Abstract

Tree-based machine learning algorithms, such as random forest, have emerged as effective tools for estimating fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from satellite observations. However, they typically have unchanged model structures and configurations over time and space, and thus may not fully capture the spatiotemporal variations in the relationship between PM2.5 and predictors, resulting in limited accuracy. Here, we propose geographically and temporally weighted tree-based models (GTW-Tree) for remote sensing of surface PM2.5. Unlike traditional tree-based models, GTW-Tree models vary by time and space to simulate the variability in PM2.5 estimation, and they can output variable importance for every location for the deeper understanding of PM2.5 determinants. Experiments in China demonstrate that GTW-Tree models significantly outperform the conventional tree-based models with predictive error reduced by >21%. The GTW-Tree-derived time-location-specific variable importance reveals spatiotemporally varying impacts of predictors on PM2.5. Aerosol optical depth (AOD) contributes largely to PM2.5 estimation, particularly in central China. The proposed models are valuable for spatiotemporal modeling and interpretation of PM2.5 and other various fields of environmental remote sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution is a global environmental issue that impacts human health and climate change1,2,3,4. Satellites provide a means of wide-scale and high-frequency observations of Earth from space, offering a distinctive approach to mapping PM2.5 concentrations from regional to global scales5. With the ongoing development of ground monitoring networks worldwide, abundant data sources have created opportunities for data-driven machine learning-based remote sensing of PM2.56. The fundamental concept involves leveraging machine learning to discover the numerical relationship between satellite aerosol optical depth (AOD) and ground-level PM2.5, and conducting large-scale PM2.5 estimation based on the established relationship7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. This category of methods has been showing vigorous growth in recent years6,17.

Tree-based models, a highly significant category in machine learning18, have gained widespread popularity in PM2.5 remote sensing, such as Random Forest (RF)19,20,21, Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM)22,23,24, and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)25,26,27. These models possess nonlinear mapping and representation capabilities, effectively addressing the complex relationship between PM2.5 and predictors. They often outperform conventional statistical models, delivering superior accuracy in PM2.5 remote sensing. Additionally, tree-based models boast a significant advantage in their ability to conveniently output variable importance28, offering potential insights for research into the driving mechanisms of atmospheric PM2.529.

However, the relationships between PM2.5 and predictors vary temporally and spatially30,31. Existing tree-based algorithms typically serve as globally single models, which have unchanged model structures and configurations over space and time, and may not fully account for spatiotemporal variations. To be specific, different locations and times exhibit variations in pollution emissions, meteorological dispersion conditions, and topographical factors. For example, if it rains on a day in a certain area with severe PM2.5 pollution, rainfall becomes one of the dominant factors for PM2.532. However, this might not be the case at other times and areas. With a single global model, it may only capture the overall relationship between these variables and cannot model spatiotemporal variability. The input variables that can characterize such spatiotemporal differences need to be included (e.g., the start and duration of rainfall), otherwise, this could lead to reasonably accurate estimates on the whole, but less effective results for specific local regions33. Additionally, the variable importance provided by the global tree-based model is unchanged and perhaps cannot fully capture spatiotemporal differences in PM2.5 determinants.

To account for the spatiotemporal variations in PM2.5 remote sensing, an important type of research has attempted to integrate spatiotemporal information into machine learning models from a global modeling perspective, such as space-time random forest or extra-trees model12,34, geo-intelligent neural networks35, spatiotemporally weighted deep forest model36, and the four-dimensional space-time extra-trees model37. These models, compared to traditional machine learning models, are capable of enhancing the characterization of spatiotemporal changes, resulting in improved accuracy. Such models typically incorporate location and time information as input terms, thereby learning the implicit relationships in the temporal and spatial domains.

Besides, in geostatistics, there is a class of models specifically designed to address spatiotemporal variations, namely the classical geographically weighted regression (GWR)38 and its extensions, such as geographically and temporally weighted regression (GTWR)39. These models are locally constructed, meaning that a model is established individually at each location. They assign weights to the samples based on spatial and/or temporal distances within a local range, and these weights are incorporated into the modeling process. GWRs are a set of local linear models, so some research has drawn inspiration from GWR models to construct local tree-based models, aiming to conduct local nonlinear modeling. However, there are still some challenges: (1) These studies often do not incorporate sample weighting or adjust inputs through weights40,41,42, which might make it challenging to capture the spatiotemporal dependencies of samples. Furthermore, they frequently consider only spatial information, neglecting temporal dependencies43,44,45. (2) Local modeling may overly rely on local features46; when the characteristics of the target location are challenging to represent using local samples, it could lead to large modeling biases.

