Abstract

The analysis reveals that the occurrence of summer Monsoon Depressions (MDs) over the North Arabian Sea is doubling during 2001–2022 compared to the 1981–2000 period. This increase stems from changes in the region’s dynamic and thermodynamic conditions. The heightened genesis potential parameter with sea surface temperature and moisture flux transport and its convergence over the North Arabian Sea inducing MDs formation, contrasting to the Bay of Bengal. The dynamic processes involved in its formation, a combination of barotropic and dynamical instability, are leading to increased rainfall over northwestern India. Strong East Asian jet variability, with an anomalous anticyclone in the north and weak cyclonic anomalies in the south, induces prevailing easterly wind anomalies along the monsoon trough. This leads to a poleward shift (~1.13°) in the low-level jet, significantly altering dynamic and thermodynamic parameters in the northern Arabian Sea region leading to a notable increase in MDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interconnection between the Indian economy, agricultural production, and the Indian summer monsoon (ISM) rainfall is a well-acknowledged fact, with even slight deviations in monsoon intensity would have far-reaching consequences1,2. This intricate phenomenon, exacerbated by global warming and internal variability, thereby changing the nature of ISM rainfall3,4 and presents inherent challenges. In recent decades, the spatial distribution of rainfall over India exhibits a dipole pattern, with excess rainfall over northwestern regions5,6,7,8,9, and a deficit in Indo-Gangetic plains (IGP)10. The lives and livelihoods of millions dwelling across the IGP are profoundly affected by this behavior of dipole pattern of monsoon rainfall over India with extreme floods and droughts10,11,12. This has emerged as a pivotal subject within the monsoon research community. Recent research conducted by Singh et al.7 has found that the rising pressure over the Tibetan Plateau plays a pivotal role in increasing ISM rainfall over northwestern India (NWI). This revelation is further fortified by the findings of Mahendra et al.8, who astutely attribute this transformative shift to the phase alteration of mid-latitude circulation patterns known as Silk Road Pattern (SRP), which is an important zonally oriented teleconnection pattern in the boreal summer13,14. Previous studies strongly confirm a significant link between changes in atmospheric circulation over the Tibetan Plateau and their profound impact on the monsoon rainfall in NWI7,8,15. In addition, prior studies have well-documented and established links between variations in ISM rainfall regionally and country-wide, with ocean-atmosphere processes16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, the causes of the increase in rainfall over NWI remain in potential research. Indeed, new physical mechanisms are emerging in understanding the changes in the monsoon dynamics. Even though, the debate surrounding the ISM rainfall dipole pattern remains unresolved to this day.

One of the notable components in understanding ISM dynamics is the movement of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ)25,26,27 and the formation of synoptic-scale disturbances28,29 known as monsoon depressions (MDs). These systems, responsible for a significant portion of monsoon rains, exhibit features of cyclonic circulation spanning thousands of km horizontally, with heights reaching 6–9 km28,30,31,32,33. Thereby, providing plentiful rainfall, especially over the southwestern section of the system. However, recent studies have indicated a decline in MDs frequency over the Bay of Bengal (BoB)9,34,35,36, while others have observed an increase in short-lived low-pressure systems and the number of dry days37,38,39, aligning with negative rainfall trends in northern parts of central India/IGP5,8,9,10. The weakening of barotropic instability over the head BoB region may be contributing to the declining trend in MDs along with reduced mid-tropospheric relative humidity in recent decades9,35,36,40. Furthermore, these systems exhibit a cold core with a warm core aloft, and due to substantial vertical wind shear during the southwest monsoon season, they often do not develop into cyclones30,31,33,41,42. In contrast, there has been an increase in cyclonic activity over the Arabian Sea, attributed to rising sea surface temperatures (SST) driven by global warming43,44,45,46,47,48,49. This shift is altering the traditional pattern50, with the Arabian Sea now experiencing more cyclones compared to the BoB off India’s eastern coast during pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons46,47,48,49. Baburaj et al.48 found increasing Arabian Sea cyclones during the monsoon onset phase, thereby altering the Kinetic Energy of monsoon circulation and vertical wind shear due to the presence of cyclones in recent years.

In addition to that, IPCC 4th Assessment Report: projections showed a likely westward shift in the rainfall pattern by the end of the century 60% of Coupled models agree with this (www.ipcc.ch/). This is happening faster than even the most climate scientists expected. In recent years, Xi et al.51 noted that Arabian Sea intraseasonal SST anomalies significantly affect summer monsoon rainfall. Sreenath et al.52 further emphasized a heightened convective activity along the west coast of India. As a result, rainfall on the west coast of India is increasingly characterized by convective patterns, marking a notable shift in its meteorological dynamics52,53,54. This is in good agreement with the recent poleward shift of monsoon low-level jet (LLJ)55,56,57,58,59. Notably, this shift is associated with convective activity/cyclonic activity, which might also be a significant factor contributing to the increased rainfall in NWI in recent years. While the potential for MDs to generate precipitation is well-established, their dynamics in the Arabian Sea region have not yet been studied and understood. This research will attempt to address the causes of the rising frequency of MDs in the Arabian Sea during monsoon season, offering a contrast to the declining frequencies observed over the BoB. By investigating the mechanisms driving depression genesis, especially in the northern Arabian Sea, this study focused on the dynamics of MDs and aids in forecasting ISM rainfall under the influence of climate change.

