were collected using continuous automated equipment. All equipment passed the applicability test by the CNEMC, and all monitoring data were subjected to validity audits.

Observation-based model

The Observation-based model (OBM), a zero-dimensional box model, has been extensively used to simulate the chemical formation processes of NO3–, investigating atmospheric oxidative capacity and photochemistry. The observation-based model (OBM), a zero-dimensional box model, has been extensively used to simulate the chemical formation processes of NO3–, investigating atmospheric oxidative capacity and photochemistry34. This model identifies two principal pathways for NO3– formation: (I) gaseous HNO3 formation through the reaction of OH and NO2, followed by its reaction with NH3 to form particulate NO3– (Eqs. 6–7), and (II) the production of particulate NO3– via the simplified heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 (Eq. 8).

Equation (9) gives the rate for heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5, where \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) is the N2O5 uptake coefficient, \(\omega\) is the N2O5 mean molecular velocity (256 m s−1), \({S}_{a}\) is the aerosol surface area, and \(\varphi\) is the production yield of ClNO2. The uptake coefficient (\({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\)) is determined using an empirical parametric method proposed by Bertram and Thornton45. (Eq. 10), where A (3.2 × 10−8 s) is an empirical pre-factor and \({k}_{2f}\) is used to account for the H2O-limitation observed in the nitrate-free particles. The parameters \({k}_{3}/{k}_{2b}\) (=0.06) and \({k}_{4}/{k}_{2b}\) (=29) represent the relative rates of competing reactions of intermediate H2ONO+(aq) with H2O and Cl− over NO−, respectively46. \(\left[{{\rm{H}}}_{2}{\rm{O}}\right]\), \(\left[{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\right]\) and \(\left[{{{\rm{Cl}}}}^{-}\right]\) represent the aerosol water, nitrate and chloride molar concentrations, respectively, which are calculated using the thermodynamic model ISORROPIA II. \(\varphi\) is assumed to be 0.21 based on other winter studies47. It should be noted that other NO3− formation pathways make minor contributions to the NO3− concentration and are therefore not considered in this study48.

Apart from considering the sources of TNO3, this study takes into account the loss rate of TNO3. The loss rate coefficients (\({k}_{{{{\rm{HNO}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}{{\rm{dep}}}{{\rm{osition}}}}\)) for the gas-phase HNO3 and particle-phase NO3− during dry deposition are presented in Eqs. (11–12), where BLH denotes the boundary layer height obtained from ERA5 reanalysis data, and \({V}_{{{\rm{dep}}}}\) represents the deposition rate (cm s−1) based on research by Prabhakar et al.34. A crucial aspect of this model is the equilibrium between gas-phase HNO3 and particle-phase NO3–, with an assumption of 100% efficiency in the transfer from gas to particle phase. Prior studies indicate this assumption has minimal impact on model accuracy, particularly when NO3– comprises over 90% of TNO3 during winter34,49, a condition met in this study with NO3– making up 94.5% of TNO3 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

In addition to the discussed sources and sinks of NO3−, some studies have suggested that NO3− generated by nighttime chemical reactions within the mixing layer makes a significant contribution to surface NO3− through morning vertical transport, leading to a rapid increase in surface NO3− after sunrise (especially between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m.). Supplementary Fig. 7 showed a minor increase in surface NO3− in the morning in this study, but this increment was significantly less than in the other studies35,47. This may indicate that vertical transport has less effect on surface NO3– in our study. Gas-phase HNO3 exhibited a significant increase between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. likely due to the production of HNO3 facilitated by the sunrise. Consequently, this study excluded the contribution of vertical transport from the mixing layer.

This study constrained the model boundary using the on-site measurements of VOCs, O3, NO, NO2, SO2, CO, HONO, and meteorological parameters (temperature, humidity, etc.). The photodissociation rate data were obtained by combining the stratospheric UV and visible radiation code (TUV v5.3.1) with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 reanalysis data set and observational data. Additionally, Missing VOCs data points were interpolated from hourly values of the same day or from the nearest average values, with days missing more than three consecutive hours of data represented by the hourly average of the corresponding time period.