To this end, this study aims to develop geographically and temporally weighted tree-based models (GTW-Tree) to capture the spatiotemporal heterogeneity in PM2.5 remote sensing. These models are constructed using spatially and temporally local samples, and the weights of samples are introduced into model training. Furthermore, we enhance the model stability by additionally searching for similar non-local samples, allowing for incorporating global trends into local modeling. This study uses three typical tree-based algorithms to construct GTW-Tree models, namely GTW-RF, GTW-LGBM, and GTW-XGBoost. The contributions could be summarized into the following aspects. First, we propose GTW-Tree models to obtain spatially continuous PM2.5 estimates with higher accuracy. Second, the in-depth exploration of the spatiotemporal changes in the variable importance of PM2.5 modeling potentially helps enhance our understanding of the driving mechanisms. Our models exhibit strong applicability and can be extended to spatiotemporal modeling for other various fields of environmental research.

Results

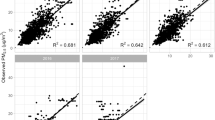

Predictive performance

This study randomly selects spatially independent grid cells containing monitoring sites as the validation and test sets. The validation set would involve model parameter selection. The model adjusts its parameters based on the performance of the validation set, aiming to enhance its generalization. The validation set helps prevent the model from overfitting, while also enabling the selection of the optimal model. The test set is entirely independent of evaluating the model performance. The evaluation metrics include the coefficient of determination (R2), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and relative prediction error (RPE), and the details can be found in Supplementary Note 1. The results are presented in Fig. 1. RF performs the best among the three global models. The validation and test R2 (RMSE) for RF are 0.772 (15.45 μg m−3) and 0.796 (15.76 μg m−3), respectively. On the other hand, the LGBM and XGBoost models show poorer performance, with LGBM achieving a validation and test R2 (RMSE) of 0.660 (18.81 μg m−3) and 0.673 (19.85 μg m−3), respectively. XGBoost obtains an R2 of 0.678 and 0.690, along with RMSE values of 18.29 and 19.30 μg m−3 on the validation and test sets, respectively. Overall, the performance of the global models is somewhat disappointing, especially for LGBM and XGBoost, indicating that they do not accurately model the relationship between PM2.5 and predictors.

The dotted line is the 1:1 line, and N is the number of samples. “Val” and “Test” represent model validation and test, respectively. Each subplot is labeled with a combination of letters and numbers, where a, b, and c respectively refer to RF/GTW-RF, LGBM/GTW-LGBM, XGBoost/GTW-XGBoost, and the numbers 1–4 refer to the validation and test results of the global models and local models, respectively. The equations stand for the regression relationships between the estimated and observed PM2.5.

Compared to the global models, the GTW-Tree models achieve improved accuracy by considering spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Transitioning from the global RF to the GTW-RF model, the validation (test) R2 increases from 0.772 (0.796) to 0.858 (0.881), and RMSE decreases from 15.45 μg m−3 (15.76 μg m−3) to 12.14 μg m−3 (12.00 μg m−3). GTW-LGBM and GTW-XGBoost models exhibit even more substantial improvements in performance. The validation R2 improves by 0.197 (from 0.660 to 0.857), and RMSE decreases by 6.59 μg m−3 (from 18.81 to 12.22 μg m−3) from LGBM to GTW-LGBM, and the test R2 increases by 0.192 (from 0.673 to 0.865), and RMSE decreases by 7.09 μg m−3 (from 19.85 to 12.76 μg m−3). As for GTW-XGBoost, the validation/test R2 improved by 0.169 (from 0.678 to 0.847)/0.187 (from 0.690 to 0.877). The reduction in test RMSE is particularly significant, at around 37% (from 19.30 to 12.18 μg m−3). On average, transitioning from global tree-based models to GTW-Tree models results in a mean decrease of 30.6% in RMSE. The primary reason for the improvement in modeling accuracy is that compared with global tree-based models, GTW-Tree models fully simulate the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the relationship between PM2.5 and influencing factors, resulting in stronger spatiotemporal extrapolation ability. Furthermore, the issue of underestimating high PM2.5 values is a common challenge in this field11,47,48. This problem is particularly pronounced in global models, possibly due to constructing a single global model with fewer high-value samples. Fortunately, GTW-Tree models have proven effective in mitigating this issue. One potential explanation is that GTW-Tree models are constructed within local environments, where the variations in PM2.5 are relatively minor (high-value regions generally have high levels of PM2.5 in their surroundings), thus modeling with local samples facilitates the capture of high-value PM2.5. In summary, the local GTW-Tree models consistently outperform the global models, where GTW-RF exhibited relatively modest improvements, and GTW-LGBM and GTW-XGBoost show significant enhancements.