Results

Recent trends in the monsoon rainfall and circulation

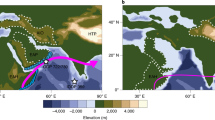

India has been experiencing a notable shift in rainfall patterns in recent decades. There has been an observed increase in rainfall over NWI and a simultaneous decrease over the parts of IGP, which is in line with a study by Kulkarni et al.5. Figure 1c illustrates the JJAS (June to September) mean rainfall trend from 1981 to 2022, clearly demonstrating a significant increasing trend in NWI and a concerning decreasing trend in IGP. The observed trend strongly aligns with the climatological variance between the periods of 1980–2000 and 2001–2020, as depicted in Fig. 1d of Mahendra et al.8 research. This correspondence is robust and corroborates findings from prior studies5,7. This shift is particularly evident during the monsoon season, traditionally characterized by the formation of mesoscale disturbances such as MDs, generally originating over the north BoB. These MDs, formed in the BoB33,60, typically traverse along the monsoon trough28,32,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, bringing substantial rainfall along their path and affecting regions in their trajectory. However, a crucial observation is that there is a significant decrease in the formation of MDs over the BoB9,35,36,40, aligning with the declining rainfall trend in the monsoon trough/IGP region. Conversely, a contrasting trend in MDs is observed over the northern Arabian Sea (Fig. 1a, b). During the period from 1981 to 2000, a total of 6 MDs were recorded, but this number nearly doubled to 11 MDs for the period 2001–2022. Most of these disturbances are shifting in a north-westward direction, with some moving towards the NWI (Fig. 1c). The genesis locations of these MDs further substantiate this surge in recent decades. Based on this analysis, it is evident that the formation of MDs during the months of JJAS is on the rise, particularly over the northern Arabian Sea. This surge in MDs formation has emerged as a one of the significant factors contributing to the increased rainfall over NWI in recent decades, this critical insight that has not been thoroughly explored until now.

a Time series (Annual) and bar (JJAS season) plots depict monsoon depressions (MDs) over the Arabian Sea. b The brown bar represents the number of MDs during 1981–2000, while the green bar represents the number of MDs during 2001–2022. c Shaded region represents rainfall (mm/decade) trends over India, MDs tracks (1981–2022) are shown within the red color box region, and genesis locations denoted by star marks (top left corner box; 1981–2000 in red, 2001–2022 in green), overlaid black dots indicating significance at a 95% confidence level. d Green vectors display 850 hPa circulation (m s−1) climatology, with red vectors (m s−1/decade) indicating trends of recent decades. e, f Regional average zonal and meridional winds (m s−1) over the Arabian Sea (55°E:67°E,6°N:16°N) and Bay of Bengal (80°E:90°E,12°N:14°N) are represented. The methodology for computing wind direction (ref. 68) is outlined (g), and the inclination angle of recent changes in low-level circulation is depicted over region (h).

Additionally, recent studies found the physical mechanisms of poleward-shift moisture through LLJ shift, explain the rise in rainfall over NWI8,15. Although previous studies have reported a poleward (northward) shift of the monsoon LLJ in recent years over the Arabian Sea56,57,59, none of the studies have quantified the extent of this shift. This finding reveals a significant change in low-level (850 hPa) circulation, as depicted in Fig. 1d. To further quantify its strength, we focus on specific regions in the Arabian Sea (55°E:67°E,6°N:16°N) and the BoB (80°E:90°E,12°N:14°N). The meridional average of zonal and meridional winds in these regions has shown a significant increase over the past two decades (Fig. 1e,f), consistent with recent trends in low-level circulation (Fig. 1d). Additionally, calculations based on ref. 68 Fig. 1g indicates a poleward shift of the monsoon LLJ by approximately 1.13 degrees northward over the (55°E:67°E,6°N:16°N) region (Fig. 1h). This significant LLJ shift appears to favorably influence dynamics by redirecting moisture supply towards NWI, thereby reducing moisture supply to the BoB and monsoon core regions20. Hence, contributing to the rainfall over that region as exhibited in Supplementary Fig. 1 (see the Supplementary information), the MDs rainfall contribution to NWI during the JJAS seasonal mean rainfall of about ~3–4% in recent decades.

Role of SST, vorticity and moisture in increasing frequency of MDs

In our investigation, we delved further into this phenomenon by examining SST, vorticity and moisture trends (Fig. 2). The SST revealed a pronounced increasing trend across the entire northern Arabian Sea basin, particularly prominent in the northwestern areas, exhibiting an increase of approximately ~0.3 °C per decade (Fig. 2a). Moreover, the averaged SST over that region exhibited a substantial and consistent increasing trend over the past four decades (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, we explored the plausible dynamic processes contributing to the formation of MDs. The essential dynamical process for the formation of MDs would be a combination of barotropic instability and the Conditional Instability of the Second Kind (CISK). Barotropic instability thrives on horizontal wind shear in jet-like currents, grabbing energy from the mean flow69. The formation of synoptic-scale weather patterns is termed “cyclogenesis,” highlighting the pivotal role of relative vorticity31 in their development; Fig. 2c, d illustrate the significantly increasing trend of spatiotemporal relative vorticity over that region. Specifically, this is in line with the recent circulation pattern change over the Arabian Sea with a poleward shift of the monsoon LLJ8,55,57,58 merging with anomalous easterlies along the monsoon trough over NWI. This convergence extends to the northern Arabian Sea region, characterized by maximum relative vorticity and likely maximum absolute vorticity trend over there (Fig. 2c). These conditions set the stage for barotropic instability, contributing to the formation of MDs. Further, Fig. 2e, f illustrate the mid-tropospheric relative humidity trend, expertly averaging between 300 to 700 hPa. The data undeniably shows a robust and consistent increase in humidity over the NWI over the past few decades. This is of paramount significance, as it directly correlates with the escalating frequency of catastrophic flooding events across the NWI, the trend is approximately 3.5% per decade, aligning seamlessly with an alarming rise in devastated floods in this region.

The upper panels show the SST trend (°C/decade) over the northern Arabian Sea (60°E 78°E–10°E 26°E) spatial (a) and temporal (red line) (b). c, d show the same as (a, b) for 850 hPa vorticity (s−1/decade). Similarly, e, f for mid-tropospheric Relative Humidity (%/decade) and g, h total column of cloud liquid water content (g/m2/decade). All variables are taken for JJAS seasonal mean and black dots and red color lines represent the trend statistically significant at a 95% confidence level.

