Abstract

We investigate 21st-century hydroclimate changes over the United States (US) during winter and the sources of projection uncertainty under three emission scenarios (SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5) using CMIP6 models. Our study reveals a robust intensification of winter precipitation across the US, except in the Southern Great Plains, where changes are very small. By the end of the 21st century, winter precipitation is projected to increase by about 2–5% K−1 over most of the US. The frequency of very wet winters is also expected to increase, with 6–7 out of 30 winters exceeding the very wet threshold under the different scenarios. Our results suggest that the enhancement of future winter precipitation is modulated largely by coupled dynamic and thermodynamic responses, though partly offset by thermodynamic responses. Overall, our results highlight a high likelihood of increasing impacts from winter precipitation due to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Changes in precipitation characteristics, especially the mean and extremes, are among the most impactful aspects of global warming because of their disproportionate damage to the environment and natural and social systems, including drought, flooding, and soil erosion1,2,3,4,5. Understanding future changes in mean precipitation and their possible cause(s) is crucial and urgent for agriculture, water resource management, and decision-making, especially at the regional-to-subregional level. Such understanding is particularly important and urgent for winter precipitation, partly because it is relatively understudied but also because it is more related to and influenced by large-scale synoptic circulations than precipitation in other seasons6.

Previous studies have shown that global mean precipitation has increased in both observations7,8 and climate model simulations9,10. However, on regional spatial and seasonal timescales there is significant variation, with increases and decreases, and the regional/seasonal magnitudes of change remain uncertain10,11. The global climate models that participated in phases 3 and 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP3 and CMIP5)10,12 broadly agree that the mean precipitation is expected to increase (decrease) under global warming in climatologically wet (dry) regions following the “wet get wetter, dry get drier” theory13,14,15. While this theory provides a fundamental understanding of how precipitation might respond to climate warming, its applicability at the regional scale may be limited due to changes in the spatial properties of moisture and regional dynamics4,5,16,17,18. Nonetheless, this potential change in global precipitation is expected partly because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor following the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship, which relates increasing water vapor to increasing air temperature7,14,19,20,21. Although global mean precipitation increases at a much smaller rate (about 1–3%/K) than water vapor (7%/K), it is constrained by changes in the net radiative cooling rate in the troposphere14,21,22,23,24. Overall, because the “wet get wetter, dry get drier” theory is applicable mostly over oceans, and a wide range of uncertainty still exists, numerous studies have tried to explain the physical mechanism behind precipitation changes for specific regions. Such understanding is vital for enhancing confidence in regional precipitation projection and refining climate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The United States (US) is one of the most extensively studied regions, partly because the impact of precipitation change can be significant due to high water resource demand25,26,27,28,29,30. The hydroclimate of the region is broadly characterized by a wet (dry) east (southwest). Notably, the precipitation exhibits substantial interannual to interdecadal variability, especially over the southwest and southern California31. Previous studies have shown that future changes in surface water availability over the US are seasonally dependent because a net gain dominates the cold half of the year (i.e., October–March), while a net loss dominates the warm half (i.e., April–September)27. Similarly, Chen et al.1 reported a projected increase (decrease) in US precipitation during the dry (wet) season under a half-degree stabilized warming experiment, leading to a weakened annual range. It is important to highlight that any seasonal shift in US precipitation patterns will further compound the water resource challenges30, a trend increasingly evident across different subregions. For example, there has been an observed increase in wintertime precipitation in California due to ongoing greenhouse gas emissions32,33, accompanied by an increase in extreme precipitation34,35. Conversely, other seasons, notably spring, are expected to become drier36, signaling an intensification of the wet-dry seasonal cycle37, more frequent dry spells and floods38, and an increase in summertime drought in California39. Furthermore, studies have also indicated a projected increase in winter precipitation over eastern North America, attributed to enhanced moisture transport by atmospheric eddies5,27,40. Additionally, a robust future increase in winter extreme precipitation is also expected over the US, while uncertainty dominates summer season projections except for consecutive dry days, which are projected to significantly increase in the northern US3. While there is a clear consensus in the literature that winter precipitation over the US will increase under future warming, information regarding the extent of these changes across individual subregions and the underlying physical mechanisms remains limited and not fully understood.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to provide regional-to-subregional projections of winter precipitation across the US. We attempt to understand the relative impacts and contributions of dynamic atmospheric processes and thermodynamic influences on future winter precipitation, using the multi-model ensemble mean response and examining the intermodel spread. The information presented here will advance our understanding of regional-to-subregional hydroclimate changes, which will be useful for managing water resources and developing regional adaptation and mitigation policies.