Given the inherent uncertainties in modeling results, study mainly focused on the atmospheric chemical situation before and after NO3− pollution, all pollution events were divided into three time periods: January 3, 2019 to January 16, 2019, January 8, 2019 to January 27, 2019, and February 13, 2020 to February 27, 2020. These time periods encompassed all pollution events, and each simulation of the time period began at 00:00 and was pre-run for seven days under the constraints of input data to ensure the unmeasured species in the sample reached a stable state.

To construct Fig. 5, we compiled hourly concentrations of PM2.5, NO2, and O3 from December 2018 to February 2019 for 314 Chinese cities. We identified polluted days (daily mean PM2.5 > 75 μg/m3) for each city, calculated pollutant levels for each pollution day and the 48-hour windows before and after, and aggregated these values across all cities. The final step involved summarizing the data for all 314 cities and illustrating the findings in Fig. 5.

ISORROPIA II model

The ISORROPIA II is a computationally efficient aerosol thermodynamic equilibrium model which has been extensively applied to calculate the chemical composition and phase state of an NH4+–SO42−–NO3−–Cl−-Na+–Ca2+–K+–Mg2+–H2O aerosol in thermodynamic equilibrium with the corresponding gas precursors. ISORROPIA II generally operates in two modes: (1) Forward mode, which requires input of temperature, relative humidity, and total concentrations of TNH3 (TNH3 = NH3 + NH4+), TNO3 (TNO3 = HNO3 + NO3−), TCl (TCl = HCl+Cl−), SO42−, Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+; and (2) Reverse mode, which requires inputs of temperature, relative humidity, and particle-phase concentrations of SO42−, NO3−, Cl−, NH4+, Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+. However, in actual simulation, the forward mode of ISORROPIA II predicts aerosol distribution and composition more accurately than the reverse mode. This is because the input of total concentrations of particle and gas phase effectively constrains measurement errors. For this analysis, the forward mode was selected, with an underlying assumption that the aerosol system remains in a metastable liquid state. Utilizing ISORROPIA II, we conducted evaluations on nitrate distribution across particle and gas phases, particle liquid water content, and the effects of NH3 emission reductions35,47,50.

Data availability

Meteorological data from ERA5 dataset are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu; hourly concentrations of PM2.5, NO2, and O3 for 314 Chinese cities are available at China National Environmental Monitoring Centre at https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/. Other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The underlying code of the OBM model for this study is available on the official website of the MCM mechanism and can be accessed via this link https://mcm.york.ac.uk/MCM/browse.

References

Sun, J. et al. Seasonal modeling analysis of nitrate formation pathways in Yangtze River Delta region, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 12629–12646 (2022).

Ding, A. et al. Significant reduction of PM2.5 in eastern China due to regional-scale emission control: evidence from SORPES in 2011–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 11791–11801 (2019).

Sun, W. et al. Chemistry-triggered events of PM2.5 explosive growth during late autumn and winter in Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 254, 112864 (2019).

Li, C., Hammer, M. S., Zheng, B. & Cohen, R. C. Accelerated reduction of air pollutants in China, 2017-2020. Sci. Total. Environ. 803, 150011 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Chinese regulations are working—why is surface ozone over industrialized areas still high? applying lessons from Northeast US air quality evolution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092816 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Decade-long trends in chemical component properties of PM2.5 in Beijing, China (2011−2020). Sci. Total. Environ. 832, 154664 (2022).

Zhou, M. et al. Elevated formation of particulate nitrate from N2O5 hydrolysis in the Yangtze River Delta Region From 2011 to 2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097393 (2022).

Shao, P. et al. Characterizing remarkable changes of severe haze events and chemical compositions in multi-size airborne particles (PM1, PM2.5 and PM10) from January 2013 to 2016–2017 winter in Beijing, China. Atmos. Environ. 189, 133–144 (2018).