Furthermore, this observation is reinforced by a remarkable increasing trend in the total column of cloud liquid water (CLW) over the NWI region, extending along the western coast of India. This pattern closely adheres to the findings of Sreenath et al.52. The observed increasing trend in CLW holds true when considering the entire region, signifying a significant shift in recent years (Fig. 2g, h). These findings underscore a substantial surge in convective activity over the NWI region and the western coast51 in contrast to BoB. The study predominantly focused on the northern Arabian Sea, and comparisons with the BoB revealed the contrasting results. A more comprehensive spatial analysis is provided in the Supplementary information for a broader perspective (See Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

Considering this observational evidence of SST showing to be greater >26 °C70, with significant positive vorticity at 850 hPa31, strongly motivating us to understand the underlying mechanisms at play becomes imperative. Therefore, our analysis further explores dynamical instability processes that are crucial factors for the growth of MDs. The Genesis Potential Parameter (GPP)71,72, which offers insights into the propensity for MDs formation; Dynamical instability, and Vertically Integrated Moisture Flux Transport and Convergence (VIMFT & VIMFC) spanning from 1000 to 300 hPa, could explain the moisture distribution and vertical displacement related to dynamical instability35,36.

Dynamic and thermodynamic conditions

The GPP over that region reveals a significant positive trend in recent decades (Fig. 3a, b). This trend is apparent in the parameters distribution and highlights a pronounced increase in GPP over the northern Arabian Sea region, signifying a region with enhanced potential for cyclogenesis in recent decades. This argument gains further weight when we take into account the substantial positive trend in the potential temperature difference between the 500 and 850 hPa levels over the northern Arabian Sea region, amounting to approximately 0.5 K per decade. This trend underscores the increasing dynamical instability in the atmosphere and plays a vital role in sustaining the growth of MDs (Fig. 3c, d). Which further confirmed with 500 hPa positive vertical velocity trend over that region both spatially and temporally (Fig. 3e, f). In a convectively unstable tropical atmosphere, there is a remarkable phenomenon at play. Vertical upward motion, illustrated in Fig. 3e, initially stable when considering dry adiabatic vertical motion, undergoes a shift toward instability when assessed in the context of saturated adiabatic vertical motion. This transformative process is refererred as CISK, and it precipitates dynamical instability. This condition is particularly conducive to the burgeoning development of deep convection or MDs over the northern Arabian Sea in recent years.

Like Fig. 2, a, b shows GPP, c, d potential temperature (K/decade) difference between 500 minus 850 hPa, e, f vertical velocity (m s−1/decade: positive ascent) and g, h vertically integrated moisture flux convergence (kg m−2 s−1/decade) and transport (kg m−1s−1/decade) from 1000 to 300 hPa levels. All variables taken for JJAS seasonal mean and black dots, red color lines, and red color arrows represent the trend statistically significant at a 95% confidence level.

Further, to reinforce these observations, we turn our attention to the VIMFC as well as the VIMFT, as depicted in Fig. 3g. Their trends clearly indicate a surge in moisture convergence occurring over the northern part of the Arabian Sea in recent decades. This surge aligns well with the moisture transport pattern, which extends from the NWI subcontinent to the northern reaches of the Arabian Sea, as illustrated in Fig. 3g. Furthermore when assessing the average VIMFC within that region, we discern a significant upward trajectory, as shown in Fig. 3h. These findings collectively underscore the increasing dynamical factors in recent decades, encourage to delve further into the upper-level divergence structure and vertical wind shear.

To investigate this aspect, we examine the vertical wind shear between the 200 to 850 hPa levels and the rotational winds, depicted by vectors, over the 200 hPa level (Fig. 4a). These investigations reveal a strengthening of vertical wind shear over the northern Arabian Sea region, as well as an increasing trend in the average vertical wind shear within that region (Fig. 4b). In harmony with this observation, the trend in upper-level rotational winds indicates a prominent easterly trend structure evident along the monsoon trough region via NWI, this divergent flow appears as an integral part of the upper-level anticyclone over there. Furthermore, when we scrutinize the trend in the 850 hPa meridional wind over the Arabian Sea, a clear and substantial increasing trend that extends from the southwestern Arabian Sea to the northern portion of the Arabian Sea, towards the Gujarat region is seen (Fig. 4c). Overlaying the 850 hPa wind strength reveals a robust easterly wind pattern north of the NWI, extending towards the Gulf of Oman coast (Supplementary Fig. 4a). This configuration signifies a poleward shift of the monsoon LLJ, traversing from the Arabian Sea to the NWI, with these winds converging and moving towards the Gulf of Oman coastline. The meridional wind average within that region clearly exhibits a noteworthy increasing trend (Fig. 4d). These findings collectively reinforce the idea of changing dynamics that are contributing to the growth of MDs over the northern Arabian Sea in recent years reverse is true for the BoB region, which further complimented by case study between 1984 and 2022 years (Detailed description given in the Supplementary Figs. 9–13). In addition to this, the divergence trend over 200 hPa and divergent wind trend overlaid (Fig. 4e), showing there is a positive divergence trend over 200 hPa level in the northern part of the Arabian Sea which is well consistent with the divergent flow with the low-level cyclonic circulation (Fig. 3g). The 200 hPa divergence averaged over that region is clearly display a significant positive trend in the recent decades. It is evidently emphasized that all the parameters do favor the formation of tropical disturbances such as MDs over the northern Arabian Sea with a significant positive trends in the recent decades, and these results are in agreement with conditions of Gray31.

Vertical wind shear (m s−1/Km/decade) between 200 and 850 hPa levels shaded and 200 hPa rotational winds (m s−1/decade) vectors (a), vertical wind shear over that region average (b). c, d Similar to (a) and (b) for 850 hPa meridional wind (m s−1/decade) shaded and 850 hPa wind (m s−1/decade) vectors. e, f For Upper-level divergence (s−1/decade) shaded and divergent winds (m s−1/decade) over 200 hPa vectors. Black dots, red color lines, and red color arrows represent the trend statistically significant at a 95% confidence level.