Results

Present-day seasonal mean precipitation and projected changes

Realistic representation of the present-day climate is the basis for developing credible projections of future changes in global warming scenario simulations2. Here, we use the various descriptive statistical measures described in Eqs. 1–4 [i.e., percentage bias, normalized root mean square error (NRMSE), pattern correlation coefficient (PCC), and Taylor skill score (TSS)], to assess the simulated seasonal precipitation accuracy relative to CRU and GPCC observations, with results presented in Figs. S1–S2 in the supplementary information. Generally, a low percentage bias and NRMSE with high PCC and TSS are desirable. All CMIP6 models used here have a high PCC ~ 0.9 and TSS ~ 0.7 across all seasons, relative to both CRU (Fig. S1) and GPCC (Fig. S2) observations. The percentage bias is lower for CRU than for GPCC, especially during the DJF and MAM seasons. The NRMSE is largely similar relative to both observations, and the values are consistent across all seasons. Overall, the CMIP6 models used here are more closely related to CRU than to GPCC. Because previous studies41 have noted that the multimodel ensemble mean (EnsMean) generally reduces the systematic biases in individual models due to cancellation of spatial errors, we further assess the performance of the CMIP6 EnsMean to accurately simulate the spatial distribution of the present-day seasonal mean precipitation by comparing the results with those of CRU and GPCC observations (Fig. S3 in the supplementary information). Relative to the two observations, EnsMean reasonably reproduces the spatial distribution of mean precipitation across the four seasons, although noticeable biases exist. For instance, EnsMean generally overestimates (underestimates) the mean precipitation over the western half (parts of SGP and SE) of the US. Also, the intense precipitation center over the central US in the summer season could not be reproduced in EnsMean, resulting in a widespread dry bias over this region. Such biases have also been reported in previous studies over the region2,42,43,44. For example, Akinsanola et al.2 similarly documented the gross exaggeration of winter precipitation by CMIP6 models over the western half of the US. These biases, which have been a long-standing problem of global climate models, have not been significantly alleviated in CMIP6 models. Despite these shortcomings, the CMIP6 EnsMean reasonably reproduces the spatial distribution of seasonal mean precipitation over the US. Thus, a discussion of precipitation using the EnsMean of CMIP6 is credible, although these biases could potentially impact future projections.

The projected changes in seasonal precipitation over the entire US and subregions (i.e., NW-Northwest, SW-Southwest, NGP-Northern Great Plains, SGP-Southern Great Plains, MW-Midwest, SE-Southeast, NE-Northeast, and US-all of US) across the SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5 scenarios are shown for EnsMean for 2070–2099 relative to the present day, 1985–2014 (Fig. 1). The projected changes presented here are scaled by area-weighted mean surface air temperature changes. Similar results are presented in Fig. S4 but without being scaled by a warming signal. In the DJF season (Fig. 1a), EnsMean projects an increase of about 1–5% K-1 in precipitation in all subregions and all of the US. Across all scenarios, the projected changes in winter precipitation are very robust, with strong intermodel agreement among the ensemble members except for SGP, where the projected changes are not only small but also exhibit large uncertainty. Specifically, all models agree on the overall sign of the change in NW, NGP, MW, SE, NE, and US, and all but one agree on SW. A wide range of uncertainty dominates the projected changes in SGP, as half of the ensemble members agree with the sign of change in EnsMean and the other half disagree. This result is consistent with a previous study based on CMIP63, where a projected robust intensification of winter precipitation characteristics was documented. Furthermore, a projected increase in precipitation of about 1–3.8% K-1 in EnsMean is also evident in most subregions and all of the US in MAM (Fig. 1b), except for SW, where a decrease is evident. We also found a slight decrease in SGP under the SSP3–7.0 and SSP5–8.5 scenarios. Also, intermodel disagreement dominates subregions where the projected decrease is evident, an indication of uncertainty in the projections. In contrast, great uncertainty dominates the projected changes in JJA and SON precipitation (Fig. 1c, d), as half of the models disagree on the sign of changes in EnsMean over all subregions and all of the US. The magnitude of the projected changes in JJA and SON precipitation is considerably smaller than that in DJF and MAM. Given that the strongest and most robust responses in the long-term projection are evident in DJF across most US subregions (Figs. 1 and S4 in the supplementary information), and recognizing the critical role of winter precipitation—which climatologically contributes up to 38% of annual totals in the NW and 33% in the SW, with significant contributions of 11% to 22% in other regions (Fig. S5)—the remainder of this paper will focus on the winter season.

Precipitation changes are shown for a December–January–February (DJF), b March–April–May (MAM), c June–July–August (JJA) and d September–October–November (SON). Bars are the EnsMean values, while the vertical line denotes the plus/minus one-time STD, which is based on the spread across models. Figures are computed as the percentage change in the regional weighted average (NW—Northwest, SW—Southwest, NGP—Northern Great Plains, SGP—Southern Great Plains, MW—Midwest, SE—Southeast, NE—Northeast, US—all of US) scaled to area-weighted mean surface air temperature changes (% K−1).

Projected changes in winter hydroclimate

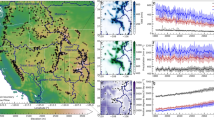

We examine the potential changes in winter hydroclimate over the US by investigating the projected changes in mean winter precipitation and changes in very wet years under SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5. The results are presented in Fig. 2 for SSP5–8.5 and Figs. S6–S7 for SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0. Under global warming and across all emission scenarios, the US will experience a robust intensification of winter precipitation at the end of the 21st century (i.e., 2070–2099). There is also strong intermodel agreement among the ensemble members, as at least 70% of the models agree on the sign of change in EnsMean at most grid points. Spatially, aside from the southern half of SW and SGP, where a decrease of about -5% K−1 is evident near the Mexico border or there is no noticeable robust change evident zonally around 35°N, most of the US will experience a future increase in winter precipitation reaching 5% K−1, with the highest over the central NGP. Over SW, the projected wetter (drier) conditions in the north (south) have also been reported in previous studies45 and have been attributed in part to the masking effect of simultaneous increases in the frequency of extreme wet and dry events38,46. Previous studies have shown that changes in locally available water vapor, along with changes in circulation due to the expansion of the Hadley cell, favor the northern SGP and SW. This also causes the region between the northern and southern edges of the tropics and midlatitudes (around 35°N) to become drier or experience no robust changes. There has also been evidence of northward movement of the mean storm track away from the subtropics, decreasing the frequency of precipitation-producing systems11.