Zhai, S. et al. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) trends in China, 2013–2018: separating contributions from anthropogenic emissions and meteorology. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 11031–11041 (2019).

Fu, Z. et al. Characteristics of aerosol chemistry and acidity in Shanghai after PM2.5 satisfied national guideline: Insight into future emission control. Sci. Total. Environ. 827, 154319 (2022).

Calvert, J. G. et al. Acid generation in the troposphere by gas-phase chemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17, 428A–443A (1983).

Petetin, H. et al. Assessing the ammonium nitrate formation regime in the Paris megacity and its representation in the CHIMERE model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 10419–10440 (2016).

Xue, J. et al. Insights into factors affecting nitrate in PM2.5 in a polluted high NOx environment through hourly observations and size distribution measurements. J. Geophys. Res.—Atmos. 119, 4888–4902 (2014).

Pathak, R. K. et al. Nighttime enhancement of PM2.5 nitrate in ammonia-poor atmospheric conditions in Beijing and Shanghai: Plausible contributions of heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 and HNO3 partitioning. Atmos. Environ. 45, 1183–1191 (2011).

Qu, Y. et al. The underlying mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 synergistic pollution in East China: photochemical and heterogeneous interactions. Sci. Total. Environ. 873, 162434 (2023).

Meng, Z. et al. Chemical coupling between atmospheric ozone and particulate matter. Science 277, 116–119 (1997).

Fu, X. et al. Persistent heavy winter nitrate pollution driven by increased photochemical oxidants in Northern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3881–3889 (2020).

Sun, P. et al. Two years of online measurement of fine particulate nitrate in the western Yangtze River Delta: influences of thermodynamics and N2O5 hydrolysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 17177–17190 (2018).

Nguyen, K. et al. NOx and VOC control and its effects on the formation of aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 36, 560–572 (2002).

Pun, B. K. et al. Sensitivity of particulate matter nitrate formation to precursor emissions in the California San Joaquin Valley. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 2979–2987 (2001).

Zhang, Z. et al. Attributing increases in ozone to accelerated oxidation of volatile organic compounds at reduced nitrogen oxides concentrations. PNAS Nexus 1, pgac266 (2022).

Zang, H. et al. High atmospheric oxidation capacity drives wintertime nitrate pollution in the eastern Yangtze River Delta of China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 4355–4374 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Diverse response of surface ozone to COVID-19 lockdown in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 789, 147739 (2021).

Zhai, T. et al. Elucidate the formation mechanism of particulate nitrate based on direct radical observations in the Yangtze River Delta summer 2019. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 2379–2391 (2023).

Duan, L. et al. Online measurement of PM2.5 at an air monitoring supersite in Yangtze River Delta: temporal variation and source identification. Atmosphere 11, 789 (2020).

Sun, P. et al. Impact of air transport and secondary formation on haze pollution in the Yangtze River Delta: In situ online observations in Shanghai and Nanjing. Atmos. Environ. 225, 117350 (2020).

Wang, H. L. et al. Chemical composition of PM2.5 and meteorological impact among three years in urban Shanghai, China. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 1302–1311 (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Source assessment of atmospheric fine particulate matter in a Chinese megacity: Insights from long-term, high-time resolution chemical composition measurements from Shanghai flagship monitoring supersite. Chemosphere 251, 126598 (2020).

Zhu, W. et al. Seasonal variation of aerosol compositions in Shanghai, China: Insights from particle aerosol mass spectrometer observations. Sci. Total. Environ. 771, 144948 (2021).

Javed, Z. et al. Spatiotemporal characterization of aerosols and trace gases over the Yangtze River Delta region, China: impact of trans-boundary pollution and meteorology. Environ. Sci. Eur. 34, 86 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Large scale control of surface ozone by relative humidity observed during warm seasons in China. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 3981–3989 (2021).

Qin, M. et al. PM2.5 and O3 relationships affected by the atmospheric oxidizing capacity in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 810, 152268 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Field determination of nitrate formation pathway in winter Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 9243–9253 (2020).