Vertical structure of dynamic composition

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the vertical structure and dynamic composition of MDs over the northern Arabian Sea. Other fundamental elements are analyzed, which include potential temperature, potential vorticity, zonal and meridional winds, and their vertical cross-section exhibited in Fig. 5. In the real atmosphere, natural forces conspire to generate both horizontal and vertical wind shears. It is crucial to note that when these wind shears surpass critical thresholds, a delicate equilibrium is disrupted, giving rise to dynamic instability, as vividly illustrated in Fig. 4a, b (Supplementary Fig. 3). The varying forces responsible for instigating critical shears possess the ability to restore stability by tempering them. This intricate interplay between forces exerts a profound influence on weather patterns across diverse spatial and temporal scales. Notably, unstable horizontal shears, typified by westerly winds in the south and easterly winds in the north, lead to what’s known as barotropic instability. Conversely, unstable vertical shears give rise to baroclinic instability, a phenomenon highlighted in Fig. 5a. The combination of these two types of instability—barotropic and baroclinic—is pivotal in the genesis of tropical disturbances.

a displays 60°E:72°E longitude averaged vertical-latitude cross-sections of JJAS mean trends in potential temperature (K/decade), indicated by shading, accompanied by zonal wind (m s−1/decade) and vertical wind contours. The zonal wind represents green solid lines Westerlies, dashed cyan lines Easterlies, and brown lines with upward vertical velocity. Similarly, b illustrates 16°N:26°N latitude-averaged vertical-longitude cross-sections of potential vorticity (PVU, 1 PVU = 10−6 K m2 kg−1 s−1/decade), shaded to denote trends, alongside meridional wind (m s−1/decade) contours represented by dashed green lines northerlies and solid black lines southerlies. Regions denoted by black dots and hatches signify statistical significance at a 95% level.

In the context of convectively unstable tropical atmospheres, the presence of significant vertical motion, as demonstrated in Fig. 5a, can act as a trigger for CISK. This intricate process affects both dry and saturated adiabatic vertical motion and plays a pivotal role in inducing dynamical instability, creating a chain reaction that influences weather patterns there. Moreover, a detailed examination of the latitude versus height potential temperature and zonal winds averaged over the region between 60°E to 78°E, reveals a consistent trend. This trend unveils a cold core in the lower troposphere and a warm core aloft, findings in harmony with prior research that has elucidated the dynamics of MDs over the BoB (Fig. 5a)28,30,31,32,33. Intriguingly, the contours of zonal wind trends reveal a distinct cyclonic flow cantered around latitudes of approximately 20°N to 22°N. Westerlies (green contours) to the south and easterlies (cyan contours) to the north characterize this pattern, as depicted in Fig. 5a. Furthermore, the pronounced positive vertical velocity trend in this specific region of the northern Arabian Sea (Fig. 5a maroon color contours), suggests the presence of deep convective disturbances33,73. Notably, one intriguing aspect is the remarkable depth of their potential vorticity structure, setting them apart from other vertical disturbances. Moving on to the longitude versus height potential vorticity and meridional winds, the trends here reveal some compelling insights. Meridional winds are aligned with the vorticity patterns within these disturbances. The absolute or relative vorticity is most prominent in the lower troposphere (Fig. 2c) but potential vorticity exhibits a peak near 700 hPa, presenting a top-heavy column that extends into the upper levels about 300 hPa. This structural characteristic, as exemplified in Fig. 5b, is a common feature among these disturbances. The meridional winds trend structure conspicuously aligns with cyclonic vorticity patterns between longitudes of 60°E to 78°E, with northerlies (green contours) and southerlies (black contours) flanking the west and east sides of the deep convection center (Fig. 5b). These observations collectively provide a robust and intricate view of the dynamics of MDs over the northern Arabian Sea. The mounting evidence unequivocally indicates a significantly escalated potential for the development of MDs in this region. This heightened susceptibility to MDs emerges as a paramount contributing factor to the substantial surge in rainfall experienced over the NWI region in recent decades (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Considering this compelling evidence, it is irrefutable that the prevalence of MDs is a conclusive driver behind the pronounced increase in rainfall observed in the NWI region over the past years.

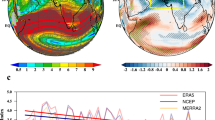

a JJAS mean 200 hPa meridional wind trends (shaded, m s−1/decade) and zonal wind trends (contours: negative denote westerlies in black dashed, positive denote easterlies in blue solid) are overlaid with green contours indicating climatological zonal wind (U200 > 20 m s−1) for 1981–2022. The magenta box marks the East Asian jet (EAJ). Black arrows show the meridional gradient of the westerly jet. b Year-to-year EAJ variation (bars) with a 17-year running standard deviation. c Similar to (b), but for the 200 hPa meridional wind (m s−1) over 0°–160°E and 20° 60°N, showing the leading mode of EOF PC1 (bars) with a 17-year running mean. d Epochal difference (2001–2022 vs 1981–2000) in the standard deviation of U200, with the same magenta box in (d) as in (a).

Mid-latitude teleconnections

SRP pattern phase shift is characterized by an anomalous barotropic anticyclone over the Caspian Sea and Korean Peninsula (see Supplementary Fig. 5), as observed in various previous studies8,13,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83, correlate with significant precipitation and surface air temperature anomalies across Europe and Asia74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83. However, the SRP pattern phase shift is intricately linked to various climatic factors, including SST anomalies in the North Atlantic and North Pacific regions. The spatial pattern of EOF1 is similar to that of the recent trend of the meridional winds over 20°N to 60°N latitudes (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 5). Additionally, recent years have seen an intensified South Asian High (SAH) and its westward and poleward shift, attributed to atmospheric heating changes over the Tibetan Plateau (TP), leading to changes in moisture distribution and vertical motion, thereby impacting precipitation patterns over South Asia known as Indian monsoon region7,8. This is an integral part of the jet streak exit region dynamics over East Asia as evidenced by strong East Asian jet decadal variability with a standard deviation of <1 m/s, a positive shift after 2000 (Fig. 6b, d).