Furthermore, we compare the model performance at the grid cell scale, as shown in Fig. 2, which indicates that GTW-Tree models work better than the global models. On the validation set, 89.3, 91.7, and 89.3% of the grid cells achieve better accuracy for GTW-RF, GTW-LGBM, and GTW-XGBoost, respectively. On the other hand, the proportions are 90.2, 91.3, and 91.3% on the test set. Spatially, GTW-Tree models perform significantly better in the central and eastern regions of China, where ground stations are more densely distributed, aiding the capture of local features. Notably, GTW-Tree models do not report a distinct advantage in western China, compared to the global models, due to the sparsity of monitoring sites.

In addition, we also compare the model performance on a daily scale. Supplementary Fig. 1 presents the results for four days in 2019: March 1, June 1, September 2, and December 1. The results indicate that GTW-Tree models show better performance than the global models for each day. It is worth noting that while the global models generally work well (e.g., RF test R2 = 0.796), their performance for single-day estimations is less satisfactory, with test R2 values of 0.76, 0.44, 0.68, and 0.51 for the RF model on the four days. In contrast, GTW-RF achieves R2 values of 0.91, 0.72, 0.82, and 0.61 on the same days, showing superior performance in local estimations.

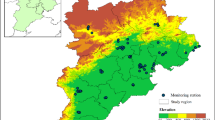

Spatiotemporal variation in remote sensing modeling of PM2.5

The GTW-Tree models outshine the global models due to the consideration of the spatiotemporal variations. To delve deeper, we conduct a quantitative analysis. The variable importance provided by the global RF, LGBM, and XGBoost is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, which offers variable importance from an overall view, i.e., it is a result that considers all locations and times as a whole. For the RF model, the three most important variables are CAMS-PM2.5, T, and AOD, while the least important variables are UW and VW. The importance of these variables remains consistent throughout the entire year nationwide, indicating that the global RF model fails to capture spatiotemporal variations, consequently limiting the modeling accuracy. In reality, the variable importance varies in time and space. Based on the proposed GTW-RF model, we explore the variations in variable importance across time and space, as shown in Fig. 3. Different regions exhibit varying results in variable importance, which is more refined compared to the global RF outcomes. This is beneficial for understanding the diversity in driving mechanisms of PM2.5. AOD is generally an important factor in the central regions of China. This may be related to factors such as aerosol types and meteorological conditions49,50. Meteorological variables and reanalysis data are more critical for the coastal areas. We are all aware that AOD is the most commonly utilized proxy variable in PM2.5 remote sensing. A more detailed analysis of the significance of AOD is outlined in Fig. 3b. In general, AOD ranks relatively high in many regions, especially in central China, which is possibly a result of the strong AOD-PM2.5 relationship. AOD is not ranked as the predominant contributor in southern China and coastal regions, which might be related to the meteorological conditions of high humidity51. Under high humidity conditions, the hygroscopic effect of aerosol increases the extinction efficiency, resulting in larger AOD values. However, PM2.5 measurements are less influenced by humidity, leading to a weaker correlation between AOD and PM2.5.

Simultaneously, we take December 1, 2019, as an example for mapping and analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The GTW-RF estimates exhibit a high degree of consistency with ground station measurements, as depicted in Fig. 4a, b. Figure 4c displays the spatial distribution of modeling sample numbers, with areas characterized by sparse station distribution having a greater number of modeling samples. Conversely, regions with densely distributed stations exhibit relatively fewer samples, primarily in eastern China. The spatial distribution of sample numbers is smooth, underscoring that the weighting function and sample selection strategy ensure the smoothness of the spatial mapping of PM2.5 concentrations, as observed in Fig. 4a. Figure 4d illustrates the distribution of the most important variables, highlighting the spatial heterogeneity. We chose two regions for in-depth analysis. The first one, referred to as region #A, is where NO2 stands as the most pivotal variable, reported by GTW-RF modeling. The PM2.5-AOD and PM2.5-NO2 relationships for region #A on December 1 are investigated, and the results indicate a more significant relationship exists in PM2.5 and NO2 (Fig. 4e), in line with GTW-RF results. The other is region #B, where AOD is predominantly important, except for the inner region #C. We examine the AOD-PM2.5 relationship for region #C and the rest of region #B. There is indeed no significant AOD-PM2.5 relationship within region #C, while the rest of region #B exhibits a high correlation (Fig. 4f). These analyses reveal that the GTW-RF model effectively captures spatiotemporal variability in remote sensing modeling of PM2.5, leading to superior estimation accuracy, and providing additional possibilities for the study of the spatiotemporal differences in PM2.5 driving factors. Similar to existing research37, we can also provide a more detailed understanding of variable importance, bringing the potential for deeply exploring PM2.5 driving mechanisms. Explainable artificial intelligence (AI) is currently a crucial trend, and our research, along with others in the field, collectively promotes the development of explainable AI.