Spatial change in winter precipitation over the US scaled with mean temperature change (% K−1; center figure). Hatching indicates grid points where at least 70% of the models agree on the sign of the EnsMean change. Time evolution of the number of wet winter years over different regions under SSP5–8.5 (time series plots). The number of wet years in the preceding 30 years is plotted and smoothed using 10-year running means. Red (blue) lines represent the multimodel ensemble median (EnsMean). Orange lines represent individual model results. The horizontal dotted gray line marks the reference of 1.5 out of 30 winter wet years based on the 95th percentile value in the historical period (1985–2014).

We further examined the number of winters surpassing the 95% threshold relative to the historical period of 1985–2014, and we found a consistent increase in the number of very wet winters over the entire US, as indicated by EnsMean and the multimodel ensemble median. In fact, by the end of the 21st century, approximately 6 (7) out of 30 winters under SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0 (SSP5–8.5) are expected to exceed the very wet threshold, representing more than a fourfold increase compared to the 1.5 out of 30 in the historical period. The sharpest upward trend is observed in MW and NE, with more than 6 (9) out of 30 winters exceeding the very wet winter threshold under SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0 (SSP5–8.5). In these subregions, at least one out of every five winters in the future is projected to be wetter. Furthermore, NGP and NW also exhibit similar and consistent increases in very wet winters, with the number of such winters by the end of the century being comparable to that in the entire US. SE exhibits a slower increase in the number of very wet winters toward the end of the century, especially under SSP2–4.5, with the multimodel ensemble median plateauing around 2060. Under SSP3–7.0, there is a slight decrease after 2050, followed by a gradual increase after 2070. Similarly, the SSP5–8.5 scenario shows a small dip after 2065 but steadily increases afterward. SW also experiences an increase in wetter winters, although this increase is lower when compared to other subregions and the entire US. In contrast, both EnsMean and the median suggest little or no change in the number of very wet winters in SGP, although some model members suggest a slight increase. Overall, all regions except SGP will experience a significant increase in the number of very wet winters, which is more pronounced at the end of the 21st century. This result is consistent with the projected rightward shift in the winter precipitation histogram across most subregions of the US, and across individual models (Figs. S8–S10).

Lastly, we quantify how the contributions of fractional uncertainty vary as a function of projection lead time, we examine the fraction of the total variance in mean winter precipitation projections due to each source of uncertainty (i.e., model uncertainty, internal variability, and scenario uncertainty) for different lead times in the 21st century (see Text S1 in the supplementary information for technical details). Across all of the US and its subregions, model uncertainty (blue) is the dominant contributor at all lead times (Fig. 3). Before the 2070s, both internal variability (orange) and model uncertainty (blue) are significant factors, but the importance of internal variability declines rapidly with increasing lead times. The contribution of scenario uncertainty is very small before the 2050s and only becomes important at the end of the 21st century. It is important to note that the contribution of scenario uncertainty is negligible over the SGP and largest over the NGP, MW, and NE regions.

The fraction of total variance in mean winter precipitation projections explained by the three components of total uncertainty (unit: %) is shown for a NW—Northwest, b SW—Southwest, c NGP—Northern Great Plains, d SGP—Southern Great Plains, e MW—Midwest, f SE—Southeast, g NE—Northeast, and h US—all of the US. Blue, green, and orange shading represent model uncertainty, scenario uncertainty, and internal uncertainty, respectively.

Dynamic and thermodynamic contributions to winter precipitation changes and uncertainty

Considering that the strongest and most robust response in the long-term projection is found in SSP5–8.5, we also focus here on the SSP5–8.5 scenario to reveal the physical processes responsible for the projected changes and associated uncertainty in winter precipitation over the entire US and its subregions. We diagnose the moisture budget equations (MBEs) described in Eqs. 5–9, and the results of the projected changes in all terms of the MBEs are presented in Fig. 4 for the entire US and its subregions. Our results show that the projected increase in winter precipitation over the entire US is dominated by the contribution from the nonlinear term (NL), with a pronounced residual term, while the effects of the vertical thermodynamic term \((-\langle \bar{\omega }{\partial }_{p}{q}^{{\prime} }\rangle ,{vertical\; TH})\) and horizontal thermodynamic term \((-\langle {\overline{\overrightarrow{{u}_{h}}}}\cdot \nabla {q}^{{\prime} }\rangle ,{horizontal\; TH})\) partly offset the increase in precipitation. The projected changes over the subregions are similar to that of the entire US and dominated by an increase in NL and residual terms under global warming, except for SW and SGP, where the effect of the residual term is opposite in sign. It is worth noting that SW and NGP exhibit the largest offset due to vertical TH, and only NGP and SGP have a pronounced offset due to the horizontal dynamic term \((-\langle {\vec{{u}_{h}}}^{{\prime} }\cdot \nabla \bar{q}\rangle ,{horizontal}\; {\rm{DY}})\). Distinctively, the projected increase in NW precipitation is dominated by the contribution from vertical TH, NL, and residual terms. Overall, the pronounced contribution from NL and residual terms further emphasizes the important role of transient eddies in winter precipitation changes. It is important to note that the dominant role of transient eddies in winter precipitation changes over the US is largely consistent across emission scenarios, as similar results are also evident based on SSP2–4.5 (see Fig. S11). The increasing precipitation is balanced by evaporation, which is also positive and robust across the entire US and its subregions.