This further inclines with the SPR pattern PC1 with 23.74% variability with the leading mode of EOF of the meridional with over 20°N:60°N and 0°:160°E (Fig. 6c). However, the western flank of this anticyclone induces the northerly flows in results due to the imbalance between the pressure gradient and Coriolis force. Further, these ageostrophic wind anomalies in turn as easterly anomalies along the monsoon trough region and trigger the anomalous cyclonic circulation over Myanmar (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, the analysis emphasizes the complex interplay between changes in the atmospheric circulation dynamics, SST anomalies over the North Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean, especially over the northern Arabian Sea, and these regional climatic features in driving monsoon variability in the recent decades. The empirical analysis of Mahendra et al.8 reveals a significant phase shift in the SRP pattern during the late 1990s, modulating with changes in SST over the northwestern Arabian Sea (NWAS) and thereby subsequent rainfall variations in the NWI. This indicates a potential combined influence of SRP by changing the monsoon circulation and LLJ poleward shift, NWAS warming by altering the ocean dynamics and thereby influencing the NWI rainfall is evidenced by regression analysis SRP index vs SST and 850 winds along with NWAS SST vs ISM rainfall (Fig. 7). We have also verified the Atmospheric General Circulation Model (AGCM) simulations to support the observational findings in this study. The ECHAM5 model, from the Atmospheric Intercomparison Project (AMIP), despite using observational boundary conditions and ERA5 SST, significantly fails to replicate key findings of recent atmospheric dynamics and rainfall changes from 2001 to 2020 versus 1981 to 200084 (Supplementary Fig. 6). It inadequately captures cross-equatorial circulation and fails to accurately represent the monsoon rainfall patterns, especially NWI and monsoon core region due to its poor depiction of large-scale features8,13. This study summarizes the multifaceted dynamics driving the increasing trend in MDs over the northern Arabian Sea, including convective instability, moisture convergence, and mid-latitude circulation changes.

Illustrate the regression of the SRP Index with SST (°C) and 850 hPa zonal (m s−1) and meridional wind (m s−1) anomalies over the Indian Ocean, alongside the Indian rainfall regression with northwestern Arabian Sea SST (°C) anomalies. black dots region and blue arrows are statistically significant at 95% level.

Discussion

India heavily depends on the summer monsoon seasonal rainfall, spanning JJAS, which produces a substantial portion, approximately 75–80%, of its annual rainfall. This crucial rainfall is greatly influenced by synoptic-scale low-pressure systems, specifically characterized as monsoon lows and MDs. It is worth noting that recent studies, including reports from the IMD, have indicated a noticeable decline in the number of MDs in BoB over the years. However, our research presents a distinctive perspective. Over the past two decades, we have observed nearly a doubling of the occurrence of MDs within the northern Arabian Sea during the JJAS season. In the realm of atmospheric dynamics, there exists a fascinating interplay of forces and conditions that have a profound impact on the formation and growth of MDs over the northern Arabian Sea.

The schematic diagram concluded (Fig. 8), that multifaceted dynamics driving the increasing trend in MDs over the northern Arabian Sea in recent years. The development of MDs is driven by convective instability within tropical atmospheres, transitioning from stable dry adiabatic to unstable saturated adiabatic vertical motion, known as CISK. This instability is crucial for MDs growth, bolstered by a significant positive trend in the potential temperature difference between the 500 and 850 hPa levels, indicating increased atmospheric dynamical instability. Convective instability, particularly evident in vertical upward motion, plays a crucial role. Additionally, trends in VIMFC and VIMFT further enhanced the moisture convergence in the northern Arabian Sea.

Genesis Potential Parameter (GPP) shows shaded areas with low-level convergence (yellow circle), anticlockwise rotating winds (northerlies west, southerlies east), a cold core below (blue), and a warm core aloft (red). Strong cloud liquid water is shaded green, maximum potential vorticity is indicated by cyan dashed circles, and upward vertical velocity is shown by a white arrow. Upper-level divergence (cyan) with clockwise rotating winds. Results align with Hunt et al.33 shown for the MDs over BoB.

This is complemented by a strong vertical wind shear and a clear divergence in upper-level winds over the region, facilitating cyclonic circulation and the formation of MDs. The poleward shift of the monsoon LLJ with an easterly along the monsoon trough via the Arabian Sea towards the Gulf of Oman enhances these conditions. A detailed examination of potential temperature, potential vorticity, and wind patterns reveals unstable horizontal and vertical shears, leading to barotropic and baroclinic instability. These instabilities are crucial for the genesis of tropical disturbances such as MDs. Notably, a cold core in the lower troposphere and a warm core aloft, along with significant positive trends in vertical velocity, indicate deep convective disturbances centered around 20°N to 22°N in the northern Arabian Sea.

Further analysis of mid-latitude circulation changes, particularly phase shift in SRP pattern, reveals its impact on the monsoon circulation. An anomalous barotropic anticyclone over the Caspian Sea and Korean Peninsula, linked to SST anomalies in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, correlates with significant precipitation and temperature anomalies over Southeast Asia. This pattern shift is associated with an intensified East Asian Jet and its westward and poleward shift, impacting moisture distribution and vertical motion, thereby affecting monsoon dynamics. The SRP pattern’s phase shift, modulated by SST changes over the NWAS, indicates a combined influence on monsoon circulation and LLJ dynamics, leading to increased MDs and subsequent rainfall variations in the northern Arabian Sea. This interplay between mid-latitude circulation changes and regional climatic features drives the observed increase in MDs, emphasizing the complex dynamics at play.