a Estimated PM2.5 concentrations across China; b PM2.5 measurements of ground sites; c Number of training samples for each location; d Distribution of the most important variable, 1–8 represent AOD, PS, UW, VW, T, HCHO, NO2, and CAMS-PM2.5; e AOD-PM2.5 and NO2-PM2.5 relationships within region #A; f AOD-PM2.5 relationships within region #B (except for region #C) and region #C. r stands for correlation coefficient, * and *** means the 95% and 99.9% confidence level, respectively.

Discussion

Local modeling can comprehensively simulate spatiotemporal heterogeneity, but it may have limitations in heavily relying on local features52, which can lead to suboptimal estimates when there are significant differences in local characteristics. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3, we consider the encircled location as the target point. It exhibits lower PM2.5 concentrations compared to the surrounding modeling points, but with little variation in the input variables. This suggests that it represents an “anomalous” point and is likely to be overestimated. To address this issue, we search for non-local samples to incorporate into the modeling process, which represents the global trends to some extent. Compared to the models without non-local samples (see Supplementary Fig. 4), adding the non-local modeling strategy improves the test accuracy (GTW-RF test R2 from 0.865 to 0.881). Is the inclusion of the non-local modeling strategy suitable for all scenarios? It primarily depends on whether it can alleviate extreme variations like the above one discussed. The non-local modeling strategy is an optional choice for GTW-Tree modeling, and it may not universally improve accuracy in all cases. Here, we provide a potential modeling approach for situations with significant local variations. Indeed, the proposed GTW-Tree models demonstrate substantial improvements over traditional global models, regardless of whether the non-local modeling strategy is included or not.

The motivation for spatiotemporal weighting is to assign different weights to samples based on their distances relative to the target location39,53. In reality, it is possible to perform local modeling without weighting, where all samples have equal weight (i.e., a weight of 1). We summarize the necessity of spatiotemporal weighting from two perspectives: First, in terms of accuracy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the results experience a slight decrease in accuracy when no weighting is applied, although this decrease is not substantial. Second, regarding the spatial smoothness of PM2.5 estimates, the mapping result can become less smooth without spatiotemporal weighting, as found in Supplementary Fig. 6. Therefore, it can be concluded that spatiotemporal weighting is necessary, and we construct GTW-Tree models rather than the simple local ones.

The GTW-Tree model has been compared with our previously proposed geographically and temporally weighted neural network (GTWNN) model33, and this study demonstrates similar modeling accuracy. GTWNN obtains the validation performance of R2 = 0.871 and RMSE = 11.61 μg m−3, and its test performance is R2 = 0.862 and RMSE = 12.85 μg m−3. This study introduces three distinct aspects compared to the previous study33. First, unlike NN, tree-based models are easier to train and solve, thus not requiring guidance and constraints from a global model as in the previous study33. Second, tree-based models offer the advantage of conveniently outputting variable importance, which can be utilized to investigate the spatiotemporal differences in factors determining PM2.5. Third, this study introduces a non-local modeling strategy, potentially further enhancing the modeling stability.