The changes in moisture budget terms in the long term (2070–2099, under the SSP5–8.5 scenario) averaged over all of the US and seven subregions relative to 1985–2014. The bars represent EnsMean, while the vertical line denotes the plus/minus one-time STD, which is based on the spread across models. All terms are scaled by the area-mean warming over the subregions. Unit: %/K.

We further assess whether the results of the subregional changes in the MBE terms presented herein are consistent with the spatial changes. We found that most regions of the US exhibit spatially uniform changes in the MBE terms within the subregions, and the results are largely consistent with the subregional weighted average, except for SW and SGP (Fig. S12). We previously noted that the northern (southern) SW and SGP exhibit a projected wetter (drier) condition. While the sign of change of the projected NL is spatially consistent across these subregions, the horizontal TH, horizontal DY, and residual terms have opposite signs, especially within SW, such that some parts of the subregion are positive/negative in the south while exhibiting a reversal to the north. These findings further highlight the need to also assess spatial changes while conducting subregional analysis, as some signals may be impacted by averaging. Nevertheless, our results show that the drier winter conditions evident over the southern SGP and SW may be due to changes in the horizontal DY and residual terms (Fig. S12).

In general, the changes in regional winter precipitation over the US can be partitioned into (a) regions where moisture increases (evaporation and/or \({q}^{{\prime} }\)) or the interaction between q' and \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) dominate, and (b) regions where increases in transient eddies and/or \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) dominate. NW, SGP, MW, and SE (US, SW, NGP, and NE) fall into the former (latter) category. Specifically, consistent with the results presented in Fig. 4, for regions under the (a) category, except for MW, the residual terms are much lower than the precipitation increase and dominant terms. Over NW, although NL contributes to the precipitation increase, moisture increase \(({q}^{{\prime} })\) is the main source of NL. Over SGP and SE, NL is due to the interaction between \({q}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\). For regions under (b), the changes in vertical velocity anomalies \(({\omega }^{{\prime} })\) are negative (i.e., upward motion) over US, SW, NGP, and NE, which is consistent with the precipitation changes in these regions (see Fig. 4 and \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) in Fig. S13). These changes are positive (i.e., downward motion) over NW, SGP, MW, and SE, which is inconsistent with the projected winter precipitation increases. As previously highlighted, this is due to the significant contributions from moisture increases. While the results from the moisture budget diagnosis earlier discussed largely explain changes in region (a), we further diagnose the quasi-geostrophic (QG) omega equation following Eq. 10 to quantitatively explain the possible reasons for the enhancement of \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\). Contrary to previous studies that have considered only the nondivergence level (i.e., 500 hPa), we consider the mid- to lower troposphere because the largest changes in \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) occur at this level across all regions under consideration (see Fig. S14). We note that large enhancement of \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) is also evident in the upper troposphere in NE, but compared to the present-day climatology, the relative changes are much larger in the mid- to lower troposphere. In Fig. S13, the projected changes in QG omega \(({{\omega }^{{\prime} }}_{{QG}})\) closely resemble the EnsMean changes \(({\omega }^{{\prime} })\), albeit with slight differences, which may be due to numerical errors and the neglect of non-QG processes. Our results show that diabatic heating plays a primary role in driving the increasing \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) over US, SW, NGP, and NE.

As shown previously, a noticeable spread among the CMIP6 models is seen in the projection of winter precipitation. To understand the potential source of this projection uncertainty, we show the relationship between precipitation and the dominant moisture budget terms in each model (Figs. 5 and S15–S18 in the supplementary information). While NL dominates the EnsMean projected changes in winter precipitation across the entire US and its subregions, as evident in Fig. 4, the relationship between NL and precipitation is positive and statistically significant across the models over the entire US, SW, NGP, SE, and NE (Fig. 5). In contrast, the relationship between precipitation and vertical TH, horizontal DY, and horizontal TH is not statistically significant in most subregions (Figs. S15, S16, and S17, respectively). However, vertical TH (horizontal DY) is positively and significantly related to precipitation over NW and SGP (NW and NGP), while horizontal TH is negatively and significantly related to precipitation over NGP, SGP, and MW.

The relationship between winter precipitation changes and NL is shown for a US—all of the US, b NW—Northwest, c SW—Southwest, d NGP—Northern Great Plains, e SGP—Southern Great Plains, f MW—Midwest, g SE—Southeast, and h NE—Northeast, under the SSP5–8.5 scenario. The solid lines indicate a linear fit, with the correlation coefficient and p value shown at the top. Unit: %/K.

In contrast, the vertical dynamic term \((-\langle {\omega }^{{\prime} }{\partial }_{p}\bar{q}\rangle ,{vertical}\; {\rm{DY}})\) and precipitation are positively and significantly correlated over all of the US and its subregions except NGP (Fig. S18), suggesting that the models with stronger vertical circulation weakening will yield a smaller increase in precipitation. Based on the overall contribution from the NL term and the statistically significant relationship between changes in precipitation and vertical DY, we further explore the separate contributions of the changes in vertical velocity \(({\omega }^{{\prime} }\)) and changes in humidity (q’) and present the results in Table S2. We found that precipitation changes are statistically significantly correlated with \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) over NW, SW, NGP, SGP, and SE. In contrast, except for NE, we found no statistically significant relationship between winter precipitation change and q’ across the entire US and its subregions.