Prabhakar, G. et al. Observational assessment of the role of nocturnal residual-layer chemistry in determining daytime surface particulate nitrate concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 14747–14770 (2017).

Tan, Z. et al. An observational based modeling of the surface layer particulate nitrate in the north china plain during summertime. J. Geophys Res-Atmos. 126, e2021JD035623 (2021).

Vrekoussis, M. et al. Role of the NO3 radicals in oxidation processes in the eastern Mediterranean troposphere during the MINOS campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 4, 169–182 (2004).

Womack, C. C. et al. An odd oxygen framework for wintertime ammonium nitrate aerosol pollution in urban areas: NOx and VOC control as mitigation strategies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4971–4979 (2019).

Chen, T. et al. Volatile organic compounds and ozone air pollution in an oil production region in northern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 7069–7086 (2020).

Baasandorj, M. et al. Coupling between chemical and meteorological processes under persistent cold-air pool conditions: evolution of wintertime PM2.5 pollution events and N2O5 observations in Utah’s Salt Lake Valley. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5941–5950 (2017).

Ren, C. et al. Nonlinear response of nitrate to NOx reduction in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Atmos. Environ. 264, 118715 (2021).

Dang, R. et al. Quantifying the anthropogenic and meteorological influences on summertime surface ozone in China over 2012–2017. Sci. Total. Environ. 754, 142394 (2021).

Zhu, J. et al. Observationally constrained modeling of atmospheric oxidation capacity and photochemical reactivity in Shanghai, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 1217–1232 (2020).

Li, K. et al. A two-pollutant strategy for improving ozone and particulate air quality in China. Nat. Geosci. 12, 906–910 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. Ammonia emission control in China would mitigate haze pollution and nitrogen deposition, but worsen acid rain. PNAS 116, 7760–7765 (2019).

Bertram, T. H. et al. A. Toward a general parameterization of N2O5 reactivity on aqueous particles: the competing effects of particle liquid water, nitrate and chloride. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 8351–8363 (2009).

Yu, C. et al. Heterogeneous N2O5 reactions on atmospheric aerosols at four Chinese sites: improving model representation of uptake parameters. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 4367–4378 (2020).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. On the contribution of nocturnal heterogeneous reactive nitrogen chemistry to particulate matter formation during wintertime pollution events in Northern Utah. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 9287–9308 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. High N2O5 concentrations observed in urban Beijing: implications of a large nitrate formation pathway. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 416–420 (2017).

Franchin, A. et al. Airborne and ground-based observations of ammonium-nitrate-dominated aerosols in a shallow boundary layer during intense winter pollution episodes in northern Utah. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 17259–17276 (2018).

Weber, R. J. et al. High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years. Nat. Geosci. 9, 282–285 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22276038 and 42061134006), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [“Coupling and Abatement of atmospheric Ozone and PM in the Chinese Yangtse River Delta (PMO3)” under HE3086/46–1 and Project No. 448587068] and the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB2602001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Z.Z., B.L., X.L.; Formal analysis: C.L., X.M., J.J., H.H., J.C; Writing: Z.Z., B.L., X.L.; Supervision: X.L.; all authors contributed to discussing and improving the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Lu, B., Liu, C. et al. Nitrate pollution deterioration in winter driven by surface ozone increase. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 160 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00667-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00667-5

This article is cited by

-

Study on the source of nitrate in atmospheric particulate matter in Beijing using nitrogen and oxygen dual isotopes

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Effects of ozone pollution on crops and human health: evidence from the “2 + 36” cities of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and surrounding regions, China

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2025)

-

Intelligent Predictive Systems for Modeling PM10, Ozone, and Temperature Dynamics: A Forecasting Approach for Urban Air Quality in Delhi

Aerosol Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Ammonia-rich environment enhances nitrate formation in PM2.5 in a megacity of the Yangtze River Delta, China

Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry (2025)

-

The Hidden Dangers in the Rain: Human Health Risk Assessment of Fluoride and Nitrate in Rainwater from a Medium-Sized Industrial City

Water Conservation Science and Engineering (2024)