The advantages of GTW-Tree modeling lie in capturing spatiotemporal heterogeneity for enhanced accuracy and obtaining variable importance at each location. However, there are also uncertainties and limitations. Firstly, local modeling significantly increases computational demands compared to global models, in this study, the training time for RF and GTW-RF models on the training set containing 315,846 samples are 3.77 min and 76.92 min (on the Intel Core i7-10700K CPU), respectively. How to improve computational efficiency remains a challenge54. Here, we have tried to improve computational efficiency by utilizing multi-thread parallel computing. Furthermore, integrating the local GTW-Tree models with a global model may be a promising idea. The spatial distribution of monitoring sites is an important factor influencing the modeling accuracy of global and local models. Existing studies can be referenced to calculate the density of monitoring sites within the study area44, and then decide whether to use a global or local model. Subsequently, a fusion strategy could be constructed to merge the results of the global and local models, thereby achieving higher accuracy than the global model and greater efficiency than the local model. Secondly, GTW-Tree modeling has certain requirements regarding station density. In regions with sparse station distribution, such as western China, it may not necessarily outperform global models (see Fig. 2). In addition, this study mainly focuses on whether the GTW-Tree models can enhance modeling accuracy and interpretability by considering spatiotemporal heterogeneity. However, compared to existing research34,55, our study has fewer input variables, for instance, neither land use/land cover nor socioeconomic information is introduced, and this issue should be further explored. Lastly, the comparison between the global models and the GTW-Tree models may be somewhat unfair, as the global models do not incorporate spatiotemporal information. Therefore, we have introduced spatiotemporal information into the global models, leading to a noticeable improvement in performance, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. However, the global models still exhibit lower accuracy compared to the GTW-Tree models. Additionally, the GTW-Tree models are capable of generating finer variable importance, accentuating their advantages over the global models.

Methods

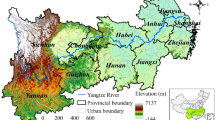

Data collection

This study is carried out in China for the year 2019, and it employs four categories of data: (1) Ground-level PM2.5 data, comprising hourly data from approximately 1600 monitoring sites across China, from which daily averages are calculated for modeling. (2) Satellite AOD data. AOD is the most commonly used proxy variable for PM2.5 remote sensing. We adopt daily seamless AOD products generated by a previous study10, which takes MODIS AOD derived using the Multi-Angle Implementation of Atmospheric Correction (MAIAC) algorithm56 as the baseline data. (3) ERA5 [Fifth Generation of ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) Reanalysis] meteorological variables57. Many studies have shown meteorological variables contribute to the improvement of PM2.5 remote sensing6,58, and here, we use surface pressure (PS), 10-m U/V wind (UW and VW), and 2-m temperature (T). (4) CAMS (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service) reanalysis data59. Atmospheric model outputs are often used to complement PM2.5 remote sensing modeling, and we include precursors of PM2.5, such as formaldehyde (HCHO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and PM2.5 reanalysis (CAMS-PM2.5). Detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

The grid cells containing monitoring sites are randomly partitioned into training (80%), validation (10%), and test sets (10%), as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7. It is important to note that in this study, the training, validation, and testing sets are spatially independent. This choice aligns with the primary objective of spatial expansion of PM2.5 monitoring, namely, transitioning from site-specific observations to spatially continuous mapping. Presently, multiple validation approaches have been employed60, including assessing the predictive performance for PM2.5 beyond the modeling period. However, this aspect is not the primary focus of our research. During the process of modeling and mapping of PM2.5, a 0.1° resolution of grid is adopted. Measurements from multiple monitoring sites located in one grid cell are averaged. Satellite, ERA5, and CAMS datasets are resampled to 0.1° resolution. After spatiotemporal alignment, a total of 315,846 records are collected for modeling.

GTW-Tree modeling

GTW-Tree deals with spatiotemporal heterogeneity through a local modeling strategy, which involves constructing a separate model for each target location and utilizing local samples for model training, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The mathematical expression of the model for each location (μi, vi, ti) is:

Where (μi, vi, ti) denotes the coordinates of the i-th location, and μ, v, and t stand for longitude, latitude, and time (day), respectively. y means PM2.5 concentration, and x represents input predictors, including MODIS AOD, ERA5 meteorological variables, and CAMS reanalysis data. Here, \({{MODEL}}_{({\mu }_{i},{v}_{i},{t}_{i})}()\) represents tree-based model designed explicitly for the ith location, whose specific implementations include RF, LGBM, and XGBoost (referring to Supplementary Note 2 for model descriptions). That is, the constructed GTW-Tree models are GTW-RF, GTW-LGBM, and GTW-XGBoost. Simultaneously, based on the set of tree-based models, it is possible to obtain the variable importance for each spatiotemporal location61, revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of PM2.5 dominating factors.

The three-dimensional coordinate system represents latitude, longitude, and time (day). At each time point, we have satellite AOD, ERA5 data, CAMS data, and ground PM2.5 data. For each spatiotemporal location (μi, vi, ti), a tree-based model, i.e.,\({\mathrm{MODEL}}_{({\mu }_{i},{v}_{i},{t}_{i})}\), is built, and local samples and non-local samples are used to train it.