We further explore whether the uncertainty in winter precipitation projection and moisture budget terms is related to the spread in global mean surface air temperature (GMSAT) changes (Figs. S19–S22). Our result shows that the uncertainty in the winter precipitation projection and moisture budget terms is not significantly related to the spread of GMSAT changes except for vertical TH, which is negatively significantly related to GMSAT over SW (Fig. S21c). This suggests that models projecting a warmer GMSAT under SSP5–8.5 over SW will project a larger decrease in vertical TH. This is a unique feature of the winter precipitation changes over the US, and different from other land regions of the world such as the high mountains of Asia47. We, therefore, conclude that the projection uncertainty in winter precipitation over the US may not be dominated by the spread of GMSAT. Instead, it is closely associated with vertical DY (Fig. S18), implying that the uncertainty of circulation changes will shape the projection uncertainty of US winter precipitation1,48,49,50.

Discussion

In this study, we investigate future changes in precipitation over the entire US and its subregions and further assess the dynamic and thermodynamic contributions to these precipitation changes alongside potential sources of projection uncertainty using CMIP6 models. Our results show a future intensification of winter precipitation over the entire US and its subregions, except for SGP, where the projected changes are small and highly uncertain. We note that the projected changes in winter precipitation are in contrast to other seasons, especially JJA and SON, where a wide range of uncertainty dominates the projected results, as most individual models do not agree on the sign of the EnsMean change. The relative contributions of the thermodynamic response associated with water vapor changes, and the dynamic responses associated with atmospheric circulation changes under global warming are identified. Our main findings are summarized as follows:

-

1.

The future winter precipitation at the end of the 21st century (2070–2099) will increase by 1.9–4.5% K−1 over the US subregions and by ~2.4% K−1 over the entire US except for SGP, where the increase is very small (~0.2–1.2% K−1) under SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5, as estimated from EnsMean. Spatially, we found subregional variation in the projected winter precipitation over the northern (southern) SW and SGP, such that projected wetter (drier) conditions are evident. Specifically, a decrease of about −5% K−1 is evident near the Mexico border, no noticeable robust change is evident zonally around 35°N, and a projected increase of about 3% K−1 is expected over the northern half of the subregions. The overall projected increase is more robust and pronounced (i.e., increases are statistically significant and consistent across most CMIP6 models) under SSP5–8.5.

-

2.

All of the US and its subregions, except for SGP, will experience a significant increase in the number of very wet winters in the future. Specifically, under global warming, approximately 6 (7) out of 30 winters under SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0 (SSP5–8.5) are expected to exceed the very wet threshold.

-

3.

Across the US and its subregions, model uncertainty is the dominant source of uncertainty throughout the 21st century, accounting for more than 55% of the total variance. The contribution of internal variability is mostly important before 2070, while scenario uncertainty becomes increasingly important toward the end of the 21st century, especially in the NGP, MW, and NE.

-

4.

Across most subregions of the US, the enhancement of future winter precipitation is dominated by the contribution from the non-linear and residual terms, and partly offset by thermodynamic responses, which measure the contribution from water vapor changes associated with global warming, although there is evidence of dynamic responses, which measure the contribution from atmospheric circulation changes. The pronounced contribution from the NL and residual terms further emphasizes the important role of transient eddies in US winter precipitation changes.

-

5.

In general, the subregional changes in winter precipitation over the US can be partitioned into (a) regions where moisture increases (evaporation and/or q') or the interaction between q' and ω' dominate, and (b) regions where increases in transient eddies and/or \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) dominate. NW, SGP, MW, and SE (US, SW, NGP, and NE) fall into the former (latter) category. While the result from moisture budget diagnosis largely explains the reasons for changes in region (a), diabatic heating plays a primary role in driving the increasing \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) over region (b), based on the diagnosis of the quasi-geostrophic (QG) omega equation.

-

6.

The projection uncertainty of late 21st-century winter precipitation over the US is closely associated with the uncertainty of atmospheric circulation changes, although in some instances other terms also contribute to the uncertainty in a specific subregion.

The robust projected intensification of winter precipitation over the entire US and its subregions, including the climatologically dry region, provides significant opportunities for policy interventions and adaptation decisions.

Methods

In this study, 19 CMIP6 models, described in Table S1 (see Eyring et al.51 for details of the experiment), are used to examine future changes in seasonal hydroclimate and associated mechanisms over the US. Unless otherwise stated, we analyze monthly precipitation, evaporation, near-surface air temperature, sea level pressure, specific humidity, wind fields, and vertical velocity datasets available at the time of analysis. We use the historical simulations and projections under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), which include the SSP2–4.5 (low), SSP3–7.0 (medium), and SSP5–8.5 (high) emission scenarios52,53, and we use only the first realization (r1i1p1f1) from each model. To investigate the response of the hydro-climatic variables (e.g., precipitation, evaporation, and other moisture budget terms) to global warming, we compare the present-day period (1985–2014) in the historical simulations with the late 21st-century projections (2070–2099). We focus on the end of the century, when forced changes are relatively larger compared to internal variability. Furthermore, the multimodel ensemble mean (referred to hereafter as “EnsMean”) is employed in this study to address systematic biases due to model differences54. All datasets are regridded to the lowest model horizontal resolution (2.81° × 2.81°) using an area-conserving remapping procedure, which is implemented in the Climate Data Operators (https://code.zmaw.de/projects/cdo) to produce EnsMean. Following Akinsanola et al.3, we estimate statistical robustness, particularly for analyses of spatial changes, by highlighting grid points where at least 70% of the CMIP6 models agree on the sign of change in EnsMean. We focus mainly on the land area of the United States. The future changes in precipitation across the four seasons (December–January–February, DJF; March–April–May, MAM; June–July–August, JJA; and September–October–November, SON) under the SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5 scenarios are first assessed before focusing subsequent analysis on the DJF season, where projected changes are the most robust. To investigate extreme winter conditions, we define a very wet winter year if the precipitation exceeds the 95th percentile precipitation threshold during the historical period. To evaluate the CMIP6 present-day simulations, the EnsMean seasonal precipitation is compared with two gridded observations, namely the Climate Research Unit TS V4.07 at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° (CRU)55, and the Full Data Product from the Global Precipitation Climatology Center with a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° (GPCC V7)56.