In summary, the multifaceted dynamics driving the increasing trend in MDs over the northern Arabian Sea include convective instability, moisture convergence, strengthening vertical shear, and mid-latitude circulation changes. These findings enhance our understanding of the evolving atmospheric conditions and their impact on monsoon variability and extreme rainfall, with critical implications for predicting and managing rainfall patterns in the Indian subcontinent.

Methods

Data sources and computation details

Monthly Sea Surface Temperature (SST) records from 1870 to 2022, sourced from the Hadley Center Sea Ice and SST version 1.1 (HadISST)85. For the period ranging from 1951 to 2022, we have acquired gridded rainfall data specifically pertaining to land points in India, procured from the India Meteorological Department (IMD)86. Meteorological parameters necessary for our analysis, including zonal, meridional, and vertical winds, relative humidity (RH), specific humidity, potential vorticity, and air temperature, etc., have been extracted from the European Center for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 datasets87. These datasets offer high-resolution data with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°, covering the period from 1981 to 2022. Our primary objective involves a comprehensive analysis of these variables to discern their respective trends. Furthermore, we seek to ascertain the essential dynamic and thermodynamical conditions conducive to the formation of MDs (Data source: http://www.imdchennai.gov.in/cyclone_eatlas.htm) over the Arabian Sea (60°E–78°E and 10°N–26°N). Student’s t-test is used to estimate the statistical significance of the trends and Mann_Kendall_Test is used to find the slope and p-values of the time series.

GPP computation

GPP key conditions are, 850 hPa vorticity, vertical shear, mid-tropospheric relative humidity, and mid-tropospheric instability. GPP was computed using the following formula30.

Where \({\xi }_{850}=\,\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\,-\,\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\), (s−1) 850 hPa relative vorticity, M=\(\frac{[{RH}-40]}{30}\), (%) mid-tropospheric relative humidity, \(I=({T}_{850}-{T}_{500})\) (°C) mid-tropospheric instability and S vertical wind shear between 200 and 850 hPa levels (m s−1).

Further computed vertically integrated moisture transport and convergence from 1000 to 300 hPa level.

We further computed vertically integrated moisture transport and convergence from 1000 to 300 hPa level using the above formula, where g represents the gravitational constant, u and v denote the zonal and meridional wind, respectively, and q denotes the specific humidity.

Our analysis focuses on the June to September (JJAS) months, aligning with the examination of ISM rainfall and the identification of conditions favorable for the genesis of MDs over the northern Arabian Sea.

Data availability

All data utilized in this research are openly accessible from the provided links below. 1. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk. 2 https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu. 3 https://www.imdpune.gov.in.

Code availability

The Python scripts utilized in the analysis are accessible upon reasonable request.

References

Gadgil, S. & Gadgil, S. The Indian monsoon, GDP and agriculture. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 41, 4887–4895 (2006).

Porter, J. R. et al. Food Security and Food Production Systems (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Goswami, B. N., Venugopal, V., Sengupta, D., Madhusoodanan, M. S. & Xavier, P. K. Increasing trend of extreme rain events over India in a warming environment. Science 314, 1442–1445 (2006).

Turner, A. G. & Slingo, J. M. Subseasonal extremes of precipitation and active‐break cycles of the Indian summer monsoon in a climate‐change scenario. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 135, 549–567 (2009).

Kulkarni, A. et al. Precipitation changes in India in Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region, 47–72 (Springer, 2020).

Yadav, R. K. Midlatitude Rossby wave modulation of the Indian summer monsoon. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 2260–2271 (2017).

Singh, R., Jaiswal, N. & Kishtawal, C. M. Rising surface pressure over Tibetan Plateau strengthens indian summer monsoon rainfall over northwestern India. Sci. Rep. 12, 8621 (2022).

Mahendra, N., Chilukoti, N. & Chowdary, J. S. The increased summer monsoon rainfall in northwest India: coupling with the northwestern Arabian Sea warming and modulated by the Silk Road Pattern since 2000. Atmos. Res. 297, 107094 (2024).

Mahendra, N., Nagaraju, C., Chowdary, J. S., Ashok, K. & Singh, M. A curious case of the Indian Summer Monsoon 2020: the influence of Barotropic Rossby Waves and the monsoon depressions. Atmos. Res. 281, 106476 (2023).

Yadav, R. K. & Roxy, M. K. On the relationship between north India summer monsoon rainfall and east equatorial Indian Ocean warming. Glob. Planet. Change 179, 23–32 (2019).

Sivakumar, M. V. K., Das, H. P. & Brunini, O. Impacts of present and future climate variability and change on agriculture and forestry in the arid and semi-arid tropics. Clim. Change 70, 31–72 (2005).

Konwar, M., Parekh, A. & Goswami, B. N. Dynamics of east‐west asymmetry of Indian summer monsoon rainfall trends in recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 10708 (2012).

Kosaka, Y., Nakamura, H., Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Analysis on the dynamics of a wave-like teleconnection pattern along the summertime Asian jet based on a reanalysis dataset and climate model simulations. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 87, 561–580 (2009).

Enomoto, T. Interannual variability of the Bonin high associated with the propagation of Rossby waves along the Asian jet. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 82, 1019–1034 (2004).

Yadav, R. K. The recent trends in the Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04488-7 (2024).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. Impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the relationship between the Indian monsoon rainfall and ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4499–4502 (2001).

Ashok, K., Chan, W., Motoi, T. & Yamagata, T. Decadal variability of the Indian Ocean dipole. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 1–4 (2004).

Ashok, K. & Tejavath, C. T. The Indian summer monsoon rainfall and ENSO. MAUSAM 70, 443–452 (2021).

Roxy, M. K. et al. Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian Ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient. Nat. Commun. 6, 7423 (2015).

Chowdary, J. S., Bandgar, A. B., Gnanaseelan, C. & Luo, J. Role of tropical Indian Ocean air–sea interactions in modulating Indian summer monsoon in a coupled model. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 16, 170–176 (2015).

Mahendra, N. et al. Interdecadal modulation of interannual ENSO‐Indian summer monsoon rainfall teleconnections in observations and CMIP6 models: regional patterns. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 2528–2552 (2021).