We train the model using samples within the local context (only the samples before the target time, i.e., t ≤ ti). It is assumed that samples closer to the target location have larger weights, similar to previous studies39,62. We calculate the weight of each sample using a Gaussian function, as depicted in Supplementary Note 3. After obtaining the sample weights \({\bf{W}}={({w}_{1}\cdots {w}_{k}\cdots {w}_{n})}^{T}\) (n is the number of samples), we incorporate these weights into model training. Model construction is carried out using the scikit-learn package and API (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/)63, and the weights are applied to the fit function, i.e., MODEL.fit (X, Y, W), where X and Y represent the matrix of input predictors and PM2.5, respectively. The sample weights affect the tree splitting and gradient optimization, and those with larger weights contribute more to modeling (see Supplementary Note 4). It is worth noting that local modeling leads to significantly increased computational complexity, and we employ a multi-threading parallel computing strategy to improve computational efficiency. The parameters of the model can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

The GTW-Tree models have been constructed for PM2.5 remote sensing through the above process. However, there are scenarios where the performance might not be optimal because the local modeling approach relies heavily on local characteristics. For a straightforward example, when the target location actually has low concentrations, but the local surroundings exhibit high values, leading to overestimation. Here, we additionally introduce a non-local modeling strategy, which searches for global similar samples before the time of ti. Local modeling refers to training based on spatiotemporal neighboring samples, while “non-local” modeling means including similar samples across the entire global context, rather than within a limited spatiotemporal vicinity, and the similarity for samples is defined as:

Where xi means input predictors of target location, xm indicates the input variables of sample m within the search space, and k represents the kth input variable. The smaller S, the more similar it is. We identify the Ns most similar samples (Ns is set to 3) and incorporate them into the model training to introduce global trends, with their weights determined as the maximum value of the aforementioned W. Note that the samples selected in this process may be the same as those local ones. However, this is not an issue and demonstrates that these samples should be included in the modeling from both local and global perspectives.

Data availability

Ground-level PM2.5 data were available at the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/). Satellite AOD data can be obtained at https://zenodo.org/record/5652257#.YrPHW3ZBybg. ERA5 meteorological data were available at the Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form), CAMS reanalysis data were available from the Atmosphere Data Store of CAMS (https://ads.atmosphere.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/cams-global-reanalysis-eac4?tab=form), and the specific variables can be found in the Data Collection section.

Code availability

Codes are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (litw8@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

References

Li, C. et al. Reversal of trends in global fine particulate matter air pollution. Nat. Commun. 14, 5349 (2023).

Xu, F. et al. The challenge of population aging for mitigating deaths from PM2.5 air pollution in China. Nat. Commun. 14, 5222 (2023).

Geng, G. et al. Drivers of PM2.5 air pollution deaths in China 2002–2017. Nat. Geosci. 14, 645–650 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Transboundary health impacts of transported global air pollution and international trade. Nature 543, 705–709 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Satellite remote sensing of atmospheric particulate matter mass concentration: advances, challenges, and perspectives. Fundamental Res. 1, 240–258 (2021).

Bai, K. et al. Global synthesis of two decades of research on improving PM2.5 estimation models from remote sensing and data science perspectives. Earth Sci. Rev. 241, 104461 (2023).

Jin, C., Yuan, Q., Li, T., Wang, Y. & Zhang, L. An optimized semi-empirical physical approach for satellite-based PM2.5 retrieval: embedding machine learning to simulate complex physical parameters. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 4137–4154 (2023).

Li, T., Yang, Q., Wang, Y. & Wu, J. Joint estimation of PM2.5 and O3 over China using a knowledge-informed neural network. Geosci. Front. 14, 101499 (2023).

Yan, X., Zang, Z., Luo, N., Jiang, Y. & Li, Z. New interpretable deep learning model to monitor real-time PM2.5 concentrations from satellite data. Environ. Int. 144, 106060 (2020).

Bai, K. et al. LGHAP: the long-term gap-free high-resolution air pollutant concentration dataset, derived via tensor-flow-based multimodal data fusion. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 907–927 (2022).

Geng, G. et al. Tracking air pollution in China: near real-time PM2.5 retrievals from multisource data fusion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12106–12115 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Estimating 1-km-resolution PM2.5 concentrations across China using the space-time random forest approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111221 (2019).

Li, T., Shen, H., Zeng, C., Yuan, Q. & Zhang, L. Point-surface fusion of station measurements and satellite observations for mapping PM2.5 distribution in China: methods and assessment. Atmos. Environ. 152, 477–489 (2017).