Broad spatial assessment and several summary statistics are used to evaluate the models, including percentage bias, normalized root mean square error (NRMSE), pattern correlation coefficient (PCC), and Taylor skill score (TSS), all expressed in Eqs. 1–4.

where M and O represent the model and observation means; Cov and Var denote covariance and variance, respectively; n is the number of observations; σ is the standard deviation, and PCC0 is the maximum attainable PCC set to 1. The TSS has values ranging from 0 to 1, corresponding to no match or a perfect match between the model and observations. Several studies have used TSS to assess model performance57,58.

Previous studies have noted that the source of uncertainty in 21st-century precipitation projections can be separated into three components: internal variability, model uncertainty, and scenario uncertainty59,60,61,62. We employ the method developed by refs. 62,63 to separate and quantify the uncertainty in U.S. winter precipitation projections arising from these three components (see Text S1 in the supplementary information for technical details). The method requires that all the models have exactly the same ensemble members.

To understand the mechanisms of change and uncertainty in US precipitation under warming, moisture budget analysis is used1,15. From a moisture budget perspective, precipitation variability and changes are generally influenced by changes in both moisture and atmospheric circulation. The vertically integrated anomalous moisture equation is presented in Eq. 5,

where P is precipitation, E is evaporation, q is specific humidity, and \(\vec{{u}_{h}}\) and \(\omega\) denote horizontal wind and vertical pressure velocity, respectively; the primes denote the changes relative to the baseline climatology, and angle brackets \((\)“\(\langle \rangle\)”\()\) indicate the mass integral through the entire troposphere, as shown in Eq. 6:

On the seasonal mean timescale, the time derivative of specific humidity, \({\partial }_{t}{\langle {\rm{q}}\rangle }^{{\prime} }\), can be ignored since it is much smaller than the other terms; \(-{\langle \overrightarrow{{u}_{h}}\cdot {\nabla }_{h}q\rangle }^{{\prime} }\) represents horizontal moisture advection, and \(-{\langle \omega {\partial }_{p}q\rangle }^{{\prime} }\) represents vertical moisture advection, which can be further divided as follows:

where (–) denotes the baseline climatology. The thermodynamic terms in the vertical and horizontal moisture advection are \(-\langle \bar{\omega}{\partial }_{p}{q}^{{\prime} }\rangle\) and \(-\langle {\overline{\overrightarrow{{u}_{h}}}}\cdot \nabla {q}^{{\prime} }\rangle\), respectively, while the dynamic terms are \(-\langle {\omega }^{{\prime} }{\partial }_{p}\bar{q}\rangle\) and \(-\langle {\overrightarrow{{u}_{h}}}^{{\prime} }\cdot \nabla \bar{q}\rangle\), respectively. \(-\langle {\overrightarrow{{u}_{h}}}^{{\prime} }\cdot \nabla {q}^{{\prime} }\rangle\) and \(-\left\langle {\omega }^{{\prime} }{\partial }_{p}{q}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle\) are the horizontal and vertical non-linear terms, respectively, and their sum is denoted as NL. Therefore, the overall changes in precipitation can be expressed as:

Please note that the residual term includes transient eddies on intra-seasonal or sub-monthly timescales64,65 and contributions from surface processes due to topography66.

Finally, we use the quasi-geostrophic (QG) omega50,67,68 equation to diagnose vertical omega anomalies \(({\omega }^{{\prime} }\)). Specifically, \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) is decomposed into contributions from diabatic heating \(({{\omega }^{{\prime} }}_{Q})\), vertical difference of vorticity advection \(({{\omega }^{{\prime} }}_{{vort}})\), and horizontal temperature advection \(({{\omega }^{{\prime} }}_{{therm}})\):

where the overbar and prime indicate DJF present-day mean quantities and projected changes for the period of 2070–2099. \(\sigma =-\frac{{RT}}{P}{\partial }_{p}\mathrm{ln}\theta\) denotes static stability, f is the Coriolis parameter, P is atmospheric pressure, cp is specific heat at constant pressure, \({\vec{u}}_{g}\) is geostrophic wind velocity, T is air temperature, ξ is relative vorticity, and Q is diabatic heating, which is calculated as the residual term in the temperature budget equation50,69. The QG analysis presented here is based on daily outputs of four CMIP6 models (BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, EC-Earth3, and INM-CM5-0), with projection results for SSP5–8.5.

Data availability

All datasets used in this study are publicly and freely available. CMIP6 data are publicly available through the Earth System Grid Federation at http://esgf.llnl.gov/. The Global Precipitation Climatology Center (GPCC) observation dataset is provided by Deutscher Wetterdienst and can be accessed at https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/GPCC/html/download_gate.html. Similarly, the Climate Research Unit (CRU) observation dataset is provided by the University of East Anglia and can be accessed at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/. The derived data generated for the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All analyses and figures were computed and drawn using NCAR Command Language (https://www.ncl.ucar.edu/) and Python (https://www.python.org/). The code used for the analysis in this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Chen, Z. et al. Global land monsoon precipitation changes in CMIP6 projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086902 (2020).