Darshana, P., Chowdary, J. S., Gnanaseelan, C., Parekh, A. & Srinivas, G. Interdecadal modulation of the Indo-western Pacific Ocean Capacitor mode and its influence on Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 54, 1761–1777 (2020).

Athira, K. S. et al. Regional and temporal variability of Indian summer monsoon rainfall in relation to El Niño southern oscillation. Sci. Rep. 13, 12643 (2023).

Keshavamurty, R. N. Power spectra of large-scale disturbances of the Indian southwest monsoon. MAUSAM 24, 117–124 (1973).

Sikka, D. R. & Gadgil, S. On the maximum cloud zone and the ITCZ over Indian, longitudes during the southwest monsoon. Mon. Weather Rev. 108, 1840–1853 (1980).

Hari, V., Villarini, G., Karmakar, S., Wilcox, L. J. & Collins, M. Northward propagation of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and strengthening of Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089823 (2020).

Godbole, R. V. The composite structure of the monsoon depression. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 29, 25 (1977).

Stano, G., Krishnamurti, T. N., Vijaya Kumar, T. S. V. & Chakraborty, A. Hydrometeor structure of a composite monsoon depression using the TRMM radar. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 54, 370 (2002).

Koteswaram, P. & George, C. A. On the formation of monsoon depressions in the Bay of Bengal. MAUSAM 9, 9–22 (1958).

Gray, W. M. Tropical Cyclone Genesis (Colorado State Univ., 1975).

Saha, K., Sanders, F. & Shukla, J. Westward propagating predecessors of monsoon depressions. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 330–343 (1981).

Hunt, K. M. R., Turner, A. G., Inness, P. M., Parker, D. E. & Levine, R. C. On the structure and dynamics of Indian monsoon depressions. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 3391–3416 (2016).

Rajendra Kumar, J. & Dash, S. K. Interdecadal variations of characteristics of monsoon disturbances and their epochal relationships with rainfall and other tropical features. Int. J. Climatol. 21, 759–771 (2001).

Prajeesh, A. G., Ashok, K. & Rao, D. V. B. Falling monsoon depression frequency: a Gray-Sikka conditions perspective. Sci. Rep. 3, 2989 (2013).

Vishnu, S., Francis, P. A., Shenoi, S. S. C. & Ramakrishna, S. S. V. S. On the decreasing trend of the number of monsoon depressions in the Bay of Bengal. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 014011 (2016).

Rajeevan, M., De, U. S. & Prasad, R. K. Decadal variation of sea surface temperatures, cloudiness and monsoon depressions in the north Indian Ocean. Curr. Sci. 79, 283–285 (2000).

Praveen, V., Sandeep, S. & Ajayamohan, R. S. On the relationship between mean monsoon precipitation and low pressure systems in climate model simulations. J. Clim. 28, 5305–5324 (2015).

Hunt, K. M. R. & Fletcher, J. K. The relationship between Indian monsoon rainfall and low-pressure systems. Clim. Dyn. 53, 1859–1871 (2019).

Chowdary, J. S. et al. Variability of summer monsoon depressions over the Bay of Bengal with special emphasis on El Niño cycle. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07245-8 (2024).

Sikka, D. R. Some aspects of the large scale fluctuations of summer monsoon rainfall over India in relation to fluctuations in the planetary and regional scale circulation parameters. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 89, 179–195 (1980).

Ding, Y., Fu, X. & Zhang, B. Study of the structure of a monsoon depression over the Bay of Bengal during Summer MONEX. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 1, 62–75 (1984).

Kumar, S. P., Roshin, R. P., Narvekar, J., Kumar, P. K. D. & Vivekanandan, E. Response of the Arabian Sea to global warming and associated regional climate shift. Mar. Environ. Res. 68, 217–222 (2009).

Deshpande, M. et al. Changing status of tropical cyclones over the north Indian Ocean. Clim. Dyn. 57, 3545–3567 (2021).

Dhavale, S., Mujumdar, M., Roxy, M. K. & Singh, V. K. Tropical cyclones over the Arabian Sea during the monsoon onset phase. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 2996–3006 (2022).

Vidya, P. J. et al. Intensification of Arabian Sea cyclone genesis potential and its association with Warm Arctic Cold Eurasia pattern. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 146 (2023).

Abhiram Nirmal, C. S. et al. Changes in the thermodynamical profiles of the subsurface ocean and atmosphere induce cyclones to congregate over the eastern Arabian Sea. Sci. Rep. 13, 15776 (2023).

Baburaj, P. P. et al. Increasing incidence of Arabian Sea cyclones during the monsoon onset phase: its impact on the robustness and advancement of Indian summer monsoon. Atmos. Res. 267, 105915 (2022).

Dasgupta, A. Arabian Sea Emerging as a Cyclone Hotspot. https://www.nature.com/articles/d44151-021-00061-7 (2021).

Evan, A. T. & Camargo, S. J. A climatology of Arabian Sea cyclonic storms. J. Clim. 24, 140–158 (2011).

Xi, J., Zhou, L., Murtugudde, R. & Jiang, L. Impacts of intraseasonal SST anomalies on precipitation during Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 28, 4561–4575 (2015).

Sreenath, A. V., Abhilash, S., Vijaykumar, P. & Mapes, B. E. West coast India’s rainfall is becoming more convective. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 36 (2022).

Ogura, Y. & Yoshizaki, M. Numerical study of OrograPhic-convective precipitation over the eastern Arabian Sea and the Ghat Mountains during the summer monsoon. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 2097–2122 (1988).

Hirose, M. & Nakamura, K. Spatial and diurnal variation of precipitation systems over Asia observed by the TRMM Precipitation Radar. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, D05106 (2005).

Sandeep, S. & Ajayamohan, R. S. Poleward shift in Indian summer monsoon low level jetstream under global warming. Clim. Dyn. 45, 337–351 (2015).