Ma, Z., Hu, X., Huang, L., Bi, J. & Liu, Y. Estimating ground-level PM2.5 in China using satellite remote sensing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7436–7444 (2014).

Hoff, R. M. & Christopher, S. A. Remote sensing of particulate pollution from space: have we reached the promised land? J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 59, 645–675 (2009).

Martin, R. V. Satellite remote sensing of surface air quality. Atmos. Environ. 42, 7823–7843 (2008).

Ma, Z. et al. A review of statistical methods used for developing large-scale and long-term PM2.5 models from satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 269, 112827 (2022).

Pichler, M. & Hartig, F. Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 994–1016 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Estimating the daily PM2.5 concentration in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region using a random forest model with a 0.01°×0.01° spatial resolution. Environ. Int. 134, 105297 (2020).

Brokamp, C., Jandarov, R., Hossain, M. & Ryan, P. Predicting daily urban fine particulate matter concentrations using a random forest model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4173–4179 (2018).

Wongnakae, P., Chitchum, P., Sripramong, R. & Phosri, A. Application of satellite remote sensing data and random forest approach to estimate ground-level PM2.5 concentration in Northern region of Thailand. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 30, 88905–88917 (2023).

Choi, H., Park, S., Kang, Y., Im, J. & Song, S. Retrieval of hourly PM2.5 using top-of-atmosphere reflectance from geostationary ocean color imagers I and II. Environ. Pollut. 323, 121169 (2023).

Yang, Q., Yuan, Q. & Li, T. Ultrahigh-resolution PM2.5 estimation from top-of-atmosphere reflectance with machine learning: theories, methods, and applications. Environ. Pollut. 306, 119347 (2022).

Wang, Y., Yuan, Q., Li, T., Tan, S. & Zhang, L. Full-coverage spatiotemporal mapping of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 over China from Sentinel-5P and assimilated datasets: considering the precursors and chemical compositions. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148535 (2021).

Just, A. C. et al. Advancing methodologies for applying machine learning and evaluating spatiotemporal models of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) using satellite data over large regions. Atmos. Environ. 239, 117649 (2020).

Zamani Joharestani, M., Cao, C., Ni, X., Bashir, B. & Talebiesfandarani, S. PM2.5 prediction based on random forest, XGBoost, and deep learning using multisource remote sensing data. Atmosphere 10, 373 (2019).

Chen, Z.-Y. et al. Extreme gradient boosting model to estimate PM2.5 concentrations with missing-filled satellite data in China. Atmos. Environ. 202, 180–189 (2019).

Hu, X. et al. Estimating PM2.5 concentrations in the conterminous United States using the random forest approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6936–6944 (2017).

Su, Z., Lin, L., Chen, Y. & Hu, H. Understanding the distribution and drivers of PM2.5 concentrations in the Yangtze River Delta from 2015 to 2020 using Random Forest Regression. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 284 (2022).

Yang, Q., Yuan, Q., Yue, L. & Li, T. Investigation of the spatially varying relationships of PM2.5 with meteorology, topography, and emissions over China in 2015 by using modified geographically weighted regression. Environ. Pollut. 262, 114257 (2020).

Tai, A. P. K., Mickley, L. J. & Jacob, D. J. Correlations between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and meteorological variables in the United States: Implications for the sensitivity of PM2.5 to climate change. Atmos. Environ. 44, 3976–3984 (2010).

Fang, X., Zou, B., Liu, X., Sternberg, T. & Zhai, L. Satellite-based ground PM2.5 estimation using timely structure adaptive modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 186, 152–163 (2016).

Li, T., Shen, H., Yuan, Q. & Zhang, L. A locally weighted neural network constrained by global training for remote sensing estimation of PM2.5. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens. Environ. 252, 112136 (2021).

Li, T., Shen, H., Yuan, Q., Zhang, X. & Zhang, L. Estimating ground-level PM2.5 by fusing satellite and station observations: a geo-intelligent deep learning approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11,985–911,993 (2017).

Wei, J. et al. Ground-level NO2 surveillance from space across China for high resolution using interpretable spatiotemporally weighted artificial intelligence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9988–9998 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. First close insight into global daily gapless 1 km PM2.5 pollution, variability, and health impact. Nat. Commun. 14, 8349 (2023).

Fotheringham, A. S., Charlton, M. E. & Brunsdon, C. Geographically weighted regression: a natural evolution of the expansion method for spatial data analysis. Environ. Plann. A 30, 1905–1927 (1998).