Akinsanola, A. A., Kooperman, G. J., Pendergrass, A. G., Hannah, W. M. & Reed, K. A. Seasonal representation of extreme precipitation indices over the United States in CMIP6 present-day simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094003 (2020).

Akinsanola, A. A., Kooperman, G. J., Reed, K. A., Pendergrass, A. G. & Hannah, W. M. Projected changes in seasonal precipitation extremes over the United States in CMIP6 simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104078 (2020).

Liang, W. & Zhang, M. Increasing future precipitation in the southwestern US in the summer and its contrasting mechanism with decreasing precipitation in the spring. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 (2022).

Liang, W. & Zhang, M. Transient precipitation increase during winter in the Eastern North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 (2022).

Ning, L., Mann, M. E., Crane, R. & Wagener, T. Probabilistic projections of climate change for the mid-Atlantic region of the United States: Validation of precipitation downscaling during the historical era. J. Clim. 25, 509–526 (2012).

Wentz, F. J., Ricciardulli, L., Hilburn, K. & Mears, C. How much more rain will global warming bring? Science 317, 233–235 (2007).

Gu, G., Adler, R. F., Huffman, G. J. & Curtis, S. Tropical rainfall variability on interannual-to-interdecadal and longer time scales derived from the GPCP monthly product. J. Clim. 20, 4033–4046 (2007).

Vecchi, G. A. & Soden, B. J. Global warming and the weakening of the tropical circulation. J. Clim. 20, 4316–4340 (2007).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Global Climate Projections. in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Collins, M. et al. Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility. in Climate Change 2013 - The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 1029–1136 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Chou, C. & Neelin, J. D. Mechanisms of global warming impacts on regional tropical precipitation. J. Clim. 17, 2688–2701 (2004).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Chou, C., Neelin, J. D., Chen, C.-A. & Tu, J.-Y. Evaluating the “rich-get-richer” mechanism in tropical precipitation change under global warming. J. Clim. 22, 1982–2005 (2009).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. The response of precipitation minus evapotranspiration to climate warming: Why the “wet-get-wetter, dry-get-drier” scaling does not hold over land. J. Clim. 28, 8078–8092 (2015).

Chadwick, R. & Good, P. Understanding nonlinear tropical precipitation responses to CO2 forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4911–4915 (2013).

Greve, P. et al. Global assessment of trends in wetting and drying over land. Nat. Geosci. 7, 716–721 (2014).

Manabe, S. & Wetherald, R. T. The effects of doubling the CO2 concentration on the climate of a general circulation model. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 3–15 (1975).

Trenberth, K. E. Changes in precipitation with climate change. Clim. Res. 47, 123–138 (2011).

Akinsanola, A. A., Zhou, W., Zhou, T. & Keenlyside, N. Amplification of synoptic to annual variability of West African summer monsoon rainfall under global warming. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3 (2020).

O’Gorman, P. A., Allan, R. P., Byrne, M. P. & Previdi, M. Energetic constraints on precipitation under climate change. Surv. Geophys. 33, 585–608 (2012).

Endo, H. & Kitoh, A. Thermodynamic and dynamic effects on regional monsoon rainfall changes in a warmer climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1704–1711 (2014).

Pendergrass, A. G. & Hartmann, D. L. The atmospheric energy constraint on global-mean precipitation change. J. Clim. 27, 757–768 (2014).

Cook, B. I., Ault, T. R. & Smerdon, J. E. Unprecedented 21st century drought risk in the American Southwest and Central Plains. Sci. Adv. 1 (2015).

Seager, R. & Vecchi, G. A. Greenhouse warming and the 21st century hydroclimate of southwestern North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21277–21282 (2010).

Seager, R. et al. Dynamical and thermodynamical causes of large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle over North America in response to global warming. J. Clim. 27, 7921–7948 (2014).

Seager, R. et al. Causes of the 2011–14 California drought. J. Clim. 28, 6997–7024 (2015).

Song, F., Leung, L. R., Lu, J. & Dong, L. Future changes in seasonality of the North Pacific and North Atlantic subtropical highs. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45 (2018).

Ting, M., Seager, R., Li, C., Liu, H. & Henderson, N. Mechanism of future spring drying in the southwestern United States in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 31, 4265–4279 (2018).

Dettinger, M. D., Cayan, D. R., Diaz, H. F. & Meko, D. M. North-South precipitation patterns in western North America on interannual-to-decadal timescales. J. Clim. 11, 3095–3111 (1998).

Allen, R. J. & Luptowitz, R. El Niño-like teleconnection increases California precipitation in response to warming. Nat. Commun. 8 (2017).

Neelin, J. D., Langenbrunner, B., Meyerson, J. E., Hall, A. & Berg, N. California winter precipitation change under global warming in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 ensemble. J. Clim. 26, 6238–6256 (2013).

Polade, S. D., Gershunov, A., Cayan, D. R., Dettinger, M. D. & Pierce, D. W. Precipitation in a warming world: Assessing projected hydro-climate changes in California and other Mediterranean climate regions. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017).

Zecca, K., Allen, R. J. & Anderson, R. G. Importance of the El Niño teleconnection to the 21st century California wintertime extreme precipitation increase. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45 (2018).

Gao, Y. et al. Robust spring drying in the southwestern U.S. and seasonal migration of wet/dry patterns in a warmer climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1745–1751 (2014).