Sandeep, S., Ajayamohan, R. S., Boos, W. R., Sabin, T. P. & Praveen, V. Decline and poleward shift in Indian summer monsoon synoptic activity in a warming climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2681–2686 (2018).

Viswanadhapalli, Y. et al. Variability of monsoon low‐level jet and associated rainfall over India. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 1067–1089 (2020).

Sreepriya, S., Mirle AchutaRao, K. & Sandeep, S. Investigating the causes of poleward shift in monsoon low-level jet. In Proc. 25th EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts EGU–14372 (2023).

Varikoden, H., Revadekar, J. V., Kuttippurath, J. & Babu, C. A. Contrasting trends in southwest monsoon rainfall over the Western Ghats region of India. Clim. Dyn. 52, 4557–4566 (2019).

Koteswaram, P. & Rao, N. S. B. Formation and structure of Indian summer monsoon depressions. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 41, 62–75 (1963).

Yoon, J.-H. & Huang, W. R. Indian monsoon depression: climatology and variability. Mod. Climatol. 13, 45–72 (2012).

Krishnamurti, T. N. et al. Study of a monsoon depression (I). J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 53, 227–240 (1975).

Yoon, J.-H. & Chen, T.-C. Water vapor budget of the Indian monsoon depression. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 57, 770 (2005).

Krishnamurti, T. N. et al. Study of a monsoon depression (II). Dyn. Struct. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 54, 208–225 (1976).

Diaz, M. & Boos, W. R. Barotropic growth of monsoon depressions. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 824–844 (2019).

Lindzen, R. S., Farrell, B. & Rosenthal, A. J. Absolute barotropic instability and monsoon depressions. J. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1178–1184 (1983).

Pisharoty, P. R. & Asnani, G. A. Rainfall around monsoon depressions over India. MAUSAM 8, 15–20 (1957).

Williams, R. G. Nonlinear surface interpolations: which way is the wind blowing. In Proc. of 1999 Esri International User Conference (1999).

Holton, J. R. & Staley, D. O. An introduction to dynamic meteorology. Am. J. Phys. 41, 752–754 (1973).

Palmen, E. On the formation and structure of tropical hurricanes. Geophysica 3, 26–38 (1948).

Kotal, S. D. & Bhattacharya, S. K. Tropical cyclone Genesis Potential Parameter (GPP) and it’s application over the north Indian Sea. MAUSAM 64, 149–170 (2013).

Kotal, S. D., Kundu, P. K. & Roy Bhowmik, S. K. Analysis of cyclogenesis parameter for developing and nondeveloping low-pressure systems over the Indian Sea. Nat. Hazards 50, 389–402 (2009).

Hurley, J. V. & Boos, W. R. A global climatology of monsoon low‐pressure systems. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 1049–1064 (2015).

Ding, Q. H. & Wang, B. Circumglobal teleconnection in the Northern Hemisphere summer. J. Clim. 18, 3483–3505 (2005).

Sato, N. & Takahashi, M. Dynamical processes related to the appearance of quasi-stationary waves on the subtropical jet in the midsummer Northern Hemisphere. J. Clim. 19, 1531–1544 (2006).

Lu, R. Y., Oh, J. H. & Kim, B. J. A teleconnection pattern in upper-level meridional wind over the North African and Eurasian continent in summer. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 54A, 44–55 (2002).

Wu, R. A mid-latitude Asian circulation anomaly pattern in boreal summer and its connection with the Indian and East Asian summer monsoons. Int. J. Climatol. 22, 1879–1895 (2002).

Enomoto, T., Hoskins, B. J. & Matsuda, Y. The formation mechanism of the Bonin high in August. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 129, 157–178 (2003).

Huang, G., Liu, Y. & Huang, R. The interannual variability of summer rainfall in the arid and semiarid regions of northern China and its association with the Northern Hemisphere circumglobal teleconnection. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 28, 257–268 (2011).

Huang, R. H., Chen, J. L., Wang, L. & Lin, Z. D. Characteristics, processes, and causes of the spatio-temporal variabilities of the East Asian monsoon system. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 29, 910–942 (2012).

Chen, G., Huang, R. & Zhou, L. Baroclinic instability of the Silk Road pattern induced by thermal damping. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 2875–2893 (2013).

Saeed, S., Müller, W. A., Hagemann, S. & Jacob, D. Circumglobal wave train and the summer monsoon over northwestern India and Pakistan: the explicit role of the surface heat low. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1045–1060 (2011).

Hong, X. & Lu, R. The meridional displacement of the summer Asian jet, Silk Road pattern, and tropical SST anomalies. J. Clim. 29, 3753–3766 (2016).

Murray, D. et al. Facility for weather and climate assessments (FACTS): a community resource for assessing weather and climate variability. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E1214–E1224 (2020).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, D14 (2003).

Pai, D. S., Rajeevan, M., Sreejith, O. P., Mukhopadhyay, B. & Satbha, N. S. Development of a new high spatial resolution (0.25° × 0.25°) long period (1901–2010) daily gridded rainfall data set over India and its comparison with existing data sets over the region. MAUSAM 65, 1–18 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 Global Atmospheric Reanalysis at ECMWF as a comprehensive dataset for climate data homogenization, climate variability, trends and extremes. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 21, EGU2019-10826-1 (2019).

Acknowledgements

N.C. acknowledges the support of sponsored research grant # SRG/2021/000618 by the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. We acknowledge the director of NIT Rourkela for facilitating the work infrastructure and fellowship for M.N. We thank Prof. Shang-Ping Xie for discussions. Additionally, to the Python for its pivotal role in generating the graphical representations within this study. We also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers whose reviews helped in improving the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C. and M.N. formulated the work objective, managed the computations, and wrote the initial draft. Subsequently, J.S.C. reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chilukoti, N., Nimmakanti, M. & Chowdary, J.S. Recent two decades witness an uptick in monsoon depressions over the northern Arabian Sea. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00727-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00727-w