Huang, B., Wu, B. & Barry, M. Geographically and temporally weighted regression for modeling spatio-temporal variation in house prices. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24, 383–401 (2010).

Georganos, S. et al. Geographical random forests: a spatial extension of the random forest algorithm to address spatial heterogeneity in remote sensing and population modelling. Geocarto Int. 36, 121–136 (2021).

Santos, F., Graw, V. & Bonilla, S. A geographically weighted random forest approach for evaluate forest change drivers in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. PLoS ONE 14, e0226224 (2019).

Su, Z. et al. Modeling the effects of drivers on PM2.5 in the Yangtze River Delta with geographically weighted Random Forest. Remote Sens. 15, 3826 (2023).

Ye, M. et al. Estimation of the soil arsenic concentration using a geographically weighted XGBoost model based on hyperspectral data. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159798 (2023).

Wang, Y., Yuan, Q., Zhu, L. & Zhang, L. Spatiotemporal estimation of hourly 2-km ground-level ozone over China based on Himawari-8 using a self-adaptive geospatially local model. Geosci. Front. 13, 101286 (2022).

Fan, Z., Zhan, Q., Yang, C., Liu, H. & Bilal, M. Estimating PM2.5 concentrations using spatially local Xgboost based on full-covered SARA AOD at the urban scale. Remote Sens. 12, 3368 (2020).

Fotheringham, A. S., Yang, W. & Kang, W. Multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR). Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 107, 1247–1265 (2017).

Yin, S., Li, T., Cheng, X. & Wu, J. Remote sensing estimation of surface PM2.5 concentrations using a deep learning model improved by data augmentation and a particle size constraint. Atmos. Environ. 287, 119282 (2022).

Xiao, Q. et al. Separating emission and meteorological contributions to long-term PM2.5 trends over eastern China during 2000–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 9475–9496 (2021).

Yang, Q. et al. The relationships between PM2.5 and aerosol optical depth (AOD) in mainland China: About and behind the spatio-temporal variations. Environ. Pollut. 248, 526–535 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Influence of meteorological conditions on PM2.5 concentrations across China: a review of methodology and mechanism. Environ. Int. 139, 105558 (2020).

Xin, J. et al. The observation-based relationships between PM2.5 and AOD over China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 10,701–710,716 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. A mixed geographically and temporally weighted regression: exploring spatial-temporal variations from global and local perspectives. Entropy 19, 53 (2017).

He, Q. & Huang, B. Satellite-based high-resolution PM2.5 estimation over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China using an improved geographically and temporally weighted regression model. Environ. Pollut. 236, 1027–1037 (2018).

Li, Z., Fotheringham, A. S., Li, W. & Oshan, T. Fast geographically weighted regression (FastGWR): a scalable algorithm to investigate spatial process heterogeneity in millions of observations. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 33, 155–175 (2019).

Xue, T. et al. Spatiotemporal continuous estimates of PM2.5 concentrations in China, 2000–2016: a machine learning method with inputs from satellites, chemical transport model, and ground observations. Environ. Int. 123, 345–357 (2019).

Lyapustin, A., Wang, Y., Korkin, S. & Huang, D. MODIS collection 6 MAIAC algorithm. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 5741–5765 (2018).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Chelani, A. B. Estimating PM2.5 concentration from satellite derived aerosol optical depth and meteorological variables using a combination model. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 10, 847–857 (2019).

Inness, A. et al. The CAMS reanalysis of atmospheric composition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 3515–3556 (2019).

Li, T., Shen, H., Zeng, C. & Yuan, Q. A validation approach considering the uneven distribution of ground stations for satellite-based PM2.5 estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 13, 1312–1321 (2020).

Gregorutti, B., Michel, B. & Saint-Pierre, P. Correlation and variable importance in random forests. Stat. Comput. 27, 659–678 (2017).

Li, T., Shen, H., Yuan, Q. & Zhang, L. Geographically and temporally weighted neural networks for satellite-based mapping of ground-level PM2.5. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 167, 178–188 (2020).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42201359) and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2022A1515010492).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, revision, reviewing, editing, and resources. Y.W.: Writing—original draft preparation, revision, reviewing, and editing. J.W.: Writing—original draft preparation, revision, reviewing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Wang, Y. & Wu, J. Deriving PM2.5 from satellite observations with spatiotemporally weighted tree-based algorithms: enhancing modeling accuracy and interpretability. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 138 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00692-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00692-4