Allen, R. J. & Anderson, R. G. 21st century California drought risk linked to model fidelity of the El Niño teleconnection. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1 (2018).

Swain, D. L., Langenbrunner, B., Neelin, J. D. & Hall, A. Increasing precipitation volatility in twenty-first-century California. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 427–433 (2018).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L. & Touma, D. Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3931–3936 (2015).

Strong, C., McCabe, G. J. & Weech, A. Step increase in eastern U.S. precipitation linked to Indian Ocean warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47 (2020).

Akinsanola, A. A. & Zhou, W. Ensemble-based CMIP5 simulations of West African summer monsoon rainfall: current climate and future changes. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 136, 1021–1031 (2019).

Sheffield, J. et al. North American climate in CMIP5 experiments. Part I: evaluation of historical simulations of continental and regional climatology. J. Clim. 26, 9209–9245 (2013).

Seager, R. et al. Whither the 100th meridian? The once and future physical and human geography of America’s arid–humid divide. Part II: The meridian moves east. Earth Interact. 22, 1–24 (2018).

Lin, Y. et al. Causes of model dry and warm bias over central U.S. and impact on climate projections. Nat. Commun. 8 (2017).

O’Gorman, P. A. Contrasting responses of mean and extreme snowfall to climate change. Nature 512, 416–418 (2014).

Yoon, J.-H. et al. Increasing water cycle extremes in California and in relation to ENSO cycle under global warming. Nat. Commun. 6, 8657 (2015).

Qiu, H., Zhou, T., Chen, X., Wu, B. & Jiang, J. Understanding the diversity of CMIP6 models in the projection of precipitation over Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106553 (2024).

Chen, X. & Zhou, T. Distinct effects of global mean warming and regional sea surface warming pattern on projected uncertainty in the South Asian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9433–9439 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Observationally constrained projection of Afro-Asian monsoon precipitation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2552 (2022).

Nie, J., Dai, P. & Sobel, A. H. Dry and moist dynamics shape regional patterns of extreme precipitation sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8757–8763 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Akinsanola, A. A. & Zhou, W. Projection of West African summer monsoon rainfall in dynamically downscaled CMIP5 models. Clim. Dyn. 53, 81–95 (2019).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7 (2020).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC’s new land surface precipitation climatology based on quality-controlled in situ data and its role in quantifying the global water cycle. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 115, 15–40 (2014).

Faye, A. & Akinsanola, A. A. Evaluation of extreme precipitation indices over West Africa in CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 58, 925–939 (2022).

Li, Z., Liu, T., Huang, Y., Peng, J. & Ling, Y. Evaluation of the CMIP6 Precipitation Simulations Over Global Land. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002500 (2022).

Cox, P. & Stephenson, D. A changing climate for prediction. Science 317, 207–208 (2007).

Deser, C., Knutti, R., Solomon, S. & Phillips, A. S. Communication of the role of natural variability in future North American climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 775–779 (2012).

Tebaldi, C. & Knutti, R. The use of the multi-model ensemble in probabilistic climate projections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 365, 2053–2075 (2007).

Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. The potential to narrow uncertainty in regional climate predictions. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 90, 1095–1108 (2009).

Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. The potential to narrow uncertainty in projections of regional precipitation change. Clim. Dyn. 37, 407–418 (2011).

Trenberth, K. E. & Guillemot, C. J. Evaluation of the global atmospheric moisture budget as seen from analyses. J. Clim. 8, 2255–2272 (1995).

Zhou, T.-J. & Yu, R.-C. Atmospheric water vapor transport associated with typical anomalous summer rainfall patterns in China. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (2005).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

Hu, K., Xie, S.-P. & Huang, G. Orographically anchored El Niño effect on summer rainfall in central China. J. Clim. 30, 10037–10045 (2017).

Kosaka, Y. & Nakamura, H. Mechanisms of meridional teleconnection observed between a summer monsoon system and a subtropical anticyclone. Part I: The Pacific–Japan Pattern. J. Clim. 23, 5085–5108 (2010).

Nie, J., Shaevitz, D. A. & Sobel, A. H. Forcings and feedbacks on convection in the 2010 Pakistan flood: Modeling extreme precipitation with interactive large‐scale ascent. J. Adv. Model. Earth. Syst. 8, 1055–1072 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the World Climate Research Program’s (WCRP) working group on coupled modeling, which is responsible for the CMIP6 models. The authors acknowledge the climate modeling groups listed in Table S1 for producing and making their model outputs available, and the ESGF for archiving the model outputs and providing access. We are also grateful to the services that have operated the CRU and GPCC datasets. This study is supported by the Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Biological and Environmental Research as part of the Regional and Global Model Analysis program area. The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) is operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract DE-AC05-76RLO1830.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript concept was designed by A.A.A. Data analysis was performed by A.A.A., C.Z., and B.V., while A.A.A. wrote the manuscript and edited it alongside C.Z., K.G.J., and B.V. All authors discussed the study results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinsanola, A.A., Chen, Z., Kooperman, G.J. et al. Robust future intensification of winter precipitation over the United States. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 212 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00761-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00761-8

This article is cited by

-

Impacts of 1.5°C and 2.0°C Global Warming on the Onset, Cessation, and Length of the Rainy Season in Global Land Monsoon Regions

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2026)

-

Understanding drivers and uncertainty in projected African precipitation

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Projected changes in African easterly wave activity due to climate change

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Anthropogenic warming is accelerating recent heatwaves in Africa

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)